Nov 2017

The Farm

November 01 2017 02:33 PM Filed in: Children 1950s

About 1950, our mother’s aunt, Beat, and her husband Bill sold up their grocery store and their Balwyn house, took their youngest son out of school, and bought a dairy farm in the Dandenong Ranges at Nangana, near Cockatoo.

It was called “Sefton Park”, but it became “The Farm” to us, as we were growing up, and it was one of the very, very few places we visited socially.

By the time we were regularly visiting The Farm, the eldest son, Doug had married and moved out. He became a bus driver and spent his whole life living at Avonsleigh, near Emerald.

The next son, Rob, had married young, built another house on the property and had a child, Julie. Rob’s wife, Pat, died of breast cancer when Julie was still a baby, and Rob moved back to his family home. About that time our mother’s unmarried aunt, Bert, moved to The Farm, presumably to help her sister with this motherless baby.

So this rural property supported Beat and Bill, Rob and his daughter Julie, youngest son John, and Beat’s sister Bert.

Auntie Beat and Uncle Bill:

Down at the creek. From left to right (we think): Auntie Beat, Uncle Bill, Rob, Pat, Doug and a neighbour or visitor:

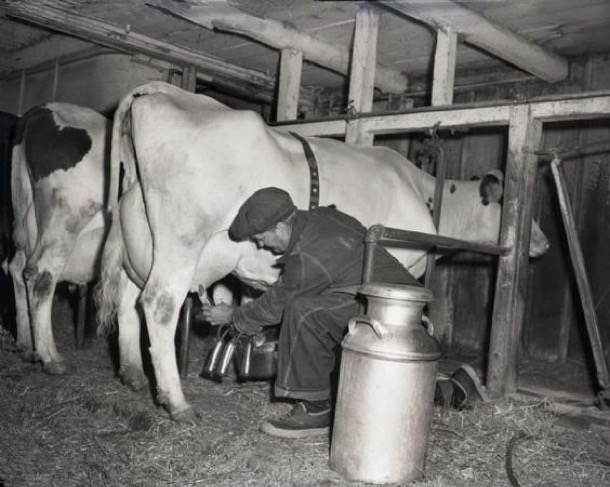

When I picture the farm and its people, in the 1950s, I see Auntie Beat and the men in layers of worn out hand knitted woollens: shapeless jumpers and cardigans, beanies, fingerless gloves, scarves. Auntie Beat wears heavy woollen skirts, thick stockings and socks. By the back door are a row of huge gumboots. Everywhere out side the house is mud, and away from the immediate house and garden, they all wear gumboots. In the dairy they wear heavy canvas coats or aprons. In the house, images of checked aprons, floury hands come to mind.

The journey to the farm with four children in the back seat, or perhaps Chris on Mum’s knee, always seemed a happy and interesting trip. It was about forty-seven kilometres from Box Hill, mostly through farmland, orchards and bush, and probably took us about an hour and a half.

The first highlight was Bennett’s Cottage in Burwood Road, on top of the hill just past Station Street. The crumbling walls of the wattle and daub hut, of one of the early white settlers, still stood in a paddock. We were told all about wattle and daub and the early settlers, and it remained in my mind into adulthood, as something to be marvelled at.

The next landmark was Tally Ho Farm and Boys' Home, on the corner of Springvale Road and Burwood Road. This marked the beginning of the country as the road shrunk to a narrow strip of bitumen that ran in a straight line between orchards and paddocks to the next hill at Vermont.

It then wound its way to Upper Ferntree Gully, then a small town at the base of the Dandenongs. Our route through the Dandenongs always took us through Belgrave, Selby and Menzies Creek to Emerald. From here there were several options but the routes we took are hazy. The only clear memory for both of us is of a very lovely narrow, undulating, dirt road through the bush.

Woori Yallock Road:

Sefton Park, as The Farm was named, spanned the road. The creek flats, which were on our left as we approached the farm, ran down to the Woori Yallock Creek that flowed alongside heavily timbered hills. These were the jewel in the crown and were known as ‘the flats’. At this point we could get a glimpse of the dairy and the roof of the house. White painted fences bordered the drive and framed the gateway of the cypress-lined drive to the house. The house, dairy and sheds all sat on a small hill probably an old levee bank of the creek, so the drive sloped gently up to the house.

As we piled out of the car, the farm dogs under the cherry plum strained at their chains and yapped, and Auntie Bert and Beat could be glimpsed walking up the garden path wiping their hands on their aprons. Greetings, hugs and queries about the journey over, we adjourned to the kitchen for afternoon tea. The house was entered from the back door that opened into a wide spacious hallway from which opened the bathroom and the hallway leading to Auntie Bert’s room and the boys bedrooms. The kitchen was occupied by a very large rectangular kitchen table where most of the food preparation and meals etc took place. At the far end under a window was the kitchen sink and in the chimney opposite the door was the wood stove.

The toilet was in an unpainted wooden building down a winding path from the house. The heavy wooden door was held shut with a small rectangular block of wood which turned through ninety degrees. It was dark, smelly and spidery inside.

On a wide, flat platform facing the door was a handmade heavy circular lid, topped with a wooden handle. The bench was too high for little girls to be able to properly lift the lid, so it was wriggled sideways to reveal a deep dark chasm.

Mounting the platform and inching back so that one was seated over the fetid depths was an act of courage. I remember my legs stuck out straight in front.

Dismounting required wiggling forward and revealing once again the dark depths.

We had toilet paper in our much less terrifying outdoor dunny at home. Here, there were squares of scratchy newspaper on a string.

It was important to remember to replace the heavy circular lid, and then to wash our hands in the bathroom, just inside the farmhouse door, with a thick slab of yellow soap.

