Grace

The Built Environment - Hawthorn

30 07 19 15:36 Filed in: Jim

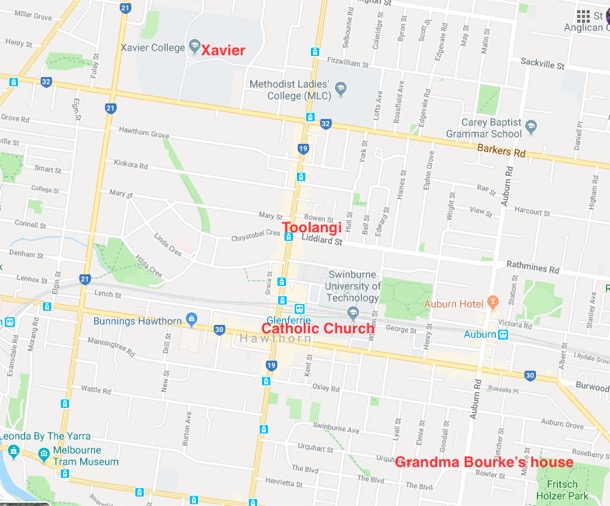

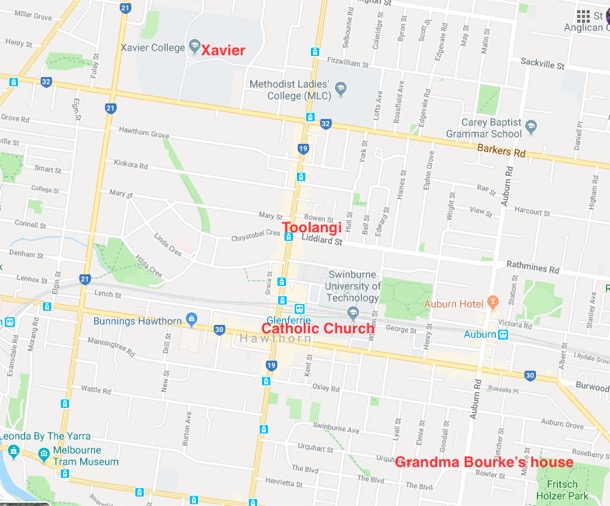

Our forebears have been part Melbourne since the 1850s. They came from Europe, Ireland and Great Britain, arriving at the Port of Melbourne, to make a new life. They found a raw, settlement, recently carved from the Wurundjeri lands: a settlement coping with sewerage, ad hoc development and the pollution of emerging industry along the river. The punt, at Punt Road, provided access across the Yarra that occasionally broke its banks and inundated the new city streets. From this frontier town the newcomers moved out into the country to make their fortunes and raise families. Some of their descendants, our extended family, remain in country Victoria but many, over the generations have made their lives here and left traces in the built environment of Melbourne.

These posts can be viewed as a virtual pilgrimage of the structures and buildings in Melbourne and how they relate to our family. Melbourne is undergoing a tumultuous time of change, as, in 2019, its population grows to nearly five million. Our family landmarks are inevitably caught up in the changes too, as you will see.

Our first post covers the suburb of Hawthorn.

Glenferrie Road

733 Glenferrie Road is listed on the Glenferrie Road Historic walk as the ‘historic mansion Toolangi. It was built in1905 as a doctor's surgery and residence for William Clayton, physician and surgeon.’

This house is significant to our family as two generations of Bourke doctors lived and worked here and our father spent his teenage years here.

It was in the late 1930s that our paternal grandfather Dr. Hugh Bourke and family moved to Glenferrie Road from Koroit. Presumably Grandfather Bourke bought both the property and the medical practice.

At this time, our father was at secondary school at Xavier, where he had boarded until the move. He continued to live in the Glenferrie Road house until he was married in 1945.

After Grandpa Bourke’s death in 1950, Grandma Bourke moved out and Dad’s brother Jack and his family moved into the house. Jack took over the practice, which he ran until he retired.

I have clear memories of the house, both visiting Uncle Jack and, once or twice, the surgery. The house seemed enormous and imposing, and as we mentioned in a previous post, the paraphernalia of Roman Catholicism was very evident. Uncle Jack also had a greenhouse in the back garden where he grew orchids and Christmas Lilies. The garden shed and the greenhouse where still there until recently.

I still associate the perfume of Christmas Lilies with visits to Grandma Bourke at Christmas.

The building next door to Toolangi was the Hawthorn Motor Garage, built in 1912 . From the 1920s the garage was run by Albert James Kane and family, who had it for 20 to 30 years. They introduced the first electric petrol pump in Hawthorn.

The Hawthorn Motor Garage building is on the Victorian Heritage Register. It is the oldest known purpose-built motor garage in Victoria. Dad would have been very familiar with the Kanes and the garage: while courting our mother, he was lucky enough to be able to borrow his father’s car and use his petrol coupons to fill up at the garage next door. As it was wartime, petrol was strictly rationed but doctors received extra coupons, that Dr. Hugh obviously allowed his son to use.

In April 2019, when we visited it, the site of the house and the garage were in the process of being redeveloped. The garden and out buildings have been cleared away but the main structures of the Hawthorn Motor Garage and Toolangi remain. They will be repurposed as part of the new apartment complex being built on this corner.

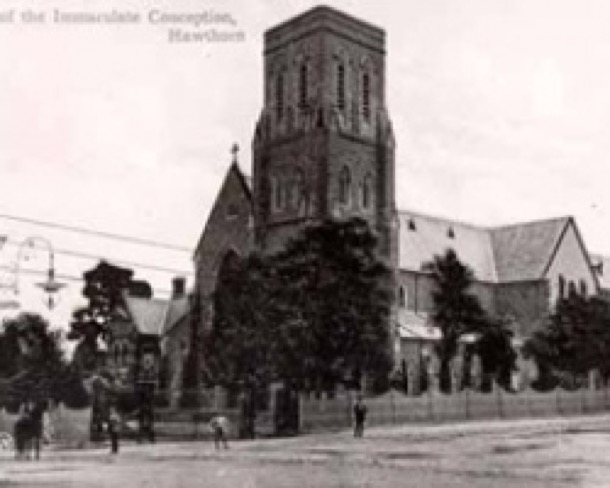

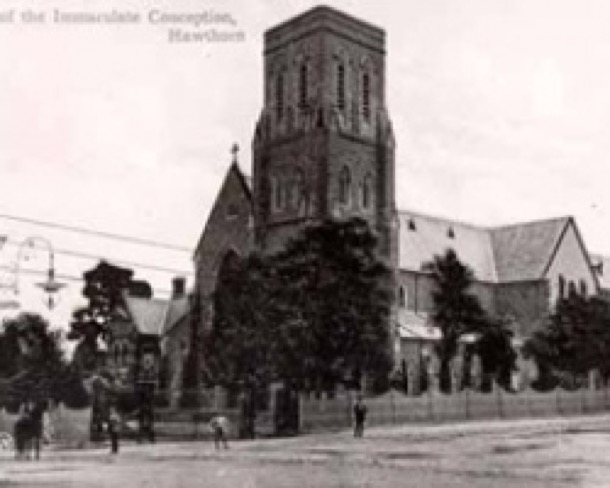

At the other end of Glenferrie Road shops is the Catholic Church. An imposing bluestone structure, the Church of the Immaculate Conception still dominates this busy corner. The Bourke family would have attended Mass here every Sunday. Now I walk past here every six weeks on my way to have my hair cut. Time marches on.

Urquart Street

After our grandfather Hugh’s death in 1950, Grandma Bourke moved a few streets away to Urquhart Street, still in Hawthorn, leaving Jack to bring up his family and run his practice from the Glenferrie Road house.

We remember this house well. Grandma Bourke was a keen gardener whose beautiful roses and bulbs were fertilised by the manure from our parents’ chooks. A huge weeping deciduous tree in the front yard afforded a play area for visiting grandchildren. The house was big enough for our aunt and family, who lived near Warrnambool, to stay over Christmas.

It had a coal cellar, accessed by a trapdoor on the back verandah, with fed the coke heater.

The house looks much the same in 2019, as it did sixty years ago, when Grandma served cake and tea in beautiful china in the front room to her visitors, and mugs of tea with slabs of bread and butter to workmen on the back verandah.

