July 2016

Twenty-Eight Moore Street

13 07 16 15:47 Filed in: Children 1950s

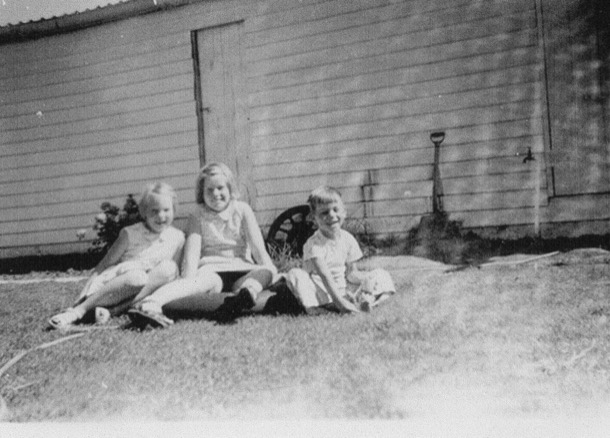

Alice describes the acquisition of the land in Box Hill South in 1946:

Dad built the house over the following six years, while studying night school and working full time at the gasworks in Box Hill. Sue remembers going to the Moore Street site, Dad walking and she riding her trike. On one memorable occasion, on the corner of Broughton Road and Elgar Road she remembers waiting while a circus went past: wild animals in cages and horse drawn vehicles.

Neither Sue nor I remember the move from Boronia St, but it must have been in 1952. The house was never actually finished. The back door remained the one Dad had knocked up to lock up the house. We four kids all lived there until we were in our late teens or early twenties and our mother remained living in in the Moore St house until she was in her fifties.

The house is still there. It had a view over Mt Dandenong, and was pretty much on the edge of suburban development. Beyond, further east were orchards, unmade roads and “the country”.

Outside was a garden, overlooked by a grass terrace, which had French windows opening onto it. Later this terrace area became a “rumpus room” when our grandparents built a flat onto the back of the house in about 1960.

Right down the back was a vegetable garden and chook pen. Sue remembers hanging on the fence eating an apple, and looking into the paddock next door.

The driveway led through full height double wooden doors into the garage. I remember the garage full of shelves of smelly, dark looking tools, piles of sawn timber and car bits. Our first car was a Talbot, huge and square. it was cream with red leather

Later it was replaced with a Sunbeam. I remember being confused about the Sunday School song “Jesus wants me for a sunbeam”, but lots about life made little sense. This was just one other enigma.

Attached to the side of the garage was a garden tap, and at the end, a swing.

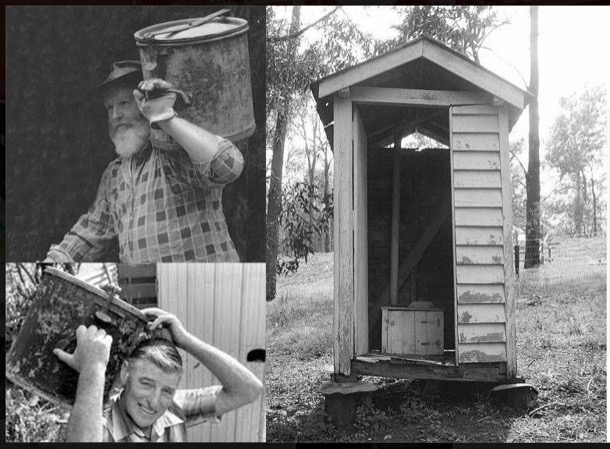

Part of the garage building was the alcove for the outside toilet, which we used until the sewerage came through. The toilet consisted of a can with a shelf above it, with the seat built into the shelf. At night we used the potty instead. Our bedtime instructions were “potty, teeth and bed”. The "can" was collected every week by the "dunny man".

Moore Street House Room by Room

The Girls’ Bedroom.

Sue and I shared the front room of the house. Initially, the room was a pale dusky pink coupled with a pastel greeny aqua. Later this was changed soft grey with navy and red curtains, replacing the white venetian blinds, and navy blue bedspreads. Sue remembers buying the fabric for the curtains and bedspreads, with Auntie Marge as style consultant, from a shop in Richmond.

Dad built double bunks, offset, with drawers under the upper one, and a plywood dressing table opposite the bunks and long desk under the front window. Sue remembers working on that desk as an older student.

