Box Hill

Books of Our Childhood

18 09 24 13:00 Filed in: Children 1950s

Books have always played a large part in our lives and I cannot remember a time when we have not had a book ‘on the go’. As children we grew up with books in the house. Our parents read at night when we had gone to bed.

We are three years apart, and our early childhood experiences are quite different. Despite the three year gap, when we read lists of books for little children, from those times, the same titles resonate for both of us.

As we became independent readers, home time meant being left much of the time to our own devices. The municipal library was our source of escapism, adventure and vicarious happiness.

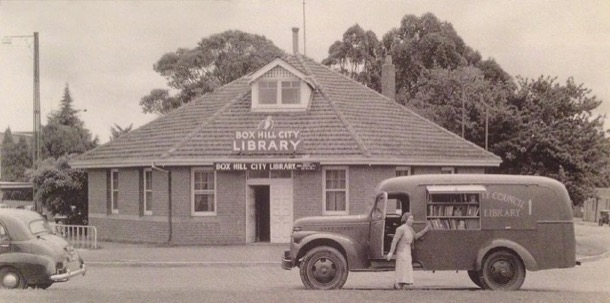

I vividly remember what I assume was a private, lending library coming to the house with blue covered hard back books for Mum and Dad to borrow. I remember the small van parked at the front door and the gentleman, clad in a fawn dust coat, bringing in the books and inserting the borrowing card in the pocket inside the back cover of items borrowed. We cannot find any reference to travelling lending libraries but we surmise that it may have been an offshoot of a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens. Public lending libraries were not established until the 1960s, in response to public pressure. Maybe when Mum and Dad lived with her parents they had all belonged to a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens, not far from Boronia Street, where they lived.

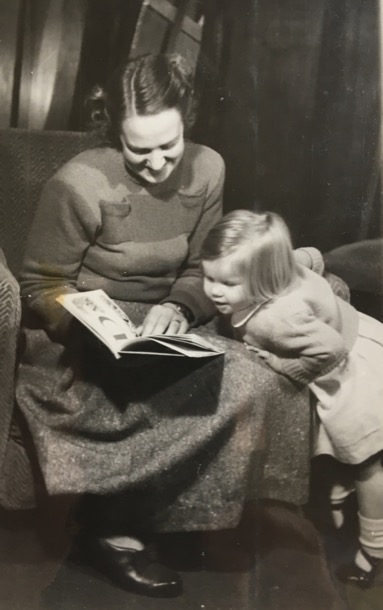

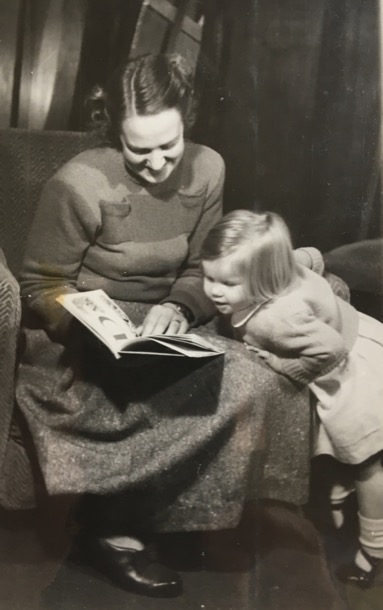

I loved having Mum read to me.

But Margaret was three years younger and her experience was completely different:

“I was just three when the next baby in line was born. He was premature and challenging, and we think our mother probably found the next few years a very difficult time.

In the years before he was born, she read to Sue, and I was there, but I don’t have much memory of it. I certainly don’t have the strong, warm connection to those books that Sue has. And when I was of an age where they would have been appropriate for me, Mum was caught up with managing the baby, and I was pretty much left to my own devices.

I remember, later on, her reading to our two younger brothers, perhaps when they were about three and five years old. But, by then I was reading for myself.”

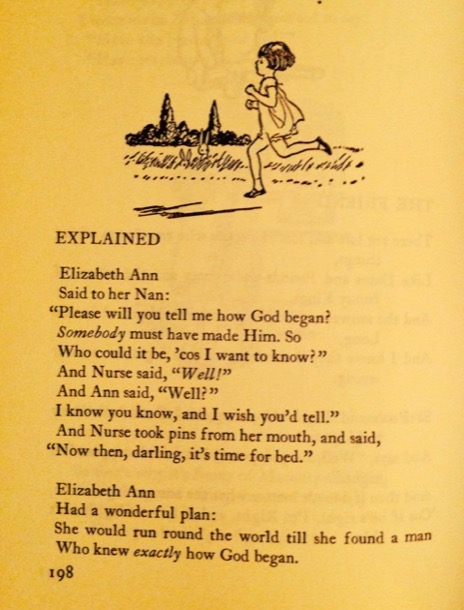

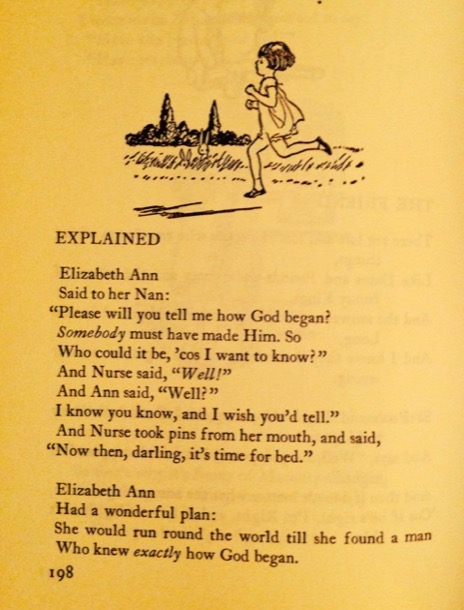

One of my earliest memories was of the A.A. Milne books. Milne wrote the story of Winnie-the-Pooh for his son, on whom the character of Christoper Robin was based.

We also had a vinyl record of the poems read by a man, with a very English accent of course. We must have listened to it hundreds of times, as Margaret and I can both recite The King’s Breakfast and some others, with exactly the same rhythm and expression.

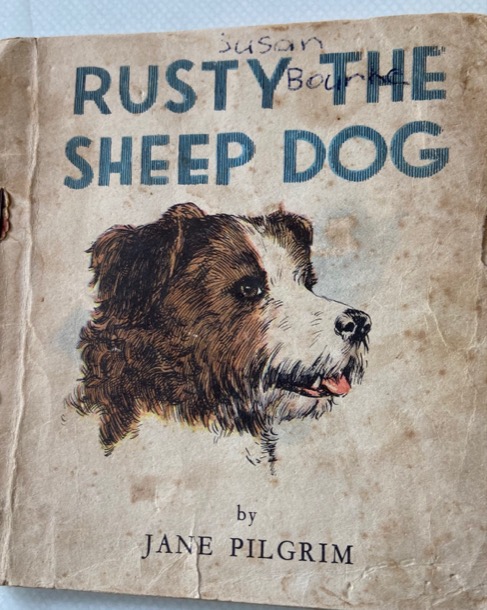

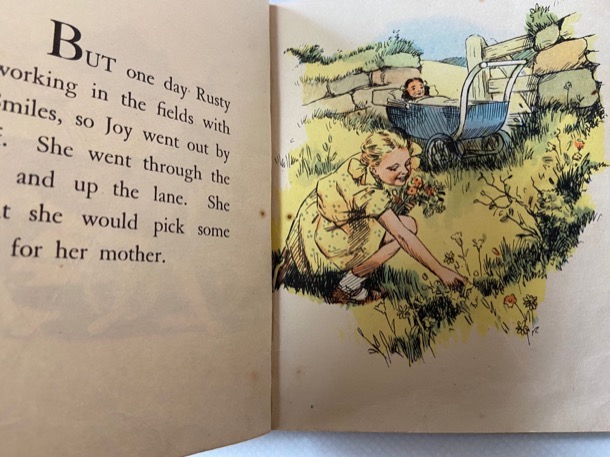

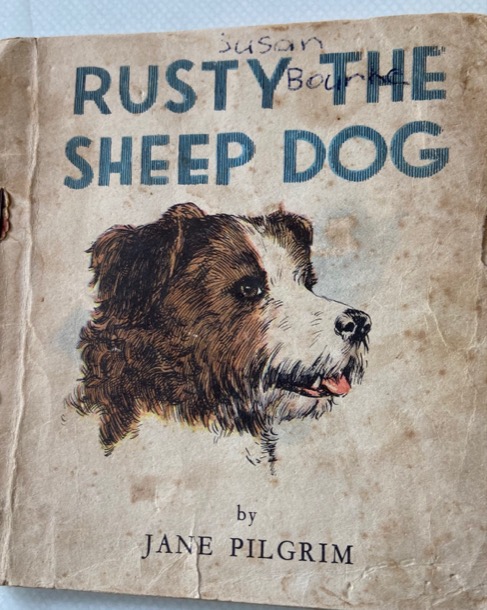

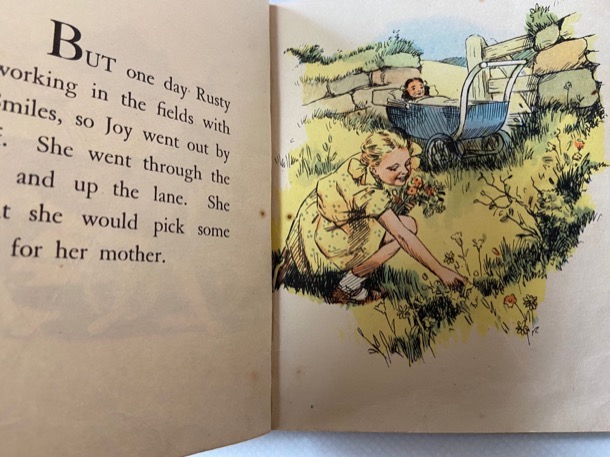

My other strong and pleasant memory is of Rusty the Sheep Dog, which is one of the Blackberry Farm series by English author Jane Pilgrim. Blackberry Farm is situated on the outskirts of an unnamed English village. The farm, a sheep and dairy property, is owned by Mr and Mrs Smiles, who have two children, Joy and Bob. Very proper, very white and very English.

