The Croydon Years

When the Coates family moved to Croydon it was the beginning of the Great Depression and many men were out of work. To complicate matters, Alf had been in partnership in a hardware business in Bacchus Marsh that had burnt down. Not only was the fire a personally traumatic experience for the family, as their house had also burnt down, but the business was not insured. As manager, Alf was responsible for the lack of insurance. He was therefore "lucky indeed" to have the job as the hardware store manager at the Croydon Timber Yard. He was on a reduced salary as recompense for the losses of the other Bacchus Marsh partners, who now owned the Croydon business.

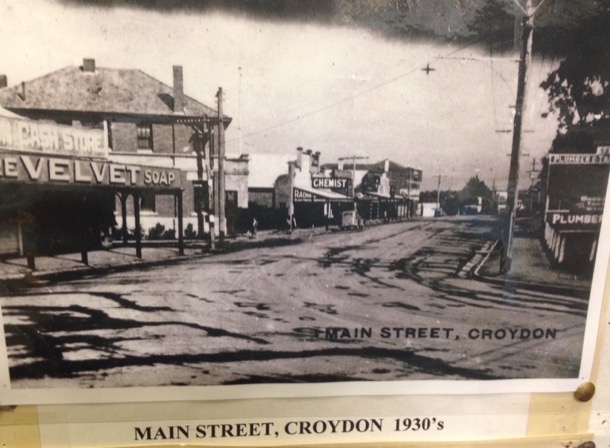

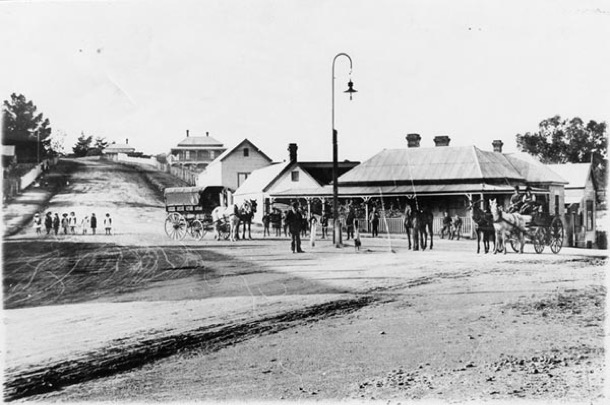

Croydon was at that time a pretty country town, connected to the world by the railway that ran, as it does now, from Flinders Street to Lilydale.

White settlement had reached Croydon in the 1850’s, as timber cutters arrived seeking new sources of timber for the needs of rapidly expanding Melbourne. Many small, and a few large land holdings were taken up, and fruit trees were found to flourish in the area.

The town that the Coates family found, spread out from the railway station. Businesses and shops were strung out along the long, wide, slightly curving main street. The Dandenong Ranges made a lovely backdrop to the town that was surrounded by small farms, orchards and bushland. Home for the Coates was a small house, painted battleship grey, in Hewish Road, very near the corner of Main Street. This was the wrong side of the tracks. The expensive houses were built over the railway line in Wicklow Avenue, extending up the hill towards what is now Maroondah Highway.

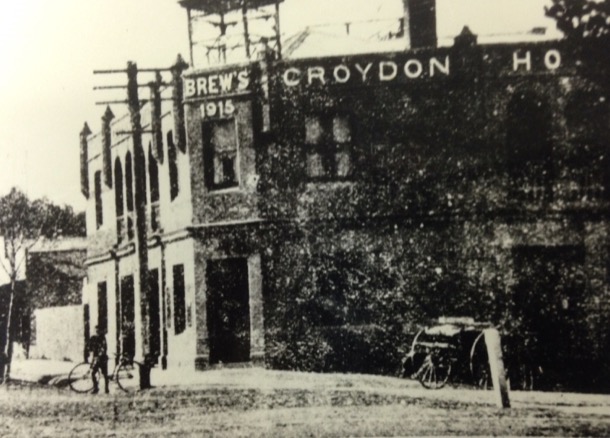

They remember their house as having a beautiful backyard, graced by an enormous Mulberry tree and a large vegetable garden. There was a cow paddock on one side of the house and the Wine Hall on the other. Hewish Road at that time was unmade, covered in hard stone embedded in the clay. The Coates were right in the business end of town: Cook’s Grain Store was directly opposite and Croydon Timber Yard, not far away, also in Hewish Road. Not only did this fiercely teetotal family live next to the Wine Hall located on Main Street corner, but on the other corner was the Croydon Hotel. These two establishments loom large in their childhood memories, as they were the source of the moaning drunken men that they sometimes heard outside. Occasionally their father had to take the men home.

Croydon Hotel:

Croydon Wine Hall:

Alf worked weekdays, Friday nights and Saturday mornings at the timber yard. Once a month he also drove the truck to the wharves to collect timber.

Money was tight, especially as Alf and Alfreda wanted their girls to have a decent secondary education at MacRobertson Girls' High School in Albert Park. One-third of Alf’s wage went on rent and by the time bills were paid and weekly expenses were covered, there was not much left over. At secondary school, fees were charged, books and uniforms would need to be purchased and weekly train fares paid for. Daily life therefore included the care of livestock and the processing of milk and eggs: all quite time consuming.

As well as their home grown vegetables and fresh eggs, the Coates family produced their own milk and cream.

All was not hard work however, and the Coates’ kitchen, warmed by the one-fire stove, was the venue for cups of tea and chats, many of them about cricket. In the picture, Alf is second from the top left:

Marge and Alice had a very happy childhood in Croydon. They played often with the Cook sisters, Yvonne and Margaret, who lived opposite. The Cooks had once owned the Croydon Timber Company, Alf’s employer.

Their house was on the other side of Hewish Road, next to the hotel. Connected to the Cook’s house was the grain store, which was now the core of Mr Cook’s business. There were delivery horses in a nearby stable too, and cows in the paddocks behind. The grain store was packed with bags of chaff and grain. The girls spent many hours playing in there, climbing right up to the roof.

One happy memory is of “penny concerts”. Hours of preparation: planning, costume making, and rehearsing, culminated in a concert performed on the Cook’s wide side verandah. This seemed to be mostly in the summer holidays, when the Cook girls’ cousins came to stay. Marge and Alice sang part songs, often Elizabethan madrigals they had learnt at school: Alice singing soprano and Marge, alto. The adult audience (probably only their parents) paid a penny to attend.

Alice remembered playing a sort of scavenger hunt, following written clues to find a prize. “Next clue under the camellia bush”.

She also remembered marbles, played in the dirt on the side of the unmade Hewish Road. When Sue and I stood on the same spot in our Croydon visit, we could hardly cross Hewish Road, for traffic! In the 1930s, it was a quiet gravel road with no gutters and unmade footpaths.

The Coates and Cooks lived opposite each other, and used to signal out of windows at night across Hewish Road. They planned, but never carried out, midnight feasts.

The wild games and excitement of playing with the Cook contrasted with the much more demure and restrained Hebbard girls. Pam and Honor Hebbard were the daughters of Frank Hebbard, the Primary School Principal, and friend of Alf and Freda. Their huge library of books were available for Marge and Alice to borrow, and the garden was a delight to play in. The Hebbards lived up on the Hill, at the top of Kent Avenue, which wound up to what is now the Maroondah Highway, through foothills bushland. A favourite activity with the Hebbards was to wander this bushland looking for native orchids. The remnants of this forest are much prized today, though much of it is degraded, and many of the species of orchid are now only to be seem in a museum.

Visits to the beach, during Marge and Alice’s Croydon years, were limited to School and Sunday School picnics. But they did learn to swim. They would go by train to Lilydale, where there was a huge concrete tank, right on the side of the Olinda Creek. Fresh water would flow in and out with this quite large perennial creek. Alice remembered Mr Hebbard lining them all up along the side and getting them to enter the water with a shallow dive. Nowadays the pool has become a more modern outdoor pool, but it’s still in much the same place.

Friday night shopping was another form of fun. Marge recalled it as a chance for everyone to parade up and down the street. Alice remembered buying “sixpennorth” of lollies and sharing them out. It was a simple life for these country kids. It is notable that, three years apart in age, much of their leisure time was spent playing together.

Marge and Alice of course went to Primary School during these years at Croydon, Marge as far as Grade 8. We will spend more time on this important topic at a later date. Suffice to say, at the moment, that their parents’ friend, Frank Hebbard was the Principal, and he ran a very enlightened, rich educational program, in which the girls flourished. The Croydon Primary School has new premises these days, but the old buildings are still there, now occupied by a Community School.

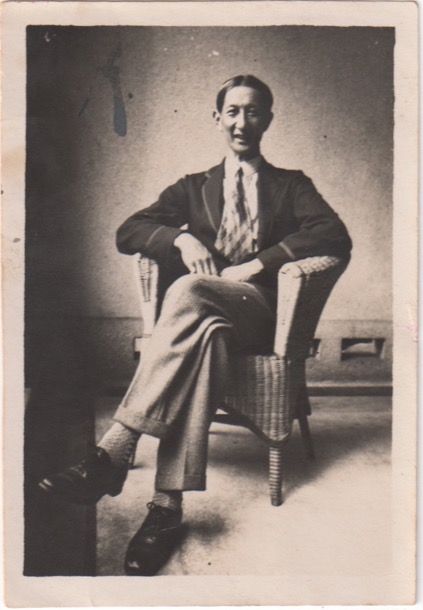

Family entertainment included hikes from Croydon to Kalorama, and visits to friends, the Cheongs. They were a wealthy and prominent family in the area. At our visit to the museum in Croydon we found many mentions of them, in particular their importance to conservation of remnant foothills vegetation. Even now Cheong Wildflower Reserve, near Croydon, still fulfils that role.

Mr Cheong, from our mother's photo collection:

In their leisure time, many happy hours were spent in the Coates’ warm kitchen, “yarning’.

Even though much of the good food the Coates family ate was home grown, some things had to be purchased at the Main Street shops.

The Croydon years were remembered very fondly by both Marge and Alice. They were formative years for both of them. Alice actually names the four areas of interest from those years that became her life long passions.

In 1936 the Croydon years came to an end with the death of Martha Holm, Alfreda’s mother. Presumably the family had to move back to Boronia Street, Surrey Hills to help Alfreda's sister, Berta take care of Roger Holm, now quite an elderly man. Berta was working full time at her dressmaking business. Alf found a new job in the city and Alice embarked on her secondary schooling at MacRobertson Girls’ High School.

The Demon Drink

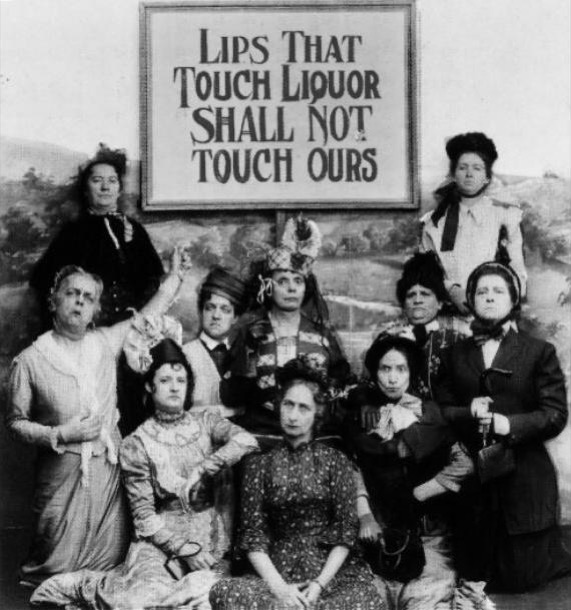

It was clearly uncommon for anyone in our narrow anglo world to drink at home. Here, for instance, is an extract from a Primary school resource book on Temperance from the 1950s.

The international Temperance movement was one of the most powerful social movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Its advocates regarded alcohol as a social evil and sought to have it banned entirely, or at least its consumption drastically reduced.

Initially it was just a move against drinking spirits and “hard liquor". But during Victorian times it became more a push for total abstinence and became more specifically a women’s movement, connected with Protestant Christianity. Groups of women activists were to be found right across the western world.

The Temperance movement had its most obvious success in America, where the sale of alcohol became illegal across the whole country overnight in 1920.

This period of American history has become known as ‘Prohibition”, the Roaring Twenties. It conjures up images of gangsters, speak easies and moonshine. The law did not have the support of much of the population. But it wasn’t until 1933 that it was finally repealed.

