Hair

This post therefore is about hairstyles, but we have allowed ourselves a much broader scope.

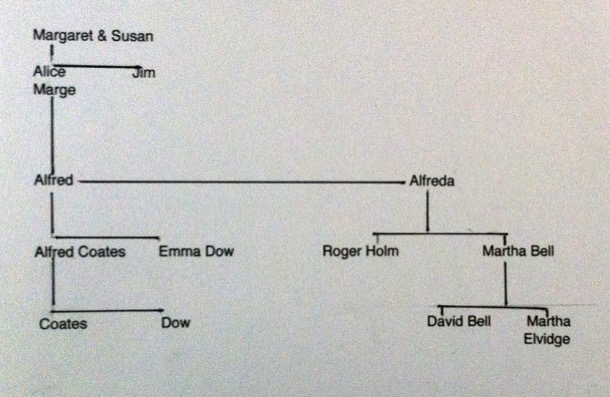

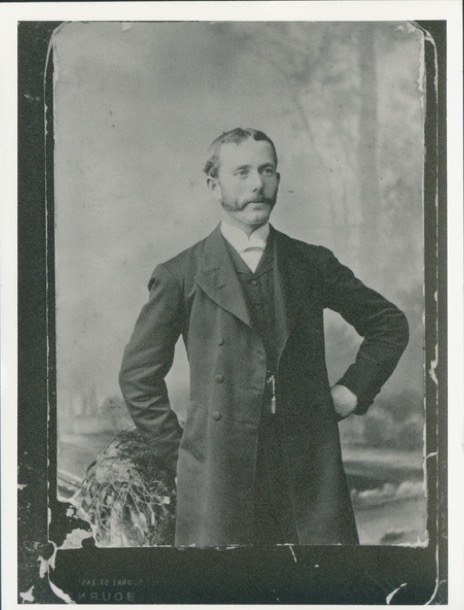

ALFRED JOHN COATES

Alfred John Coates, born in 1857, was probably in his late twenties when this photo was taken. He was our maternal great grandfather and was a Methodist Pastor for most of his working life. In this photograph Alfred is a young man in prime of life, dressed in formal dress and sporting the fashion of the day: mutton chop whiskers, carefully manicured to join artfully with the moustache. A man of destiny, the misty ‘bush’ behind him, he stands erect, eyes on the future. At this time Alfred was apparently a boiler maker in Ballarat.

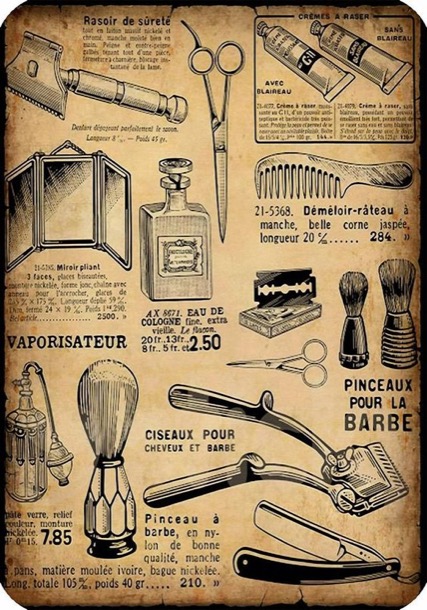

Men’s facial hair trends were changing rapidly in the late 1800s. Long beards were out and clean chins and cheeks and a well-manicured moustache were in. To achieve this look men would need to go to a barber two to three times a week or shave themselves.

Shaving oneself may have been a financial necessity at times but it could also be a dangerous procedure. Shaving was done with a straight steel razor that required care and expertise, not only in the act of shaving the gentleman, but also in the care of the blade. To keep it sharp, the blade was rubbed against a leather or canvas strap before each new shave. As well as the blade, shaving soap, shaving brushes, combs, oils and wax were essential items to achieve the desired effect.

Having a photograph taken in a studio was a special occasion and a relatively expensive exercise. One can imagine that Alfred may have had a trip to the barber to ensure that he looked his best.

Safety steel razor blades that made shaving much easier were not invented until 1895 by an American business man with French heritage.

King C. Gillette invented a low cost blade that was easily replaceable and gave men safety and the freedom to achieve the look desired themselves.

EMMA ELIZABETH DAU

Alfred married Emma Elizabeth Dau in 1888. He was thirty-two and she was twenty Maybe this photo was taken at this time:

Emma is dressed in the style of the day, hourglass figure no doubt with a corseted waist as she gazes into her future with a determined tilt of her chin. Her hair is tightly curled at the front and pulled back into either a bun or pinned up plait.

