Infant Jesus Catholic Church, Koroit

We began with the limestone stacks around Port Campbell and then into the primeval rainforest to Cape Otway lighthouse station.

We were on our way to Penola in the Coonawarra wine region. Google maps devised a very interesting route that took us on minor roads cross country… so interesting, varying from poor dairy, in marginal swampy land, to the red gum studded grassy plains of the western district squatters.

We passed the remnants of the volcanic eruptions; the swamps and billabongs, once much more extensive; and wide river valleys, carved out over the millennia. We marvelled at the extent of the Phragmites australis. (wetland grasses) We wondered what this entire landscape was like, prior to white settlement.

Thinking of the past and the history of the area, I was quite in the mood to reminisce about Dad as a boy, travelling to Warrnambool, especially as Google maps was taking us through Koroit where he was born. “I’ll take a photo for Margaret, let’s find the Catholic Church.” I thought.

The Catholic real estate occupies a large area of high ground in Koroit. The substantial bluestone church is typical of the area. As we drove up, we noticed the nearly rebuilt St Patrick’s Primary School directly opposite. Dad went there.

We turned and went through the church gates to the front door, and I imagined Dad and his family walking up the worn bluestone steps to Mass on Sundays. Very substantial grounds with beautiful large trees surround the church, and behind it is a large gracious building, also set in a large garden. This was the presbytery where the priests lived. It had a separate impressive driveway, flanked by large gates, and a long tree lined drive.

While I was wandering around here, Jono had chatted to the young couple painting the fence. He told her our story and she immediately offered to get the key so that we could go inside.

The door she unlocked was at the back of the church, and was where the priests would have entered the church to robe up. It sent a bit of a shiver down my spine as I thought of the stories of abuse etc. We entered the church, and, immediately in front of us, was the baptismal font where Dad would have been baptised.

Quite amazing! It is a beautiful interior, especially the wooden ceiling and the stained glass windows.

The Catholic iconography was very present in the small side chapels, and the stations of the cross.

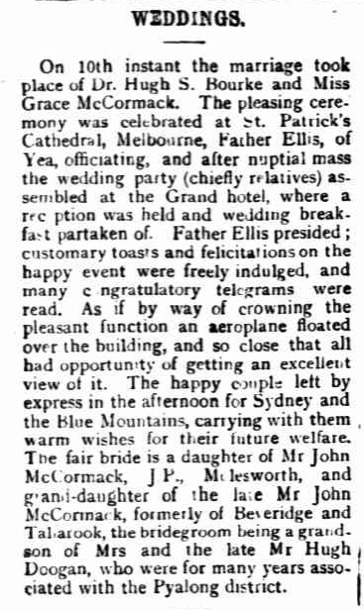

I sat in the pews and thought about our family sitting there: a respectable and important family. As the young doctor in the town, Hugh and Grace were building their family and their life here, in this very Catholic and Irish community.

As I was walking down the aisle, I thought of Dad as a small impressionable boy, drinking in all that gruesome imagery of Catholicism, made all the more fearsome in this somber shadowed interior.

We thanked Nicky for opening the church, and discovered that she was a Protestant girl who, as she said, was so in love that she converted, and was baptised and married in that church. Different times and a different story. She also told us that people said that in the past, there were so many priests and nuns here. This is also evident in the large presbytery and convent. The convent is a beautiful, gracious building, also set in a very large garden. It even has a separate chapel.

The convent would have supplied the teachers for St Patrick’s where Dad attended primary school. The school has been rebuilt and still has a thriving enrolment.

As I was looking through our photographs, I came across the one of me in the pews looking very comfortable. The thought flicked through my mind that, in another era, the title of “President of the Catholic Women’s Guild” would have been a definite option.

Are You Related to the McCormacks?

Now, after months of piecing together the McCormack and Hamilton backgrounds, marvelling at the story of three McCormack boys marrying three Hamilton girls, we were going to visit the actual sites. Very conveniently, we could stay at Sue and Jono’s property nearby. We roughed out an itinerary, and a food and wine list. The forecast was dubious, but we would mostly be in the car. Jono offered himself as designated driver.

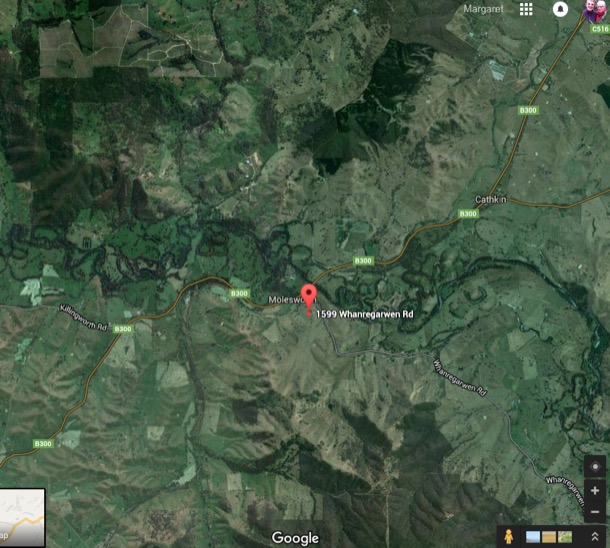

On the first morning, we pulled into Molesworth, familiar as the second last town before Sue and Jono’s road. I looked at the hall, right on the main road. We took pictures, and peered in the dirty windows.

It wasn’t until I walked down the side of the building that the significance of it all hit me. There, on a hill behind the town strip, sat Balham Hill, the red brick house our grandmother grew up in. Her father had donated the land for the hall. We noted that the hill was much too steep for young ladies to navigate.

The right turn into Whanregarwen Road was very near. We parked in the clearing next to the Rail Trail, and Sue and I climbed a rough cutting until we could see Balham Hill again, in its home paddock.

We turned to look out across the river to the hills beyond. What a view they had had. Not even the great 1870 flood would have reached the house perched right up there. And how close to the homestead the train line had been! The twice daily trains would have made their presence felt.

I thought about Grace, our grandmother growing up here, in this grand house, going to primary school in Molesworth, a short walk away. Her father, John, was an important man in the district, a Justice of the Peace and on the Yea council. When Grace was seven, the house had been extended and rebuilt.

A little further on we came across Balham Hill’s proper driveway, and a different view of the house. With her knowledgable eye, Sue noted the quality of the the land itself, and of the farming techniques, where many trees were left in the pastures.

With an eye on Google Maps, we drove on. The property up the road a bit had belonged to the previous generation: our great, great grandparents, James and Bridget Hamilton. We knew that they had selected the property, “Cremona” estate, 1220 acres, in 1866. It was “situated on the southern concave side of a great sweeping arc of the Goulburn River … rising to high ground in the south where it fronts the Whanregarwen Road.”

The "great sweeping arc” is still there, in spite of 150 years of floods and droughts. It means that the river leaves Whanregarwen Road at right angles. We stopped at that spot, looking out over the river flats. “This would have been Cremona land”, said Sue.

A farm bike pulled up alongside us. We can’t remember exactly what the man said, but it was something like “Can I help you?” but tinged with suspicion. As we wound down our windows, I thought of Chris’s quip about being ready to bail us out when we were picked up for loitering

After some explanations, Jono mentioned his and Sue’s nearby property on the Gobur Road, and it emerged that this young man, Matt Ridd, owned the business, Murrindindi Kitchens, who had put in their kitchen. The atmosphere warmed immediately, and Matt told us what he remembered of the old house at Cremona. His family, too, went back many generations in that area.

He was full of stories. The old house was gone before he was born, but he used to play around there, by the area known as the “old Cremona Drive”, where there were old bricks and things. There was an old brick lined well, down near the river, full of snakes. There had been a communal sheep wash at Balham Hill. We drank it all in eagerly.

Eventually he turned his bike around and led us up the road, around the corner to an unmarked farm gate. We took photos, and pointed to twin lines of deciduous trees that could well have flanked Cremona’s driveway.

Off in the distance the river seemed a long way down. We had read the story of the 1870 flood surrounding and isolating the original house, and of James rescuing the family in the middle of the night, by crossing a flooded creek with horse and dray. Afterwards he rebuilt the house on much higher ground. Matt left us and we drove off in the other direction towards Alexandra.

As we drove, I pictured James driving his family to Sunday Mass along this road. The story goes that he would hurry up his daughters, complaining that his “Presbyterian horses couldn’t wait all day for lazy Catholics.”

The winding road down the hill into Alexandra from Cremona, is a familiar route for Jono and me. As we arrived in Alexandra, we were looking at the town with different eyes. We passed the impressive Shire Hall and Library and wondered whether any of the Hamiltons had graced the steps of either building. Charles Hamilton, James’s only son, and heir to Cremona was Shire president three times, so he may have even been involved in their creation.

The people with the answers are now in Alexandra Cemetery, our next destination.

We easily found the Catholic section with its assortment of Celtic Crosses, the tallest belonging to Charles’s wife Hannah, who died quite young, leaving two young children and a baby.

We did not find Charles or his parents in this section, so we decided to have Margaret’s salad rolls and a cup of tea in the sun and continue the search after lunch.

In the Protestant section, we did find more Hamiltons. Agnes, James’s mother, who emigrated with him, and James himself is also on the headstone. You may remember from our previous post, that they were both Protestants. Very fitting and buried in the correct section. Buried with them, is Brigid, who chose not to be buried in the Catholic section but here with her husband and mother in law. Their daughter Sara, who died at twenty-three, is also buried here. We did not find Charles although we do know he is buried at Alexandra too. Our excuse is that this was our first graveyard and we were not yet expert headstone hunters. I will return on my next trip into Alex with my new found expertise.

That night, in front of the fire at Sue and Jono’s house, as Jono cooked our Spanikopita dinner, Sue and I poured over our notes. I opened up and reread the 2006 article we had found in the journal “Eureka Street”, where Peter Hamilton, great grandson of the original Hamiltons of Cremona, describes his own visit to Alexandra cemetery, and the site of Cremona. Right there, in the article, was the name Les Ridd.

Matt Ridd, perched on his motorbike on the side of Whanregarwen Road, had described his dad’s recent illness, and here was a story about him taking Peter around Cremona in 2005.

Matt had given Sue his mobile number, and she texted him the link. Matt immediately rang back. Sue and Matt shared more stories. It was exciting to find that real world link with our past.

Later, on the strength of our interaction with Matt, I reached out to Peter Hamilton, author of the article. More about that in a later post.