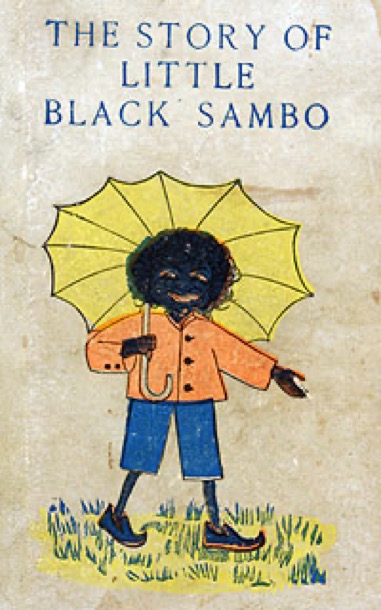

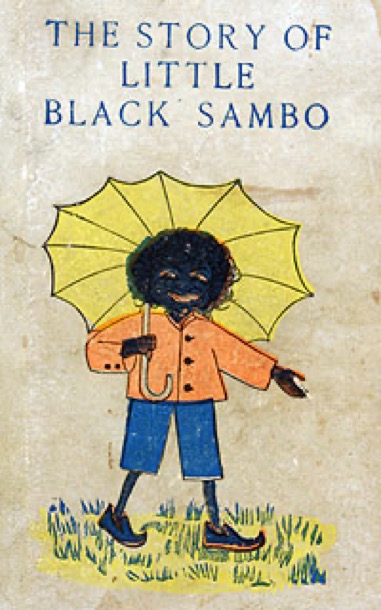

From this we graduated to Noddy and Big Ears complete with culturally inappropriate “golliwogs” and apparently a questionable relationship between Noddy and Big Ears. It all went over our heads, as did the racist overtones in Little Black Sambo. Black Sambo was a little Indian boy whose mother was Black Mumbo and father Black Jumbo.

Oh dear! Once again the stereotyping passed us by. Was it maliciously racist or a product of its times? After all, the author wrote and illustrated the book in 1889., in a Britain which had an imperialist presence in India and an Empire ‘on which the sun never sets’.

Our early schooling took place alongside a fair chunk of the population…. the baby boomers were growing up. It was still “post war” enough in the mid fifties for there to be a shortage of teachers. All this was dealt with by adding more and more desks - class sizes were massive!

The range of abilities in each class was, as always, vast. The single teacher was charged with teaching the more than fifty little souls in front of her how to read. There were no remedial classes, no gifted programs and no differentiated curriculum - sink or swim, and sit down and shut up!

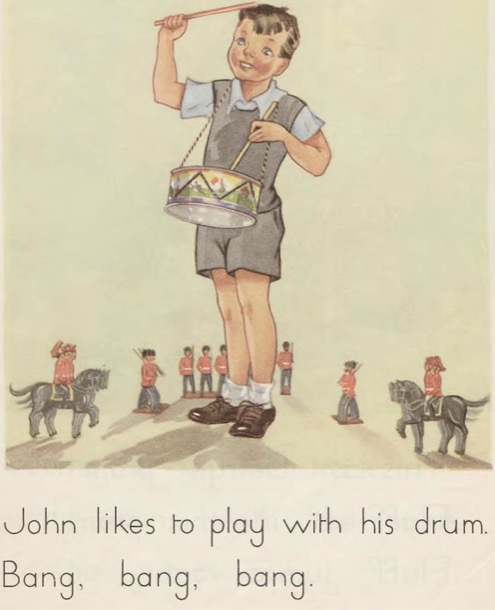

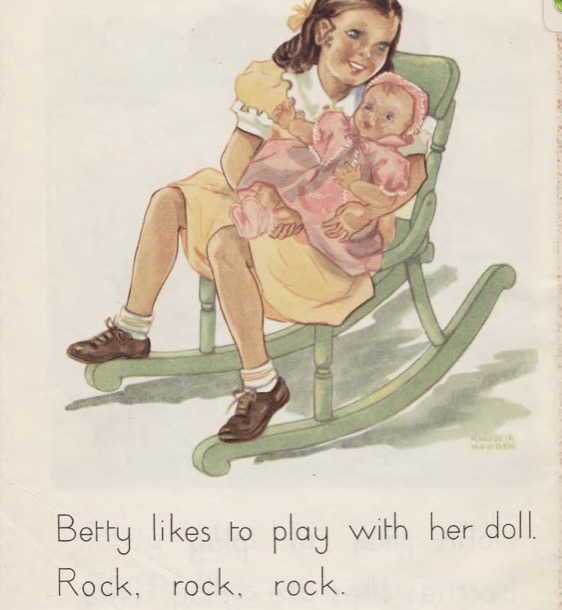

At the time we were in the early grades at school, the “whole word” system was mandated. This has the goal of having “the children recognise the word as having a particular shape or contour, rather than decode the word based on individual letter sounds.”

We remember flash cards - words, phrases and then sentences, which, in sing song little unison voices, we “read”, as the teacher held each card up.

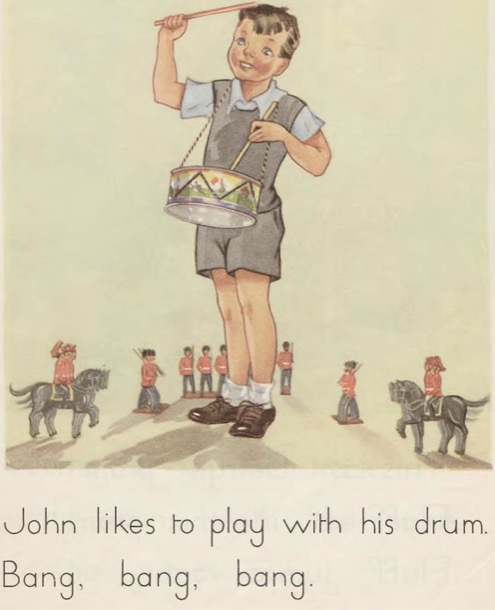

“John”

John likes”

John likes to play.”

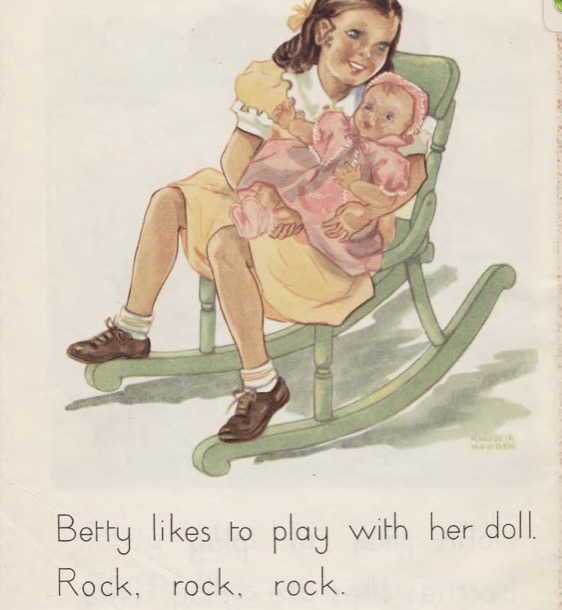

Then, eventually, we read the whole lot. John and Betty was a portrait of little siblings, stereotyped in every possible way one can stereotype!

My main memory of this time is … impatience. I don’t really know when the “being able to read” magic happened. I don’t think I could read before I went to school, but the whole process seemed very slow.

It seems we didn’t have access at school to other books, and I don’t remember reading books at home until a bit later. But I wanted to.

Eventually, enough of the class was deemed to be proficient enough at reading to read other things.

