The Built Environment - Box Hill

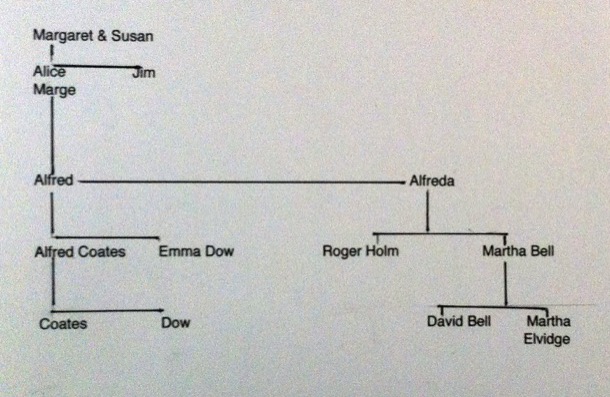

We grew up in Box Hill South in close proximity to Surrey Hills where our family has had an association for five generations. 28 Moore Street was our family home.We all spent our childhood and early adult years there, before moving out on our own. The family ventured out into Box Hill in 1946 when our parents bought a block of land in a new subdivision. They paid one hundred pounds plus ten pounds in taxes. Jim and Alice also looked further out in Donvale, where, for a fraction of the cost, they could have purchased two acres of bush. Unfortunately this was not an option as there was no public transport and we did not own a car.

After the war, Box Hill South was opened up for new housing. The City of Box Hill revised its land valuation system and residential subdivision started to boom across the municipality. The small holdings of mixed farming and orchards, were quickly replaced by the unmade road network of the subdivisions. Electricity and gas were provided, but no sewerage until the 1950’s, so it was outside toilets for all.

Our parents could not afford to have the house built, so Jim decided to build it himself. He bought a book on basic carpentry and the tools, all hand tools of course, and proceeded to build. The house is still there today, straight as a die.

It was a very liveable and rather nice design, set on stumps, weatherboard cladding and with a low slung, pitched roof. It had the standard three bedrooms ,one bathroom, kitchen, dining room, lounge room and laundry. When first built there was an outside toilet attached to the single garage that also had a chook pen attached to it.

Over time, the surrounding paddocks filled with houses and our house changed a little too. The view of the Dandenongs from the french doors in the lounge room disappeared, the toilet moved inside and our grandparents built a flat on the back. The addition of the rumpus room and flat spoilt the spaciousness of the living rooms and the back garden. The old weatherboard garage, toilet and chook pen were removed and a new double garage and new chook pen took the new additions to the back fence.

Little appears to have changed externally to the house since Mum sold it about 1981.

When we were children, Wattle Park itself consisted of large trees with mown grass underneath, like a traditional park, but with native trees and grasses. It was owned and maintained by the Tramways Board, responsible for the tram system in Melbourne. The Tramways brass band played in a rotunda every Sunday in the park. Nowadays those grasses are no longer mown. It looks much more like remnant bushland.

The 137 acres opened as a public park in 1917.

The chalet, designed and built by a Tramways architect, opened in 1928. it was promoted as a dance hall and wedding reception venue and, amazingly, it still is. It is listed on both the Heritage Victoria and National Trust Registers.

Our own parents’ wedding reception was held there in 1945, after they had been married at the Wyclif Surrey Hills Congregationalist Church in Surrey Hills.

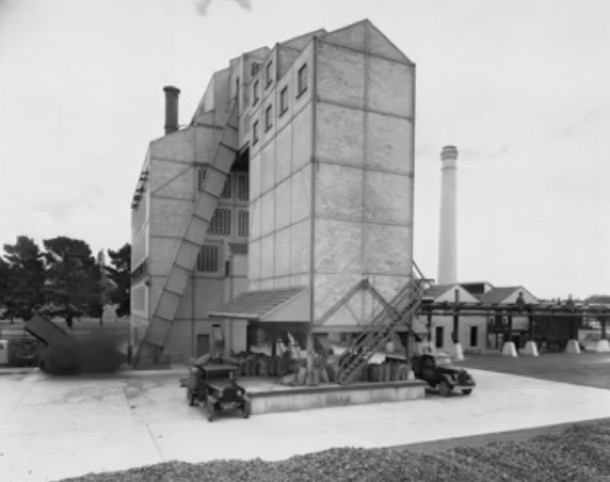

Box Hill Gasworks is now gone, but it was an important part of our parents' history. It was built early in the history of Box Hill:

7/1/1890 The Argus

Some twelve months ago the Nunawading and Boroondara councils granted permission to Mr. Thomas Coates, hydraulic engineer, to lay down gas mains in the streets of the two shires. Mr. Coates purchased an eligible site near Elgar road, Box Hill, upon which to erect the gasometer and the other necessary buildings. At the present time all the mains have been laid down in the shires named, and Mr. Coates is now in a position to light up Surrey Hills and Box Hill with gas. The local works are of such a nature that Mr. Coates contemplates being able to supply the wants of the district for many years to come without enlarging the gasworks. Last night a trial was made in Box Hill and Surrey Hills, when the corporation lamps were lit with gas for the first time. Illumination works were erected at the intersection of the leading streets. The trial was considered a very favourable one, the gas burning bright and clear. In connection with the lighting of these shires with gas a public banquet will be held in Surrey Hills next Monday night.

Over time three gasometers were built.

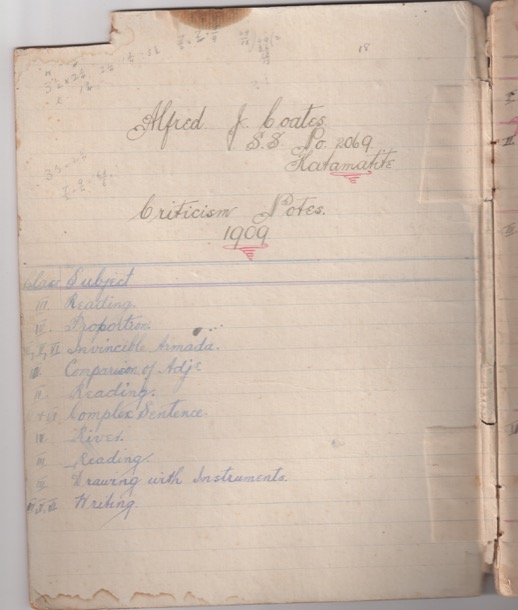

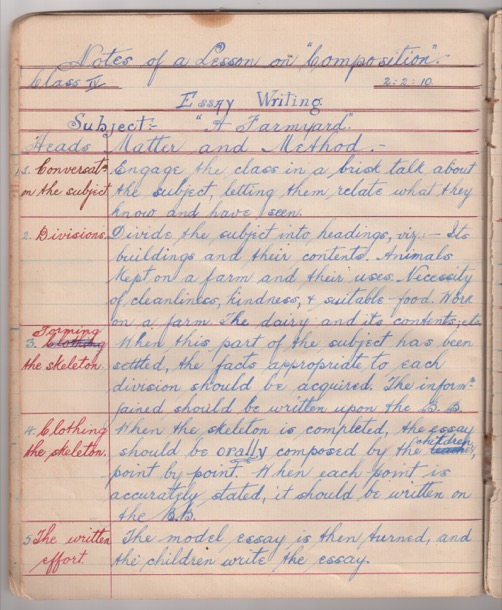

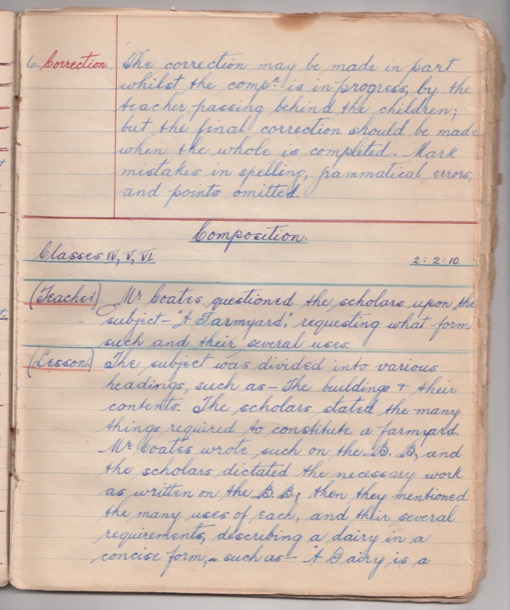

We don't know exactly when Jim started work at the Box Hill Gasworks, but in 1945 he left the Maribinong Munitions factory, where he had spent the war years. It was that year when our parents married and Jim moved into his in-laws’ Surrey Hills house. Soon after, he started work at the gas works as an analytical chemist. He worked there until began teaching in 1954.

Sue remembers him riding his bicycle to work, and later, a motorbike.

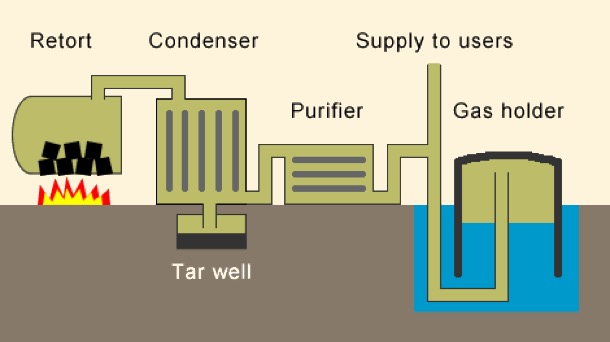

He worked in the laboratory, doing things like checking the calorific value of the gas.

Melbourne’s gas supply was made from Latrobe Valley brown coal, sent by rail to the various gasworks, owned by Colonial Gas Company. Box Hill was one of the biggest. As Melbourne expanded after the war, the demand for gas meant that the various gas works were very busy.

But, by 1960, substantial natural gas reserves had been discovered around Australia. Over the next five years all the Gas plants in Melbourne had closed down, and over 1000 workers were made redundant, by the discovery of natural gas deposit in Bass Strait. Over one million gas appliances in Melbourne were converted to natural gas in 1968. We remember the conversion time. There must have been plenty of publicity. Natural gas has no smell, and, for safety, they put in an additive to make it smell quite strongly. The flame was slightly different, but all the existing burners still worked.

The Gas Works are long gone. Box Hill Institute now occupies the site.

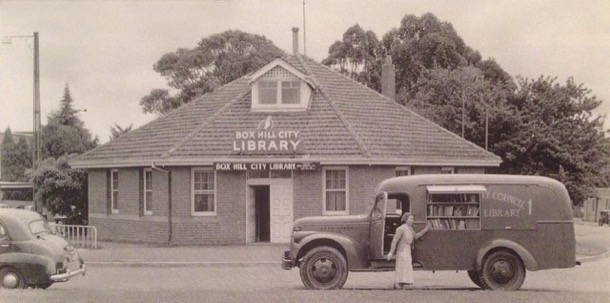

One of the fortnightly highlights in our simple lives was a trip to Box Hill Library. We loved this excursion, as we spent many hours reading on our beds. Books were expensive and we only owned a few. We had to rely on the Library so that we could finish our favourite series like Famous Five and the Billabong Books.It was very exciting if the next book in the series was on the shelf.

This small brick building was opposite the Town Hall at the end of the shopping centre. Whitehorse Road always had a wide, tree lined median strip, as it does today, and the library was right in the middle. It was later replaced by a grand modern library, but the small brick building is still there.

In our childhood, a trip to Box Hill shopping centre was quite an excursion, involving a four mile walk. In 2019 Google Maps says it takes thirty two minutes, but with small legs and a pusher as well, maybe it took a little longer. I remember it was fun and not arduous at all. The route went through suburban streets until Canterbury Road and from there it was ovals and open ground.

Box Hill Brickworks was one of the best sights on the walk to Box Hill, as the brickworks were still in full production. We marvelled at how small the men and carts were at the bottom of the quarry, and watched the procession of carts pass up and down the steep rail track to the actual brick works.

Box Hill Brickworks was founded in 1884 and was one of fifty or so brickworks throughout Melbourne, producing bricks, tiles and pipes for the building boom and ever expanding city. During the working life of the brickworks the clay was extracted from two clay holes or quarries. The first became Surrey Dive which became a popular swimming venue, but off limits to us. Sometimes however, we also gave ourselves the horrors, looking at green, mysterious waters. There were rumours of 'the dive' being bottomless and of swimmers disappearing in its murky depths. One story was of a man who took a very deep dive off the cliff side and simply disappeared. Some time later his body surfaced in Blackburn Lake, five kilometres away. No wonder we looked in awe and horror through the fence.

Today Surrey Dive is an attractive small urban lake used for swimming and remote controlled boat races.. A walking track around the ‘old dive’ and the brick works is planted with indigenous vegetation and a relaxing and attractive area.

The other clay hole was the quarry that was in operation doing our childhood. It was adjacent to the brickworks and kiln, now derelict but still heritage listed. Unfortunately no restoration work has been carried out. The kiln itself was a massive, red brick building constructed on two levels and, of course, with a huge brick chimney.

The quarry that was still in full production in our childhood, is now completely filled in. That cavernous hole in the ground is now a large mound covered in every weed known to man. On the horizon above the weeds, are the sky scrapers of twenty-first century Box Hill.