Unlike the men who had barbers to attend to their needs, there don’t appear to be many ladies' hairdressers. Women had many home implements and potions and maybe sisters and mothers helped each other with their hair.

Young Emma’s tight curls may have been created with curling irons. A curling iron consisted of a metal rod that was held over a flame or burning alcohol to heat it, before wrapping the hair around it. Hey presto, curls!

Later in life, Emma wore her hair in a more relaxed style, loosely pulled back from her face and pinned up into a bun at the back:

When this photo was taken, the height of fashion for women was to wear their hair with more volume at the sides. This was created by using clumps of hair leftover in combs and brushes, to pad out the sides. Emma would not have gone to these lengths in later life, but on her dressing table she would have had a brush, comb, hand mirror and china box, with a lid for the collection of hair caught in brushes or combs. We can remember our grandmother, Alfreda, also having these items on her dressing table. She wore her hair long all her life. During the day it was loosely tied back in a bun, brushed out at night, and the ‘ratts’ collected from the brush and placed in the china box. She then plaited her hair into a loose, single long plait and was ready for bed.

NINE DAU SISTERS

Emma Coates, was born Emma Dau. She was one of seventeen. The first nine of these were girls.

We have three amazing little photos of some of the Dau children. We have spent a long time staring at these images, noticing little details, wondering about the lives of these nine little girls.

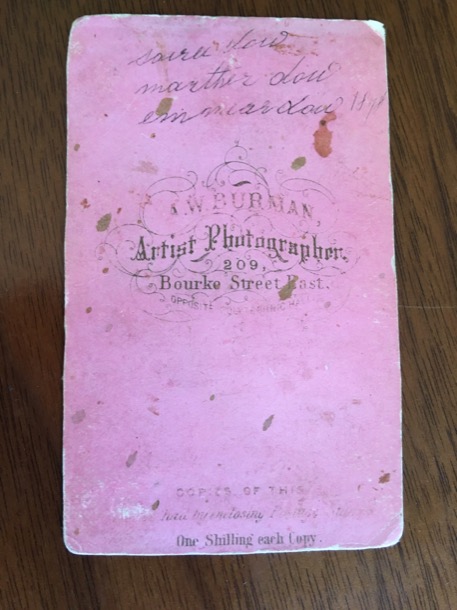

The first question we had was, "Were the three photos taken at the same time?". There is such a family resemblance, we weren’t sure at first whether they were different people in the three photos. The carpet gives away that they were taken in the same studio. On the back of one of the playing card sized photos, we see “one shilling per copy”. For context, at that time, a shilling was more than a day’s wage for a working man.

It seems most likely that the three photos were taken on the same day, and they are the nine oldest children, all daughters, of Joachim and Martha Dau, our great, great grandparents.

The photo of the three eldest has writing on the back:

The fact that Martha is misspelt as “marther”, and that no capital letters are used, might be a clue. It was not our mother Alice, nor her parents. None of them would have made such a basic spelling error! The surname is listed as “Dow”.

If those names are correct, then these are the three eldest Dau children. Standing is Sarah, the eldest. the other two are Martha, known as Mishi, and Emma, our great grandmother.

Thanks to the Wandong Historical group, we have the details of nearly all the Dau children.

The next three girls are Bella, Jane and Sophia, followed by Alice, and two others, possibly Annie and Nance, although some sources have Annie and Nance as the same person.

There is no date on these photos, but there are nine girls. The nine first Dau children, all girls were born between 1866 and about 1878. This puts the date of the photos at about 1880, with Sarah, the eldest, aged 14 and the youngest aged 2.

The girls’ father, Joachim, had spelt his surname, Dau. We don’t know the exact date they changed it to Dow, but Frederick enlisted to fight in the Boer War as Dow in 1901, and Arthur, who became a professional soldier, changed his name by deed poll to Dow. The same anti German sentiment that caused the British Royals to change their surname to Windsor from Saax Coburg was no doubt responsible. And yet the Dau spelling persists alongside the Dow spelling, right up until 1929, when Sarah, the eldest wrote about her childhood. Our mother and aunt did not even know about the Dau spelling.

The photographer is listed on the back as Burman, 209 Bourke St Melbourne. The building is still there. This is what it looks like today:

There are a number of old photos by Burman available on line, with that tell-tale carpet visible in some. This one, “Portrait of a Lady”, which uses the same chair as two of our photos, is from C1865.

