The Built Environment - Box Hill

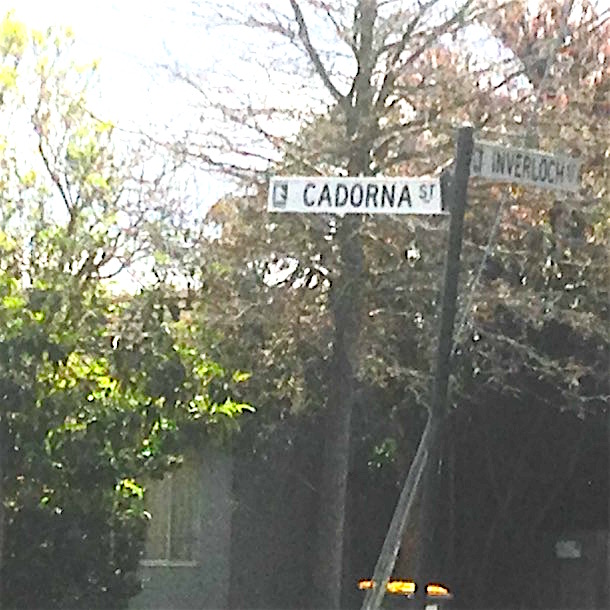

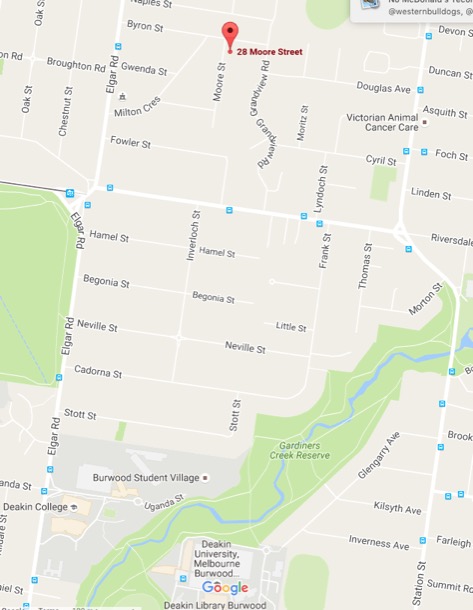

We grew up in Box Hill South in close proximity to Surrey Hills where our family has had an association for five generations. 28 Moore Street was our family home.We all spent our childhood and early adult years there, before moving out on our own. The family ventured out into Box Hill in 1946 when our parents bought a block of land in a new subdivision. They paid one hundred pounds plus ten pounds in taxes. Jim and Alice also looked further out in Donvale, where, for a fraction of the cost, they could have purchased two acres of bush. Unfortunately this was not an option as there was no public transport and we did not own a car.

After the war, Box Hill South was opened up for new housing. The City of Box Hill revised its land valuation system and residential subdivision started to boom across the municipality. The small holdings of mixed farming and orchards, were quickly replaced by the unmade road network of the subdivisions. Electricity and gas were provided, but no sewerage until the 1950’s, so it was outside toilets for all.

Our parents could not afford to have the house built, so Jim decided to build it himself. He bought a book on basic carpentry and the tools, all hand tools of course, and proceeded to build. The house is still there today, straight as a die.

It was a very liveable and rather nice design, set on stumps, weatherboard cladding and with a low slung, pitched roof. It had the standard three bedrooms ,one bathroom, kitchen, dining room, lounge room and laundry. When first built there was an outside toilet attached to the single garage that also had a chook pen attached to it.

Over time, the surrounding paddocks filled with houses and our house changed a little too. The view of the Dandenongs from the french doors in the lounge room disappeared, the toilet moved inside and our grandparents built a flat on the back. The addition of the rumpus room and flat spoilt the spaciousness of the living rooms and the back garden. The old weatherboard garage, toilet and chook pen were removed and a new double garage and new chook pen took the new additions to the back fence.

Little appears to have changed externally to the house since Mum sold it about 1981.

When we were children, Wattle Park itself consisted of large trees with mown grass underneath, like a traditional park, but with native trees and grasses. It was owned and maintained by the Tramways Board, responsible for the tram system in Melbourne. The Tramways brass band played in a rotunda every Sunday in the park. Nowadays those grasses are no longer mown. It looks much more like remnant bushland.

The 137 acres opened as a public park in 1917.

The chalet, designed and built by a Tramways architect, opened in 1928. it was promoted as a dance hall and wedding reception venue and, amazingly, it still is. It is listed on both the Heritage Victoria and National Trust Registers.

Our own parents’ wedding reception was held there in 1945, after they had been married at the Wyclif Surrey Hills Congregationalist Church in Surrey Hills.

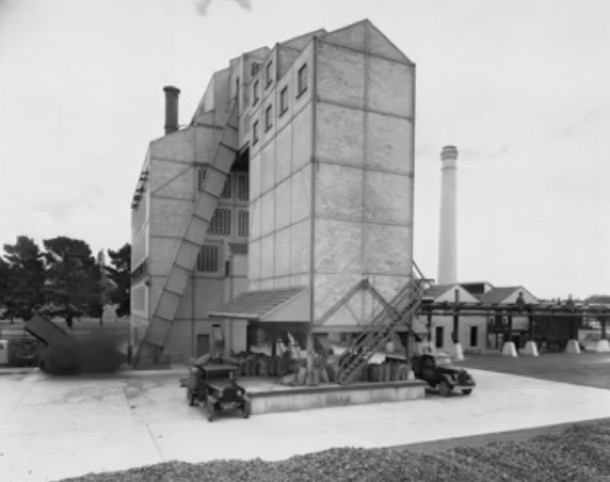

Box Hill Gasworks is now gone, but it was an important part of our parents' history. It was built early in the history of Box Hill:

7/1/1890 The Argus

Some twelve months ago the Nunawading and Boroondara councils granted permission to Mr. Thomas Coates, hydraulic engineer, to lay down gas mains in the streets of the two shires. Mr. Coates purchased an eligible site near Elgar road, Box Hill, upon which to erect the gasometer and the other necessary buildings. At the present time all the mains have been laid down in the shires named, and Mr. Coates is now in a position to light up Surrey Hills and Box Hill with gas. The local works are of such a nature that Mr. Coates contemplates being able to supply the wants of the district for many years to come without enlarging the gasworks. Last night a trial was made in Box Hill and Surrey Hills, when the corporation lamps were lit with gas for the first time. Illumination works were erected at the intersection of the leading streets. The trial was considered a very favourable one, the gas burning bright and clear. In connection with the lighting of these shires with gas a public banquet will be held in Surrey Hills next Monday night.

Over time three gasometers were built.

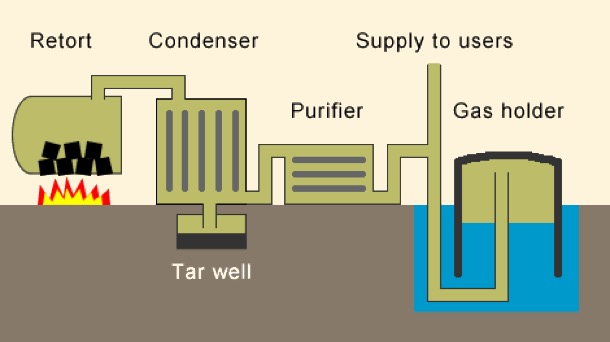

We don't know exactly when Jim started work at the Box Hill Gasworks, but in 1945 he left the Maribinong Munitions factory, where he had spent the war years. It was that year when our parents married and Jim moved into his in-laws’ Surrey Hills house. Soon after, he started work at the gas works as an analytical chemist. He worked there until began teaching in 1954.

Sue remembers him riding his bicycle to work, and later, a motorbike.

He worked in the laboratory, doing things like checking the calorific value of the gas.

Melbourne’s gas supply was made from Latrobe Valley brown coal, sent by rail to the various gasworks, owned by Colonial Gas Company. Box Hill was one of the biggest. As Melbourne expanded after the war, the demand for gas meant that the various gas works were very busy.

But, by 1960, substantial natural gas reserves had been discovered around Australia. Over the next five years all the Gas plants in Melbourne had closed down, and over 1000 workers were made redundant, by the discovery of natural gas deposit in Bass Strait. Over one million gas appliances in Melbourne were converted to natural gas in 1968. We remember the conversion time. There must have been plenty of publicity. Natural gas has no smell, and, for safety, they put in an additive to make it smell quite strongly. The flame was slightly different, but all the existing burners still worked.

The Gas Works are long gone. Box Hill Institute now occupies the site.

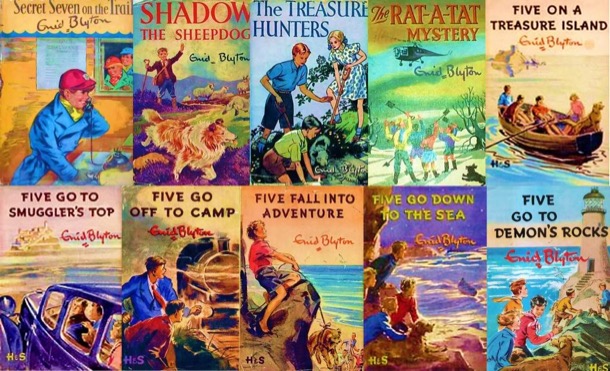

One of the fortnightly highlights in our simple lives was a trip to Box Hill Library. We loved this excursion, as we spent many hours reading on our beds. Books were expensive and we only owned a few. We had to rely on the Library so that we could finish our favourite series like Famous Five and the Billabong Books.It was very exciting if the next book in the series was on the shelf.

This small brick building was opposite the Town Hall at the end of the shopping centre. Whitehorse Road always had a wide, tree lined median strip, as it does today, and the library was right in the middle. It was later replaced by a grand modern library, but the small brick building is still there.

In our childhood, a trip to Box Hill shopping centre was quite an excursion, involving a four mile walk. In 2019 Google Maps says it takes thirty two minutes, but with small legs and a pusher as well, maybe it took a little longer. I remember it was fun and not arduous at all. The route went through suburban streets until Canterbury Road and from there it was ovals and open ground.

Box Hill Brickworks was one of the best sights on the walk to Box Hill, as the brickworks were still in full production. We marvelled at how small the men and carts were at the bottom of the quarry, and watched the procession of carts pass up and down the steep rail track to the actual brick works.

Box Hill Brickworks was founded in 1884 and was one of fifty or so brickworks throughout Melbourne, producing bricks, tiles and pipes for the building boom and ever expanding city. During the working life of the brickworks the clay was extracted from two clay holes or quarries. The first became Surrey Dive which became a popular swimming venue, but off limits to us. Sometimes however, we also gave ourselves the horrors, looking at green, mysterious waters. There were rumours of 'the dive' being bottomless and of swimmers disappearing in its murky depths. One story was of a man who took a very deep dive off the cliff side and simply disappeared. Some time later his body surfaced in Blackburn Lake, five kilometres away. No wonder we looked in awe and horror through the fence.

Today Surrey Dive is an attractive small urban lake used for swimming and remote controlled boat races.. A walking track around the ‘old dive’ and the brick works is planted with indigenous vegetation and a relaxing and attractive area.