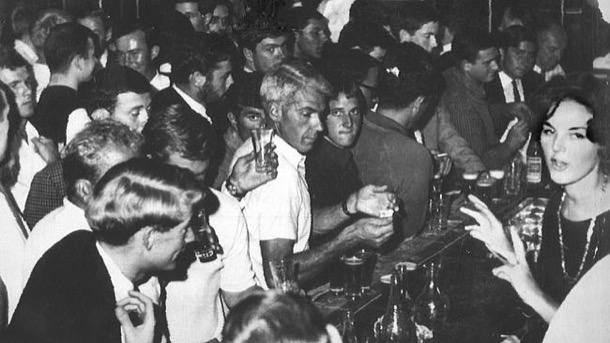

In Australia the temperance movement did not succeed in having the ‘demon drink’ banned but it did lobby vigorously for restriction of hotel opening hours. By 1923, hotel opening hours were restricted in all states. The closing of hotels at 6.00 PM led to a phenomenon known as the ‘Six O’clock Swill’.

It is hard to believe looking back that the daily rush to the bar was part of everyday life. Rather than limit drunkenness it actually encouraged it, as men who ‘knocked off’ work at 5 o’clock had only on hour in which to drink. Hotels were set up to serve as many beers as were demanded in this hour. Pubs were overcrowded, as men five or six deep lined the bar waiting to be served and patrons spilled out into the streets.

Pubs did smell strongly of beer as so much was served in such a short time. Sue can remember walking past Young and Jacksons on her way home and pushing her way through the throng of men, spilling out onto the pavement on the corner of Flinders Street and Swanston Street. Men, yes only men! Women were not permitted in the Bar until the early 1960s and for many years after that it was frowned upon. We can remember conversation stopping momentarily when we first walked into a bar, particularly in the country.

The Demon Drink indeed! We come from a long line of teetotallers: our great grandfather Reverent Alfred Coates, our great aunt Sister Bessie, our maternal grandparents, Alfred and Alfreda, their siblings and our parents. Our mother’s family, the Coates, being staunchly Methodist, we imagine would have been very sympathetic to the temperance agenda. Here is Alfred, in his Methodist pastor uniform with Emma and their daughter:

We were very aware as children that none of our family touched alcohol and that it was particularly frowned on by our rather upright Grandfather.

We too, at the tender age of eleven of twelve, have had our brush with The Independent Order of Rechabites, who provide educational material for Victorian Schools.

Alice and Marge as old ladies recounted their childhood memories of drunkenness, in the country town of Croydon during the 1930s, with obvious disapproval and distaste. Here they discuss the public drunkenness they witnessed at the hotel and wine hall near their house:

I remember our aunt having a glass of beer at the dinner table, when we were staying there as children. I commented on it and I remember being rebuked. Later our mother told me that it was medicinal, that she had found that drinking beer with food helped her digestion. That mum had felt the need to explain it that way, and that our aunt had reacted so strongly to a child’s interest is understandable in the light of heir own childhood experiences and family attitudes.

And then, during our late teens, as the 1960s became the 1970s, this part of our past just melted away. It became normal and natural too open a bottle of wine to share. There was binge drinking around us, especially at Uni parties, and the drink driving hazard was evident, but the moral dimension, the “holier than thou” attitudes, the raised eyebrow were all gone. Society had grown up about the same time that we did.

.

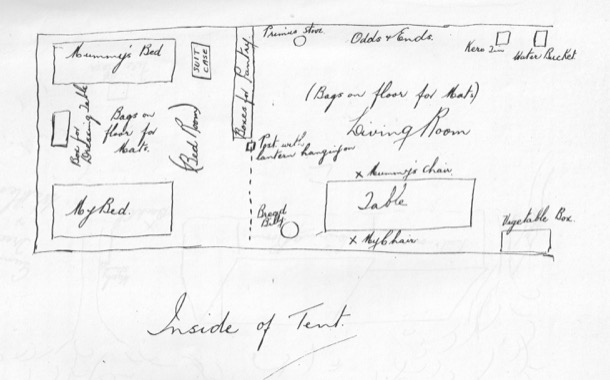

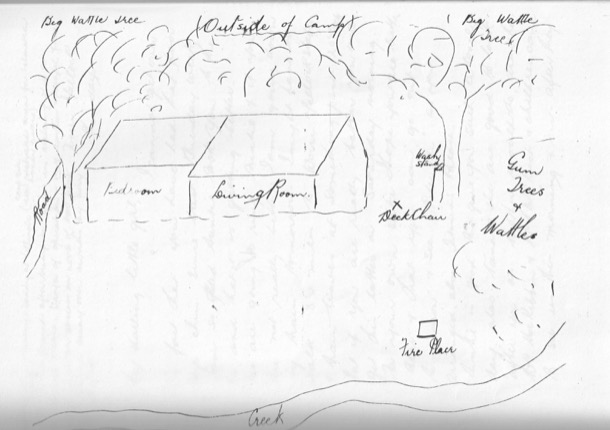

Family camping

Our grandparents and parents had camped as young adults, so living in third world conditions in order to be able to enjoy ‘the bush’ was not a new pastime in our family.

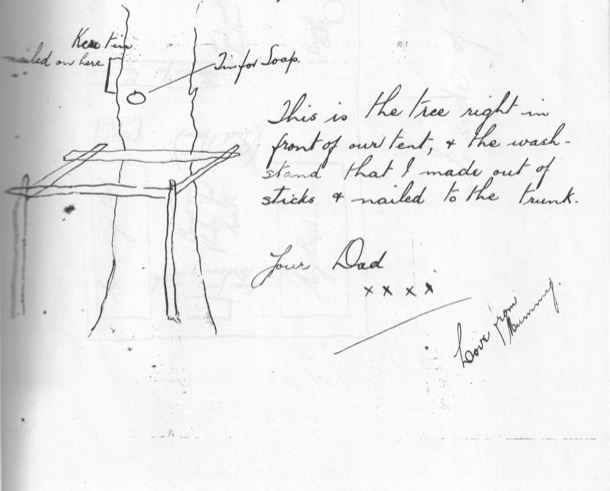

In January 1935, Alf and Alfreda, camping in the bush by the Yellingbow Creek in Woori Yallock, sent letters back to their daughters. In them Alf drew pictures of their camp:

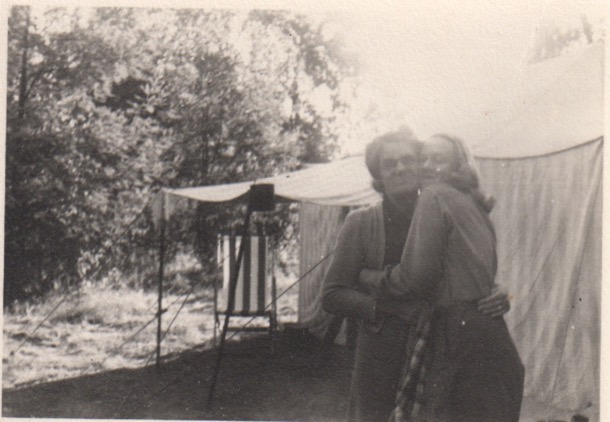

And Alice as an adult, camping with her parents:

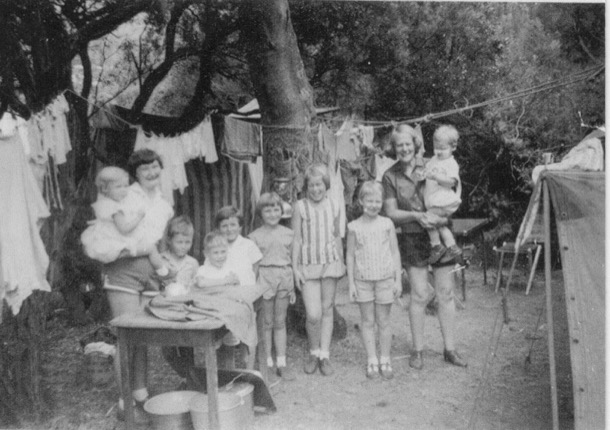

Our parents, Jim and Alice, went camping too:

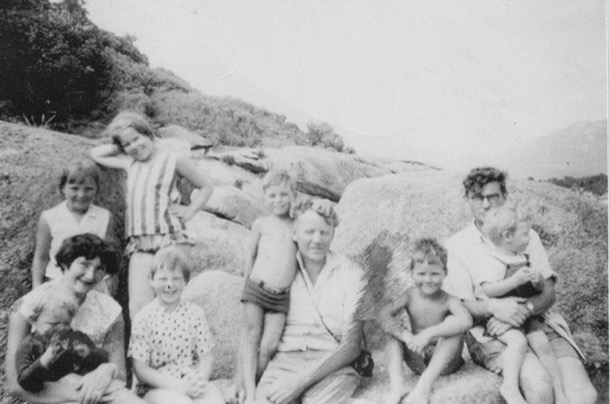

1958 and we kids embarked on our lifetime of camping. It was very exciting. We went to the Prom with the Lees, a family of five who lived at the end our street. We hired a big canvas tent, a simple square and most of the cooking was done outside. I remember this holiday vividly. We all had a wonderful time swimming in the river and the sea and walking. We even all made it to the top of Mt Oberon.

One memorable day there was much preparation for the ‘heat wave’ with temperatures over 100 degrees. Yes, fahrenheit, we are old! A picnic lunch was planned and we waded over the river with supplies for the day. The shady little beach on the other side was the perfect spot for a hot day but i am sure we all managed to get sunburnt. No sunscreen in those days!

That holiday must have been a great success as preparations were made the following year for Christmas holidays to be spent at a new place Mum and Dad had found with the Wilkinsons, a family from the Church. So began the long summer holiday tradition of going to Shoreham.

One of the important purchases that has remained in both our memories was the tent. As we were short of money our parents decided to buy an Army surplus tent. We went to Williamstown to pick it up. In those days driving to Williamstown involved a ride across the mouth of the Yarra on a punt that took a few cars at a time: so interesting that Margaret wrote a Grade 2 Composition on the very subject. Here it as as written:

‘On Sunday we went to hire a tent. It was a very long way. The place we hired the tent from was called Williamstown. On the way we saw many ships and boats. Also we saw a rubbish tip where our Australian rubbish is tiped. When we go there we pressed a button and a man came out. Then we went to buy some icy-poles. When we got back I asked Mummy what a man was doing, Mummy said he was drunk, I said ‘OOOOH’ He herd music playing and wanted to get in. He was knocking and waving then he touched his hat took it off and put it on a man’s knee. Then we had a ride on a queer ferry. which parted from the road.‘

It was a huge heavy old tent, khaki with big black letters and numbers stencilled on the roof. it was rather dark inside and it LEAKED.

Next year Dad’s Uncle Austin died intestate. As he was unmarried, his estate was divided between his relations. The law does not cut people from wills for marrying Protestants so Dad received his share. What a lucky windfall! It enabled us to buy a smart new tent that did not leak and was light and airy

Shoreham Foreshore Camping Ground was on a bushy small promontory on Western Port Bay. It was part of a sleepy small holiday place still surrounded by small farms. There were not a vineyard in sight. The camping sites were well spaced and some were quite secluded. The bookings were done through Mr Webb who was the Ranger and lived in a house abutting the camping area. Water was available in three large water tanks near our site. There were several toilet blocks where, in the morning, a small queue of brunch-coat clad ladies could be seen snaking its way up the hill. Pastel shades and floral prints were the predominant choice of fabric.

No showers though. Apart from swimming nearly everyday, a bath in the baby’s bath had to suffice.

Our tent was divided into three rooms: two for sleeping, equipped with double bunks, and a general living and kitchen space. We also had a flywire annexe where we had a camping table for meals. The floor, which covered the whole interior, was made from chook food bags we had sewn together on the back lawn. It became quite flat over the years and always smelt pleasantly of chook food pellets.

While Mum was sewing our summer shorts and tops, Dad used to come down a week early and set up camp. It was quite a trailer load and a big job as we had a big wooden chest of drawers, double bunks a two burner gas stove with a griller, chairs, table and an old ice chest. The iceman used to come to the camp ground so we could always keep food cold. In later years we moved onto a gas fridge. A week later we would descend with clothes, food, Christmas presents and a big wooden box of books all ready for a blissful six weeks of beach, shuttlecock, 500, reading and fun.

The book box was quite a feature and sat in the central living space. Dad raided the school library and we all borrowed the maximum from the Box Hill Library. We always had a wonderful collection to choose from. There were often a number of books in series such as A.J. Cronin's series on the life a young doctor in a Welsh mining village in the 1920s and many Who Dunnits. Great absorbing reads that we all looked forward to.

