"Cut out of the Will"

Growing up we had heard many times how our father had been ‘cut out of the will’ by his father because he had married a Protestant and renounced the Catholic faith.

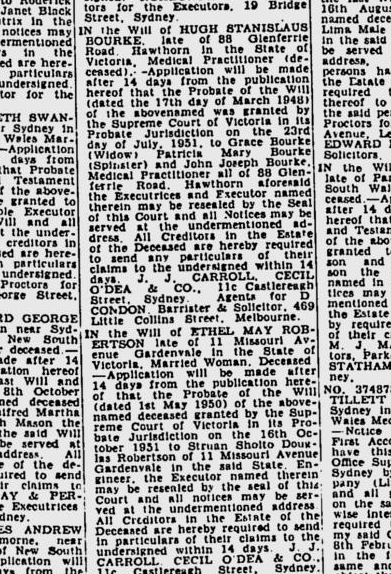

As we were researching the early life of our Catholic grandmother Grace, we stumbled across the application for probate for the will of Doctor Hugh Stanislaus Bourke, our grandfather. His widow Grace, his son Jack, his daughter Patricia are mentioned but no mention of James Vincent Bourke his second son, our father.

Here, published in the Argus Newspaper, was the brutal reality of what this divide really meant in our parent’s lives. It was no small sum: 36,353 pounds. In todays world this would be equivalent to leaving an estate valued at six and a half million dollars.

More shocking is the date, on which the will was written March 17, 1948: not when they married, but three years later, when Alice was only just pregnant with their first child who was not going to be raised as a Catholic. Was this the catalyst?

Australia and the Irish Catholic/English Protestant divide.

In the very earliest days of the NSW penal colony, many of the convicts and early settlers were Irish catholics, and most of the British Military, who ran the prison colony were Anglican protestants.

The first few decades of the colony coincided with unrest and rebellion in Ireland, which was still under English rule. The authorities were nervous of the very large numbers of Irish convicts and settlers, who spoke their own language and had a different religion.

Most of Ireland became a republic and a separate country in 1922. Although there was still unrest in Northern Ireland, which remains part of England to this day, most of the official heat went out of the Irish English divide, though it remained in people’s consciousness.

Australia had an influx of European migrants in the nineteen-forties and fifties, and gradually the clear division of Australian into Catholics and Protestants became blurred, though there was still institutionalised prejudice against Catholics, right up until the 1980s.

The other: the mysterious Catholic world seen through our eyes.

Dark, heavy wooden framed paintings of the Virgin Mary and the Crucified Christ were the mysterious evidence of the Catholicism of our grandmother. We only visited Grandma Bourke’s house three or four times a year for very formal, if delicious, afternoon tea. Our relationship with her too was very formal, a peck on the cheek hello and goodbye and no spontaneous hugs and signs of affection, as we saw our cousins receive.

We knew nothing of this strange Catholic world as we were Protestant and our parents were both heavily involved at St James Presbyterian Church, Wattle Park, where there were a few bare crosses, but no other iconography.

The dark religious ‘icons’ we saw in Grandma’s house were also to be found in Uncle Jack’s house in Glenferrie Road. Most mysterious was the large porcelain statue of Mary. Mother of God, clad in a pale blue robe and further upstairs another large porcelain statue of the Crucified and Risen Christ complete with bleeding nail holes. Gruesome stuff!

When we were growing up, even though we had Catholic relatives, we would never have gone into the Catholic Church. On several occasions we saw, at the local Catholic Church, little girls dressed up as Brides of Christ, lined up and waiting to process into the church for their First Communion.

Nuns in full habit were also very much part of our early memories. I remember back shiny lace up shoes visible under the long heavy black robes, the white starched wimple and veil and, above all, the clanking sound of the Rosary Beads and keys on a chain around their waists.

Even though, by the nineteen forties, there were Catholics in all walks of life, ordinary people still defined themselves and each other by whether they were Catholic or Protestant.

They went to separate schools, even at primary school level. If you went to a Protestant private school, you bought your uniform at Myers. Foys, another department store, catered for the Catholic ones.