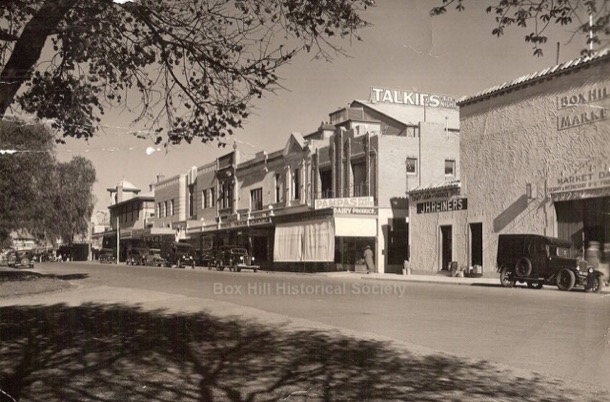

Box Hill shopping centre developed as a commercial centre, as soon as the railway line between Hawthorn and Lilydale was finished in 1862. It became an important transport hub for the eastern suburbs and beyond. During our childhood, Box Hill was the shopping destination for a big purchases. For instance, I can remember choosing a ‘walking’ doll with opening and closing eyes for a birthday present and the excitement of choosing a winter coat with a brown velvet collar. Another favourite shop was the delicatessen where such delicacies as rollmops, sauerkraut and frankfurters could be bought. Amongst the many single fronted small businesses were several large shops such as Taits haberdashery on the corner of Whitehorse Road and Station Street and Maples furniture shop. We also had a Coles variety store that sold anything from socks and singles to cosmetics, and MacEwans Hardware whose slogan was, “You can do it with McEwans because we’ve got a million things.”

This is a photograph of Box Hill Station and the surrounding shopping precinct in the 1960s. In the centre of the photograph is the old station, that is now underground. Today, above ground, occupying the whole block surrounding the old station, is Box Hill Central and surrounding shopping malls. The signal box, the tall structure on the left of the railway gates is now occupied by the thirty-six storey golden residential tower, called Sky-One.

In the twenty-first century, Box Hill, as a commercial centre and transport hub, continues to influence the built environment around it, as you have no doubt witnessed. Officially designated as a development hub, Box Hill now sports high rise office and apartment towers. The streets we once drove down are now shopping malls, the station is underground, the railway gates are long gone and the strip shops have been replaced by a multi storey modern shopping centre. When we were children the shopping crowds were white and Anglo-Saxon. Today they are predominately Asian and the shops and restaurants reflect the change in population.

When we, as a family, first started going to the local Presbyterian church, it was called Presbyterian, Wattle Park. We had PWP embroidered on the front of our blue gym uniforms. This was before the advent of the Uniting Church. Church services were held in a cream brick building, called Forsythe Hall.

Attached, behind it, was an older little wooden building. During our childhood, this wooden building, Staley Hall, was used for a kindergarten during weekdays. In the evenings, various groups used it, including church boys’ and girls’ clubs (PBA and PGA) and the mixed club (PFA- Presbyterian Fellowship Association), we went to as teenagers. Sue and I both learnt to dance there, and I broke my front teeth on the heater in that room.

We have many memories of Forsyth Hall… dances, performances, Saturday afternoon movies, gym classes and, of course church services.

Both our parents were Elders of the church. Our mother taught Sunday School, our father ran the PFA for a while, and was on the board of management. The church was their only real friendship group, and was the only social life we had, as a family.

In the early 1960s the church community began the project of building a new church on the site. The size and scale of the project was a source of much disagreement between our father and others on the management committee.

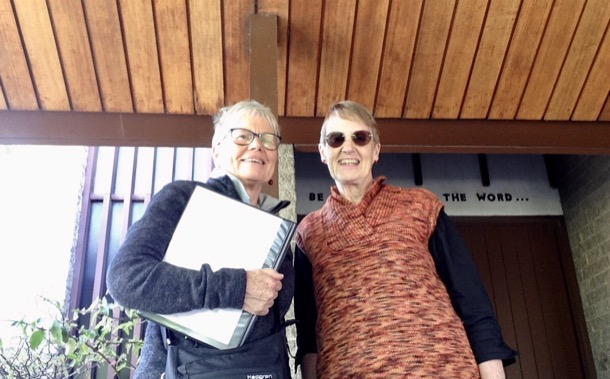

In the end, a very grand architect designed building was commissioned. The new building was designed by well known architects Chandler & Patrick. An 1887 pipe organ was relocated from a church in Melbourne and extensively rebuilt. The new church, renamed St James, opened in 1965.

I loved it, because I sang in the church choir, and it had a choir loft at the back and great acoustics.

The buildings are still there. Sue and I visited as a detour on our “back to school” walk in 2016.

Auntie Bert, a "sterling character"

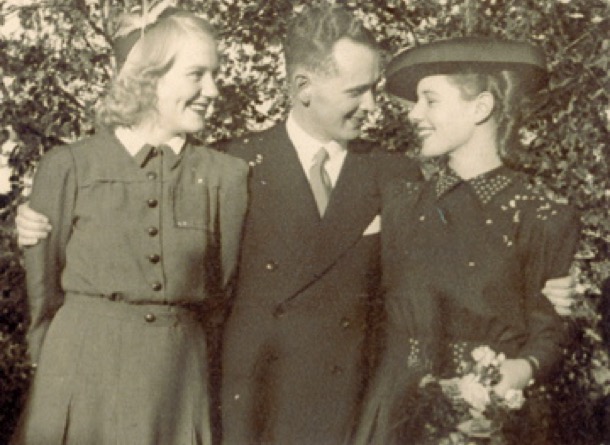

These three young women are our grandmother Alfreda on the left, with her two younger sisters, Beatrice in the middle and Berta on the right.

Alfreda’s set jaw and determined look reflect her independence and demand for an education. I fancy I can see both the rebel and the farmer in Beatrice’s broad face. But look at the gentle, faraway, passive prettiness of Berta. What experiences are already clouding her young face?

About ten percent of the whole of Australia’a population, the country’s young, fit men, set off to war in 1914. More than half of them were killed, gassed, wounded or taken prisoner. There was no such diagnosis as “post traumatic stress”, but we can extrapolate from the modern experience of returning soldiers.

What happened to the equivalent ten percent of young women, who, in different circumstances, would have been marrying them and having their babies?

Our Auntie Bert became one of the many “maiden aunts” of that very specific generation. The family lore is that she “had opportunities” to marry but “chose to stay in the bosom of her family”. We do not know what the reality of her young life was. Had she been a boy, she would have been one of the 417,000 men who enlisted. One would presume that virtually all the young men she might have had a romantic interest in… brothers of her friends, boys from church, at work, on the train, in her neighbourhood… nearly all would have been absent for four years from when she was 18 until she was 22.

Berta Holm was born in 1896. Her childhood and early adult life was spent in St Kilda.

The family story is that Berta and Beatrice unlike their older sister, Alfreda, did not hunger for an education.

Alice and Marge said this in quite a disapproving tone, which made us wonder about the accuracy of the statement, that Auntie Bert left school at Grade 4, declaring that she would prefer to help her mother at home. In Grade 4 she would have been nine or ten!

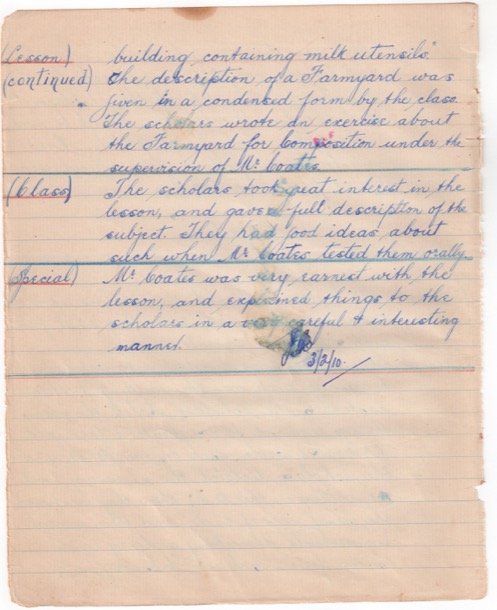

At the time Victoria was a progressive state and proud to be the first Australian state to create a system of free, secular and compulsory education. This legislation introduced in 1872, required all children aged 6-15 years to attend school unless they had a reasonable excuse. Schools were built, and a system of inspectors employed to enforce compulsory education. Fines for non-attendance were five shillings and increased for further offences. Did Auntie Bert leave school at the tender age of nine or ten? We think it more likely that she attended a State school, maybe unwillingly and, after trying a private school for young ladies, left at the age fifteen. Their disapproval of the lack of enthusiasm for education, compared to their own mother’s, probably colours the story about their aunt. The view of Auntie Bert we were brought up with, was that she was good with her hands, but, to soften and elevate this statement in true Holm fashion, it was followed by, she was a superb craftswoman and much in demand: not academic but exceptional.

Some time after she left school Berta went to work in Flinders Lane.

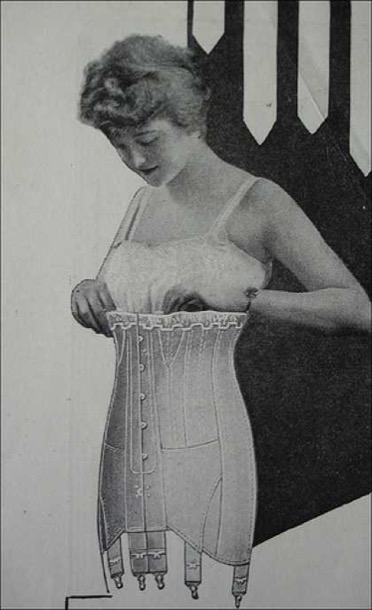

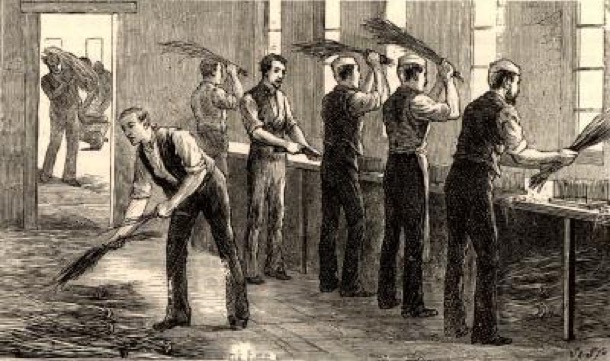

At that time Flinders Lane was the centre of the ‘rag trade’ where many Jewish firms had their businesses. Amongst them was Slutskins, for whom both Berta and Beatrice worked doing ‘white work’. Whitework embroidery is the general term for hand embroidery worked with white threads on white fabrics. It is one of the most elegant and timeless styles of embroidery and was used on underwear, night gowns, table linen, handkerchiefs, baby bonnets, christening gowns and many other small items.

After some experience in this area Berta became forewoman, in charge of a group of other women.

We only have Alice and Marge’s childhood recollections from which to piece together Berta’s life.

In early 1925, when she was twenty-nine, perhaps moving away from her parents’ home for the first time, she left her job, probably that responsible position as forewoman. She went, for an unspecified time, to the country, to help her married sister with a toddler and a baby, and to help serve in her brother in law’s hardware shop.

Alfreda had given birth to Alice, our mother, in 1923. She had had a terrible time, alone, during her first delivery, resulting in the death of the baby. We don't know anything about Marge’s birth or the subsequent few years, except that they were quite near to family help. But when Alice was fifteen months old, Alf and Alfreda moved to Bacchus Marsh. Alfreda was “weak from the birth”. The descriptions of her crying, while scrubbing the floor and having to spend whole days in bed, apparently requiring the help of her unmarried sister, makes us think of post natal depression.

Alf too had what we would today call “mental health issues”. He was a gentle, quite scholarly person, and the business venture in Bacchus Marsh, on the eve of the Great Depression, took a toll on his health. It is no wonder Marge and Alice remember Auntie Bert as a tower of strength and support.

In 1928, the old dry house they had been living in caught fire. At the top of the burning staircase were the little girls in their nighties, Alf sedated, because he was in the midst of a “nervous breakdown”, Alfreda, reportedly trying to find her stockings, and Bert, who carried Alice down the stairs. Marge was carried down by her father, finally awake.

The destitute family were taken in by “the Pierces”. Nell Pierce was a lifelong friend of Auntie Bert. Did they meet there at Bacchus Marsh? We don't know.

The family stayed on for at least a year in Bacchus Marsh, but Berta moved back to Melbourne, once again moving in with her parents, probably her only option.

Now in her early thirties and unmarried Berta must have turned her attention to a job. As far as we know this is when she decided to start her own business as a dressmaker. At first she worked from her bedroom, building her business and reputation.

The business was eventually profitable enough to allow her to move to premises in Riversdale Road, Middle Camberwell and then to Burke Road in Camberwell, just over the junction.

I can remember the junction premises quite vividly. It was one big room on the first floor. Big windows looked out onto Burke Road, letting in light and sunshine that fell on the big work tables. Several dressmakers dummies stood in the corner where the fitting room was screened by curtains. It seemed a very busy place.

The big tables, that dominated the space were covered in the paraphernalia of dressmaking. There were several sewing machines, many reels of sewing cotton, several pairs of big dressmakers shears, other dressmaking scissors and many tins of pins. Rolls of fabric and garments in various stages of construction took up the rest of the table space. Another woman was sewing at the table, presumably an employee, so business must have been good. We were probably there for a fitting, as Auntie Bert made ‘good clothes’, for Mum. These beautifully tailored clothes were worn to Church and were for special occasions, including weddings:

She also made us beautiful clothes including these woollen dresses:

Auntie Bert had an account at Ball & Welch, a prominent department store in Finders Street, Melbourne. She needed an account for her business and a reliable source of good quality fabric for her clients. Its four floors occupied one third of the total block and stretched between Flinders Street and Flinders Lane.