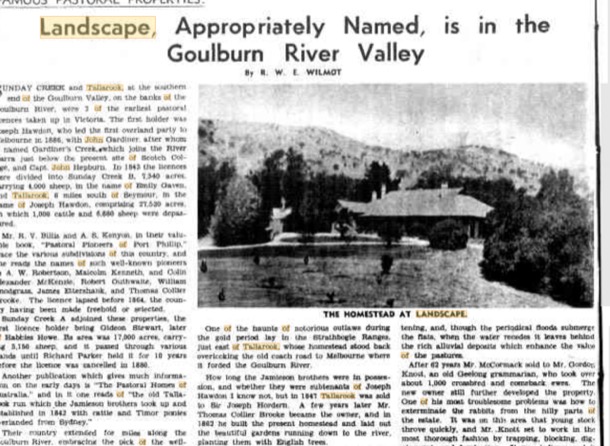

The next morning, our first destination was Landscape at Tallarook. As we drove via Yea on the same route the young Hamilton girls would have taken, we again wondered how the three young ladies travelled to the Tallarook railhead and how long it took them. It took us fifty minutes on a good bitumen road.

Originally John McCormack Snr, of Red Barn, had bought the property, then called Tallarook House. Some of his sons had lived there, and, eventually one of them, James, became its long term owner.

After they were married, James and Grace changed the name of the property from Tallarook House to ‘Landscape.’ Archbishop Little in his small family history waxes lyrical about the property and the life there.

…….’Landscape’ a more fitting name for the unique and pleasant vistas of scenery viewed from its open wide verandahs.

After settling in at “Landscape”, husband and wife took a prominent part in the social, civic, charitable ,religious, and sporting life of the community and continued to do so throughout their lives. Landscape with its gracious hostess was a perfect setting…….

It is still is a beautiful, prime pastoral property. When it sold most recently in 2017, as a much reduced holding, it still boasted three kilometres of Goulburn River frontage.

Landscape today still looks very much the gracious country house. It still sits amidst a cluster of small houses and large stone stables. The lovely old house overlooks the Goulburn and is set in a large well tended garden dominated by old stately trees. We wondered if James and Grace had planted the trees.

We wanted to stop and have a really good look, but the security cameras and the gentleman trimming the hedge were a little off putting. We settled for another drive past. On one side of the house Landscape now has its own vineyard, a more recent addition we think. Not so Tennis Court Paddock, on the other side of the house. No longer a tennis court, but we could imagine in days past it would have been a well used addition.

It was a short drive from Landscape to Tallarook. The old railway line, now a rail trail, had followed the road. It culminated in the Tallarook Railway Station, which is still in operation, on the main Melbourne to Sydney line. Back when James McCormack was establishing himself in the district, it was the railhead. Although much reduced in capacity and importance, it still has the feeling of a substantial, permanent structure. What had been high wide doors have been bricked in. There are a few historical signs, but it was hard to get a sense of the bustling, smelly, noisy place it once would have been. We took photos and moved on.

We drove into the grassy grounds of St Joseph’s. There is very little information about this church. It was blessed in July 3rd 1887 by Archbishop Carr.

It is sad to realise that this beautiful bluestone building is now virtually unused. It is not listed on the Diocese website.

Jono had sent an email to the Seymour parish priest the day before, in the hope that we might get a peek inside, but there was no reply.

The slate roof looked sound, and all the windows were intact, thanks to heavy wire screens on the outside of them. Archbishop Little tells us that “The memory of Grace and James McCormack has been retained in the Catholic community of Tallarook by the erection in St. Joseph's Church of ornate stained glass windows…”

We couldn’t really see the windows very well from the outside, but they looked substantial.

The only other buildings on the block were two little ramshackle outdoor dunnies, tucked under the trees on the outskirts of the cleared area.”

James and Grace had been dominating our thoughts in Tallarook, and now we drove on the the Seymour cemetery to find their graves.

Far from finding a quiet country cemetery, we found ourselves over the road from the busy midweek races at the Seymour Racetrack. Dodging horse floats, we turned right and parked in the cemetery grounds. We huddled quietly by the car, hoping that we weren’t intruding on a funeral still in progress. The land around Seymour is dry and stony, and heavy grey skies reminded us that rain had been forecast.

The sections in the cemetery were clearly labelled, and we headed toward the forest of Celtic Crosses in the Catholic section.

There were McCormacks everywhere. But the largest marble Celtic cross marked the graves of Grace, aged 56 and James JP (Justin of the Peace), aged 78.

We drove through Seymour. I tried to see it as it had been when James was president of the Council, but the church has been rebuilt, the town has grown, and the sad, unkempt, crowded together little houses and struggling small businesses overpower any sense of history.

Rain was still threatening, and the wind was cold, as we pulled up at the Tourist Park alongside the river in Euroa. Parked a few cars away, was Janet, who Sue and Jono knew from Trust for Nature. Janet is a local landowner, active in all local environmental organisations and activities. She was cleaning up, after running a morning water-quality training session in the river.

When we explained our mission, she exclaimed, in her larger-than-life voice,

“Oh! Are you related to the McCormacks?”

“Yes, our grandmother was a McCormack.”

It felt real. We did belong to these people: men who had dominated four local councils and been part of all the important local infrastructure decisions for the second half of the nineteenth century, and the beginning of the twentieth. Families whose weddings were written up in the local papers, whose names were on the stained glass windows in the churches, whose memorials dominated the cemeteries.

We ate our egg sandwiches and drank tea from the thermos huddled in a shelter by the river. Euroa felt older, more solid and prosperous than Seymour.

The Euroa McCormack was Thomas, the eldest of John and Jane’s children, born at Red Barn in Beveridge. We hadn’t spent much time exploring Thomas’s story, because we had been so taken by the romance of his younger brothers, James, John and Michael who had married the three Hamilton sisters. But here, in Euroa, it felt important to fit him into the story.

We had a few notes, (and a bit of subsequent expert input, to be explained later) and spent a bit of time pulling his story together.

Thomas was the eldest son of John and Jane McCormack of Red Barn Beveridge. He was born in 1851.

After living with his brothers James and Michael at Landscape, Thomas purchased a property in Mooroopna, near Shepparton, in 1882.

The property was called “The Desert”, and was in Toolamba Road. Like the other family properties, Thomas’s was along the Goulburn River, but much further north.

Soon after moving to Mooroopna, Thomas married Bridget Agnes Cooke, of Pyalong. There’s more to find our about this, but we think that Bridget’s brother John might have also invested in this property. Over time, it seems that the property developed into a “fine property” called May Park Estate.

Thomas and Bridget were active community members. In particular, Thomas was very involved with the Mooroopna Hospital Board. They had four sons and two daughters.

In 1908, Thomas and Bridget sold up in Mooroopna and bought “Springside” in Gooram, near Euroa. Thomas was 57, and Bridget, 55. It seems they immediately became involved in their new community.

In 1912, Bridget became sick with colon cancer. After a difficult two years, she died. She was 61.

Thomas remarried two years later, in 1916. We don’t know much about his second wife, Elizabeth. She was the daughter of Patrick and Elizabeth O’Connor of “Parkview”, Kilmore.

Then, in 1918, further tragedy struck. Daughter Mary, who lived with Thomas and Elizabeth at Gooram, died, aged thirty.

We can only speculate about Thomas’s motives, but, quite soon, he sold up and they moved into town. His new house was “Marengo” in Anderson St.

Thomas and Elizabeth had thirteen years together. It seems they built a busy, community-focussed life in Euroa. Among other things, Thomas was involved in the District Racing Club, the Agricultural Society, the Band, the Swimming Club and the Bush Nursing Hospital.

Thomas died in 1929, aged 78.

Elizabeth, who is buried alongside him in Euroa, lived in Hawthorn for a further fourteen years. She died in 1943.

Euroa Cemetery, like Seymour Cemetery, is in a rather uninspiring location. Separated from the town by the Hume Freeway, it sits amongst flat empty paddocks.

It was still cold and raining a little, as we approached the rows of graves, looking for the Catholic section and the telltale sign of the Celtic Crosses. Well practised now, we headed for the tallest cross.

Sure enough, we found the McCormack’s lichen encrusted, but still readable, very large granite Celtic Cross. Buried here are Thomas McCormack and Brigid, his first wife, and mother of his children, who died fourteen years before him. Only four years later, Mary their daughter also died, and is buried with her parents. Many years later, in 1943, Elizabeth, Thomas’s second wife, was also interred in this plot. She had lived in Hawthorn after Thomas’s death, but chose to be buried here with him.

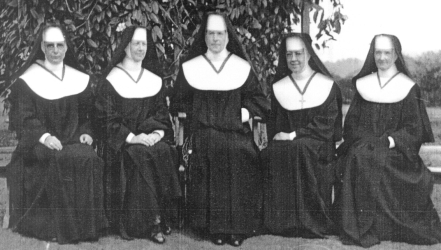

We were also fascinated to see, crowded in next to the McCormack plot, the priests and nuns of Euroa. Notably, the nuns' graves were a little smaller.

Having found Thomas’s grave we set off to find his property, Springside, at Gooram.

We drove into the Strathbogie Ranges on the beautiful Euroa-Merton Road for seventeen kilometres, and then turned right, onto a long straight road that followed the valley.

It was a lovely tree-lined road with only one or two properties along it. It seemed very remote to us. What must it have been like when Thomas and Brigid lived here?

The first indication that we were there, was a large new sign, ‘Springside’ at the beginning of a long drive that disappeared over the hill.

Of great interest though was the very large Banksia marginata on the road verge, right opposite the gate. There are very few original Banksia marginata left in the Strathbogie Ranges, and we had never seen such a large one. We wondered how old it was and if it had been growing there, as Thomas and family drove and rode past.

As no house was obvious here, we drove on. Almost at the end of the road, there was the house, sitting quietly in its old garden. It is not as grand a house as Landscape, but it looks substantial and comfortable. Thomas’s white, weatherboard house is surrounded on three sides by a wide verandah and we could imagine Thomas sitting on the verandah, looking across the lush paddocks to the distant hills, fires roaring in the fireplaces inside. It was certainly a lovely spot.

Our last day of graveyard hopping dawned cold and wet again. Very appropriate and atmospheric weather, and Yea Cemetery did not disappoint.

The old cemetery, surrounded by bushland, was tucked away on the hill, behind Yea township. The newer section of the cemetery, lies bland, uninteresting and uninspiring, out of sight.

Unlike all the other cemeteries that have been in flat and open expanses, Yea is set in a hilly spot. We arrived and walked up the small, treed hill, looking once again for the Catholic section. Not as many Celtic Crosses to guide us here and no clear signage. Near the top of the hill we began to see the Irish surnames, so the hunt for our great grandparents began in earnest. It was raining more heavily now, and we thought we were to be disappointed, but Jono saved the day.