Catholics were forbidden to set foot in a Protestant church. One story from this time is of the brothers of a Catholic woman marrying a Protestant forced to stand outside and watch the ceremony through the window. When Protestants and Catholics married it was called a “mixed marriage”

There was lots of name calling… “Micks”, “papists”, “proddy dogs”. Our father, attending the Catholic School in his home town of Koroit during the nineteen thirties, told us the story of him running home, chased by kids from the state school, turning and calling “proddy dogs, jump like frogs” or perhaps it was the others calling him a “Catholic dog” … probably both.

So when our father, Jim, told his Irish Catholic parents about his new girlfriend, there were probably alarm bells right from the beginning. Jim and Alice met at work, the Maribyrnong Munitions Factory.

They married in 1945, a couple of months before the end of the war. She did not dress as a bride, because it was still war time, and they had a quiet ceremony in the Congregational Church in Surrey Hills, near Alice’s home and a reception at Wattle Park Chalet.

The couple lived with her parents, Alfred and Alfreda, until they built and moved into their own house in the early nineteen fifties. Alice’s parents seem to have been very tolerant. Their eldest daughter had married a Hungarian Jew a few months earlier and now their other daughter, a Catholic. Theirs was a working class family, educated and valuing education, but without much money or position in society.

Jim’s parents were from a different class as well as a different religion. Grace, as we have discovered had been a society girl and Hugh, a well respected country doctor. They did not come to the wedding. We can only imagine the conversations, the arguments, the pleading. To them, Jim’s parents, their precious son was denying himself an afterlife in Heaven, and bringing shame on the family. Any children born to this marriage would be viewed as illegitimate. In the eyes of the Catholic Church our parents were not married.

One “family story” tells of Jim’s sister, Tish, writing a letter pleading for them to “marry properly”. As children we knew that our father had “left the Catholic Church” in order to marry our mother and that he had been “cut out of the will”. It is part of our family mythology. We were aware of our mother’s bitterness at our family’s financial struggles. We witnessed the stiff courtesy with which she greeted her mother-in-law, who she always addressed as Mrs Bourke.

Now, looking at the stark reality of this newspaper article, we feel a little of her outrage. We understand better the enormity of that decision, the extraordinary timing of Hugh’s change of will, the sense of being the ‘black sheep” family that hung over us when we visited out Grandmother.

The Poor Little Thing

Marge and Alice, with great drama, tell the story of our great, great grandmother whose name they do not know, and her subsequent marriage to Grandfather Dow, with whom she had eighteen children.

They had little factual information and their story is obviously based on stories told to them by their father. “That’s how the tale goes and the imagination boggles,” says Alice at one stage and indeed it did!

THE FAMILY TALE would have us believe that the our great, great grandmother, name unknown, met her prospective husband, first name unknown, at the Victoria Market. She was apparently a child of fifteen dragged off by a middle aged man to a poor farm miles out in the country of early colonial Victoria. The long and arduous journey into the night finished at Wandong where the poor little thing, ‘rolled up her sleeves and started milking cows straight away.’ She bore eighteen children and did much of the work, as her husband, a German immigrant from Bavaria, who was rumoured to have noble blood, sat behind the milking shed reading poetry. The poor little thing lived to 83 and grew very broad in the beam. Her husband as the tale goes died at 102 sitting up in bed singing a hymn.

The mind does indeed boggle. Was she a poor little thing? How much is ‘tale’?

You be the judge.

We also have a story extrapolated from FACTS provided by the Victorian Records Office, Ancestry Dot Com, Google, newspapers, shipping records and documents from England.

The ‘poor little thing’ was Martha Rye born in 1850 in Geelong in the Colony of New South Wales. The year after her birth in 1851 the Colony of Victoria was founded and separation from New South Wales was formalised.

Martha Rye was the first child born in Australia to Adam (1822 - 1924) and Elizabeth (1824 - 1901) Rye, recently arrived immigrants to the young colony.