The other clay hole was the quarry that was in operation doing our childhood. It was adjacent to the brickworks and kiln, now derelict but still heritage listed. Unfortunately no restoration work has been carried out. The kiln itself was a massive, red brick building constructed on two levels and, of course, with a huge brick chimney.

The quarry that was still in full production in our childhood, is now completely filled in. That cavernous hole in the ground is now a large mound covered in every weed known to man. On the horizon above the weeds, are the sky scrapers of twenty-first century Box Hill.

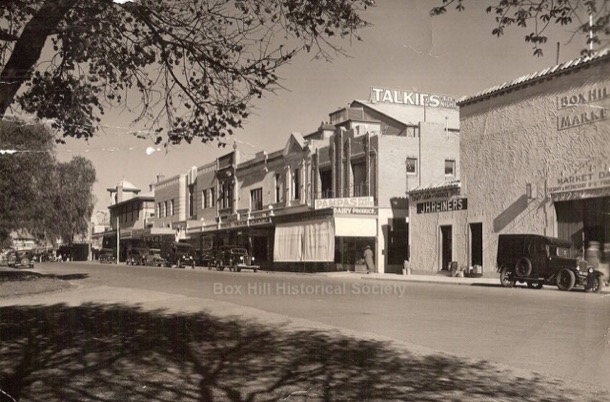

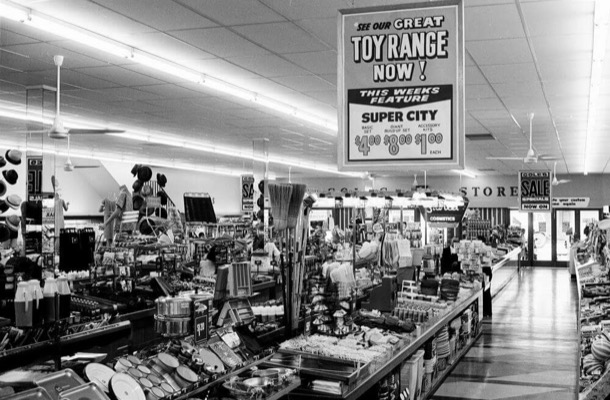

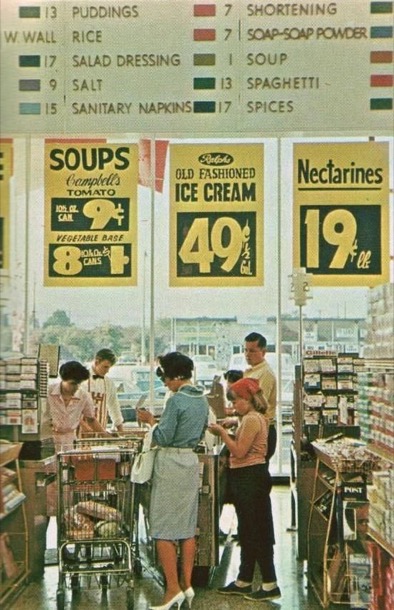

Box Hill shopping centre developed as a commercial centre, as soon as the railway line between Hawthorn and Lilydale was finished in 1862. It became an important transport hub for the eastern suburbs and beyond. During our childhood, Box Hill was the shopping destination for a big purchases. For instance, I can remember choosing a ‘walking’ doll with opening and closing eyes for a birthday present and the excitement of choosing a winter coat with a brown velvet collar. Another favourite shop was the delicatessen where such delicacies as rollmops, sauerkraut and frankfurters could be bought. Amongst the many single fronted small businesses were several large shops such as Taits haberdashery on the corner of Whitehorse Road and Station Street and Maples furniture shop. We also had a Coles variety store that sold anything from socks and singles to cosmetics, and MacEwans Hardware whose slogan was, “You can do it with McEwans because we’ve got a million things.”

This is a photograph of Box Hill Station and the surrounding shopping precinct in the 1960s. In the centre of the photograph is the old station, that is now underground. Today, above ground, occupying the whole block surrounding the old station, is Box Hill Central and surrounding shopping malls. The signal box, the tall structure on the left of the railway gates is now occupied by the thirty-six storey golden residential tower, called Sky-One.

In the twenty-first century, Box Hill, as a commercial centre and transport hub, continues to influence the built environment around it, as you have no doubt witnessed. Officially designated as a development hub, Box Hill now sports high rise office and apartment towers. The streets we once drove down are now shopping malls, the station is underground, the railway gates are long gone and the strip shops have been replaced by a multi storey modern shopping centre. When we were children the shopping crowds were white and Anglo-Saxon. Today they are predominately Asian and the shops and restaurants reflect the change in population.

When we, as a family, first started going to the local Presbyterian church, it was called Presbyterian, Wattle Park. We had PWP embroidered on the front of our blue gym uniforms. This was before the advent of the Uniting Church. Church services were held in a cream brick building, called Forsythe Hall.

Attached, behind it, was an older little wooden building. During our childhood, this wooden building, Staley Hall, was used for a kindergarten during weekdays. In the evenings, various groups used it, including church boys’ and girls’ clubs (PBA and PGA) and the mixed club (PFA- Presbyterian Fellowship Association), we went to as teenagers. Sue and I both learnt to dance there, and I broke my front teeth on the heater in that room.

We have many memories of Forsyth Hall… dances, performances, Saturday afternoon movies, gym classes and, of course church services.

Both our parents were Elders of the church. Our mother taught Sunday School, our father ran the PFA for a while, and was on the board of management. The church was their only real friendship group, and was the only social life we had, as a family.

In the early 1960s the church community began the project of building a new church on the site. The size and scale of the project was a source of much disagreement between our father and others on the management committee.

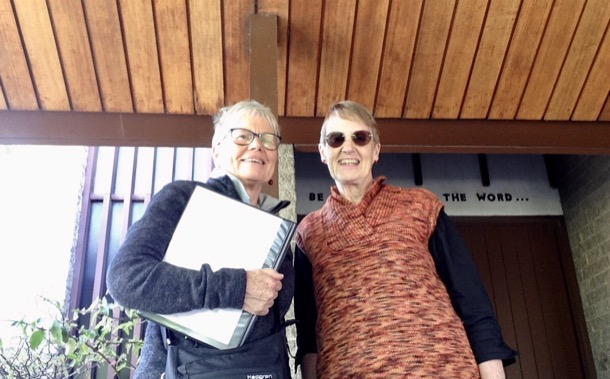

In the end, a very grand architect designed building was commissioned. The new building was designed by well known architects Chandler & Patrick. An 1887 pipe organ was relocated from a church in Melbourne and extensively rebuilt. The new church, renamed St James, opened in 1965.

I loved it, because I sang in the church choir, and it had a choir loft at the back and great acoustics.

The buildings are still there. Sue and I visited as a detour on our “back to school” walk in 2016.

Auntie Bert, a "sterling character"

These three young women are our grandmother Alfreda on the left, with her two younger sisters, Beatrice in the middle and Berta on the right.

Alfreda’s set jaw and determined look reflect her independence and demand for an education. I fancy I can see both the rebel and the farmer in Beatrice’s broad face. But look at the gentle, faraway, passive prettiness of Berta. What experiences are already clouding her young face?

About ten percent of the whole of Australia’a population, the country’s young, fit men, set off to war in 1914. More than half of them were killed, gassed, wounded or taken prisoner. There was no such diagnosis as “post traumatic stress”, but we can extrapolate from the modern experience of returning soldiers.

What happened to the equivalent ten percent of young women, who, in different circumstances, would have been marrying them and having their babies?

Our Auntie Bert became one of the many “maiden aunts” of that very specific generation. The family lore is that she “had opportunities” to marry but “chose to stay in the bosom of her family”. We do not know what the reality of her young life was. Had she been a boy, she would have been one of the 417,000 men who enlisted. One would presume that virtually all the young men she might have had a romantic interest in… brothers of her friends, boys from church, at work, on the train, in her neighbourhood… nearly all would have been absent for four years from when she was 18 until she was 22.

Berta Holm was born in 1896. Her childhood and early adult life was spent in St Kilda.

The family story is that Berta and Beatrice unlike their older sister, Alfreda, did not hunger for an education.

Alice and Marge said this in quite a disapproving tone, which made us wonder about the accuracy of the statement, that Auntie Bert left school at Grade 4, declaring that she would prefer to help her mother at home. In Grade 4 she would have been nine or ten!

At the time Victoria was a progressive state and proud to be the first Australian state to create a system of free, secular and compulsory education. This legislation introduced in 1872, required all children aged 6-15 years to attend school unless they had a reasonable excuse. Schools were built, and a system of inspectors employed to enforce compulsory education. Fines for non-attendance were five shillings and increased for further offences. Did Auntie Bert leave school at the tender age of nine or ten? We think it more likely that she attended a State school, maybe unwillingly and, after trying a private school for young ladies, left at the age fifteen. Their disapproval of the lack of enthusiasm for education, compared to their own mother’s, probably colours the story about their aunt. The view of Auntie Bert we were brought up with, was that she was good with her hands, but, to soften and elevate this statement in true Holm fashion, it was followed by, she was a superb craftswoman and much in demand: not academic but exceptional.

Some time after she left school Berta went to work in Flinders Lane.

At that time Flinders Lane was the centre of the ‘rag trade’ where many Jewish firms had their businesses. Amongst them was Slutskins, for whom both Berta and Beatrice worked doing ‘white work’. Whitework embroidery is the general term for hand embroidery worked with white threads on white fabrics. It is one of the most elegant and timeless styles of embroidery and was used on underwear, night gowns, table linen, handkerchiefs, baby bonnets, christening gowns and many other small items.

After some experience in this area Berta became forewoman, in charge of a group of other women.

We only have Alice and Marge’s childhood recollections from which to piece together Berta’s life.

In early 1925, when she was twenty-nine, perhaps moving away from her parents’ home for the first time, she left her job, probably that responsible position as forewoman. She went, for an unspecified time, to the country, to help her married sister with a toddler and a baby, and to help serve in her brother in law’s hardware shop.

Alfreda had given birth to Alice, our mother, in 1923. She had had a terrible time, alone, during her first delivery, resulting in the death of the baby. We don't know anything about Marge’s birth or the subsequent few years, except that they were quite near to family help. But when Alice was fifteen months old, Alf and Alfreda moved to Bacchus Marsh. Alfreda was “weak from the birth”. The descriptions of her crying, while scrubbing the floor and having to spend whole days in bed, apparently requiring the help of her unmarried sister, makes us think of post natal depression.

Alf too had what we would today call “mental health issues”. He was a gentle, quite scholarly person, and the business venture in Bacchus Marsh, on the eve of the Great Depression, took a toll on his health. It is no wonder Marge and Alice remember Auntie Bert as a tower of strength and support.

In 1928, the old dry house they had been living in caught fire. At the top of the burning staircase were the little girls in their nighties, Alf sedated, because he was in the midst of a “nervous breakdown”, Alfreda, reportedly trying to find her stockings, and Bert, who carried Alice down the stairs. Marge was carried down by her father, finally awake.

The destitute family were taken in by “the Pierces”. Nell Pierce was a lifelong friend of Auntie Bert. Did they meet there at Bacchus Marsh? We don't know.

The family stayed on for at least a year in Bacchus Marsh, but Berta moved back to Melbourne, once again moving in with her parents, probably her only option.