Not a Celtic Cross, but a large impressive slab, with all that we sought buried here. It was sobering to think that our grandmother, Grace had stood here, as the bodies of John and Joan (previously called Johanna) McCormack, her parents, were interred. Maybe our father as a four year old child had been there too.

Also on the stone were John’s and Joan’s infant son Aloysius who died aged ten months and Cyril, Grace’s brother and his wife Judith. Quite a family plot.

What a beautiful little cemetery in which to end our journey around Central Victoria and how fitting to end it with the resting place of our great grandparents.

Families Along the Goulburn

It took weeks to piece together the snippets of information we had. We doubled checked information, discarded red herrings, created a timeline. We complained about the way names appeared and reappeared in different generations. We cut and pasted a colour coded chart. Finally, gradually, the stories came into focus in our minds.

Our story begins in Ireland.

Four families: McCormacks, Fords, Hamiltons and Ryans

Three of the families, the McCormacks. the Fords and the Ryans, all Catholics, all emigrated about 1848 from Southern Ireland: Limerick, Galway and Tipperary

The fourth family, the Hamiltons, were protestants, of Scottish Irish heritage. They emigrated from Antrim, Northern Ireland, also in 1848.

The Northern Irish Hamiltons arrived with some money, ready to buy land. But

our Southern IrIsh were probably driven out by the general economic turmoil and devastation caused by the Irish Potato Famine of 1845-1852.

At that time, the vast majority of the Irish Catholic population had little or no access to land ownership and many lived in appalling poverty.

Ninety percent of the land in Ireland was owned by Protestant landowners, who rented it out in small parcels to Irish tenant farmers. Already poor and dependent on the potato crop, Irish families starved when successive harvests failed, due to Potato Blight. As a result, Irish people emigrated in large numbers, land hungry and ready to and make their fortunes.

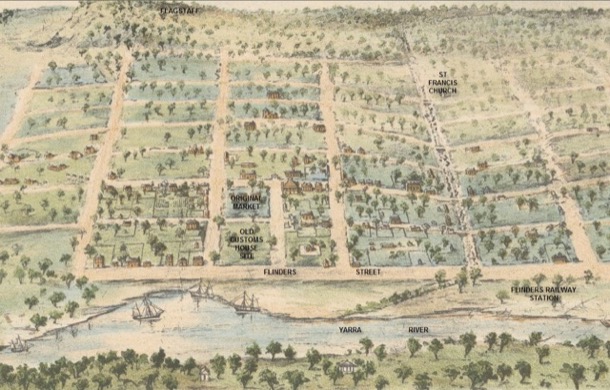

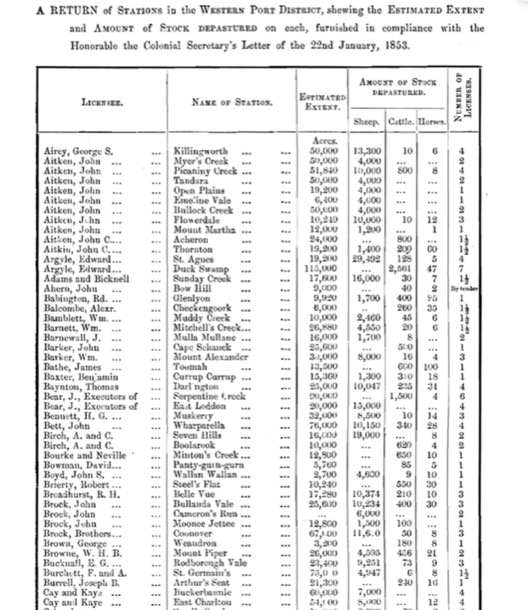

The colony the McCormacks, Fords, Hamiltons and Ryans arrived and settled in, had been ‘opened up’ by the squatters coming down from north of the Murray and inland from Portland. The Aboriginal tribes had been largely dispossessed, vast fortunes had been made, and the landed aristocracy had emerged as a powerful force in the burgeoning colony.

It is both expected and fascinating to see our Irish immigrant forbears’ land acquisition and prosperity mirrored, in the opening up of land for settlement in Victoria. This took place over several decades, primarily through a series of land acts, designed to break up the vast holdings of the squatters and encourage agricultural development, population growth, and the establishment of communities.

Between 1865 and 1890 Land Acts enabled land to be acquired at a fair price, and paid off in instalments. Specified improvements had to be made such as fencing, clearing and cultivation.

As we will see, our Irish families also benefitted from the growth and prosperity stemming from the Gold Rush. In 1851 gold was discovered in Ballarat, leading to the 1850s Gold Rush, a transformative event in Victorian history.

The colony grew rapidly in both population and economic power and our families, among others, took full advantage of the opportunities offered.

They set about the serious business of acquiring property supplying the new, lucrative, growing market with their produce. Country towns around them grew and with increased wealth, substantial civic buildings and churches were built. Railways and roads were constructed providing quicker and easier access to markets and facilitating social and family connections.

It would have been an exciting time for our four families, as they bought and developed their land holdings and participated in the civic life of the Colony of Victoria, with its own Lieutenant-Governor and elected Victorian Legislative Council.

During the first fifteen years after arriving in the colony, our four Irish Families became two couples.

1 James Hamilton and Bridget Ryan

The protestant Hamilton family from Northern Ireland comprised only a mother and son. We know that James Hamilton’s father had recently died. James was in his late teens, when he and his mother emigrated to Port Phillip, with enough capital to acquire a property in the colony. They chose Upper Plenty, which at that time was a rural area.

The Ryan family also emigrated about 1848.

About seven years later, in 1855, James Hamilton married Bridget Ryan. Bridget was a Catholic. Sue and I know something of this quandary, being daughters of a similar “mixed marriage”. The wedding was held on a property “Richland” near the Hamilton’s place at Upper Plenty. The property belonged to Mr David Johnston

Archbishop Little, who is also related to these four families and has written about them, has a bit to say about this marriage:

“… the marriage of James and Bridget was a truly valid Catholic marriage in the eyes of the Church.”

What he means here is that James would have agreed to the children of the marriage being brought up Catholics. He certainly followed through with this, even driving his wife and children to church on Sundays. Two of their daughters later became nuns.

James and Bridget stayed on for a further twelve years in Upper Plenty, where the first six of their children were born. These children included Charles, Grace, Johanna and Kate. Johanna was our Great Grandmother.

Then, in 1866, they acquired “Cremona Estate”, near present day Molesworth. They ran dairy and beef cattle and grew cereals on the rich

river flats.

Cremona homestead was "situated on the southern concave side of a great sweeping arc of the Goulburn river ….. it fronts the Whanregarwen road distant some three miles east from the present township of Molesworth" 1866:

Six further children, another five of them girls, were born at Cremona, before Bridget’s death, at the age of 56, in 1889.

Archbishop Little writes glowingly of life at Cremona, and of the three eldest Hamilton girls in particular. He describes them as “charming, refined, eligible and capable young ladies.” He describes the children’s education. An in-house private tutor taught them Art, Music and Painting, as well as academic subjects. But they all helped out on the farm as well, including the older girls, Grace, Johanna and Kate.

2 John McCormack Snr and Jane Ford

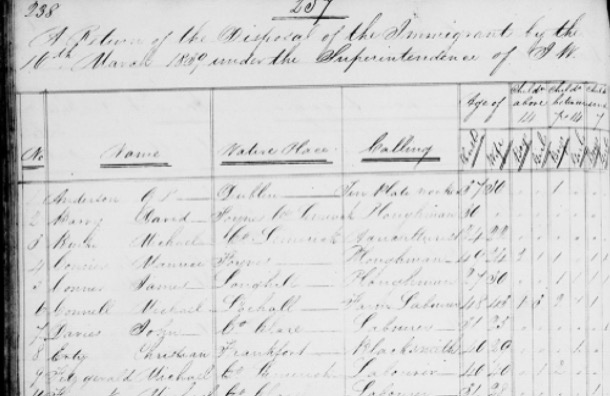

We don’t know the initial activities of the McCormack and Ford families, until, in 1850, two years after landing in Port Phillip, John McCormack (Senior) married Jane Ford at St Francis Church on the corner of Lonsdale and Elizabeth streets in Melbourne. Both had been in their late twenties and unmarried when they emigrated.

St Francis church today, the oldest still operating Catholic church in Victoria:

The couple settled near present day Beveridge, renting a property “Red Barn”. The property was very near the main road from Melbourne to Sydney. The family worked hard and developed a dairy herd, specialising in cheese, which they initially sold to passing diggers on their way to the goldfields.

Red Barn Lane today:

There was money to be made, so much, that the couple were later able to settle their sons on properties along the Goulburn River.

The first, of these, in 1876, was the eldest, James McCormack, then aged 18. His property, called Tallarook House, (later renamed Landscape), was at Tallarook, a hundred kilometres from Mebourne. James was unmarried at this stage and Tallarook House remained without a mistress for a further twelve years. Clearly, James was very involved in the community. He was elected as a councillor for the Shire of Seymour in 1887.

"Landscape" today:

"Landscape" interior:

The second McCormack to be settled along the Goulburn River, was John Jnr. His property, acquired in 1886, called Balham Hill, was near Molesworth. He also became a councillor, for Yea Shire.

Balham Hill:

Balham Hill property:

The Big Romance

So now we have three properties along the Goulburn. James and Bridget Hamilton’s Cremona and John McCormack’s Balham Hill, both near Molesworth, and James McCormack’s Tallarook House, twelve miles away.

The Hamilton girls, Grace, Johanna and Kate probably had met the McCormack boys, James, John Jnr and their brother Michael, at church. They were all Catholics.

The Hamiltons and McCormacks were a natural social fit: all pasturalists and Catholics of Irish extraction.

Archbishop Little tells us that the “Hamilton girls” stabled their horses at Tallarook House when catching or meeting the trains, and “made eyes at the McCormack boys”.

The roads between the Upper Goulburn and the railhead at Tallarook, had been completed by 1880, and the railway from Tallarook to Yea was being built from 1883. So we suppose that the road from the Upper Goulburn to Tallarook would have been a substantial one, about the time the girls were using it. Tallarook was where farm produce, etc was taken to put on the train for the markets in Melbourne.

But it’s a long way from Molesworth to Tallarook. Were they driven in a carriage of some sort, accompanied by workers from Cremona? Did they ride their own horses all that way? It was too far for a day trip. Where did they stay? And had the Hamilton girls’ parents met the McCormack boys’ parents, who lived quite a long way away, at Beveridge?