Its many departments included gloves, umbrellas and handkerchiefs, fabrics, furniture, china, millinery, furs and corsets. At one time twenty-six assistants were devoted to the sale of lace alone.

Members of the family were generously given access to Auntie Bert’s account, making it possible to buy items on account and pay later. This was very useful at times, as there was no such thing as Credit Cards. At the end of the month, Auntie Bert sent out letters to all those who had used the account, and we reimbursed her by cheque. This was probably quite a task, not only the arithmetic, but also the sending out of all the individual letters.

I can remember enjoying trips to Ball&Welch. The lifts were staffed by attendants in uniform who recited the list of items available at each level as the lift rose between floors. Parcels were wrapped up in brown paper and string, on huge wooden counters. The expert shop assistants were reserved, formal and a little forbidding to a young child. The exchange of payment was quite a process. The shop assistants' job was to serve the customers, not handle the money. When payment was made, it was placed, with the hand written docket, in a metal canister that went shooting on wires across the departments and then upstairs to the Accounts Department. The docket was checked, change inserted, a receipt written and the canister whizzed back from whence it had come. Transaction complete.

The cash-ball system worked reasonably well, but the rails were intrusive and the interior layout of some stores did not allow certain counters or departments to be connected by inclined tracks. The ingenious Lamson then hit upon the concept of the “aerial railway” and set about tinkering with a gondola-like design, which became known as the wire-line or cable-carrier.

By the late 1880s, sales staff could secure cash inside a small wooden jar or canister, suspended by wheels from a taut wire that ran overhead from the sales desk to the cashier’s station, which was typically a cage-like booth situated in the center of the store. By tugging firmly on a spring-loaded cord or lever known as the “propulsion,” the canister would be catapulted along the wire, reaching its destination in mere seconds.

The cashier could then “return fire” with change and a receipt. Cashiers who worked in booths on levels above the sales floor could simply release the canister and let gravity return it to the appropriate counter.

Ball and Welch closed its doors in 1970, the end of an era .

Berta’s sister, Beatrice had taken up dairy farming in the early 1950s, near Cockatoo, in the Dandenong Ranges. The bulk of the work was done by her husband, and three sons. In 1955, the wife of Rob, the middle son, died, leaving a baby daughter, Julie, to be raised by her grandmother.

Into the breach stepped Berta. She moved into a small bedroom in the farm house, and became a second mother to Julie. We remember her room. It had been part of the farmhouse verandah, and the whole room was about twice the size of the single bed. It was neat, sparse and dark.

Our memory of Auntie Bert at the farm is solely inside the farm house. Unlike Auntie Beat, who mucked out the pigs, wearing layers of old jumpers and a woollen beanie, Auntie Bert was always nicely dressed. We remember her in well-cut woollen skirts, stockings and heeled court shoes, with classy jumpers and cardigans. We picture the two of them in the kitchen, both wearing aprons, turning out scones and cakes on the wood stove. Auntie Bert became a permanent and valuable member of the family, looking after the “boys” and Julie.

While her main home and focus was life at the farm, Auntie Bert continued, as she had her whole life, to be the family helper and nurse. She had looked after both her own parents in their final years, and she came to live with us to help out with her elder sister: our Nana, Alfreda, who had dementia. We remember her as a quiet unobtrusive presence in our home. A few years later she came again and helped with Alf, our grandfather, in his final weeks.

So Alice saw first hand, the skill and care of Berta’s nursing:

Apart from staying temporarily with other members of the family, usually to help out during family crises, Berta lived there at the farm, until her death in 1976, aged 80.

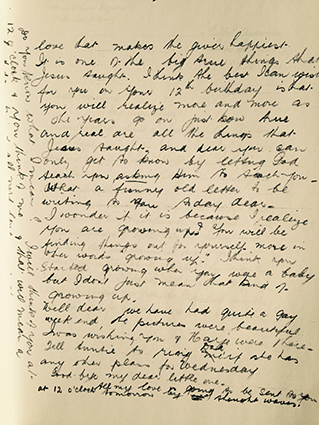

Alice reflected on Berta’s death and the simple generous life she lived:

From left to right, Nana, Auntie Bert and Alice:

The Croydon Years

When the Coates family moved to Croydon it was the beginning of the Great Depression and many men were out of work. To complicate matters, Alf had been in partnership in a hardware business in Bacchus Marsh that had burnt down. Not only was the fire a personally traumatic experience for the family, as their house had also burnt down, but the business was not insured. As manager, Alf was responsible for the lack of insurance. He was therefore "lucky indeed" to have the job as the hardware store manager at the Croydon Timber Yard. He was on a reduced salary as recompense for the losses of the other Bacchus Marsh partners, who now owned the Croydon business.

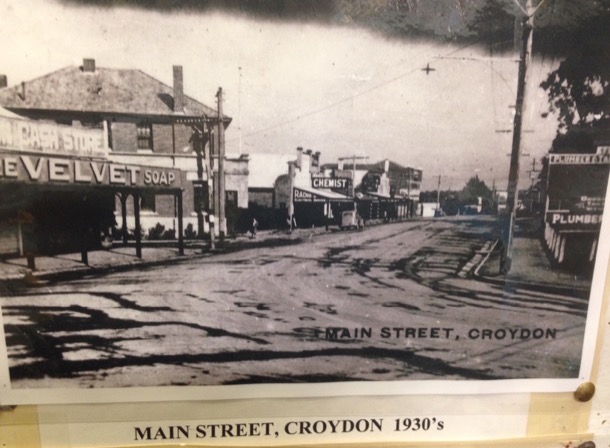

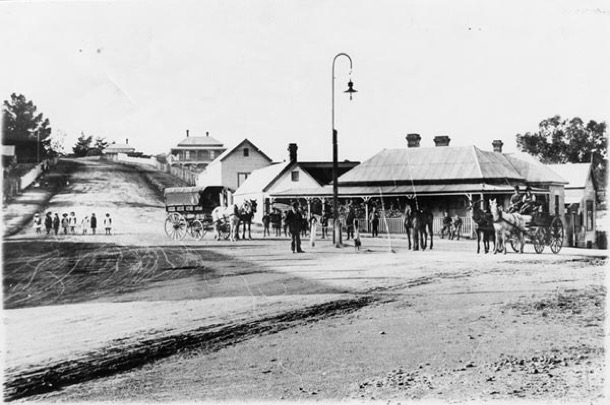

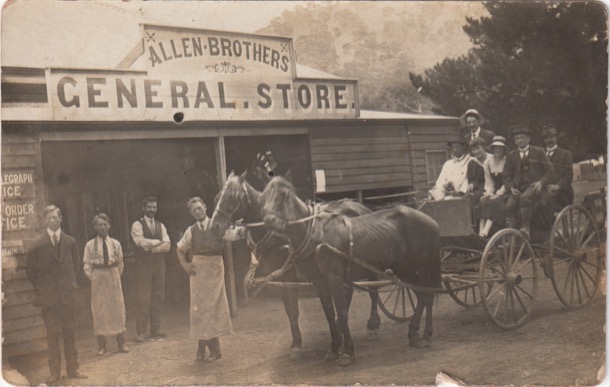

Croydon was at that time a pretty, country town, connected to the world by the railway that ran, as it does now, from Flinders Street to Lilydale.

White settlement had reached Croydon in the 1850’s, as timber cutters arrived seeking new sources of timber for the needs of rapidly expanding Melbourne. Many small, and a few large land holdings were taken up, and fruit trees were found to flourish in the area.

The town that the Coates family found, spread out from the railway station. Businesses and shops were strung out along the long, wide, slightly curving main street. The Dandenong Ranges made a lovely backdrop to the town that was surrounded by small farms, orchards and bushland. Home for the Coates was a small house, painted battleship grey, in Hewish Road, very near the corner of Main Street. This was the wrong side of the tracks. The expensive houses were built over the railway line in Wicklow Avenue, extending up the hill towards what is now Maroondah Highway.

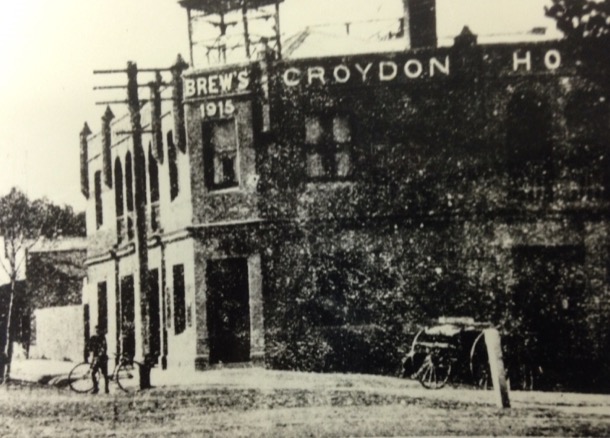

They remember their house as having a beautiful backyard, graced by an enormous Mulberry tree and a large vegetable garden. There was a cow paddock on one side of the house and the Wine Hall on the other. Hewish Road at that time was unmade, covered in hard stone embedded in the clay. The Coates were right in the business end of town: Cook’s Grain Store was directly opposite and Croydon Timber Yard, not far away, also in Hewish Road. Not only did this fiercely teetotal family live next to the Wine Hall located on Main Street corner, but on the other corner was the Croydon Hotel. These two establishments loom large in their childhood memories, as they were the source of the moaning drunken men that they sometimes heard outside. Occasionally their father had to take the men home.

Croydon Hotel:

Croydon Wine Hall:

Alf worked weekdays, Friday nights and Saturday mornings at the timber yard. Once a month he also drove the truck to the wharves to collect timber.

Money was tight, especially as Alf and Alfreda wanted their girls to have a decent secondary education at MacRobertson Girls' High School in Albert Park. One-third of Alf’s wage went on rent and by the time bills were paid and weekly expenses were covered, there was not much left over. At secondary school, fees were charged, books and uniforms would need to be purchased and weekly train fares paid for. Daily life therefore included the care of livestock and the processing of milk and eggs: all quite time consuming.

As well as their home grown vegetables and fresh eggs, the Coates family produced their own milk and cream.

All was not hard work however, and the Coates’ kitchen, warmed by the one-fire stove, was the venue for cups of tea and chats, many of them about cricket. In the picture, Alf is second from the top left:

Marge and Alice had a very happy childhood in Croydon. They played often with the Cook sisters, Yvonne and Margaret, who lived opposite. The Cooks had once owned the Croydon Timber Company, Alf’s employer.

Their house was on the other side of Hewish Road, next to the hotel. Connected to the Cook’s house was the grain store, which was now the core of Mr Cook’s business. There were delivery horses in a nearby stable too, and cows in the paddocks behind. The grain store was packed with bags of chaff and grain. The girls spent many hours playing in there, climbing right up to the roof.

One happy memory is of “penny concerts”. Hours of preparation: planning, costume making, and rehearsing, culminated in a concert performed on the Cook’s wide side verandah. This seemed to be mostly in the summer holidays, when the Cook girls’ cousins came to stay. Marge and Alice sang part songs, often Elizabethan madrigals they had learnt at school: Alice singing soprano and Marge, alto. The adult audience (probably only their parents) paid a penny to attend.

Alice remembered playing a sort of scavenger hunt, following written clues to find a prize. “Next clue under the camellia bush”.

She also remembered marbles, played in the dirt on the side of the unmade Hewish Road. When Sue and I stood on the same spot in our Croydon visit, we could hardly cross Hewish Road, for traffic! In the 1930s, it was a quiet gravel road with no gutters and unmade footpaths.

The Coates and Cooks lived opposite each other, and used to signal out of windows at night across Hewish Road. They planned, but never carried out, midnight feasts.

The wild games and excitement of playing with the Cook contrasted with the much more demure and restrained Hebbard girls. Pam and Honor Hebbard were the daughters of Frank Hebbard, the Primary School Principal, and friend of Alf and Freda. Their huge library of books were available for Marge and Alice to borrow, and the garden was a delight to play in. The Hebbards lived up on the Hill, at the top of Kent Avenue, which wound up to what is now the Maroondah Highway, through foothills bushland. A favourite activity with the Hebbards was to wander this bushland looking for native orchids. The remnants of this forest are much prized today, though much of it is degraded, and many of the species of orchid are now only to be seem in a museum.

Visits to the beach, during Marge and Alice’s Croydon years, were limited to School and Sunday School picnics. But they did learn to swim. They would go by train to Lilydale, where there was a huge concrete tank, right on the side of the Olinda Creek. Fresh water would flow in and out with this quite large perennial creek. Alice remembered Mr Hebbard lining them all up along the side and getting them to enter the water with a shallow dive. Nowadays the pool has become a more modern outdoor pool, but it’s still in much the same place.

Friday night shopping was another form of fun. Marge recalled it as a chance for everyone to parade up and down the street. Alice remembered buying “sixpennorth” of lollies and sharing them out. It was a simple life for these country kids. It is notable that, three years apart in age, much of their leisure time was spent playing together.

Marge and Alice of course went to Primary School during these years at Croydon, Marge as far as Grade 8. We will spend more time on this important topic at a later date. Suffice to say, at the moment, that their parents’ friend, Frank Hebbard was the Principal, and he ran a very enlightened, rich educational program, in which the girls flourished. The Croydon Primary School has new premises these days, but the old buildings are still there, now occupied by a Community School.