Xavier College

Our uncle and father, first went as borders to Xavier College for their secondary eduction. When our father began there in 1932, Xavier had already been there for fifty years. It was and still is, the premier Catholic Boys private school in Melbourne.

Initially they boarded at the preparatory school, Burke Hall. The buildings of Burke Hall were put together from a trio of mansions on the hill known as Studley Park, some bought by, others bequeathed to, the Jesuits. It first opened, as Xavier College’s junior school in 1921.

Xavier’s senior School is even older. The South Wing is the original building of Xavier College. The foundations date from 1872, the front dates from the opening of the College in 1878, the back half was completed in 1884. It was listed by the National Trust in 1987.

Xavier’s main chapel would have been being built when our father arrived. It was finally completed in 1934. The chapel is a fine building with a huge dome. I have sung in a concert under that dome, and Sue has been in the audience for another concert there.

These posts can be viewed as a virtual pilgrimage of the structures and buildings in Melbourne and how they relate to our family. Melbourne is undergoing a tumultuous time of change, as, in 2019, its population grows to nearly five million. Our family landmarks are inevitably caught up in the changes too, as you will see.

Our first post covers the suburb of Hawthorn.

Glenferrie Road

733 Glenferrie Road is listed on the Glenferrie Road Historic walk as the ‘historic mansion Toolangi. It was built in1905 as a doctor's surgery and residence for William Clayton, physician and surgeon.’

This house is significant to our family as two generations of Bourke doctors lived and worked here and our father spent his teenage years here.

It was in the late 1930s that our paternal grandfather Dr. Hugh Bourke and family moved to Glenferrie Road from Koroit. Presumably Grandfather Bourke bought both the property and the medical practice.

At this time, our father was at secondary school at Xavier, where he had boarded until the move. He continued to live in the Glenferrie Road house until he was married in 1945.

After Grandpa Bourke’s death in 1950, Grandma Bourke moved out and Dad’s brother Jack and his family moved into the house. Jack took over the practice, which he ran until he retired.

I have clear memories of the house, both visiting Uncle Jack and, once or twice, the surgery. The house seemed enormous and imposing, and as we mentioned in a previous post, the paraphernalia of Roman Catholicism was very evident. Uncle Jack also had a greenhouse in the back garden where he grew orchids and Christmas Lilies. The garden shed and the greenhouse where still there until recently.

I still associate the perfume of Christmas Lilies with visits to Grandma Bourke at Christmas.

The building next door to Toolangi was the Hawthorn Motor Garage, built in 1912 . From the 1920s the garage was run by Albert James Kane and family, who had it for 20 to 30 years. They introduced the first electric petrol pump in Hawthorn.

The Hawthorn Motor Garage building is on the Victorian Heritage Register. It is the oldest known purpose-built motor garage in Victoria. Dad would have been very familiar with the Kanes and the garage: while courting our mother, he was lucky enough to be able to borrow his father’s car and use his petrol coupons to fill up at the garage next door. As it was wartime, petrol was strictly rationed but doctors received extra coupons, that Dr. Hugh obviously allowed his son to use.

In April 2019, when we visited it, the site of the house and the garage were in the process of being redeveloped. The garden and out buildings have been cleared away but the main structures of the Hawthorn Motor Garage and Toolangi remain. They will be repurposed as part of the new apartment complex being built on this corner.

At the other end of Glenferrie Road shops is the Catholic Church. An imposing bluestone structure, the Church of the Immaculate Conception still dominates this busy corner. The Bourke family would have attended Mass here every Sunday. Now I walk past here every six weeks on my way to have my hair cut. Time marches on.

Urquart Street

After our grandfather Hugh’s death in 1950, Grandma Bourke moved a few streets away to Urquhart Street, still in Hawthorn, leaving Jack to bring up his family and run his practice from the Glenferrie Road house.

We remember this house well. Grandma Bourke was a keen gardener whose beautiful roses and bulbs were fertilised by the manure from our parents’ chooks. A huge weeping deciduous tree in the front yard afforded a play area for visiting grandchildren. The house was big enough for our aunt and family, who lived near Warrnambool, to stay over Christmas.

It had a coal cellar, accessed by a trapdoor on the back verandah, with fed the coke heater.

The house looks much the same in 2019, as it did sixty years ago, when Grandma served cake and tea in beautiful china in the front room to her visitors, and mugs of tea with slabs of bread and butter to workmen on the back verandah.

Xavier College

Our uncle and father, first went as borders to Xavier College for their secondary eduction. When our father began there in 1932, Xavier had already been there for fifty years. It was and still is, the premier Catholic Boys private school in Melbourne.

Initially they boarded at the preparatory school, Burke Hall. The buildings of Burke Hall were put together from a trio of mansions on the hill known as Studley Park, some bought by, others bequeathed to, the Jesuits. It first opened, as Xavier College’s junior school in 1921.

Xavier’s senior School is even older. The South Wing is the original building of Xavier College. The foundations date from 1872, the front dates from the opening of the College in 1878, the back half was completed in 1884. It was listed by the National Trust in 1987.

Xavier’s main chapel would have been being built when our father arrived. It was finally completed in 1934. The chapel is a fine building with a huge dome. I have sung in a concert under that dome, and Sue has been in the audience for another concert there.

Comments

I can hear sleigh bells

13 12 17 15:36 Filed in: Children 1950s | Teenagers 1960s

Christmas has always been special time in our lives. It is not surprising, I suppose, as the whole of society gears up for this event. Now in our multicultural society, Christmas is driven by the commercialisation. When we were growing up, it was because everyone in our world was ‘Anglo’ and many people went to church. For us too, it was one of the few variations from routine, and one of the few times in a year when we went visiting.

Christmas also marked the end of the school year and the beginning of holiday preparations. When we were very young, this involved a wonderful week staying with Pauline, Auntie Marge and Uncle George and later, the huge preparations for camping at Shoreham.

In our minds, Christmas preparations are linked with images of Mum sewing at the kitchen table; cotton ends; bits of material with paper patterns securely pinned to them; standing still to have hems pinned up; and the last minute wrapping of presents amongst the sewing detritus. Dad was packing the trailer and driving to Shoreham to set up the tent. Our parents must have been very busy, but we remember it as a very happy time. Margaret and I remember decorating the tree that was of course a pine tree.

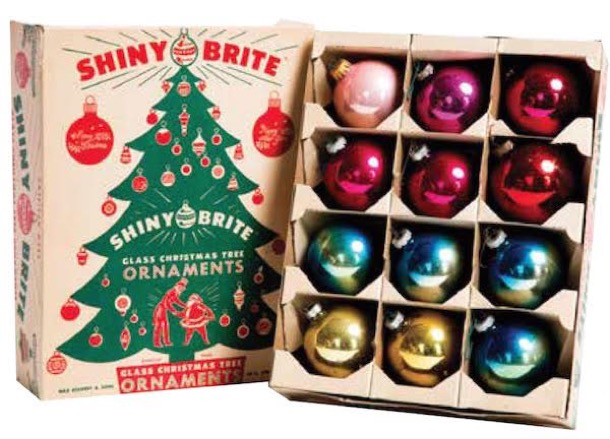

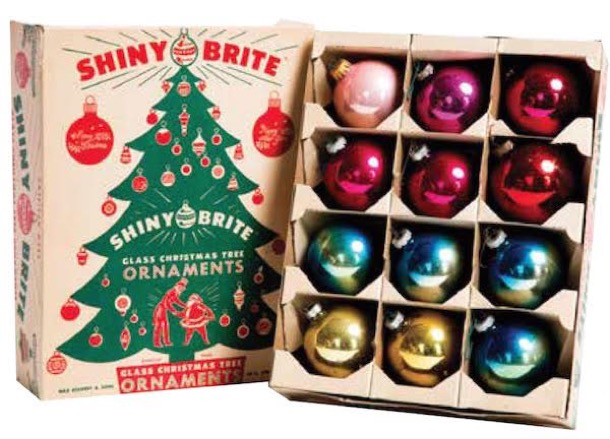

Christmas baubles were made of glass: fragile and expensive.

Choosing the tree was quite a process, as was the decorating, as trees were irregular shapes, not manicured as they are today.

