The Pakenham Bourkes 1839 - 2017 Part One.

19 04 17 14:58 Filed in: Jim

Michael and Catherine Bourke of County Limerick, Ireland, our great great grandparents were part of the very early settlement of Victoria. They were sponsored as assisted migrants.

New South Wales had been settled as a convict colony in 1788, when the first fleet arrived. Over the next fifty years, many convicts were transported there, and many English free settlers chose to try their luck in that distant land. By the 1830s, there was clearly a need for more immigrants in the colony. Not only was there three men to every woman, but the balance of convicts to free settlers was all out of whack. There were not enough reliable trustworthy labourers to work on all the properties that had been developed, especially all the sheep stations.

A committee was set up to address this issue. It looked like a win-win situation with England, where the population had outgrown the jobs available, especially in the country. It should have been easy to entice the right kind of working people to settle in New South Wales. But America was also expanding, and was a fifth of the distance. It was hard to persuade people to undertake a perilous sea voyage to New South Wales instead.

A scheme was set up whereby young country women of good character would have their sea passage paid for and be guaranteed a job as a servant in rural New South Wales.

Predictably the people whose task was to head off into the countryside and interview young unmarried women of good character, took shortcuts, and, by the sound of it, simply herded up the “mere sweepings of the streets of London” who were all too happy to take the money.

On one large ship, the David Scott, 226 single females came out to New South Wales. Mr Marshall, Royal Navy, the hapless “superintendent” of the ship said of the 226 “there were not more than twenty-five that I would consider suited for country servants”. Furthermore the David Scott was a very large ship and there were more than fifty men in the crew. They seemed to have been totally out of control ‘they .. had unrestrained intercourse with them during the voyage” (in this context ‘intercourse’ just means anything from unsupervised conversation to what it means today) ‘I do not allude of course to the whole of the women, but to upwards of forty of them, whose abandoned and outrageous conduct kept the ship in a continual state of alarm during the whole passage’

The committee overseeing this scheme were supposed to have “personally questioned every female for the purpose of ascertaining her age, occupation and qualifications in other respects for the colony. Either the powers of dissimulation (lying) possessed by abandoned females of the lowest grade must be very great indeed and must be well backed by forgery, or the gentlemen of the London committee must have been marvellously unskilled in discriminating character.”

After this debacle only small ships were used, and many other checks and balances were put in place, including the selection of potential migrants. It is in this context that, in 1838, Governor Richard Bourke contacted his friend, Thomas Spring -Rice, Baron of Monteagle, and landlord to young Michael Bourke of Foynes Island Shanagolden, County Limerick, Ireland.

Governor Bourke asked Spring-Rice to carefully select suitable people to participate in a scheme to emigrate to New South Wales, and, in particular, the newly colonised area of Port Phillip. In 1839 13 families who had been Spring-Rice’s tenants, including Michael and his new wife Catherine, emigrated to Australia on the Aliquis. Most settled in the Port Phillip area. By 1858, about 800 ‘Monteagle emigrants” had settled in the new colony.

Monteagle county in New South Wales, containing the towns of Forbes and Bathurst, is named after this Irish nobleman.

So Michael and Catherine Bourke, our Irish great great grandparents and founders of the Australian branch of the Bourke family, arrived in Australia on St Patricks Day, March 17th in 1839.

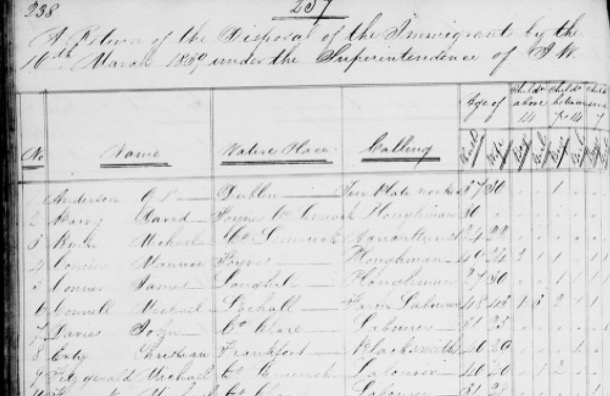

On the ship's list Michael, 24, is listed as an “agriculturalist”, with his unnamed wife aged 22, though perhaps she was only 20. Catherine had in fact been a dairy maid back in Limerick.