We wore cotton nighties all year through. Sue slept in the lower bunk, and I the upper one. Above my bed was a high window. I remember standing on my bed watching an occasional visitor walking down the driveway below. On cracker nights, after all the neighbourhood kids were back home in bed, the window also afforded a view of Gilbert Soames, the older, strange boy next door, letting off his own crackers, all by himself, in front of his house.

We went to bed at the same time, in spite of the three year age gap. We would read until lights out, (and sometimes afterwards with clandestine torches or a candle). We also talked in the dark. A favourite game after lights out was to take it in turns to relate “everything I did today from waking up until now”. This would often mean a droning voice going on long after the other one had dropped off to sleep.

In Spring the pittosporum in front of the room filled the air with its sweet blossom.

Around dawn there would be the sound of the milkman’s horse clip clopping along the street.

During one of the evenings leading up to Christmas a small brass band from the Salvos might stand on the street corner and play carols, before marching off to the next street. On Christmas morning there would be a satisfying lump of filled pillowslip on the end of each bed.

Clothes storage was in a singe wardrobe, the drawers under the upper bunk, and shelves in another cupboard.

We had very few toys, a few dolls and books mostly. These lived on two, usually messy shelves in the cupboard. There was always a pile of cartridge paper for drawings, on one side of which was Dad’s students’ mechanical drawing school work. We don’t remember playing in our bedroom, in fact really only reading, lying on our beds.

The sheets were changed once a week. The top sheet would be put on the the bottom, (there were no fitted sheets) and the bottom sheet and pillow slip would be changed.

An overwhelming memory is of hot nights. The room faced west and there was no insulation, let alone air conditioning! Sometimes Mum would bring us each a wet face washer to put on our forehead, but it soon became warm again.

Getting up after we had been put to bed was frowned on. Sue remembers the dark hall that led from their bedroom as terrifying. It was a big deal to get up. I remember worrying a loose tooth until it came out, as this was a big enough excuse to tiptoe up the hall and open the door into the living area, where our parents sat and read and smoked cigarettes after the children were in bed. There were no night lights, except a friendly street light nearby. It was often frightening at night. One summer’s night, after a trip to the beach, I remember being quite certain I could hear “a man” lighting matches nearby, trying to burn the house down. The next morning, it was discovered that a bowl full of crabs in the boys room, brought home from the beach, had escaped and spread all over the house, scratching their way through cupboards and creating scary noises.

The Boys' Bedroom

Yeah, well it was a boys' bedroom.

The Bathroom

One bathroom served the family of six. The floor was black rubber, and a home made stool was covered in the same rubber.

The large pink bath had a towel rail attached to the wall above, right along its length. When more than one child was in the bath, these “fell” into the water often enough for “Mum, a towel fell in the bath!” to seem a familiar call. A shelf at the end of the bath held face washers, a few alarming medical devices and a tin of borax, for athletes foot. Sometimes there would be a bath toy such as a pop pop boat, but these were rare.

The shower recess, protected by its curtain seemed dark and a bit scary. There were no tiles, just cement sheeting, and it seemed a bit icky and threatening.

A little cupboard above the pink basin held Dad’s shaving things, the tooth brushes and toothpaste, a compact and a few very red lipsticks, which had worn into a concave pattern. Nail scissors were attached to a pink metal stand, picturing glamorous lady pictured bending over slim legs, said ”Now cut those toe nails!” There were a few rudimentary first aid items and a deodorant which was a cream in a shallow bowl with a glass lid. There were also bars of yellow velvet soap, which these days we would call laundry soap, and which were used for everything: hair, bodies, dishes, hand washing of clothes and floors. There was no vanity table. The basin stood on a pedestal, with hot water pipes covered in hessian lagging.

A long narrow room off the bathroom was built ready for when the sewerage was put on. In our early memories it holds building detritus. Later it had a toilet in it, but there was never a door.

The Parents’ Bedroom

The wooden double bed was made by Dad. Mum’s side had a bedside chest of drawers on which were books, a Bible, and a lamp. Dad’s side had a chair on which he kept similar items.

There were three built in wardrobes. One each for hanging clothes, and a middle one with shelves either side. Dad’s side smelt of leather and tobacco, and held his collection of 78 vinyl records, and his pipes. Mum’s smelt of perfume and had a very few items of jewellery and lacy underwear . The top shelf on Mum’s side was the hiding place for Christmas and birthday presents.