We picture the little farm girls, in their new dresses, in the big noisy city. They would have come on the train, to Flinders Street from Wallan, and walked the three city blocks to the studio.

The city streets would have looked like this:

Their hair would had been in rags overnight. The curls in Sarah, Martha and Emma’s hair have been successful; the others less so. All of them have a ribbon holding their hair back from their face.

The dresses are interesting. The same fabric and pattern seems to have been used for the three eldest girls. Who made them? The next three also have a similar style. All have sturdy boots and frilly pantaloons. These outfits would have been worn to church on Sundays. Did they wear them for the train journey, or change at the studio?

The only other girl, born in 1887, preceded and followed by the seven boys, was Ethel. She wrote diary entries, still held by the Wandong Historical group. Ethel wrote about the boots, which are such a feature of these little girls’ photos. “the rough track across the paddocks and hills, two miles to the little school at Wandong. In wintertime, we had to cross many flooded gullies. We wore strong boots and I was often peeved, as I compared my strong shoes with the dainty ones worn by the other girls at school.”

It was quite an expense to provide boots for so many children.

Our appetite for finding out more about this family is well and truly whetted. We plan further exploration, including an excursion to Wandong.

THREE HOLM SISTERS

These three young women, probably photographed just before the first world war are (left to right) Alfreda, Beatrice and Berta Holm. Alfreda, our maternal grandmother, was the oldest of the three, perhaps just twenty at the time. The three sisters have their long hair swept back in gentle waves, to a loose bun or twist at the back.

We wonder whether they did the white work on their shirts? We know that Beatrice and Berta spent time working in Finders Lane, doing the white embroidery known at the time as “white work”. So much we can only guess at.

They all gaze into the distance: Alfreda with a determined steely gaze, Beat with a quizzical half smile and Bert’s beautiful eyes not quite hiding her vulnerability. We can only guess, as they gaze into a future where world war is imminent.

Alfreda wore her hair long all her life. We can remember her brushing her hair at night and putting it into a long plait.

TWO COATES SISTERS

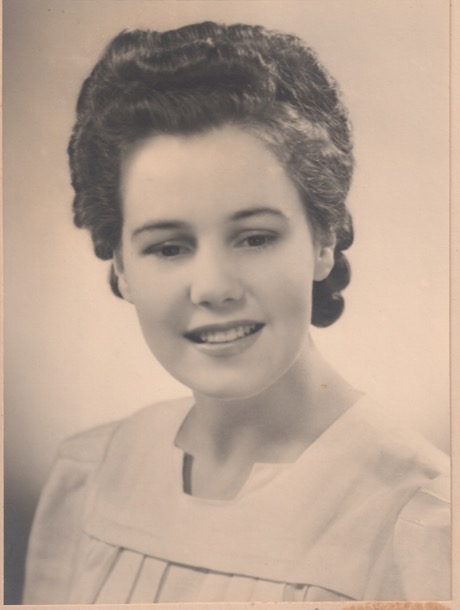

It’s hard to be a younger sister, but our mother Alice, was the fairly plain younger sister of an extraordinary beauty.

She didn’t have to deal with social media, but, when she was growing up in the 1930s, feminine beauty was important for girls.

Alice was an intelligent and able scholar, and, thank goodness, this was highly valued in her family. Her mother, Alfreda, had made sacrifices and fought for her own education. For their later secondary school, the girls were sent, at huge expense, to a city based secondary school, all the way from Croydon.

Only the wealthiest or most determined families sent their girls to school, after the age of fourteen. At McRobinson Girls’ High School, Marge and Alice were taught by, and shared classes with, the very brightest and best: future women scientists, lawyers and doctors, who would pave the way for our own generation.

But, from her school reports, we see that, while she held her own on the whole, Alice was not exceptional in that auspicious company. And she was crippled, probably her whole life, by a sense of inferiority.

And it is in their respective hair cuts from that time, that we see how the contrast between the two girls was accentuated.

When I stare at those grainy old photos, at Marge’s lush locks, and Alice’s blunt, unfashionable short bob, and straight fringe, I cannot help but ask “Why?”. Why did Alfreda allow her younger daughter to wear such an unflattering style. Why was the difference in feminine beauty accentuated and underlined so prominently by the two hairstyles? How might Alice’s life have been different, had she been encouraged to make the most of her looks, as well as her brains?

Even as they began working life, both at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory, in 1939, the difference remained. Here Marge is on the far right, and Alice on the far left. Alice is nineteen and Marge twenty-one. But the choice of hairstyle reflects very different attitudes about their appearance:

THE VICTORY ROLL

These two studio photographs of Marge are portraits of a beautiful young woman, but what does the hair tell us?