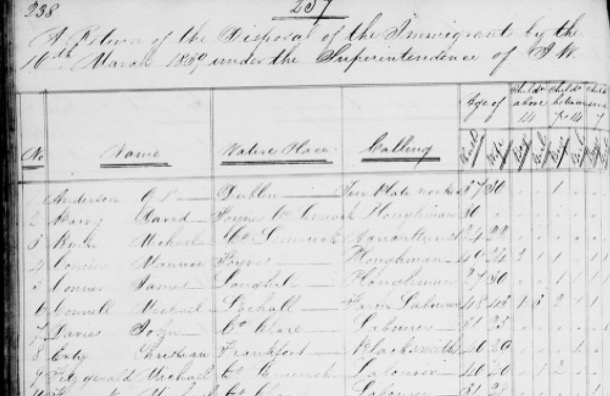

Close up of the Aliquis passenger list. Michael Bourke (misspelt as Burke) third on the list.

In an interview carried out when Catherine was a very old lady she said that they were married in Cork City, just before they left for New South Wales on the ship Aliquis,

And yet, when they arrived at Sydney, on March 2nd 1839, Michael and Catherine lost no time in seeking a priest to bless their marriage, and on Saint Patrick’s day, the ‘Banns of Marriage’ were read for the first time. It was at St Mary’s cathedral in Sydney where, 22 days later, the couple made their Vows of Marriage, on April 8th before Fr Francis Murphy and their friends from their home parish of Shanagolden, who had traveled with them from Ireland.

Work in Sydney was scarce and the ship John Barry took them along with most of their fellow travellers to the newly laid out town of Melbourne. Michael and Catherine spent their early days in Moonee Ponds, managing a dairy farm. The first three sons, James, John and Thomas were born there.

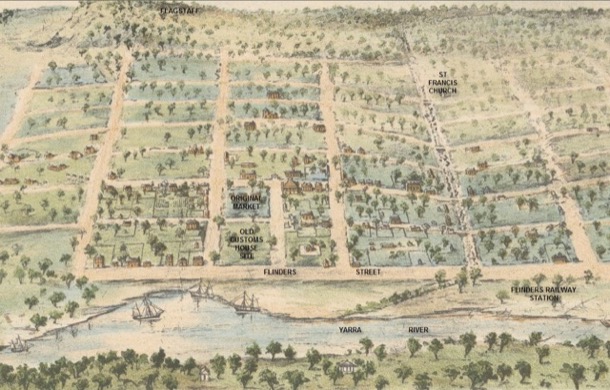

Just four years before Michael and Catherine Bourke arrived in what was then the Colony of N.S.W. Melbourne had begun its ramshackle development. John Batman, entrepreneur and settler, signed a treaty with aboriginal occupants of the Port Philip District, the Kulin nation. He promptly claimed over 500,000 acres north and west of present day Melbourne and also famously declared the present site of Melbourne’s CBD, as the place for a village. The then Governor of the Colony of NSW, Governor Bourke, became concerned at the unruly and illegal occupation of land and took charge, declaring all settlements invalid. He appointed Captain Lonsdale to represent him and run the settlement of Port Philip. Fees for grazing rights to squatters were imposed and Governor Bourke approved Hoddle’s plan for the streets of Melbourne. This is new world which Michael and Catherine entered as they stepped off the boat to begin their new life.