Adam and Elizabeth emigrated to Australia from South Lopham in Norfolk, England in 1848. They had with them one child, Marianne who was a year old. Adam was twenty-six and Elizabeth twenty-four.

Here is the South Lopham church in which they were married:

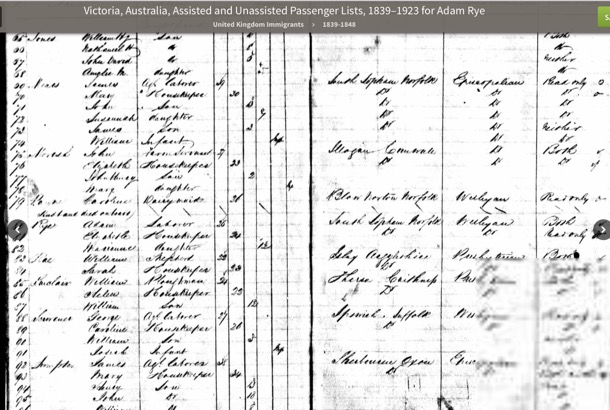

We know from the shipping records that they sailed on the sailing ship The Berkshire, arriving in Geelong on October the third, 1848. Their occupations were listed as labourer and housekeeper. He could read and write, she could read but not write.

We know that he had indeed worked as a labourer on his father’s farm, but he had also had a stint as a footman in the household of Lord Randall, which is where he tasted a bit of Queen Victoria’s wedding cake, shared with the staff by Lord Randall, who had been a wedding guest.

When he and Elizabeth left for Australia, they sat down to a farewell dinner with thirty-two of Adam’s brother and sisters (from three different mothers).

Adam lived 102 years, and when he was in his nineties, his colourful life story was written up by an enthusiastic journalist for a local paper. Note his editorialising in the following extract about “treacherous blacks”.

The family settled near Geelong, where they rented a piece of land to farm.

“While here Rye went off one day to the store for provisions, and after getting his supplies started for home, but darkness overtook him and he lost the track. He wandered about for some hours, and at last came upon a party of about 50 blacks. He thought it was no use trying to run away so he had to stand his ground. The blacks took his supply of bread, cheese, tobacco and a bottle of rum away from him and divided them amongst themselves, never leaving him a bite. Towards morning he made them understand where he lived and they directed him to his home, but having found out where he lived they paid him a couple of visits at night time and carried off his potatoes - not any that came to hand but the biggest and best and potatoes were worth £30 a ton in those days. The blacks at this time were very treacherous. They would watch the mothers going away for water and would steal into the huts and carry away anything they fancied even occasionally stealing a baby, which was never seen again, the blacks having roasted it for the camp's dinner. After a time he left for Melbourne. While here he met the same tribe of blacks, who recognised him, although the years had passed in the interim.”

Martha, our great great grandmother, born in 1850, was the first of eleven of Adam and Elizabeth’s children to be born in Australia.

The family moved to Broadmeadows, where Adam worked as a farm hand, cutting thistles and maintaining fences, as well as farming a piece of land himself. The newspaper article mentions wheat, potatoes and onions.

Here is an extract about the Broadmeadows farm.

He had about 2 acres of and with a splendid crop of onions on it. He and his family had been working hard getting these ready for market and left them in heaps about the ground ready to bag next day. To their utter astonishment, on going to finish their work they found that somebody had done the work for them, and had carted the lot away. There were from 10 to15 tons altogether, and this at £8 a ton was no small item to lose. However, he made up a bit on his crop of potatoes, which, although a light one, brought in £30 a ton. Butter was then 3 shillings a pound, bread 1 shilling a loaf, and a bag of flour as high as £5 a bag. This was owing in a good measure to the high rate of cartage.

This was the height of the gold rush, and Adam was not exempt from gold fever. In this story the “Black Forest” is mentioned. We found that it was an area near Mt Macedon, and part of a common route to the gold fields.