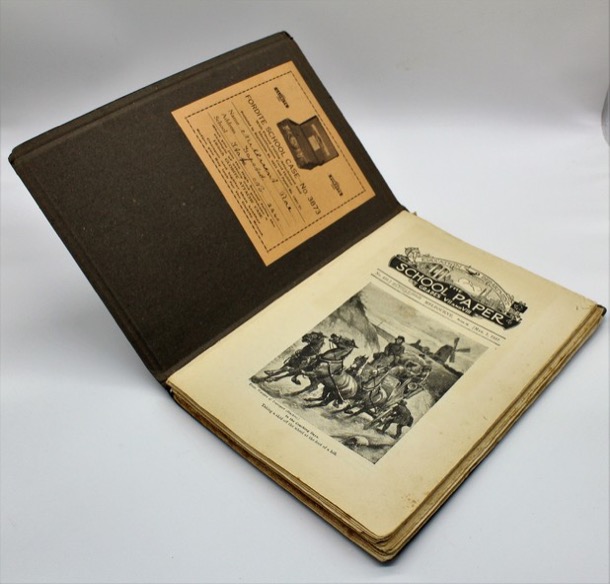

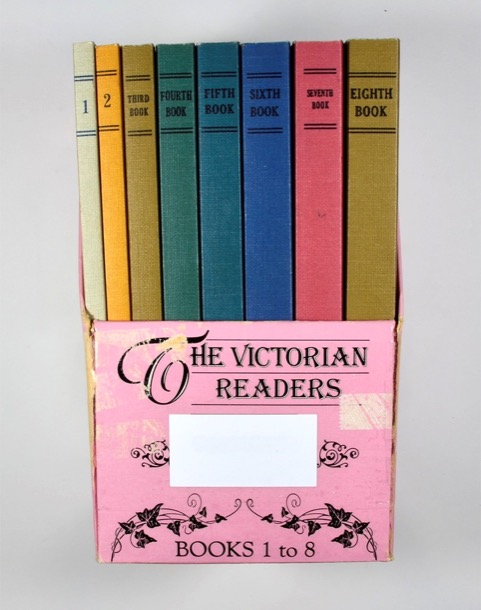

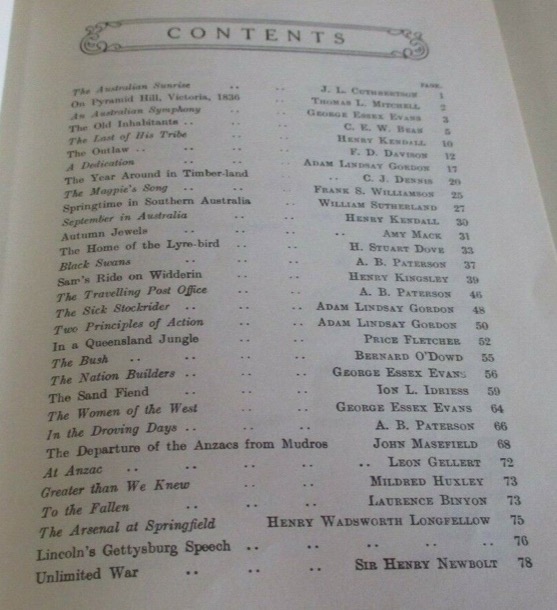

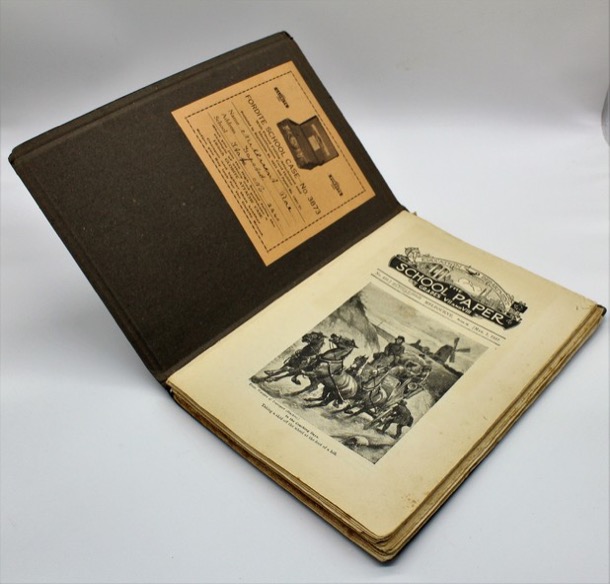

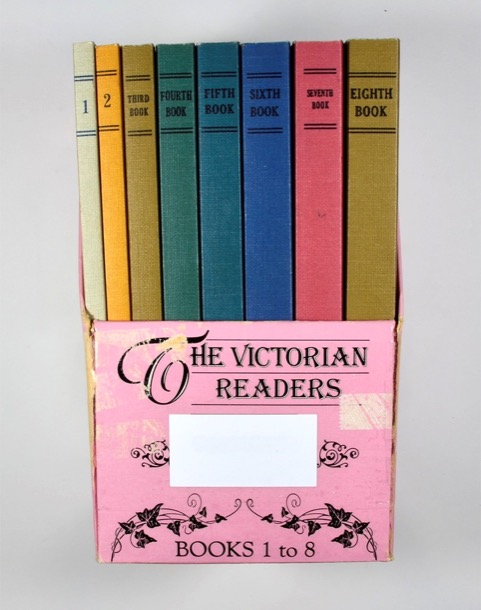

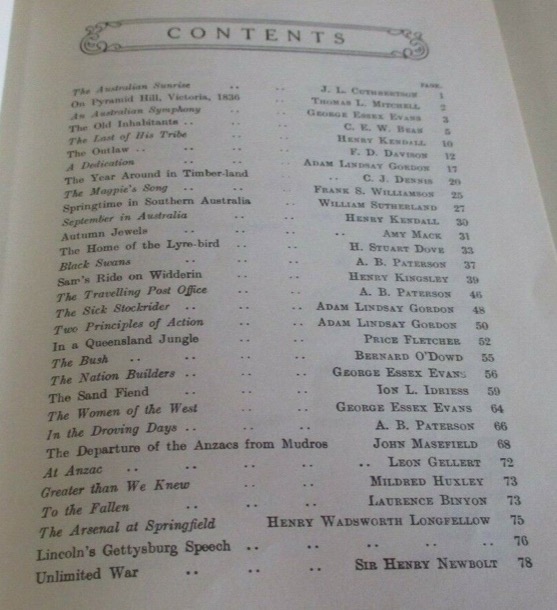

The School Paper, a monthly publication of the Victorian Education Department, was first introduced into Victorian schools in the 1890s.They were compulsory reading in schools until 1928, when the Victorian readers became compulsory and the School papers supplemented them. We remember both, and in our memory, the contents was interchangeable.

The school papers were foolscap sized, printed on fairly cheap paper. At the beginning of the year we all bought a black folder, stiffened cardboard with inner strings ready to contain the twelve issues for the year. Sue says she can remember the smell of the folders.

The readers are collections of stories, poems, illustrations and extracts from longer works, twenty-five percent of which had to be Australian. The rest has a very British flavour. The Australian content focused on white bushmen, pioneers, and settlers with a side serving of heroic Anzacs. The Australian landscape was sentimentalised, even while its “taming” was celebrated.

They are an insight into the values and culture that were being instilled into the population, and also into the standard expected at particular levels.

Clearly, quite a proportion of the class would have found the language incomprehensible, and the content alien.

We can only remember reading the School Paper and Victorian Readers at school. And we kept them in our school desk. Did we own our own copy? Did we have use of them just for the school year?

Once we could read, we had a limited, but much loved selection of books.

Enid Blyton was a staple, once again an English author. We particularly loved the Faraway Tree and Famous Five books. The Faraway Tree was a spreading oak, big enough to have small houses in the trunk. It grew in an enchanted forest and its branches reached up into magical lands, in which many of the adventures took place. Jo, Bessie and Fanny, very English children, share their adventures with the magical residents of the tree, such as Silky and Moonface.

The Famous Five also featured very English children: Julian, Dick, Anne and George [short for Georgina ] and their dog Timmy. Their adventures were much more serious and dangerous, sometimes involving criminals and lost treasure. The vast majority of the stories take place in the children’s school holidays, close to George's family home, Kirrin Cottage. The settings are almost always rural and the children picnic, bike ride and swim in the English and Welsh countryside: very wholesome.

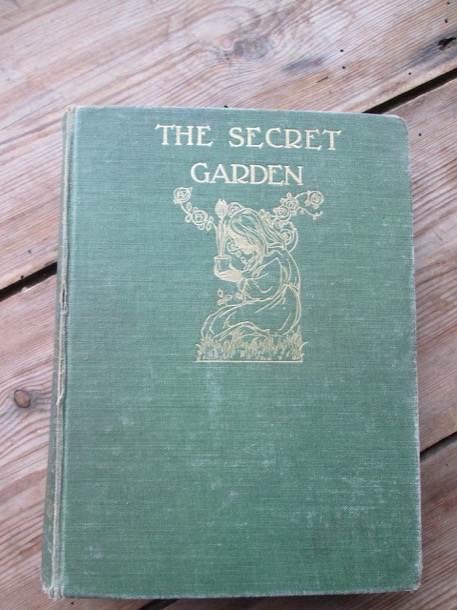

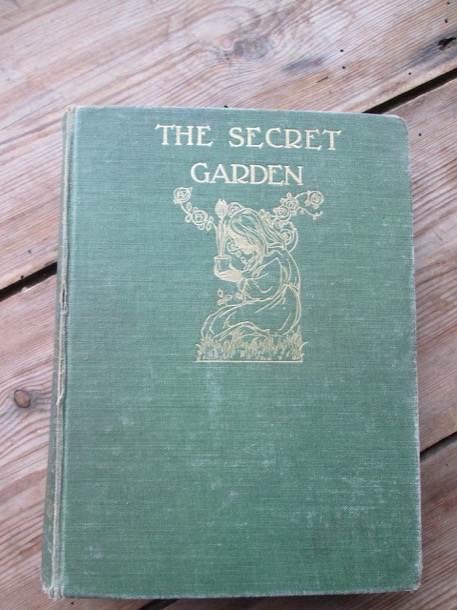

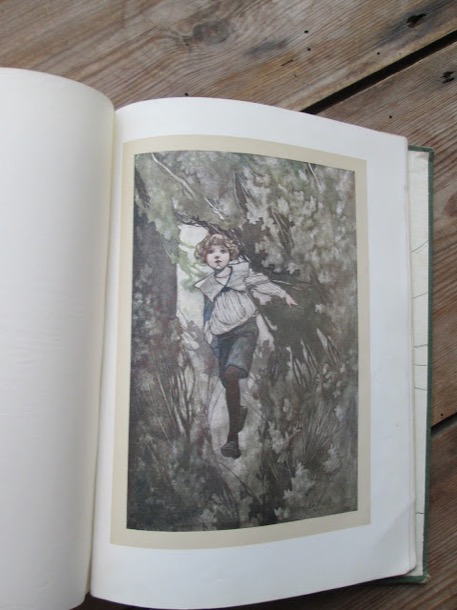

Our grandfather, Mum’s father, also revered books, many with English authors. When we were older we both remember borrowing his books such as George Elliot’s Mill on the Floss.This was a story of Tom and Maggie Tulliver, siblings who grow up at Dorlcote Mill on the River Floss. Another book from ‘the old country’ and a classic of English children’s literature was The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. We read Mum’s copy , a prize from school days. This story is set in a manor house on the Yorkshire moors where Mary Lennox is sent after her parents die in India. She has grown up in colonial India, surrounded by colour and life, and people who always do exactly what she wants, presumably Indian servants. This, like much of our reading matter, reeked of English privilege, class and the trappings of Empire.