Here, a younger Marge still has very long hair, worn up now, as befitted a young woman who was no longer a child. Pretty curls and barrel curls were the look, and Marge had beautiful, wavy, very cooperative hair and was able to construct ‘the look’ very successfully.

An older Marge, maybe just twenty, posed for this studio photograph as a young woman of the war years, in the “hottest” style of the time. This photograph shows a confident young woman with a job, and presumably many admirers.

During the war, particularly during the Battle of Britain, the ‘Victory Roll’ evolved as a very popular and flattering hairstyle. The style was based on an aerobatic manoeuvre performed by pilots to signify victory. The planes would spin horizontally in celebration. The ‘Victory Roll’ hairstyle would have been difficult to execute, so hours of practice and experimentation was required. The style has stood the test of time, as it is still popular today in ‘retro’ dressing. There are many YouTube videos available with full and detailed instructions.

‘THE SET ‘

After the second world war, women’s hair fashion was dominated by ‘the set’, often a weekly set. Some women did their own at home, but others, such as our mother Alice, went to their local hairdresser.

The set involved a headful of rollers, tightly wound on wet hair, then dried under a hood dryer. This often took almost an hour, so there was time to read or chat.

Through the ages, and the generations of our family, both sexes’ hair styles have been influenced by the fashion of the day. We have all had cuts, or not. We have curled and permed and coloured and bleached, with varied results.

Today, people are not rigidly restricted to one style, as they were in the past, but have any options.

The lyrics from the musical Hair says it all: .

‘Gimme a head with hair

Long beautiful hair

Shining, gleaming,

Streaming, flaxen, waxen’

The Demon Drink

It was clearly uncommon for anyone in our narrow anglo world to drink at home. Here, for instance, is an extract from a Primary school resource book on Temperance from the 1950s.

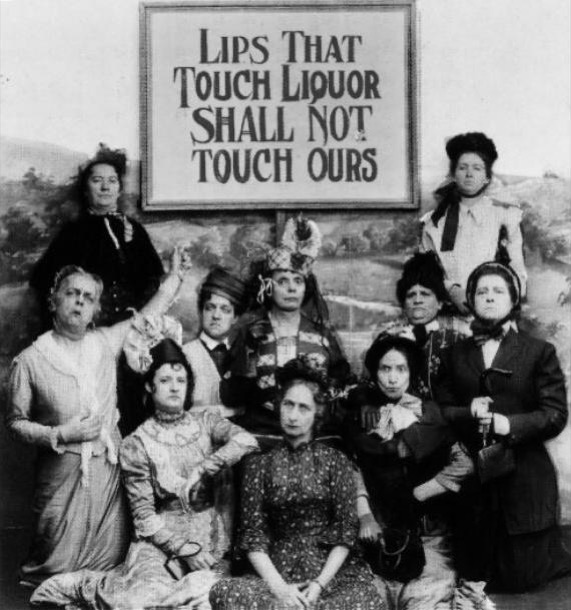

The international Temperance movement was one of the most powerful social movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Its advocates regarded alcohol as a social evil and sought to have it banned entirely, or at least its consumption drastically reduced.

Initially it was just a move against drinking spirits and “hard liquor". But during Victorian times it became more a push for total abstinence and became more specifically a women’s movement, connected with Protestant Christianity. Groups of women activists were to be found right across the western world.

The Temperance movement had its most obvious success in America, where the sale of alcohol became illegal across the whole country overnight in 1920.

This period of American history has become known as ‘Prohibition”, the Roaring Twenties. It conjures up images of gangsters, speak easies and moonshine. The law did not have the support of much of the population. But it wasn’t until 1933 that it was finally repealed.

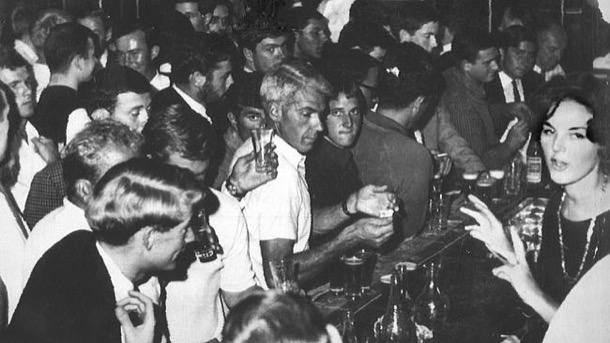

In Australia the temperance movement did not succeed in having the ‘demon drink’ banned but it did lobby vigorously for restriction of hotel opening hours. By 1923, hotel opening hours were restricted in all states. The closing of hotels at 6.00 PM led to a phenomenon known as the ‘Six O’clock Swill’.