He had only one experience at mining and that when the Bendigo rush broke out. He with about a party of 20 shouldered their swags and tramped to Bendigo. In crossing through the Black Forest, as it was then called, they met with Black Douglas—a famous bushranger of he time. The party had just camped for the night when Douglas and men—numbering six—came on them. The party were all armed with guns and warned the rangers not to come any closer or they would fire. The robbers only had revolvers so thought it best to do as they were told. They, however, tried a couple of times during the night, but the miners were always ready for them and at last Douglas came to the conclusion it was no use trying again. The bushrangers would have had a fair haul if they had succeeded as each man was carrying a tidy sum of money at the time. Rye didn't do any good there although as he says it was a poor man's diggings all right, as gold was found on many occasions only a few feet from the surface. Everyone who could possibly follow the rushes went, and labourers of all kinds were very hard to get. In some instances if you went to an hotel for a meal you would be told that you'd have to cook it yourself if you wanted it, the cook having caught the gold fever and gone off. Farmers were in sore straits for men at harvest time and wages went up in a very short time from 10s to £4 a week. Finding the diggings no good to him Rye made his way to Colac, where farm labourers were badly wanted, and earned as much as £1 a day trussing hay.

We have ascertained that this move to Colac happened abut 1873, long after Martha had married Joachim Dau. Adam worked for a time as a farm hand and also a road builder.

At the time of this article, Adam was in his nineties. Elizabeth had died many years earlier. At that time he was living in Benalla with another of his daughters.

The old man dearly loves a game of euchre, and takes a very keen and intelligent interest in the game. In the summer months it was not uncommon sight to see him sitting out under the trees reading his Bible and prayer-book.

He died on his 102 birthday. Interestingly Alice and Marge tell the story of his death, but they remembered it as being about Joachim, Adam’s son in law and our great great grandfather. Joachim died in his eighties.

Alice says “and he died on his one hundred and second birthday, sitting up in bed and singing a hymn.” That definitely fits the facts and the personality of Adam Rye.

He is buried in the Benalla cemetery.

Adam and Elizabeth (both seated) with family members:

These early pioneers were the parents of the “unknown” girl in the market, “dragged away” to the farm in Wandong by the older German man. Marge and Alice knew nothing of their colourful lives.

Nor did they know anything about their great grandfather. “there was “some evidence of a high class family, ….. the Von Dows of Bavaria.”

In fact Johann Joachim Ties Dau was born in 1832 in Bukowko, (Neu Buckow in German) in present day Poland. His parents were Gottlieb and Anna. Their town, which they would have called Bukówko, was part of Pomerania, in present day Poland. Situated in what is known as the “Polish Corridor”, over the centuries Bukowko has also been part of Sweden, The Holy Roman Empire, Denmark, Prussia,, France (Napoleon) and East Germany.

Johann arrived in Australia during the 1850s with his wife, Maria (born Maria Winter), who was from the same town and six years younger. The couple acquired a farm at Wandong, near Kilmore.

In 1861 a child, Eliza, Louisa Dau was born. Maria died in childbirth. The baby lasted only a year before it too died.

So in 1865, the thirty-three year old Johann had suffered his wife’s death four years earlier, and his baby daughter, three years ealier.

……….

Now you have the facts and the family tale. We have the knowledge that our roots go back to the very early days of the Colony of Victoria and that the lives of these early settlers were touched by many of the events we read about in history books, including the Gold Rush, bushrangers and encounters with ‘the blacks’.

The immigrants, Martha's parents and husband came from England and Poland as young people looking for a new life.

Martha herself, an older child in a family of twelve children would have helped her mother both with daily tasks and the younger children. She was also according to the tale helping her father sell the produce from their small plot: not an easy life for a fifteen year old girl but probably not uncommon.

Was the older man (actually in his prime at only 33) at the market a good proposition? Was it the Victoria Market or one of the many local markets in the colony? After all Broadmeadows was the country then. Johann had lost his wife and child soon after they arrived in the colony and he owned a farm at Wandong, probably bigger than her father’s small rented plot in Broadmeadows. Did she take a chance, strike out on her own and opt for a better life?

We will never know but she and Johann produced 18 children many of whom also went on to lead colourful lives.

Poor little thing ????