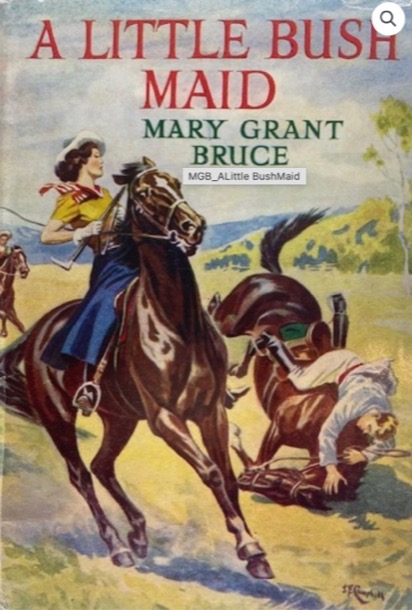

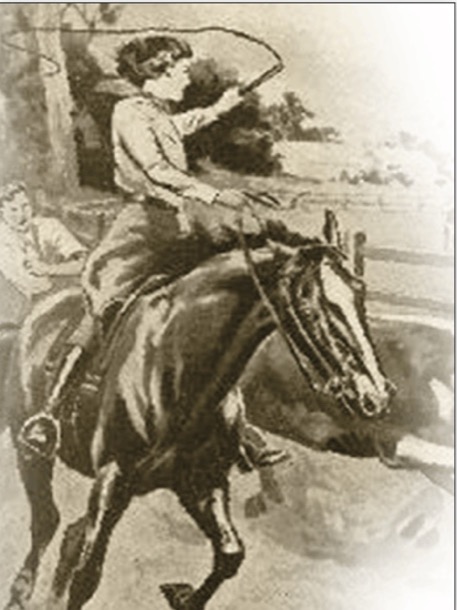

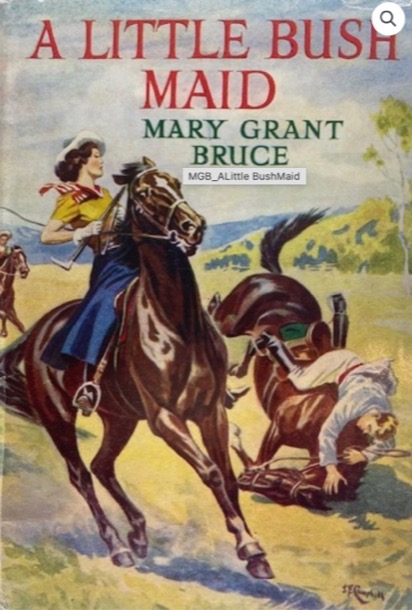

In this environment it is not surprising that Australian literature had similar characteristics. The Billabong books by Mary Grant Bruce, published in 1910, are a prime example. Very Anglo Saxon, gender specific and some would say racist, they represented to our young, innocent minds, adventure, and a glimpse into an idyllic life on a prosperous large property somewhere in Victoria. Twelve year old Norah, the ‘little bush maid’ lives at Billabong Station with her widowed father and brother Jim. Norah rides all over the property on her beloved pony Bobs, joining in the mustering and the “holiday fun” when Jim comes home from boarding school.

This sums up our own reaction to the Billabong books:

‘The Linton family are very much lords of their Australian manor, ruling in a benignly patronising way.The house, large enough to have ‘wings’, is staffed by a doting cook and various ‘girls’. The decorative front garden is maintained by a Scotsman, the vegetable garden and orchard at the rear are looked after by ‘Chinese Lee Wing (and oh isn’t his silly accent funny!) Numerous unnamed men work the farm itself with one of them, called Billy, seemingly assigned to be the children’s personal slave. Billy is never, ever described without with an adjective like “Sable Billy” or “Dusky Billy” or “Black”. And in case the reader hadn’t quite caught on, he is also variously described as careless, lazy or – just once – as a n——r. At 18 years of age Billy is older than the children and, according to Norah’s father, the best hand with a horse he’d ever seen, yet the children casually order him about and call him Boy. Billy, like every 18 year old bossed by a 12 year old girl, living without friends or family, and with no girlfriend in sight, seems perfectly content with his lot.

But, and sadly there always seems to be a but, my beloved Billabong books belong very much to the era in which they were written. Almost every writer I know cites Enid Blyton as one of their favourite childhood authors. She transported them in a way few other writers could. But almost every writer I know is also sorrowfully aware that once you’ve grown up there is no going back to Blyton’s magical worlds. The racism, the class barriers, the gender stereotypes are just too distressingly obvious to make Blyton an enjoyable adult read. And so it is for Billabong.’

Michelle Scott Tucker [Billabong Series, Mary Grant Bruce 2019]

As well as books, there were magazines.

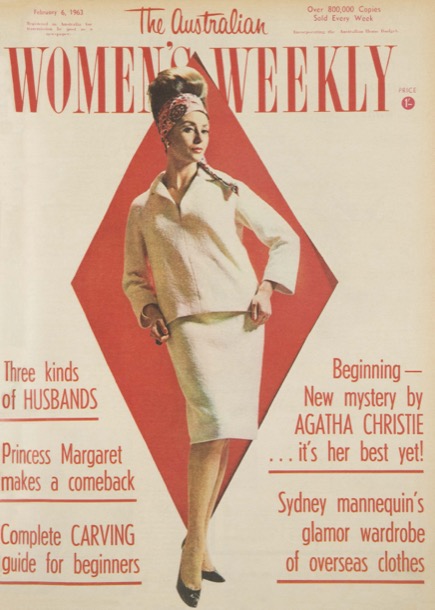

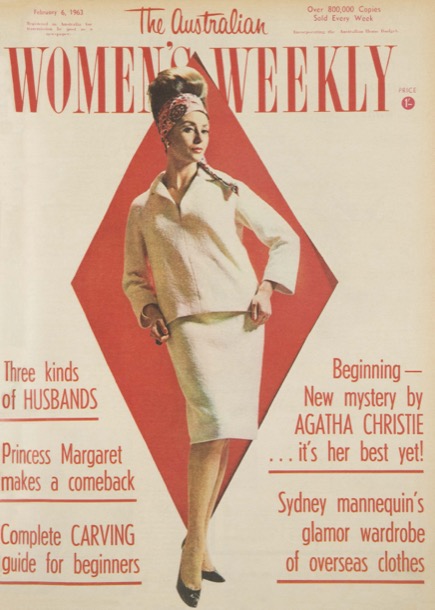

We struggle to remember exactly how frequently we got the Woman’s Weekly magazine. It came out weekly, until 1982, when it became a monthly. We think our mother must have bought occasional ones from the Wattle Park Newsagent. We don’t think we had a subscription, but it is a very clear memory.

It was an important window into Australian suburban culture.

We remember the sections:

Agony aunt, where people would write in asking for relationship advice.

Household hints

Letters

Knitting and sewing patterns

Fashion and make up advice

Recipes

Health items, discussion specifically about women and children

Probably some Hollywood celebrity items, but we don’t remember having much interest in those

Royals. That was much more our cup of tea. After all, our second names are the names of the late queen and her daughter.

… and of course the ads - mostly household items, fashion and make up.

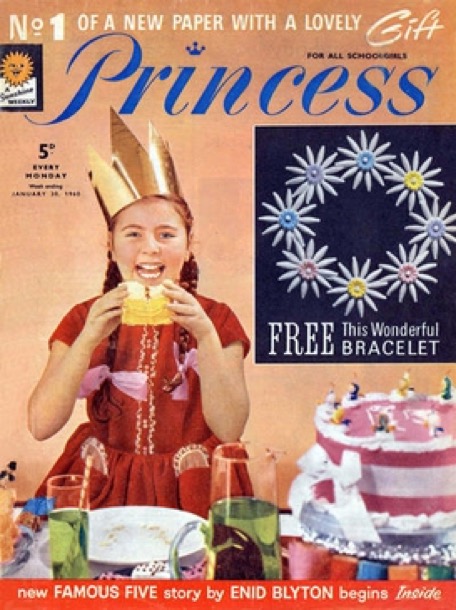

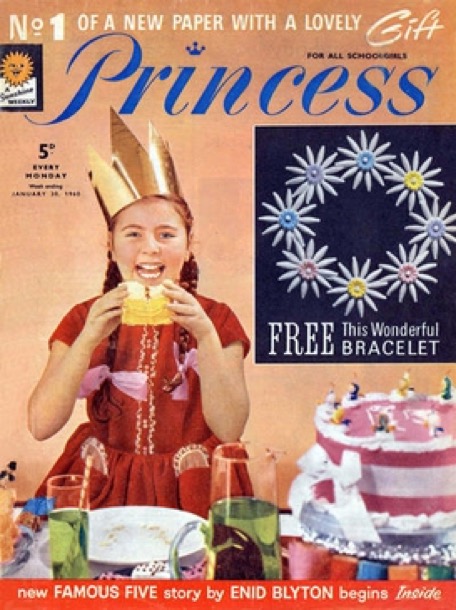

From January 1960, when I was eight and Sue was eleven, we had Princess magazine, a monthly English magazine, aimed at middle class girls. It contained stories, serials, factual articles, all with high quality photos and pictures. Ballet, horses and show jumping, fashion… the content did not have much to do with our own lives, but maybe that’s why we loved it. And there were free gifts!