The Hall

A square entrance hall in our early memories is empty, except for the cupboard in which we hung our coats.

Later when we had a telephone (our number began with XY) there was a black metal monstrosity called a “telephone table” with a wooden seat and a shelf for the telephone and the jar, into which we had to put money when we used the telephone.

The Kitchen

The kitchen table at Moore St was the centre of the house and its large plywood surface saw many varied activities besides breakfast, lunch and dinner. It hosted our mother reading The Age from cover to cover and then playing Patience; (instead of doing more mundane tasks like housework) sewing all manner of things from trailer covers, curtains and summer clothes; lots of talking and even a seance or two in later years.

The walls were bright yellow and the ceiling pale blue. Large cupboards and a gas stove and oven occupied one wall and adjacent to this was a long row of cupboards topped by crowded benches and a sink where we fought over who should wash and who should wipe the bench after the job was done. (The rules were complicated! NOT, just the interpretation.)

The oven was another focal point. On top was a metal ashtray holding a few coins and used matches, a hairbrush and lots of letters and bits of paper. Margaret and I both had our hair done in front of the oven in the morning, marking our growth by the marks on the oven door.

Beside the stove was a salt cellar and an old jam tin into which the dripping was poured.

The only appliances were a Sunbeam Mixmaster and the electric frypan kept on the bench near the stove. With the pile of newspapers under the corner cupboard, the sink and our two appliances there was only a small preparation space for the busy work of school lunches and daily cooking.

Sue remembers the ice chest in which was stored a large block of ice delivered by the iceman who with a hessian bag draped over his shoulder, carried in the big block ice held in place with a large ice hook.

A grey wooden fence was about two and a half metres away, outside the kitchen window. A double row of hand laid red bricks made the driveway, with a narrow garden bed each side. Under the window were red geraniums and blue campanula climbed the fence. The Soames' garden next door had fragrant mock orange and honeysuckles trees, whose perfume would waft in on the breeze. Most nights, from a very early age, Sue and I stood at that window and washed and dried the dishes.

The Laundry.

This room seemed small, dark, crowded and vaguely threatening. It was very much a utilitarian room, made of unpainted fibre cement sheeting. There were often metal buckets of mysterious items soaking in the concrete troughs, under which was an enormous pile of newspapers: The Age which would get soaked through when one of the troughs overflowed. Above the troughs a shelf held Rinso washing powder and the iron. Early on we had a small washing machine topped by a mangel. It wasn’t until the mid nineteen-sixties that we had a modern spin drying washing machine. On the other wall of the laundry was a huge hot water tank on a stand and the briquette hot water service, on a lower shelf under which was the hessian bag of briquettes. There was a tray of apricot coloured ash to be emptied under the fire box. Behind the door, brooms and mops were kept along with the ironing board and an electric floor polisher. There was often a clothes horse of clothes and nappies, drying by the hot water service. No wonder it seemed crowded.

The Dining Room

Grandma Bourke gave us the large shiny wooden dining table and chairs. We don’t know the circumstances of this gift. Maybe it became redundant after Grandpa Bourke died in 1950, and she moved out of the large house. We ate our evening meals around this table, complete with instructions about table manners and the endless wars about eating all one’s vegetables. A barely used open fire was on one side of the room and a huge gothic sideboard on the other. Wedding presents, seldom used platters and bowls and precious cups and saucer sets were kept in the lockable cupboards, and a few on display in the glass fronted middle cupboard. There were also drawers. We remember the items that lived in this sideboard with hushed reverence. There was a set of fish knives, cake plates and cake forks, wine glasses, smoked glass dessert bowls, serviette rings, doilies and other embroidered items, “ornaments” including a china “old fashioned” lady with a blue skirt made of hardened net.

The Lounge Room

On one side, French windows opened out onto a grassed terrace. On the other, venetian-blind covered windows on two walls met in the corner of the room. There was an open fireplace, which later became a “Wonderheat”, gas heater, and a stone hearth. The early furniture in there were huge dark chairs, a cream rocker and a gramophone with its red fabric covered speaker and curly legs. An ashtray on a stand, with a box of matches perched on the side, sat beside the fireplace.