Now in her early thirties and unmarried Berta must have turned her attention to a job. As far as we know this is when she decided to start her own business as a dressmaker. At first she worked from her bedroom, building her business and reputation.

The business was eventually profitable enough to allow her to move to premises in Riversdale Road, Middle Camberwell and then to Burke Road in Camberwell, just over the junction.

I can remember the junction premises quite vividly. It was one big room on the first floor. Big windows looked out onto Burke Road, letting in light and sunshine that fell on the big work tables. Several dressmakers dummies stood in the corner where the fitting room was screened by curtains. It seemed a very busy place.

The big tables, that dominated the space were covered in the paraphernalia of dressmaking. There were several sewing machines, many reels of sewing cotton, several pairs of big dressmakers shears, other dressmaking scissors and many tins of pins. Rolls of fabric and garments in various stages of construction took up the rest of the table space. Another woman was sewing at the table, presumably an employee, so business must have been good. We were probably there for a fitting, as Auntie Bert made ‘good clothes’, for Mum. These beautifully tailored clothes were worn to Church and were for special occasions, including weddings:

She also made us beautiful clothes including these woollen dresses:

Auntie Bert had an account at Ball & Welch, a prominent department store in Finders Street, Melbourne. She needed an account for her business and a reliable source of good quality fabric for her clients. Its four floors occupied one third of the total block and stretched between Flinders Street and Flinders Lane.

Its many departments included gloves, umbrellas and handkerchiefs, fabrics, furniture, china, millinery, furs and corsets. At one time twenty-six assistants were devoted to the sale of lace alone.

Members of the family were generously given access to Auntie Bert’s account, making it possible to buy items on account and pay later. This was very useful at times, as there was no such thing as Credit Cards. At the end of the month, Auntie Bert sent out letters to all those who had used the account, and we reimbursed her by cheque. This was probably quite a task, not only the arithmetic, but also the sending out of all the individual letters.

I can remember enjoying trips to Ball&Welch. The lifts were staffed by attendants in uniform who recited the list of items available at each level as the lift rose between floors. Parcels were wrapped up in brown paper and string, on huge wooden counters. The expert shop assistants were reserved, formal and a little forbidding to a young child. The exchange of payment was quite a process. The shop assistants' job was to serve the customers, not handle the money. When payment was made, it was placed, with the hand written docket, in a metal canister that went shooting on wires across the departments and then upstairs to the Accounts Department. The docket was checked, change inserted, a receipt written and the canister whizzed back from whence it had come. Transaction complete.

The cash-ball system worked reasonably well, but the rails were intrusive and the interior layout of some stores did not allow certain counters or departments to be connected by inclined tracks. The ingenious Lamson then hit upon the concept of the “aerial railway” and set about tinkering with a gondola-like design, which became known as the wire-line or cable-carrier.

By the late 1880s, sales staff could secure cash inside a small wooden jar or canister, suspended by wheels from a taut wire that ran overhead from the sales desk to the cashier’s station, which was typically a cage-like booth situated in the center of the store. By tugging firmly on a spring-loaded cord or lever known as the “propulsion,” the canister would be catapulted along the wire, reaching its destination in mere seconds.

The cashier could then “return fire” with change and a receipt. Cashiers who worked in booths on levels above the sales floor could simply release the canister and let gravity return it to the appropriate counter.

Ball and Welch closed its doors in 1970, the end of an era .

Berta’s sister, Beatrice had taken up dairy farming in the early 1950s, near Cockatoo, in the Dandenong Ranges. The bulk of the work was done by her husband, and three sons. In 1955, the wife of Rob, the middle son, died, leaving a baby daughter, Julie, to be raised by her grandmother.

Into the breach stepped Berta. She moved into a small bedroom in the farm house, and became a second mother to Julie. We remember her room. It had been part of the farmhouse verandah, and the whole room was about twice the size of the single bed. It was neat, sparse and dark.

Our memory of Auntie Bert at the farm is solely inside the farm house. Unlike Auntie Beat, who mucked out the pigs, wearing layers of old jumpers and a woollen beanie, Auntie Bert was always nicely dressed. We remember her in well-cut woollen skirts, stockings and heeled court shoes, with classy jumpers and cardigans. We picture the two of them in the kitchen, both wearing aprons, turning out scones and cakes on the wood stove. Auntie Bert became a permanent and valuable member of the family, looking after the “boys” and Julie.

While her main home and focus was life at the farm, Auntie Bert continued, as she had her whole life, to be the family helper and nurse. She had looked after both her own parents in their final years, and she came to live with us to help out with her elder sister: our Nana, Alfreda, who had dementia. We remember her as a quiet unobtrusive presence in our home. A few years later she came again and helped with Alf, our grandfather, in his final weeks.

So Alice saw first hand, the skill and care of Berta’s nursing:

Apart from staying temporarily with other members of the family, usually to help out during family crises, Berta lived there at the farm, until her death in 1976, aged 80.

Alice reflected on Berta’s death and the simple generous life she lived:

From left to right, Nana, Auntie Bert and Alice:

Decade by Decade

Here is the audio of this from the recordings:

With our more modern education, we have less of a firm grasp of History, and we know that our children, and their children have, and will have, an even sparser knowledge. So we have taken the overview concept, explained a little more fully, and added in our father’s family history and other aspects we have recently discovered.

Alice and Marge finished recounting their family stories at 1950. One of our tasks in this project has been to continue on from then, and so we have done just that. We explore the nineteen fifties, sixties and seventies, linking what was happening in the wider world into our own lives.

1850-1950

Between 1839 and 1872 our ancestors arrived in Australia.They came from both Northern and Southern Ireland, England, Germany and Denmark. All were from humble origins, having worked as agricultural labourers, domestic servants, a baker and an engineer. Some were already married and others met here.

As our ancestors built their new lives in Victoria, the First Australians had already felt the disastrous impact of European contact. There had been violent conflict, the Wurundjeri population had been decimated and the survivors relocated to reserves or camps a ‘suitable' distance away from the growing population of Melbourne and outlying settlements. In 1844, when the Bourkes took up their selection at Pakenham, they were the first white settlers in the area and the “blacks camp” by the river was noted in Catherine’s memoir. Several years later, Adam Rye, from the other side of the family, was robbed by a party of ’50 blacks’. The newspaper report notes that ‘the blacks at this time were very treacherous’.

With the discovery of gold, in New South Wales and Victoria, there was a huge increase in population and in wealth.

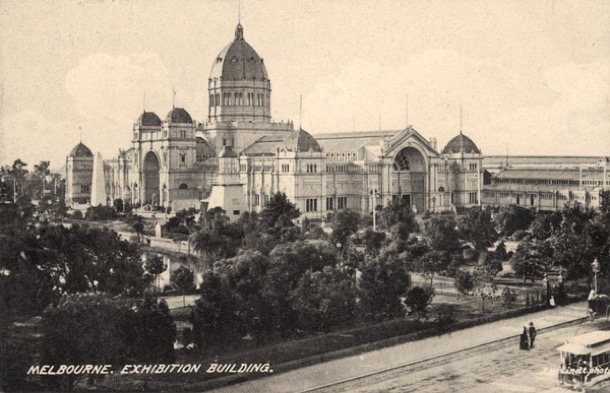

Victoria benefitted the most. Melbourne became Australia’s largest city, with a huge land boom. Grand old buildings like the Melbourne town hall and exhibition buildings are reminders of those glory days.

The increase in population, rapid development and the attraction of the goldfields led to a shortage of workers. This meant great job opportunities at every level. It also put workers in a good bargaining position.Trade Unions developed and working conditions were the best in the world. Australia was an egalitarian workers’ paradise.

Small businessmen, like publicans, bakers and lawyers, prospered with the growth in Melbourne. For farmers, it meant bigger markets, more mouths to feed. The growth in country towns, better roads and railway development made life in the country less difficult.

Engineers had a lot of work with the sudden development of infrastructure and property developers were run off their feet. Our grandfather’s grandfather, a young engineer from England, was building bridges in the expanding colony. While building the bridge across the Barwon River, his son, our grandfather’s father, was born, his birth unregistered.

Back in ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ our grandmother’s grandparents who had arrived from Belfast, were developing St Kilda: building large houses and public buildings for those who were prospering in the boom town.

On the land, our maternal ancestor Adam Rye, who had survived the attack by ’50 blacks’, settled in Geelong and worked as a farm labourer. He was later gripped by gold fever and went north to seek his fortune, only to be held up by bushrangers and lose his meagre pickings. His daughter married a German immigrant, Dau, and they settled on a mixed farm at Wandong. Here they raised seventeen children and supplied food to the growing population.

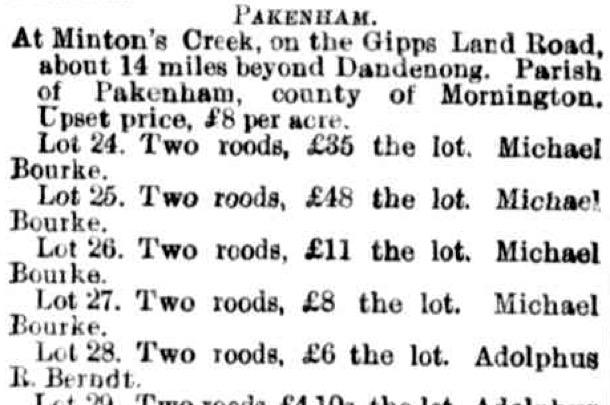

Meanwhile our paternal forbears, also on the land, were making their mark in Gippsland and North Central Victoria. In Pakenham the Irish Bourkes were building their family of thirteen children, and now owned Bourke’s Hotel. They were becoming significant landowners and community members, as they set about acquiring land, marrying their daughters well and establishing their sons on large and prosperous properties. They also served their community in local Government and built the horse racing industry in Pakenham.

1858 Land Sales, Michael Bourke's purchases:

The MacCormacks, in North Central Victoria were also acquiring and working large grazing properties, firstly in Tallarook and then in Molesworth. They too were pillars of the local Catholic Church and community. Our grandmother was born there, at Balham Hill, pictured below.

Melbourne became the financial centre of Australia and New Zealand. The Pakenham Bourkes’ fourth son, our great grandfather, was part of this world. He had moved to Parkville and built his law career in this thriving city. Australians were growing in confidence and the young nation was showing signs of an interest in its own identity. This was the era of Henry Lawson and Banjo Patterson, who wrote about the characters of ‘the bush’. At the same time, Tom Roberts and his paintings glorified the unique Australian landscape and the men and women who toiled there. This growing sense of identity and of nationhood is reflected in the moves for independence from Great Britain. During this era of optimism and hope our grandparents were small children, and their families were well established in both country Victoria and Melbourne.

Federation was achieved in 1901, and the country celebrated:

Australia was longer a colony but an independent nation. Melbourne was the largest city in Australia at the time and the second largest city in the Empire (after London). It was fitting that the new Parliament should sit in Melbourne while Canberra was being constructed.

The decade after Federation saw Australian women join the battle for women’s suffrage. White men over 18 in Victoria had had the right to vote since 1858, but women were not granted this right until 1908. Our maternal grandmother, Alfreda, was sixteen when women were granted the right to vote. We imagine she would have approved. She had been engaged in her own battle to pursue her dream of further education; and during this decade she finished her secondary education at Melbourne’s Continuation School, the opening of which marked the beginning of state secondary education in Victoria.