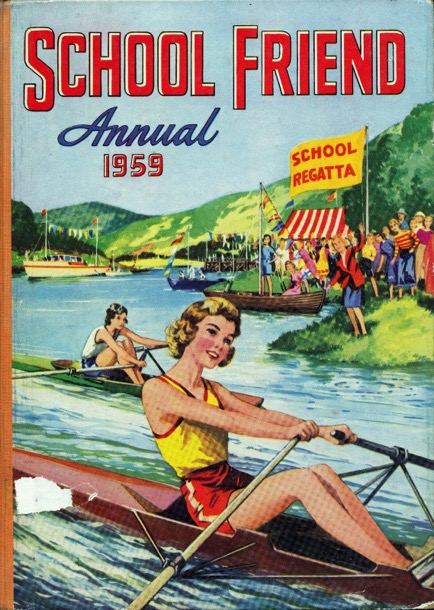

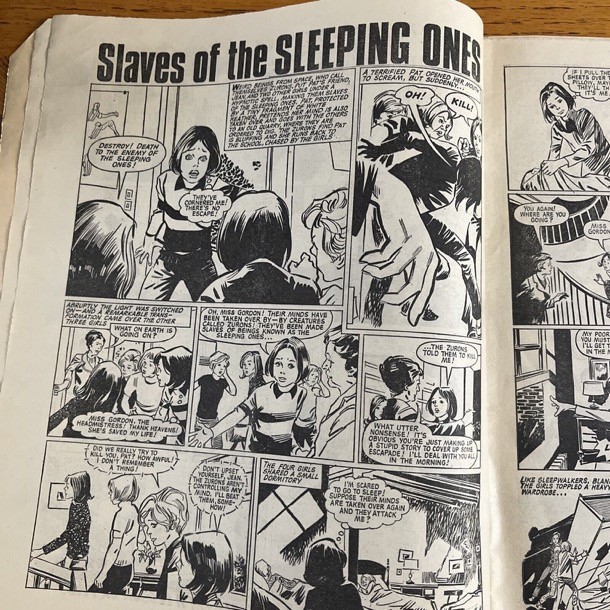

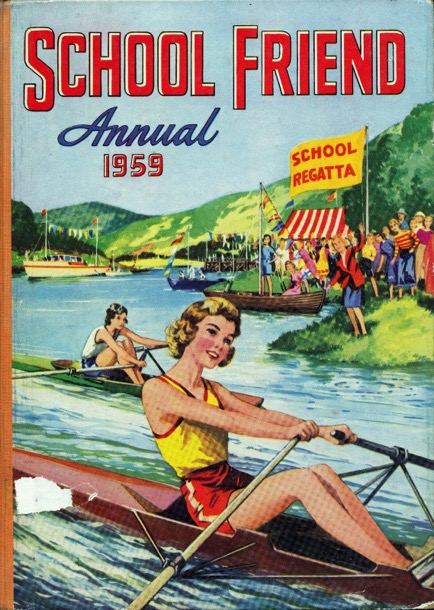

We also loved Schoolfriend magazine and Annuals.

‘Schoolfriend was about the exploits of brave, public school girls at boarding school in England, based on the adventures of pupils in a girls’ boarding school called Cliff House, and featured such characters as Barbara Redfern, Mabel Lyon, Jemima Carstairs – who wore a monocle and had an Eton crop’.

Although the stories featured scenarios in which most children wouldn’t have participated in the 1950s (horse riding, ballet, skiing in the Alps) there was an interesting message being spelled out: in a school environment devoid of males, females were able to assert themselves and reach their full potential.’

from https://johndabell.com/

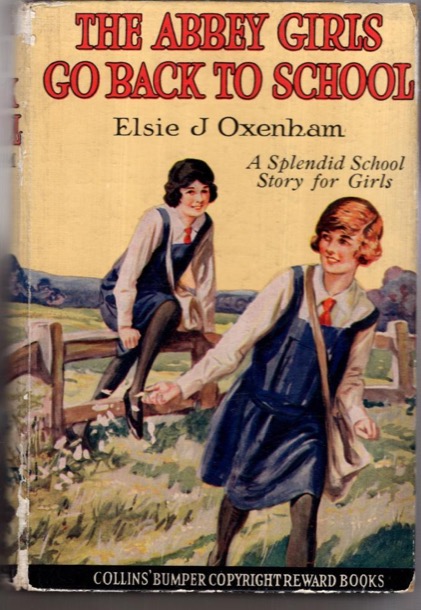

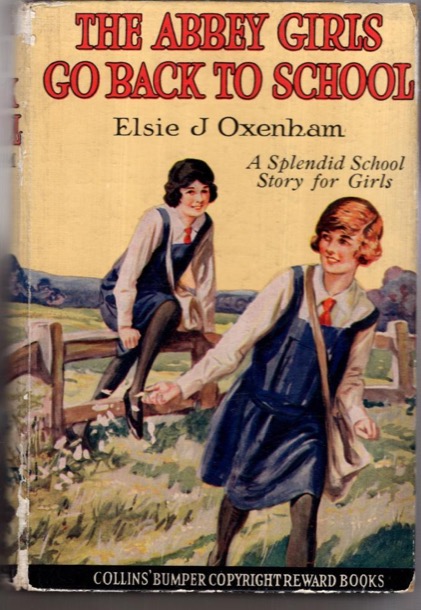

There were English Boarding School books, too.

During our annual six week Christmas holiday camping holidays, reading featured heavily.

My memory is of many nights with the family sitting around in the tent, under the central tilley lamp, wrapped in blankets, reading, in silence. When we look at the timing, it probably only happened for a few years, and it would not have included our little brothers, but it feels like a well established custom.

The books lived in a sturdy wooden box, the “book box”, which, Sue remembers, had dovetailed joints. In my memory, we all dipped into it. Maybe our younger brothers were in bed, or maybe they read other, more suitable books. We don’t remember them being read to.

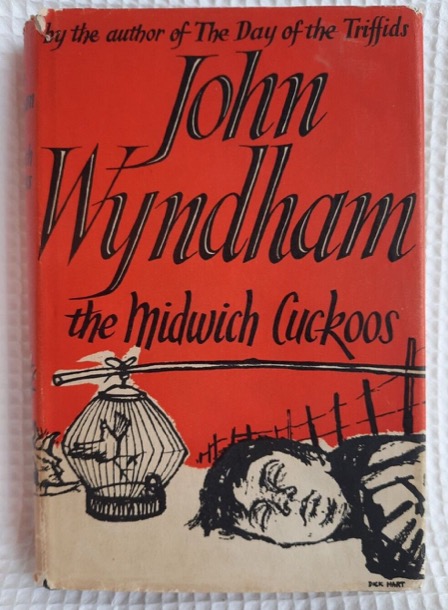

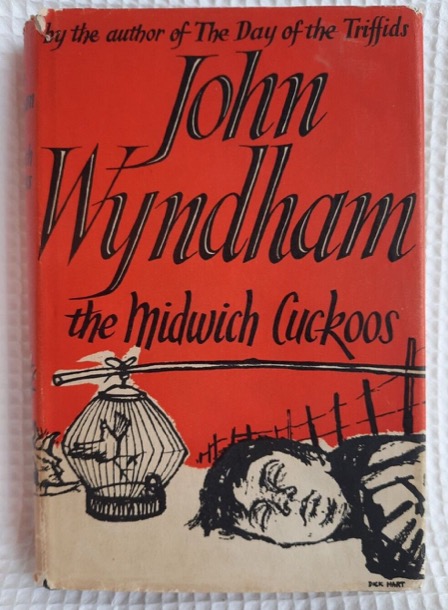

There were a lot of library books, but paper backs featured as well. A brainstorm yields: P D James, Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh and other “who dunnits”, Gerald Durrell’s family stories, AJ Cronin, John Wyndham’s Science fiction, Dr Kildare books.

In general, it’s holiday reading, and pretty light. We remember the books being mostly our father’s choice. There were some we didn’t like, such as Westerns, with pictures on the cover of cowboys on horseback. We don’t remember any censorship, but maybe it was subtle enough for us not to have noticed.

Camping holidays are the only time either of us can remember reading Mum and Dad’s books. We can’t ever remember not having access to books though. As a family we didn’t own many books, we all used the library.

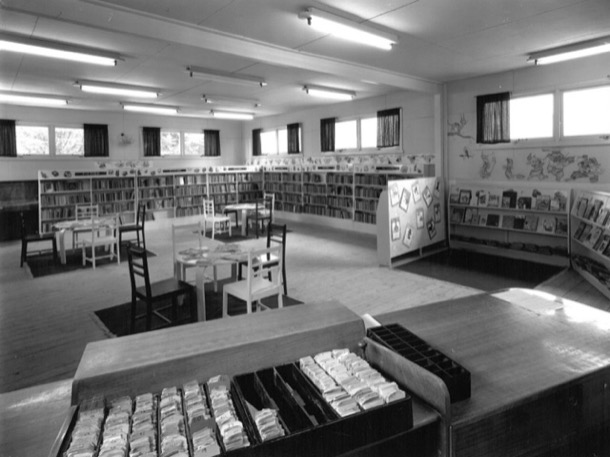

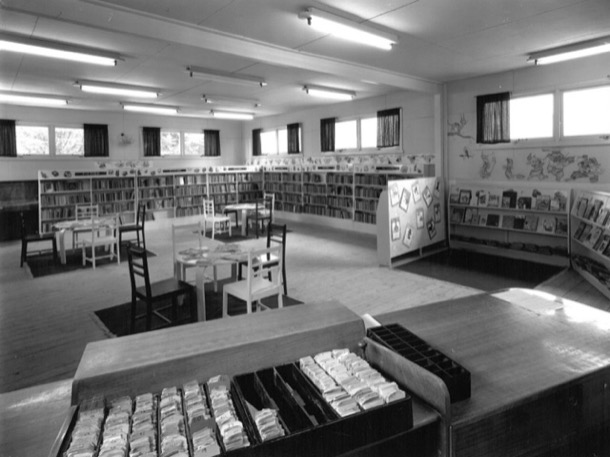

Visits to the Box Hill Junior Library were a regular feature in our childhood. The library was behind the Town Hall and was a very simple weatherboard structure, but inside it seemed there was a never ending supply of books. I never remember not being able to find a book I liked. Library visits must have been fortnightly as that was the borrowing period, so it is no wonder that I can still visualise the interior exactly.