It’s a love story we can only speculate about.

But, ultimately, three Hamilton girls married three McCormack boys.

The most important to us, was Johanna Hamilton, our great grandmother, who married John McCormack Jnr of Balham Hill, in 1888.

Her sister, Grace, married James McCormack of Tallarook House in 1890

And Kate was the third sister, who married Michael McCormack. They settled initially in Berwick, and later Benalla.

The Built Environment - Box Hill

We grew up in Box Hill South in close proximity to Surrey Hills where our family has had an association for five generations. 28 Moore Street was our family home.We all spent our childhood and early adult years there, before moving out on our own. The family ventured out into Box Hill in 1946 when our parents bought a block of land in a new subdivision. They paid one hundred pounds plus ten pounds in taxes. Jim and Alice also looked further out in Donvale, where, for a fraction of the cost, they could have purchased two acres of bush. Unfortunately this was not an option as there was no public transport and we did not own a car.

After the war, Box Hill South was opened up for new housing. The City of Box Hill revised its land valuation system and residential subdivision started to boom across the municipality. The small holdings of mixed farming and orchards, were quickly replaced by the unmade road network of the subdivisions. Electricity and gas were provided, but no sewerage until the 1950’s, so it was outside toilets for all.

Our parents could not afford to have the house built, so Jim decided to build it himself. He bought a book on basic carpentry and the tools, all hand tools of course, and proceeded to build. The house is still there today, straight as a die.

It was a very liveable and rather nice design, set on stumps, weatherboard cladding and with a low slung, pitched roof. It had the standard three bedrooms ,one bathroom, kitchen, dining room, lounge room and laundry. When first built there was an outside toilet attached to the single garage that also had a chook pen attached to it.

Over time, the surrounding paddocks filled with houses and our house changed a little too. The view of the Dandenongs from the french doors in the lounge room disappeared, the toilet moved inside and our grandparents built a flat on the back. The addition of the rumpus room and flat spoilt the spaciousness of the living rooms and the back garden. The old weatherboard garage, toilet and chook pen were removed and a new double garage and new chook pen took the new additions to the back fence.

Little appears to have changed externally to the house since Mum sold it about 1981.

When we were children, Wattle Park itself consisted of large trees with mown grass underneath, like a traditional park, but with native trees and grasses. It was owned and maintained by the Tramways Board, responsible for the tram system in Melbourne. The Tramways brass band played in a rotunda every Sunday in the park. Nowadays those grasses are no longer mown. It looks much more like remnant bushland.

The 137 acres opened as a public park in 1917.

The chalet, designed and built by a Tramways architect, opened in 1928. it was promoted as a dance hall and wedding reception venue and, amazingly, it still is. It is listed on both the Heritage Victoria and National Trust Registers.

Our own parents’ wedding reception was held there in 1945, after they had been married at the Wyclif Surrey Hills Congregationalist Church in Surrey Hills.

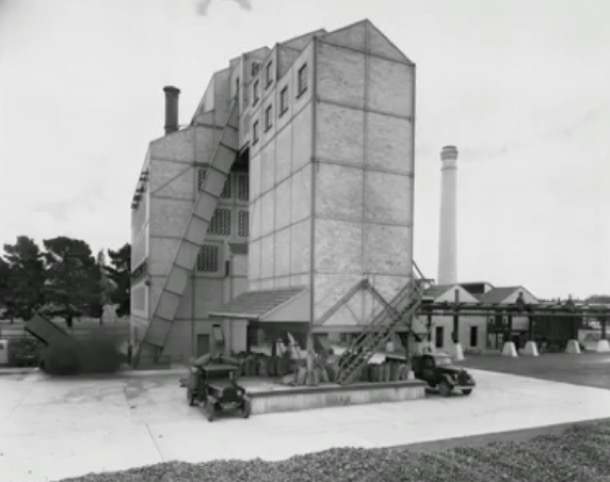

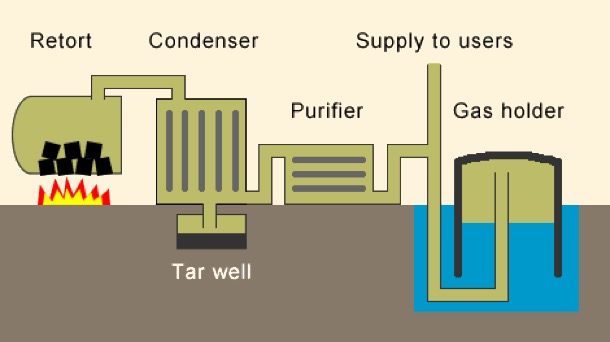

Box Hill Gasworks is now gone, but it was an important part of our parents' history. It was built early in the history of Box Hill:

7/1/1890 The Argus

Some twelve months ago the Nunawading and Boroondara councils granted permission to Mr. Thomas Coates, hydraulic engineer, to lay down gas mains in the streets of the two shires. Mr. Coates purchased an eligible site near Elgar road, Box Hill, upon which to erect the gasometer and the other necessary buildings. At the present time all the mains have been laid down in the shires named, and Mr. Coates is now in a position to light up Surrey Hills and Box Hill with gas. The local works are of such a nature that Mr. Coates contemplates being able to supply the wants of the district for many years to come without enlarging the gasworks. Last night a trial was made in Box Hill and Surrey Hills, when the corporation lamps were lit with gas for the first time. Illumination works were erected at the intersection of the leading streets. The trial was considered a very favourable one, the gas burning bright and clear. In connection with the lighting of these shires with gas a public banquet will be held in Surrey Hills next Monday night.

Over time three gasometers were built.

We don't know exactly when Jim started work at the Box Hill Gasworks, but in 1945 he left the Maribinong Munitions factory, where he had spent the war years. It was that year when our parents married and Jim moved into his in-laws’ Surrey Hills house. Soon after, he started work at the gas works as an analytical chemist. He worked there until began teaching in 1954.

Sue remembers him riding his bicycle to work, and later, a motorbike.

He worked in the laboratory, doing things like checking the calorific value of the gas.

Melbourne’s gas supply was made from Latrobe Valley brown coal, sent by rail to the various gasworks, owned by Colonial Gas Company. Box Hill was one of the biggest. As Melbourne expanded after the war, the demand for gas meant that the various gas works were very busy.

But, by 1960, substantial natural gas reserves had been discovered around Australia. Over the next five years all the Gas plants in Melbourne had closed down, and over 1000 workers were made redundant, by the discovery of natural gas deposit in Bass Strait. Over one million gas appliances in Melbourne were converted to natural gas in 1968. We remember the conversion time. There must have been plenty of publicity. Natural gas has no smell, and, for safety, they put in an additive to make it smell quite strongly. The flame was slightly different, but all the existing burners still worked.

The Gas Works are long gone. Box Hill Institute now occupies the site.

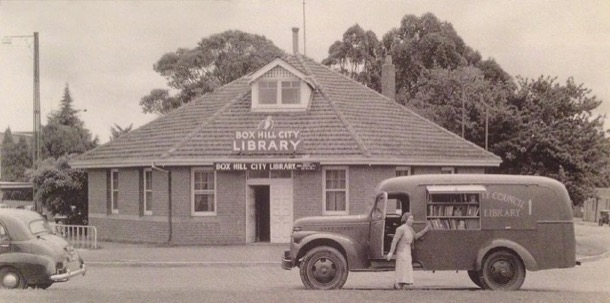

One of the fortnightly highlights in our simple lives was a trip to Box Hill Library. We loved this excursion, as we spent many hours reading on our beds. Books were expensive and we only owned a few. We had to rely on the Library so that we could finish our favourite series like Famous Five and the Billabong Books.It was very exciting if the next book in the series was on the shelf.

This small brick building was opposite the Town Hall at the end of the shopping centre. Whitehorse Road always had a wide, tree lined median strip, as it does today, and the library was right in the middle. It was later replaced by a grand modern library, but the small brick building is still there.

In our childhood, a trip to Box Hill shopping centre was quite an excursion, involving a four mile walk. In 2019 Google Maps says it takes thirty two minutes, but with small legs and a pusher as well, maybe it took a little longer. I remember it was fun and not arduous at all. The route went through suburban streets until Canterbury Road and from there it was ovals and open ground.

Box Hill Brickworks was one of the best sights on the walk to Box Hill, as the brickworks were still in full production. We marvelled at how small the men and carts were at the bottom of the quarry, and watched the procession of carts pass up and down the steep rail track to the actual brick works.

Box Hill Brickworks was founded in 1884 and was one of fifty or so brickworks throughout Melbourne, producing bricks, tiles and pipes for the building boom and ever expanding city. During the working life of the brickworks the clay was extracted from two clay holes or quarries. The first became Surrey Dive which became a popular swimming venue, but off limits to us. Sometimes however, we also gave ourselves the horrors, looking at green, mysterious waters. There were rumours of 'the dive' being bottomless and of swimmers disappearing in its murky depths. One story was of a man who took a very deep dive off the cliff side and simply disappeared. Some time later his body surfaced in Blackburn Lake, five kilometres away. No wonder we looked in awe and horror through the fence.

Today Surrey Dive is an attractive small urban lake used for swimming and remote controlled boat races.. A walking track around the ‘old dive’ and the brick works is planted with indigenous vegetation and a relaxing and attractive area.

The other clay hole was the quarry that was in operation doing our childhood. It was adjacent to the brickworks and kiln, now derelict but still heritage listed. Unfortunately no restoration work has been carried out. The kiln itself was a massive, red brick building constructed on two levels and, of course, with a huge brick chimney.

The quarry that was still in full production in our childhood, is now completely filled in. That cavernous hole in the ground is now a large mound covered in every weed known to man. On the horizon above the weeds, are the sky scrapers of twenty-first century Box Hill.

Box Hill shopping centre developed as a commercial centre, as soon as the railway line between Hawthorn and Lilydale was finished in 1862. It became an important transport hub for the eastern suburbs and beyond. During our childhood, Box Hill was the shopping destination for a big purchases. For instance, I can remember choosing a ‘walking’ doll with opening and closing eyes for a birthday present and the excitement of choosing a winter coat with a brown velvet collar. Another favourite shop was the delicatessen where such delicacies as rollmops, sauerkraut and frankfurters could be bought. Amongst the many single fronted small businesses were several large shops such as Taits haberdashery on the corner of Whitehorse Road and Station Street and Maples furniture shop. We also had a Coles variety store that sold anything from socks and singles to cosmetics, and MacEwans Hardware whose slogan was, “You can do it with McEwans because we’ve got a million things.”

