The Demon Drink

Alcoholic drinks hardly ever entered our world. We were aware that the communion “wine” used by our own Presbyterian church was actually grape juice, which we approved of, and we knew that “Catholics” used real wine, which we didn’t approve of.

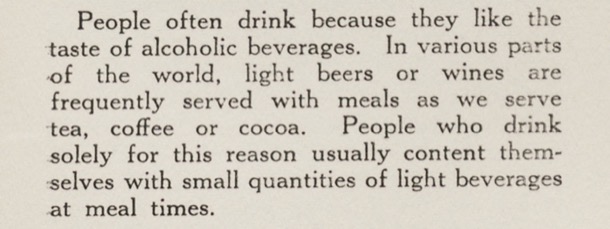

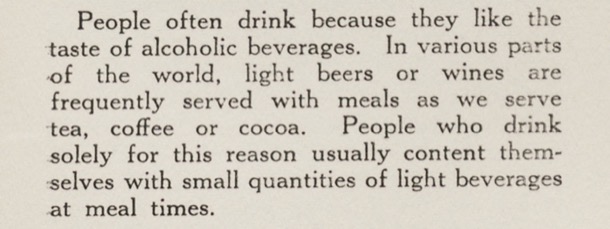

It was clearly uncommon for anyone in our narrow anglo world to drink at home. Here, for instance, is an extract from a Primary school resource book on Temperance from the 1950s.

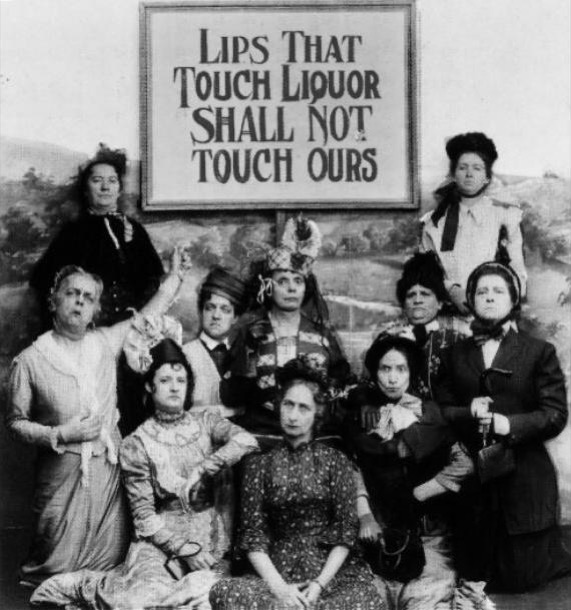

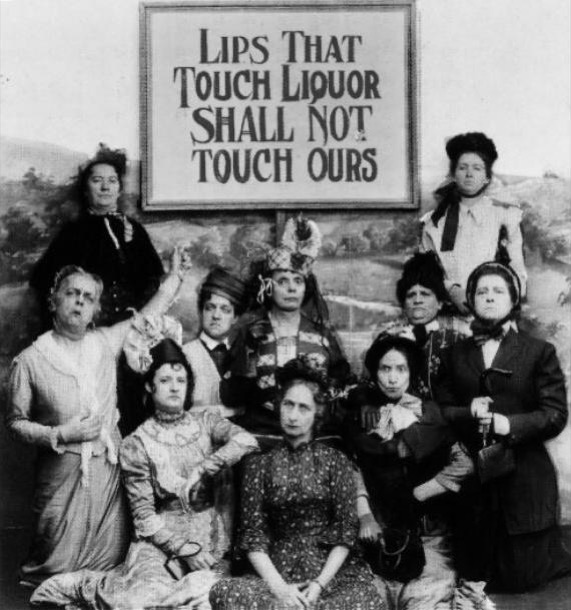

The international Temperance movement was one of the most powerful social movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Its advocates regarded alcohol as a social evil and sought to have it banned entirely, or at least its consumption drastically reduced.

Initially it was just a move against drinking spirits and “hard liquor". But during Victorian times it became more a push for total abstinence and became more specifically a women’s movement, connected with Protestant Christianity. Groups of women activists were to be found right across the western world.

The Temperance movement had its most obvious success in America, where the sale of alcohol became illegal across the whole country overnight in 1920.

This period of American history has become known as ‘Prohibition”, the Roaring Twenties. It conjures up images of gangsters, speak easies and moonshine. The law did not have the support of much of the population. But it wasn’t until 1933 that it was finally repealed.