The Billabong books were on the right just past the picture books, top and second shelf down. Once in the door, we would always make a beeline for that shelf to see if the next Billabong book was there. This was particularly important to me as I wanted to read them in order. Margaret does not remember this being a feature of her library visits.

We began this exploration of books in our early life full of the warm memories of specific titles. We already knew that, in our childhood, books were our escape, our entertainment and our cultural education. We buried ourselves in books, and we both remember many hours reading on our beds transported to other worlds.

Over the time we have been talking and writing about this topic, we have realised that the genre that most captured our imagination, and has remained as treasured memories, was actually quite narrow. It was characterised by adventure, characters who were resourceful and brave, often female, and idyllic settings. The action often happened in school holidays, sometimes on islands and beaches or Australian cattle and sheep stations.

We are also struck by the narrowness of the cultural values. We think of our family’s values as progressive, liberal and inclusive. We witnessed no open discrimination in our white suburban neighbourhood. And now, we are surprised at the extent of the sexism, class prejudice and racism in beloved books. It all went completely unnoticed at the time, but our adult, twenty-first century eyes look aghast at the world we immersed ourselves in.

We are three years apart, and our early childhood experiences are quite different. Despite the three year gap, when we read lists of books for little children, from those times, the same titles resonate for both of us.

As we became independent readers, home time meant being left much of the time to our own devices. The municipal library was our source of escapism, adventure and vicarious happiness.

I vividly remember what I assume was a private, lending library coming to the house with blue covered hard back books for Mum and Dad to borrow. I remember the small van parked at the front door and the gentleman, clad in a fawn dust coat, bringing in the books and inserting the borrowing card in the pocket inside the back cover of items borrowed. We cannot find any reference to travelling lending libraries but we surmise that it may have been an offshoot of a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens. Public lending libraries were not established until the 1960s, in response to public pressure. Maybe when Mum and Dad lived with her parents they had all belonged to a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens, not far from Boronia Street, where they lived.

I loved having Mum read to me.

But Margaret was three years younger and her experience was completely different:

“I was just three when the next baby in line was born. He was premature and challenging, and we think our mother probably found the next few years a very difficult time.

In the years before he was born, she read to Sue, and I was there, but I don’t have much memory of it. I certainly don’t have the strong, warm connection to those books that Sue has. And when I was of an age where they would have been appropriate for me, Mum was caught up with managing the baby, and I was pretty much left to my own devices.

I remember, later on, her reading to our two younger brothers, perhaps when they were about three and five years old. But, by then I was reading for myself.”

One of my earliest memories was of the A.A. Milne books. Milne wrote the story of Winnie-the-Pooh for his son, on whom the character of Christoper Robin was based.

We also had a vinyl record of the poems read by a man, with a very English accent of course. We must have listened to it hundreds of times, as Margaret and I can both recite The King’s Breakfast and some others, with exactly the same rhythm and expression.

My other strong and pleasant memory is of Rusty the Sheep Dog, which is one of the Blackberry Farm series by English author Jane Pilgrim. Blackberry Farm is situated on the outskirts of an unnamed English village. The farm, a sheep and dairy property, is owned by Mr and Mrs Smiles, who have two children, Joy and Bob. Very proper, very white and very English.

From this we graduated to Noddy and Big Ears complete with culturally inappropriate “golliwogs” and apparently a questionable relationship between Noddy and Big Ears. It all went over our heads, as did the racist overtones in Little Black Sambo. Black Sambo was a little Indian boy whose mother was Black Mumbo and father Black Jumbo.

Oh dear! Once again the stereotyping passed us by. Was it maliciously racist or a product of its times? After all, the author wrote and illustrated the book in 1889., in a Britain which had an imperialist presence in India and an Empire ‘on which the sun never sets’.

Our early schooling took place alongside a fair chunk of the population…. the baby boomers were growing up. It was still “post war” enough in the mid fifties for there to be a shortage of teachers. All this was dealt with by adding more and more desks - class sizes were massive!

The range of abilities in each class was, as always, vast. The single teacher was charged with teaching the more than fifty little souls in front of her how to read. There were no remedial classes, no gifted programs and no differentiated curriculum - sink or swim, and sit down and shut up!

At the time we were in the early grades at school, the “whole word” system was mandated. This has the goal of having “the children recognise the word as having a particular shape or contour, rather than decode the word based on individual letter sounds.”

We remember flash cards - words, phrases and then sentences, which, in sing song little unison voices, we “read”, as the teacher held each card up.

“John”

John likes”

John likes to play.”

Then, eventually, we read the whole lot. John and Betty was a portrait of little siblings, stereotyped in every possible way one can stereotype!

My main memory of this time is … impatience. I don’t really know when the “being able to read” magic happened. I don’t think I could read before I went to school, but the whole process seemed very slow.

It seems we didn’t have access at school to other books, and I don’t remember reading books at home until a bit later. But I wanted to.

Eventually, enough of the class was deemed to be proficient enough at reading to read other things.

The School Paper, a monthly publication of the Victorian Education Department, was first introduced into Victorian schools in the 1890s.They were compulsory reading in schools until 1928, when the Victorian readers became compulsory and the School papers supplemented them. We remember both, and in our memory, the contents was interchangeable.

The school papers were foolscap sized, printed on fairly cheap paper. At the beginning of the year we all bought a black folder, stiffened cardboard with inner strings ready to contain the twelve issues for the year. Sue says she can remember the smell of the folders.

The readers are collections of stories, poems, illustrations and extracts from longer works, twenty-five percent of which had to be Australian. The rest has a very British flavour. The Australian content focused on white bushmen, pioneers, and settlers with a side serving of heroic Anzacs. The Australian landscape was sentimentalised, even while its “taming” was celebrated.

They are an insight into the values and culture that were being instilled into the population, and also into the standard expected at particular levels.

Clearly, quite a proportion of the class would have found the language incomprehensible, and the content alien.

We can only remember reading the School Paper and Victorian Readers at school. And we kept them in our school desk. Did we own our own copy? Did we have use of them just for the school year?

Once we could read, we had a limited, but much loved selection of books.

Enid Blyton was a staple, once again an English author. We particularly loved the Faraway Tree and Famous Five books. The Faraway Tree was a spreading oak, big enough to have small houses in the trunk. It grew in an enchanted forest and its branches reached up into magical lands, in which many of the adventures took place. Jo, Bessie and Fanny, very English children, share their adventures with the magical residents of the tree, such as Silky and Moonface.

The Famous Five also featured very English children: Julian, Dick, Anne and George [short for Georgina ] and their dog Timmy. Their adventures were much more serious and dangerous, sometimes involving criminals and lost treasure. The vast majority of the stories take place in the children’s school holidays, close to George's family home, Kirrin Cottage. The settings are almost always rural and the children picnic, bike ride and swim in the English and Welsh countryside: very wholesome.

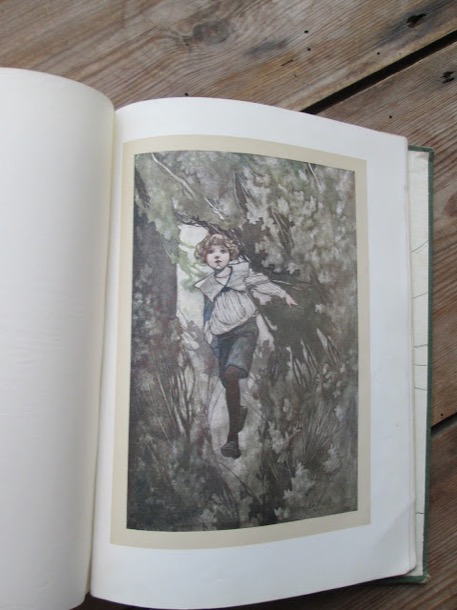

Our grandfather, Mum’s father, also revered books, many with English authors. When we were older we both remember borrowing his books such as George Elliot’s Mill on the Floss.This was a story of Tom and Maggie Tulliver, siblings who grow up at Dorlcote Mill on the River Floss. Another book from ‘the old country’ and a classic of English children’s literature was The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. We read Mum’s copy , a prize from school days. This story is set in a manor house on the Yorkshire moors where Mary Lennox is sent after her parents die in India. She has grown up in colonial India, surrounded by colour and life, and people who always do exactly what she wants, presumably Indian servants. This, like much of our reading matter, reeked of English privilege, class and the trappings of Empire.

In this environment it is not surprising that Australian literature had similar characteristics. The Billabong books by Mary Grant Bruce, published in 1910, are a prime example. Very Anglo Saxon, gender specific and some would say racist, they represented to our young, innocent minds, adventure, and a glimpse into an idyllic life on a prosperous large property somewhere in Victoria. Twelve year old Norah, the ‘little bush maid’ lives at Billabong Station with her widowed father and brother Jim. Norah rides all over the property on her beloved pony Bobs, joining in the mustering and the “holiday fun” when Jim comes home from boarding school.

