Heather Farm, Kilmore Junction ,1879

Sarah Dau aged 8, and two of her sisters, photographed in 1874.

Fifty Years Ago at Kilmore Junction HEATHER FARM

In a lonely spot on the hillside, where the old cypress still lives and bends in the breeze, stands what is left of our once loved home, so loved in those old days gone by when a dear father and mother still lived to help us unravel life's tangled skein.

There the musk tree, mother planted, and cared for and loved—just beside the straggling remains of the lovely lilac trees; there the remains of the old gum tree where father sharpened his axe in its groove, and we children watched and wondered what difference it made; the path where the strawberries grew large and juicy on each side; the vines and the currants and gooseberry bushes—what tales they could tell could they speak. Father's pear tree, once laden with its golden store, now old and scrubby, still fading away.

The dairy house still stands, but the hum of the separator is silent. The stable, where Polly and Lofty enjoyed their hard-earned rest and feed, the cow yards: oh, what memories of Blossom, Violet and Peggy do those few remaining stone paths recall.

There is the old slip-panel, where father stood to welcome the children with smiling face when home on holiday: dear, gentle Dad, from whose lips we heard no unkind word; the wild cherry tree, where the boys carved their names, still there, the same beloved handwriting, although one sleeps in France and the other in Africa—duty nobly done.

The corner where the raspberries grew, juicy and red, at Xmas time; our favourite apple tree. How we loved to run down and see how many our thoughtful mother had saved for us, her wanderers. Memories!

Sometimes we wander back again to where the old home stood, and as we stand and think of other happy days gone for ever and gaze on all this, we seem to hear their loved voices again speaking to us, their children, although some of us are on the shady side of 60.

What would we give to live some of those old times gone by, and a kind word from father and a smile from mother? Seventeen of us—their children—were reared up to manhood and womanhood on the site of that once beloved home. The silent bush: no picture shows, no evening entertainments, just our books and our church on Sunday.

Oh, to live it all again. To once more call dear old Blossom, Peggy, and Strawberry home for milking. To feed again those poddy calves. To turn the old separator. To hear the voice again of our dear old teacher—who taught 13 of our family before he went to rest. To walk to the old church on Sundays and then home, where mother had laid the snow cloth with all things good for tea (and home made), and then go to the back paddock for wattle gum, where the pink and white heath grew, and wattle blossom bloomed.

Dear old home, we shall never see again. Only in our memory there will live that lovely past, which for us all, too soon, has fled and left only memories of other days. Some of us would love to live again at dear old Heather Farm.

Sarah Coles (née Dau)

McEwan Road, Heidelberg. 7/2/1929

The Poor Little Thing

Marge and Alice, with great drama, tell the story of our great, great grandmother whose name they do not know, and her subsequent marriage to Grandfather Dow, with whom she had eighteen children.

They had little factual information and their story is obviously based on stories told to them by their father. “That’s how the tale goes and the imagination boggles,” says Alice at one stage and indeed it did!

THE FAMILY TALE would have us believe that the our great, great grandmother, name unknown, met her prospective husband, first name unknown, at the Victoria Market. She was apparently a child of fifteen dragged off by a middle aged man to a poor farm miles out in the country of early colonial Victoria. The long and arduous journey into the night finished at Wandong where the poor little thing, ‘rolled up her sleeves and started milking cows straight away.’ She bore eighteen children and did much of the work, as her husband, a German immigrant from Bavaria, who was rumoured to have noble blood, sat behind the milking shed reading poetry. The poor little thing lived to 83 and grew very broad in the beam. Her husband as the tale goes died at 102 sitting up in bed singing a hymn.

The mind does indeed boggle. Was she a poor little thing? How much is ‘tale’?

You be the judge.

We also have a story extrapolated from FACTS provided by the Victorian Records Office, Ancestry Dot Com, Google, newspapers, shipping records and documents from England.

The ‘poor little thing’ was Martha Rye born in 1850 in Geelong in the Colony of New South Wales. The year after her birth in 1851 the Colony of Victoria was founded and separation from New South Wales was formalised.