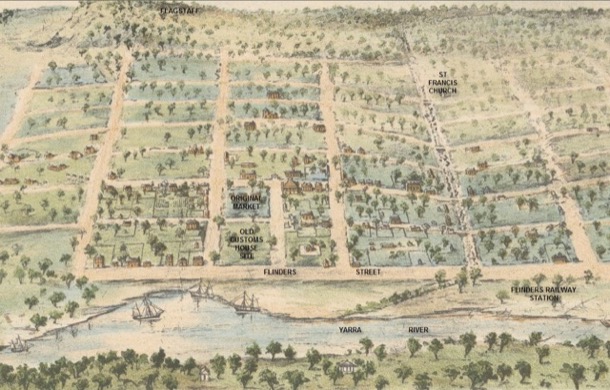

Hand drawn map of very early Melbourne, around 1837

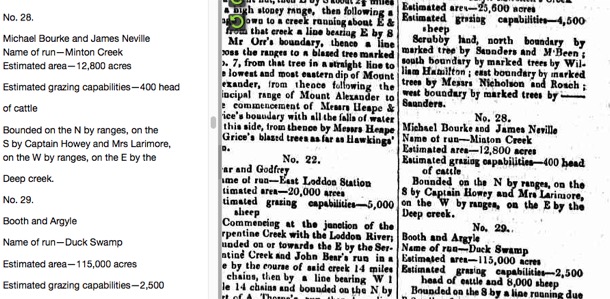

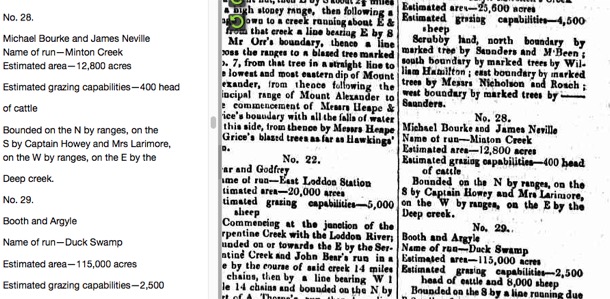

The family moved to near Pakenham in 1844, with their friends the Nevilles, who had come out on the Aliquis with them from Limerick. Under the partnership names of Neville and Bourke, they settled in the Toomuc Valley area, taking up the “Minton’s Creek” run, which extended towards Upper Beaconsfield, 12,800 acres, about 5 square kilometres. Here, our great, great grandfather, Michael, was born in their ‘slab hut’ home in 1844.

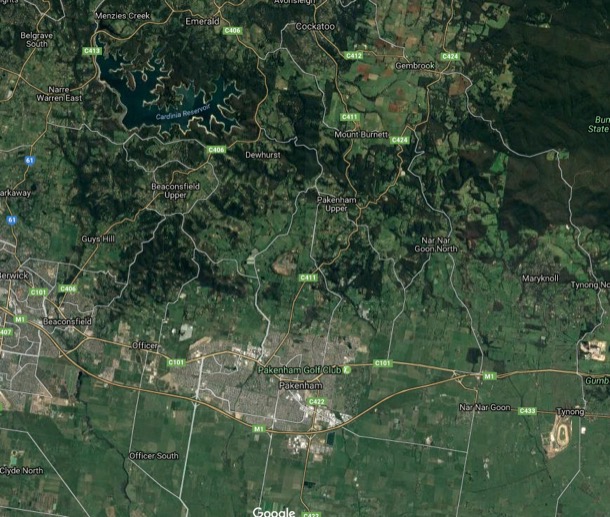

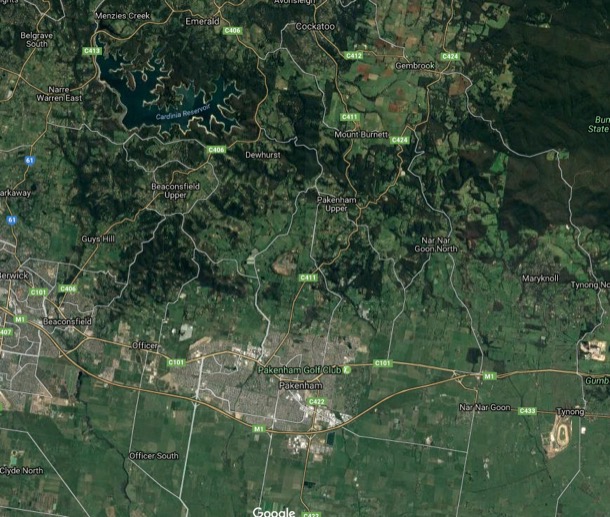

Minton's Creek Run covered the whole of present day Pakenham Upper

The Minton's Creek house site was in the centre of this aerial photo

In 1850, the Bourkes bought the Latrobe Inn, a hotel on the main Gippsland Road, where the Toomuc Creek (also known as Bourke’s Creek) crosses the main road. It became known as Bourke’s Hotel. Catherine and the seven children they had by then moved to the hotel to manage it, while Michael stayed at the station.