Family entertainment included hikes from Croydon to Kalorama, and visits to friends, the Cheongs. They were a wealthy and prominent family in the area. At our visit to the museum in Croydon we found many mentions of them, in particular their importance to conservation of remnant foothills vegetation. Even now Cheong Wildflower Reserve, near Croydon, still fulfils that role.

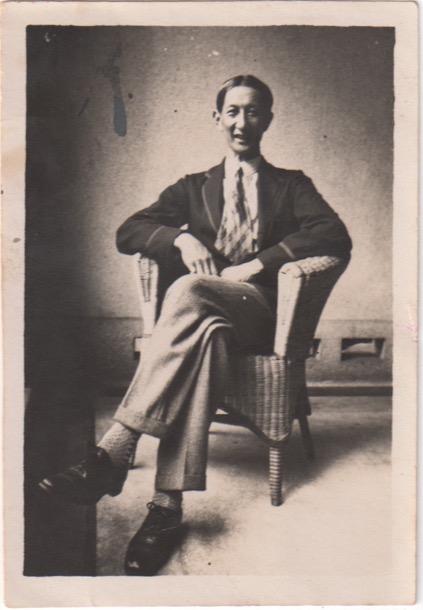

Mr Cheong, from our mother's photo collection:

In their leisure time, many happy hours were spent in the Coates’ warm kitchen, “yarning’.

Even though much of the good food the Coates family ate was home grown, some things had to be purchased at the Main Street shops.

The Croydon years were remembered very fondly by both Marge and Alice. They were formative years for both of them. Alice actually names the four areas of interest from those years that became her life long passions.

In 1936 the Croydon years came to an end with the death of Martha Holm, Alfreda’s mother. Presumably the family had to move back to Boronia Street, Surrey Hills to help Alfreda's sister, Berta take care of Roger Holm, now quite an elderly man. Berta was working full time at her dressmaking business. Alf found a new job in the city and Alice embarked on her secondary schooling at MacRobertson Girls’ High School.

Decade by Decade

Here is the audio of this from the recordings:

With our more modern education, we have less of a firm grasp of History, and we know that our children, and their children have, and will have, an even sparser knowledge. So we have taken the overview concept, explained a little more fully, and added in our father’s family history and other aspects we have recently discovered.

Alice and Marge finished recounting their family stories at 1950. One of our tasks in this project has been to continue on from then, and so we have done just that. We explore the nineteen fifties, sixties and seventies, linking what was happening in the wider world into our own lives.

1850-1950

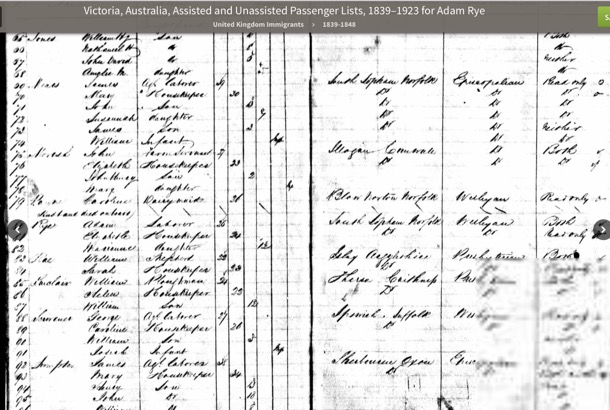

Between 1839 and 1872 our ancestors arrived in Australia.They came from both Northern and Southern Ireland, England, Germany and Denmark. All were from humble origins, having worked as agricultural labourers, domestic servants, a baker and an engineer. Some were already married and others met here.

As our ancestors built their new lives in Victoria, the First Australians had already felt the disastrous impact of European contact. There had been violent conflict, the Wurundjeri population had been decimated and the survivors relocated to reserves or camps a ‘suitable' distance away from the growing population of Melbourne and outlying settlements. In 1844, when the Bourkes took up their selection at Pakenham, they were the first white settlers in the area and the “blacks camp” by the river was noted in Catherine’s memoir. Several years later, Adam Rye, from the other side of the family, was robbed by a party of ’50 blacks’. The newspaper report notes that ‘the blacks at this time were very treacherous’.

With the discovery of gold, in New South Wales and Victoria, there was a huge increase in population and in wealth.

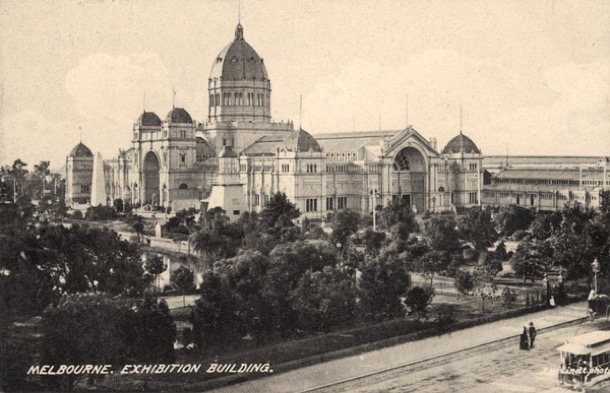

Victoria benefitted the most. Melbourne became Australia’s largest city, with a huge land boom. Grand old buildings like the Melbourne town hall and exhibition buildings are reminders of those glory days.

The increase in population, rapid development and the attraction of the goldfields led to a shortage of workers. This meant great job opportunities at every level. It also put workers in a good bargaining position.Trade Unions developed and working conditions were the best in the world. Australia was an egalitarian workers’ paradise.

Small businessmen, like publicans, bakers and lawyers, prospered with the growth in Melbourne. For farmers, it meant bigger markets, more mouths to feed. The growth in country towns, better roads and railway development made life in the country less difficult.

Engineers had a lot of work with the sudden development of infrastructure and property developers were run off their feet. Our grandfather’s grandfather, a young engineer from England, was building bridges in the expanding colony. While building the bridge across the Barwon River, his son, our grandfather’s father, was born, his birth unregistered.

Back in ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ our grandmother’s grandparents who had arrived from Belfast, were developing St Kilda: building large houses and public buildings for those who were prospering in the boom town.

On the land, our maternal ancestor Adam Rye, who had survived the attack by ’50 blacks’, settled in Geelong and worked as a farm labourer. He was later gripped by gold fever and went north to seek his fortune, only to be held up by bushrangers and lose his meagre pickings. His daughter married a German immigrant, Dau, and they settled on a mixed farm at Wandong. Here they raised seventeen children and supplied food to the growing population.

Meanwhile our paternal forbears, also on the land, were making their mark in Gippsland and North Central Victoria. In Pakenham the Irish Bourkes were building their family of thirteen children, and now owned Bourke’s Hotel. They were becoming significant landowners and community members, as they set about acquiring land, marrying their daughters well and establishing their sons on large and prosperous properties. They also served their community in local Government and built the horse racing industry in Pakenham.

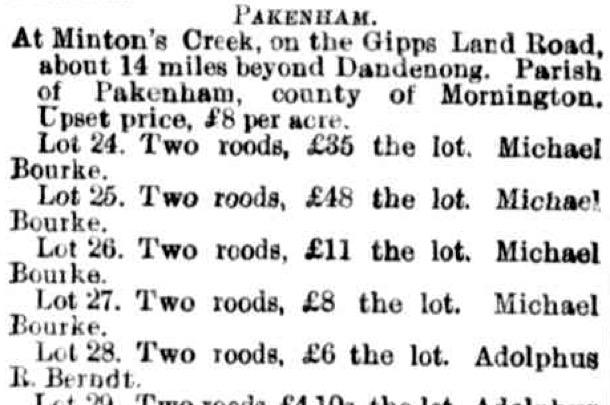

1858 Land Sales, Michael Bourke's purchases:

The MacCormacks, in North Central Victoria were also acquiring and working large grazing properties, firstly in Tallarook and then in Molesworth. They too were pillars of the local Catholic Church and community. Our grandmother was born there, at Balham Hill, pictured below.

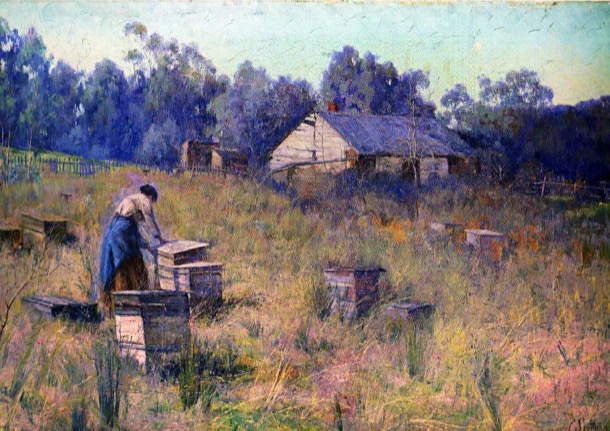

Melbourne became the financial centre of Australia and New Zealand. The Pakenham Bourkes’ fourth son, our great grandfather, was part of this world. He had moved to Parkville and built his law career in this thriving city. Australians were growing in confidence and the young nation was showing signs of an interest in its own identity. This was the era of Henry Lawson and Banjo Patterson, who wrote about the characters of ‘the bush’. At the same time, Tom Roberts and his paintings glorified the unique Australian landscape and the men and women who toiled there. This growing sense of identity and of nationhood is reflected in the moves for independence from Great Britain. During this era of optimism and hope our grandparents were small children, and their families were well established in both country Victoria and Melbourne.

Federation was achieved in 1901, and the country celebrated:

Australia was longer a colony but an independent nation. Melbourne was the largest city in Australia at the time and the second largest city in the Empire (after London). It was fitting that the new Parliament should sit in Melbourne while Canberra was being constructed.

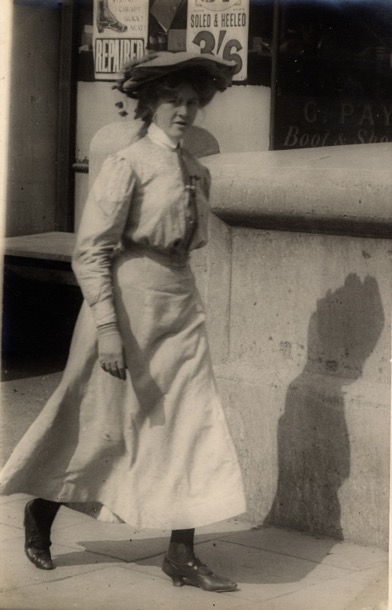

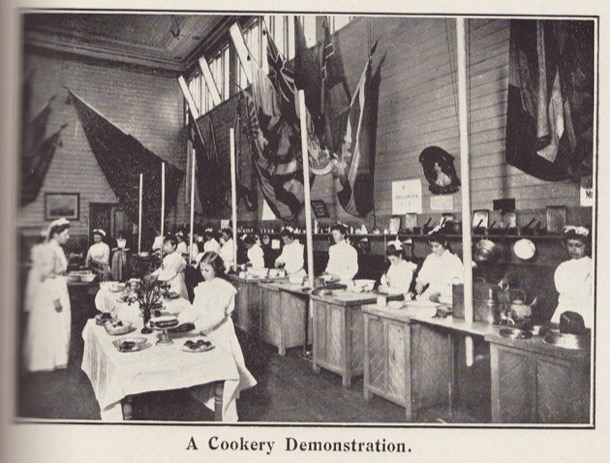

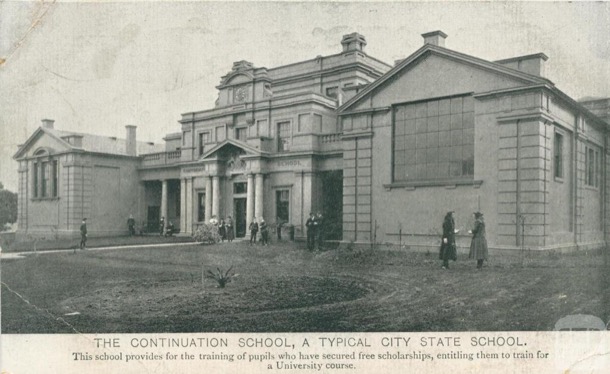

The decade after Federation saw Australian women join the battle for women’s suffrage. White men over 18 in Victoria had had the right to vote since 1858, but women were not granted this right until 1908. Our maternal grandmother, Alfreda, was sixteen when women were granted the right to vote. We imagine she would have approved. She had been engaged in her own battle to pursue her dream of further education; and during this decade she finished her secondary education at Melbourne’s Continuation School, the opening of which marked the beginning of state secondary education in Victoria.

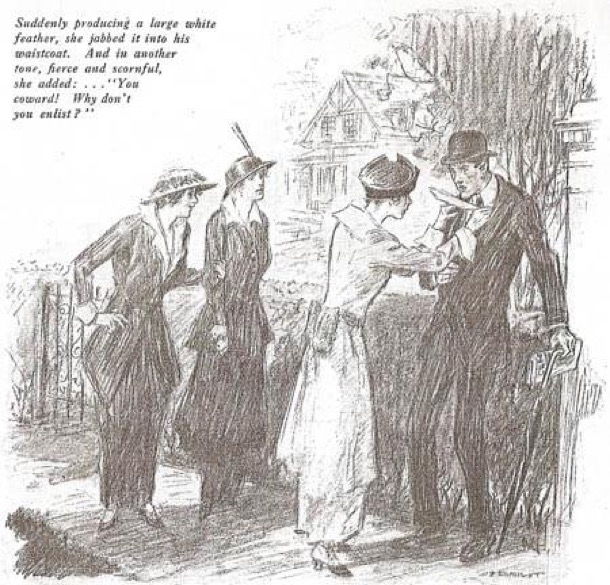

This period of prosperity, optimism, and political and social change ended in the devastation of the Word War 1. We know little of the family’s war service, but three of our maternal grandfather’s uncles served in France, and one lost his life. In the highly charged patriotic atmosphere of the time, and with mounting casualty lists, the war years must have been a difficult time, especially for our grandfather who was considered unfit for service due to ill health. He was deeply upset when given a white feather. Presumably our paternal grandfather being a country doctor, was in a protected occupation.