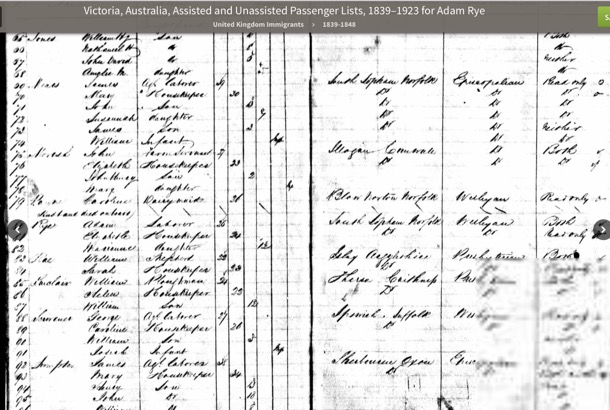

Martha Rye was the first child born in Australia to Adam (1822 - 1924) and Elizabeth (1824 - 1901) Rye, recently arrived immigrants to the young colony.

Adam and Elizabeth emigrated to Australia from South Lopham in Norfolk, England in 1848. They had with them one child, Marianne who was a year old. Adam was twenty-six and Elizabeth twenty-four.

Here is the South Lopham church in which they were married:

We know from the shipping records that they sailed on the sailing ship The Berkshire, arriving in Geelong on October the third, 1848. Their occupations were listed as labourer and housekeeper. He could read and write, she could read but not write.

We know that he had indeed worked as a labourer on his father’s farm, but he had also had a stint as a footman in the household of Lord Randall, which is where he tasted a bit of Queen Victoria’s wedding cake, shared with the staff by Lord Randall, who had been a wedding guest.

When he and Elizabeth left for Australia, they sat down to a farewell dinner with thirty-two of Adam’s brother and sisters (from three different mothers).

Adam lived 102 years, and when he was in his nineties, his colourful life story was written up by an enthusiastic journalist for a local paper. Note his editorialising in the following extract about “treacherous blacks”.

The family settled near Geelong, where they rented a piece of land to farm.

“While here Rye went off one day to the store for provisions, and after getting his supplies started for home, but darkness overtook him and he lost the track. He wandered about for some hours, and at last came upon a party of about 50 blacks. He thought it was no use trying to run away so he had to stand his ground. The blacks took his supply of bread, cheese, tobacco and a bottle of rum away from him and divided them amongst themselves, never leaving him a bite. Towards morning he made them understand where he lived and they directed him to his home, but having found out where he lived they paid him a couple of visits at night time and carried off his potatoes - not any that came to hand but the biggest and best and potatoes were worth £30 a ton in those days. The blacks at this time were very treacherous. They would watch the mothers going away for water and would steal into the huts and carry away anything they fancied even occasionally stealing a baby, which was never seen again, the blacks having roasted it for the camp's dinner. After a time he left for Melbourne. While here he met the same tribe of blacks, who recognised him, although the years had passed in the interim.”

Martha, our great great grandmother, born in 1850, was the first of eleven of Adam and Elizabeth’s children to be born in Australia.

The family moved to Broadmeadows, where Adam worked as a farm hand, cutting thistles and maintaining fences, as well as farming a piece of land himself. The newspaper article mentions wheat, potatoes and onions.

Here is an extract about the Broadmeadows farm.

He had about 2 acres of and with a splendid crop of onions on it. He and his family had been working hard getting these ready for market and left them in heaps about the ground ready to bag next day. To their utter astonishment, on going to finish their work they found that somebody had done the work for them, and had carted the lot away. There were from 10 to15 tons altogether, and this at £8 a ton was no small item to lose. However, he made up a bit on his crop of potatoes, which, although a light one, brought in £30 a ton. Butter was then 3 shillings a pound, bread 1 shilling a loaf, and a bag of flour as high as £5 a bag. This was owing in a good measure to the high rate of cartage.

This was the height of the gold rush, and Adam was not exempt from gold fever. In this story the “Black Forest” is mentioned. We found that it was an area near Mt Macedon, and part of a common route to the gold fields.