Bourke's hotel

Only the original chimney stands today.

n February, 1851, after a prolonged drought, a massive bushfire covered a quarter of what is now Victoria. The smoke blew on strong hot winds, wreathing Northern Tasmania in thick smoke. It became known as Black Thursday. The story goes that Michael fought the blaze, first with water, and then milk from the dairy.

Word reached him that the hotel itself was surrounded by fire. He galloped down to Pakenham and there he found that Catherine and the children had hidden in the Toomuc Creek bed and escaped the blaze, and that the hotel itself had not burnt.

from Black Thursday, a painting in the State Library

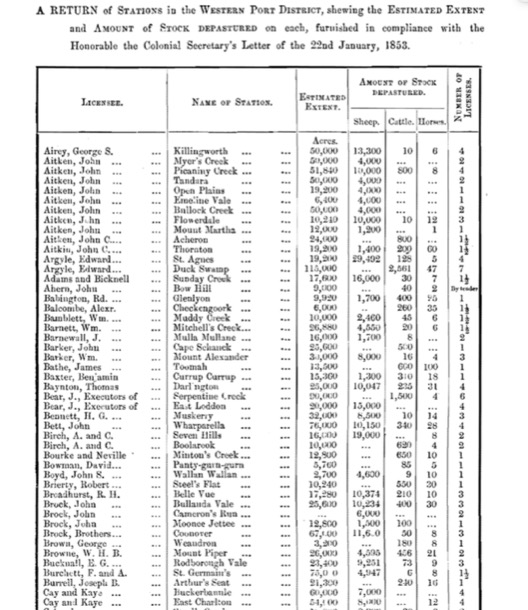

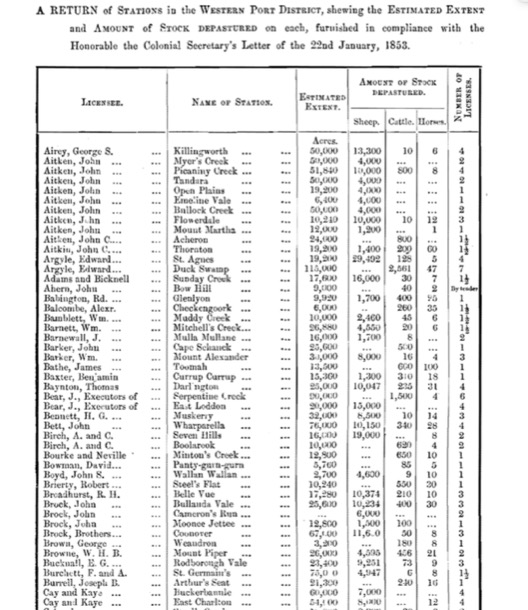

They restocked the property and in an 1853 census it was reported that Bourke and Neville had 650 cattle and ten horses on their 12,800 acres.

Bourke’s Hotel became one of the best known stopping places on the way to Gippsland. Later it became the Princes Highway Hotel and its chimney is still there today.

It was a real hub of the district. It was the polling station and the post office for the area, and Michael Bourke was postmaster at Pakenham for 30 years, and after his death, in 1877, Catherine and unmarried daughter Cecelia continued to run the post office.

In his 1942 book Memoirs of a Stockman, Harry Huntington Peck wrote:

Old Mrs. Bourke who was the landlady of the Pakenham hotel at the bridge over the Toomuc creek for so many years was an institution of the district. She was most popular with the Gippsland travellers and drovers as she took pains to make all visitors comfortable. Her fine sons David and Daniel prospered as graziers and bought good properties, the one Llowalong originally part of Bushy Park on the Avon near Stratford, and the other Old Monomeith, where the next generation Hughie and Michael, trading as Bourke Bros., are today the largest regular suppliers of baby beef to Newmarket, are well known as the owners of show teams of first-class hunters and hacks, and of late years, have been very successful in principal hurdle and steeplechase races.