With Mum so busy sewing, it was also easy to slip unnoticed into the dark, tall built-in cupboard in their bedroom, where every year, on the second top shelf, mysterious exciting items in brown paper bags were stored. We remember doing quite a bit of poking and prodding, but never unwrapping and having a real good look. This would have to wait until Christmas morning.

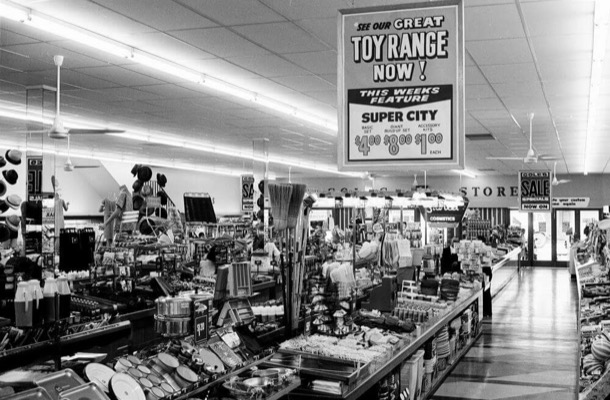

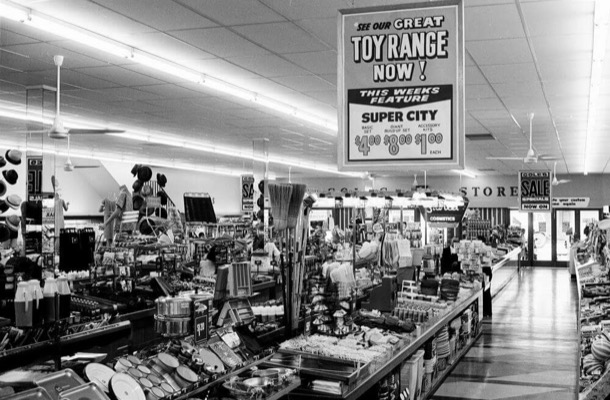

Margaret and I also saved our pocket money for Christmas and bought presents for Aunts, Uncles, Great Aunts and Grandparents. We had wonderful fun in the Coles Emporium in Box Hill choosing the most wonderful pressies.

We choose strong smelling bath salts for Auntie Bert, delightful ornaments for Grandma Bourke, talcum powder for Auntie Tish and often disappointingly, hankies for the men, as they were very hard. The shops, even the department stores, were very, very different. A few Christmas decorations were evident, but shops generally were less cluttered, as there was little if any self service.

Once purchased and examined we wrapped the presents, made and wrote cards, and either posted or delivered them personally on Christmas Day. Sometimes we also made presents. One year it was calendars. We made them with a prepared calendar printed format and found interesting pictures to paste in for each month. Great fun!

Another delightful memory is of the Salvation Army brass bands who marched the suburban streets before Christmas, stopping every now and again to play three or four carols on a corner. If we were lucky they would stop nearby and we could peer out the window and see them in their uniforms playing the shiny brass instruments. It was always disappointing to hear the tread of feet in unison, as they marched away to the next spot.

One such very hot night , Christmas Eve actually, the Salvation Army Band had moved on and apparentIy I convinced Margaret that we could hear sleigh bells. Margaret is not sure of it but I am!

I must have been about seven or eight when my suspicions about the identity of Father Christmas were confirmed, although I did still try to deny it and believe for a few years after that. We were staying in a little fibro holiday house in Rosebud with another family. The children were squashed in together in one room, on beds and mattresses on the floor. Late on Christmas Eve, I saw two figures, our parents, laden with crinkly, crunchy pillowcases, stumbling around the crowded room putting the ‘sacks’ on the respective beds. I remember telling Mum that I had seen them, and being cautioned to keep the knowledge to myself. I did!

Christmas Eve for us didn’t involve special preparations or rituals, other than the placing of a pillow slip on the end of each bed. We called these “sacks”. Sue remembers “hearing” Santa’s sleigh bells one year, and sometimes the Salvos street-corner concert would be on this special night, but generally the excitement began on waking.

As soon as I remembered the specialness of this particular morning, I would reach out my toes and touch the lumpy sack that now took up a good ideal of the bottom of the bed. The crinkle of wrapping paper and the solidity of its contents were thrilling. Sue and I shared a room, and the first one awake would wake the other. I guess we woke the two boys too, or perhaps they woke us up.

The ritual was then for each of us to carry our sacks up the hall to our parents’ room and have a mass unwrapping there, on their bed.

When Sue and I talked at length about our reminiscences of our childhood Christmases, one of us raised the question of what presents we remember. The answer is: hardly any. And yet we had very few toys, and only two occasions, Christmas and birthdays, when we got any.

“Stuff” was very expensive and in short supply when we were little. And clearly it was not terribly important in our lives. In our sacks there were one or two intriguing and fairly roughly wrapped parcels. There might be a toy, maybe some “special” clothes, a bag of mixed lollies, chocolate coins, eaten then and there, and little else. One year we were given hard cover bibles, (not very exciting). Later in the day, we presume there were presents from other family members, but we do not remember the actual items, just the excitement of unwrapping and the specialness of the occasion.

A rare Christmas picture, about 1962. Margaret, Ian and Chris.

One Christmas morning I do clearly remember, was when I woke to find a trail of wool from my sack leading to the large room at the back of the house we called the rumpus room. When I reached the end of it there was a card telling me that my new piano would be placed here. There was a corresponding card on my sack saying that the next year I would start having piano lessons. I had been asking whether I could learn the piano for some time, and, looking back from here, it seems as if I knew that this was going to be very significant in my life.

Other presents we remember which could just as easily have been birthday presents are:

The joint present to all of us of a swing. We got out there early on Christmas morning to use it, and made ourselves sick.

A pogo stick, another joint present.

Roller skates, which attached to our shoes. (Only the boys had bicycles, though we had tricycles when we were really little)

Dolls: mine was black and Sue’s caucasian.

Beach toys, such as bucket and spade, and, later, rubber blow up surf matts.

After we had strewn our parents’ bedroom with paper and eaten far too many lollies and chocolates, we had our usual breakfast of cereal, sugar and milk, put on our “best” dresses, socks and either our school shoes, or sandals (we only owned one pair of each) and headed off to church.

Sue remembers the Christmas church service as “a little less boring than usual”. For me, church was all about the music. The Christmas church service was overflowing with once-a-year-Christians and there was an air of excitement among all age groups.

After church there was a small, not very special lunch at home, and our mother doing last minute wrapping of presents for the afternoon. Then, I guess still wearing our best, (although some of us were quite prone to getting extremely dirty extremely quickly), we headed off for the afternoon at Grandma Bourke’s place.

It is about this part of Christmas Day that I have the clearest recollections.

We have written in another post (“Cut out of the Will” 15/6/2016) about our parents’ ”mixed marriage” and the disapproval with which their union was viewed.

Our mother called her mother in law “Mrs Bourke”, which was also her own name of course. We were aware of the tensions between them, and acutely aware of the warmth and familiarity between “Grandma Bourke” and her other grandchildren, who lived in the country and stayed with her every Christmas. They called her “Gannar”.

Presents were exchanged, as we sat in a circle. Interestingly, while we can remember giving presents to the grown ups, Grandma, Auntie Tish and Uncle Matt, we don’t remember any specifics of the presents we were given.

Mostly, for us, these visits were about the food. Afternoon tea, in the front room, stuffed full of dark furniture, was a grand affair. There was a huge silver teapot with its cosy, on a double decker tea trolley with cups and saucers. There was cake, slices and delicious savouries in huge quantities.

The grownups made conversation, about things that were not of our world: the races, farming the cattle property that Uncle Matt owned in the Western District, television, (Grandma Bourke was a huge fan of Graham Kennedy) and people we didn’t know.

Afterwards we children went outside under the weeping elm tree in the front yard, to play. It is only there I have any memory of interacting with our cousins, and not much there either. They were younger than us, and lived in a very different world. Occasionally our other cousins, Uncle Jack’s children, even less familiar, would come to visit on Christmas Day.

Some years, this was the end of Christmas for us. We went home for a light dinner and woke up to the rest of the holidays, which, in later years, meant six weeks camping at Shoreham.