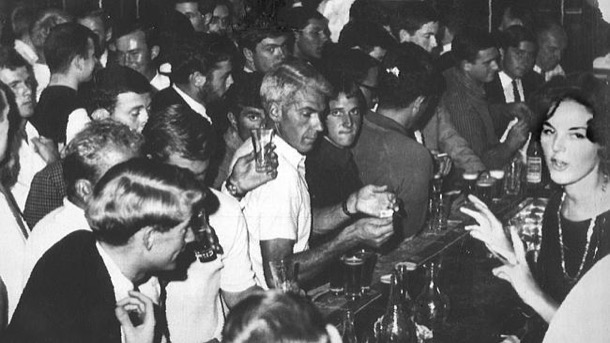

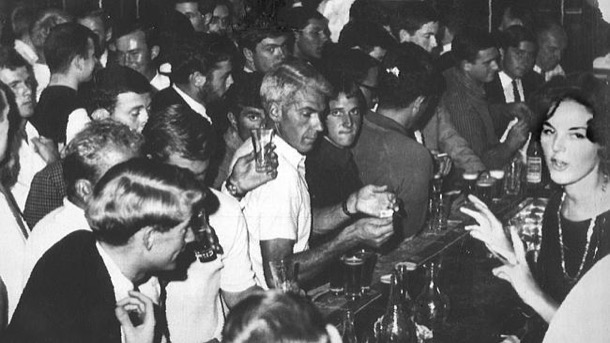

In Australia the temperance movement did not succeed in having the ‘demon drink’ banned but it did lobby vigorously for restriction of hotel opening hours. By 1923, hotel opening hours were restricted in all states. The closing of hotels at 6.00 PM led to a phenomenon known as the ‘Six O’clock Swill’.

It is hard to believe looking back that the daily rush to the bar was part of everyday life. Rather than limit drunkenness it actually encouraged it, as men who ‘knocked off’ work at 5 o’clock had only on hour in which to drink. Hotels were set up to serve as many beers as were demanded in this hour. Pubs were overcrowded, as men five or six deep lined the bar waiting to be served and patrons spilled out into the streets.

Pubs did smell strongly of beer as so much was served in such a short time. Sue can remember walking past Young and Jacksons on her way home and pushing her way through the throng of men, spilling out onto the pavement on the corner of Flinders Street and Swanston Street. Men, yes only men! Women were not permitted in the Bar until the early 1960s and for many years after that it was frowned upon. We can remember conversation stopping momentarily when we first walked into a bar particularly in the country.

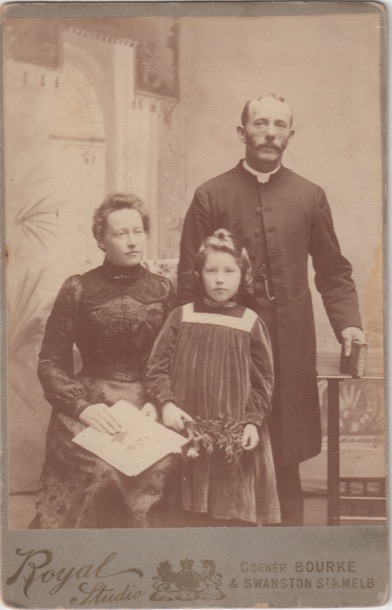

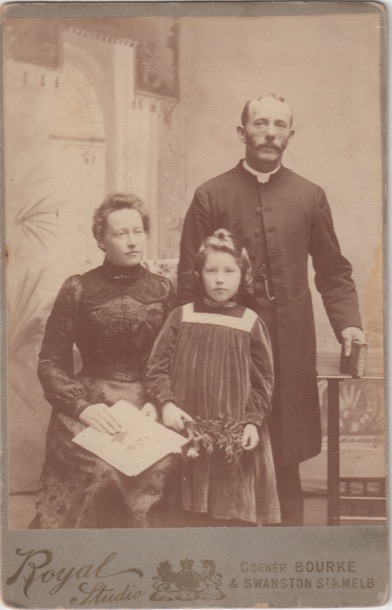

The Demon Drink indeed! We come from a long line of teetotallers: our great grandfather Reverent Alfred Coates, our great aunt Sister Bessie, our maternal grandparents, Alfred and Alfreda, their siblings and our parents. Our mother’s family, the Coates, being staunchly Methodist, we imagine would have been very sympathetic to the temperance agenda. Here is Alfred, in his Methodist pastor uniform with Emma and their daughter:

We were very aware as children that none of our family touched alcohol and that particularly frowned on by our rather upright Grandfather.

