Auntie Bert, a "sterling character"

These three young women are our grandmother Alfreda on the left, with her two younger sisters, Beatrice in the middle and Berta on the right.

Alfreda’s set jaw and determined look reflect her independence and demand for an education. I fancy I can see both the rebel and the farmer in Beatrice’s broad face. But look at the gentle, faraway, passive prettiness of Berta. What experiences are already clouding her young face?

About ten percent of the whole of Australia’a population, the country’s young, fit men, set off to war in 1914. More than half of them were killed, gassed, wounded or taken prisoner. There was no such diagnosis as “post traumatic stress”, but we can extrapolate from the modern experience of returning soldiers.

What happened to the equivalent ten percent of young women, who, in different circumstances, would have been marrying them and having their babies?

Our Auntie Bert became one of the many “maiden aunts” of that very specific generation. The family lore is that she “had opportunities” to marry but “chose to stay in the bosom of her family”. We do not know what the reality of her young life was. Had she been a boy, she would have been one of the 417,000 men who enlisted. One would presume that virtually all the young men she might have had a romantic interest in… brothers of her friends, boys from church, at work, on the train, in her neighbourhood… nearly all would have been absent for four years from when she was 18 until she was 22.

Berta Holm was born in 1896. Her childhood and early adult life was spent in St Kilda.

The family story is that Berta and Beatrice unlike their older sister, Alfreda, did not hunger for an education.

Alice and Marge said this in quite a disapproving tone, which made us wonder about the accuracy of the statement, that Auntie Bert left school at Grade 4, declaring that she would prefer to help her mother at home. In Grade 4 she would have been nine or ten!

At the time Victoria was a progressive state and proud to be the first Australian state to create a system of free, secular and compulsory education. This legislation introduced in 1872, required all children aged 6-15 years to attend school unless they had a reasonable excuse. Schools were built, and a system of inspectors employed to enforce compulsory education. Fines for non-attendance were five shillings and increased for further offences. Did Auntie Bert leave school at the tender age of nine or ten? We think it more likely that she attended a State school, maybe unwillingly and, after trying a private school for young ladies, left at the age fifteen. Their disapproval of the lack of enthusiasm for education, compared to their own mother’s, probably colours the story about their aunt. The view of Auntie Bert we were brought up with, was that she was good with her hands, but, to soften and elevate this statement in true Holm fashion, it was followed by, she was a superb craftswoman and much in demand: not academic but exceptional.

Some time after she left school Berta went to work in Flinders Lane.

At that time Flinders Lane was the centre of the ‘rag trade’ where many Jewish firms had their businesses. Amongst them was Slutskins, for whom both Berta and Beatrice worked doing ‘white work’. Whitework embroidery is the general term for hand embroidery worked with white threads on white fabrics. It is one of the most elegant and timeless styles of embroidery and was used on underwear, night gowns, table linen, handkerchiefs, baby bonnets, christening gowns and many other small items.

After some experience in this area Berta became forewoman, in charge of a group of other women.

We only have Alice and Marge’s childhood recollections from which to piece together Berta’s life.

In early 1925, when she was twenty-nine, perhaps moving away from her parents’ home for the first time, she left her job, probably that responsible position as forewoman. She went, for an unspecified time, to the country, to help her married sister with a toddler and a baby, and to help serve in her brother in law’s hardware shop.

Alfreda had given birth to Alice, our mother, in 1923. She had had a terrible time, alone, during her first delivery, resulting in the death of the baby. We don't know anything about Marge’s birth or the subsequent few years, except that they were quite near to family help. But when Alice was fifteen months old, Alf and Alfreda moved to Bacchus Marsh. Alfreda was “weak from the birth”. The descriptions of her crying, while scrubbing the floor and having to spend whole days in bed, apparently requiring the help of her unmarried sister, makes us think of post natal depression.

Alf too had what we would today call “mental health issues”. He was a gentle, quite scholarly person, and the business venture in Bacchus Marsh, on the eve of the Great Depression, took a toll on his health. It is no wonder Marge and Alice remember Auntie Bert as a tower of strength and support.