Sometimes, though, we went on from Grandma Bourke’s in Hawthorn, to Beaumaris and our mother’s sister’s place. After the stiff, tense formality of Grandma Bourke’s, Auntie Marge’s warm welcome and the relaxation of playing with our familiar cousin Pauline, was a huge relief. We would have a wonderful meal and exchange presents lounging around the floor in the spacious living room. There was even a glass of wine (Penfolds Moselle in a flagon) with dinner for some of the adults. Alcoholic drinks did not feature in our parents’ lives.

We did not see our maternal grandparents on Christmas Day. We have no memory of them sharing anything Christmassy with us, even when they were living with us.

Most families have developed Christmas traditions. We remember Christmas as being confined to the day itself and the night before, and we suspect this might have been a common thing in those days. Our family did not entertain. There were never any parties, even family parties. When we look back on this time, and compare it to what kids these days experience as Christmas, it was pretty sparse. Sue and I, reflecting on our childhood Christmases, are aware of, and a bit surprised at, how warmly we remember them.

Christmas also marked the end of the school year and the beginning of holiday preparations. When we were very young, this involved a wonderful week staying with Pauline, Auntie Marge and Uncle George and later, the huge preparations for camping at Shoreham.

In our minds, Christmas preparations are linked with images of Mum sewing at the kitchen table; cotton ends; bits of material with paper patterns securely pinned to them; standing still to have hems pinned up; and the last minute wrapping of presents amongst the sewing detritus. Dad was packing the trailer and driving to Shoreham to set up the tent. Our parents must have been very busy, but we remember it as a very happy time. Margaret and I remember decorating the tree that was of course a pine tree.

Christmas baubles were made of glass: fragile and expensive.

Choosing the tree was quite a process, as was the decorating, as trees were irregular shapes, not manicured as they are today.

With Mum so busy sewing, it was also easy to slip unnoticed into the dark, tall built-in cupboard in their bedroom, where every year, on the second top shelf, mysterious exciting items in brown paper bags were stored. We remember doing quite a bit of poking and prodding, but never unwrapping and having a real good look. This would have to wait until Christmas morning.

Margaret and I also saved our pocket money for Christmas and bought presents for Aunts, Uncles, Great Aunts and Grandparents. We had wonderful fun in the Coles Emporium in Box Hill choosing the most wonderful pressies.

We choose strong smelling bath salts for Auntie Bert, delightful ornaments for Grandma Bourke, talcum powder for Auntie Tish and often disappointingly, hankies for the men, as they were very hard. The shops, even the department stores, were very, very different. A few Christmas decorations were evident, but shops generally were less cluttered, as there was little if any self service.

Once purchased and examined we wrapped the presents, made and wrote cards, and either posted or delivered them personally on Christmas Day. Sometimes we also made presents. One year it was calendars. We made them with a prepared calendar printed format and found interesting pictures to paste in for each month. Great fun!

Another delightful memory is of the Salvation Army brass bands who marched the suburban streets before Christmas, stopping every now and again to play three or four carols on a corner. If we were lucky they would stop nearby and we could peer out the window and see them in their uniforms playing the shiny brass instruments. It was always disappointing to hear the tread of feet in unison, as they marched away to the next spot.

One such very hot night , Christmas Eve actually, the Salvation Army Band had moved on and apparentIy I convinced Margaret that we could hear sleigh bells. Margaret is not sure of it but I am!

I must have been about seven or eight when my suspicions about the identity of Father Christmas were confirmed, although I did still try to deny it and believe for a few years after that. We were staying in a little fibro holiday house in Rosebud with another family. The children were squashed in together in one room, on beds and mattresses on the floor. Late on Christmas Eve, I saw two figures, our parents, laden with crinkly, crunchy pillowcases, stumbling around the crowded room putting the ‘sacks’ on the respective beds. I remember telling Mum that I had seen them, and being cautioned to keep the knowledge to myself. I did!

Christmas Eve for us didn’t involve special preparations or rituals, other than the placing of a pillow slip on the end of each bed. We called these “sacks”. Sue remembers “hearing” Santa’s sleigh bells one year, and sometimes the Salvos street-corner concert would be on this special night, but generally the excitement began on waking.

As soon as I remembered the specialness of this particular morning, I would reach out my toes and touch the lumpy sack that now took up a good ideal of the bottom of the bed. The crinkle of wrapping paper and the solidity of its contents were thrilling. Sue and I shared a room, and the first one awake would wake the other. I guess we woke the two boys too, or perhaps they woke us up.

The ritual was then for each of us to carry our sacks up the hall to our parents’ room and have a mass unwrapping there, on their bed.

When Sue and I talked at length about our reminiscences of our childhood Christmases, one of us raised the question of what presents we remember. The answer is: hardly any. And yet we had very few toys, and only two occasions, Christmas and birthdays, when we got any.

“Stuff” was very expensive and in short supply when we were little. And clearly it was not terribly important in our lives. In our sacks there were one or two intriguing and fairly roughly wrapped parcels. There might be a toy, maybe some “special” clothes, a bag of mixed lollies, chocolate coins, eaten then and there, and little else. One year we were given hard cover bibles, (not very exciting). Later in the day, we presume there were presents from other family members, but we do not remember the actual items, just the excitement of unwrapping and the specialness of the occasion.

A rare Christmas picture, about 1962. Margaret, Ian and Chris.

One Christmas morning I do clearly remember, was when I woke to find a trail of wool from my sack leading to the large room at the back of the house we called the rumpus room. When I reached the end of it there was a card telling me that my new piano would be placed here. There was a corresponding card on my sack saying that the next year I would start having piano lessons. I had been asking whether I could learn the piano for some time, and, looking back from here, it seems as if I knew that this was going to be very significant in my life.

Other presents we remember which could just as easily have been birthday presents are:

The joint present to all of us of a swing. We got out there early on Christmas morning to use it, and made ourselves sick.

A pogo stick, another joint present.

Roller skates, which attached to our shoes. (Only the boys had bicycles, though we had tricycles when we were really little)

Dolls: mine was black and Sue’s caucasian.

Beach toys, such as bucket and spade, and, later, rubber blow up surf matts.

After we had strewn our parents’ bedroom with paper and eaten far too many lollies and chocolates, we had our usual breakfast of cereal, sugar and milk, put on our “best” dresses, socks and either our school shoes, or sandals (we only owned one pair of each) and headed off to church.

Sue remembers the Christmas church service as “a little less boring than usual”. For me, church was all about the music. The Christmas church service was overflowing with once-a-year-Christians and there was an air of excitement among all age groups.

After church there was a small, not very special lunch at home, and our mother doing last minute wrapping of presents for the afternoon. Then, I guess still wearing our best, (although some of us were quite prone to getting extremely dirty extremely quickly), we headed off for the afternoon at Grandma Bourke’s place.

It is about this part of Christmas Day that I have the clearest recollections.

We have written in another post (“Cut out of the Will” 15/6/2016) about our parents’ ”mixed marriage” and the disapproval with which their union was viewed.

Our mother called her mother in law “Mrs Bourke”, which was also her own name of course. We were aware of the tensions between them, and acutely aware of the warmth and familiarity between “Grandma Bourke” and her other grandchildren, who lived in the country and stayed with her every Christmas. They called her “Gannar”.

Presents were exchanged, as we sat in a circle. Interestingly, while we can remember giving presents to the grown ups, Grandma, Auntie Tish and Uncle Matt, we don’t remember any specifics of the presents we were given.

Mostly, for us, these visits were about the food. Afternoon tea, in the front room, stuffed full of dark furniture, was a grand affair. There was a huge silver teapot with its cosy, on a double decker tea trolley with cups and saucers. There was cake, slices and delicious savouries in huge quantities.

The grownups made conversation, about things that were not of our world: the races, farming the cattle property that Uncle Matt owned in the Western District, television, (Grandma Bourke was a huge fan of Graham Kennedy) and people we didn’t know.

Afterwards we children went outside under the weeping elm tree in the front yard, to play. It is only there I have any memory of interacting with our cousins, and not much there either. They were younger than us, and lived in a very different world. Occasionally our other cousins, Uncle Jack’s children, even less familiar, would come to visit on Christmas Day.

Some years, this was the end of Christmas for us. We went home for a light dinner and woke up to the rest of the holidays, which, in later years, meant six weeks camping at Shoreham.