In winter of course the house was toasty warm. We all sat down to afternoon tea and ate scones with lashings of farm cream and all washed down with copious cups of tea and farm milk of course. After news was exchanged the ritual of the visit dairy to watch the milking and the pilgrimage to the pigs took place.

The main business of the farm was dairying. They had a herd of dairy cows: jerseys with huge liquid eyes. There were farm dogs, but the cows made their own way up to the dairy, in the late afternoon, following muddy, well trodden paths through the paddocks.

In turn they filed into the dairy, and into one of the six milking stalls, and the noisy diesel powered machine cranked up. The teats were washed with an old towel in a bucket of soapy water, a loose chain was put under the tail around the rump, and a set of shiny metal tubes was attached to each udder, with audible sucking sounds.

Each cow chewed contentedly on food in a trough at the back of the stall, as her udder, hidden by the tubes, pulsing rhythmically. Eventually she would finish, be set free and make her way out the back of the shed and another would plod in to take her place. I remember being very impressed by the way the cows seemed to know what to do.

The only glimpse of the milk itself was in a high up glass ball into which the milk pulsed as it was pumped into the room behind the dairy.

After the last cow had made her way back out to trek slowly down the hill, the clunking machine would be turned off and the clean up would begin.

Dairy farming involves the sad business of poddy calves, separated from their mothers and sold. We remember calves being fed from a bucket, but not the significance of this.

The dairy business sold cream, separated from the milk in a high tank. This used centrifugal force to collect the lighter cream and send it through a separate channel. We remember the whole milk being pumped into the tank along a wide, shallow chute.

The remaining skim milk was used on the farm to feed the pigs, Auntie Beat’s pride and joy.

The milk was mixed with some sort of grain to produce a mash, which was poured into troughs for the pigs.

Our visits always involved trekking down to the smelly pig sheds, where huge sows sloshed around or lay on their sides, in spacious, but muddy pens, surrounded by little pink and brown piglets. They also had access to the surrounding paddock: it was a far cry from modern factory pig farming, a cruel and hateful process. I can’t find in my memory any emotion connected to the actual pigs. Sue remembers cuddling the hand-reared orphan piglets in the kitchen by the slow combustion stove and the boar, who lived permanently in the muddy paddock.

We’re not sure exactly how many pigs there were, but there were about four pens, where the sows and piglets were. Possibly they were only kept in those pens when they had their piglets, and roamed in the paddock the rest of the time.

I remember Auntie Beat lifting the massive lid on some huge ground level tanks to proudly reveal a seething mass of fat maggots, her clever way of dealing with the pig excrement.

I remember our mother’s wry amusement at Auntie Beat’s enthusiasm for the pigs. Apparently she had been an elegant and sophisticated lady in her earlier life. But this version of Auntie Beat, sloshing around the pigsty in her gumboots and several layers of shapeless cardigans was all we knew.

Mostly I remember the smell!

Quite often while the grown ups were chatting we were allowed to play in the hay shed with Julie. It was such fun! The hay shed was a traditional barn shape and covered in red painted galvanised iron, peeling. Most of the painted surfaces at the farm appeared to have peeling paint. It was open on one side, so it was light and airy and a child's paradise.

Rectangular bales of hay were stacked to the roof along the back and then in descending tiers. Chooks and cats played, scratched and slept in there too. We climbed all over the bales up to the roof, built cubbies and played.

There were a few variations to this routine that I can remember. Once we went shooting on the flats with Dad and I was allowed to have a shot at a rabbit and on a few occasions we went blackberrying. We also went for a big walk up the hill over the flats. An exciting ride down to the flats in the tractor trailer and over rickety home made wooden bridge, was followed by what seemed like a big walk up the wooded hill to the top. The best adventure though, was the day we visited during hay cutting season. I can still picture it. It was a lovely clear summer day. We watched the dry, cut grass baled up into the neat rectangular bales we were familiar with in the hay shed.

Towards evening, after the milking, it was time to leave. Laden with fresh cream, milk and flowers, we made our way up the garden path to the car. After many warm hugs, we began the journey home. Often it was dark by the time we passed Emerald and it was at this point in the journey that we sometimes sang. The Ash Grove features in my (Sue’s) memory, as it was hard for me to get to the high notes. The rounds we sang were also fun and a very good activity for tired children squashed into the back seat.

‘The Farm’ visits remain in our memories as fun, and an adventure in our simple lives. It was not only because we played in hay shed and joined in the farm activities, but because we were very fond of Auntie Beat, and particularly Auntie Bert.

‘The Farm’ is still a working property today. Rob remarried, another Pat while Bert and Beat were still alive and living in the old farm house.

Rob and Pat built a new house in the front paddock, had a family, and took over the working of the farm. Tragically, Rob was killed in a tractor accident when the children were still young. Pat stayed on, running the farm, looking after the children and working part time as a nurse.

We have visited infrequently since Bert’s and Beat’s deaths, briefly making contact again when Jono and Sue kept bees in the top paddock.

This photo was taken in 1983. In the background is the old farm house. Back row from left to right: pregnant Margaret, John, Jono and Alice, our mother.

The farm is in good hands. Pat stopped the use of fertilisers in the paddocks and the dairy herd became a totally organic operation. Today one of Pat and Rob’s sons runs a very successful organic vegetable growing business, supplying top Melbourne restaurants with fresh produce. Beat and Bill would be pleased that today one of their great grandsons still works the farm.

Here is an aerial view of the farm today. The original farm buildings are in the bottom of the picture. Pat’s house is on the other side of the drive, closer to the road. Today it is surrounded with greenhouses.

Comments