This sums up our own reaction to the Billabong books:

‘The Linton family are very much lords of their Australian manor, ruling in a benignly patronising way.The house, large enough to have ‘wings’, is staffed by a doting cook and various ‘girls’. The decorative front garden is maintained by a Scotsman, the vegetable garden and orchard at the rear are looked after by ‘Chinese Lee Wing (and oh isn’t his silly accent funny!) Numerous unnamed men work the farm itself with one of them, called Billy, seemingly assigned to be the children’s personal slave. Billy is never, ever described without with an adjective like “Sable Billy” or “Dusky Billy” or “Black”. And in case the reader hadn’t quite caught on, he is also variously described as careless, lazy or – just once – as a n——r. At 18 years of age Billy is older than the children and, according to Norah’s father, the best hand with a horse he’d ever seen, yet the children casually order him about and call him Boy. Billy, like every 18 year old bossed by a 12 year old girl, living without friends or family, and with no girlfriend in sight, seems perfectly content with his lot.

But, and sadly there always seems to be a but, my beloved Billabong books belong very much to the era in which they were written. Almost every writer I know cites Enid Blyton as one of their favourite childhood authors. She transported them in a way few other writers could. But almost every writer I know is also sorrowfully aware that once you’ve grown up there is no going back to Blyton’s magical worlds. The racism, the class barriers, the gender stereotypes are just too distressingly obvious to make Blyton an enjoyable adult read. And so it is for Billabong.’

Michelle Scott Tucker [Billabong Series, Mary Grant Bruce 2019]

As well as books, there were magazines.

We struggle to remember exactly how frequently we got the Woman’s Weekly magazine. It came out weekly, until 1982, when it became a monthly. We think our mother must have bought occasional ones from the Wattle Park Newsagent. We don’t think we had a subscription, but it is a very clear memory.

It was an important window into Australian suburban culture.

We remember the sections:

Agony aunt, where people would write in asking for relationship advice.

Household hints

Letters

Knitting and sewing patterns

Fashion and make up advice

Recipes

Health items, discussion specifically about women and children

Probably some Hollywood celebrity items, but we don’t remember having much interest in those

Royals. That was much more our cup of tea. After all, our second names are the names of the late queen and her daughter.

… and of course the ads - mostly household items, fashion and make up.

From January 1960, when I was eight and Sue was eleven, we had Princess magazine, a monthly English magazine, aimed at middle class girls. It contained stories, serials, factual articles, all with high quality photos and pictures. Ballet, horses and show jumping, fashion… the content did not have much to do with our own lives, but maybe that’s why we loved it. And there were free gifts!

We also loved Schoolfriend magazine and Annuals.

‘Schoolfriend was about the exploits of brave, public school girls at boarding school in England, based on the adventures of pupils in a girls’ boarding school called Cliff House, and featured such characters as Barbara Redfern, Mabel Lyon, Jemima Carstairs – who wore a monocle and had an Eton crop’.

Although the stories featured scenarios in which most children wouldn’t have participated in the 1950s (horse riding, ballet, skiing in the Alps) there was an interesting message being spelled out: in a school environment devoid of males, females were able to assert themselves and reach their full potential.’

from https://johndabell.com/

There were English Boarding School books, too.

During our annual six week Christmas holiday camping holidays, reading featured heavily.

My memory is of many nights with the family sitting around in the tent, under the central tilley lamp, wrapped in blankets, reading, in silence. When we look at the timing, it probably only happened for a few years, and it would not have included our little brothers, but it feels like a well established custom.

The books lived in a sturdy wooden box, the “book box”, which, Sue remembers, had dovetailed joints. In my memory, we all dipped into it. Maybe our younger brothers were in bed, or maybe they read other, more suitable books. We don’t remember them being read to.

There were a lot of library books, but paper backs featured as well. A brainstorm yields: P D James, Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh and other “who dunnits”, Gerald Durrell’s family stories, AJ Cronin, John Wyndham’s Science fiction, Dr Kildare books.

In general, it’s holiday reading, and pretty light. We remember the books being mostly our father’s choice. There were some we didn’t like, such as Westerns, with pictures on the cover of cowboys on horseback. We don’t remember any censorship, but maybe it was subtle enough for us not to have noticed.

Camping holidays are the only time either of us can remember reading Mum and Dad’s books. We can’t ever remember not having access to books though. As a family we didn’t own many books, we all used the library.

Visits to the Box Hill Junior Library were a regular feature in our childhood. The library was behind the Town Hall and was a very simple weatherboard structure, but inside it seemed there was a never ending supply of books. I never remember not being able to find a book I liked. Library visits must have been fortnightly as that was the borrowing period, so it is no wonder that I can still visualise the interior exactly.

The Billabong books were on the right just past the picture books, top and second shelf down. Once in the door, we would always make a beeline for that shelf to see if the next Billabong book was there. This was particularly important to me as I wanted to read them in order. Margaret does not remember this being a feature of her library visits.

We began this exploration of books in our early life full of the warm memories of specific titles. We already knew that, in our childhood, books were our escape, our entertainment and our cultural education. We buried ourselves in books, and we both remember many hours reading on our beds transported to other worlds.

Over the time we have been talking and writing about this topic, we have realised that the genre that most captured our imagination, and has remained as treasured memories, was actually quite narrow. It was characterised by adventure, characters who were resourceful and brave, often female, and idyllic settings. The action often happened in school holidays, sometimes on islands and beaches or Australian cattle and sheep stations.

We are also struck by the narrowness of the cultural values. We think of our family’s values as progressive, liberal and inclusive. We witnessed no open discrimination in our white suburban neighbourhood. And now, we are surprised at the extent of the sexism, class prejudice and racism in beloved books. It all went completely unnoticed at the time, but our adult, twenty-first century eyes look aghast at the world we immersed ourselves in.

Comments

The Built Environment - Box Hill

We grew up in Box Hill South in close proximity to Surrey Hills where our family has had an association for five generations. 28 Moore Street was our family home.We all spent our childhood and early adult years there, before moving out on our own. The family ventured out into Box Hill in 1946 when our parents bought a block of land in a new subdivision. They paid one hundred pounds plus ten pounds in taxes. Jim and Alice also looked further out in Donvale, where, for a fraction of the cost, they could have purchased two acres of bush. Unfortunately this was not an option as there was no public transport and we did not own a car.

After the war, Box Hill South was opened up for new housing. The City of Box Hill revised its land valuation system and residential subdivision started to boom across the municipality. The small holdings of mixed farming and orchards, were quickly replaced by the unmade road network of the subdivisions. Electricity and gas were provided, but no sewerage until the 1950’s, so it was outside toilets for all.

Our parents could not afford to have the house built, so Jim decided to build it himself. He bought a book on basic carpentry and the tools, all hand tools of course, and proceeded to build. The house is still there today, straight as a die.

It was a very liveable and rather nice design, set on stumps, weatherboard cladding and with a low slung, pitched roof. It had the standard three bedrooms ,one bathroom, kitchen, dining room, lounge room and laundry. When first built there was an outside toilet attached to the single garage that also had a chook pen attached to it.

Over time, the surrounding paddocks filled with houses and our house changed a little too. The view of the Dandenongs from the french doors in the lounge room disappeared, the toilet moved inside and our grandparents built a flat on the back. The addition of the rumpus room and flat spoilt the spaciousness of the living rooms and the back garden. The old weatherboard garage, toilet and chook pen were removed and a new double garage and new chook pen took the new additions to the back fence.

Little appears to have changed externally to the house since Mum sold it about 1981.

When we were children, Wattle Park itself consisted of large trees with mown grass underneath, like a traditional park, but with native trees and grasses. It was owned and maintained by the Tramways Board, responsible for the tram system in Melbourne. The Tramways brass band played in a rotunda every Sunday in the park. Nowadays those grasses are no longer mown. It looks much more like remnant bushland.

The 137 acres opened as a public park in 1917.

The chalet, designed and built by a Tramways architect, opened in 1928. it was promoted as a dance hall and wedding reception venue and, amazingly, it still is. It is listed on both the Heritage Victoria and National Trust Registers.

Our own parents’ wedding reception was held there in 1945, after they had been married at the Wyclif Surrey Hills Congregationalist Church in Surrey Hills.

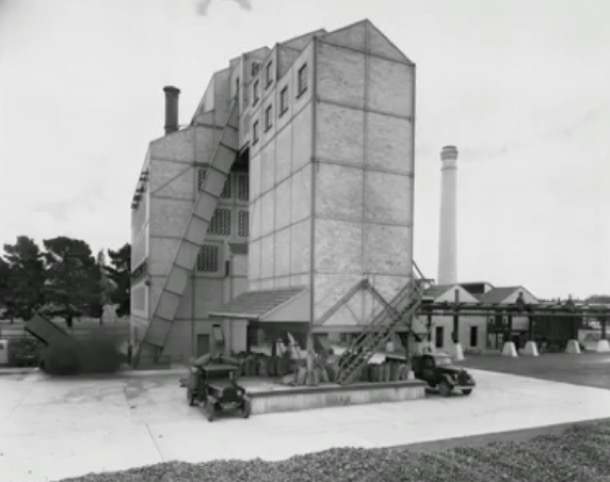

Box Hill Gasworks is now gone, but it was an important part of our parents' history. It was built early in the history of Box Hill:

7/1/1890 The Argus

Some twelve months ago the Nunawading and Boroondara councils granted permission to Mr. Thomas Coates, hydraulic engineer, to lay down gas mains in the streets of the two shires. Mr. Coates purchased an eligible site near Elgar road, Box Hill, upon which to erect the gasometer and the other necessary buildings. At the present time all the mains have been laid down in the shires named, and Mr. Coates is now in a position to light up Surrey Hills and Box Hill with gas. The local works are of such a nature that Mr. Coates contemplates being able to supply the wants of the district for many years to come without enlarging the gasworks. Last night a trial was made in Box Hill and Surrey Hills, when the corporation lamps were lit with gas for the first time. Illumination works were erected at the intersection of the leading streets. The trial was considered a very favourable one, the gas burning bright and clear. In connection with the lighting of these shires with gas a public banquet will be held in Surrey Hills next Monday night.