Sometimes, though, we went on from Grandma Bourke’s in Hawthorn, to Beaumaris and our mother’s sister’s place. After the stiff, tense formality of Grandma Bourke’s, Auntie Marge’s warm welcome and the relaxation of playing with our familiar cousin Pauline, was a huge relief. We would have a wonderful meal and exchange presents lounging around the floor in the spacious living room. There was even a glass of wine (Penfolds Moselle in a flagon) with dinner for some of the adults. Alcoholic drinks did not feature in our parents’ lives.

We did not see our maternal grandparents on Christmas Day. We have no memory of them sharing anything Christmassy with us, even when they were living with us.

Most families have developed Christmas traditions. We remember Christmas as being confined to the day itself and the night before, and we suspect this might have been a common thing in those days. Our family did not entertain. There were never any parties, even family parties. When we look back on this time, and compare it to what kids these days experience as Christmas, it was pretty sparse. Sue and I, reflecting on our childhood Christmases, are aware of, and a bit surprised at, how warmly we remember them.

"Cut out of the Will"

15 06 16 16:52 Filed in: Jim

Growing up we had heard many times how our father had been ‘cut out of the will’ by his father because he had married a Protestant and renounced the Catholic faith.

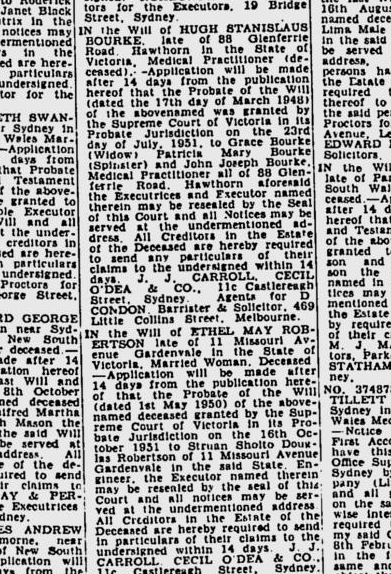

As we were researching the early life of our Catholic grandmother Grace, we stumbled across the application for probate for the will of Doctor Hugh Stanislaus Bourke, our grandfather. His widow Grace, his son Jack, his daughter Patricia are mentioned but no mention of James Vincent Bourke his second son, our father.

Here, published in the Argus Newspaper, was the brutal reality of what this divide really meant in our parent’s lives. It was no small sum: 36,353 pounds. In todays world this would be equivalent to leaving an estate valued at six and a half million dollars.

More shocking is the date, on which the will was written March 17, 1948: not when they married, but three years later, when Alice was only just pregnant with their first child who was not going to be raised as a Catholic. Was this the catalyst?

Australia and the Irish Catholic/English Protestant divide.

In the very earliest days of the NSW penal colony, many of the convicts and early settlers were Irish catholics, and most of the British Military, who ran the prison colony were Anglican protestants.

The first few decades of the colony coincided with unrest and rebellion in Ireland, which was still under English rule. The authorities were nervous of the very large numbers of Irish convicts and settlers, who spoke their own language and had a different religion.

Most of Ireland became a republic and a separate country in 1922. Although there was still unrest in Northern Ireland, which remains part of England to this day, most of the official heat went out of the Irish English divide, though it remained in people’s consciousness.

Australia had an influx of European migrants in the nineteen-forties and fifties, and gradually the clear division of Australian into Catholics and Protestants became blurred, though there was still institutionalised prejudice against Catholics, right up until the 1980s.

The other: the mysterious Catholic world seen through our eyes.

Dark, heavy wooden framed paintings of the Virgin Mary and the Crucified Christ were the mysterious evidence of the Catholicism of our grandmother. We only visited Grandma Bourke’s house three or four times a year for very formal, if delicious, afternoon tea. Our relationship with her too was very formal, a peck on the cheek hello and goodbye and no spontaneous hugs and signs of affection, as we saw our cousins receive.

We knew nothing of this strange Catholic world as we were Protestant and our parents were both heavily involved at St James Presbyterian Church, Wattle Park, where there were a few bare crosses, but no other iconography.

The dark religious ‘icons’ we saw in Grandma’s house were also to be found in Uncle Jack’s house in Glenferrie Road. Most mysterious was the large porcelain statue of Mary. Mother of God, clad in a pale blue robe and further upstairs another large porcelain statue of the Crucified and Risen Christ complete with bleeding nail holes. Gruesome stuff!

When we were growing up, even though we had Catholic relatives, we would never have gone into the Catholic Church. On several occasions we saw, at the local Catholic Church, little girls dressed up as Brides of Christ, lined up and waiting to process into the church for their First Communion.

Nuns in full habit were also very much part of our early memories. I remember back shiny lace up shoes visible under the long heavy black robes, the white starched wimple and veil and, above all, the clanking sound of the Rosary Beads and keys on a chain around their waists.

Even though, by the nineteen forties, there were Catholics in all walks of life, ordinary people still defined themselves and each other by whether they were Catholic or Protestant.

They went to separate schools, even at primary school level. If you went to a Protestant private school, you bought your uniform at Myers. Foys, another department store, catered for the Catholic ones.

Catholics were forbidden to set foot in a Protestant church. One story from this time is of the brothers of a Catholic woman marrying a Protestant forced to stand outside and watch the ceremony through the window. When Protestants and Catholics married it was called a “mixed marriage”

There was lots of name calling… “Micks”, “papists”, “proddy dogs”. Our father, attending the Catholic School in his home town of Koroit during the nineteen thirties, told us the story of him running home, chased by kids from the state school, turning and calling “proddy dogs, jump like frogs” or perhaps it was the others calling him a “Catholic dog” … probably both.

So when our father, Jim, told his Irish Catholic parents about his new girlfriend, there were probably alarm bells right from the beginning. Jim and Alice met at work, the Maribyrnong Munitions Factory.

They married in 1945, a couple of months before the end of the war. She did not dress as a bride, because it was still war time, and they had a quiet ceremony in the Congregational Church in Surrey Hills, near Alice’s home and a reception at Wattle Park Chalet.

The couple lived with her parents, Alfred and Alfreda, until they built and moved into their own house in the early nineteen fifties. Alice’s parents seem to have been very tolerant. Their eldest daughter had married a Hungarian Jew a few months earlier and now their other daughter, a Catholic. Theirs was a working class family, educated and valuing education, but without much money or position in society.

Jim’s parents were from a different class as well as a different religion. Grace, as we have discovered had been a society girl and Hugh, a well respected country doctor. They did not come to the wedding. We can only imagine the conversations, the arguments, the pleading. To them, Jim’s parents, their precious son was denying himself an afterlife in Heaven, and bringing shame on the family. Any children born to this marriage would be viewed as illegitimate. In the eyes of the Catholic Church our parents were not married.

One “family story” tells of Jim’s sister, Tish, writing a letter pleading for them to “marry properly”. As children we knew that our father had “left the Catholic Church” in order to marry our mother and that he had been “cut out of the will”. It is part of our family mythology. We were aware of our mother’s bitterness at our family’s financial struggles. We witnessed the stiff courtesy with which she greeted her mother-in-law, who she always addressed as Mrs Bourke.

Now, looking at the stark reality of this newspaper article, we feel a little of her outrage. We understand better the enormity of that decision, the extraordinary timing of Hugh’s change of will, the sense of being the ‘black sheep” family that hung over us when we visited out Grandmother.

Grace McCormack, our other grandmother.