Our grandparents were all married at the end of this war. Our father’s parents were married in St Patricks Cathedral in a grand affair. Grace and Hugh then settled in Koroit in the Western District, where Hugh was the local doctor.

In contrast our mother’s parents were married in the Methodist Church in Surrey Hills in a small and simple ceremony where the bride did not even wear a wedding dress. At that time Alfreda was working as a teacher and Alf was working in a hardware shop in the city. They also moved to the country, soon after: to Eildon, where hardware supplies were needed for the construction of Eildon Weir.

Our family then lived through the Great Depression of the thirties, formative years for our parents who were by then at school. Our father was boarding at Xavier College and our mother was at Croydon Primary School. By the end of the decade the world was at war again.

During the war in a munitions factory, in Maribyrnong, two very different family histories were to merge into one. One was Irish Catholic, successful and quite wealthy, and the other was staunchly Protestant and relatively poor. One was involved in the Melbourne horse racing scene and the other was teetotal and interested in ideas and the new ‘isms’ that were emerging on the other side of the world. Our parents were married at the end of World War 2.

1950s

Our mother’s view of the 1950s, in her recording, is of a time of burgeoning economic growth and development. To us, it is the decade we first became aware of the world.

Our world was redolent with Australiana, but we were intensely aware of our British heritage, and it dominated our reading, our schooling, our whole culture. A portrait of The Queen hung in our school. Sue remembers keeping a scrap book at home of magazine articles about the Royal Family. She was particularly interested in the corgis. Apparently I had one too, and it contained very many pieces about Princess Margaret.

Enid Blyton Books:

Globally, it was a dangerous world, with the cold war in full swing, and a very real threat of nuclear war. Our parents had quite well developed political opinions, particularly our mother, so we were exposed to adult conversations about the issues of the day. Family friends and neighbours, the Lees, were active in the union movement. They encouraged our parents’ involvement in the movement for “unilateral disarmament” and other left wing activities. I remember our mother’s admiration for an older couple who took a small boat out into the Pacific Ocean to protest the nuclear testing. Bikini Atoll in the Pacific, sixty years on, is still a no go zone from the USA nuclear tests carried out there up until 1958.

This was the time of McCarthyism in America, and Australian political attempts to ban the Australian Communist Party: a divisive time, where everyday people had strong opinions one way or the other. Sue remembers Prime Minister Menzies as “the devil incarnate”.

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament became overwhelmed in the 1960s by anti Vietnam War action, but it was an important political movement of the 1950s. The familiar “Ban the Bomb”, or “Peace” symbol was invented in 1958, as a symbolic representation of ND (Nuclear Disarmament)

Our family was, by today’s standards, quite poor, but this did not impinge on our life, at this time. We were well fed, we had a stay at home mother who looked after us and the struggle to pay bills was not part of our conscious experience. As far as we children knew, we were neither poorer nor better off than our neighbours, with the exception of the family in the housing commission house nearby, whose son had polio and who didn’t always have enough to eat. The world, as we observed it in our daily life, was largely classless. Perhaps Australia at this time really was the egalitarian workers’ paradise it purported to be, to prospective migrants in Britain. (only whites of course)

Nevertheless, we knew about the religious and economic differences within our family: that our father’s relatives were wealthy and that we were not, because our parents’ union was a “mixed marriage” and very disapproved of. We were very aware of their Catholicism and our Protestantism, and that we were not as close to our grandmother as our cousins were.

Our father during the 1950s, went from working as an industrial chemist by day, and studying by night, to full time teaching. We got our first car, a television and a refrigerator. By the end of the decade there had been four children born. It was busy, but simple life, encumbered by very little “stuff”.

Our suburb of Box Hill South was the edge of suburbia, when our parents first bought their block. During the fifties the new suburbs filled in with more and more families, and the frontier stretched east towards the orchards of Blackburn.

Below is Doncaster, contrasting the 1945 view to that of today. It was little changed in the 1950s. We remember breaking an axle on our Talbot car in Doncaster, a farming and orchards area with narrow unmade roads.

The sewerage reached us during the late fifties. Neighbours got together to dig each others’ trenches. The footpaths were paved, allowing us to roller-skate along them.

The streets were deemed to be safe enough for five year old girls to walk unsupervised, from Box Hill South to Surrey Hills to Sunday School and to Bennettswood to school.

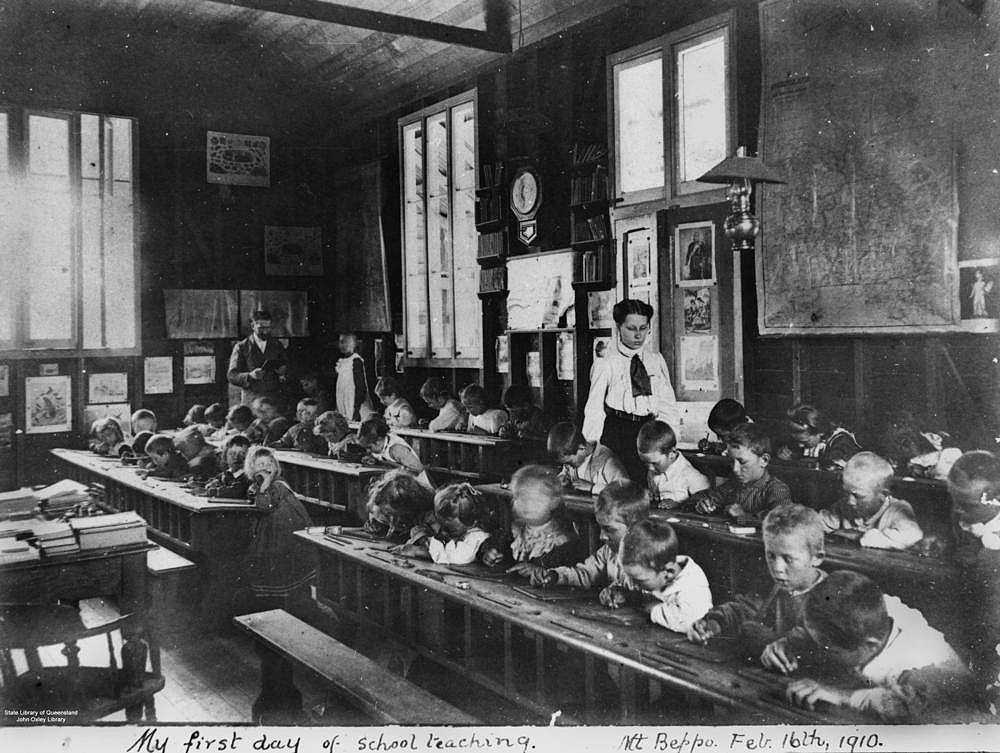

We are baby boomers, and this was the most booming time. When we began school, Sue in 1954 and me in 1957, “temporary” schools were being thrown up, and unqualified teachers recruited to deal with the rush.

My first experience of school was a few weeks in “bubs”, and then the-bursting-at-the-seams class was reduced by a handful of us being put straight into Grade 1. Here is that grade photo with Miss Meadows and her 47 pupils.

1960s

This decade covers our teenage years. It was a time of huge change in the western world. By the end of the decade, Neil Armstrong had walked on the moon, women were controlling their own fertility with the Pill and popular culture had discovered the huge Baby Boomer teens market. During the sixties, there was a general loosening and questioning of traditional social norms. Older people were probably more aware of these momentous changes. For us the loosening of the cultural apron strings, that is such a feature of these times, coincided with the loosening of our familial apron strings.

The conflict between our generation’s straining at the bit and society’s entrenched traditional values played out in our school life. As fashion hemlines rose, school uniform strictures fought them. We knelt to have the gap between our uniforms and the floor measured precisely, and hastily pulled down our hoiked up dresses whenever a teacher came in sight. The anti war slogans on our pencil cases, alongside the names of pop groups we fancied, had to be kept hidden, or there would be detention. A new rule dividing the grassed hill area into a boys’ side and a girls’ side transformed the hill into a vast empty space with a cramped central area where everybody sat alongside the invisible line. In our school, as far as we can remember, there were no brown faces, hardly any Asian faces and no Aborigines. Foreigners were the Italian and Greek “new Australians”, and even they were rare in our (then) outer Eastern suburb.

Culturally, as more and more families spent more and more time around the television set, American culture rather than English, began to dominate our life.

We can’t remember exactly when we got a television set, just that it was bought specifically for watching cricket. As a family we watched the Australian serial Bellbird, which preceded the seven o'clock news. There were a succession of American sit coms we all watched, like My Favourite Martian, Bewitched, Father Knows Best, the Donna Reed show, Bachelor Father, My Three Sons and Mr Ed. After school I remember Clutch Cargo, Sea Hunt, George Reeves in Superman, and Hogan’s Heroes, F troop and Bonanza. And very rarely we were granted permission to watch 77 Sunset Strip. These are nearly all American titles. There were Australian and English shows too, but it is the American ones we remember.

With this American influence in our lives, and increasing prosperity, “teenagers”, a term first heard in the 1950s, emerged even more as a marketing target. For the first time, teenagers had their own music, fashion, language. I was more plugged into Teen culture than Sue. I began to go to local Saturday night church dances from about aged 14. There was always a live band who played rock and roll covers. A group of us from church would go.

Dress was quite formal, ties for boys and stockings and heels for girls. I remember the winter that plain coloured wool dresses with white crocheted collars and cuffs were all the rage: probably 1965. Auntie Bert, dressmaker to the wealthy ladies of Melbourne, made me a tailored aqua one with little kick pleats around the bottom.

Below is fourteen year old Margaret in the aqua wooden dress with while crocheted collar and cuffs.

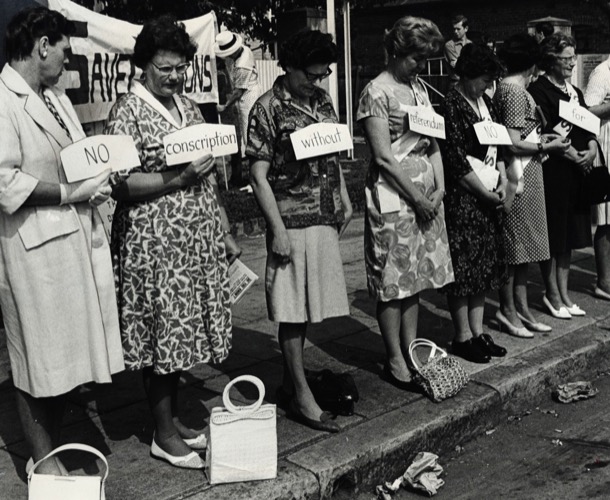

During the 1960s, Australians were entrenched in the divisive Vietnam war. Our family was by default anti war, and the “all the way with LBJ” policy of our government was fiercely criticised. In 1967, my boyfriend and another close family friend was conscripted for military service. Against huge opposition, the government had voted to call up into military service some twenty year old men. Many of them ended up fighting in the jungles of Vietnam. Our mother testified in court for the other friend, who was a registered conscientious objector. But many other friends and acquaintances went off to Vietnam with their hair shaved and very basic training. Some of those veterans live with the trauma of those experiences even today.

A "Save Our Sons" movement protested against conscription:

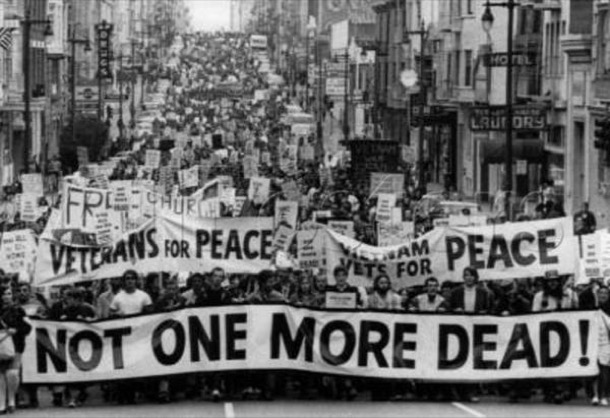

Gradually, public opinion in Australia, as in America, swung firmly against the war; and ordinary Australians demonstrated in the street.

By 1970, Sue and I had left school and were engaged in our tertiary studies, sharing a house in North Balwyn. University was still expensive, and we both managed it by gaining a bonded scholarship called a Studentship, which paid our fees, as well as a small living allowance. Even in a relatively enlightened family like ours, it was made clear that any family budget that was to be spent on university studies, was to be saved for our younger brothers, because they were boys.

1970s

The 1970s was a decade of change for us personally, and a tumultuous time worldwide. In some ways, the decade was a continuation of the 1960s. Women, gays and lesbians and other marginalised people continued their fight for equality, and many Australians joined the world wide protest against the ongoing war in Vietnam. Outrage at the continuing conflict was fuelled by the graphic coverage of the brutality of war, available nightly on our TV screens.

Protest was bitter and violent.

By 1975 Saigon had fallen: a humiliating defeat for the USA.

There was more violence as Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge murdered 1.7 million Cambodians, and on the other side of the world, the IRA fought for British withdrawal from Northern Ireland.