Another of the memorable, nightly rituals was the lighting of the Tilley. Tilleys are kerosene fuelled pressure lights that give out a tremendous amount of white light and therefore were terrific to read by. The lighting ritual was impressive to young eyes as it involved a flaming ‘thing’ that was clapped around the stem of the Tilley. Once the mantle was heated and glowing and the flame had subsided pumping began and we waited with bated breath until the mantle popped and was a light.

Dinner and washing up would be done and so nightly activities could begin. Often wrapped in rugs we settled down to reading or, more often than not, 500 tournaments. It was great fun.

One wet day game was for Ian and Margaret to embarrass our mother by pretending she was hitting us. We would howl and scream “Pleeeease don’t hit me Mummy! Oh no you’re hurting him!” You get the idea. She would be torn between laughter and horror. Tents have thin walls and we were surrounded by other camping families. Sue even remembers the game extending to shadow play on the tent walls at night. She remembers coming back from the toilets and seeing the acted out scenes of horrific violence. It’s a bit sobering now to consider that some of the “audience” in other tents may well have experienced that violence in their lives for real!

Shoreham has a rocky promontory, exposed at low tide. Then it was too shallow to swim, so we kids spent the time turning over rocks to see the creatures scuttle away, as we walked way out on the rocks. Quite a long way out was “the rock pool”. It was big enough and deep enough to swim in. There was a flat rock at one end which was the “diving board”. The pool was full of waving sea weed, tiny fish, sea horses, anemones. This gave it an exotic, scary atmosphere. Jumping off the diving board and seeing how far we could swim underwater was a favourite game there.

The rocks seemed the same every tide. Year after year we kids clambered roughly over them, caught crabs, and sea urchins, took interesting creatures back to the tent, collected shells.

Sometime over the decades, Shoreham’s bio diversity diminished. There are still crabs, and a few anemones, but the sea horses and sparkly fish are gone.

One year, Ian, aged perhaps seven or eight, turning over one of those rocks, dropped it on his finger. There was lots of blood, huge drama, and a trip to the doctor in Hastings to have it stitched. Sue remembers she and I walking him back to the campground, each of us with an arm around him and Sue with her palm outstretched underneath the finger. She was sure it was about to drop off. I remember feeling very sorry for him because he was not allowed to go in the water for the whole rest of the summer.

Low tide exposed enough flat wet sand for French Cricket. This was organised by the fathers. Everyone played, but we girls really only tolerated it and weren’t very good.

Dad, Ian, Chris and a couple of Wilkinsons:

The worst thing about low tide was the sea grass. There were crabs scuttling through its waving fronds and if you swam over it, instead of risking your toes, eventually you felt it on your bare legs and arms and you simply had to stand up.

At high tide Shoreham had wonderful swimming. We would stay in for hours with our poor mother sitting on the beach keeping watch. Sometimes you had to share the water with drifts of dead sea grass, which would pile up in smelly cliffs as the tide went down again.

When our parents could be bothered taking us, we would walk around to the surf beach at Point Leo. Here we could body surf and jump around in the big waves. Later we even had a couple of blow up rubber “boards, like a small lilo with handles. The price you paid for playing in the surf was having to walk back with your bathers full of wet sand. I remember fearing that the wad of sand must have looked as if I’d pooed my pants.

Shoreham beach looking towards Point Leo:

In the other direction was Flinders and the ocean. The view of Flinders from Shoreham was of a long promontory. The Naval Base there used to have gunnery practice, evident to us by puffs of smoke and a distant “whomp whomp”.

Flinders in the far distance:

Weekdays involved walking to “the store”. Shoreham had a general store on the edge of the foreshore reserve. Dad and the four kids would walk up along the track, buy The Age, milk and whatever else was needed, even a Drumstick sometimes:

Then we would head along the main road to the Post Office. We took it in turns to go in and ask for “Any letters for Bourke?”. Then we would walk down the post office road to the beach track. Some days we would continue to follow the road past some holidays houses and then rejoin the campground track, but most often we would climb down the steps alongside “Camel’s Hump” and back along the beach. In my memory these steps were steep, treacherous and dangerously slippery. Back at camp Mum would be doing piles of holiday washing all by hand, after lugging the water from the tank and heating it up on the gas stove.

Most years, for one day, usually when it was not beach weather, we would pack a lunch and “walk to Flinders”. Mostly we walked both ways along the beach, making the Flinders pier the turnaround point, but sometimes we came back by the road, and bought fish and chips at the Flinders shop. It was an eight mile round trip, (about thirteen kilometres). The beach between Shoreham and Flinders, mostly deserted and wild, had a succession of small coves and rocky headlands. The first headland, covered in pine trees, separated the camp beach from “Shoreham Proper”.

Walking any distance along the beach included shell collecting. There were lots of interesting and colourful shells but the most prized were the cowries. It was not uncommon for each of us four kids to have twenty in our collection by the end of the summer holiday. We would also collect sea urchins, trapped in amongst the piles of dead sea grass.

I never understood the pleasures of sun baking, but would spend hours in the water. Our noses were zinc creamed, but not our shoulders. It must have been hard for our mother who was responsible for managing four children’s sun exposure. We were often sunburnt and sometimes even had blisters.

Sue and Mum in the sand dunes:

On the six or seven Sundays we were at Shoreham we would dress in the “good” clothes we had brought especially, and shoes (the rest of the time we wore thongs or sandals), and drive to Flinders Presbyterian Church. The Wilkinson family came too. Sue remembers the prickly feeling of a dress on sunburnt back and the resentment of having to go. The church was small and dark and had a small regular congregation. Afterwards we would pile back into the car and race back to the beach.

As the years went on and we went to Shoreham every summer, it became the way I measured the passing years. It was a benchmarking time. The tent set up, the beach, the bush all stayed the same. The people changed gradually, inexorably. Summer holidays was the time to recognise and celebrate this.

This clearly happened for the adults as well. I can remember Alan Wilkinson, chatting to our mother, oblivious of nearby children, the way adults were in those days. “I’m turning forty this year, Al. It’s hard, life’s passing me by.”

By the time I was fourteen I was spending Saturday nights during the year at local church dances. I don’t remember how it came about, but I remember going that summer to a surfer dance at Point Leo Surf Club. This was the time of Little Pattie and Col Joy. Wonderful music in my opinion. I remember a hot, dusty room full of blond suntanned kids, all moving in sync to a band playing covers. The surfy dance was ridiculously simple:

There were always more boys than girls at Shoreham over the summer. Only boys actually surfed. I remember a “date” with a boy who had a car. It was mortifying at first, when my mother insisted that Sue came with us because I was too young, and probably mortifying for her to have to be the chaperone, but I don’t remember where we went, so it can’t have been too bad.

Sue also had romantic episodes at Shoreham. One year she met a fellow camper, who was a Year 12 student doing a navy cadetship. She spent time in Melbourne that summer holidays, doing a “life drawing” course and went out with him over that summer:

Around the same time Dad and I were involved in a prank at the YMCA camp. Over the summer holidays there were crowds of young boys with older teenagers as camp leaders. I guess Dad might have got talking with the adults at the camp and hatched the plan.

Would I like to be involved? What, you mean walk alone into a room full of a hundred boys having dinner, find the mark, the shyest of the leaders, who has never seen me before, sidle up to him and put my head on his shoulder and snuggle up to him? Try and stop me!

After a few minutes, Dad appeared at the back of the room, brandishing a gun (!) “Where’s my daughter?” he howled.

I don’t remember what happened next, but I have a strong impression of being the only girl surrounded by a crowd of boys and loving it!

Our earlier experience of the YMCA camp was attending the outdoor “pictures”. Campers, each carrying a folding chair, would head off after dinner to the camp and set up facing the strung up bed sheet, amongst all the camp boys.

Shoreham camp was a social place for the adults as well. The same families would camp in the same sites each year, including a few we knew from our real lives. I remember late afternoons on the beach sitting in a group of Bourkes and Wilkinsons, ten kids between us, reluctant to break the spell of the setting sun and then going back to our tent and cooking dinner for fourteen. We had day visitors too, family and friends. I remember Mrs Moss, also a church friend of Mum’s, enormous and perfumed. I remember being impressed after I had complimented her on her dress, when she demurred and pointed out that she didn’t have “her corsets” on.

When the holidays ended we were brown as berries. Packing up was done and then home to the strange sensation of hard floors under our feet and the new school year.

War Service

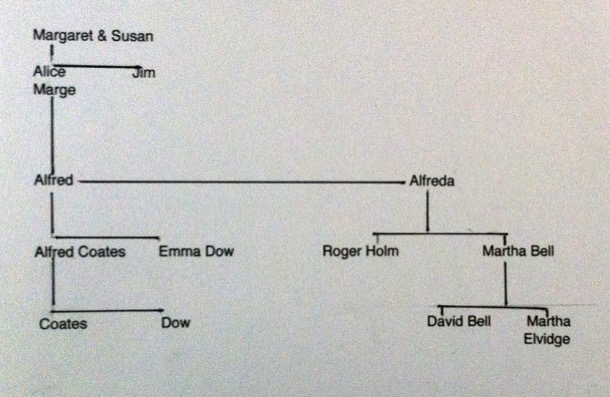

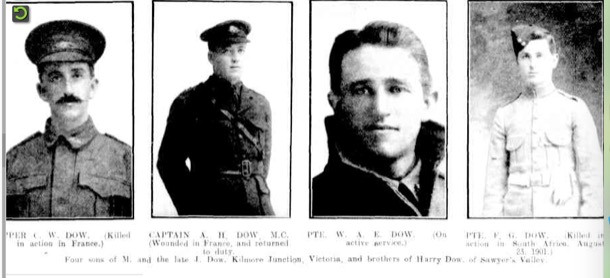

Our family stories research has led to the discovery of four great great uncles: four brothers who were soldiers. They were four of the seventeen children of Martha and Joachim of Heather Farm in Wandong, about whom we wrote in "The Poor Little Thing" on June 8th, 2016 and "Heather Farm" on August 3rd, 2016. Our maternal grandfather Alf, was their nephew.

Learning their stories, imagining their experiences, fitting their details into the wider sweeps of military history has been enthralling and rewarding.

We present the four Dau (Dow) brothers, Frederick, Arthur, Charles and Walter.

Frederick and Arthur actually enlisted as Dow, an anglicised version of Dau. It is a constant confusion.

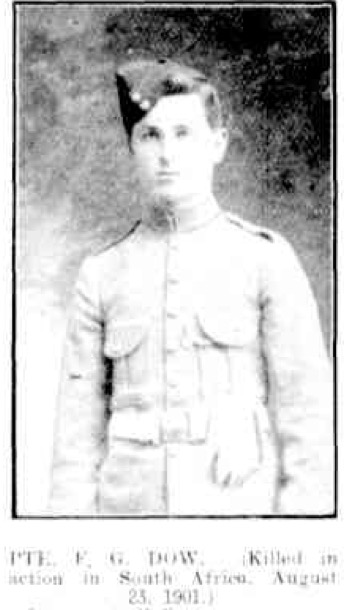

PRIVATE F. G. DOW

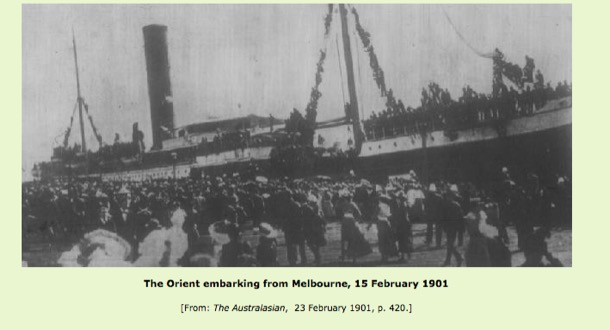

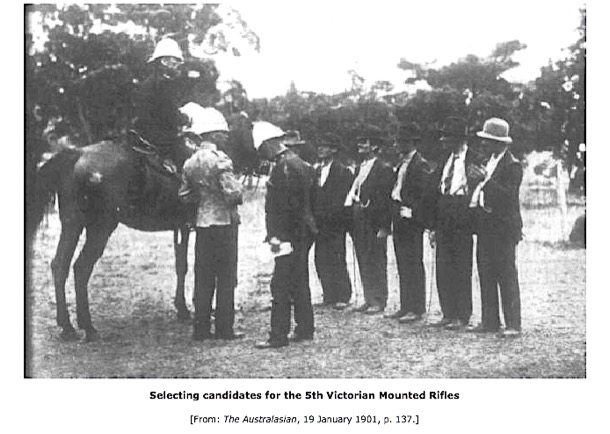

Australia was twenty-eight days old when nineteen year old Frederick sailed on The Orient out of Melbourne, bound for South Africa and the Boer War. His company was the Fifth Victorian Mounted Rifles.