Later, in the nineteen sixties the room received a makeover and black tubular furniture with and a pair of Fleur armchairs with grey and aqua vinyl cushions took over. The television, hired initially around nineteen sixty, for a summer Ashes cricket series and watched on the dining room table from the kitchen, eventually became the focus of the lounge room. There were only five chairs. The boys sat on the floor, often engaged in vigorous play fighting, especially when World Championship Wrestling was on.

The Necessities of Life

In so many ways, as you will have realised, we grew up in a very different world. Many of the items we now automatically drive to buy in the supermarket, were delivered. The following is a very descriptive account of the daily deliveries and the weekly rubbish collection. By the way, there was one rubbish bin per household, and all rubbish was wrapped in newspaper. Wrapping the rubbish so that the contents were secure, was quite an art, as you can imagine.

“The driver moved forward about three houses at a time and the garbos ran down the street knocking the lids off the old-style galvanised iron bins. Then they hoisted the bin to their shoulders, ran back to the truck, tipped the load over the side (there were no compactors in those days), giving it a good bang on the edge to make sure all the contents were dislodged. Then they chucked the bin onto the grass verge.

It has occurred to me since that the advent of grass verges, ‘nature strips’ as they were improbably titled in the new suburbs then springing up, may have been partly to help muffle this noisy process. With all that running and hoisting, garbos had to be very fit and, unsurprisingly, many were football players. They also collected empty beer bottles (to be refilled), which they stowed in big hessian bags slung on the rear of the truck.

At Christmas it was the custom to leave the garbos a bottle of beer or three for their Christmas party. If you didn’t leave them a drink, they spilled some of your garbage on the nature strip.

Virtually every household had milk and bread home delivered. In the mid-1950s there were still a hell of a lot of people who didn’t own a car, so there was a lot of demand for these services. There were no supermarkets providing the whole range of daily necessities, and even the electric refrigerator wasn’t yet a universal feature of homes. I can remember my parents, when I was very young, relied on an old ice chest, for which a block of ice measuring about 30 centimetres square was delivered every couple of days by the iceman.

Both the milkman and the baker used horse-drawn vans. In an age when motor vehicle ownership was surging ahead, this was still a more efficient way to make deliveries than using a motor van, because there was no need to jump into and out of the driver’s seat all the time. The baker or the milko whistled to signal the horse to move on down the street. Once the horse knew the round, the deliverer didn’t even have to do that. It just ambled on to the next regular customer and waited obediently outside.

The baker trotted down the street carrying loaves in a big wicker basket slung on his arm. There were only two types of bread: ‘white’ and ‘brown’ (or what we’d call wholemeal these days). They were high-top loaves which could be broken into two halves. Some people only had half a loaf delivered each day and maybe a full one on Fridays for the weekend.”

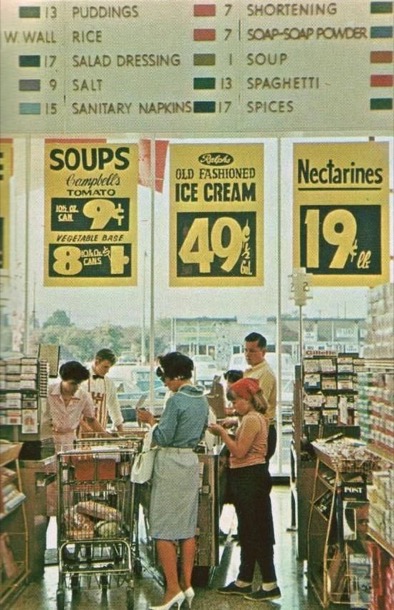

Our mother walked to the local grocer, fruit shop and butcher once a week where the rest of the food was bought. The shopping was delivered to our house until we bought a car. From then on the shopping was collected by our father on his way home. The butcher and greengrocer were much the same as today, except that the butcher had sawdust on the floor and there was not a piece of cling wrap plastic to be seen. The grocer however was very different.

No taking pre-packaged items off the shelves. Instead, the grocer served his customers, putting all the items bought into very sustainable brown paper bags. Big tins lined some of the shelves that held such items as biscuits, broken biscuits and small items such as dried fruit. Larger bins held flour, sugar etc. The best thing about the grocer was the inexpensive treat of a small bag of broken biscuits. Soon after we moved to Box Hill South, the amazing Foodland Supermarket opened and gone were the days of personal service and bags of broken biscuits for children.

Comments