It is hard to believe looking back that the daily rush to the bar was part of everyday life. Rather than limit drunkenness it actually encouraged it, as men who ‘knocked off’ work at 5 o’clock had only on hour in which to drink. Hotels were set up to serve as many beers as were demanded in this hour. Pubs were overcrowded, as men five or six deep lined the bar waiting to be served and patrons spilled out into the streets.

Pubs did smell strongly of beer as so much was served in such a short time. Sue can remember walking past Young and Jacksons on her way home and pushing her way through the throng of men, spilling out onto the pavement on the corner of Flinders Street and Swanston Street. Men, yes only men! Women were not permitted in the Bar until the early 1960s and for many years after that it was frowned upon. We can remember conversation stopping momentarily when we first walked into a bar, particularly in the country.

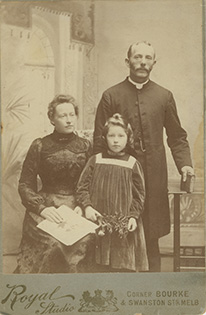

The Demon Drink indeed! We come from a long line of teetotallers: our great grandfather Reverent Alfred Coates, our great aunt Sister Bessie, our maternal grandparents, Alfred and Alfreda, their siblings and our parents. Our mother’s family, the Coates, being staunchly Methodist, we imagine would have been very sympathetic to the temperance agenda. Here is Alfred, in his Methodist pastor uniform with Emma and their daughter:

We were very aware as children that none of our family touched alcohol and that it was particularly frowned on by our rather upright Grandfather.

We too, at the tender age of eleven of twelve, have had our brush with The Independent Order of Rechabites, who provide educational material for Victorian Schools.

Alice and Marge as old ladies recounted their childhood memories of drunkenness, in the country town of Croydon during the 1930s, with obvious disapproval and distaste. Here they discuss the public drunkenness they witnessed at the hotel and wine hall near their house:

I remember our aunt having a glass of beer at the dinner table, when we were staying there as children. I commented on it and I remember being rebuked. Later our mother told me that it was medicinal, that she had found that drinking beer with food helped her digestion. That mum had felt the need to explain it that way, and that our aunt had reacted so strongly to a child’s interest is understandable in the light of heir own childhood experiences and family attitudes.

And then, during our late teens, as the 1960s became the 1970s, this part of our past just melted away. It became normal and natural too open a bottle of wine to share. There was binge drinking around us, especially at Uni parties, and the drink driving hazard was evident, but the moral dimension, the “holier than thou” attitudes, the raised eyebrow were all gone. Society had grown up about the same time that we did.

.

Alf and Alfreda: the Early Years

Alfreda, our maternal grandmother was living in St Kilda and attending the Melbourne Continuation School in the early 1900s. While she was finishing her secondary education. Alfreda met her future husband Alf, who was recovering from rheumatic fever and had left his country teaching position and moved to Melbourne to work at Blocky Stone, a hardware supply company. Alf boarded In St Kilda with his aunt Mishy Cowden. Arthur, Alf’s older brother had also boarded there and Arthur had an attractive young girlfriend, Alfreda Holm; not for long! Alfreda must have been quite attracted to this tall red headed young gentleman from the country. She abandoned Arthur, and Alf and Alfreda became ‘sweet hearts’ when she was 16 and he 17.

Alfreda completed the secondary schooling she had so desired. Even though she could have sat for the University entrance exam, her family could not support a full time student. Teaching was her only option. At the age of 18, she embarked on her teaching career at Elsternwick Primary School.

Elsternwick Primary School

Alfreda’s and Alf’s courtship was, as was the custom, a very proper affair and one would imagine that this was so, as Alf was the son of a pastor. Outings included picnics on the St Kilda Foreshore:

and ‘doing the block ‘ at the Block Arcade in Collins Street:

Collins Street

Alfreda pictured in 1910.

As Alf played cricket most Saturdays during the cricket season, Alfreda would have accompanied him; in fact she became so involved that she was appointed scorer.

Outings further afield involved visits to Alf’s family at Diamond Creek where Alf’s father was the Pastor at the Methodist Church. In the early 1900’s this was really the country and Alfreda enjoyed these visits and her introduction to country life.