Britain had colonised the southern part of South Africa eighty years earlier and had had an uneasy relationship with the other colonisers of this area, the Dutch Boers, who had been there for a hundred and fifty years longer. Tensions had escalated to war in 1899, and the British Empire was required to send troops to participate.

By 1901, the war had become a drawn out guerrilla affair mostly in the desert-like Transvaal area with small groups of Boer soldiers attacking and then disappearing back into the harsh dry landscape.

Many of the “colonial” troops, like Frederick were bushmen, tough, self reliant and skilled at shooting from horseback: exactly the set of skills needed for this type of warfare. But it was very hard on men and horses alike. Most of the fighting took the form of small skirmishes, but sometimes the men had to attack remote farmhouses, confiscate the livestock, destroy the farms and escort the women and children to the notorious concentration camps where thousands died. R G Keys of South Moorabbin wrote of making captures of large numbers of prisoners and cattle and having brought in large numbers of Boer families. “We have also burnt thousands of acres of grass and a number of farms and have destroyed everything of any use to the Boers.”

They spent long periods in the saddle with few opportunities to bathe or change their clothes; lice were a constant problem. Temperatures on the veld ranged from relentless heat during the day to freezing cold at night.

Private F W Collins wrote, “What I can see of the war is that the Boers can keep it on as long as they like, the only way is to starve them out. They get right in the mountains, and there are bullets whizzing about you and you cannot see any enemy. We are going from daylight till dark, up at 4 o’clock in the morning, and it is sometimes midnight before we get in again, so you can imagine we feel quite knocked out. When I get back to old Victoria I’ll do nothing but sleep.”

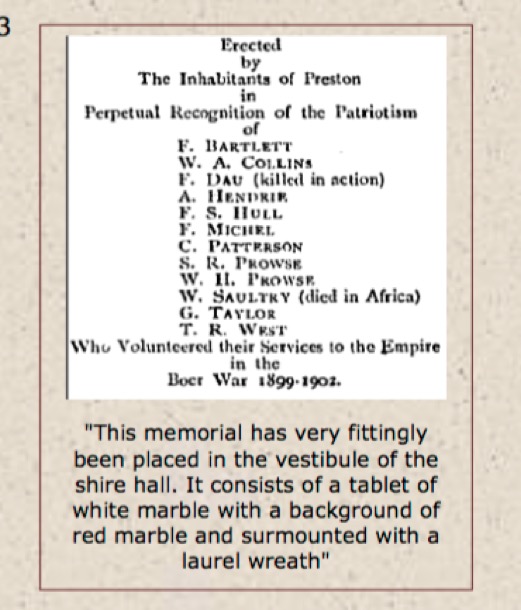

We don’t have much detail about Frederick’s death, but Lord Kitchener, Field Marshall in charge of the war, reported in one of his dispatches: "on the 23rd August Lieutenant Colonel Pulteney had a sharp engagement with the enemy on the west side of the Schurveberg, in which the Victorian MR (Mounted Rifles) had 2 men killed and 5 wounded.” One of those two men killed was Frederick Dow.

Two years later, his mother, Martha, and brother Harry inserted this memorial in the local paper:

In loving memory of dear Fred, who was killed in battle near Vryheld, South Africa, August 23, 1901; aged 19 years and 6 months.

Tis two sad years ago today,

The trial was hard, the shock severe,

To part with one we loved so dear.

He is gone, but not forgotten,

Never shall his memory fade;

Sweetest thought shall ever linger

Round about our soldier’s grave.

MAJOR A. H. DOW

Arthur was on one of the first ships to leave Melbourne for the war. He sailed from Station Pier Melbourne on the Orvieto on October 21st 1914. There were huge crowds to wave off this first wave of volunteers.

Soldiers from the Orvieto disembarking at Egypt:

Arthur was a career soldier. He had joined up as a military engineer, aged seventeen in 1908 and had already been promoted to Warrant Officer.

Like all of those first soldiers, after a short time in Egypt, Arthur was dispatched as part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force to what would become known as Anzac Cove, Gallipoli. He was there for the very first Anzac Day landing, but went ashore “several days” later. He must have watched from his ship as the first few waves of shore boats struggled amid Turkish bullets and shells that rained down from the cliffs. By the time it was his turn, things were still very chaotic and dangerous. It took ten days for the troops to be safely dug in.

On June 16th, he was Injured and was treated at the hospital on the Greek island of Lemnos.

He went back to Gallipoli ten days later.

At the beginning of August, Arthur was detached for duty to Assistant Adjutant General 3rd Echelon in Alexandria (which dealt wth military discipline, though he was in the “records section&rdquo![]() .

.

By March 1916 he was with the Fourth division engineers at the huge Anzac training area near Cairo, called Tel-el-Kebir, a six mile long “tent city”, where he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant.

He must have participated in the notorious three day march across the desert in searing heat to Serapeum, on the Suez Canal.

Here there was more training, in preparation for the move to France, and he was promoted again to Lieutenant. On June 2nd, he travelled on the ship “Kinsfaun Castle” to Marseilles, in the south of France.

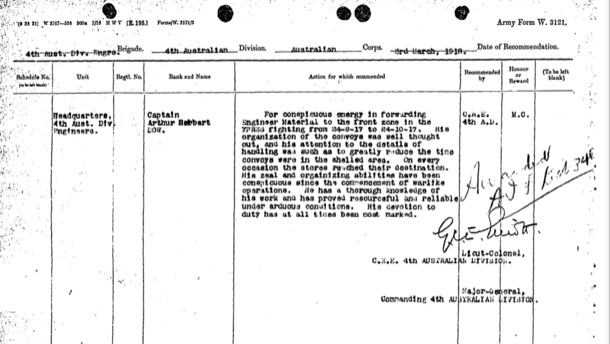

The next mention in Arthur’s record is six months later, in January 1917, where he is “mentioned in despatches” (a sort of honour) and then again on June 26th, where he is promoted to Captain.

We know what he was involved in during those couple of years in France and Belgium because we know what unit he was in.

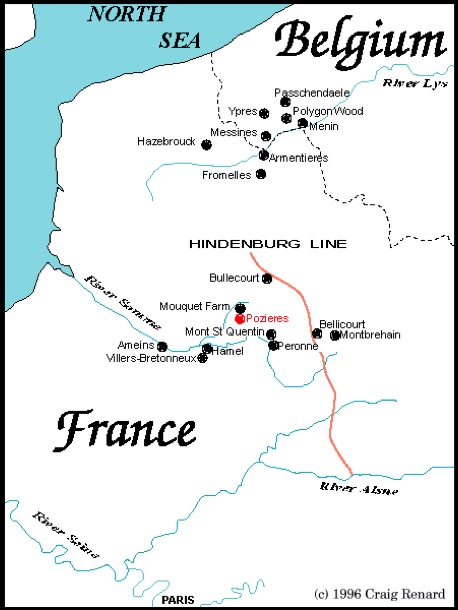

He fought at Ypres and Messines Ridge and Passchendael: all infamous places in the history of the first world war.

It was for his work from 24th September through to 24th October that he was awarded the Military Cross.

Arthur was a military engineer. Engineers, also known as sappers, were essential to the running of the war. Without them, other branches of the Allied Forces would have found it difficult to cross the muddy and shell-ravaged ground of the Western Front. Their responsibilities included constructing the lines of defence, temporary bridges, tunnels and trenches, observation posts, roads, railways, communication lines, buildings of all kinds, showers and bathing facilities, and other material and mechanical solutions to the problems associated with fighting.

At the time Arthur won the Military Cross, the 4th Division was involved in the battle of Polygon Wood and then the third battle of Ypres, Passchendaele. It is from the Ypres-Passchendaele area that we get the iconic images we have of trench warfare in a landscape of deep mud and water filled shell holes with broken off toothpick trees, stretching away into a hazy distance; where falling off the duck board paths meant drowning in mud. By the time Passchendael was captured in November 1917, the Australians had fought for eight weeks and suffered over 38 thousand casualties.

At the beginning of December Arthur had a fortnight’s leave in Nice, Italy and on his return he was sent to England to Brightlingsea to train engineers. It must have been a welcome break, but he was back in France by May, 1918.

He was wounded in action on August 8th. At that time his company, the 14th Field Company Engineers was laying wire barriers across the area to be advanced upon in front of the village of Villers Brettoneux. They were harassed by constant German shellfire, and snipers.

The resulting battle was called the Battle for Amiens, and was a resounding success, although between August 7th and 14th, the Australians lost six and a half thousand men.

Arthur left for Australia on September 27th, and within six weeks the war was over.

He remained in the services for a few years. In 1920 he had a few months’ successful treatment for “depression and irritability”. On his application form, where he had to provide supporting evidence for his entitlement to this help, he wrote a single word: “Anzac”.

By 1940, one year into the second world war, Arthur, who had been working in a Government desk job in the civil service, rejoined the army as a Major. He was 49, married with two children, and living in St Kilda.

His war this time, was fought at a desk, sometimes in the Middle East and sometimes back in Australia. His war record mentions positions like “Hiring and Claims”, “Accomodation and Quartering”. He left finally in October 1945, aged 54. During this time he had treatment for an affected patch of skin in his mouth. The doctor mentions that this is the spot where Arthur’s pipe customarily sits.

The last mention of Arthur in the war record is application for repatriation consideration for a minor health issue. He was a healthy 72 and living in Boronia.

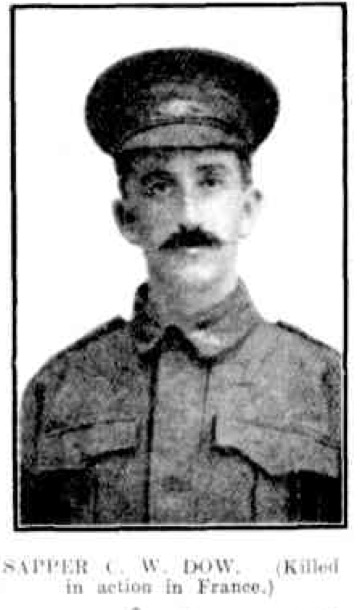

SAPPER C.W. DAU (DOW)

Like his brother Arthur, Charles enlisted as a sapper, or military engineer. He joined up in February 1916 in Hamilton, where he had been working as a railway “ganger”. He was thirty, slim, fair haired and blue eyed and was married to Edith, who was still back in Wandong with their three children.

He left for Europe in April and by October had joined the Second Division in Belgium, before marching to the Somme area in France. His division was involved in attacks on a collection of German trenches known as The Maze,

The main Somme fighting came to an end on 18 November in the rain, mud, and slush of the oncoming winter.

Over the next months, winter trench duty with its shelling and raids became almost unendurable and only improved a bit when the mud froze hard. The wet and the cold made life wretched. Respiratory diseases, “trench foot” – caused by prolonged standing in water – rheumatism and frost-bite were common. Many survivors would later say that this was the worst period of the war and that their spirits were never lower. Large-scale fighting did not resume until early 1917 when spring approached and a German offensive re-took areas previously heavily fought for.

Charles remained with the sixth field company, second division throughout. By the middle of 1917, they were in action in the mud at Passchendaelle. Charles’ brother Arthur was there too, with a different division. Eight weeks of heavy fighting took a huge toll on Australian troops.

At the end of 1917, he had a three week leave in England, returning to his unit in December, just in time for the German Spring Offensive, aimed at retaking Ypres in Flanders. The second division were involved in Messiness until March and then the battle of Lys in April. In June they participated in the very successful Battle of Hamel.

The Allies finally began to push the Germans back. Charles was involved in the Battle of Amiens and other attacks from the village of Villers-Bretonneux.

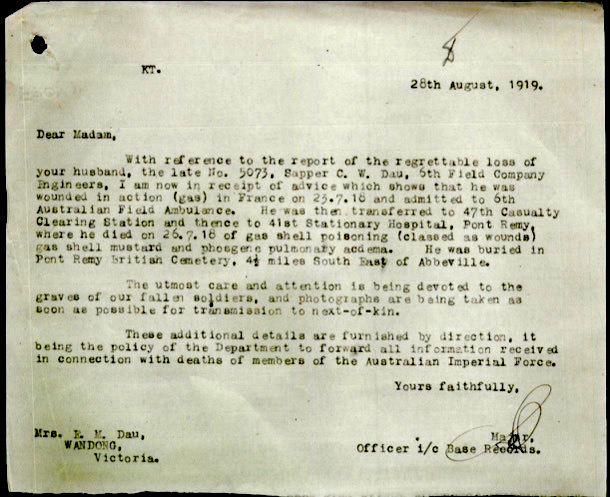

Then, on July 23rd, after weeks of very heavy fighting, Charles was affected by a mustard gas shell.