This period of prosperity, optimism, and political and social change ended in the devastation of the Word War 1. We know little of the family’s war service, but three of our maternal grandfather’s uncles served in France, and one lost his life. In the highly charged patriotic atmosphere of the time, and with mounting casualty lists, the war years must have been a difficult time, especially for our grandfather who was considered unfit for service due to ill health. He was deeply upset when given a white feather. Presumably our paternal grandfather being a country doctor, was in a protected occupation.

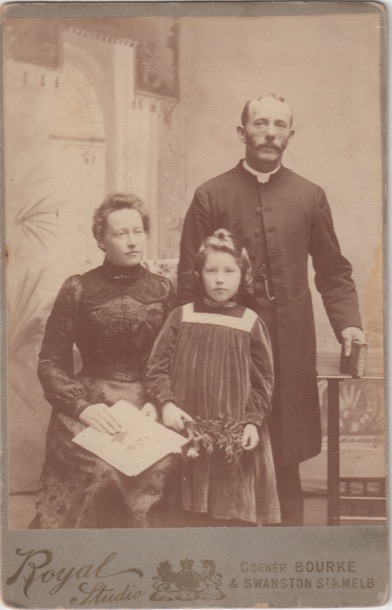

Our grandparents were all married at the end of this war. Our father’s parents were married in St Patricks Cathedral in a grand affair. Grace and Hugh then settled in Koroit in the Western District, where Hugh was the local doctor.

In contrast our mother’s parents were married in the Methodist Church in Surrey Hills in a small and simple ceremony where the bride did not even wear a wedding dress. At that time Alfreda was working as a teacher and Alf was working in a hardware shop in the city. They also moved to the country, soon after: to Eildon, where hardware supplies were needed for the construction of Eildon Weir.

Our family then lived through the Great Depression of the thirties, formative years for our parents who were by then at school. Our father was boarding at Xavier College and our mother was at Croydon Primary School. By the end of the decade the world was at war again.

During the war in a munitions factory, in Maribyrnong, two very different family histories were to merge into one. One was Irish Catholic, successful and quite wealthy, and the other was staunchly Protestant and relatively poor. One was involved in the Melbourne horse racing scene and the other was teetotal and interested in ideas and the new ‘isms’ that were emerging on the other side of the world. Our parents were married at the end of World War 2.

1950s

Our mother’s view of the 1950s, in her recording, is of a time of burgeoning economic growth and development. To us, it is the decade we first became aware of the world.

Our world was redolent with Australiana, but we were intensely aware of our British heritage, and it dominated our reading, our schooling, our whole culture. A portrait of The Queen hung in our school. Sue remembers keeping a scrap book at home of magazine articles about the Royal Family. She was particularly interested in the corgis. Apparently I had one too, and it contained very many pieces about Princess Margaret.

Enid Blyton Books:

Globally, it was a dangerous world, with the cold war in full swing, and a very real threat of nuclear war. Our parents had quite well developed political opinions, particularly our mother, so we were exposed to adult conversations about the issues of the day. Family friends and neighbours, the Lees, were active in the union movement. They encouraged our parents’ involvement in the movement for “unilateral disarmament” and other left wing activities. I remember our mother’s admiration for an older couple who took a small boat out into the Pacific Ocean to protest the nuclear testing. Bikini Atoll in the Pacific, sixty years on, is still a no go zone from the USA nuclear tests carried out there up until 1958.

This was the time of McCarthyism in America, and Australian political attempts to ban the Australian Communist Party: a divisive time, where everyday people had strong opinions one way or the other. Sue remembers Prime Minister Menzies as “the devil incarnate”.

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament became overwhelmed in the 1960s by anti Vietnam War action, but it was an important political movement of the 1950s. The familiar “Ban the Bomb”, or “Peace” symbol was invented in 1958, as a symbolic representation of ND (Nuclear Disarmament)

Our family was, by today’s standards, quite poor, but this did not impinge on our life, at this time. We were well fed, we had a stay at home mother who looked after us and the struggle to pay bills was not part of our conscious experience. As far as we children knew, we were neither poorer nor better off than our neighbours, with the exception of the family in the housing commission house nearby, whose son had polio and who didn’t always have enough to eat. The world, as we observed it in our daily life, was largely classless. Perhaps Australia at this time really was the egalitarian workers’ paradise it purported to be, to prospective migrants in Britain. (only whites of course)

Nevertheless, we knew about the religious and economic differences within our family: that our father’s relatives were wealthy and that we were not, because our parents’ union was a “mixed marriage” and very disapproved of. We were very aware of their Catholicism and our Protestantism, and that we were not as close to our grandmother as our cousins were.

Our father during the 1950s, went from working as an industrial chemist by day, and studying by night, to full time teaching. We got our first car, a television and a refrigerator. By the end of the decade there had been four children born. It was busy, but simple life, encumbered by very little “stuff”.

Our suburb of Box Hill South was the edge of suburbia, when our parents first bought their block. During the fifties the new suburbs filled in with more and more families, and the frontier stretched east towards the orchards of Blackburn.

Below is Doncaster, contrasting the 1945 view to that of today. It was little changed in the 1950s. We remember breaking an axle on our Talbot car in Doncaster, a farming and orchards area with narrow unmade roads.

The sewerage reached us during the late fifties. Neighbours got together to dig each others’ trenches. The footpaths were paved, allowing us to roller-skate along them.

The streets were deemed to be safe enough for five year old girls to walk unsupervised, from Box Hill South to Surrey Hills to Sunday School and to Bennettswood to school.

We are baby boomers, and this was the most booming time. When we began school, Sue in 1954 and me in 1957, “temporary” schools were being thrown up, and unqualified teachers recruited to deal with the rush.

My first experience of school was a few weeks in “bubs”, and then the-bursting-at-the-seams class was reduced by a handful of us being put straight into Grade 1. Here is that grade photo with Miss Meadows and her 47 pupils.

1960s

This decade covers our teenage years. It was a time of huge change in the western world. By the end of the decade, Neil Armstrong had walked on the moon, women were controlling their own fertility with the Pill and popular culture had discovered the huge Baby Boomer teens market. During the sixties, there was a general loosening and questioning of traditional social norms. Older people were probably more aware of these momentous changes. For us the loosening of the cultural apron strings, that is such a feature of these times, coincided with the loosening of our familial apron strings.

The conflict between our generation’s straining at the bit and society’s entrenched traditional values played out in our school life. As fashion hemlines rose, school uniform strictures fought them. We knelt to have the gap between our uniforms and the floor measured precisely, and hastily pulled down our hoiked up dresses whenever a teacher came in sight. The anti war slogans on our pencil cases, alongside the names of pop groups we fancied, had to be kept hidden, or there would be detention. A new rule dividing the grassed hill area into a boys’ side and a girls’ side transformed the hill into a vast empty space with a cramped central area where everybody sat alongside the invisible line. In our school, as far as we can remember, there were no brown faces, hardly any Asian faces and no Aborigines. Foreigners were the Italian and Greek “new Australians”, and even they were rare in our (then) outer Eastern suburb.

Culturally, as more and more families spent more and more time around the television set, American culture rather than English, began to dominate our life.

We can’t remember exactly when we got a television set, just that it was bought specifically for watching cricket. As a family we watched the Australian serial Bellbird, which preceded the seven o'clock news. There were a succession of American sit coms we all watched, like My Favourite Martian, Bewitched, Father Knows Best, the Donna Reed show, Bachelor Father, My Three Sons and Mr Ed. After school I remember Clutch Cargo, Sea Hunt, George Reeves in Superman, and Hogan’s Heroes, F troop and Bonanza. And very rarely we were granted permission to watch 77 Sunset Strip. These are nearly all American titles. There were Australian and English shows too, but it is the American ones we remember.

With this American influence in our lives, and increasing prosperity, “teenagers”, a term first heard in the 1950s, emerged even more as a marketing target. For the first time, teenagers had their own music, fashion, language. I was more plugged into Teen culture than Sue. I began to go to local Saturday night church dances from about aged 14. There was always a live band who played rock and roll covers. A group of us from church would go.

Dress was quite formal, ties for boys and stockings and heels for girls. I remember the winter that plain coloured wool dresses with white crocheted collars and cuffs were all the rage: probably 1965. Auntie Bert, dressmaker to the wealthy ladies of Melbourne, made me a tailored aqua one with little kick pleats around the bottom.

Below is fourteen year old Margaret in the aqua wooden dress with while crocheted collar and cuffs.

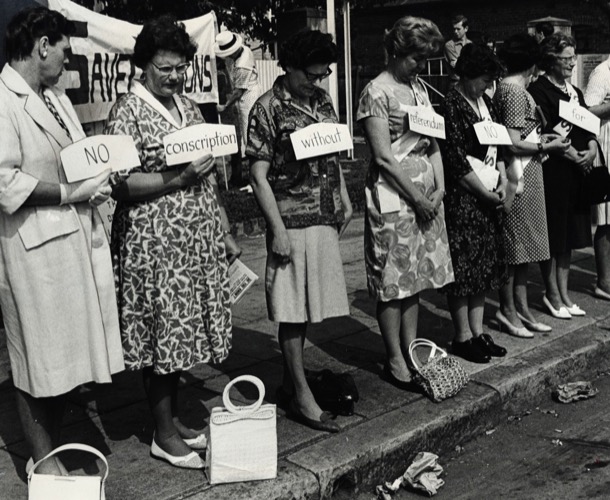

During the 1960s, Australians were entrenched in the divisive Vietnam war. Our family was by default anti war, and the “all the way with LBJ” policy of our government was fiercely criticised. In 1967, my boyfriend and another close family friend was conscripted for military service. Against huge opposition, the government had voted to call up into military service some twenty year old men. Many of them ended up fighting in the jungles of Vietnam. Our mother testified in court for the other friend, who was a registered conscientious objector. But many other friends and acquaintances went off to Vietnam with their hair shaved and very basic training. Some of those veterans live with the trauma of those experiences even today.

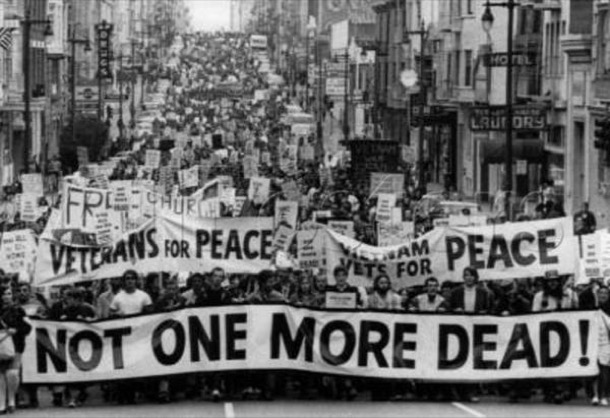

A "Save Our Sons" movement protested against conscription:

Gradually, public opinion in Australia, as in America, swung firmly against the war; and ordinary Australians demonstrated in the street.