25 05 16 17:04 Filed in: Jim

Until last week we knew very little about our paternal Grandmother, Grace. We both had the feeling from our father that she had been a “somebody”. I remember him referring to her as “Gracie McCormack”, as if that meant something special. We knew that, as the doctor’s wife in Koroit, she had been an important person. Then we did a little research:

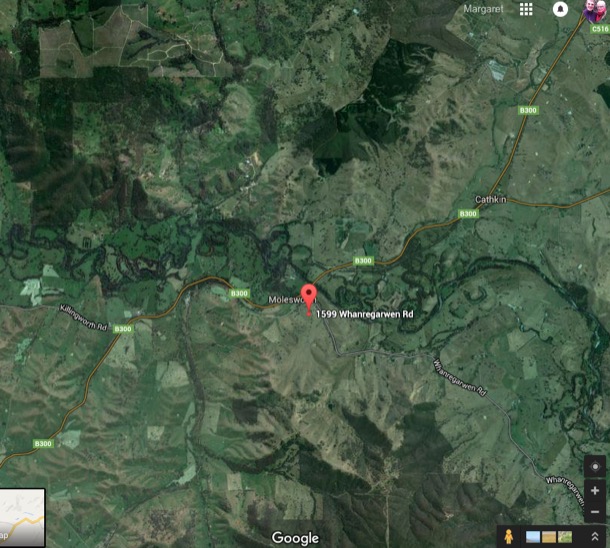

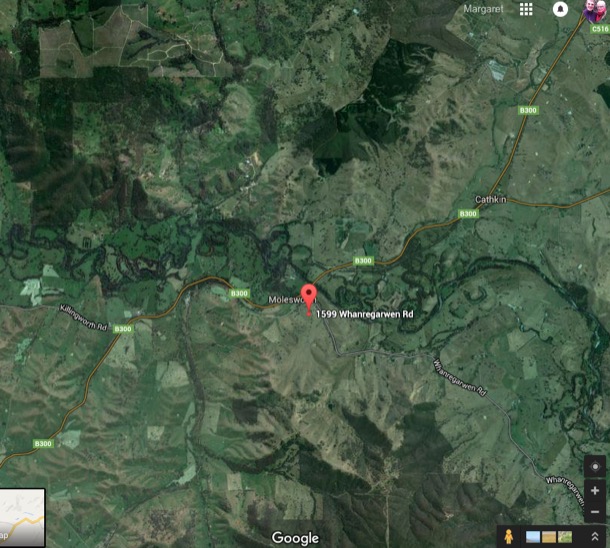

Grace McCormack was born in 1893 at the family home, called Balham Hill in Molesworth, near Yea. This is only nineteen kilometres from Sue and Jono's new property Billy Goat Hill.

Grace's father, John and mother Johanna, were highly respected and wealthy members of the community, who had bought the huge grazing property, nearly 15,000 acres, in 1886.

The house, still there today, had been built by one of the first white settlers in the area, Edward Cotton. It was near the Goulburn River, built of bricks made on the property.

The address is 1599 Whanregarwen Road MOLESWORTH

When he first arrived in the district he (Edward Cotton, who later published a book about Australian birds) wrote of the view over the valley from the Balham Hill homestead in his correspondence." I was much pleased with the beauty of the spot. The trees are rather thinly scattered over the flat, and there are extensive lagoons”. ”White cockatoos, king parrots, parakeets, eagle hawks, several species of honey-suckers and numerous tribes of smaller birds, including the bellbird, the superb warbler, etc., were plentifully scattered about this station. Ducks, black swans, divers, kingfishers, herons were constantly seen on or about the lagoons”.

HISTORY OF BALHAM HILL (from the Shire of Murrindindi Heritage Report)

The original homestead was built for Edward Cotton in 1842 or '43 using bricks made on the property. A report on the request for a pre-emptive right of June 1854 refers to a brick home, woolshed, outhouses and stables. Edward Cotton, the first squatter of Balham Hill, was born in 1803 Balham Hill, Clapham Common near London. Despite his ambitions, he failed as a pastoralist and sold Balham Hill in 1848. He died from drowning at Moorabbin in 1860, one a week after being suspended from his position as Registrar (Chief Clerk) of the County Court for 'extravagance and financial mismanagement'. In 1886 the property was sold by William Merry to John McCormack. He and his wife Johanna had five children, one of whom, Aloysius, died as an infant. The remaining children, Jane, Grace, Leo and Cyril grew up at Molesworth and attended Molesworth State School. In the early 1900s John McCormack rebuilt the homestead, retaining and incorporating into the new building some of Cotton's original homestead. The front rooms and hall were built for McCormack. The E-W passage is believed to be the front verandah of the original building, and there may have been many more rooms at the rear. During the McCormacks' time there was a circular drive at the front which was lost when road works altered the entrance. In 1930, following the death of John McCormack, the property was divided. Leo retained Balham Hill and married Zillah Maling. In 1942 Leo sold Balham Hill and moved to Melbourne. Cyril, who married Josephine Conlan in June 1930, took over a large area near Cottons Pinch and a home was built on this section. The property was named Alencon after a village in northern France. An early large orchard on the east side of the house, which includes the establishment of a Mulberry tree, was still in existence in 1994. An early rose garden once occupied the west side.

It is believed that the house originally had 17 rooms, but some of them were removed in the mid-20th century.

Births, deaths and weddings have all taken place at Balham Hill. Notably, Clara Ridd was born there during the 1870 flood. It is thought Balham Hill provided accommodation to travellers en route to the north east.

Grace was the second child. She had an older sister, Jane and three younger brothers, one of whom, Aloysius, died aged only ten months. He is buried in the Yea Cemetery. The other two boys were called Leo and Cyril. The four children all attended Molesworth State School.

John was a Justice of the Peace, a community leader, who could sign official documents and witness things for people. He donated the land for the Molesworth Community Hall.

John and Johanna had the house remodelled in the early 1900s. It had 17 rooms and a circular driveway.

The children were sent away to boarding school for their secondary education. The boys probably went to Xavier College, the girls to the Convent of Mercy in Fitzroy:

Jane was married almost exactly one month before the First World War began, in 1914: a grand affair at St Patrick’s Cathedral. Grace was her bridesmaid. The newspaper coverage of this social event is worth a read:

MR. T. M. B. COFFEY TO MISS J. McCORMACK.

The marriage of Mr. T. M. B. Coffey, third son of the late John Coffey and Mrs. Coffey, of “Kewell," Riversdale Road, Hawthorn, and Miss Jean McCormack, elder daughter of Mr. John McCormack, of "Balham Hill” Molesworth was celebrated at St. Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne, on 27thMay.

The Rev. Father O'Reilly (Castlemaine) officiated. He

was assisted by the Rev. Father Ellis. The altar was beautifully decorated with white flowers. Miss Anderson was at the organ, and played Lohengrin's Wedding March and other beautiful music. The bride, who was given away by her father, wore a gown of soft Oriental satin, gracefully draped in straight

lines, and veiled with a short tunic of fine silk shadow lace. The beautiful court train was lined with shell pink, and finished with true lovers' knots and orange blossom. The Angel sleeves were caught and weighted with pearl tassels. The crossed bodice was of pearl embroidery, veiled with silk shadow lace. A veil of beautiful old Limerick lace (lent by the nuns) was worn, and a shower bouquet of white azaleas and fern was carried. The bridesmaid (Miss Grace McCormack) was frocked in dainty ivory crepe-de chine, the tunic of soft ninon, edged with marabout. The bodice, of soft shadow lace, was veiled with ninon, and finished with a sash of rose-pink velvet. The black velvet hat was wreathed with small winter berries and forget-me-nots. A bouquet of La France roses was carried. The train-bearers were Miss Kathleen McCormack (bride's god-child and cousin) and Miss Margaret Armond (bridegroom's god-child and cousin). They wore dainty little early Victorian dresses of white crepe-de^chine, with empire sashes, of ninon, the neck and sleeves prettily finished with white marabout. Their ninon capes were set with trails of pale pink, and they carried 1830 bouquets of small

pink roses and silver bags (gifts of bridegroom). The bridegroom's gift to the bride was a pianola piano; to bridesmaids, Nellie Stewart bangle; bride to bridegroom, beautifully fitted dressing case. Mr. Leo. McCormack (brother of bride) was best man. The bride's mother was gowned in black cashmere de soie, the skirt gracefully draped with beautiful Chantilly lace; the bodice of fine black lace, embroidered in gold, and finished with soft white tulle. A black velvet hat, set with ostrich plumes, was worn, and a bouquet of violets was carried. The bridegroom's mother and sister were unable to be present,

being at present on a visit to Dr. Coffey, in Dublin. A reception was held at, the Grand Hotel, followed by a wedding' luncheon to about seventy guests.

Later the bride and bridegroom left for Sydney, en route to New Zealand. The bride travelled in blue coat and skirt, rolled back with collar of white cloth. A black velvet hat, set with a white plume was also worn. The presents were numerous and costly, and included several substantial cheques.