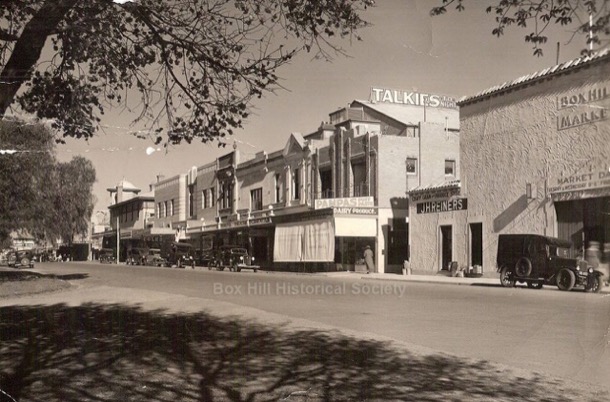

This is a photograph of Box Hill Station and the surrounding shopping precinct in the 1960s. In the centre of the photograph is the old station, that is now underground. Today, above ground, occupying the whole block surrounding the old station, is Box Hill Central and surrounding shopping malls. The signal box, the tall structure on the left of the railway gates is now occupied by the thirty-six storey golden residential tower, called Sky-One.

In the twenty-first century, Box Hill, as a commercial centre and transport hub, continues to influence the built environment around it, as you have no doubt witnessed. Officially designated as a development hub, Box Hill now sports high rise office and apartment towers. The streets we once drove down are now shopping malls, the station is underground, the railway gates are long gone and the strip shops have been replaced by a multi storey modern shopping centre. When we were children the shopping crowds were white and Anglo-Saxon. Today they are predominately Asian and the shops and restaurants reflect the change in population.

When we, as a family, first started going to the local Presbyterian church, it was called Presbyterian, Wattle Park. We had PWP embroidered on the front of our blue gym uniforms. This was before the advent of the Uniting Church. Church services were held in a cream brick building, called Forsythe Hall.

Attached, behind it, was an older little wooden building. During our childhood, this wooden building, Staley Hall, was used for a kindergarten during weekdays. In the evenings, various groups used it, including church boys’ and girls’ clubs (PBA and PGA) and the mixed club (PFA- Presbyterian Fellowship Association), we went to as teenagers. Sue and I both learnt to dance there, and I broke my front teeth on the heater in that room.

We have many memories of Forsyth Hall… dances, performances, Saturday afternoon movies, gym classes and, of course church services.

Both our parents were Elders of the church. Our mother taught Sunday School, our father ran the PFA for a while, and was on the board of management. The church was their only real friendship group, and was the only social life we had, as a family.

In the early 1960s the church community began the project of building a new church on the site. The size and scale of the project was a source of much disagreement between our father and others on the management committee.

In the end, a very grand architect designed building was commissioned. The new building was designed by well known architects Chandler & Patrick. An 1887 pipe organ was relocated from a church in Melbourne and extensively rebuilt. The new church, renamed St James, opened in 1965.

I loved it, because I sang in the church choir, and it had a choir loft at the back and great acoustics.

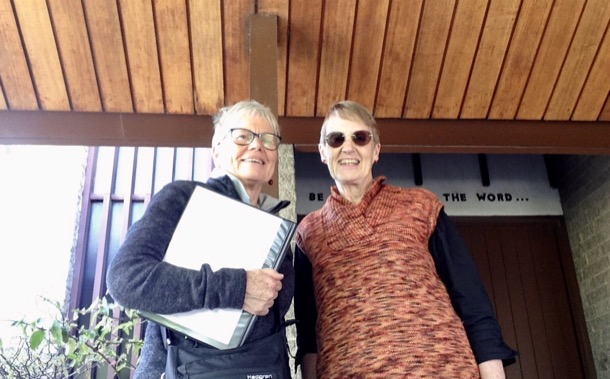

The buildings are still there. Sue and I visited as a detour on our “back to school” walk in 2016.

The Built Environment - Hawthorn

These posts can be viewed as a virtual pilgrimage of the structures and buildings in Melbourne and how they relate to our family. Melbourne is undergoing a tumultuous time of change, as, in 2019, its population grows to nearly five million. Our family landmarks are inevitably caught up in the changes too, as you will see.

Our first post covers the suburb of Hawthorn.

Glenferrie Road

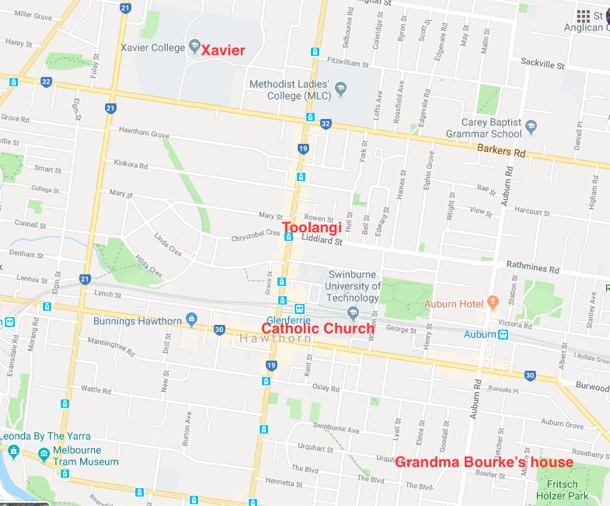

733 Glenferrie Road is listed on the Glenferrie Road Historic walk as the ‘historic mansion Toolangi. It was built in1905 as a doctor's surgery and residence for William Clayton, physician and surgeon.’

This house is significant to our family as two generations of Bourke doctors lived and worked here and our father spent his teenage years here.

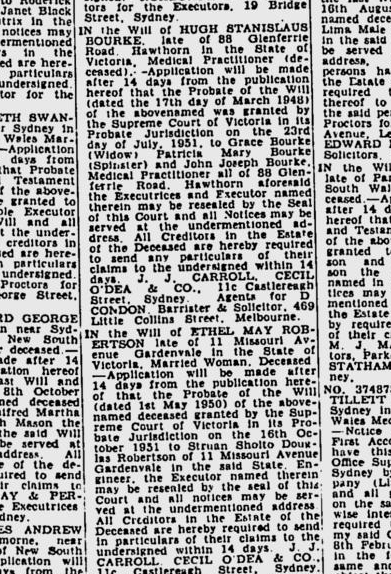

It was in the late 1930s that our paternal grandfather Dr. Hugh Bourke and family moved to Glenferrie Road from Koroit. Presumably Grandfather Bourke bought both the property and the medical practice.

At this time, our father was at secondary school at Xavier, where he had boarded until the move. He continued to live in the Glenferrie Road house until he was married in 1945.

After Grandpa Bourke’s death in 1950, Grandma Bourke moved out and Dad’s brother Jack and his family moved into the house. Jack took over the practice, which he ran until he retired.

I have clear memories of the house, both visiting Uncle Jack and, once or twice, the surgery. The house seemed enormous and imposing, and as we mentioned in a previous post, the paraphernalia of Roman Catholicism was very evident. Uncle Jack also had a greenhouse in the back garden where he grew orchids and Christmas Lilies. The garden shed and the greenhouse where still there until recently.

I still associate the perfume of Christmas Lilies with visits to Grandma Bourke at Christmas.

The building next door to Toolangi was the Hawthorn Motor Garage, built in 1912 . From the 1920s the garage was run by Albert James Kane and family, who had it for 20 to 30 years. They introduced the first electric petrol pump in Hawthorn.

The Hawthorn Motor Garage building is on the Victorian Heritage Register. It is the oldest known purpose-built motor garage in Victoria. Dad would have been very familiar with the Kanes and the garage: while courting our mother, he was lucky enough to be able to borrow his father’s car and use his petrol coupons to fill up at the garage next door. As it was wartime, petrol was strictly rationed but doctors received extra coupons, that Dr. Hugh obviously allowed his son to use.

In April 2019, when we visited it, the site of the house and the garage were in the process of being redeveloped. The garden and out buildings have been cleared away but the main structures of the Hawthorn Motor Garage and Toolangi remain. They will be repurposed as part of the new apartment complex being built on this corner.

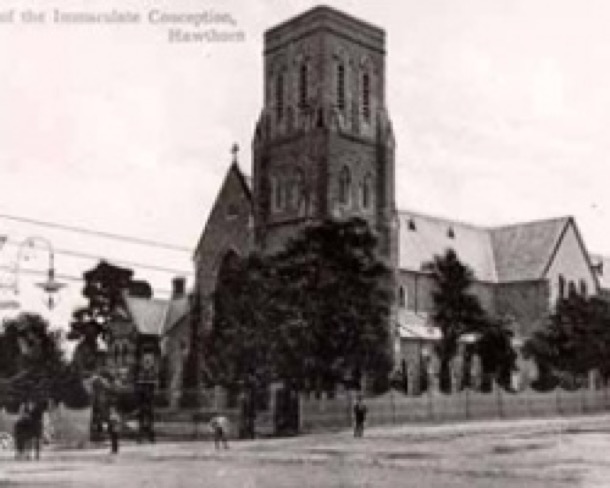

At the other end of Glenferrie Road shops is the Catholic Church. An imposing bluestone structure, the Church of the Immaculate Conception still dominates this busy corner. The Bourke family would have attended Mass here every Sunday. Now I walk past here every six weeks on my way to have my hair cut. Time marches on.

Urquart Street

After our grandfather Hugh’s death in 1950, Grandma Bourke moved a few streets away to Urquhart Street, still in Hawthorn, leaving Jack to bring up his family and run his practice from the Glenferrie Road house.

We remember this house well. Grandma Bourke was a keen gardener whose beautiful roses and bulbs were fertilised by the manure from our parents’ chooks. A huge weeping deciduous tree in the front yard afforded a play area for visiting grandchildren. The house was big enough for our aunt and family, who lived near Warrnambool, to stay over Christmas.

It had a coal cellar, accessed by a trapdoor on the back verandah, with fed the coke heater.

The house looks much the same in 2019, as it did sixty years ago, when Grandma served cake and tea in beautiful china in the front room to her visitors, and mugs of tea with slabs of bread and butter to workmen on the back verandah.

Xavier College

Our uncle and father, first went as borders to Xavier College for their secondary eduction. When our father began there in 1932, Xavier had already been there for fifty years. It was and still is, the premier Catholic Boys private school in Melbourne.

Initially they boarded at the preparatory school, Burke Hall. The buildings of Burke Hall were put together from a trio of mansions on the hill known as Studley Park, some bought by, others bequeathed to, the Jesuits. It first opened, as Xavier College’s junior school in 1921.