He had only one experience at mining and that when the Bendigo rush broke out. He with about a party of 20 shouldered their swags and tramped to Bendigo. In crossing through the Black Forest, as it was then called, they met with Black Douglas—a famous bushranger of he time. The party had just camped for the night when Douglas and men—numbering six—came on them. The party were all armed with guns and warned the rangers not to come any closer or they would fire. The robbers only had revolvers so thought it best to do as they were told. They, however, tried a couple of times during the night, but the miners were always ready for them and at last Douglas came to the conclusion it was no use trying again. The bushrangers would have had a fair haul if they had succeeded as each man was carrying a tidy sum of money at the time. Rye didn't do any good there although as he says it was a poor man's diggings all right, as gold was found on many occasions only a few feet from the surface. Everyone who could possibly follow the rushes went, and labourers of all kinds were very hard to get. In some instances if you went to an hotel for a meal you would be told that you'd have to cook it yourself if you wanted it, the cook having caught the gold fever and gone off. Farmers were in sore straits for men at harvest time and wages went up in a very short time from 10s to £4 a week. Finding the diggings no good to him Rye made his way to Colac, where farm labourers were badly wanted, and earned as much as £1 a day trussing hay.

We have ascertained that this move to Colac happened abut 1873, long after Martha had married Joachim Dau. Adam worked for a time as a farm hand and also a road builder.

At the time of this article, Adam was in his nineties. Elizabeth had died many years earlier. At that time he was living in Benalla with another of his daughters.

The old man dearly loves a game of euchre, and takes a very keen and intelligent interest in the game. In the summer months it was not uncommon sight to see him sitting out under the trees reading his Bible and prayer-book.

He died on his 102 birthday. Interestingly Alice and Marge tell the story of his death, but they remembered it as being about Joachim, Adam’s son in law and our great great grandfather. Joachim died in his eighties.

Alice says “and he died on his one hundred and second birthday, sitting up in bed and singing a hymn.” That definitely fits the facts and the personality of Adam Rye.

He is buried in the Benalla cemetery.

Adam and Elizabeth (both seated) with family members:

These early pioneers were the parents of the “unknown” girl in the market, “dragged away” to the farm in Wandong by the older German man. Marge and Alice knew nothing of their colourful lives.

Nor did they know anything about their great grandfather. “there was “some evidence of a high class family, ….. the Von Dows of Bavaria.”

In fact Johann Joachim Ties Dau was born in 1832 in Bukowko, (Neu Buckow in German) in present day Poland. His parents were Gottlieb and Anna. Their town, which they would have called Bukówko, was part of Pomerania, in present day Poland. Situated in what is known as the “Polish Corridor”, over the centuries Bukowko has also been part of Sweden, The Holy Roman Empire, Denmark, Prussia,, France (Napoleon) and East Germany.

Johann arrived in Australia during the 1850s with his wife, Maria (born Maria Winter), who was from the same town and six years younger. The couple acquired a farm at Wandong, near Kilmore.

In 1861 a child, Eliza, Louisa Dau was born. Maria died in childbirth. The baby lasted only a year before it too died.

So in 1865, the thirty-three year old Johann had suffered his wife’s death four years earlier, and his baby daughter, three years ealier.

……….

Now you have the facts and the family tale. We have the knowledge that our roots go back to the very early days of the Colony of Victoria and that the lives of these early settlers were touched by many of the events we read about in history books, including the Gold Rush, bushrangers and encounters with ‘the blacks’.

The immigrants, Martha's parents and husband came from England and Poland as young people looking for a new life.

Martha herself, an older child in a family of twelve children would have helped her mother both with daily tasks and the younger children. She was also according to the tale helping her father sell the produce from their small plot: not an easy life for a fifteen year old girl but probably not uncommon.

Was the older man (actually in his prime at only 33) at the market a good proposition? Was it the Victoria Market or one of the many local markets in the colony? After all Broadmeadows was the country then. Johann had lost his wife and child soon after they arrived in the colony and he owned a farm at Wandong, probably bigger than her father’s small rented plot in Broadmeadows. Did she take a chance, strike out on her own and opt for a better life?