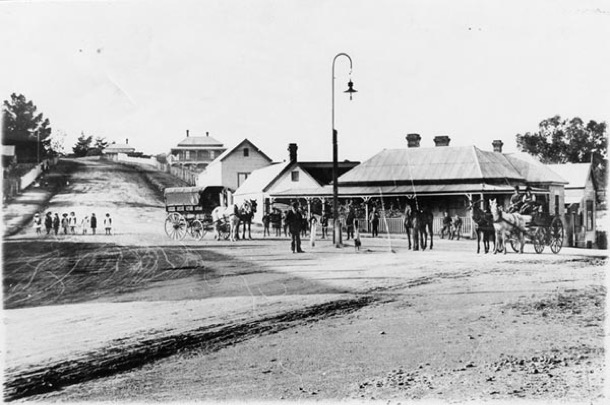

Diamond Creek around 1910

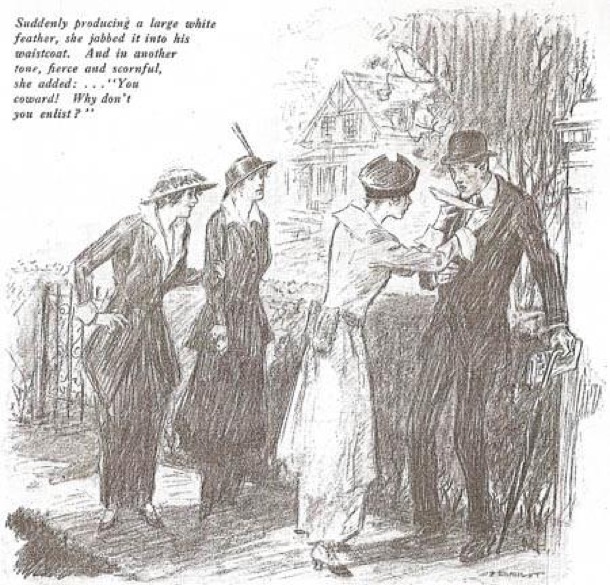

War in Europe broke out in 1914. Droves of young Australian men were enlisting in the army, hoping that it would last long enough for them to get there and have the great adventure it promised to be. A wave of fervent nationalism swept the country. Alf had recovered from the rheumatic fever that had ended his teaching career, but the residual heart damage meant that he was rejected for military service. A young man not in uniform, he was given a “white feather” as a mark of cowardice.

He suffered what was called a “nervous breakdown" which, at the time, was attributed to embarrassment and shame.

During his recovery, he lived in the small town of Eildon Weir, 140 kilometres away, where he managed the general store, selling supplies to the men building the weir.

Alfreda remained loyal to Alf first through his illness, which today we would call clinical depression, and then through his extended absence at Eildon Weir.

Later in 1914 Alfreda’s family moved to Surrey Hills, and Alf moved with them. Alfreda got a job teaching at Balwyn Primary School and Alf went back to his city job. They lived at Elwood Street Surrey Hills. Alf told the story of walking with a lantern down Florence Road in the early morning to catch the train at Surrey Hills station.

Alf and Alfreda were married on December 27th, 1916, at the Surrey Hills Methodist Church, which is still there today:

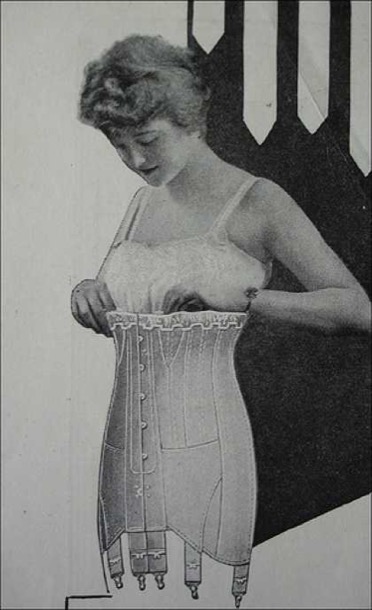

Alfreda did not dress as a bride. Marge tells us in the tapes that this was because it was war time, but a quick search shows plenty of women in full bridal regalia from that time. Perhaps they were super sensitive to how it would look, given that Alf was not “in uniform”. In any case, she wore a cream silk suit. She may well have had it made in the new fashion of flared skirts:

And underneath she would have worn a body moulding corset. Bras, which supported rather than moulded, were in their infancy at this time. They were patented in 1914.

The couple honeymooned at Ocean Grove. There was a steam train all the way to Queenscliff at the most southerly part of the Bellarine Peninsular. And then there would have been a bus to Ocean Grove and finally a ferry across the river.