Xavier’s senior School is even older. The South Wing is the original building of Xavier College. The foundations date from 1872, the front dates from the opening of the College in 1878, the back half was completed in 1884. It was listed by the National Trust in 1987.

Xavier’s main chapel would have been being built when our father arrived. It was finally completed in 1934. The chapel is a fine building with a huge dome. I have sung in a concert under that dome, and Sue has been in the audience for another concert there.

Poowong Footage

In 1976, close to my 25th birthday, Fred and I visited our father and his wife Bev and Bev’s two young sons, Grant and Scott, at their fairly newly acquired property, the old Poowong homestead. Fred, the chronicler of our lives, with his trusty movie camera, recorded the visit on film. Until Fred sent it to me recently, I had not remembered the visit.

The significance of this particular flickering footage of Poowong rests not only on the fact that it is forty years old, not even on the fact that 1976 was during a short window in which we had a fairly normal grown up daughter-father relationship. Its power is much more recent.

Our father died three and a half years after this film was taken in early 1980. He was not even sixty. There was a family history of heart disease, and although, there were occasional bursts of a sunny warm personality, the Jim we had known for most of our lives had been tightly coiled and tense.

As Sue and I watched this footage: our fifty-five year old father walking the paddocks: strong, handsome and happy, clearly happy, I found myself bringing up the possibility of sending this footage to that other family. They had had him for such a short time. We looked at each other in amazement. The process of exploring and exposing our own pasts in this blog, at first staying with emotionally safe pathways, then probing gently the uneven terrain of long disused dark tracks, has led us both to this place. Together we marvelled that our long held animosity and rancour, seemed to have just … dried up.

After getting Fred’s permission, and after a little internet sleuthing, I found a family contact. I sent a tentative paragraph, using Facebook Messenger, together with a link to the film. There was an immediate response.

Bev, still living in that Poowong house, was very appreciative. She said it brought back “lots of great memories”. And apparently lots of us old ladies are good internet sleuths. Bev had been following this blog all along, and she has subsequently sent us some family history booklets and photos.

The family contact I had found was Robyn, wife of Grant, one of those little boys in the film, and Grant has a very special interest in this story. By chance, I had sent the footage to the very person who had found Jim, after he had died. In Grant’s own words:

One of the reasons for our move to Poowong was the poor health of my stepfather. He had suffered a serious heart attack and had been pensioned out of the teaching service, and a less stressful lifestyle was recommended. Sadly for Jim, he would only enjoy the more sedate lifestyle for two years, as he passed away early in 1980.

… Every summer without fail, my family would join with my mother’s sister’s family in a month-long Christmas vacation at our big old (holiday) house. The summer of 1980 was no different except that, at the end of January, Jim and I returned to Poowong to attend to some work around the farm, leaving my mum and younger brother still vacationing at Inverloch.

It was one of those long daylight saving summer days and, towards the evening, Jim set off to search our boundary fence for his tobacco pouch that he had lost during the day. He had been gone for a long time and it was almost dark, so I decided to go for a walk to find him. My dog Butch led me out to the side paddock, and immediately ran to a steep incline covered in long grass, by our fence line. The world today is permeated with death, and even children as young as eleven are far too familiar with its many faces. But for me at eleven years old, death was foreign and the stuff of nightmares. To me at eleven and to me now at 44, it will always be the same - the face of a 58-year-old man drained of blood, sheer white, pale blue eyes staring up into a twilight sky. Jim died of a massive heart attack leaving me alone on the farm, waiting for mum’s ritual telephone call that night.

The details of the chaos of that night and the weeks ahead can be imagined. The trauma inflicted on our family was immeasurable, as anyone who has suffered an unexpected loss would know.

A few months after this, Grant had a life changing experience on the very spot where he had found Jim’s body.

He goes on to write, In the more than 30 years since that experience, I have had much time to reflect on what it means to me. It has given me great comfort at times and has given me an unwavering belief in the hereafter.

Inspired by this, Grant went on to investigate and research the Paranormal, travelling throughout Gippsland, interviewing people and compiling evidence on some of Gippsland’s greatest mysteries. His book, “Great Gippsland Mysteries” was published in 2014.

The Pakenham Bourkes 1939 - 2017 Part Two

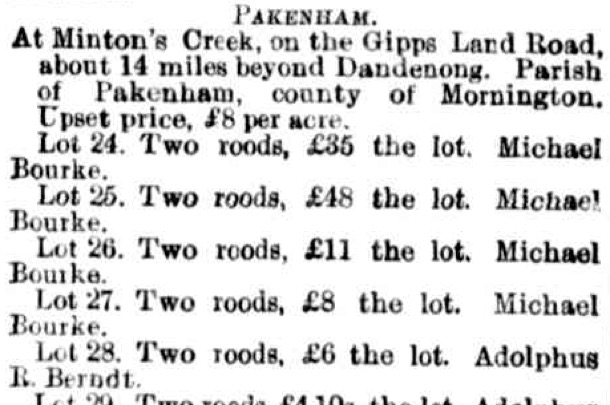

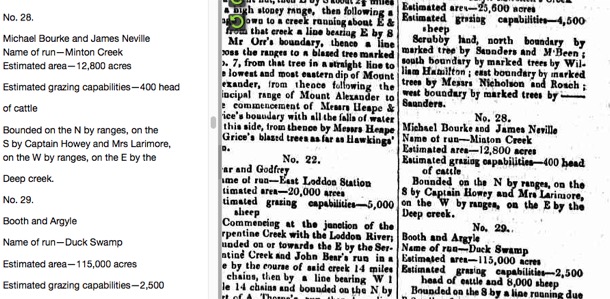

This example and a number of others are parcels of land around Pakenham.

Much of this investment was aimed at establishing their sons on large local properties.

Michael became an important citizen in the very early days of the Pakenham area. He was an inaugural member of the Berwick District Roads Board. Later this Board became the Berwick local council. Three of his sons were to spend time as Berwick Shire councillors, each of them spending time as Shire President. Michael was also post master and a trustee for the church, the school and the local cemetery. There is also record of nine nephews and nieces coming to Australia from Ireland, each receiving the best he could afford.

Michael died in 1977. Catherine took over the business and became quite a force in the district in her own right.

She lived into her nineties, dying in 1910. Her obituary describes her colourful life:

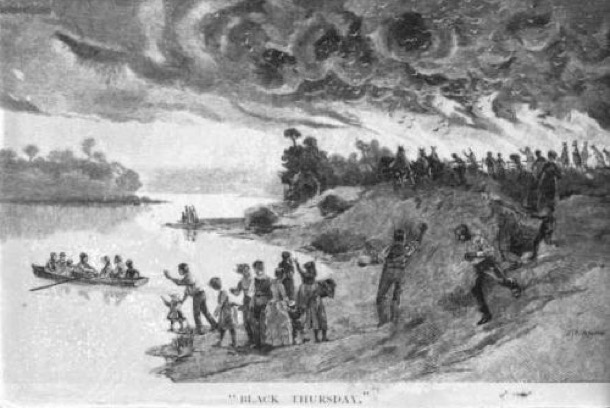

South Bourke and Mornington Journal Wednesday February 2, 1910

It is quite true to say that never in the history of this part of Victoria has the death of anyone been the general subject of so much interest and discussion as that of the late Mrs. Bourke who, with her husband, was one of the first settlers in Pakenham. The deceased lady was married in Ireland to Mr. Michael Bourke in the year 1838, being then 20 years old. Evidently the plans for their future had been prearranged, for the same day they shipped and sailed for Australia, arriving in Melbourne on St. Patrick's Day, 1839. They obtained employment as soon as they landed, managing a dairy farm at Moonee Ponds, where they remained until 1844, when, having saved money,they took up a run under a squatter’s licence on the Toomuc Creek, opposite Grant's orchard, then known as Bourke and Neville's station. There they remained for a number of years, until shortly before Black Thursday Mrs Bourke and her family took possession Bourke's Hotel, at that time known as the "Latrobe Inn," the husband remaining for a time at their station. On Black Thursday the whole district was in a blaze, and whilst Mr Bourke was trying hard to save the station property (water having been exhausted milk was brought into play and ultimately the run saved) word was brought to him that the hotel property at Pakenham was surrounded by fire. Galloping down there he found his wife and her children had saved themselves by crouching in the water in the bed of the creek. This is only one of many thrilling incidents in their lives.From the time they first arrived in this district to the time of Mr Bourke’s death in 1877, as they made money, they at once invested in land. Banks were unknown this side of Melbourne in those days, and their investments invariably turning out profitable, they slowly but surely acquired wealth. The name of Bourke and Bourke's Hotel will be, for generations to come, remembered as the pioneers and landmark of this part of Gippsland. The lives of Mr and Mrs Bourke have clearly proved what thrift, hard work and stout hearts can do in the settlement of this country, for at the time they arrived, the country was full of blacks camps along the banks of Toomuc Creek, and the country dense bush mostly. Yet out of all this Mr Bourke. made a fortune, buying up land as far away as Dandenong, and settling his sons on the land.

After his death Mrs Bourke continued to carry on and work hard, when there was no call for it, on the hotel property, and, as she repeatedly told the writer of this, she had more than her reward in the welfare and prosperity of her family, and she was proud of them, and well she might be, for her three surviving sons, Thomas, Daniel and David, have all been presidents of the Berwick Shire council, and all hold His Majesty's commission as Justices of the Peace, whilst the daughters are comfortably settled and highly respected. One of one of them, Miss Cissy Bourke has been (and still holds the position) of post mistress at Pakenham since a post office was first created.

With daughters like these, and sons holding the high positions they do, ever ready to give of their time and money in advancing the interest of the township and district, Mrs Bourke. has gone to her rest feeling fully rewarded for the years of her life devoted to and spent for their good. It would be difficult to find in the history of Australia, a parallel case of a man and a woman rising from the humblest rank of worker leaving behind them such a fortune and family so respected.

Mrs Bourke was probably the oldest colonist living at time of her death, having attained the ripe age of 91 years, being a colonist for 71 years and having resided at Pakenham for the last 67 years. She is said to have never, had a day's serious illness, and death was hastened by the severe heat three weeks ago.

Mrs. Bourke who died, on the 24th January at 9 in the morning, was-interred in the Pakenham cemetery on the 26th. A solemn Requiem High Mass was held in St. Patrick's Church from 10 to 12 a.m., the coffin being heavily draped in mourning, thronged with relatives and friends of the deceased. At the close of the Mass, the coffin was carried to the hearse and proceeded to the cemetery, a procession of carriages and horsemen fully half a mile in length and composed of people of all creeds following, and so was laid in her last resting place with sorrow and with respect: a good mother, a kind hearted woman, and a true colonist.