So Grace was given present of a plain gold "Nellie Stewart bangle" These had become a popular fashion accessory for young Australian women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Usually worn on the upper arm, they were an emulation of Nellie Stewart's style. (a singing celebrity of the time)

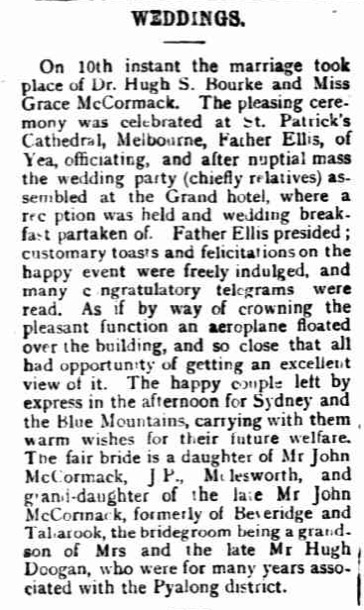

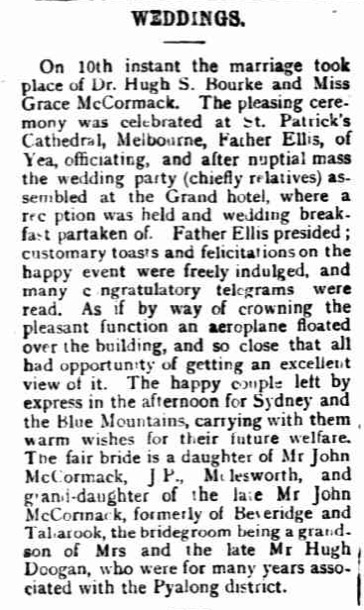

Four years later, at the end of a gruelling four years of war, Grace herself married Hugh Stanislaus Bourke. She was twenty-five. One can’t help but speculate about those four years. How many friends did she lose? Perhaps even an earlier sweetheart.

We know her two brothers survived, because the land was divided between them when their father died in 1930.

Their wedding was a less grand affair, though still held at St Pat’s Cathedral. (Note the excitement of the aeroplane.)

On 10th instant the marriage took place of Dr. Hugh S. Bourke and Miss Grace McCormack. The pleasing ceremony was celebrated at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Melbourne, Father Ellis, of Yea, officiating, and after nuptial mass the wedding party (chiefly relatives) assembled at the Grand hotel, where a reception was held and wedding breakfast partaken of.

Father Ellis presided; customary toasts and felicitations on the happy event were freely indulged, and many congratulatory telegrams were read.

As if by way of crowning the pleasant function an aeroplane floated over the building, and so close that all had opportunity of getting an excellent view of it. The happy couple left by express in the afternoon for Sydney and the Blue Mountains, carrying with them warm wishes for their future welfare. The fair bride is a daughter of Mr John McCormack, J.P., Molesworth, and granddaughter of the late Mr John McCormack, formerly of Beveridge and Tallarook, the bridegroom being a grand son of Mrs and the late Mr Hugh Doogan, who were for many years associated with the Pyalong district.

Hugh had been registered as a doctor in 1907, and was, by 1918, practising in the western Victorian town of Koroit, where Grace and Hugh raised their three children.

They moved to 88 Glenferrie Road Hawthorn, home and GP surgery, during the 1930s, and stayed there until Hugh’s death in 1951, when the practice was taken over by their eldest son John.

Grace, then aged 58, moved nearby and then to Urquhart Street, Hawthorn, where we can remember visiting her, when we were children.

And a little bit about Grace's paternal grandparents:

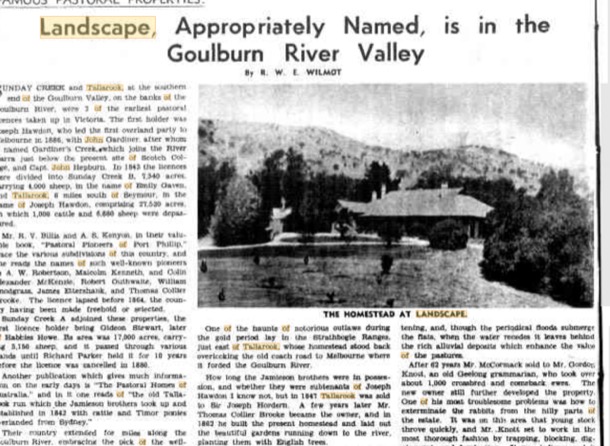

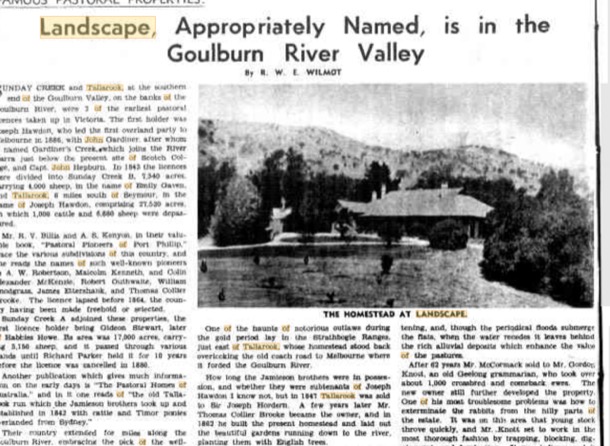

Grace comes from quite a line of early Victorian settlers. Grace’s grandfather, also called John McCormack, had large land holdings nearby in Beveridge and Tallarook. Grace was named after her grandmother Grace Bridget, who was reported to be a generous women who was very interested in the social scene. First they lived at ‘Red Barn Farm’ in Beverage, a dairy farm with cheese making facilities including steam driven machinery. They moved to ‘Landscape’ at Tallarook in 1867. It was a much larger gazing property, also with Goulburn River frontage. Grace’s grandmother died at ‘Landscape' having spent 69 of her 83 years in the district.

A section of this article reads:

When Tallkarook was still further subdivided in 1867, the homestead block of 3000 acres was purchased by Mr J McCormack, who named his property “Landscape”. It was only natural that in sixty years, a district so favoured by Nature within fifty-five miles of Melbourne, on the main highway from Melbourne to Sydney, should progress, and in that development Landscape shared.

The Goulburn River, with its rich alluvial flats, flanked by slopes between the frontages and the granite hills, make up an ideal property for fattening, and, though the periodical floods submerge the flats, when the water recedes it leaves behind the rich alluvial deposits which enhance the values of the pastures.

And, as an amazing postscript, Jono remembers that his mother, Janie, was school friends with a girl called Janet Essington-Lewis. Her father was the head of BHP and owned Landscape in the 1930s. Janie used to go riding at Landscape with Janet.

Grace McCormack was born in 1893 at the family home, called Balham Hill in Molesworth, near Yea. This is only nineteen kilometres from Sue and Jono's new property Billy Goat Hill.

Grace's father, John and mother Johanna, were highly respected and wealthy members of the community, who had bought the huge grazing property, nearly 15,000 acres, in 1886.

The house, still there today, had been built by one of the first white settlers in the area, Edward Cotton. It was near the Goulburn River, built of bricks made on the property.

The address is 1599 Whanregarwen Road MOLESWORTH

When he first arrived in the district he (Edward Cotton, who later published a book about Australian birds) wrote of the view over the valley from the Balham Hill homestead in his correspondence." I was much pleased with the beauty of the spot. The trees are rather thinly scattered over the flat, and there are extensive lagoons”. ”White cockatoos, king parrots, parakeets, eagle hawks, several species of honey-suckers and numerous tribes of smaller birds, including the bellbird, the superb warbler, etc., were plentifully scattered about this station. Ducks, black swans, divers, kingfishers, herons were constantly seen on or about the lagoons”.