By 1970, Sue and I had left school and were engaged in our tertiary studies, sharing a house in North Balwyn. University was still expensive, and we both managed it by gaining a bonded scholarship called a Studentship, which paid our fees, as well as a small living allowance. Even in a relatively enlightened family like ours, it was made clear that any family budget that was to be spent on university studies, was to be saved for our younger brothers, because they were boys.

1970s

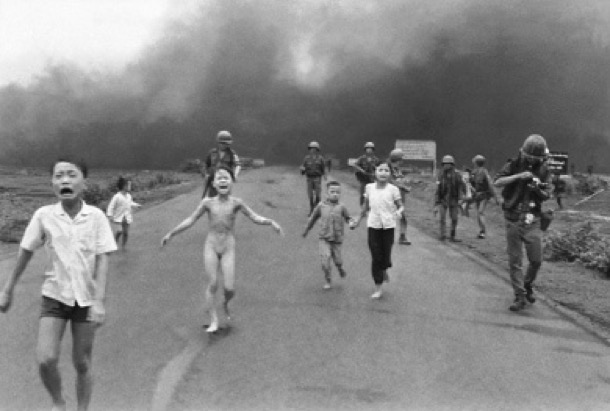

The 1970s was a decade of change for us personally, and a tumultuous time worldwide. In some ways, the decade was a continuation of the 1960s. Women, gays and lesbians and other marginalised people continued their fight for equality, and many Australians joined the world wide protest against the ongoing war in Vietnam. Outrage at the continuing conflict was fuelled by the graphic coverage of the brutality of war, available nightly on our TV screens.

Protest was bitter and violent.

By 1975 Saigon had fallen: a humiliating defeat for the USA.

There was more violence as Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge murdered 1.7 million Cambodians, and on the other side of the world, the IRA fought for British withdrawal from Northern Ireland.

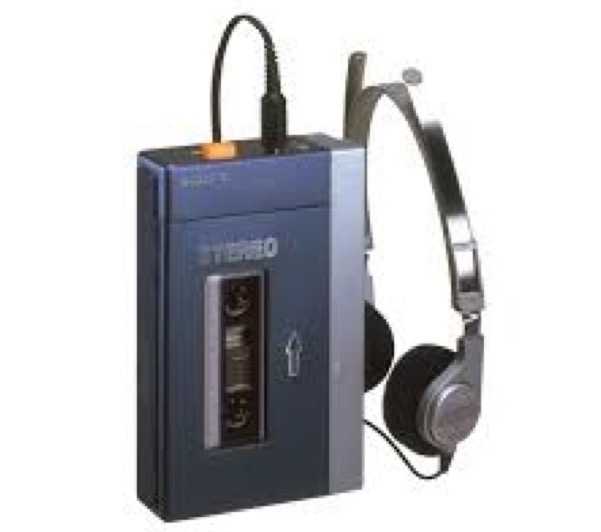

Rapid advances in technology were in play, changing our world and planting the seeds for the creation of digital world, we are grappling with today. Apple launched the Apple 1, a desk top computer, pocket calculators were commercially available for the first time, and music became mobile with the release of the Sony Walkman.

In the popular music scene, Elvis Presley died, the Beatles split up, the Sex Pistols band recorded an album and disco music took the world by storm.

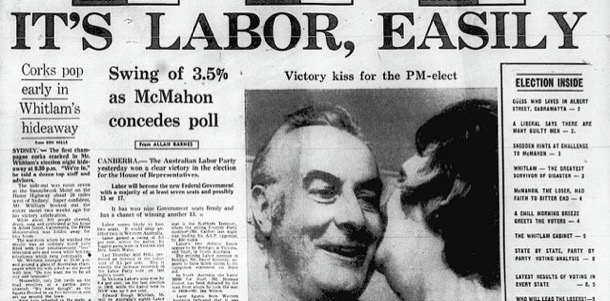

In Australia, at the beginning of the decade, Gough Whitlam led the Labour Party to victory in the 1972 election. This ended twenty-three years of unbroken Liberal-Country Party Coalition government.

Change was inevitable and rapid: the troops were brought home from Vietnam; educational reforms were introduced, such as free University education; and Whitlam visited the feared red menace, Communist China. Inept financial management, scandal and the rate of change contributed to another landmark event now known as, The Dismissal. Whitlam was sacked by Kerr, then Governor General.

Gough Whitlam stood on the steps of Parliament House and declared “Well may we say ‘God save the Queen’, because nothing will save the Governor- General”:

The Liberals returned to power under Malcolm Fraser. For Labour supporters like us, it was a bitter pill.

Waiting in the wings was Bob Hawke, who was both President of the ACTU and President of the Labour Party. The 1970s ended with Hawke deciding to enter politics. He was elected as the member for Wills in the 1980 election and Labour was once again in power. The 1980s in Australia was Hawke’s and Paul Keating’s decade. The reforms they ushered in changed the face of Australia: we thought for the better.

At the beginning of this tumultuous decade Margaret and I were fancy free. We moved out of home, sharing a house and living on our teaching studentships, as university education was not yet free. Margaret supplemented her income, paid $1 an hour, working at the first fast food outlet in Bourke Street. Working the late shift posed no danger as the Derby closed about 11 pm [very late] and Margaret was able to walk out to her Morris Minor parked right outside the restaurant. “It was always easy to park in Bourke Street, there were lots of parking spots,” remembers Margaret. It was such a different city then. We also embarked on our teaching careers. I began my teaching career in Sale and Margaret at Moe.

We had wonderful camping holidays, often in the Snowy Mountains; we saw interesting alternative movies at the Walhalla picture theatre in Richmond; we went to Sydney on the train to see Hair and saw nudity on stage; so risque! We listened to the Beatles, The Seekers, Cat Stevens and Peter Paul and Mary amongst others, on vinyl of course.

Margaret had begun teaching at Moe in 1973 and Jono and I, after a year overseas, both taught at Drouin High School, quite nearby. By the end of the decade, I had given up teaching and was at home at Gowar Avenue with a three year old Anna. Margaret was teaching at Croydon and was living in Gully Crescent with Ken.

Conclusion.

Marge and Alice finished their oral family history with their weddings and the end of the Second World War. It was neat: 1850-1950. It left off when they were both about thirty, settled into the business of raising children.

We are finishing our own overview at the corresponding stage. For us, this is 1980.

In the very last minute of the recording Alice, by herself for this part of the process, reflects on the speed of technological change that she and Marge had witnessed in their lifetime.

“But there’s a sort of corresponding suddenness in those new technologies and we tremble, as we think you do too, at what the outcome of all this is going to be for your children.

So looking back over that hundred years, we see this period of rapid, strong and significant development: a development that began gently enough, but now, in 1990, is rushed and killing and devastating.

And we look forward into the future for you and for our grandchildren as a time where perhaps you will learn what de-development is all about, and maybe the graph is going to go gently and firmly and calmly for you, into a period that is not as frantic as the one we’ve lived in.”

Strikingly and shockingly, the suddenness and the devastation she speaks of in 1990 has not diminished, but increased. And now, in 2018, as we watch our own grandchildren navigating their way into the world, we too tremble at what the outcome of “all this” will be.

I can hear sleigh bells

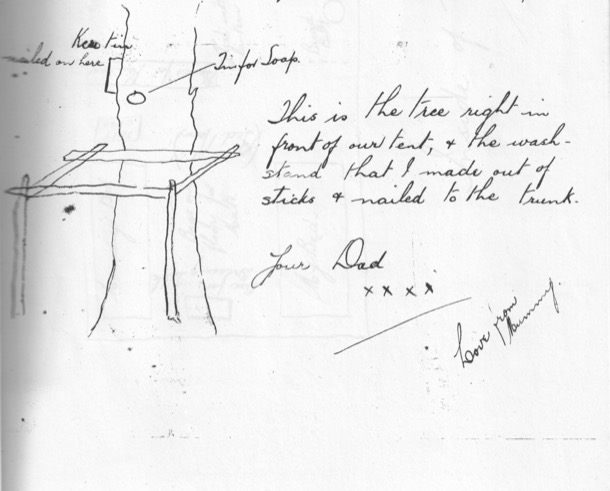

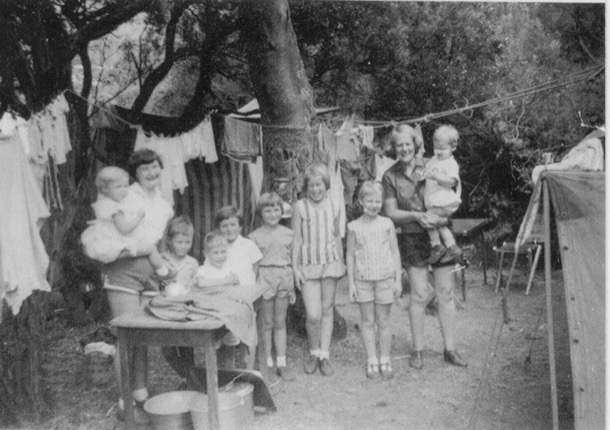

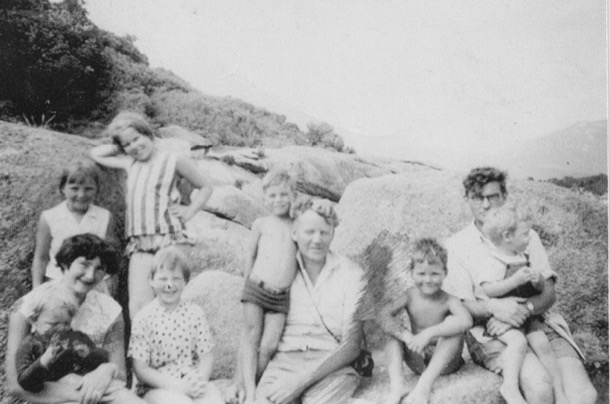

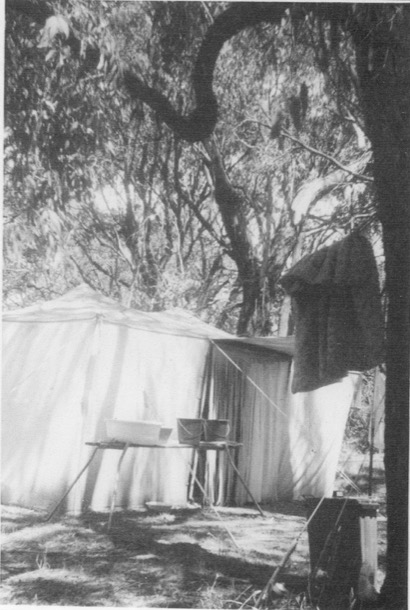

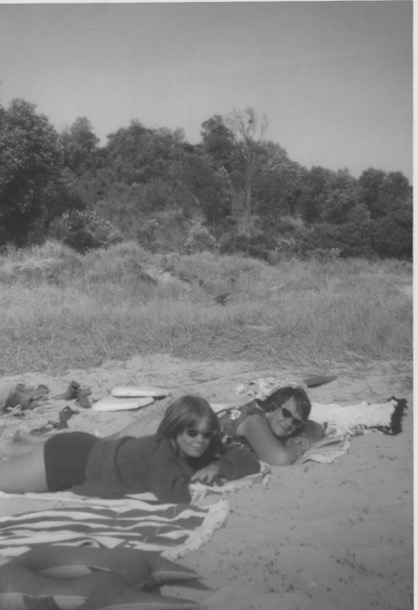

Christmas also marked the end of the school year and the beginning of holiday preparations. When we were very young, this involved a wonderful week staying with Pauline, Auntie Marge and Uncle George and later, the huge preparations for camping at Shoreham.