A letter to his wife, Edith, written in August the following year explains the story from here:

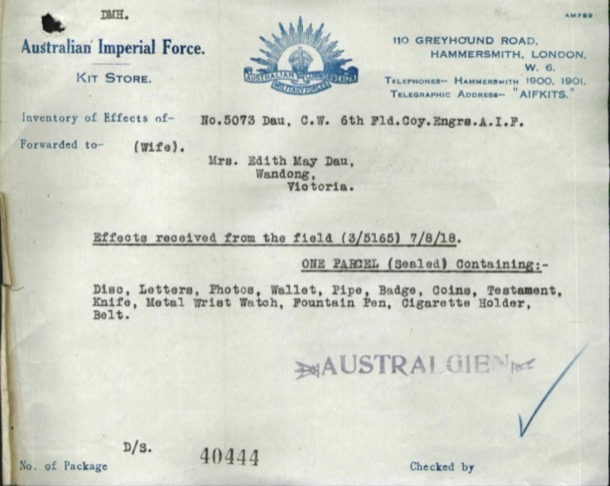

Edith received a parcel containing Charles' last few possessions:

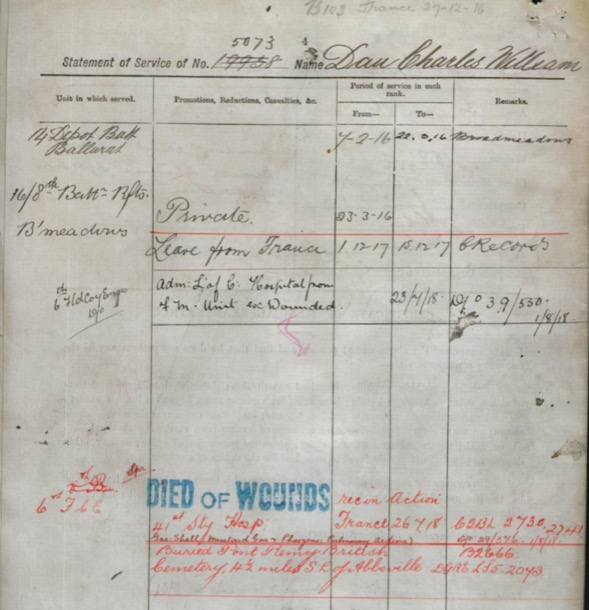

From Charles' military record:

Mustard Gas

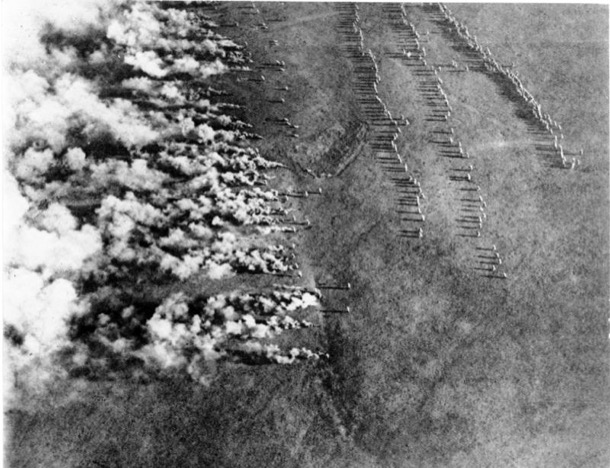

Chemical weapons were first used in World War I. They were primarily used to demoralize, injure, and kill soldiers in trenches, against whom the indiscriminate and generally very slow-moving or static nature of gas clouds would be most effective.

Some gases used actually killed soldiers, but mustard gas was more a disabling chemical. On initial exposure, victims didn’t notice much except for an oily or “mustard” smell, and so the first men exposed to this “mustard gas” did not even don their gasmasks. Only after a few hours did exposed skin began to blister, as the vocal cords became raw and the lungs filled with liquid.

Even if they did have their masks on, they developed terrible blisters all over the body as the gas soaked into their woollen uniforms. Contaminated uniforms had to be stripped off as fast as possible and washed - not exactly easy for men under attack on the front line.

Affected soldiers died or were rendered medically unfit for months, and often succumbed years or decades later to lung disease.

As the war went on both sides used various protective masks, and gas became less effective as an actual weapon, though its psychological power was enormous and both sides continued to use it . By 1918, one-third of all shells being used in World War I were filled with poison gas.

One nurse, wrote in her autobiography, "I wish those people who talk about going on with this war whatever it costs could see the soldiers suffering from mustard gas poisoning. Great mustard-coloured blisters, blind eyes, all sticky and stuck together, always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke."

PRIVATE W.A.E. DAU (DOW)

Walter Albert Edward Dau the third youngest and according to Marge and Alice ‘the black sheep of the family’ enlisted in the AIF in November !916. Wally’s medical record describes him as having fair hair and blue eyes. He was twenty-seven, unmarried and a motor driver by occupation. He sailed for England in March 1917 with reinforcements for the 21st Infantry Battalion and he returned to Australia in October 1922, where he was discharged from the Army in December of that year. On the tapes Marge and Alice recall that he was apparently a bit bookish and lived ‘as a bit of a hermit in Noogee.’ He died in 1974 maybe in Queensland.

Wally arrived in England and was initially based at Rollerstone a huge Army camp on the Salisbury plain. New arrivals were sent here and the placed in other training camps nearby. Between stints in hospital, Wally was assigned to the 6th Signals Battalion and then after a final few months at Grantham Military Hospital was trained as a machine gunner. Wally spent almost sixteen months moving between training facilities and several military hospitals.

The handwritten records mention Synovitis a painful, chronic inflammation of the joints, a ganglion on his arm and ‘Hysteria NYD’ [Not Yet Diagnosed]. While Wally was undergoing one of his hospital stays, his brother Charles was gassed and died in France. Finally in October 1918 Wally was transferred to the Machine Gun Corps, 21st Battalion and he was on track to go to France. Fate intervened and Wally sailed to France on the 28th of November, seventeen days after the war ended.

It is difficult to know why Wally was so long in England, but one month after Armistice, Wally was in France with the AIF Graves Unit. The Commonwealth Graves Commission had already been established in response to the public's reaction to the enormous losses in the war. Their work in France was to ensure that the final resting places of the dead would not be lost forever.

From the very first battles in the early weeks of the fighting on The Western Front, the number of military dead was already in the tens of thousands. Graves and burial grounds situated in the area of a battlefront were often damaged by subsequent fighting across the same location, resulting in the loss of the original marked graves.

Some bodies simply could not be retrieved from underground.

Added to this, the technical developments in the weaponry used by all sides frequently caused such dreadful injuries that it was not possible to identify or even find a complete body for burial.These factors were generally responsible for the high number of “missing” casualties on all sides and for the many thousands of graves for which the identity is described as “Unknown”. The AIF War Graves Unit was responsible for the cataloguing of the dead and the construction of the monuments and cemeteries.

One wonders what Wally's reaction was to this overwhelming task.

Wally, however found distractions. He had a daughter!

Amongst his military records is a translation of a letter written in 1933. The letter is from Madame Thomasson of Avignon France.

‘Please inform me where to write to Walter Dau, Australian subject’ involved in “War Grave Construction work in Belgium, who sailed from England to Australia in 1922. I should be very much obliged if you would supply me with information as to the whereabouts of this person who is the father of my daughter, ……. in order to define her position and nationality.’

The letter may never have reached Wally as it was passed between the Defence Department and Australia House, London with no record of delivery or response.

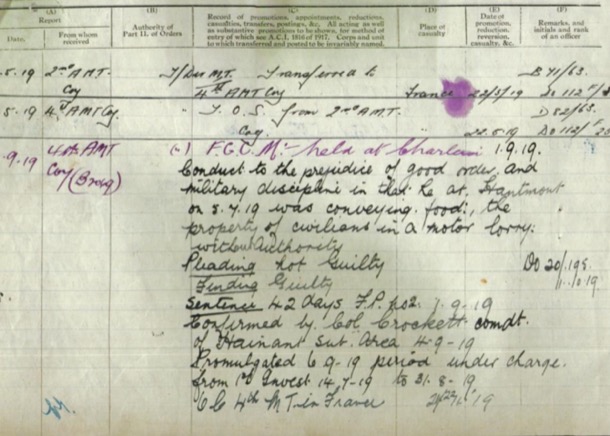

Another distraction for young Wally was 42 days of incarceration after he was Court-martialled for: ‘Conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline in that he ……was carrying food, the property of civilians a motor lorry, without authority’

Wally pleaded Not Guilty but the charge was upheld.

An interesting young man, many unanswered questions and a very different story to that of his two brothers who were in France during the fighting.

Alf and Alfreda: the Early Years

Alfreda, our maternal grandmother was living in St Kilda and attending the Melbourne Continuation School in the early 1900s. While she was finishing her secondary education. Alfreda met her future husband Alf, who was recovering from rheumatic fever and had left his country teaching position and moved to Melbourne to work at Blocky Stone, a hardware supply company. Alf boarded In St Kilda with his aunt Mishy Cowden. Arthur, Alf’s older brother had also boarded there and Arthur had an attractive young girlfriend, Alfreda Holm; not for long! Alfreda must have been quite attracted to this tall red headed young gentleman from the country. She abandoned Arthur, and Alf and Alfreda became ‘sweet hearts’ when she was 16 and he 17.

Alfreda completed the secondary schooling she had so desired. Even though she could have sat for the University entrance exam, her family could not support a full time student. Teaching was her only option. At the age of 18, she embarked on her teaching career at Elsternwick Primary School.

Elsternwick Primary School

Alfreda’s and Alf’s courtship was, as was the custom, a very proper affair and one would imagine that this was so, as Alf was the son of a pastor. Outings included picnics on the St Kilda Foreshore:

and ‘doing the block ‘ at the Block Arcade in Collins Street:

Collins Street

Alfreda pictured in 1910.

As Alf played cricket most Saturdays during the cricket season, Alfreda would have accompanied him; in fact she became so involved that she was appointed scorer.

Outings further afield involved visits to Alf’s family at Diamond Creek where Alf’s father was the Pastor at the Methodist Church. In the early 1900’s this was really the country and Alfreda enjoyed these visits and her introduction to country life.

Diamond Creek around 1910

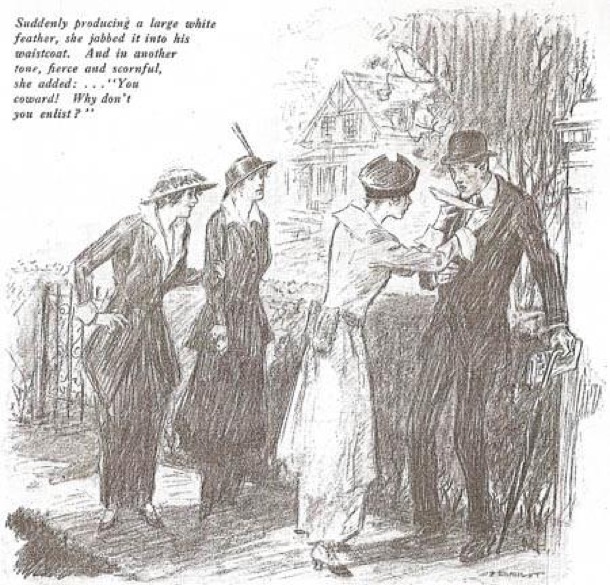

War in Europe broke out in 1914. Droves of young Australian men were enlisting in the army, hoping that it would last long enough for them to get there and have the great adventure it promised to be. A wave of fervent nationalism swept the country. Alf had recovered from the rheumatic fever that had ended his teaching career, but the residual heart damage meant that he was rejected for military service. A young man not in uniform, he was given a “white feather” as a mark of cowardice.

He suffered what was called a “nervous breakdown" which, at the time, was attributed to embarrassment and shame.