It was at Bourke’s Hotel that the remainder of the children were born. There were fifteen in all, but two died in infancy.

Gradually the family grew to adulthood, and, when large areas of land were thrown open for “selection”, all the boys in turn gained properties.

Some of them are still in the hands of their descendants.

New South Wales had been settled as a convict colony in 1788, when the first fleet arrived. Over the next fifty years, many convicts were transported there, and many English free settlers chose to try their luck in that distant land. By the 1830s, there was clearly a need for more immigrants in the colony. Not only was there three men to every woman, but the balance of convicts to free settlers was all out of whack. There were not enough reliable trustworthy labourers to work on all the properties that had been developed, especially all the sheep stations.

A committee was set up to address this issue. It looked like a win-win situation with England, where the population had outgrown the jobs available, especially in the country. It should have been easy to entice the right kind of working people to settle in New South Wales. But America was also expanding, and was a fifth of the distance. It was hard to persuade people to undertake a perilous sea voyage to New South Wales instead.

A scheme was set up whereby young country women of good character would have their sea passage paid for and be guaranteed a job as a servant in rural New South Wales.

Predictably the people whose task was to head off into the countryside and interview young unmarried women of good character, took shortcuts, and, by the sound of it, simply herded up the “mere sweepings of the streets of London” who were all too happy to take the money.

On one large ship, the David Scott, 226 single females came out to New South Wales. Mr Marshall, Royal Navy, the hapless “superintendent” of the ship said of the 226 “there were not more than twenty-five that I would consider suited for country servants”. Furthermore the David Scott was a very large ship and there were more than fifty men in the crew. They seemed to have been totally out of control ‘they .. had unrestrained intercourse with them during the voyage” (in this context ‘intercourse’ just means anything from unsupervised conversation to what it means today) ‘I do not allude of course to the whole of the women, but to upwards of forty of them, whose abandoned and outrageous conduct kept the ship in a continual state of alarm during the whole passage’

The committee overseeing this scheme were supposed to have “personally questioned every female for the purpose of ascertaining her age, occupation and qualifications in other respects for the colony. Either the powers of dissimulation (lying) possessed by abandoned females of the lowest grade must be very great indeed and must be well backed by forgery, or the gentlemen of the London committee must have been marvellously unskilled in discriminating character.”

After this debacle only small ships were used, and many other checks and balances were put in place, including the selection of potential migrants. It is in this context that, in 1838, Governor Richard Bourke contacted his friend, Thomas Spring -Rice, Baron of Monteagle, and landlord to young Michael Bourke of Foynes Island Shanagolden, County Limerick, Ireland.

Governor Bourke asked Spring-Rice to carefully select suitable people to participate in a scheme to emigrate to New South Wales, and, in particular, the newly colonised area of Port Phillip. In 1839 13 families who had been Spring-Rice’s tenants, including Michael and his new wife Catherine, emigrated to Australia on the Aliquis. Most settled in the Port Phillip area. By 1858, about 800 ‘Monteagle emigrants” had settled in the new colony.

Monteagle county in New South Wales, containing the towns of Forbes and Bathurst, is named after this Irish nobleman.

So Michael and Catherine Bourke, our Irish great great grandparents and founders of the Australian branch of the Bourke family, arrived in Australia on St Patricks Day, March 17th in 1839.

On the ship's list Michael, 24, is listed as an “agriculturalist”, with his unnamed wife aged 22, though perhaps she was only 20. Catherine had in fact been a dairy maid back in Limerick.

Close up of the Aliquis passenger list. Michael Bourke (misspelt as Burke) third on the list.

In an interview carried out when Catherine was a very old lady she said that they were married in Cork City, just before they left for New South Wales on the ship Aliquis,

And yet, when they arrived at Sydney, on March 2nd 1839, Michael and Catherine lost no time in seeking a priest to bless their marriage, and on Saint Patrick’s day, the ‘Banns of Marriage’ were read for the first time. It was at St Mary’s cathedral in Sydney where, 22 days later, the couple made their Vows of Marriage, on April 8th before Fr Francis Murphy and their friends from their home parish of Shanagolden, who had traveled with them from Ireland.