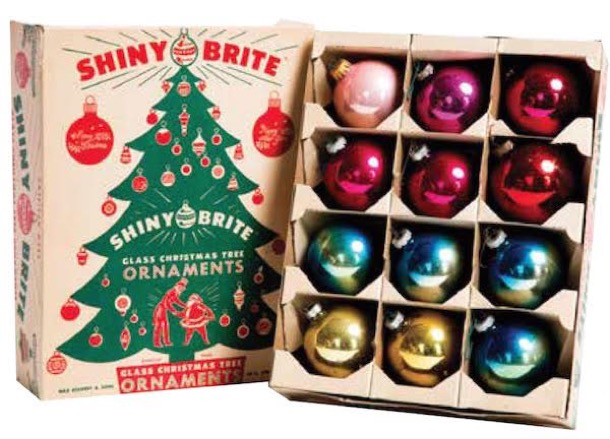

In our minds, Christmas preparations are linked with images of Mum sewing at the kitchen table; cotton ends; bits of material with paper patterns securely pinned to them; standing still to have hems pinned up; and the last minute wrapping of presents amongst the sewing detritus. Dad was packing the trailer and driving to Shoreham to set up the tent. Our parents must have been very busy, but we remember it as a very happy time. Margaret and I remember decorating the tree that was of course a pine tree.

Christmas baubles were made of glass: fragile and expensive.

Choosing the tree was quite a process, as was the decorating, as trees were irregular shapes, not manicured as they are today.

With Mum so busy sewing, it was also easy to slip unnoticed into the dark, tall built-in cupboard in their bedroom, where every year, on the second top shelf, mysterious exciting items in brown paper bags were stored. We remember doing quite a bit of poking and prodding, but never unwrapping and having a real good look. This would have to wait until Christmas morning.

Margaret and I also saved our pocket money for Christmas and bought presents for Aunts, Uncles, Great Aunts and Grandparents. We had wonderful fun in the Coles Emporium in Box Hill choosing the most wonderful pressies.

We choose strong smelling bath salts for Auntie Bert, delightful ornaments for Grandma Bourke, talcum powder for Auntie Tish and often disappointingly, hankies for the men, as they were very hard. The shops, even the department stores, were very, very different. A few Christmas decorations were evident, but shops generally were less cluttered, as there was little if any self service.

Once purchased and examined we wrapped the presents, made and wrote cards, and either posted or delivered them personally on Christmas Day. Sometimes we also made presents. One year it was calendars. We made them with a prepared calendar printed format and found interesting pictures to paste in for each month. Great fun!

Another delightful memory is of the Salvation Army brass bands who marched the suburban streets before Christmas, stopping every now and again to play three or four carols on a corner. If we were lucky they would stop nearby and we could peer out the window and see them in their uniforms playing the shiny brass instruments. It was always disappointing to hear the tread of feet in unison, as they marched away to the next spot.

One such very hot night , Christmas Eve actually, the Salvation Army Band had moved on and apparentIy I convinced Margaret that we could hear sleigh bells. Margaret is not sure of it but I am!

I must have been about seven or eight when my suspicions about the identity of Father Christmas were confirmed, although I did still try to deny it and believe for a few years after that. We were staying in a little fibro holiday house in Rosebud with another family. The children were squashed in together in one room, on beds and mattresses on the floor. Late on Christmas Eve, I saw two figures, our parents, laden with crinkly, crunchy pillowcases, stumbling around the crowded room putting the ‘sacks’ on the respective beds. I remember telling Mum that I had seen them, and being cautioned to keep the knowledge to myself. I did!

Christmas Eve for us didn’t involve special preparations or rituals, other than the placing of a pillow slip on the end of each bed. We called these “sacks”. Sue remembers “hearing” Santa’s sleigh bells one year, and sometimes the Salvos street-corner concert would be on this special night, but generally the excitement began on waking.

As soon as I remembered the specialness of this particular morning, I would reach out my toes and touch the lumpy sack that now took up a good ideal of the bottom of the bed. The crinkle of wrapping paper and the solidity of its contents were thrilling. Sue and I shared a room, and the first one awake would wake the other. I guess we woke the two boys too, or perhaps they woke us up.

The ritual was then for each of us to carry our sacks up the hall to our parents’ room and have a mass unwrapping there, on their bed.

When Sue and I talked at length about our reminiscences of our childhood Christmases, one of us raised the question of what presents we remember. The answer is: hardly any. And yet we had very few toys, and only two occasions, Christmas and birthdays, when we got any.

“Stuff” was very expensive and in short supply when we were little. And clearly it was not terribly important in our lives. In our sacks there were one or two intriguing and fairly roughly wrapped parcels. There might be a toy, maybe some “special” clothes, a bag of mixed lollies, chocolate coins, eaten then and there, and little else. One year we were given hard cover bibles, (not very exciting). Later in the day, we presume there were presents from other family members, but we do not remember the actual items, just the excitement of unwrapping and the specialness of the occasion.

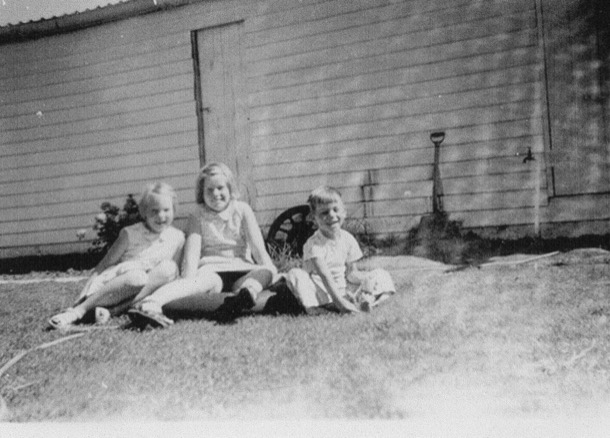

A rare Christmas picture, about 1962. Margaret, Ian and Chris.

One Christmas morning I do clearly remember, was when I woke to find a trail of wool from my sack leading to the large room at the back of the house we called the rumpus room. When I reached the end of it there was a card telling me that my new piano would be placed here. There was a corresponding card on my sack saying that the next year I would start having piano lessons. I had been asking whether I could learn the piano for some time, and, looking back from here, it seems as if I knew that this was going to be very significant in my life.

Other presents we remember which could just as easily have been birthday presents are:

The joint present to all of us of a swing. We got out there early on Christmas morning to use it, and made ourselves sick.

A pogo stick, another joint present.

Roller skates, which attached to our shoes. (Only the boys had bicycles, though we had tricycles when we were really little)

Dolls: mine was black and Sue’s caucasian.

Beach toys, such as bucket and spade, and, later, rubber blow up surf matts.

After we had strewn our parents’ bedroom with paper and eaten far too many lollies and chocolates, we had our usual breakfast of cereal, sugar and milk, put on our “best” dresses, socks and either our school shoes, or sandals (we only owned one pair of each) and headed off to church.

Sue remembers the Christmas church service as “a little less boring than usual”. For me, church was all about the music. The Christmas church service was overflowing with once-a-year-Christians and there was an air of excitement among all age groups.

After church there was a small, not very special lunch at home, and our mother doing last minute wrapping of presents for the afternoon. Then, I guess still wearing our best, (although some of us were quite prone to getting extremely dirty extremely quickly), we headed off for the afternoon at Grandma Bourke’s place.

It is about this part of Christmas Day that I have the clearest recollections.

We have written in another post (“Cut out of the Will” 15/6/2016) about our parents’ ”mixed marriage” and the disapproval with which their union was viewed.

Our mother called her mother in law “Mrs Bourke”, which was also her own name of course. We were aware of the tensions between them, and acutely aware of the warmth and familiarity between “Grandma Bourke” and her other grandchildren, who lived in the country and stayed with her every Christmas. They called her “Gannar”.

Presents were exchanged, as we sat in a circle. Interestingly, while we can remember giving presents to the grown ups, Grandma, Auntie Tish and Uncle Matt, we don’t remember any specifics of the presents we were given.

Mostly, for us, these visits were about the food. Afternoon tea, in the front room, stuffed full of dark furniture, was a grand affair. There was a huge silver teapot with its cosy, on a double decker tea trolley with cups and saucers. There was cake, slices and delicious savouries in huge quantities.

The grownups made conversation, about things that were not of our world: the races, farming the cattle property that Uncle Matt owned in the Western District, television, (Grandma Bourke was a huge fan of Graham Kennedy) and people we didn’t know.

Afterwards we children went outside under the weeping elm tree in the front yard, to play. It is only there I have any memory of interacting with our cousins, and not much there either. They were younger than us, and lived in a very different world. Occasionally our other cousins, Uncle Jack’s children, even less familiar, would come to visit on Christmas Day.

Some years, this was the end of Christmas for us. We went home for a light dinner and woke up to the rest of the holidays, which, in later years, meant six weeks camping at Shoreham.

Sometimes, though, we went on from Grandma Bourke’s in Hawthorn, to Beaumaris and our mother’s sister’s place. After the stiff, tense formality of Grandma Bourke’s, Auntie Marge’s warm welcome and the relaxation of playing with our familiar cousin Pauline, was a huge relief. We would have a wonderful meal and exchange presents lounging around the floor in the spacious living room. There was even a glass of wine (Penfolds Moselle in a flagon) with dinner for some of the adults. Alcoholic drinks did not feature in our parents’ lives.

We did not see our maternal grandparents on Christmas Day. We have no memory of them sharing anything Christmassy with us, even when they were living with us.

Most families have developed Christmas traditions. We remember Christmas as being confined to the day itself and the night before, and we suspect this might have been a common thing in those days. Our family did not entertain. There were never any parties, even family parties. When we look back on this time, and compare it to what kids these days experience as Christmas, it was pretty sparse. Sue and I, reflecting on our childhood Christmases, are aware of, and a bit surprised at, how warmly we remember them.

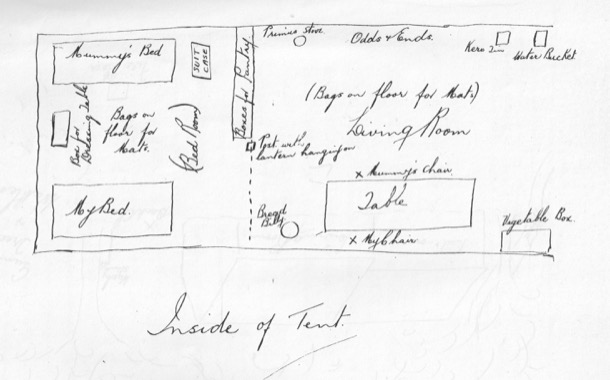

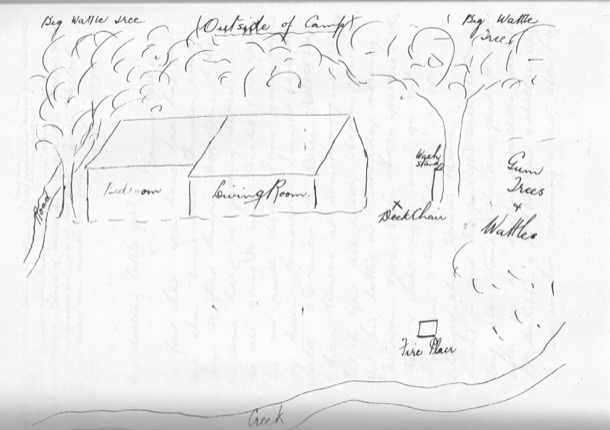

The Farm

About 1950, our mother’s aunt, Beat, and her husband Bill sold up their grocery store and their Balwyn house, took their youngest son out of school, and bought a dairy farm in the Dandenong Ranges at Nangana, near Cockatoo.