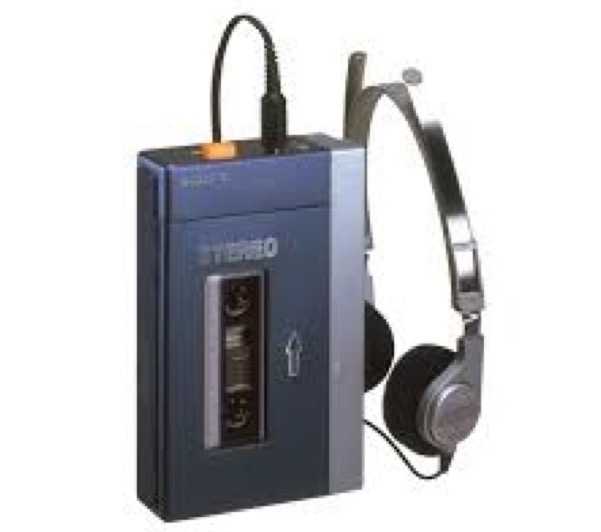

Rapid advances in technology were in play, changing our world and planting the seeds for the creation of digital world, we are grappling with today. Apple launched the Apple 1, a desk top computer, pocket calculators were commercially available for the first time, and music became mobile with the release of the Sony Walkman.

In the popular music scene, Elvis Presley died, the Beatles split up, the Sex Pistols band recorded an album and disco music took the world by storm.

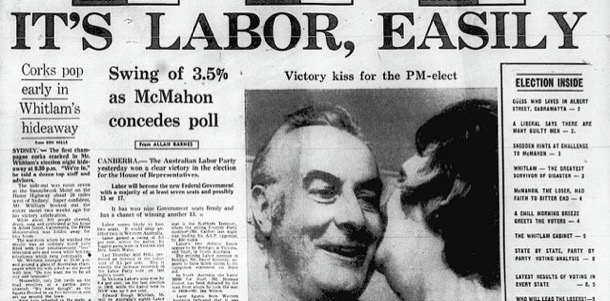

In Australia, at the beginning of the decade, Gough Whitlam led the Labour Party to victory in the 1972 election. This ended twenty-three years of unbroken Liberal-Country Party Coalition government.

Change was inevitable and rapid: the troops were brought home from Vietnam; educational reforms were introduced, such as free University education; and Whitlam visited the feared red menace, Communist China. Inept financial management, scandal and the rate of change contributed to another landmark event now known as, The Dismissal. Whitlam was sacked by Kerr, then Governor General.

Gough Whitlam stood on the steps of Parliament House and declared “Well may we say ‘God save the Queen’, because nothing will save the Governor- General”:

The Liberals returned to power under Malcolm Fraser. For Labour supporters like us, it was a bitter pill.

Waiting in the wings was Bob Hawke, who was both President of the ACTU and President of the Labour Party. The 1970s ended with Hawke deciding to enter politics. He was elected as the member for Wills in the 1980 election and Labour was once again in power. The 1980s in Australia was Hawke’s and Paul Keating’s decade. The reforms they ushered in changed the face of Australia: we thought for the better.

At the beginning of this tumultuous decade Margaret and I were fancy free. We moved out of home, sharing a house and living on our teaching studentships, as university education was not yet free. Margaret supplemented her income, paid $1 an hour, working at the first fast food outlet in Bourke Street. Working the late shift posed no danger as the Derby closed about 11 pm [very late] and Margaret was able to walk out to her Morris Minor parked right outside the restaurant. “It was always easy to park in Bourke Street, there were lots of parking spots,” remembers Margaret. It was such a different city then. We also embarked on our teaching careers. I began my teaching career in Sale and Margaret at Moe.

We had wonderful camping holidays, often in the Snowy Mountains; we saw interesting alternative movies at the Walhalla picture theatre in Richmond; we went to Sydney on the train to see Hair and saw nudity on stage; so risque! We listened to the Beatles, The Seekers, Cat Stevens and Peter Paul and Mary amongst others, on vinyl of course.

Margaret had begun teaching at Moe in 1973 and Jono and I, after a year overseas, both taught at Drouin High School, quite nearby. By the end of the decade, I had given up teaching and was at home at Gowar Avenue with a three year old Anna. Margaret was teaching at Croydon and was living in Gully Crescent with Ken.

Conclusion.

Marge and Alice finished their oral family history with their weddings and the end of the Second World War. It was neat: 1850-1950. It left off when they were both about thirty, settled into the business of raising children.

We are finishing our own overview at the corresponding stage. For us, this is 1980.

In the very last minute of the recording Alice, by herself for this part of the process, reflects on the speed of technological change that she and Marge had witnessed in their lifetime.

“But there’s a sort of corresponding suddenness in those new technologies and we tremble, as we think you do too, at what the outcome of all this is going to be for your children.

So looking back over that hundred years, we see this period of rapid, strong and significant development: a development that began gently enough, but now, in 1990, is rushed and killing and devastating.

And we look forward into the future for you and for our grandchildren as a time where perhaps you will learn what de-development is all about, and maybe the graph is going to go gently and firmly and calmly for you, into a period that is not as frantic as the one we’ve lived in.”

Strikingly and shockingly, the suddenness and the devastation she speaks of in 1990 has not diminished, but increased. And now, in 2018, as we watch our own grandchildren navigating their way into the world, we too tremble at what the outcome of “all this” will be.

A Great Sorrow

Our mother's sister, Marge, who had been close to marrying an American Serviceman during the war, had had a whirlwind romance with George Rostos, a Hungarian Jew, who had emigrated to Australia during the war. His parents, who were later to join him and Marge in Australia, had been in a Nazi concentration camp. George and Marge were married in 1945, the year the war ended.

From left: Alice, George and Marge

Jim and Alice, our parents, were married later the same year. A busy year, as in October of that same year, George was offered a job in Sydney at the CSIRO. It was an exciting and welcome offer but it led to “a great family sorrow” as George and Marge moved to Sydney. They travelled to their new life on The Spirit of Progress, then a steam train.

The family gathering the night before. From left: George, Alice, Freda, Alf, Auntie Bert and Marge.

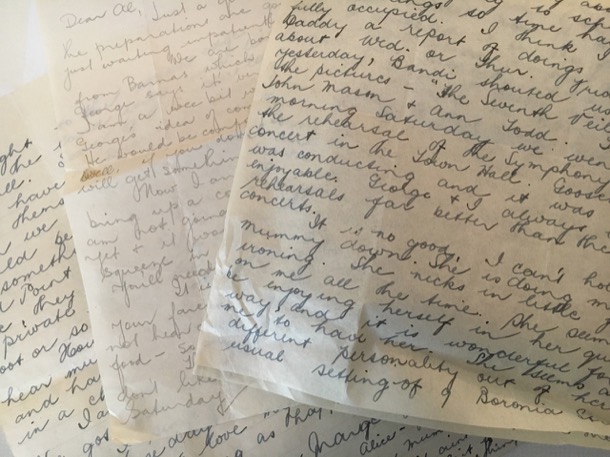

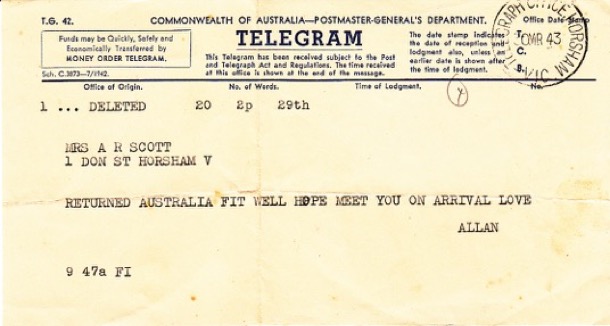

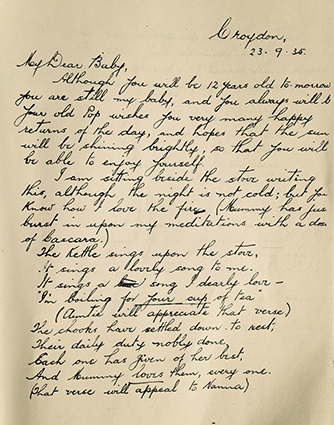

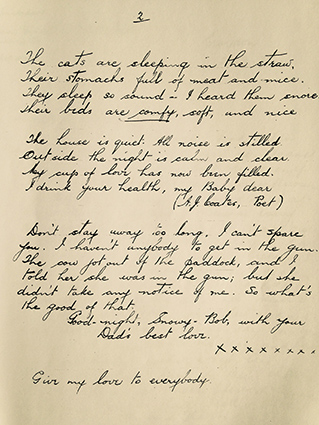

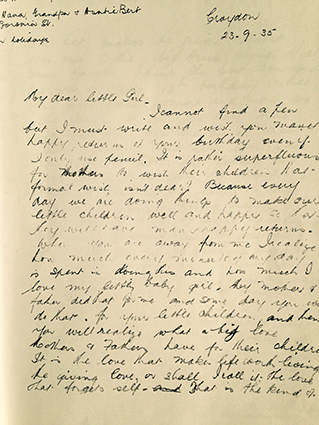

To us in the world of instant communication and Skype we may think, “What’s all the fuss about, it’s only Sydney?” But, in1945, five months after World War 2 ended, it was quite a different matter. During the war people had not travelled much, and even long distance train fares were expensive and airfares, prohibitive. Once the train pulled out of the station one of the few means of communication was by letter:

The only other means of communication was by telegram. Telegrams were expensive, as you paid per word, and therefore they were usually only used in emergency. You would take the message to the post office where it was translated into Morse Code, and then transmitted along telegraph wires, decoded at the other end and delivered to your home by the telegram boy on his bicycle.

LIFE IN SYDNEY

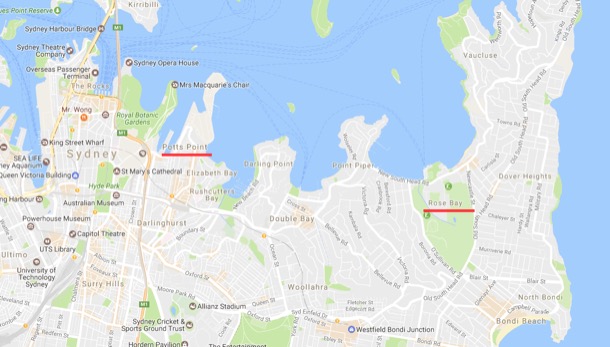

And so began their new life in Sydney. The first three places from 1945 to 1949 were all in fashionable, post-war, cosmopolitan Sydney.

Marge and George had only known each about a year when they moved to Sydney. Marge speaks of their friendship group in Sydney, including Bandi, with whom they lived, as Hungarian Jewish refugees. What an amazing new world she lived in! Rose Bay and Potts Point were, and still are, in the heart of fashionable Sydney.

Marge speaks of watching the flying boats landing at Rose Bay. It had been a busy “airport” during the war, and, in 1945, was still used for overseas travel.

POTTS POINT

Their exciting new life continued in another inner city apartment.

Potts Point is right on the harbour.

BELLEVUE HILL

Bellevue Hill, where Marge and George lived for three years from 1947, is in much the same area of Sydney.

They shared this flat with Phyllis, who seems to have worked in a job where she had access to otherwise unobtainable items. Marge speaks of her often in her letters.

These two extracts are from letters Marge wrote to Alice from Bellevue Hill, in 1947:

We, George, Phyllis and I, went to the beach (Tamarama) yesterday. Phyllis got let down by one of her blokes whom she had quite a crush on and she came with us. I must admit she took it with great dignity and amusement, though I know she was a bit crushed. So we sunned from 11 o'clock till 3. George and Phyll went nicely pink, but I did not change from my pale putty.

The job is still quite within my scope. i mean the two jobs. Phyllis helps a lot and, even if she is not home for dinner, never neglects to make us a delicious sweet from her American Cookery Book and peel some veggies for me.

She helps in many small ways which are not noticeable too, and I often go to do a small job to find it is already done. She brings lots of things from the planes - fruit and soap and face tissues; and brings me Persil (laundry powder) and Lux (toilet soap) and Velvet Soap (used for washing dishes, floors, surfaces, hand washing clothes etc), which have been unobtainable here for months.

This one was written acknowledging a birthday present:

I am so terribly thrilled with the cloth. When i first opened it I thought you must have got cloth at some art shop with stamped design and spoked hem and advised colours, but on reading your letter I find it is all a family affair and I am truly amazed and pleased with your taste and industry. Did you really do that spoked edge all on your own? I just love the colours, especially as my favourite colour is yellow. Thank you darling so very much. I shall cherish it and wash it so carefully and it will only be used on very special occasions. Tait also gave me a cloth - a beige one, very tasteful and good material. She also gave me a coffee pot to go with my set. Stephen left me a beautiful round cloth in Hungarian lace too, so i am not so badly off now. Phyll bought me a butter knife, a rolling pin and a beautiful round crystal bowl with two little handles and that engraved work around the sides- grape design and I love using it. I am now serving up my meals continental fashion these days, piling everything on dishes in pretty patterns and let the folks serve themselves. - It’s fun…..