Over time three gasometers were built.

We don't know exactly when Jim started work at the Box Hill Gasworks, but in 1945 he left the Maribinong Munitions factory, where he had spent the war years. It was that year when our parents married and Jim moved into his in-laws’ Surrey Hills house. Soon after, he started work at the gas works as an analytical chemist. He worked there until began teaching in 1954.

Sue remembers him riding his bicycle to work, and later, a motorbike.

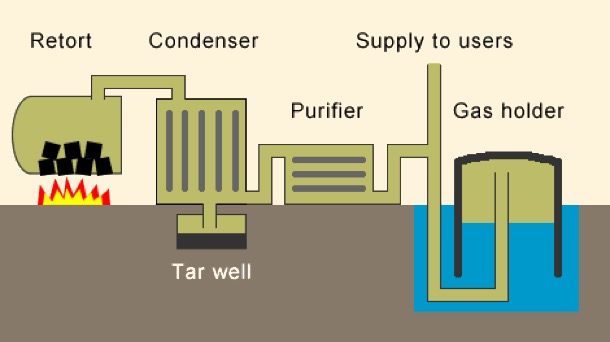

He worked in the laboratory, doing things like checking the calorific value of the gas.

Melbourne’s gas supply was made from Latrobe Valley brown coal, sent by rail to the various gasworks, owned by Colonial Gas Company. Box Hill was one of the biggest. As Melbourne expanded after the war, the demand for gas meant that the various gas works were very busy.

But, by 1960, substantial natural gas reserves had been discovered around Australia. Over the next five years all the Gas plants in Melbourne had closed down, and over 1000 workers were made redundant, by the discovery of natural gas deposit in Bass Strait. Over one million gas appliances in Melbourne were converted to natural gas in 1968. We remember the conversion time. There must have been plenty of publicity. Natural gas has no smell, and, for safety, they put in an additive to make it smell quite strongly. The flame was slightly different, but all the existing burners still worked.

The Gas Works are long gone. Box Hill Institute now occupies the site.

One of the fortnightly highlights in our simple lives was a trip to Box Hill Library. We loved this excursion, as we spent many hours reading on our beds. Books were expensive and we only owned a few. We had to rely on the Library so that we could finish our favourite series like Famous Five and the Billabong Books.It was very exciting if the next book in the series was on the shelf.

This small brick building was opposite the Town Hall at the end of the shopping centre. Whitehorse Road always had a wide, tree lined median strip, as it does today, and the library was right in the middle. It was later replaced by a grand modern library, but the small brick building is still there.

In our childhood, a trip to Box Hill shopping centre was quite an excursion, involving a four mile walk. In 2019 Google Maps says it takes thirty two minutes, but with small legs and a pusher as well, maybe it took a little longer. I remember it was fun and not arduous at all. The route went through suburban streets until Canterbury Road and from there it was ovals and open ground.

Box Hill Brickworks was one of the best sights on the walk to Box Hill, as the brickworks were still in full production. We marvelled at how small the men and carts were at the bottom of the quarry, and watched the procession of carts pass up and down the steep rail track to the actual brick works.

Box Hill Brickworks was founded in 1884 and was one of fifty or so brickworks throughout Melbourne, producing bricks, tiles and pipes for the building boom and ever expanding city. During the working life of the brickworks the clay was extracted from two clay holes or quarries. The first became Surrey Dive which became a popular swimming venue, but off limits to us. Sometimes however, we also gave ourselves the horrors, looking at green, mysterious waters. There were rumours of 'the dive' being bottomless and of swimmers disappearing in its murky depths. One story was of a man who took a very deep dive off the cliff side and simply disappeared. Some time later his body surfaced in Blackburn Lake, five kilometres away. No wonder we looked in awe and horror through the fence.

Today Surrey Dive is an attractive small urban lake used for swimming and remote controlled boat races.. A walking track around the ‘old dive’ and the brick works is planted with indigenous vegetation and a relaxing and attractive area.

The other clay hole was the quarry that was in operation doing our childhood. It was adjacent to the brickworks and kiln, now derelict but still heritage listed. Unfortunately no restoration work has been carried out. The kiln itself was a massive, red brick building constructed on two levels and, of course, with a huge brick chimney.

The quarry that was still in full production in our childhood, is now completely filled in. That cavernous hole in the ground is now a large mound covered in every weed known to man. On the horizon above the weeds, are the sky scrapers of twenty-first century Box Hill.

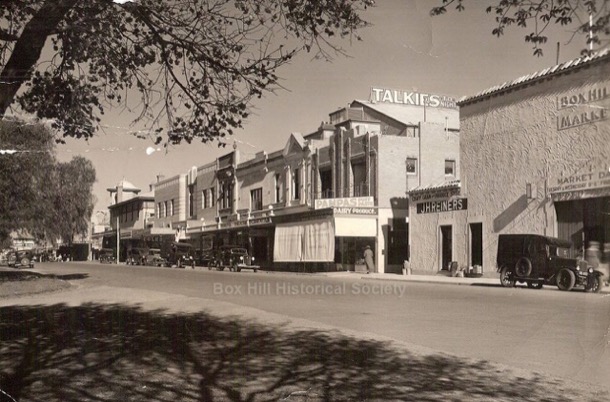

Box Hill shopping centre developed as a commercial centre, as soon as the railway line between Hawthorn and Lilydale was finished in 1862. It became an important transport hub for the eastern suburbs and beyond. During our childhood, Box Hill was the shopping destination for a big purchases. For instance, I can remember choosing a ‘walking’ doll with opening and closing eyes for a birthday present and the excitement of choosing a winter coat with a brown velvet collar. Another favourite shop was the delicatessen where such delicacies as rollmops, sauerkraut and frankfurters could be bought. Amongst the many single fronted small businesses were several large shops such as Taits haberdashery on the corner of Whitehorse Road and Station Street and Maples furniture shop. We also had a Coles variety store that sold anything from socks and singles to cosmetics, and MacEwans Hardware whose slogan was, “You can do it with McEwans because we’ve got a million things.”

This is a photograph of Box Hill Station and the surrounding shopping precinct in the 1960s. In the centre of the photograph is the old station, that is now underground. Today, above ground, occupying the whole block surrounding the old station, is Box Hill Central and surrounding shopping malls. The signal box, the tall structure on the left of the railway gates is now occupied by the thirty-six storey golden residential tower, called Sky-One.

In the twenty-first century, Box Hill, as a commercial centre and transport hub, continues to influence the built environment around it, as you have no doubt witnessed. Officially designated as a development hub, Box Hill now sports high rise office and apartment towers. The streets we once drove down are now shopping malls, the station is underground, the railway gates are long gone and the strip shops have been replaced by a multi storey modern shopping centre. When we were children the shopping crowds were white and Anglo-Saxon. Today they are predominately Asian and the shops and restaurants reflect the change in population.

When we, as a family, first started going to the local Presbyterian church, it was called Presbyterian, Wattle Park. We had PWP embroidered on the front of our blue gym uniforms. This was before the advent of the Uniting Church. Church services were held in a cream brick building, called Forsythe Hall.

Attached, behind it, was an older little wooden building. During our childhood, this wooden building, Staley Hall, was used for a kindergarten during weekdays. In the evenings, various groups used it, including church boys’ and girls’ clubs (PBA and PGA) and the mixed club (PFA- Presbyterian Fellowship Association), we went to as teenagers. Sue and I both learnt to dance there, and I broke my front teeth on the heater in that room.

We have many memories of Forsyth Hall… dances, performances, Saturday afternoon movies, gym classes and, of course church services.

Both our parents were Elders of the church. Our mother taught Sunday School, our father ran the PFA for a while, and was on the board of management. The church was their only real friendship group, and was the only social life we had, as a family.

In the early 1960s the church community began the project of building a new church on the site. The size and scale of the project was a source of much disagreement between our father and others on the management committee.

In the end, a very grand architect designed building was commissioned. The new building was designed by well known architects Chandler & Patrick. An 1887 pipe organ was relocated from a church in Melbourne and extensively rebuilt. The new church, renamed St James, opened in 1965.

I loved it, because I sang in the church choir, and it had a choir loft at the back and great acoustics.

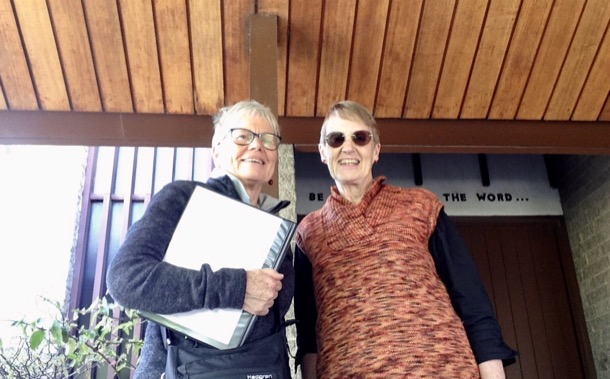

The buildings are still there. Sue and I visited as a detour on our “back to school” walk in 2016.