It was called “Sefton Park”, but it became “The Farm” to us, as we were growing up, and it was one of the very, very few places we visited socially.

By the time we were regularly visiting The Farm, the eldest son, Doug had married and moved out. He became a bus driver and spent his whole life living at Avonsleigh, near Emerald.

The next son, Rob, had married young, built another house on the property and had a child, Julie. Rob’s wife, Pat, died of breast cancer when Julie was still a baby, and Rob moved back to his family home. About that time our mother’s unmarried aunt, Bert, moved to The Farm, presumably to help her sister with this motherless baby.

So this rural property supported Beat and Bill, Rob and his daughter Julie, youngest son John, and Beat’s sister Bert.

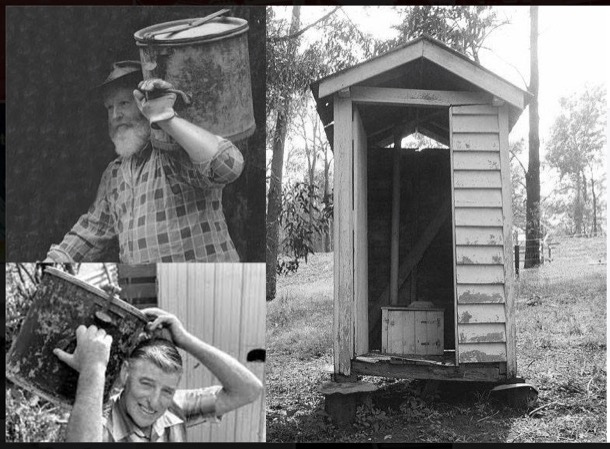

Auntie Beat and Uncle Bill:

Down at the creek. From left to right (we think): Auntie Beat, Uncle Bill, Rob, Pat, Doug and a neighbour or visitor:

When I picture the farm and its people, in the 1950s, I see Auntie Beat and the men in layers of worn out hand knitted woollens: shapeless jumpers and cardigans, beanies, fingerless gloves, scarves. Auntie Beat wears heavy woollen skirts, thick stockings and socks. By the back door are a row of huge gumboots. Everywhere out side the house is mud, and away from the immediate house and garden, they all wear gumboots. In the dairy they wear heavy canvas coats or aprons. In the house, images of checked aprons, floury hands come to mind.

The journey to the farm with four children in the back seat, or perhaps Chris on Mum’s knee, always seemed a happy and interesting trip. It was about forty-seven kilometres from Box Hill, mostly through farmland, orchards and bush, and probably took us about an hour and a half.

The first highlight was Bennett’s Cottage in Burwood Road, on top of the hill just past Station Street. The crumbling walls of the wattle and daub hut, of one of the early white settlers, still stood in a paddock. We were told all about wattle and daub and the early settlers, and it remained in my mind into adulthood, as something to be marvelled at.

The next landmark was Tally Ho Farm and Boys' Home, on the corner of Springvale Road and Burwood Road. This marked the beginning of the country as the road shrunk to a narrow strip of bitumen that ran in a straight line between orchards and paddocks to the next hill at Vermont.

It then wound its way to Upper Ferntree Gully, then a small town at the base of the Dandenongs. Our route through the Dandenongs always took us through Belgrave, Selby and Menzies Creek to Emerald. From here there were several options but the routes we took are hazy. The only clear memory for both of us is of a very lovely narrow, undulating, dirt road through the bush.

Woori Yallock Road:

Sefton Park, as The Farm was named, spanned the road. The creek flats, which were on our left as we approached the farm, ran down to the Woori Yallock Creek that flowed alongside heavily timbered hills. These were the jewel in the crown and were known as ‘the flats’. At this point we could get a glimpse of the dairy and the roof of the house. White painted fences bordered the drive and framed the gateway of the cypress-lined drive to the house. The house, dairy and sheds all sat on a small hill probably an old levee bank of the creek, so the drive sloped gently up to the house.

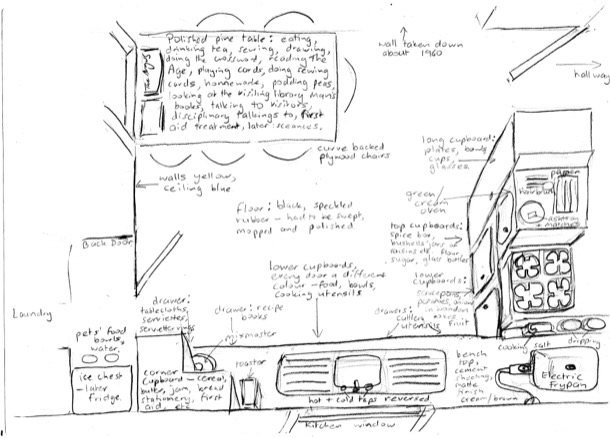

As we piled out of the car, the farm dogs under the cherry plum strained at their chains and yapped, and Auntie Bert and Beat could be glimpsed walking up the garden path wiping their hands on their aprons. Greetings, hugs and queries about the journey over, we adjourned to the kitchen for afternoon tea. The house was entered from the back door that opened into a wide spacious hallway from which opened the bathroom and the hallway leading to Auntie Bert’s room and the boys bedrooms. The kitchen was occupied by a very large rectangular kitchen table where most of the food preparation and meals etc took place. At the far end under a window was the kitchen sink and in the chimney opposite the door was the wood stove.

The toilet was in an unpainted wooden building down a winding path from the house. The heavy wooden door was held shut with a small rectangular block of wood which turned through ninety degrees. It was dark, smelly and spidery inside.

On a wide, flat platform facing the door was a handmade heavy circular lid, topped with a wooden handle. The bench was too high for little girls to be able to properly lift the lid, so it was wriggled sideways to reveal a deep dark chasm.

Mounting the platform and inching back so that one was seated over the fetid depths was an act of courage. I remember my legs stuck out straight in front.

Dismounting required wiggling forward and revealing once again the dark depths.

We had toilet paper in our much less terrifying outdoor dunny at home. Here, there were squares of scratchy newspaper on a string.

It was important to remember to replace the heavy circular lid, and then to wash our hands in the bathroom, just inside the farmhouse door, with a thick slab of yellow soap.

In winter of course the house was toasty warm. We all sat down to afternoon tea and ate scones with lashings of farm cream and all washed down with copious cups of tea and farm milk of course. After news was exchanged the ritual of the visit dairy to watch the milking and the pilgrimage to the pigs took place.

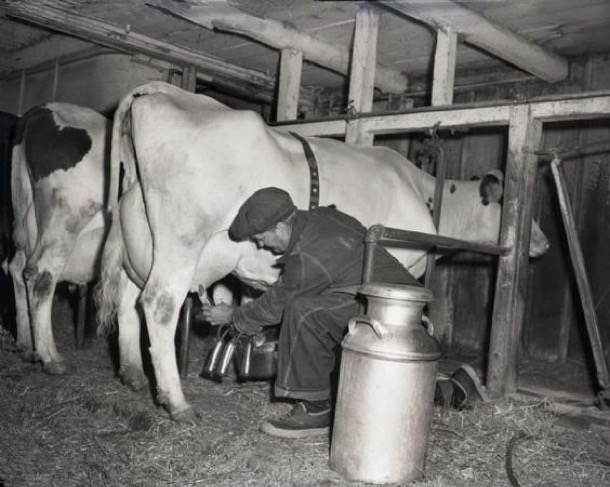

The main business of the farm was dairying. They had a herd of dairy cows: jerseys with huge liquid eyes. There were farm dogs, but the cows made their own way up to the dairy, in the late afternoon, following muddy, well trodden paths through the paddocks.

In turn they filed into the dairy, and into one of the six milking stalls, and the noisy diesel powered machine cranked up. The teats were washed with an old towel in a bucket of soapy water, a loose chain was put under the tail around the rump, and a set of shiny metal tubes was attached to each udder, with audible sucking sounds.

Each cow chewed contentedly on food in a trough at the back of the stall, as her udder, hidden by the tubes, pulsing rhythmically. Eventually she would finish, be set free and make her way out the back of the shed and another would plod in to take her place. I remember being very impressed by the way the cows seemed to know what to do.

The only glimpse of the milk itself was in a high up glass ball into which the milk pulsed as it was pumped into the room behind the dairy.

After the last cow had made her way back out to trek slowly down the hill, the clunking machine would be turned off and the clean up would begin.

Dairy farming involves the sad business of poddy calves, separated from their mothers and sold. We remember calves being fed from a bucket, but not the significance of this.

The dairy business sold cream, separated from the milk in a high tank. This used centrifugal force to collect the lighter cream and send it through a separate channel. We remember the whole milk being pumped into the tank along a wide, shallow chute.

The remaining skim milk was used on the farm to feed the pigs, Auntie Beat’s pride and joy.

The milk was mixed with some sort of grain to produce a mash, which was poured into troughs for the pigs.

Our visits always involved trekking down to the smelly pig sheds, where huge sows sloshed around or lay on their sides, in spacious, but muddy pens, surrounded by little pink and brown piglets. They also had access to the surrounding paddock: it was a far cry from modern factory pig farming, a cruel and hateful process. I can’t find in my memory any emotion connected to the actual pigs. Sue remembers cuddling the hand-reared orphan piglets in the kitchen by the slow combustion stove and the boar, who lived permanently in the muddy paddock.

We’re not sure exactly how many pigs there were, but there were about four pens, where the sows and piglets were. Possibly they were only kept in those pens when they had their piglets, and roamed in the paddock the rest of the time.

I remember Auntie Beat lifting the massive lid on some huge ground level tanks to proudly reveal a seething mass of fat maggots, her clever way of dealing with the pig excrement.

I remember our mother’s wry amusement at Auntie Beat’s enthusiasm for the pigs. Apparently she had been an elegant and sophisticated lady in her earlier life. But this version of Auntie Beat, sloshing around the pigsty in her gumboots and several layers of shapeless cardigans was all we knew.

Mostly I remember the smell!

Quite often while the grown ups were chatting we were allowed to play in the hay shed with Julie. It was such fun! The hay shed was a traditional barn shape and covered in red painted galvanised iron, peeling. Most of the painted surfaces at the farm appeared to have peeling paint. It was open on one side, so it was light and airy and a child's paradise.

Rectangular bales of hay were stacked to the roof along the back and then in descending tiers. Chooks and cats played, scratched and slept in there too. We climbed all over the bales up to the roof, built cubbies and played.