We will never know but she and Johann produced 18 children many of whom also went on to lead colourful lives.

Poor little thing ????

Our Little Allie 1895-1906

Late July 2007, on a clear winters day in Chiltern, a small Northern Victorian town I found myself standing by my great aunt’s graveside. Alice Martha Coates died on the 8th of October 1906, aged eleven and a half.

Thomas and Tessa had just been married at Nagambie and we were heading up the Hume Highway for a little R & R with Anne and Ben in the vineyards of Rutherglen. As we approached the turn off to Chiltern, 38k past Wangaratta where my grandfather Alfred had lived as a boy, we decided to have an ‘explore’. We turned towards Chiltern and found ourselves in the historic main street, complete with restored shopfronts, antique shops and the Historical Society, open for business.

Margaret and I, aware that our mother had been named after her, had grown up hearing our grandfather talk in hallowed tones of ‘our little Allie’ who, in our childhood memories, was almost saint like. You must remember that Margaret and I had grown up on a diet of novels such as Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, one of our favourites. In this novel Beth March, a child almost too good to be true and therefore likely not long for this world dies a lingering but saintly death, nursed by her adoring older sister. Fertile imagination conjured up such scenes as we heard the stories of little Allie's death or held the remembrance badge portraying her as a pretty, serious child. Allie died at Chiltern but that was all I knew, so into the Historical Society to find out more.

The building was slightly musty, its walls covered in old photographs and fortunately for us, as is so often the case, it was staffed by an enthusiastic and knowledgable volunteer. Yes, he knew about Reverend Alfred Coates : We think he lived in this house and yes his youngest daughter died here. After rummaging in the filing cabinet we had the location of the grave in the Chiltern Cemetery and we were able to read a newspaper report on the well attended funeral. Alice had obviously been ill for several weeks and it was no doubt a big topic of conversation in the town, especially as she was the daughter of a much loved Pastor. Maybe other children in the town were also ill in those same weeks.

Who was Alice Martha Coates, our great aunt who died aged eleven?

Our grandfather’s parents were Alfred senior, a Methodist parson, and Emma. The church chose his positions and moved the family every three years, in their case throughout country Victoria. They had four children, Florence, Alfred (our grandfather), Alice and Arthur. The photographs below show Allie with her parents and their house in Chiltern.

Allie died from the disease Diphtheria. This was a very common childhood disease of the times. Nowadays we have a vaccine for it, and antibiotics to treat it, but in those days it was one of the most feared childhood diseases.

It was highly contagious, and Emma and Alfred must have been very worried about the other children catching it. At first the symptoms are like those of a cold, but a horrible film, like a spider web, grows on the back of the throat or in the nose, and makes it hard to breathe. Alice must have had a really bad dose, because only one in ten people over five died from Diphtheria.

Armed with directions to the cemetery we politely extracted ourselves before we heard the complete history of Chiltern and stepped outside into the twenty-first century world. The cemetery is located outside the now small town, in slightly undulating country. It was chilly that day but this small country cemetery would have seen many blistering hot summer days. My thoughts turned to my grandfather: Allie’s older brother Alf, standing with his family at the graveside during the funeral. Some memories were no doubt already etched in his memory and others were forming These would combine to become the story of this tragic event passed down to us.

The little remembrance badge of Allie (shown below) lived in a wooden box on Alf’s desk. As children, we drank in the pathos of her beauty and goodness, amplified by the Victorian novels we read. The telling and retelling of little Allie’s story first by our grandfather and then our mother and aunt has helped Allie’s story retain its enduring poignancy, lifting it out of the commonplace into the world of idealised tragic heroines.

Allie’s grave is indeed in the Chiltern Cemetery, still intact. The modest headstone is there surrounded by the typical wrought iron fence of the era. The only flowers are those of the Cape Weed Daisies growing in abundance throughout the cemetery. The inscription is still legible and simply reads: Our Allie October 8th 1906. As I stood there the story suddenly seemed much more real. Allie was no longer the tragic heroine, but a little girl who died an unpleasant death, mourned by her distraught family.

I picked a small bunch of the Cape Weed daisies and placed it front of the headstone.