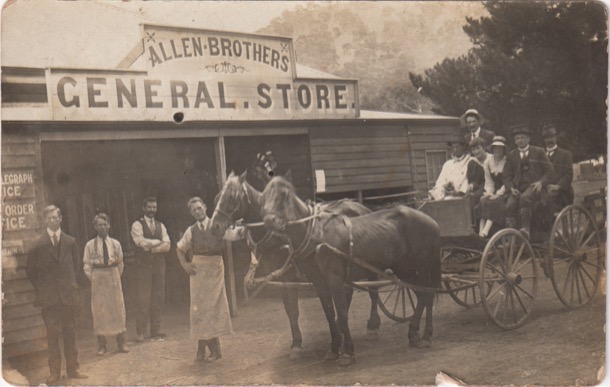

During his recovery, he lived in the small town of Eildon Weir, 140 kilometres away, where he managed the general store, selling supplies to the men building the weir.

Alfreda remained loyal to Alf first through his illness, which today we would call clinical depression, and then through his extended absence at Eildon Weir.

Later in 1914 Alfreda’s family moved to Surrey Hills, and Alf moved with them. Alfreda got a job teaching at Balwyn Primary School and Alf went back to his city job. They lived at Elwood Street Surrey Hills. Alf told the story of walking with a lantern down Florence Road in the early morning to catch the train at Surrey Hills station.

Alf and Alfreda were married on December 27th, 1916, at the Surrey Hills Methodist Church, which is still there today:

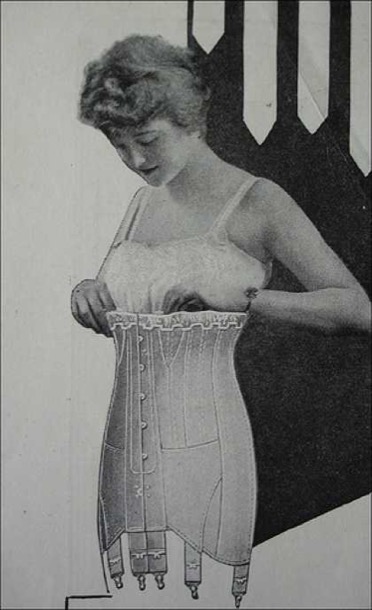

Alfreda did not dress as a bride. Marge tells us in the tapes that this was because it was war time, but a quick search shows plenty of women in full bridal regalia from that time. Perhaps they were super sensitive to how it would look, given that Alf was not “in uniform”. In any case, she wore a cream silk suit. She may well have had it made in the new fashion of flared skirts:

And underneath she would have worn a body moulding corset. Bras, which supported rather than moulded, were in their infancy at this time. They were patented in 1914.

The couple honeymooned at Ocean Grove. There was a steam train all the way to Queenscliff at the most southerly part of the Bellarine Peninsular. And then there would have been a bus to Ocean Grove and finally a ferry across the river.

Until 1927, the only way to cross the river to Ocean Grove was by ferry and local ferryman Mr Abenathy would row you across for six pence.

Alf and Alfreda set up home back at Eildon Weir, where Alf resumed his job managing the store.

Out the front of the Eildon Weir store. Alf in a suit at the extreme left.

Alfreda had become pregnant very quickly, and the first few months of their married life had been hectic. But the still birth of the baby at seven months was attributed to a fall. It was flood time at Eildon Weir, and no doctor could get to her. A local midwife helped her through the difficulties of labour with a dead baby. She lost a lot of blood and struggled for twenty-four hours in the final stages of labour. Afterwards, she was not allowed to walk for six weeks.

Alf buried the dead child in the back yard of their little house. It was a boy, who was to have been named Peter. Interestingly it wasn’t until 1930 that “viable” still born babies had to be even reported to the authorities, and even later before they were registered. Nowadays a doctors certificate accompanies a detailed registration document, which must be lodged within forty-eight hours.

Within a couple of years the weir building project was finished, the workers dispersed and the now deserted town was swallowed up by the new Lake Eildon.

Eildon today.

Alf and Alfreda moved back to Deepdene, an eastern suburb, and Alf returned to his city job at Blocky Stone.

How to Rescue the World

ALF AND ALFREDA

Marge and Alice in their family history tapes, discuss Alfreda’s political and philosophical bent. The setting is Croydon in the 1930s. Croydon is a country town and it is the height of The Great Depression. Alf is working long hours at the Croydon Timber Yard and the family sell milk and cream from their cow. Many of their neighbours are unemployed, and homeless men come to their door to ask for work or food. In Germany, Hitler’s Nazi party is beginning to show its true colours and Russia has been a republic for less than twenty years. Alfreda is consumed by the great ideas of Politics and Economics. She shares this with Frank Hibbert, the Croydon Primary School headmaster.

Alfreda’s friend, Frank Hibbert was a progressive educator who shared her political views. His influence on the young Marge and Alice was profound.

There are also signs of early environmentalism in Alfreda’s letters. On January 16th 1935, she and Alf are camping at Yellingbo, by the creek in what is now the protected area for the Helmeted Honeyeater. She writes to Alice:

Yesterday was a beautiful day and in the evening just after sunset - oh! I wish i could tell you or show you how beautiful the bush was - for half an hour. What God has given us is so beautiful, but don’t humans muck things up - an ugly fence, a cigarette butt, an old piece of lolly paper thrown down. an old pair of shoes - everything we touch seems ugly after that beauty that I saw last night- even our bodies haven’t the beauty and grace of the wild things….. I’ll see we don’t disfigure God’s beautiful bush when we leave this lovely spot.

And later, in 1946, Alf gives us a taste of his own strong sense of social justice. He is visiting Marge in Sydney and has just received the news that Alice and Jim have managed to buy the block of land in Box Hill South that became our family home. He writes:

Your news about your block of land caused quite a lot of excitement in the family circle. Our own few square feet of land is of great importance in our lives. At last we are the possessors of what really amounts to an inheritance - a small portion of God’s earth which we can call our own. It was ordained that each man should have his share of good earth; but man overruled God’s laws and made his own, thereby making it easy enough for a rich man to obtain all the land he wants to, but placing every obstruction in the path of the poor man to obtain that which is morally his own. It is only when people, like you two, scrape to save the wherewithal, that you get your share, or rather, a very small portion of it. But I must keep off my pet theme.

ALICE AND JIM

This was the value system that Alice, our mother, has passed on to us. We were never in any doubt about which side of any particular issue was the correct one.

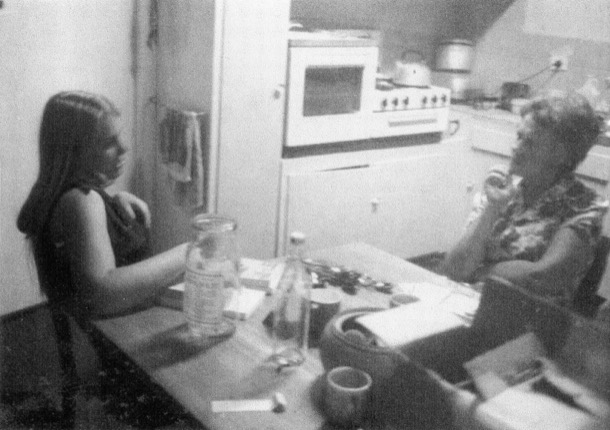

Margaret and Alice at the Moore Street kitchen table

Both Alice and Jim, our father, were staunch Labour voters, and had a strong commitment to social justice.

The world’s first atomic bomb was detonated in Japan in 1945, followed by a nuclear arms race between the USA and the USSR. Bombs were tested, and people felt that there was a constant threat of war breaking out again. Alice and Jim and a like-minded couple from our street were involved in the call for unilateral nuclear disarmament. Another neighbour, Judah Watten, a writer and a communist, was also a member of this “leftist” protest group. This was the time of anti communist McCarthyism in America, and Jim and Alice’s actions were quite radical.

Alice became more confident and able to hold her own in conversations over these years. There were many discussions around our Moore Street kitchen table about the social or political issue of the moment.

Christian social justice became her main focus during her fifties and sixties.

She was active in a number of left wing church organisations. I remember in 1975, when I was living in the country, listening to her talk on the radio about third world poverty. Even in her later years, blind and housebound, she would listen avidly to the radio and talk about politics to anyone who would listen.

Of Jim, we have fewer memories. We remember marching with him in a teachers' protest on the issue of State Aid to private schools. We are now quite used to Governments providing money to private schools, but, when first mooted by the Menzies Government, it was greeted with outrage by many. One of Jim’s concerns during the march was that he would appear on the television news and be seen by his conservative, Catholic, Liberal voting mother.

Jim was a member of the Board of Management of our family’s church, St James, Wattle Park. He was outraged when he discovered the cost of the new church building. He resigned over the issue. In his view the money would have been better spent elsewhere. This is evidence of the strength of his principles, as his role in the church was important to him.

SUE

My memories of my early twenties and engagement in ‘protest’ is of the outrage of youth. ‘How dare they!’

During my last year at College and my first years of teaching, the VSTA, the union representing secondary teachers, was very active in a campaign to improve teaching conditions. I had had an early introduction to strike action by teachers when Margaret and I marched with Dad over state aid to non government schools so I was an eager participant in the ferment.

In outrage that the State Government would contemplate increasing class sizes and teaching allotments, a couple of friends and I formed a VSTA branch and began conducting meetings. I remember calling a strike meeting and organising a boycott of classes that we were convinced would change the world. It didn't! Fancy that! We were still fighting this battle during our first years of teaching.

A much more serious concern was the Vietnam War that the US had been involved in for years and, unbeknown to the public, so had Australia! Prime Minister Menzies had mislead the Parliament and the public, and had committed Special Forces to fight in Vietnam. His successor, Harold Holt, invoking the ANZUS Treaty, upped our level of support and, as the war dragged on with no victory in sight, National Service or conscription was introduced. My family and friends were all very much against the war and the deceptive and high handed action by successive Liberal Governments. Outrage and protest was a consuming passion.

It was sometimes a bit scary! In the early days before the huge moratoriums, the numbers protesting were considerable but not large, and the police seemed to be a threatening and sinister presence. I remember the July 4th 1967 protest outside the American Consulate in St Kilda Road. I went to this one with Mum and Margaret.

It was dark as we arrived and stood with the other protesters outside the closed front gates to the Consulate. There was no visible presence in the building, as we held our anti-war banners and chanted slogans. The most sinister aspect was watching the police buses pull up across the park and disgorge many, many policemen. I remember thinking, ‘Can this be Australia?’ A noisy and highly visible minority of the protesters were quite confrontational and aggressive and were consequently arrested. We stayed well clear of the action but it was hard to avoid the police horses. They are enormous up front and personal, and were used very effectively to nudge the crowd away from the gates. Overall it was a very sobering experience and one that has stayed with me. We live in a democracy with the right to protest peacefully. What must it be like protesting under less benign circumstances?

After these small beginnings the protest numbers swelled, culminating in the euphoria of the Moratorium Marches that brought cities across the world to a standstill, including Melbourne.

The ABC captures the spirit and the times better than I can. Have a look:

http://www.abc.net.au/archives/80days/stories/2012/01/19/3411534.htm

Even though I may have wished for many thousands to take to the streets again, as they did in the Moratoriums, it has not happened on such a scale, but here’s hoping!!

The demonstrations against the Vietnam War left a profound legacy. After such a powerful and successful protest movement, it seems the natural response to feelings of outrage: paint a banner and march! As Margaret says, ‘It is part of democracy’. Aren't we lucky!

Therefore, along with thousands of other concerned people, I have attempted to ban nuclear weapons, stop the war in Iraq, stop logging of old growth forests in Tasmania and East Gippsland and persuade our government to take action to reduce emissions.

The world has changed, but not always for the better. Today, as well as the kitchen table, the letter, the banner and the march, we have at our disposal the power of global and instant communication and social media. It is the era of Get Up and ’Clicktivism’.

Sue and Margaret protesting together at Tecoma

MARGARET

July 4th 1967. It is winter in Melbourne and it is raining. The puddles flash …blue…black…blue…black…

“Link arms!” call the young bearded marshalls running up and down the line of marchers. We are marching on the American Embassy, protesting atrocities in Vietnam, pressurising our government to change their “All the way with LBJ” policy. Police horses charge the crowd. One of my companions, my forty-three year old mother, loses her handbag.

Five years later, a New Yorker I go out with a few times, assures me that there would have been fully armed Marines in the embassy, and that they wouldn’t have hesitated to shoot, had we successfully “stormed” the building.

This was my first real “demo”. I don’t remember why it was just my sister, my mother and I there. I was fifteen.