…….if George were Australian I would certainly encourage him to take a job in Melbourne, but good jobs for foreigners don’t grow on gooseberry bushes. Here is an example: Last week Knox Schlapp advertised for a clerk. Several people called and one among them with a German name. I announced him to Mr Shaw who said to me, “That’s a foreign name. Is he a foreigner? I don’t want to see him.” I had to go and tell the chap to go away, and he had by far the most intelligent face of all that we interviewed. (Mr Shaw doesn’t know that George is a foreigner) They are turned down before even given the chance. Then again, George is not treated as a foreigner out there (CSIRO). In the atmosphere of prize scientific research, which exists there, such things do not matter and he is gaining the confidence and poise which he certainly would not out in the industry and commercial field.

SEVEN HILLS

Life was to change dramatically for Marge and George when they moved out of fashionable, lively Sydney into a house in a newly developed housing estate at Seven Hills, 37 kilometres west of the city.

Seven Hills Estate in 1945.

It was not until the mid 1950s that George finally got a job in Melbourne CSRIO, and they all moved back to live close to their family.

The Demon Drink

It was clearly uncommon for anyone in our narrow anglo world to drink at home. Here, for instance, is an extract from a Primary school resource book on Temperance from the 1950s.

The international Temperance movement was one of the most powerful social movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Its advocates regarded alcohol as a social evil and sought to have it banned entirely, or at least its consumption drastically reduced.

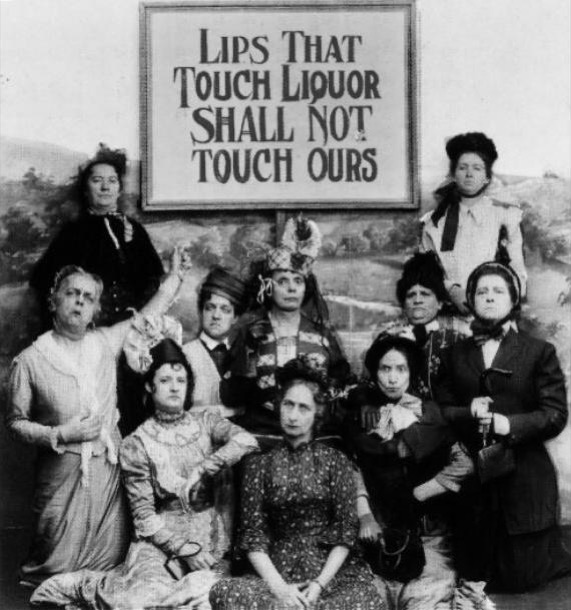

Initially it was just a move against drinking spirits and “hard liquor". But during Victorian times it became more a push for total abstinence and became more specifically a women’s movement, connected with Protestant Christianity. Groups of women activists were to be found right across the western world.

The Temperance movement had its most obvious success in America, where the sale of alcohol became illegal across the whole country overnight in 1920.

This period of American history has become known as ‘Prohibition”, the Roaring Twenties. It conjures up images of gangsters, speak easies and moonshine. The law did not have the support of much of the population. But it wasn’t until 1933 that it was finally repealed.

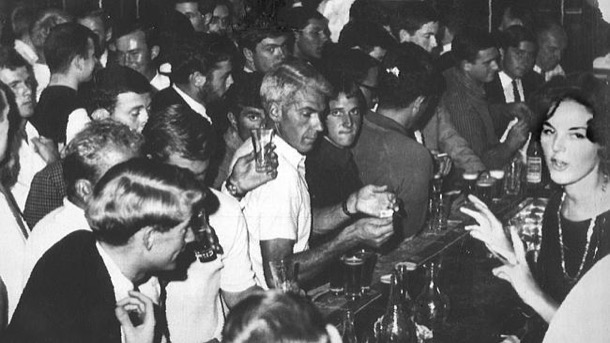

In Australia the temperance movement did not succeed in having the ‘demon drink’ banned but it did lobby vigorously for restriction of hotel opening hours. By 1923, hotel opening hours were restricted in all states. The closing of hotels at 6.00 PM led to a phenomenon known as the ‘Six O’clock Swill’.

It is hard to believe looking back that the daily rush to the bar was part of everyday life. Rather than limit drunkenness it actually encouraged it, as men who ‘knocked off’ work at 5 o’clock had only on hour in which to drink. Hotels were set up to serve as many beers as were demanded in this hour. Pubs were overcrowded, as men five or six deep lined the bar waiting to be served and patrons spilled out into the streets.

Pubs did smell strongly of beer as so much was served in such a short time. Sue can remember walking past Young and Jacksons on her way home and pushing her way through the throng of men, spilling out onto the pavement on the corner of Flinders Street and Swanston Street. Men, yes only men! Women were not permitted in the Bar until the early 1960s and for many years after that it was frowned upon. We can remember conversation stopping momentarily when we first walked into a bar particularly in the country.

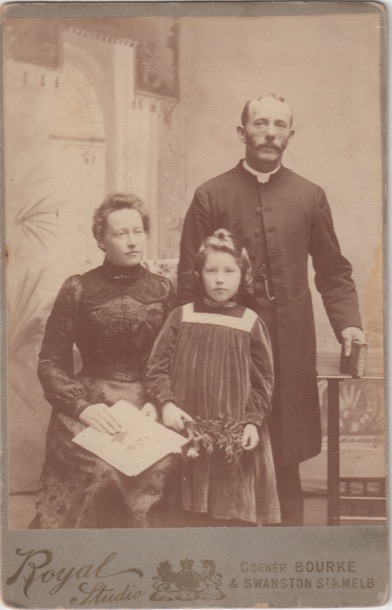

The Demon Drink indeed! We come from a long line of teetotallers: our great grandfather Reverent Alfred Coates, our great aunt Sister Bessie, our maternal grandparents, Alfred and Alfreda, their siblings and our parents. Our mother’s family, the Coates, being staunchly Methodist, we imagine would have been very sympathetic to the temperance agenda. Here is Alfred, in his Methodist pastor uniform with Emma and their daughter:

We were very aware as children that none of our family touched alcohol and that particularly frowned on by our rather upright Grandfather.

We too, at the tender age of eleven of twelve, have had our brush with The Independent Order of Rechabites, who provide educational material for Victorian Schools.

Alice and Marge as old ladies recounted their childhood memories of drunkenness, in the country town of Croydon during the 1930s, with obvious disapproval and distaste. Here they discuss the public drunkenness they witnessed at the hotel and wine hall near their house:

I remember our aunt having a glass of beer at the dinner table, when we were staying there as children. I commented on it and I remember being rebuked. Later our mother told me that it was medicinal, that she had found that drinking beer with food helped her digestion. That mum had felt the need to explain it that way, and that our aunt had reacted so strongly to a child’s interest is understandable in the light of heir own childhood experiences and family attitudes.

And then, during our late teens, as the 1960s became the 1970s, this part of our past just melted away. It became normal and natural too open a bottle of wine to share. There was binge drinking around us, especially at Uni parties, and the drink driving hazard was evident, but the moral dimension, the “holier than thou” attitudes, the raised eyebrow were all gone. Society had grown up about the same time that we did.

.

War Service

Our family stories research has led to the discovery of four great great uncles: four brothers who were soldiers. They were four of the seventeen children of Martha and Joachim of Heather Farm in Wandong, about whom we wrote in "The Poor Little Thing" on June 8th, 2016 and "Heather Farm" on August 3rd, 2016. Our maternal grandfather Alf, was their nephew.

Learning their stories, imagining their experiences, fitting their details into the wider sweeps of military history has been enthralling and rewarding.

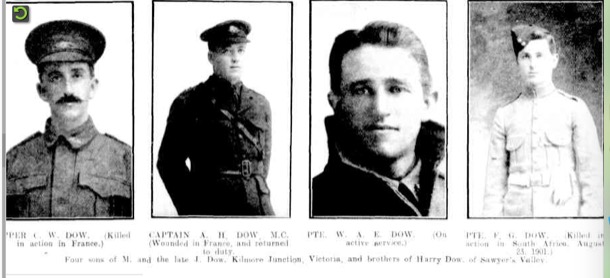

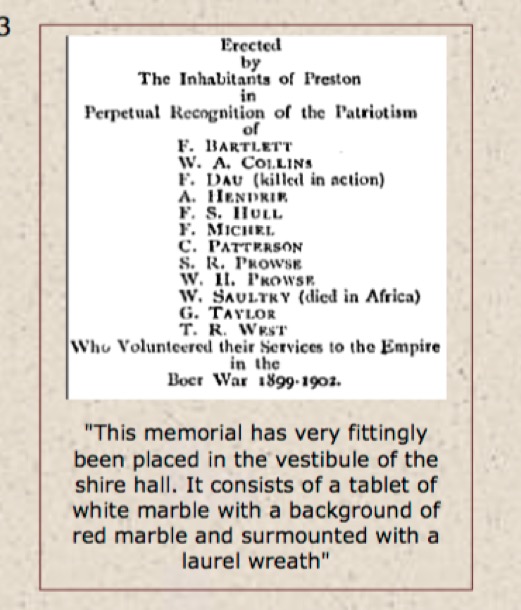

We present the four Dau (Dow) brothers, Frederick, Arthur, Charles and Walter.

Frederick and Arthur actually enlisted as Dow, an anglicised version of Dau. It is a constant confusion.

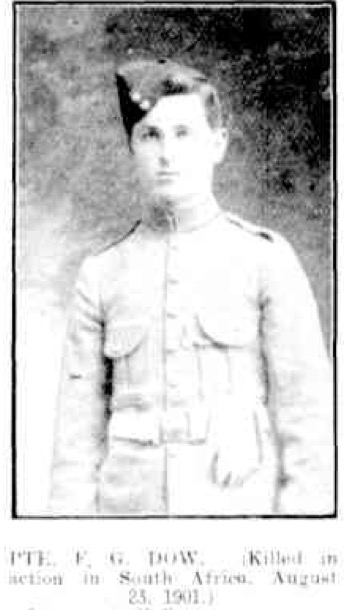

PRIVATE F. G. DOW

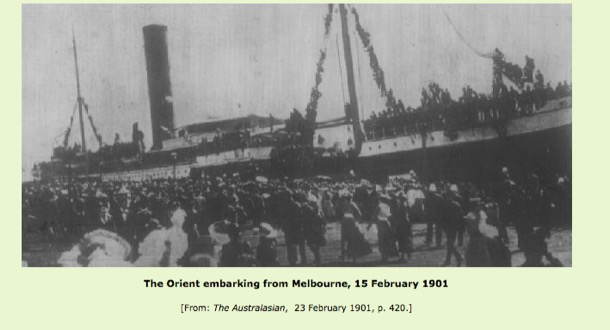

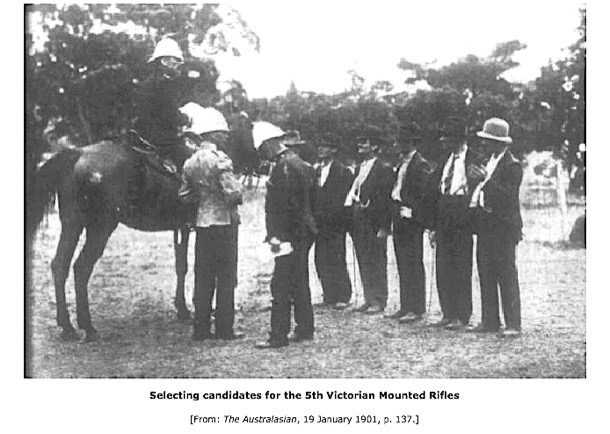

Australia was twenty-eight days old when nineteen year old Frederick sailed on The Orient out of Melbourne, bound for South Africa and the Boer War. His company was the Fifth Victorian Mounted Rifles.

Britain had colonised the southern part of South Africa eighty years earlier and had had an uneasy relationship with the other colonisers of this area, the Dutch Boers, who had been there for a hundred and fifty years longer. Tensions had escalated to war in 1899, and the British Empire was required to send troops to participate.

By 1901, the war had become a drawn out guerrilla affair mostly in the desert-like Transvaal area with small groups of Boer soldiers attacking and then disappearing back into the harsh dry landscape.

Many of the “colonial” troops, like Frederick were bushmen, tough, self reliant and skilled at shooting from horseback: exactly the set of skills needed for this type of warfare. But it was very hard on men and horses alike. Most of the fighting took the form of small skirmishes, but sometimes the men had to attack remote farmhouses, confiscate the livestock, destroy the farms and escort the women and children to the notorious concentration camps where thousands died. R G Keys of South Moorabbin wrote of making captures of large numbers of prisoners and cattle and having brought in large numbers of Boer families. “We have also burnt thousands of acres of grass and a number of farms and have destroyed everything of any use to the Boers.”

They spent long periods in the saddle with few opportunities to bathe or change their clothes; lice were a constant problem. Temperatures on the veld ranged from relentless heat during the day to freezing cold at night.

Private F W Collins wrote, “What I can see of the war is that the Boers can keep it on as long as they like, the only way is to starve them out. They get right in the mountains, and there are bullets whizzing about you and you cannot see any enemy. We are going from daylight till dark, up at 4 o’clock in the morning, and it is sometimes midnight before we get in again, so you can imagine we feel quite knocked out. When I get back to old Victoria I’ll do nothing but sleep.”

We don’t have much detail about Frederick’s death, but Lord Kitchener, Field Marshall in charge of the war, reported in one of his dispatches: "on the 23rd August Lieutenant Colonel Pulteney had a sharp engagement with the enemy on the west side of the Schurveberg, in which the Victorian MR (Mounted Rifles) had 2 men killed and 5 wounded.” One of those two men killed was Frederick Dow.

Two years later, his mother, Martha, and brother Harry inserted this memorial in the local paper:

In loving memory of dear Fred, who was killed in battle near Vryheld, South Africa, August 23, 1901; aged 19 years and 6 months.