There were a few variations to this routine that I can remember. Once we went shooting on the flats with Dad and I was allowed to have a shot at a rabbit and on a few occasions we went blackberrying. We also went for a big walk up the hill over the flats. An exciting ride down to the flats in the tractor trailer and over rickety home made wooden bridge, was followed by what seemed like a big walk up the wooded hill to the top. The best adventure though, was the day we visited during hay cutting season. I can still picture it. It was a lovely clear summer day. We watched the dry, cut grass baled up into the neat rectangular bales we were familiar with in the hay shed.

Towards evening, after the milking, it was time to leave. Laden with fresh cream, milk and flowers, we made our way up the garden path to the car. After many warm hugs, we began the journey home. Often it was dark by the time we passed Emerald and it was at this point in the journey that we sometimes sang. The Ash Grove features in my (Sue’s) memory, as it was hard for me to get to the high notes. The rounds we sang were also fun and a very good activity for tired children squashed into the back seat.

‘The Farm’ visits remain in our memories as fun, and an adventure in our simple lives. It was not only because we played in hay shed and joined in the farm activities, but because we were very fond of Auntie Beat, and particularly Auntie Bert.

‘The Farm’ is still a working property today. Rob remarried, another Pat while Bert and Beat were still alive and living in the old farm house.

Rob and Pat built a new house in the front paddock, had a family, and took over the working of the farm. Tragically, Rob was killed in a tractor accident when the children were still young. Pat stayed on, running the farm, looking after the children and working part time as a nurse.

We have visited infrequently since Bert’s and Beat’s deaths, briefly making contact again when Jono and Sue kept bees in the top paddock.

This photo was taken in 1983. In the background is the old farm house. Back row from left to right: pregnant Margaret, John, Jono and Alice, our mother.

The farm is in good hands. Pat stopped the use of fertilisers in the paddocks and the dairy herd became a totally organic operation. Today one of Pat and Rob’s sons runs a very successful organic vegetable growing business, supplying top Melbourne restaurants with fresh produce. Beat and Bill would be pleased that today one of their great grandsons still works the farm.

Here is an aerial view of the farm today. The original farm buildings are in the bottom of the picture. Pat’s house is on the other side of the drive, closer to the road. Today it is surrounded with greenhouses.

Meat and Three Vegs

Like many families, we were fairly poor as we were growing up. There were four children, only our father worked and "stuff" was very expensive. Food, however was relatively cheap, locally produced, fresh and plentiful by the time we Baby Boomers were on the scene. Our mother had been taught to cook by her mother, and the repertoire was pretty simple and limited in scope. Our mother was an ok cook. She knew not to boil the proverbial out of the cabbage, she used the limited available range of flavourings sensitively and she was open to the few new ideas that came her way.

As the fifties became the sixties, there was a fridge rather than an ice chest, the Womans' Weekly began to suggest new adventurous culinary ideas and there was a greater range of food in the shops.

In early 1964, when I was twelve and Sue was fifteen, our mother got sick. She had a condition called Thrombocytopenia, or low platelet count. Platelets allow blood to clot, so a person with not enough of them is in danger of haemorrhage. Eventually she had her spleen out and recovered. But for that year, she was tired all the time and generally felt terrible. Our youngest brother was only seven.

I remember a conversation early that year with a very serious Mum and Dad, just with me. The proposal they were putting to me was that I take on all the family cooking, to remove that burden from Mum.

I had been a kitchen assistant to her for a number of years. My memory of those years was that Sue cooked occasionally and always special, flamboyant things like interesting cakes, and that it was me who made the gravy and the custard, peeled the apples or rubbed the butter into the flour, often with my mother shutting the drawers in front of me, or wiping up my spills, complaining about how sloppy I was. (I still am!)

So, at age twelve, I became the family cook.

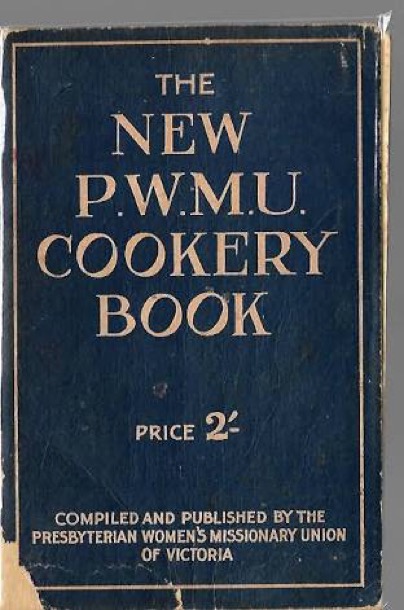

We hardly ever used actual recipes. Most meals were just cooked the way generations before had cooked. Even so, recipe swapping as a social activity was as prevalent then as it still is. Mum’s recipe book often had the name of the source: Joan’s biscuits, etc. Sometimes they were written on the back of an envelope or a scrap of paper and stuck in. There were also torn out recipes from magazines and newspapers. And there was also the PWMU cookbook.

We were a family of six. We had an evening meal of meat and vegetables and dessert.

Three meals a day and morning tea were provided. Nothing was drunk with any of our meals, not even water. There would have been a cup of tea afterwards, but not at the table. After school and other hungry times we had unlimited access to bread and butter, and fruit. (almost exclusively apples and oranges). I remember mum saying, “fill up on bread”.

Evening meals

We always had meat, served mostly with potato, but sometimes white rice. Also on the plate were two or three other seasonal veggies. These included cauliflower with white sauce; lightly cooked shredded cabbage; diagonally cut string beans; fresh peas; boiled silver beet; carrots cut in rings; mashed pumpkin; brussel sprouts, cooked whole; carrot and parsnip together mashed with butter; marrow cut in rings, boiled and served with lots of butter, salt and pepper; leeks in white sauce; broad beans, included the pods. In the summer we often had a salad made from iceberg lettuce and tomato and some of: green capsicum, celery, peeled cucumber, and, later on, the very glamorous addition of chopped apple and orange. The salad was liberally dressed with home made salad dressing. This was made by beating up a tin of sweetened condensed milk with mustard, malt vinegar and salt. We also had pickled beetroot.

Here is a fairly comprehensive list of the “meat” part of the meal:

Roast leg of lamb, roasted with potato, pumpkin, parsnip and onion. This was served with a green vegetable cooked separately; gravy, made in the roasting pan from thickened meat juices; and freshly made mint sauce. Dad was always the one to carve, but not ceremoniously at the dinner table, rather, at the kitchen bench and the portions were doled out from there.

Roast beef, “corner cut”, roasted with the same vegetables.

The same roast meats, served as cold meat or fritters, with chutney.

Grilled loin chops, two each.

Corned beef, boiled. Warm with cabbage and potato, then as cold meat on subsequent nights.

Four quarter lamb chops, stewed with onion, carrot and peas. Served with mashed potato.

“Rice meat” - chopped veal, stewed with onion, stirred into plain white rice, peas, parsley and lots of pepper.

Smoked cod, boiled.

Steak, corner cut sliced about a centimetre thick, fried in the frypan, until it was grey inside and hard on the outside, served with worcestershire sauce.

Lamb shanks stewed with carrots and onions.

Gravy beef (stewing beef) stew. Served with mashed potato and other vegetables.

“Mr Wilkinson dinner” - boiled white rice, topped with minced steak cooked with mushroom soup, and shredded, lightly cooked cabbage. (This meal was introduced to us by the eponymous Mr Wilkinson while the two families were camping at Shoreham. On a two burner stove, it fed four adults and ten children.) (I still use this as a meal, although these days, I use a tin of lentils and fresh mushrooms.)

Spaghetti served with meat sauce (fried onion, tinned tomato and minced steak, thickened)

Ham steak and pineapple. (both fried in dripping)

Sausage meat rissoles, fried in dripping and served with mashed potato and “tomato sauce gravy”. The gravy was made by browning a big spoon of flour in the frying pan, then adding tomato sauce and water.

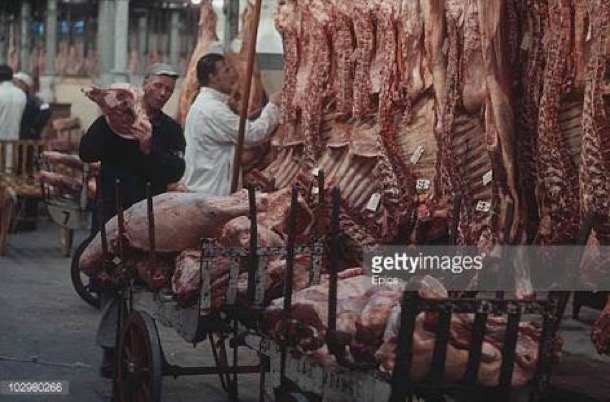

Pan fried fish. This was usually barracuda, bought at Vic market, served with chips bought from the Wattle Park fish and chip shop.

“Chow Mein”. This was made in the frypan: minced steak, dried chicken noodle soup, pineapple pieces, green pepper, shredded cabbage. Served with boiled white rice.

Meatballs made of minced steak flavoured with dried soup mix and cooked in a sauce made of tomato soup and chopped green pepper and tinned pineapple. Served with boiled white rice.

Lambs fry, (liver) fried with tomato sauce gravy, served with mashed potato

Camp pie (like spam) and tinned real ham - almost exclusively when we were camping.

Mum’s father, over the years when I was the family cook, lived alone in the flat the the back of our house. He also had to be catered for, and he had very specific tastes. He shared the dessert I had made, but for his main course, he insisted on his own menu. He would have on alternate nights, two grilled chops or stewed lamb shanks. And he didn’t even have the same vegetables as the rest of the family. He only had potato, carrots and beans. This meal was delivered to him before the rest of the family ate. I remember Mum wryly saying that he thought he was very easy to feed, because he had such simple tastes. Occasionally there was a complaint, delivered indirectly to me via Mum. Too much salt on the grilled chops, is one I remember.

Desserts

Dessert was a staple. We had it every single night. It nearly always had some fruit component and was served with home made ice cream (evaporated milk, sugar, vanilla, eggs), custard (made with custard powder and egg), sweet white sauce or “top of milk”, from the top of the unhomogenised milk, a bit like thin cream.

Apple sponge

Apple crumble

Baked whole apples, sometimes covered with pastry.

Jam roll

Bread and butter pudding

Steamed pudding - plain with jam in the bottom, served with custard, or butterscotch made with golden syrup, served with sweetened white sauce.

Tinned fruit

White rice with sugar sprinkled over it served with milk

Rice pudding

Jelly with fruit set into it

Golden syrup dumplings

Apple snow

Sago, cooked in a white sauce (looked like frogs’ eggs)

Junket, like a baked custard, with nutmeg sprinkled on the top.

Baked fruit, or sometimes tinned fruit, with a crunchy topping made with Weeties, sugar and dotted with butter

Banana custard

Television pudding. this was a self saucing chocolate pudding. It was Dad’s mother’s recipe, always called this, even though long before had a television.

Apple Sponge

Breakfast

Weeties or Cornflakes with sugar and milk

Winter: porridge, with creamed oats (Creamota), sprinkled with brown sugar or golden syrup and milk.

Toast only on weekends or holidays

School lunches