Over the ensuing fifty years, I have waved banners demanding many things: the end to the logging of old growth forests and the creation of National parks; that uranium be left in the ground; that there be land rights for our indigenous populations; smaller class sizes; a fairer allocation of education funds and more of them; that we not go to war and/or bring our troops home; that the public service not be decimated by cuts; that the separation of power between the judiciary, the legislature and the executive be maintained; that MacDonald’s stay out of our Hills community.

Most recently I marched with Michael and Chris to urge our planet to act on Climate Change:

Marching for climate justice... a family affair

The thread that links these causes, is the same thread that runs back to the 1930s around the Coates’ dinner table in Croydon. It involves words like environment, justice, democracy, fairness, equity, peace, kindness and conservation.

Great Great Grandparents

Like many Australian families, ours is a story of migration to a new country. All four of our maternal great great grandparents were European: English, German, Danish and Irish.

These four migration stories happened between the 1850s and 1870s. Three of the migrants were our great great grandparents, and one was a great grandparent.

COATES, ARRIVED VICTORIA 1860s

Coates was an English engineer who travelled with his wife to Australia in the 1860s. Their first names are not known.

The Barwon River is the large river than flows through Geelong. In the new colony, there were no iron works: the worked iron had to be imported from England, along with the experts to do the work.

Barwon Bridge then

Barwon Bridge now

We don’t know whether Mr and Mrs Coates planned to do this job and then return to England, but they would have found a thriving, wealthy colony. Gold had been discovered in central Victoria just ten years earlier.

DAU, ARRIVED VICTORIA 1860s

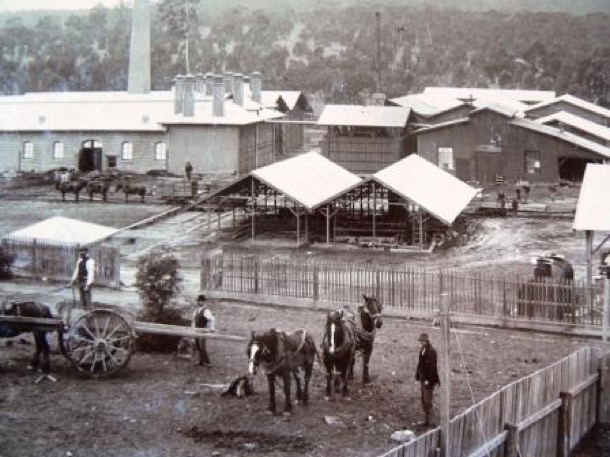

Dau was a German farmer who arrived in Australia in the 1860s. He married a fifteen year old girl, of whom we know very little. Wandong is 70 Kilometres north of Melbourne. In the years the Daus lived there, there was a thriving timber industry and some gold mining. By 1880 there was a railway line from Melbourne.

HOLM, ARRIVED ADELAIDE 1872

Roger Holm: this one is our great grandparent, a baker, who himself arrived in Australia from Denmark via England in 1872.

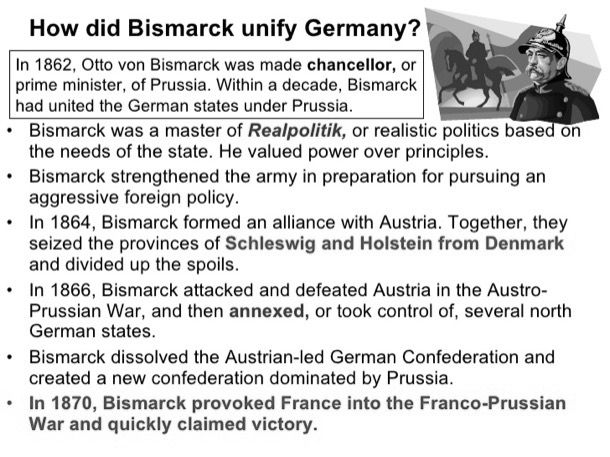

Roger had been born in a part of Denmark called Schleswig-Holstein, that had been disputed territory for centuries. At the time when he was a child, Germany did not yet exist. It was still a whole lot of little countries. When Roger was twelve, Otto Von Bismarck’s army invaded Schleswig-Holstein.

Map of Schleswig-Holstein

Otto Von Bismarck

Painting: Bismarck Wresting Schleswig Holstein From The Danes

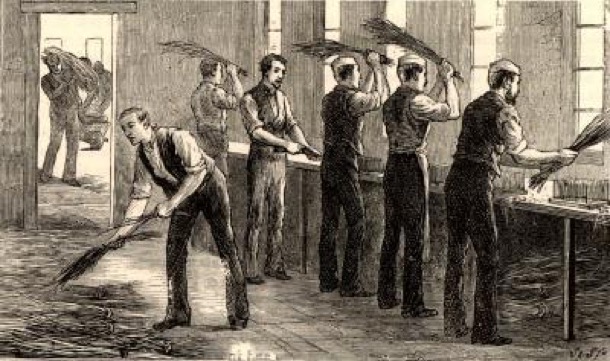

BELL, ARRIVED VICTORIA 1850s

David and Martha Bell was an Irish flax farmer, who arrived in Australia with his wife Martha (born Martha Elvidge) in the 1850s. Belfast was a prosperous modern city at that time.

The area had become a specialist for farming and processing flax, which was woven into linen, used among other things for ships’ sails.

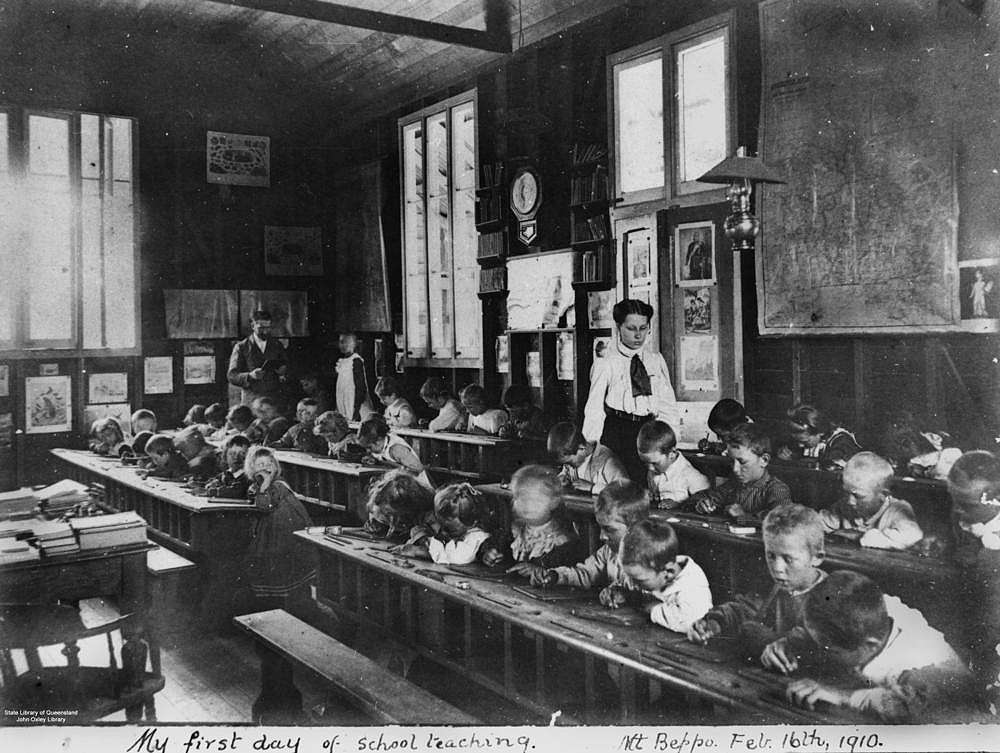

First Year Teaching 1909

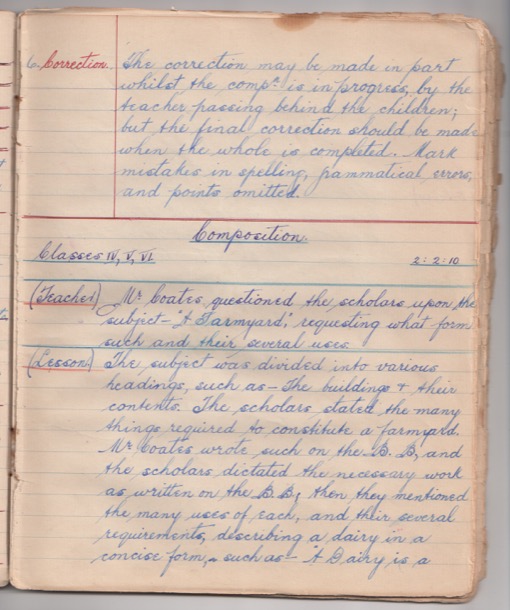

These children, photographed in 1910, are writing on slates with chalk, as did the children in our grandfather Alf's classroom in 1909. The holes in the desk in front of each child hold inkwells, in which they dipped their pens. The little children are in the front, the older ones at the back.

Alice, our mother, described her father's brief teaching career in 1909-10. The recording was made during the family history taping sessions with her sister Marge, in 1990.

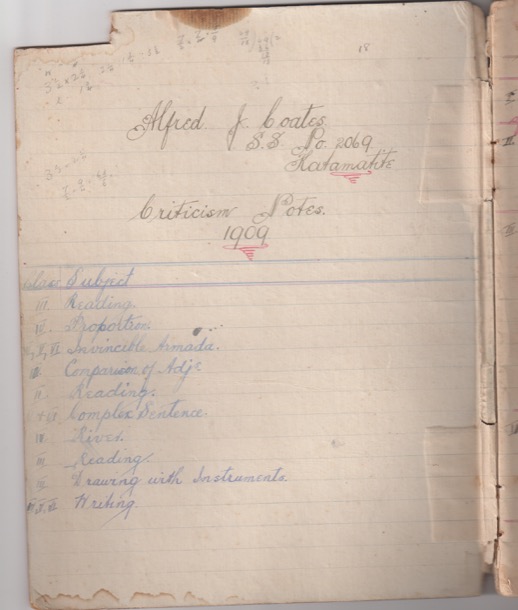

Alfred J. Coates

SS No 2069 (State School number)

Katamatite

Criticism Notes

1909

Class iii Reading

Class iv Proportion

Class iv, v and vi Invincible Armada

Class iv Comparison of Adj's (adjectives)

Class ii Reading

Class v and vi Complex Sentence

Class iv Rivers

Class iii Reading

Class iii Drawing with Instruments

Class iv, v and vi Writing

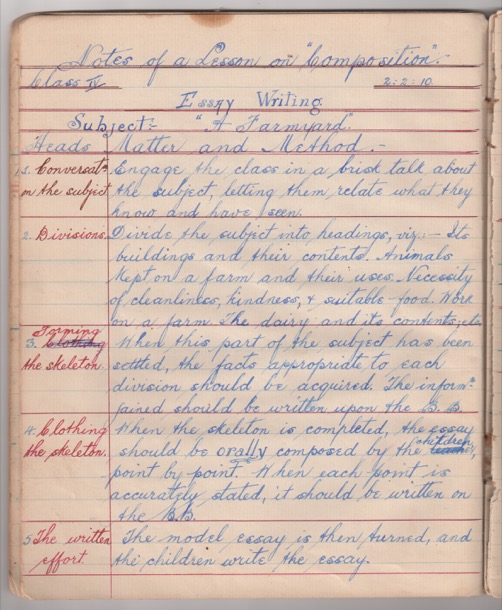

Notes of a Lesson on "Composition"

Class vi 2:2:10

Essay Writing

Subject:- "A Farmyard"

1. Conversation on the subject.

Engage the class in a brisk talk about the subject, letting them relate what they know and have seen.

2. Divisions

Divide the subject into headings, viz :- Its buildings and their contents. Animals kept on a farm and their uses. Necessity of cleanliness, kindness, and suitable food. Work on the farm. The dairy and its contents; etc.

3. Farming the skeleton.

When this part of the subject has been settled, the facts appropriate to each division should be acquired. The information gained should be written on the B.B. (blackboard).

4. Clothing the skeleton

When the skeleton is completed, the essay should be orally composed by the children, point by point. When each point is accurately stated, it should be written on the B.B.

5. The written effort

The model essay is then turned and the children write the essay.

6. Correction

The correction may be made in part, while the composition is in progress, by the teacher passing behind the children; but the final correction should be made when the whole is completed. Mark mistakes in spelling, grammatical errors, and points omitted.