In 1928, the old dry house they had been living in caught fire. At the top of the burning staircase were the little girls in their nighties, Alf sedated, because he was in the midst of a “nervous breakdown”, Alfreda, reportedly trying to find her stockings, and Bert, who carried Alice down the stairs. Marge was carried down by her father, finally awake.

The destitute family were taken in by “the Pierces”. Nell Pierce was a lifelong friend of Auntie Bert. Did they meet there at Bacchus Marsh? We don't know.

The family stayed on for at least a year in Bacchus Marsh, but Berta moved back to Melbourne, once again moving in with her parents, probably her only option.

Now in her early thirties and unmarried Berta must have turned her attention to a job. As far as we know this is when she decided to start her own business as a dressmaker. At first she worked from her bedroom, building her business and reputation.

The business was eventually profitable enough to allow her to move to premises in Riversdale Road, Middle Camberwell and then to Burke Road in Camberwell, just over the junction.

I can remember the junction premises quite vividly. It was one big room on the first floor. Big windows looked out onto Burke Road, letting in light and sunshine that fell on the big work tables. Several dressmakers dummies stood in the corner where the fitting room was screened by curtains. It seemed a very busy place.

The big tables, that dominated the space were covered in the paraphernalia of dressmaking. There were several sewing machines, many reels of sewing cotton, several pairs of big dressmakers shears, other dressmaking scissors and many tins of pins. Rolls of fabric and garments in various stages of construction took up the rest of the table space. Another woman was sewing at the table, presumably an employee, so business must have been good. We were probably there for a fitting, as Auntie Bert made ‘good clothes’, for Mum. These beautifully tailored clothes were worn to Church and were for special occasions, including weddings:

She also made us beautiful clothes including these woollen dresses:

Auntie Bert had an account at Ball & Welch, a prominent department store in Finders Street, Melbourne. She needed an account for her business and a reliable source of good quality fabric for her clients. Its four floors occupied one third of the total block and stretched between Flinders Street and Flinders Lane.

Its many departments included gloves, umbrellas and handkerchiefs, fabrics, furniture, china, millinery, furs and corsets. At one time twenty-six assistants were devoted to the sale of lace alone.

Members of the family were generously given access to Auntie Bert’s account, making it possible to buy items on account and pay later. This was very useful at times, as there was no such thing as Credit Cards. At the end of the month, Auntie Bert sent out letters to all those who had used the account, and we reimbursed her by cheque. This was probably quite a task, not only the arithmetic, but also the sending out of all the individual letters.

I can remember enjoying trips to Ball&Welch. The lifts were staffed by attendants in uniform who recited the list of items available at each level as the lift rose between floors. Parcels were wrapped up in brown paper and string, on huge wooden counters. The expert shop assistants were reserved, formal and a little forbidding to a young child. The exchange of payment was quite a process. The shop assistants' job was to serve the customers, not handle the money. When payment was made, it was placed, with the hand written docket, in a metal canister that went shooting on wires across the departments and then upstairs to the Accounts Department. The docket was checked, change inserted, a receipt written and the canister whizzed back from whence it had come. Transaction complete.

The cash-ball system worked reasonably well, but the rails were intrusive and the interior layout of some stores did not allow certain counters or departments to be connected by inclined tracks. The ingenious Lamson then hit upon the concept of the “aerial railway” and set about tinkering with a gondola-like design, which became known as the wire-line or cable-carrier.

By the late 1880s, sales staff could secure cash inside a small wooden jar or canister, suspended by wheels from a taut wire that ran overhead from the sales desk to the cashier’s station, which was typically a cage-like booth situated in the center of the store. By tugging firmly on a spring-loaded cord or lever known as the “propulsion,” the canister would be catapulted along the wire, reaching its destination in mere seconds.

The cashier could then “return fire” with change and a receipt. Cashiers who worked in booths on levels above the sales floor could simply release the canister and let gravity return it to the appropriate counter.

Ball and Welch closed its doors in 1970, the end of an era .

Berta’s sister, Beatrice had taken up dairy farming in the early 1950s, near Cockatoo, in the Dandenong Ranges. The bulk of the work was done by her husband, and three sons. In 1955, the wife of Rob, the middle son, died, leaving a baby daughter, Julie, to be raised by her grandmother.