We too, at the tender age of eleven of twelve, have had our brush with The Independent Order of Rechabites, who provide educational material for Victorian Schools.

Alice and Marge as old ladies recounted their childhood memories of drunkenness, in the country town of Croydon during the 1930s, with obvious disapproval and distaste. Here they discuss the public drunkenness they witnessed at the hotel and wine hall near their house:

I remember our aunt having a glass of beer at the dinner table, when we were staying there as children. I commented on it and I remember being rebuked. Later our mother told me that it was medicinal, that she had found that drinking beer with food helped her digestion. That mum had felt the need to explain it that way, and that our aunt had reacted so strongly to a child’s interest is understandable in the light of heir own childhood experiences and family attitudes.

And then, during our late teens, as the 1960s became the 1970s, this part of our past just melted away. It became normal and natural too open a bottle of wine to share. There was binge drinking around us, especially at Uni parties, and the drink driving hazard was evident, but the moral dimension, the “holier than thou” attitudes, the raised eyebrow were all gone. Society had grown up about the same time that we did.

.

It was clearly uncommon for anyone in our narrow anglo world to drink at home. Here, for instance, is an extract from a Primary school resource book on Temperance from the 1950s.

The international Temperance movement was one of the most powerful social movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Its advocates regarded alcohol as a social evil and sought to have it banned entirely, or at least its consumption drastically reduced.

Initially it was just a move against drinking spirits and “hard liquor". But during Victorian times it became more a push for total abstinence and became more specifically a women’s movement, connected with Protestant Christianity. Groups of women activists were to be found right across the western world.

The Temperance movement had its most obvious success in America, where the sale of alcohol became illegal across the whole country overnight in 1920.

This period of American history has become known as ‘Prohibition”, the Roaring Twenties. It conjures up images of gangsters, speak easies and moonshine. The law did not have the support of much of the population. But it wasn’t until 1933 that it was finally repealed.

In Australia the temperance movement did not succeed in having the ‘demon drink’ banned but it did lobby vigorously for restriction of hotel opening hours. By 1923, hotel opening hours were restricted in all states. The closing of hotels at 6.00 PM led to a phenomenon known as the ‘Six O’clock Swill’.

It is hard to believe looking back that the daily rush to the bar was part of everyday life. Rather than limit drunkenness it actually encouraged it, as men who ‘knocked off’ work at 5 o’clock had only on hour in which to drink. Hotels were set up to serve as many beers as were demanded in this hour. Pubs were overcrowded, as men five or six deep lined the bar waiting to be served and patrons spilled out into the streets.

Pubs did smell strongly of beer as so much was served in such a short time. Sue can remember walking past Young and Jacksons on her way home and pushing her way through the throng of men, spilling out onto the pavement on the corner of Flinders Street and Swanston Street. Men, yes only men! Women were not permitted in the Bar until the early 1960s and for many years after that it was frowned upon. We can remember conversation stopping momentarily when we first walked into a bar particularly in the country.

The Demon Drink indeed! We come from a long line of teetotallers: our great grandfather Reverent Alfred Coates, our great aunt Sister Bessie, our maternal grandparents, Alfred and Alfreda, their siblings and our parents. Our mother’s family, the Coates, being staunchly Methodist, we imagine would have been very sympathetic to the temperance agenda. Here is Alfred, in his Methodist pastor uniform with Emma and their daughter:

We were very aware as children that none of our family touched alcohol and that particularly frowned on by our rather upright Grandfather.

We too, at the tender age of eleven of twelve, have had our brush with The Independent Order of Rechabites, who provide educational material for Victorian Schools.

Alice and Marge as old ladies recounted their childhood memories of drunkenness, in the country town of Croydon during the 1930s, with obvious disapproval and distaste. Here they discuss the public drunkenness they witnessed at the hotel and wine hall near their house:

I remember our aunt having a glass of beer at the dinner table, when we were staying there as children. I commented on it and I remember being rebuked. Later our mother told me that it was medicinal, that she had found that drinking beer with food helped her digestion. That mum had felt the need to explain it that way, and that our aunt had reacted so strongly to a child’s interest is understandable in the light of heir own childhood experiences and family attitudes.

And then, during our late teens, as the 1960s became the 1970s, this part of our past just melted away. It became normal and natural too open a bottle of wine to share. There was binge drinking around us, especially at Uni parties, and the drink driving hazard was evident, but the moral dimension, the “holier than thou” attitudes, the raised eyebrow were all gone. Society had grown up about the same time that we did.

.

blog comments powered by Disqus