Tis two sad years ago today,

The trial was hard, the shock severe,

To part with one we loved so dear.

He is gone, but not forgotten,

Never shall his memory fade;

Sweetest thought shall ever linger

Round about our soldier’s grave.

MAJOR A. H. DOW

Arthur was on one of the first ships to leave Melbourne for the war. He sailed from Station Pier Melbourne on the Orvieto on October 21st 1914. There were huge crowds to wave off this first wave of volunteers.

Soldiers from the Orvieto disembarking at Egypt:

Arthur was a career soldier. He had joined up as a military engineer, aged seventeen in 1908 and had already been promoted to Warrant Officer.

Like all of those first soldiers, after a short time in Egypt, Arthur was dispatched as part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force to what would become known as Anzac Cove, Gallipoli. He was there for the very first Anzac Day landing, but went ashore “several days” later. He must have watched from his ship as the first few waves of shore boats struggled amid Turkish bullets and shells that rained down from the cliffs. By the time it was his turn, things were still very chaotic and dangerous. It took ten days for the troops to be safely dug in.

On June 16th, he was Injured and was treated at the hospital on the Greek island of Lemnos.

He went back to Gallipoli ten days later.

At the beginning of August, Arthur was detached for duty to Assistant Adjutant General 3rd Echelon in Alexandria (which dealt wth military discipline, though he was in the “records section&rdquo![]() .

.

By March 1916 he was with the Fourth division engineers at the huge Anzac training area near Cairo, called Tel-el-Kebir, a six mile long “tent city”, where he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant.

He must have participated in the notorious three day march across the desert in searing heat to Serapeum, on the Suez Canal.

Here there was more training, in preparation for the move to France, and he was promoted again to Lieutenant. On June 2nd, he travelled on the ship “Kinsfaun Castle” to Marseilles, in the south of France.

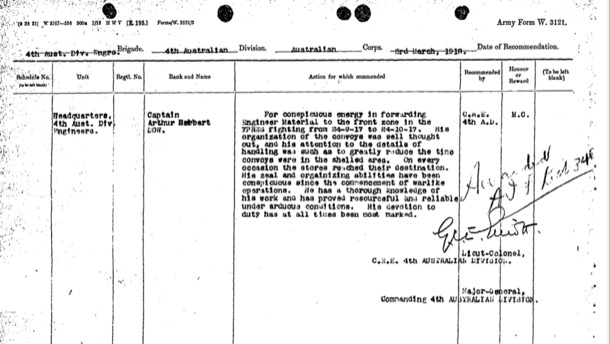

The next mention in Arthur’s record is six months later, in January 1917, where he is “mentioned in despatches” (a sort of honour) and then again on June 26th, where he is promoted to Captain.

We know what he was involved in during those couple of years in France and Belgium because we know what unit he was in.

He fought at Ypres and Messines Ridge and Passchendael: all infamous places in the history of the first world war.

It was for his work from 24th September through to 24th October that he was awarded the Military Cross.

Arthur was a military engineer. Engineers, also known as sappers, were essential to the running of the war. Without them, other branches of the Allied Forces would have found it difficult to cross the muddy and shell-ravaged ground of the Western Front. Their responsibilities included constructing the lines of defence, temporary bridges, tunnels and trenches, observation posts, roads, railways, communication lines, buildings of all kinds, showers and bathing facilities, and other material and mechanical solutions to the problems associated with fighting.

At the time Arthur won the Military Cross, the 4th Division was involved in the battle of Polygon Wood and then the third battle of Ypres, Passchendaele. It is from the Ypres-Passchendaele area that we get the iconic images we have of trench warfare in a landscape of deep mud and water filled shell holes with broken off toothpick trees, stretching away into a hazy distance; where falling off the duck board paths meant drowning in mud. By the time Passchendael was captured in November 1917, the Australians had fought for eight weeks and suffered over 38 thousand casualties.

At the beginning of December Arthur had a fortnight’s leave in Nice, Italy and on his return he was sent to England to Brightlingsea to train engineers. It must have been a welcome break, but he was back in France by May, 1918.

He was wounded in action on August 8th. At that time his company, the 14th Field Company Engineers was laying wire barriers across the area to be advanced upon in front of the village of Villers Brettoneux. They were harassed by constant German shellfire, and snipers.

The resulting battle was called the Battle for Amiens, and was a resounding success, although between August 7th and 14th, the Australians lost six and a half thousand men.

Arthur left for Australia on September 27th, and within six weeks the war was over.

He remained in the services for a few years. In 1920 he had a few months’ successful treatment for “depression and irritability”. On his application form, where he had to provide supporting evidence for his entitlement to this help, he wrote a single word: “Anzac”.

By 1940, one year into the second world war, Arthur, who had been working in a Government desk job in the civil service, rejoined the army as a Major. He was 49, married with two children, and living in St Kilda.

His war this time, was fought at a desk, sometimes in the Middle East and sometimes back in Australia. His war record mentions positions like “Hiring and Claims”, “Accomodation and Quartering”. He left finally in October 1945, aged 54. During this time he had treatment for an affected patch of skin in his mouth. The doctor mentions that this is the spot where Arthur’s pipe customarily sits.

The last mention of Arthur in the war record is application for repatriation consideration for a minor health issue. He was a healthy 72 and living in Boronia.

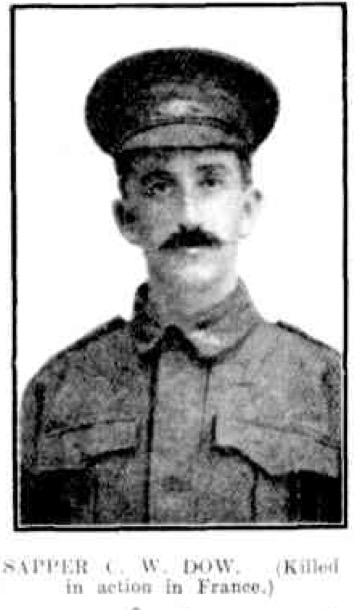

SAPPER C.W. DAU (DOW)

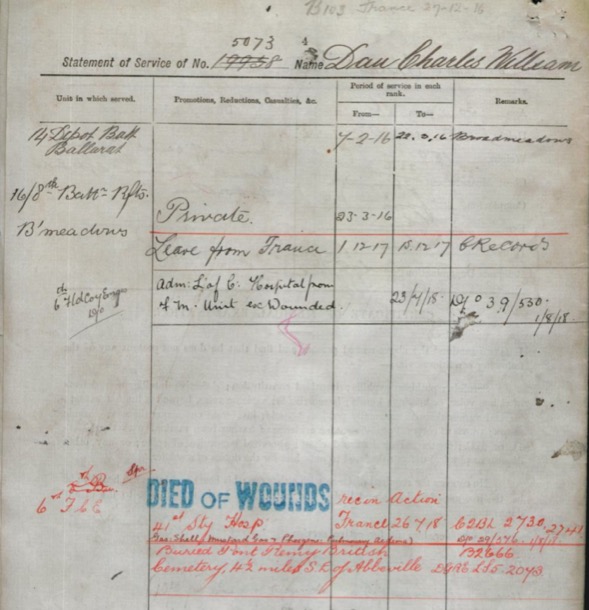

Like his brother Arthur, Charles enlisted as a sapper, or military engineer. He joined up in February 1916 in Hamilton, where he had been working as a railway “ganger”. He was thirty, slim, fair haired and blue eyed and was married to Edith, who was still back in Wandong with their three children.

He left for Europe in April and by October had joined the Second Division in Belgium, before marching to the Somme area in France. His division was involved in attacks on a collection of German trenches known as The Maze,

The main Somme fighting came to an end on 18 November in the rain, mud, and slush of the oncoming winter.

Over the next months, winter trench duty with its shelling and raids became almost unendurable and only improved a bit when the mud froze hard. The wet and the cold made life wretched. Respiratory diseases, “trench foot” – caused by prolonged standing in water – rheumatism and frost-bite were common. Many survivors would later say that this was the worst period of the war and that their spirits were never lower. Large-scale fighting did not resume until early 1917 when spring approached and a German offensive re-took areas previously heavily fought for.

Charles remained with the sixth field company, second division throughout. By the middle of 1917, they were in action in the mud at Passchendaelle. Charles’ brother Arthur was there too, with a different division. Eight weeks of heavy fighting took a huge toll on Australian troops.

At the end of 1917, he had a three week leave in England, returning to his unit in December, just in time for the German Spring Offensive, aimed at retaking Ypres in Flanders. The second division were involved in Messiness until March and then the battle of Lys in April. In June they participated in the very successful Battle of Hamel.

The Allies finally began to push the Germans back. Charles was involved in the Battle of Amiens and other attacks from the village of Villers-Bretonneux.

Then, on July 23rd, after weeks of very heavy fighting, Charles was affected by a mustard gas shell.

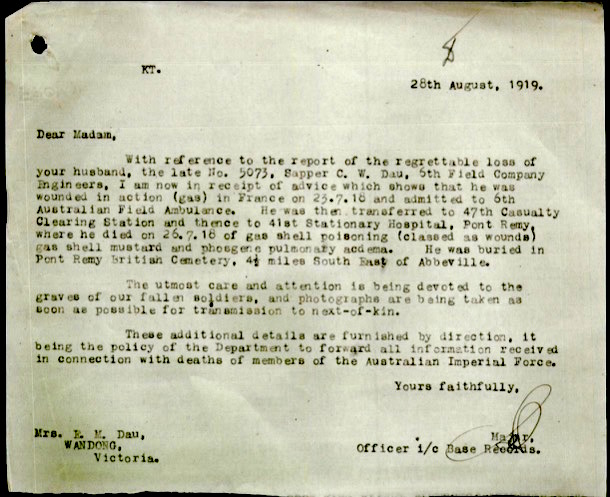

A letter to his wife, Edith, written in August the following year explains the story from here:

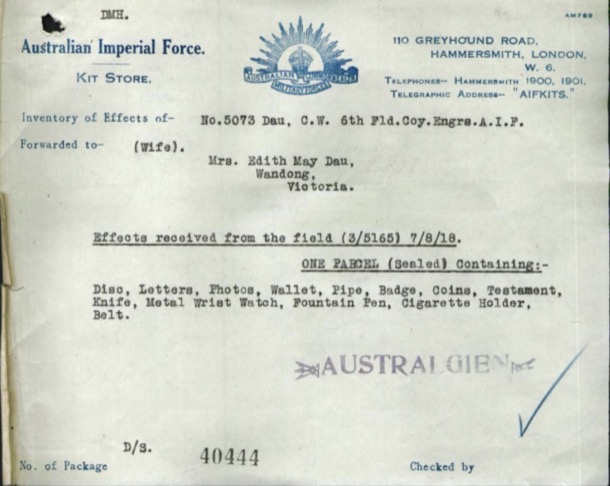

Edith received a parcel containing Charles' last few possessions:

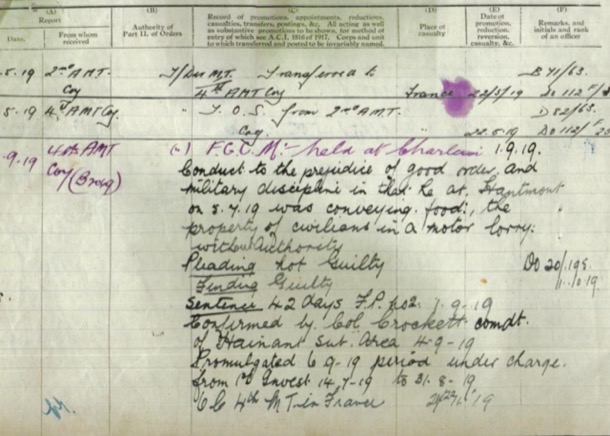

From Charles' military record:

Mustard Gas

Chemical weapons were first used in World War I. They were primarily used to demoralize, injure, and kill soldiers in trenches, against whom the indiscriminate and generally very slow-moving or static nature of gas clouds would be most effective.

Some gases used actually killed soldiers, but mustard gas was more a disabling chemical. On initial exposure, victims didn’t notice much except for an oily or “mustard” smell, and so the first men exposed to this “mustard gas” did not even don their gasmasks. Only after a few hours did exposed skin began to blister, as the vocal cords became raw and the lungs filled with liquid.

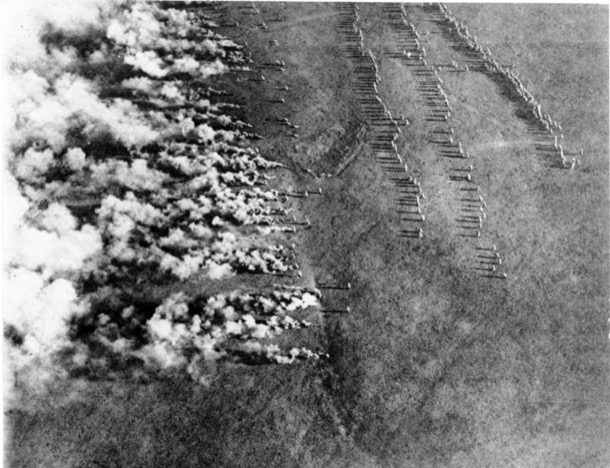

Even if they did have their masks on, they developed terrible blisters all over the body as the gas soaked into their woollen uniforms. Contaminated uniforms had to be stripped off as fast as possible and washed - not exactly easy for men under attack on the front line.