Into the breach stepped Berta. She moved into a small bedroom in the farm house, and became a second mother to Julie. We remember her room. It had been part of the farmhouse verandah, and the whole room was about twice the size of the single bed. It was neat, sparse and dark.

Our memory of Auntie Bert at the farm is solely inside the farm house. Unlike Auntie Beat, who mucked out the pigs, wearing layers of old jumpers and a woollen beanie, Auntie Bert was always nicely dressed. We remember her in well-cut woollen skirts, stockings and heeled court shoes, with classy jumpers and cardigans. We picture the two of them in the kitchen, both wearing aprons, turning out scones and cakes on the wood stove. Auntie Bert became a permanent and valuable member of the family, looking after the “boys” and Julie.

While her main home and focus was life at the farm, Auntie Bert continued, as she had her whole life, to be the family helper and nurse. She had looked after both her own parents in their final years, and she came to live with us to help out with her elder sister: our Nana, Alfreda, who had dementia. We remember her as a quiet unobtrusive presence in our home. A few years later she came again and helped with Alf, our grandfather, in his final weeks.

So Alice saw first hand, the skill and care of Berta’s nursing:

Apart from staying temporarily with other members of the family, usually to help out during family crises, Berta lived there at the farm, until her death in 1976, aged 80.

Alice reflected on Berta’s death and the simple generous life she lived:

From left to right, Nana, Auntie Bert and Alice:

The Farm

About 1950, our mother’s aunt, Beat, and her husband Bill sold up their grocery store and their Balwyn house, took their youngest son out of school, and bought a dairy farm in the Dandenong Ranges at Nangana, near Cockatoo.

It was called “Sefton Park”, but it became “The Farm” to us, as we were growing up, and it was one of the very, very few places we visited socially.

By the time we were regularly visiting The Farm, the eldest son, Doug had married and moved out. He became a bus driver and spent his whole life living at Avonsleigh, near Emerald.

The next son, Rob, had married young, built another house on the property and had a child, Julie. Rob’s wife, Pat, died of breast cancer when Julie was still a baby, and Rob moved back to his family home. About that time our mother’s unmarried aunt, Bert, moved to The Farm, presumably to help her sister with this motherless baby.

So this rural property supported Beat and Bill, Rob and his daughter Julie, youngest son John, and Beat’s sister Bert.

Auntie Beat and Uncle Bill:

Down at the creek. From left to right (we think): Auntie Beat, Uncle Bill, Rob, Pat, Doug and a neighbour or visitor:

When I picture the farm and its people, in the 1950s, I see Auntie Beat and the men in layers of worn out hand knitted woollens: shapeless jumpers and cardigans, beanies, fingerless gloves, scarves. Auntie Beat wears heavy woollen skirts, thick stockings and socks. By the back door are a row of huge gumboots. Everywhere out side the house is mud, and away from the immediate house and garden, they all wear gumboots. In the dairy they wear heavy canvas coats or aprons. In the house, images of checked aprons, floury hands come to mind.

The journey to the farm with four children in the back seat, or perhaps Chris on Mum’s knee, always seemed a happy and interesting trip. It was about forty-seven kilometres from Box Hill, mostly through farmland, orchards and bush, and probably took us about an hour and a half.

The first highlight was Bennett’s Cottage in Burwood Road, on top of the hill just past Station Street. The crumbling walls of the wattle and daub hut, of one of the early white settlers, still stood in a paddock. We were told all about wattle and daub and the early settlers, and it remained in my mind into adulthood, as something to be marvelled at.

The next landmark was Tally Ho Farm and Boys' Home, on the corner of Springvale Road and Burwood Road. This marked the beginning of the country as the road shrunk to a narrow strip of bitumen that ran in a straight line between orchards and paddocks to the next hill at Vermont.

It then wound its way to Upper Ferntree Gully, then a small town at the base of the Dandenongs. Our route through the Dandenongs always took us through Belgrave, Selby and Menzies Creek to Emerald. From here there were several options but the routes we took are hazy. The only clear memory for both of us is of a very lovely narrow, undulating, dirt road through the bush.