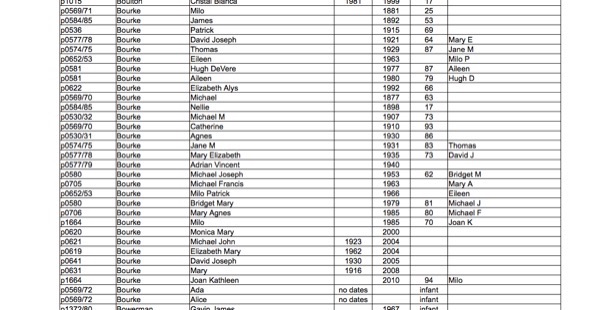

Michael and Catherine had fifteen children in total. Here in birth order is what we know of each of them:

James, born 1839, at Moonee Ponds. He was married twice: first to Johanna Conway in 1867, and secondly to Margaret Cahill in 1877. He had ten children all together, all girls. James’s property was in Dandenong, near the corner of Dandenong Road and the M1 freeway. He died in 1892 and is buried at Pakenham Cemetery.

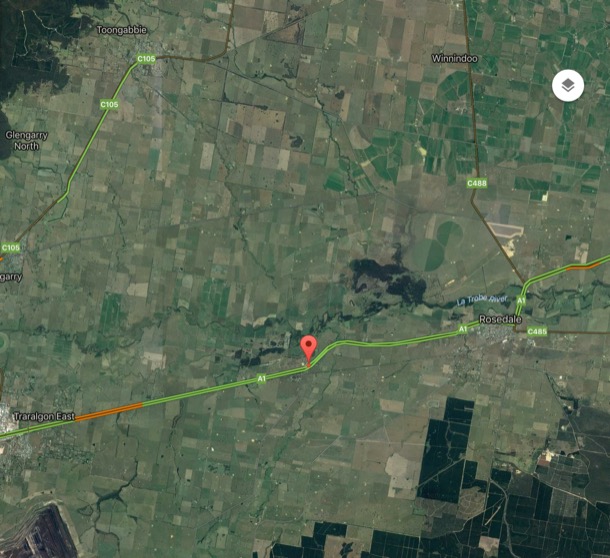

John was also born at Moonee Ponds, in 1840. He married Mary O’Neill in 1877. John and Mary lost their fist two children in infancy, but went on to have another five. The family settled in Leawood Park Rosedale, a long way from Pakenham. Today, Leawood is an Angus stud farm which has been in the same family, the Stuckeys, since 1944. It is a covenanted Trust For Nature property, protecting 18 hectares of important floodplain habitat along the Latrobe River.

John died in 1892, He is not buried in the Rosedale cemetery, but his son John who died aged 4, a year before John senior died, is there. Mary went on to live until 1935.

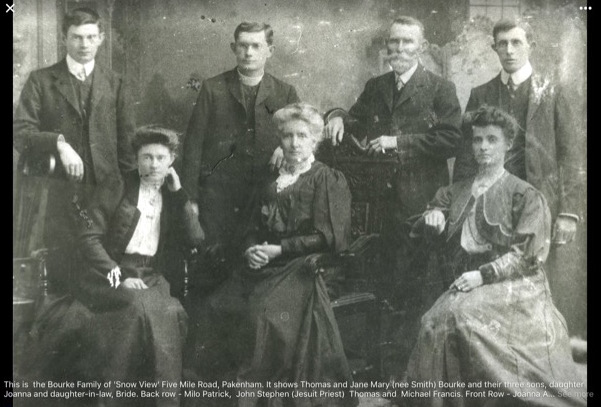

Thomas was Michael and Catherine’s third son, also born at Moonee Ponds, in 1842. In 1875, Thomas married Jane Smith, daughter of another family who came from Shanagolden in Ireland, and settled in the Toomuc Valley. The Smiths probably travelled from Ireland on the same ship as Thomas’ parents.

Thomas and Jane moved to the property “Snowview”, which Thomas had “selected” some time earlier. They had four children. Thomas, like his father, was very prominent in local politics, serving on the Berwick Shire Council for forty-five years. During most of that time he went on horseback from his home at "Snowview" to attend the meetings at Berwick, and it was only through advancing age that he finally resigned from the council. He lived at “Snowview” right up to his death in 1929. It is now a heritage listed property, which remains in family hands to this day.

Thomas and family:

Mary Ann was born a year later, in 1843 the last to be born at Moonee Ponds. Mary died aged six. We know very little about this Mary, we don”t even now where she was buried. The family was living at Minton’s Run when she died, perhaps she was buried near the slab hut they lived in. The Pakenham cemetery wasn’t formally gazetted until 1865, though, reportedly, there were burials there before then. A devastating fire in 1944 burned most of the wooden grave markers in the cemetery anyway, so much of the historical graves are now unmarked.

The fifth child is Michael, born in the slab hut at Minton’s Run in 1844. Unlike the other sons, Michael did not take up life on the land, but became a lawyer. He married Ellen (Nellie) Doogan in 1884. Nellie was the daughter of Pyalong publican, Hugh Doogan. The family lived in Parkville, near the city of Melbourne. Michael and Nellie had six children, the second of whom, Hugh, was our grandfather.

Michael died in !908 and is buried with Nellie and their third son Austin, in the Kew cemetery.

Michael and Nellie's Parkville house:

Michael and Nellie's grave:

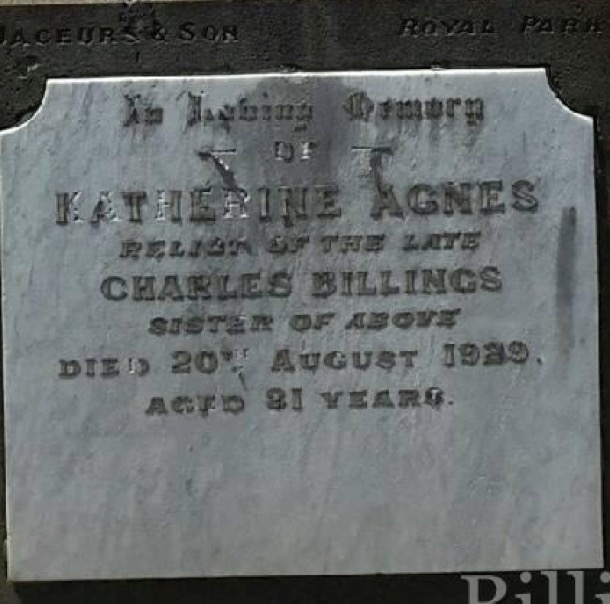

Catherine is the sixth child. She was born in 1845 at Minton’s run. She married Charles Billings in 1878. They lived in Prahran, in a house named “Pakenham”. It seems to have been an important family place, with births marriages and deaths all occurring there. Charles and Catherine had seven children and Catherine died in 1929, and is buried in the St Kilda cemetery with her sister Mary Lucy.

Daniel Bourke, was born in 1847. He was Michael and Catherine’s fifth son, Upon retirement from the Berwick Council, he is quoted as saying, “Our nation was not built on bloodshed, but on hard work”.

Daniel, like almost all of his brothers lived out this ethos on the land. Michael and Catherine seem to have imbued their children with the desire to do well, serve their community and ensure that their own children were also settled well. Daniel followed the family line. He married Fanny Levers who produced eight children and pre-deceased Daniel by only three years.

Daniel’s early years were spent in Pakenham where he owned Mt Bourke, some 400 acres, sold off from a larger property owned by the Hentys. This property is now in central suburban Pakenham, as we mentioned in the previous post. The heritage listed house was built one year after Daniel sold the property, probably by the new owners. David also owned the Gembrook Hotel in Pakenham.

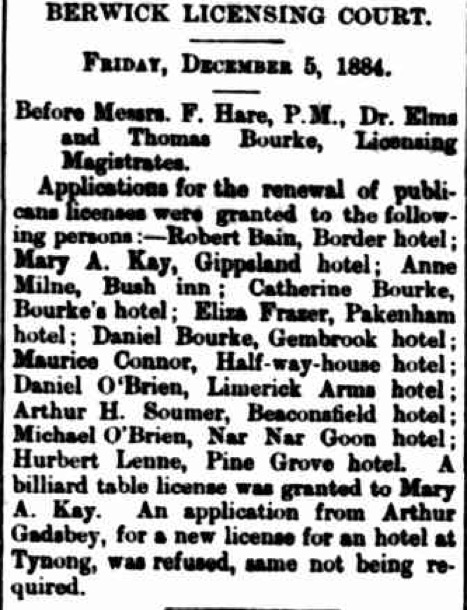

What is notable about this article is that it also includes Catherine’s application for Bourke’s hotel, and Daniel’s brother Thomas, is the licensing magistrate!

It is Daniel’s public life in Pakenham that gives us some idea of the man. Daniel served on the Berwick Council for twenty years and it is the speeches from his farewell dinner that offer these insights. Fellow councillors were obviously very sorry to lose his services, as they commented that,

‘…his name will be remembered in Pakenham with pride and honour..’

‘Berwick Shire is losing on of its leaders.’

‘He was one of the largest-hearted men in the district….’

‘His calm, cool, warm-hearted manner won him friends from all ranks. He was in the full sense of the word a reliable man and a gentleman.’

Daniel held many other other positions the community, as President of many clubs, farming organisations, and was also regarded as a pillar of his Church and well regarded by others…’

Daniel’s own speech in reply to all these accolades is also revealing. In reply he says that it was the noblest duty of a man to help his neighbour and the magnificent national feeling that was through gathering particularly pleased him. Australia to him was the greatest country in the world.

This offers an insight into Daniel’s character but also to the ethos that appears to run through the family, and no doubt contributed to their success.

Daniel and his family moved to Stratford where he and David, his younger brother of Monomeith fame, owned another property, ‘llowalong’. Daniel and his and wife felt that there was not enough ‘scope’ for their sons in the district and it was for their sake they were leaving Pakenham. Daniel died at the ripe old age of 88 leaving one of his sons possibly James on the Stratford property.

Mary Lucy was probably the last child to be born at Minton’s Run. There are doubts about the date of her birth. Mary Ann had recently died, and this Mary was perhaps given her name. She died, unmarried and is buried in the St Kilda cemetery. On her grave it says she was aged 37, but this would make her born the same year as her namesake Mary Ann. Had she lied about her age? Is the information about the two Marys wrong, and they are the same person? We don’t have a grave for Mary Ann, so there are unanswered questions about these two. The fact that Catherine was buried in the same grave as Mary Lucy, and near to Prahran, when Catherine lived suggests that the two were close. Perhaps unmarried Mary lived with Catherine and Charles.