Until 1927, the only way to cross the river to Ocean Grove was by ferry and local ferryman Mr Abenathy would row you across for six pence.

Alf and Alfreda set up home back at Eildon Weir, where Alf resumed his job managing the store.

Out the front of the Eildon Weir store. Alf in a suit at the extreme left.

Alfreda had become pregnant very quickly, and the first few months of their married life had been hectic. But the still birth of the baby at seven months was attributed to a fall. It was flood time at Eildon Weir, and no doctor could get to her. A local midwife helped her through the difficulties of labour with a dead baby. She lost a lot of blood and struggled for twenty-four hours in the final stages of labour. Afterwards, she was not allowed to walk for six weeks.

Alf buried the dead child in the back yard of their little house. It was a boy, who was to have been named Peter. Interestingly it wasn’t until 1930 that “viable” still born babies had to be even reported to the authorities, and even later before they were registered. Nowadays a doctors certificate accompanies a detailed registration document, which must be lodged within forty-eight hours.

Within a couple of years the weir building project was finished, the workers dispersed and the now deserted town was swallowed up by the new Lake Eildon.

Eildon today.

Alf and Alfreda moved back to Deepdene, an eastern suburb, and Alf returned to his city job at Blocky Stone.

Great Great Grandparents

Like many Australian families, ours is a story of migration to a new country. All four of our maternal great great grandparents were European: English, German, Danish and Irish.

These four migration stories happened between the 1850s and 1870s. Three of the migrants were our great great grandparents, and one was a great grandparent.

COATES, ARRIVED VICTORIA 1860s

Coates was an English engineer who travelled with his wife to Australia in the 1860s. Their first names are not known.

The Barwon River is the large river than flows through Geelong. In the new colony, there were no iron works: the worked iron had to be imported from England, along with the experts to do the work.

Barwon Bridge then

Barwon Bridge now

We don’t know whether Mr and Mrs Coates planned to do this job and then return to England, but they would have found a thriving, wealthy colony. Gold had been discovered in central Victoria just ten years earlier.

DAU, ARRIVED VICTORIA 1860s

Dau was a German farmer who arrived in Australia in the 1860s. He married a fifteen year old girl, of whom we know very little. Wandong is 70 Kilometres north of Melbourne. In the years the Daus lived there, there was a thriving timber industry and some gold mining. By 1880 there was a railway line from Melbourne.

HOLM, ARRIVED ADELAIDE 1872

Roger Holm: this one is our great grandparent, a baker, who himself arrived in Australia from Denmark via England in 1872.

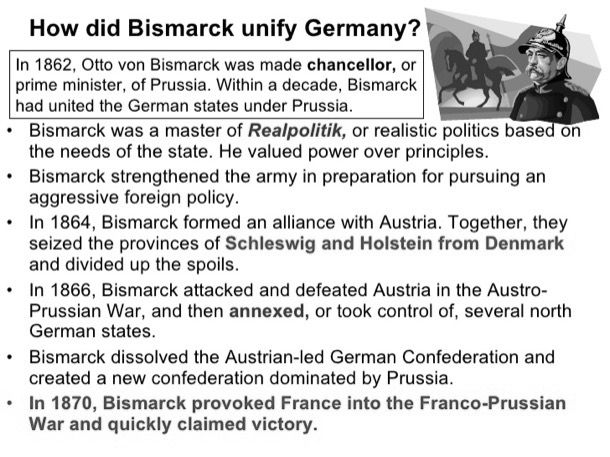

Roger had been born in a part of Denmark called Schleswig-Holstein, that had been disputed territory for centuries. At the time when he was a child, Germany did not yet exist. It was still a whole lot of little countries. When Roger was twelve, Otto Von Bismarck’s army invaded Schleswig-Holstein.

Map of Schleswig-Holstein

Otto Von Bismarck

Painting: Bismarck Wresting Schleswig Holstein From The Danes

BELL, ARRIVED VICTORIA 1850s

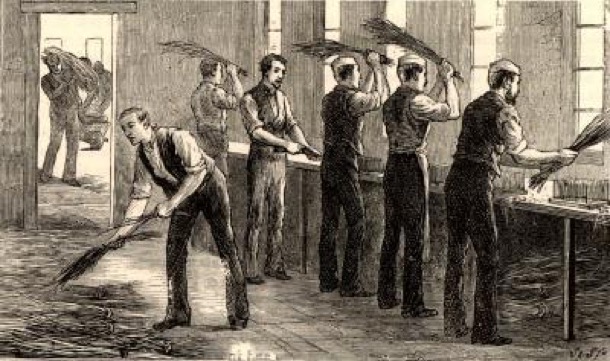

David and Martha Bell was an Irish flax farmer, who arrived in Australia with his wife Martha (born Martha Elvidge) in the 1850s. Belfast was a prosperous modern city at that time.