HISTORY OF BALHAM HILL (from the Shire of Murrindindi Heritage Report)

The original homestead was built for Edward Cotton in 1842 or '43 using bricks made on the property. A report on the request for a pre-emptive right of June 1854 refers to a brick home, woolshed, outhouses and stables. Edward Cotton, the first squatter of Balham Hill, was born in 1803 Balham Hill, Clapham Common near London. Despite his ambitions, he failed as a pastoralist and sold Balham Hill in 1848. He died from drowning at Moorabbin in 1860, one a week after being suspended from his position as Registrar (Chief Clerk) of the County Court for 'extravagance and financial mismanagement'. In 1886 the property was sold by William Merry to John McCormack. He and his wife Johanna had five children, one of whom, Aloysius, died as an infant. The remaining children, Jane, Grace, Leo and Cyril grew up at Molesworth and attended Molesworth State School. In the early 1900s John McCormack rebuilt the homestead, retaining and incorporating into the new building some of Cotton's original homestead. The front rooms and hall were built for McCormack. The E-W passage is believed to be the front verandah of the original building, and there may have been many more rooms at the rear. During the McCormacks' time there was a circular drive at the front which was lost when road works altered the entrance. In 1930, following the death of John McCormack, the property was divided. Leo retained Balham Hill and married Zillah Maling. In 1942 Leo sold Balham Hill and moved to Melbourne. Cyril, who married Josephine Conlan in June 1930, took over a large area near Cottons Pinch and a home was built on this section. The property was named Alencon after a village in northern France. An early large orchard on the east side of the house, which includes the establishment of a Mulberry tree, was still in existence in 1994. An early rose garden once occupied the west side.

It is believed that the house originally had 17 rooms, but some of them were removed in the mid-20th century.

Births, deaths and weddings have all taken place at Balham Hill. Notably, Clara Ridd was born there during the 1870 flood. It is thought Balham Hill provided accommodation to travellers en route to the north east.

Grace was the second child. She had an older sister, Jane and three younger brothers, one of whom, Aloysius, died aged only ten months. He is buried in the Yea Cemetery. The other two boys were called Leo and Cyril. The four children all attended Molesworth State School.

John was a Justice of the Peace, a community leader, who could sign official documents and witness things for people. He donated the land for the Molesworth Community Hall.

John and Johanna had the house remodelled in the early 1900s. It had 17 rooms and a circular driveway.

The children were sent away to boarding school for their secondary education. The boys probably went to Xavier College, the girls to the Convent of Mercy in Fitzroy:

Jane was married almost exactly one month before the First World War began, in 1914: a grand affair at St Patrick’s Cathedral. Grace was her bridesmaid. The newspaper coverage of this social event is worth a read:

MR. T. M. B. COFFEY TO MISS J. McCORMACK.

The marriage of Mr. T. M. B. Coffey, third son of the late John Coffey and Mrs. Coffey, of “Kewell," Riversdale Road, Hawthorn, and Miss Jean McCormack, elder daughter of Mr. John McCormack, of "Balham Hill” Molesworth was celebrated at St. Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne, on 27thMay.

The Rev. Father O'Reilly (Castlemaine) officiated. He

was assisted by the Rev. Father Ellis. The altar was beautifully decorated with white flowers. Miss Anderson was at the organ, and played Lohengrin's Wedding March and other beautiful music. The bride, who was given away by her father, wore a gown of soft Oriental satin, gracefully draped in straight

lines, and veiled with a short tunic of fine silk shadow lace. The beautiful court train was lined with shell pink, and finished with true lovers' knots and orange blossom. The Angel sleeves were caught and weighted with pearl tassels. The crossed bodice was of pearl embroidery, veiled with silk shadow lace. A veil of beautiful old Limerick lace (lent by the nuns) was worn, and a shower bouquet of white azaleas and fern was carried. The bridesmaid (Miss Grace McCormack) was frocked in dainty ivory crepe-de chine, the tunic of soft ninon, edged with marabout. The bodice, of soft shadow lace, was veiled with ninon, and finished with a sash of rose-pink velvet. The black velvet hat was wreathed with small winter berries and forget-me-nots. A bouquet of La France roses was carried. The train-bearers were Miss Kathleen McCormack (bride's god-child and cousin) and Miss Margaret Armond (bridegroom's god-child and cousin). They wore dainty little early Victorian dresses of white crepe-de^chine, with empire sashes, of ninon, the neck and sleeves prettily finished with white marabout. Their ninon capes were set with trails of pale pink, and they carried 1830 bouquets of small

pink roses and silver bags (gifts of bridegroom). The bridegroom's gift to the bride was a pianola piano; to bridesmaids, Nellie Stewart bangle; bride to bridegroom, beautifully fitted dressing case. Mr. Leo. McCormack (brother of bride) was best man. The bride's mother was gowned in black cashmere de soie, the skirt gracefully draped with beautiful Chantilly lace; the bodice of fine black lace, embroidered in gold, and finished with soft white tulle. A black velvet hat, set with ostrich plumes, was worn, and a bouquet of violets was carried. The bridegroom's mother and sister were unable to be present,

being at present on a visit to Dr. Coffey, in Dublin. A reception was held at, the Grand Hotel, followed by a wedding' luncheon to about seventy guests.

Later the bride and bridegroom left for Sydney, en route to New Zealand. The bride travelled in blue coat and skirt, rolled back with collar of white cloth. A black velvet hat, set with a white plume was also worn. The presents were numerous and costly, and included several substantial cheques.

So Grace was given present of a plain gold "Nellie Stewart bangle" These had become a popular fashion accessory for young Australian women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Usually worn on the upper arm, they were an emulation of Nellie Stewart's style. (a singing celebrity of the time)

Four years later, at the end of a gruelling four years of war, Grace herself married Hugh Stanislaus Bourke. She was twenty-five. One can’t help but speculate about those four years. How many friends did she lose? Perhaps even an earlier sweetheart.

We know her two brothers survived, because the land was divided between them when their father died in 1930.

Their wedding was a less grand affair, though still held at St Pat’s Cathedral. (Note the excitement of the aeroplane.)

On 10th instant the marriage took place of Dr. Hugh S. Bourke and Miss Grace McCormack. The pleasing ceremony was celebrated at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Melbourne, Father Ellis, of Yea, officiating, and after nuptial mass the wedding party (chiefly relatives) assembled at the Grand hotel, where a reception was held and wedding breakfast partaken of.

Father Ellis presided; customary toasts and felicitations on the happy event were freely indulged, and many congratulatory telegrams were read.

As if by way of crowning the pleasant function an aeroplane floated over the building, and so close that all had opportunity of getting an excellent view of it. The happy couple left by express in the afternoon for Sydney and the Blue Mountains, carrying with them warm wishes for their future welfare. The fair bride is a daughter of Mr John McCormack, J.P., Molesworth, and granddaughter of the late Mr John McCormack, formerly of Beveridge and Tallarook, the bridegroom being a grand son of Mrs and the late Mr Hugh Doogan, who were for many years associated with the Pyalong district.

Hugh had been registered as a doctor in 1907, and was, by 1918, practising in the western Victorian town of Koroit, where Grace and Hugh raised their three children.

They moved to 88 Glenferrie Road Hawthorn, home and GP surgery, during the 1930s, and stayed there until Hugh’s death in 1951, when the practice was taken over by their eldest son John.

Grace, then aged 58, moved nearby and then to Urquhart Street, Hawthorn, where we can remember visiting her, when we were children.

And a little bit about Grace's paternal grandparents:

Grace comes from quite a line of early Victorian settlers. Grace’s grandfather, also called John McCormack, had large land holdings nearby in Beveridge and Tallarook. Grace was named after her grandmother Grace Bridget, who was reported to be a generous women who was very interested in the social scene. First they lived at ‘Red Barn Farm’ in Beverage, a dairy farm with cheese making facilities including steam driven machinery. They moved to ‘Landscape’ at Tallarook in 1867. It was a much larger gazing property, also with Goulburn River frontage. Grace’s grandmother died at ‘Landscape' having spent 69 of her 83 years in the district.

A section of this article reads:

When Tallkarook was still further subdivided in 1867, the homestead block of 3000 acres was purchased by Mr J McCormack, who named his property “Landscape”. It was only natural that in sixty years, a district so favoured by Nature within fifty-five miles of Melbourne, on the main highway from Melbourne to Sydney, should progress, and in that development Landscape shared.

The Goulburn River, with its rich alluvial flats, flanked by slopes between the frontages and the granite hills, make up an ideal property for fattening, and, though the periodical floods submerge the flats, when the water recedes it leaves behind the rich alluvial deposits which enhance the values of the pastures.

And, as an amazing postscript, Jono remembers that his mother, Janie, was school friends with a girl called Janet Essington-Lewis. Her father was the head of BHP and owned Landscape in the 1930s. Janie used to go riding at Landscape with Janet.