Woori Yallock Road:

Sefton Park, as The Farm was named, spanned the road. The creek flats, which were on our left as we approached the farm, ran down to the Woori Yallock Creek that flowed alongside heavily timbered hills. These were the jewel in the crown and were known as ‘the flats’. At this point we could get a glimpse of the dairy and the roof of the house. White painted fences bordered the drive and framed the gateway of the cypress-lined drive to the house. The house, dairy and sheds all sat on a small hill probably an old levee bank of the creek, so the drive sloped gently up to the house.

As we piled out of the car, the farm dogs under the cherry plum strained at their chains and yapped, and Auntie Bert and Beat could be glimpsed walking up the garden path wiping their hands on their aprons. Greetings, hugs and queries about the journey over, we adjourned to the kitchen for afternoon tea. The house was entered from the back door that opened into a wide spacious hallway from which opened the bathroom and the hallway leading to Auntie Bert’s room and the boys bedrooms. The kitchen was occupied by a very large rectangular kitchen table where most of the food preparation and meals etc took place. At the far end under a window was the kitchen sink and in the chimney opposite the door was the wood stove.

The toilet was in an unpainted wooden building down a winding path from the house. The heavy wooden door was held shut with a small rectangular block of wood which turned through ninety degrees. It was dark, smelly and spidery inside.

On a wide, flat platform facing the door was a handmade heavy circular lid, topped with a wooden handle. The bench was too high for little girls to be able to properly lift the lid, so it was wriggled sideways to reveal a deep dark chasm.

Mounting the platform and inching back so that one was seated over the fetid depths was an act of courage. I remember my legs stuck out straight in front.

Dismounting required wiggling forward and revealing once again the dark depths.

We had toilet paper in our much less terrifying outdoor dunny at home. Here, there were squares of scratchy newspaper on a string.

It was important to remember to replace the heavy circular lid, and then to wash our hands in the bathroom, just inside the farmhouse door, with a thick slab of yellow soap.

In winter of course the house was toasty warm. We all sat down to afternoon tea and ate scones with lashings of farm cream and all washed down with copious cups of tea and farm milk of course. After news was exchanged the ritual of the visit dairy to watch the milking and the pilgrimage to the pigs took place.

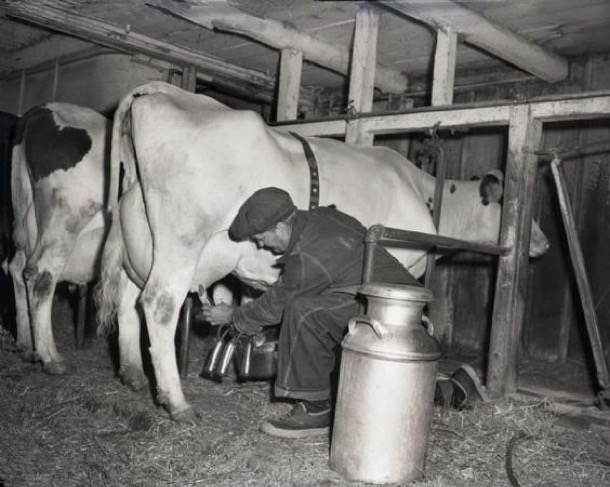

The main business of the farm was dairying. They had a herd of dairy cows: jerseys with huge liquid eyes. There were farm dogs, but the cows made their own way up to the dairy, in the late afternoon, following muddy, well trodden paths through the paddocks.

In turn they filed into the dairy, and into one of the six milking stalls, and the noisy diesel powered machine cranked up. The teats were washed with an old towel in a bucket of soapy water, a loose chain was put under the tail around the rump, and a set of shiny metal tubes was attached to each udder, with audible sucking sounds.

Each cow chewed contentedly on food in a trough at the back of the stall, as her udder, hidden by the tubes, pulsing rhythmically. Eventually she would finish, be set free and make her way out the back of the shed and another would plod in to take her place. I remember being very impressed by the way the cows seemed to know what to do.

The only glimpse of the milk itself was in a high up glass ball into which the milk pulsed as it was pumped into the room behind the dairy.

After the last cow had made her way back out to trek slowly down the hill, the clunking machine would be turned off and the clean up would begin.

Dairy farming involves the sad business of poddy calves, separated from their mothers and sold. We remember calves being fed from a bucket, but not the significance of this.

