"Cut out of the Will"

15 06 16 16:52 Filed in: Jim

Growing up we had heard many times how our father had been ‘cut out of the will’ by his father because he had married a Protestant and renounced the Catholic faith.

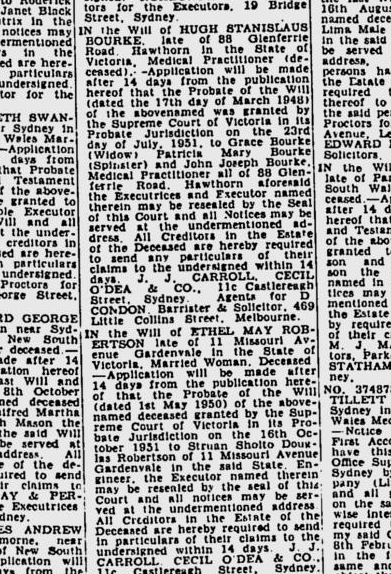

As we were researching the early life of our Catholic grandmother Grace, we stumbled across the application for probate for the will of Doctor Hugh Stanislaus Bourke, our grandfather. His widow Grace, his son Jack, his daughter Patricia are mentioned but no mention of James Vincent Bourke his second son, our father.

Here, published in the Argus Newspaper, was the brutal reality of what this divide really meant in our parent’s lives. It was no small sum: 36,353 pounds. In todays world this would be equivalent to leaving an estate valued at six and a half million dollars.

More shocking is the date, on which the will was written March 17, 1948: not when they married, but three years later, when Alice was only just pregnant with their first child who was not going to be raised as a Catholic. Was this the catalyst?

Australia and the Irish Catholic/English Protestant divide.

In the very earliest days of the NSW penal colony, many of the convicts and early settlers were Irish catholics, and most of the British Military, who ran the prison colony were Anglican protestants.

The first few decades of the colony coincided with unrest and rebellion in Ireland, which was still under English rule. The authorities were nervous of the very large numbers of Irish convicts and settlers, who spoke their own language and had a different religion.

Most of Ireland became a republic and a separate country in 1922. Although there was still unrest in Northern Ireland, which remains part of England to this day, most of the official heat went out of the Irish English divide, though it remained in people’s consciousness.

Australia had an influx of European migrants in the nineteen-forties and fifties, and gradually the clear division of Australian into Catholics and Protestants became blurred, though there was still institutionalised prejudice against Catholics, right up until the 1980s.

The other: the mysterious Catholic world seen through our eyes.

Dark, heavy wooden framed paintings of the Virgin Mary and the Crucified Christ were the mysterious evidence of the Catholicism of our grandmother. We only visited Grandma Bourke’s house three or four times a year for very formal, if delicious, afternoon tea. Our relationship with her too was very formal, a peck on the cheek hello and goodbye and no spontaneous hugs and signs of affection, as we saw our cousins receive.

We knew nothing of this strange Catholic world as we were Protestant and our parents were both heavily involved at St James Presbyterian Church, Wattle Park, where there were a few bare crosses, but no other iconography.

The dark religious ‘icons’ we saw in Grandma’s house were also to be found in Uncle Jack’s house in Glenferrie Road. Most mysterious was the large porcelain statue of Mary. Mother of God, clad in a pale blue robe and further upstairs another large porcelain statue of the Crucified and Risen Christ complete with bleeding nail holes. Gruesome stuff!

When we were growing up, even though we had Catholic relatives, we would never have gone into the Catholic Church. On several occasions we saw, at the local Catholic Church, little girls dressed up as Brides of Christ, lined up and waiting to process into the church for their First Communion.

Nuns in full habit were also very much part of our early memories. I remember back shiny lace up shoes visible under the long heavy black robes, the white starched wimple and veil and, above all, the clanking sound of the Rosary Beads and keys on a chain around their waists.

Even though, by the nineteen forties, there were Catholics in all walks of life, ordinary people still defined themselves and each other by whether they were Catholic or Protestant.

They went to separate schools, even at primary school level. If you went to a Protestant private school, you bought your uniform at Myers. Foys, another department store, catered for the Catholic ones.

Catholics were forbidden to set foot in a Protestant church. One story from this time is of the brothers of a Catholic woman marrying a Protestant forced to stand outside and watch the ceremony through the window. When Protestants and Catholics married it was called a “mixed marriage”

There was lots of name calling… “Micks”, “papists”, “proddy dogs”. Our father, attending the Catholic School in his home town of Koroit during the nineteen thirties, told us the story of him running home, chased by kids from the state school, turning and calling “proddy dogs, jump like frogs” or perhaps it was the others calling him a “Catholic dog” … probably both.

So when our father, Jim, told his Irish Catholic parents about his new girlfriend, there were probably alarm bells right from the beginning. Jim and Alice met at work, the Maribyrnong Munitions Factory.

They married in 1945, a couple of months before the end of the war. She did not dress as a bride, because it was still war time, and they had a quiet ceremony in the Congregational Church in Surrey Hills, near Alice’s home and a reception at Wattle Park Chalet.

The couple lived with her parents, Alfred and Alfreda, until they built and moved into their own house in the early nineteen fifties. Alice’s parents seem to have been very tolerant. Their eldest daughter had married a Hungarian Jew a few months earlier and now their other daughter, a Catholic. Theirs was a working class family, educated and valuing education, but without much money or position in society.

Jim’s parents were from a different class as well as a different religion. Grace, as we have discovered had been a society girl and Hugh, a well respected country doctor. They did not come to the wedding. We can only imagine the conversations, the arguments, the pleading. To them, Jim’s parents, their precious son was denying himself an afterlife in Heaven, and bringing shame on the family. Any children born to this marriage would be viewed as illegitimate. In the eyes of the Catholic Church our parents were not married.

One “family story” tells of Jim’s sister, Tish, writing a letter pleading for them to “marry properly”. As children we knew that our father had “left the Catholic Church” in order to marry our mother and that he had been “cut out of the will”. It is part of our family mythology. We were aware of our mother’s bitterness at our family’s financial struggles. We witnessed the stiff courtesy with which she greeted her mother-in-law, who she always addressed as Mrs Bourke.

Now, looking at the stark reality of this newspaper article, we feel a little of her outrage. We understand better the enormity of that decision, the extraordinary timing of Hugh’s change of will, the sense of being the ‘black sheep” family that hung over us when we visited out Grandmother.

blog comments powered by Disqus