Work in Sydney was scarce and the ship John Barry took them along with most of their fellow travellers to the newly laid out town of Melbourne. Michael and Catherine spent their early days in Moonee Ponds, managing a dairy farm. The first three sons, James, John and Thomas were born there.

Just four years before Michael and Catherine Bourke arrived in what was then the Colony of N.S.W. Melbourne had begun its ramshackle development. John Batman, entrepreneur and settler, signed a treaty with aboriginal occupants of the Port Philip District, the Kulin nation. He promptly claimed over 500,000 acres north and west of present day Melbourne and also famously declared the present site of Melbourne’s CBD, as the place for a village. The then Governor of the Colony of NSW, Governor Bourke, became concerned at the unruly and illegal occupation of land and took charge, declaring all settlements invalid. He appointed Captain Lonsdale to represent him and run the settlement of Port Philip. Fees for grazing rights to squatters were imposed and Governor Bourke approved Hoddle’s plan for the streets of Melbourne. This is new world which Michael and Catherine entered as they stepped off the boat to begin their new life.

Hand drawn map of very early Melbourne, around 1837

The family moved to near Pakenham in 1844, with their friends the Nevilles, who had come out on the Aliquis with them from Limerick. Under the partnership names of Neville and Bourke, they settled in the Toomuc Valley area, taking up the “Minton’s Creek” run, which extended towards Upper Beaconsfield, 12,800 acres, about 5 square kilometres. Here, our great, great grandfather, Michael, was born in their ‘slab hut’ home in 1844.

Minton's Creek Run covered the whole of present day Pakenham Upper

The Minton's Creek house site was in the centre of this aerial photo

In 1850, the Bourkes bought the Latrobe Inn, a hotel on the main Gippsland Road, where the Toomuc Creek (also known as Bourke’s Creek) crosses the main road. It became known as Bourke’s Hotel. Catherine and the seven children they had by then moved to the hotel to manage it, while Michael stayed at the station.

Bourke's hotel

Only the original chimney stands today.

n February, 1851, after a prolonged drought, a massive bushfire covered a quarter of what is now Victoria. The smoke blew on strong hot winds, wreathing Northern Tasmania in thick smoke. It became known as Black Thursday. The story goes that Michael fought the blaze, first with water, and then milk from the dairy.

Word reached him that the hotel itself was surrounded by fire. He galloped down to Pakenham and there he found that Catherine and the children had hidden in the Toomuc Creek bed and escaped the blaze, and that the hotel itself had not burnt.

from Black Thursday, a painting in the State Library

They restocked the property and in an 1853 census it was reported that Bourke and Neville had 650 cattle and ten horses on their 12,800 acres.

Bourke’s Hotel became one of the best known stopping places on the way to Gippsland. Later it became the Princes Highway Hotel and its chimney is still there today.

It was a real hub of the district. It was the polling station and the post office for the area, and Michael Bourke was postmaster at Pakenham for 30 years, and after his death, in 1877, Catherine and unmarried daughter Cecelia continued to run the post office.

In his 1942 book Memoirs of a Stockman, Harry Huntington Peck wrote:

Old Mrs. Bourke who was the landlady of the Pakenham hotel at the bridge over the Toomuc creek for so many years was an institution of the district. She was most popular with the Gippsland travellers and drovers as she took pains to make all visitors comfortable. Her fine sons David and Daniel prospered as graziers and bought good properties, the one Llowalong originally part of Bushy Park on the Avon near Stratford, and the other Old Monomeith, where the next generation Hughie and Michael, trading as Bourke Bros., are today the largest regular suppliers of baby beef to Newmarket, are well known as the owners of show teams of first-class hunters and hacks, and of late years, have been very successful in principal hurdle and steeplechase races.

It was at Bourke’s Hotel that the remainder of the children were born. There were fifteen in all, but two died in infancy.

Gradually the family grew to adulthood, and, when large areas of land were thrown open for “selection”, all the boys in turn gained properties.

Some of them are still in the hands of their descendants.

blog comments powered by Disqus