The dairy business sold cream, separated from the milk in a high tank. This used centrifugal force to collect the lighter cream and send it through a separate channel. We remember the whole milk being pumped into the tank along a wide, shallow chute.

The remaining skim milk was used on the farm to feed the pigs, Auntie Beat’s pride and joy.

The milk was mixed with some sort of grain to produce a mash, which was poured into troughs for the pigs.

Our visits always involved trekking down to the smelly pig sheds, where huge sows sloshed around or lay on their sides, in spacious, but muddy pens, surrounded by little pink and brown piglets. They also had access to the surrounding paddock: it was a far cry from modern factory pig farming, a cruel and hateful process. I can’t find in my memory any emotion connected to the actual pigs. Sue remembers cuddling the hand-reared orphan piglets in the kitchen by the slow combustion stove and the boar, who lived permanently in the muddy paddock.

We’re not sure exactly how many pigs there were, but there were about four pens, where the sows and piglets were. Possibly they were only kept in those pens when they had their piglets, and roamed in the paddock the rest of the time.

I remember Auntie Beat lifting the massive lid on some huge ground level tanks to proudly reveal a seething mass of fat maggots, her clever way of dealing with the pig excrement.

I remember our mother’s wry amusement at Auntie Beat’s enthusiasm for the pigs. Apparently she had been an elegant and sophisticated lady in her earlier life. But this version of Auntie Beat, sloshing around the pigsty in her gumboots and several layers of shapeless cardigans was all we knew.

Mostly I remember the smell!

Quite often while the grown ups were chatting we were allowed to play in the hay shed with Julie. It was such fun! The hay shed was a traditional barn shape and covered in red painted galvanised iron, peeling. Most of the painted surfaces at the farm appeared to have peeling paint. It was open on one side, so it was light and airy and a child's paradise.

Rectangular bales of hay were stacked to the roof along the back and then in descending tiers. Chooks and cats played, scratched and slept in there too. We climbed all over the bales up to the roof, built cubbies and played.

There were a few variations to this routine that I can remember. Once we went shooting on the flats with Dad and I was allowed to have a shot at a rabbit and on a few occasions we went blackberrying. We also went for a big walk up the hill over the flats. An exciting ride down to the flats in the tractor trailer and over rickety home made wooden bridge, was followed by what seemed like a big walk up the wooded hill to the top. The best adventure though, was the day we visited during hay cutting season. I can still picture it. It was a lovely clear summer day. We watched the dry, cut grass baled up into the neat rectangular bales we were familiar with in the hay shed.

Towards evening, after the milking, it was time to leave. Laden with fresh cream, milk and flowers, we made our way up the garden path to the car. After many warm hugs, we began the journey home. Often it was dark by the time we passed Emerald and it was at this point in the journey that we sometimes sang. The Ash Grove features in my (Sue’s) memory, as it was hard for me to get to the high notes. The rounds we sang were also fun and a very good activity for tired children squashed into the back seat.

‘The Farm’ visits remain in our memories as fun, and an adventure in our simple lives. It was not only because we played in hay shed and joined in the farm activities, but because we were very fond of Auntie Beat, and particularly Auntie Bert.

‘The Farm’ is still a working property today. Rob remarried, another Pat while Bert and Beat were still alive and living in the old farm house.

Rob and Pat built a new house in the front paddock, had a family, and took over the working of the farm. Tragically, Rob was killed in a tractor accident when the children were still young. Pat stayed on, running the farm, looking after the children and working part time as a nurse.

We have visited infrequently since Bert’s and Beat’s deaths, briefly making contact again when Jono and Sue kept bees in the top paddock.

This photo was taken in 1983. In the background is the old farm house. Back row from left to right: pregnant Margaret, John, Jono and Alice, our mother.

The farm is in good hands. Pat stopped the use of fertilisers in the paddocks and the dairy herd became a totally organic operation. Today one of Pat and Rob’s sons runs a very successful organic vegetable growing business, supplying top Melbourne restaurants with fresh produce. Beat and Bill would be pleased that today one of their great grandsons still works the farm.

Here is an aerial view of the farm today. The original farm buildings are in the bottom of the picture. Pat’s house is on the other side of the drive, closer to the road. Today it is surrounded with greenhouses.