The area had become a specialist for farming and processing flax, which was woven into linen, used among other things for ships’ sails.

Our Little Allie 1895-1906

Late July 2007, on a clear winters day in Chiltern, a small Northern Victorian town I found myself standing by my great aunt’s graveside. Alice Martha Coates died on the 8th of October 1906, aged eleven and a half.

Thomas and Tessa had just been married at Nagambie and we were heading up the Hume Highway for a little R & R with Anne and Ben in the vineyards of Rutherglen. As we approached the turn off to Chiltern, 38k past Wangaratta where my grandfather Alfred had lived as a boy, we decided to have an ‘explore’. We turned towards Chiltern and found ourselves in the historic main street, complete with restored shopfronts, antique shops and the Historical Society, open for business.

Margaret and I, aware that our mother had been named after her, had grown up hearing our grandfather talk in hallowed tones of ‘our little Allie’ who, in our childhood memories, was almost saint like. You must remember that Margaret and I had grown up on a diet of novels such as Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, one of our favourites. In this novel Beth March, a child almost too good to be true and therefore likely not long for this world dies a lingering but saintly death, nursed by her adoring older sister. Fertile imagination conjured up such scenes as we heard the stories of little Allie's death or held the remembrance badge portraying her as a pretty, serious child. Allie died at Chiltern but that was all I knew, so into the Historical Society to find out more.

The building was slightly musty, its walls covered in old photographs and fortunately for us, as is so often the case, it was staffed by an enthusiastic and knowledgable volunteer. Yes, he knew about Reverend Alfred Coates : We think he lived in this house and yes his youngest daughter died here. After rummaging in the filing cabinet we had the location of the grave in the Chiltern Cemetery and we were able to read a newspaper report on the well attended funeral. Alice had obviously been ill for several weeks and it was no doubt a big topic of conversation in the town, especially as she was the daughter of a much loved Pastor. Maybe other children in the town were also ill in those same weeks.

Who was Alice Martha Coates, our great aunt who died aged eleven?

Our grandfather’s parents were Alfred senior, a Methodist parson, and Emma. The church chose his positions and moved the family every three years, in their case throughout country Victoria. They had four children, Florence, Alfred (our grandfather), Alice and Arthur. The photographs below show Allie with her parents and their house in Chiltern.

Allie died from the disease Diphtheria. This was a very common childhood disease of the times. Nowadays we have a vaccine for it, and antibiotics to treat it, but in those days it was one of the most feared childhood diseases.

It was highly contagious, and Emma and Alfred must have been very worried about the other children catching it. At first the symptoms are like those of a cold, but a horrible film, like a spider web, grows on the back of the throat or in the nose, and makes it hard to breathe. Alice must have had a really bad dose, because only one in ten people over five died from Diphtheria.

Armed with directions to the cemetery we politely extracted ourselves before we heard the complete history of Chiltern and stepped outside into the twenty-first century world. The cemetery is located outside the now small town, in slightly undulating country. It was chilly that day but this small country cemetery would have seen many blistering hot summer days. My thoughts turned to my grandfather: Allie’s older brother Alf, standing with his family at the graveside during the funeral. Some memories were no doubt already etched in his memory and others were forming These would combine to become the story of this tragic event passed down to us.

The little remembrance badge of Allie (shown below) lived in a wooden box on Alf’s desk. As children, we drank in the pathos of her beauty and goodness, amplified by the Victorian novels we read. The telling and retelling of little Allie’s story first by our grandfather and then our mother and aunt has helped Allie’s story retain its enduring poignancy, lifting it out of the commonplace into the world of idealised tragic heroines.

Allie’s grave is indeed in the Chiltern Cemetery, still intact. The modest headstone is there surrounded by the typical wrought iron fence of the era. The only flowers are those of the Cape Weed Daisies growing in abundance throughout the cemetery. The inscription is still legible and simply reads: Our Allie October 8th 1906. As I stood there the story suddenly seemed much more real. Allie was no longer the tragic heroine, but a little girl who died an unpleasant death, mourned by her distraught family.

I picked a small bunch of the Cape Weed daisies and placed it front of the headstone.