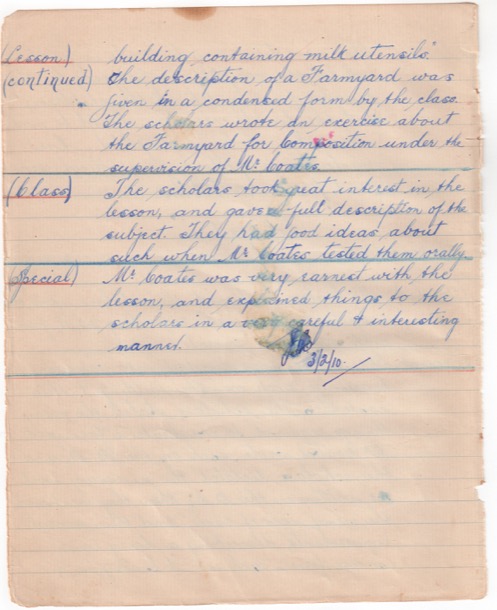

(Lesson critique by Headmaster)

Composition

Classes iv, v and vi, 2:2:10

(Teacher) Mr Coates questioned the scholars upon the subject "A Farmyard," requesting what form such, and their several uses.

(Lesson) The subject was divided into various headings, such as - The buildings and their contents. The scholars stated the many things required to constitute a farmyard. Mr Coates wrote such on the B.B, and the scholars dictated the necessary work as written on the B.B., then they mentioned the many uses of each, and their several requirements, describing a dairy in a concise form, such as - "A Dairy is a

(Lesson) (continued) building containing milk utensils." The description of a Farmyard was given in a condensed form by the class. The scholars wrote an exercise about the Farmyard for Composition under the supervision of Mr Coates.

(Class) The scholars took great interest in the lesson and gave full description of the subject. They had good ideas about such when Mr Coates tested them orally.

(Special) Mr Coates was very earnest with the lesson, and explained things to the scholars in a very careful and interesting manner.

JM

3/2/10

Alf 1910

Marge and Alice went on to discuss some other aspects of Alf's early life.

More of Alf's Teaching Notes are available in the Resources Page, which can be accessed from the Navigation Bar at the top of this website. If you are using a phone, or a tablet in portrait rather than landscape, click the tiny + under the logo and heading, to reveal the Navigation options. Our site is much better viewed on a computer or at least in landscape rather than portrait.

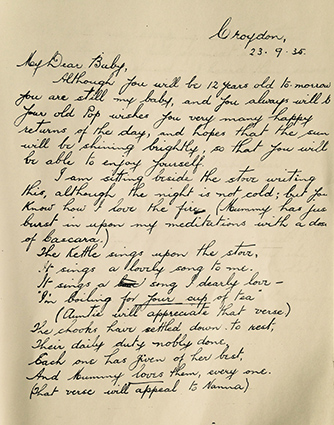

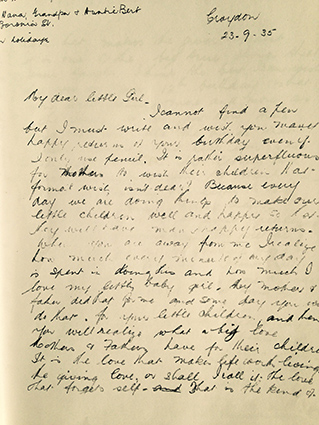

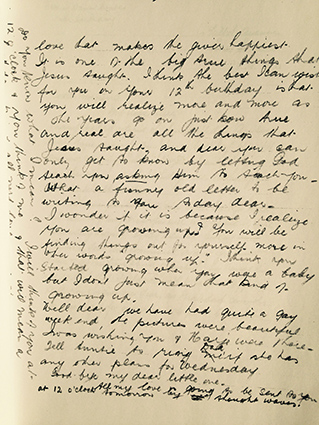

Twelfth Birthday Letters to Alice

These two letters were written to our mother Alice on her 12th birthday. Alice was staying with her grandparents , Roger and Martha Holm at their house in Boronia Street Surrey Hills. By the way, the house is still there, but more of that later in another story. Living with Roger and Martha was another of their daughters, Bertha or Auntie Bert, unmarried and with a flourishing dressmaking business in the front room of the house. Later she moved the business to Camberwell at the Junction. These letters were written by Alice's father Alfred, usually known as Alf, and her mother Alfreda or Freda. The letters reveal two very different personalities that both had a powerful and enduring influence on their young daughter. Our joint memories of the two authors of the letters are of two very different individuals.

From left Alice, Freda, Marge, Alf

ALF'S LETTER

CROYDON

23.9.35

My Dear Baby,

Although you will be 12 years old tomorrow you are still my baby, and you always will be. Your old Pop wishes you many happy returns of the day, and hopes that the sun will be shining brightly, so that you will be able to enjoy yourself.

I am sitting beside the stove writing this, although the night is not cold; but you know how I love the fire. (Mummy has just burst in on my meditations with a dose of Cascara.) (herbal laxative)

The Kettle sings upon the stove,

It sings a lovely song to me.

It sings a song I dearly love-

“I’m boiling for your cup of tea”

(Auntie will appreciate that verse)

The chooks have settled down to rest

Their daily duty nobly done.

Each one has given of her best,

And Mummy loves them, every one.

(That verse will appeal to Nanna)

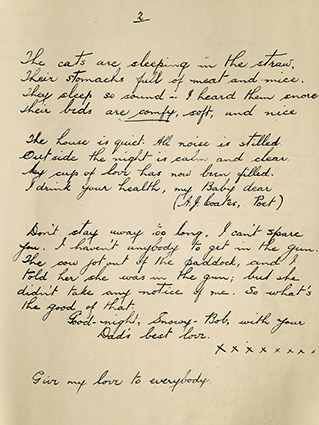

The cats are sleeping in the straw,

Their stomachs full of meat and mice.

They sleep so sound - I heard them snore.

Their beds are comfy, soft, and nice.

The house is quiet. All noise is stilled.

Outside the night is calm and clear.

My cup of love has now been filled.

I drink your health, my Baby dear.

(A. J. Coates Poet)

Don’t stay away too long. I can’t spare you. I haven’t any anybody to get in the gun. The cow got out of the paddock, and I told her she was in the gun; but she didn’t take any notice of me. So what’s the good of that.

Good-night, Snowy-Bob, with your

Dad’s best love.

X x x x x x x x

Give my love to everybody.

ALFREDA'S LETTER

CROYDON

23.9.35

My dear little Girl,

I cannot find a pen but I must write and wish you many happy returns of your birthday even if I only use pencil. It is rather superfluous for mothers to wish their children that formal wish, isn’t it dear? Because every day we are doing things to make our little children well and happy so that they will have many happy returns.

When you are away from me I realize how much every minute of the day is spent in doing this and how much I love my little baby girl. My mother and father did that for me and some day you will do that for your little children and then you will realise what a big love mothers and fathers have for their children It is the love that makes life worth living - the giving love, or shall I call it: the love that forgets self. That is the kind of love that makes the giver happiest.

It is one of the big true things that Jesus taught. I think the best I can wish for you on your 12th birthday is that you will realize more and more as the years go on just how true and real are all the things that Jesus taught, and dear you can only get to know by letting God teach you, asking Him to teach you.

What a funny old letter to be writing to you today dear.

I wonder if it is because I realize you are growing up. You will be finding things out yourself more, in other words “growing up”. I think you started growing when you were a baby but I don’t just mean that kind of growing up.

Well dear we have had quite a gay weekend, the pictures were beautiful. I was wishing you and Marj were there. Tell Auntie to ring Dad if she has any other plans for Wednesday.

Good-bye my dear little one.

All my love is going to be sent to you at 12 o’clock tomorrow by thought waves.

Do you know what I mean? I will think of you at 12 o’clock and you think of me and that that will mean a birthday kiss and all my love.

Mother

Here are Martha and Roger with Alice and Marge and other younger grandchildren in the Boronia Street Garden

Memories of Alf

“A J Coates, poet.” That dry humour is so much as I remember my papa. My strongest memories of him are from his time living in the flat attached to our house in the nineteen sixties. By that time his red hair was greying and although he was still tall, he was a bit stooped.

“What do an old spud and a man watching a football match have in common? They’re both “specked taters”. His jokes were all like that.

But his sense of humour was strangely coupled with an enduring air of melancholy. He had several “nervous breakdowns” in his life. Nowadays these would be called bouts of clinical depression.

Alf had been a very gifted student and had spent his very early working life as a teacher. The precision of his letter writing is evident in the setting out and punctuation.

We remember his collection of classics and poetry books and often he would lend them to us. He loved reading, including poetry. The “bush poets” Henry Lawson and Banjo Patterson’s best work was behind them by the time Alf was at school, but their work, and that of other Australian poets were very strongly part of the everyday curriculum. This gives a context to Alf writing a mock bush poem as he did in his letter, and signing it like that. But that wry, self deprecating humour is there too.

The other aspect of his personality that shines through is his gentle warmth. This was a time when Australian men were loathe to express such softness. Our mother told us about how he struggled with his own sense of masculinity. Although he worked in timber yards, his work was behind the hardware shop desk. He was ashamed of this. His insistence on only ever wearing black socks was seen as symbolic of his fear of being seen as a sissy. And yet here is this loving, expressive father writing to his daughter, apparently at ease with openly expressing his love.

Memories of Alfreda

Alfreda was also tall. I remember her as a rather elegant, formal figure, clad in beautifully tailored clothes, no doubt made for her by her clever sister. She had very long hair always worn in a loose bun. I do not remember her ever being without her stockings and high heeled lace-up black shoes. The two times I remember staying with Nana and Papa I can remember watching Nana in her dressing gown, sitting at her dressing table, brushing her hair and loosely plaiting it for the night. She was quite a remote figure, not one for hugs and cuddles. However, my memories are of warmth and affection towards her two daughters and her husband.

Neither Margaret or I have any memories of her obviously very strong religious beliefs, that seem to have been very much part of her everyday life and thoughts. We only learnt of these through reading her letters. It would be gratifying to Alfreda that her daughter Alice did indeed see “just how true are all the things that Jesus taught". In fact, in the latter part of her life, Alice’s interest in theology provided her with both intellectual stimulation and solace. I suspect mother and daughter were very alike.

How we remember Alf and Alfreda, in their seventies:

Historical, Social and Geographical context

Main Street Croydon, 1930s

At the time of these letters, the Coates family lived in Hewish Road, Croydon, close to where the Croydon swimming pool is today. The Great Depression of the nineteen-thirties was at its height. Alf never lost his job at the Croydon Timber Yards, even though many men did. The family kept chickens, whose eggs they sold, and a cow and had a large vegetable garden.

Alice and Marge remembered the desperate men who would come to the house for a chance to do some odd jobs around the house. The Coates family were not well off by any means, but they were grateful for what they had and shared it generously with others.

Politically the nineteen-thirties was a time of turmoil and change. Thirty percent of the Australian workforce was unemployed, and this was reflected across the western world. Economic theories about how to deal with the crisis ranged from the Keynesian “spend your way out” adopted by America, to severe austerity and cuts in Government spending practised in Australia. Political “isms” and experimentations like Communism and Nazism were being explored and discussed around kitchen tables everywhere, and nowhere more ardently than at the Coates’. Alice remembered such pearls of wisdom from her mother as “you can’t educate for goodness and you can’t legislate for goodness”.

The young Alice drank in all this talk and even as a twelve year old, when these letters were written, she was developing the philosophies that would engage her for all of her life.

Croydon, a busy suburb nowadays, was a country town, connected by rail to the Eastern suburbs and the city. In 1935 Alice would have been going to Mont Albert Central School (until Year 8) and Marge to the city based Melbourne Girls' High School, soon to be renamed McRobertson Girls' High School. They travelled on the steam train that went as far as Healesville and Warburton. Incredibly this was the closest school for them that went past Year 10. Expensive school fees were a stretch for the family, but education was valued very highly.

Our Little Allie 1895-1906

Late July 2007, on a clear winters day in Chiltern, a small Northern Victorian town I found myself standing by my great aunt’s graveside. Alice Martha Coates died on the 8th of October 1906, aged eleven and a half.

Thomas and Tessa had just been married at Nagambie and we were heading up the Hume Highway for a little R & R with Anne and Ben in the vineyards of Rutherglen. As we approached the turn off to Chiltern, 38k past Wangaratta where my grandfather Alfred had lived as a boy, we decided to have an ‘explore’. We turned towards Chiltern and found ourselves in the historic main street, complete with restored shopfronts, antique shops and the Historical Society, open for business.