Ellen was the first child to be born at Bourke’s hotel right in Pakenham. She was born in 1851, the year of the big fire that burned the Minton’s Run property. She married John Augustus McKeone, of Port Albert Victoria. The couple lived at times in Beechworth and in Narrandera. They had a total of nine children. John died in 1895 and Ellen in 1934.

Milo was born in 1852. He never married. He died aged only 25, “after a short illness” at the home of his older sister Catherine, and is buried in the Pakenham cemetery.

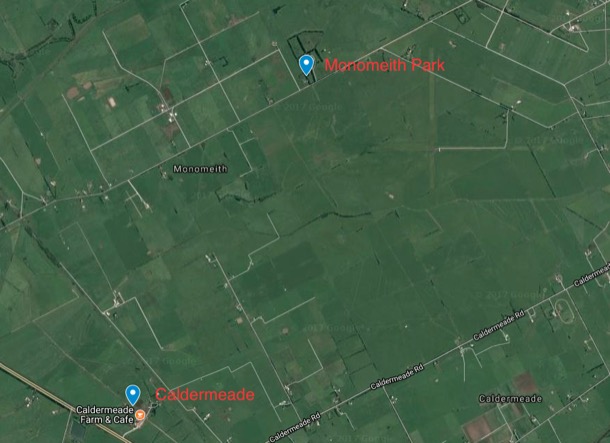

Michael and Catherine’s youngest son David, was born in 1856. He married Mary Hunt in 1888. David had bought Monomeith Station in the mid 1800’s. It was originally 3000 acres comprising what is now the area of Monomeith and Caldermeade.

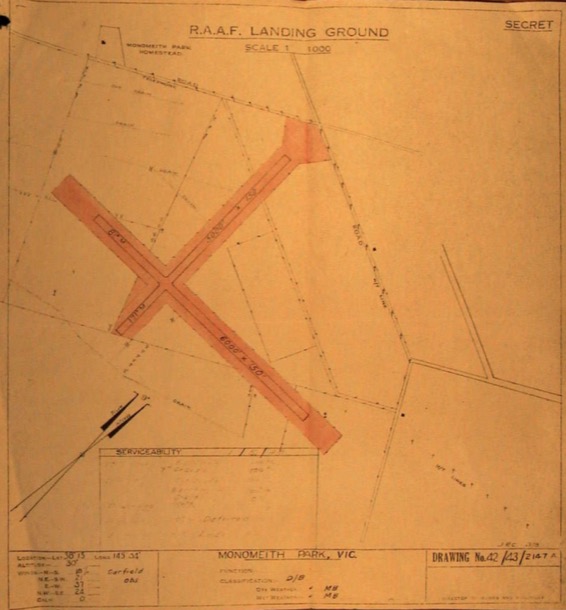

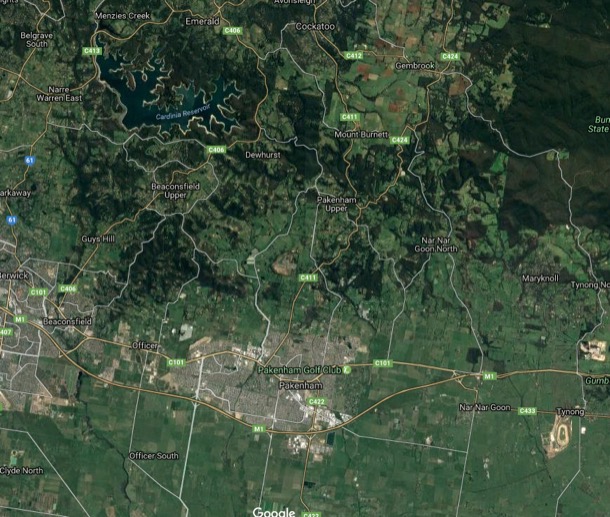

On the map you can see the World War two airstrip, south east of Monomeith Park. It was constructed as a RAAF fighter base to protect Yallourn where all of Melbourne’s power came from. In the end they only built two gravel strips, in the shape of a cross.

It was fine grazing land on black loam country and is part of the rich history of the early settlement of the area. Over the years hundreds of prime bullocks were driven to Newmarket sale yards in large mobs. According to local legend this feat was undertaken by the well-known character “little” Billy Matthews who reputedly drove the Monomeith mob all the way by himself.

In 1886 1000 acres of Monomeith was sold at auction, probably the swampy section. The carrying capacity of the land retained is referred to in, “Memoirs of a Stockman” by Harry Worthington Peck:

“However, the Bourke brothers [David’s sons, Michael and Hugh] at Old Monomeith Homestead of some 2000 acres have today the pick of the estate carrying some 3000 cattle of mixed ages and all fattening. This is probably a record for the Commonwealth and proves the virtue of top-dressing even on the richest natural pastures”

The Cattle King, Sir Sidney Kidman, visited Monomeith for both business and pleasure, another indication of how well known this property was.

In later years the property was again subdivided presumably between David’s two sons Michael and Hugh. Their descendants retained ownership until recently. Ironically after so many years in family hands, through three generations, we have discovered both the properties in advertisements in the real estate section of the Weekly Times.

Caldermeade was sold in 2016.

Through articles and advertisements for the property, in the local paper, we discovered more family history. For instance, only four years ago, there was an article in the Pakenham Gazette about Brian Bourke, the then owner of Caldermeade.

A fall from a horse, broken bones and 32 hours lying in a paddock would spell disaster for most 77-year- olds, but Hughie Bourke comes from tough stock. Fearing the worst, family and friends rallied together last week to rescue the stricken grandfather after he was reported missing last Thursday. Now recovering in The Alfred hospital with a shattered femur and pelvis, Hughie reckons he spent his marathon ordeal enjoying the company of animals on his Caldermeade property, but was disappointed to miss the day’s horse racing. Falling from his horse, he remained injured on the ground for almost a day and a half, watching the changing sky and surrounded by foxes and cattle. And while “the old cockie” has a long road to recovery ahead, he told his kids that it was a “bloody beaut” watching the clouds go down and sleeping next to the animals on his farm.”

Monomeith is on the market at the time of this post, July 2017, thus ending three generations of Bourkes running cattle on this property. An article published in the Pakenham Gazette describes the property:

‘Monomeith is heritage listed by the Shire of Cardinia because the house, which was built about 1899, and trees represent a long-term farming enterprise carried out by one family.

The old woolshed, and early picket fences and gateways that survive along the frontage and in some of the paddocks are a reminder of times gone by.

The large double-fronted weatherboard verandah farm house has been home to the Bourke family for more than a century.’

Margaret was the twelfth child of Michael and Catherine. We do not know the exact date of her birth but we know she married Robert Massey Coote in 1883. In 1886, in partnership with Lance Herbert the Cootes established a store and transport business in Orbost. They had three children. Robert died in 1891, and Margaret in 1935.

Agnes’ birth date is also unknown, but we know a little about her life. She married George Fraser of Aberdeen, Scotland. The family lived first in Nar Nar Goon and then in Aukland, New Zealand. They had six children, three born in Australia, and three in New Zealand.

Richard is the next child, but he died in infancy

Cecelia (Cissy) was Michael and Catherine’s fifteenth and youngest child. She never married.

The original Pakenham Post Office opened on 1 February 1859, with Michael as the postmaster. Catherine took over when Michael died in 1877, and Cissy took over from her, serving for many years. The history of Pakenham Post Offices is a bit garbled because, once the railway station opened, in 1977, there were two. Post Mistress was an important official role. For instance Cecelia’s name appears in 1909in the official Federal Gazette as the Electoral Registrar for Pakenham.

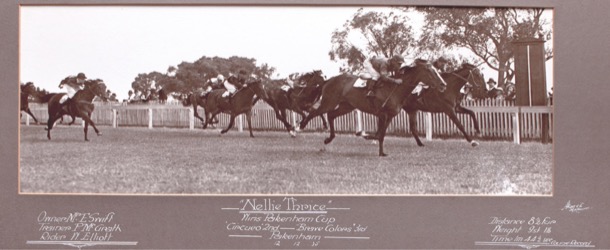

THE BOURKES : A RACING DYNASTY

From the early days at Bourke's hotel, Michael showed an interest in horse racing. We have no idea if this interest arose in the colony, where impromptu race meetings were common, or whether the interest came with him from Ireland. As Ireland has such a long and rich history of horse racing, this is quite likely.

Records show, that Michael and Catherine lent the paddock behind their hotel for the first race day picnics at Pakenham. This area was later named Racecourse Road. With great enthusiasm and involvement from Michael and his sons, racing flourished and in 1875 the Pakenham Racing Club was formed. Michael’s sons continued the family involvement, guiding the development of the club after Michael’s death in 1877.

Our direct descendant Michael, fourth son, left Pakenham for a law career in Melbourne. The rest of the family that remained in Pakenham continued to build a racing legacy.

David Bourke, the youngest son and owner of Monomeith Park, was a particularly good horseman and it is his line that continued the public involvement in racing through to the present day. David helped the Club to prosper in the early days, making his back paddock available for race meetings. This area was later named Racecourse Road, and was the site of the Pakenham Racing Club until 2014.

In the 1900’s the club fell into semi obscurity.and the Bourkes once more became involved in response to:

‘a letter from a local policeman to the Chief Secretary’s Office prompted an official letter being sent to the Pakenham Secretary Mr. A. L. Fairburn, requesting action be taken to rectify the situation.’

Hugh and Michael Bourke, David’s sons, came to the rescue, raising 4,000 pounds to reconstruct the course. The course was seven furlongs, 54ft. (1424m) in circumference.

After David’s death it was his sons Hugh and Michael who played the crucial role of keeping the club alive and it continued to hold picnic race meetings. The land was leased to the club by the Bourkes for no fee on condition that profits were spent on public amenities.Finally despite pressure for the site to become Crown land,the Bourkes agreed to sell the track to the Pakenham Racing Club for 25 000 pounds ($50 000). The deal was finalised in 1957.

"It was about a quarter of what it was worth,but back then our family wanted it to stay a racetrack forever and we always thought it would, " Hughie Bourke is quoted as saying.

The Bourkes maintained their interest in the club after the sale, serving on the committee and fulfilling other roles. Michael, David and Gavan held the position of Secretary between the years 1926 and 1999. A number of other family members also served on the committee for lengthy periods of time.

Early this century as the suburban sprawl reached Pakenham the racing club committee decided to sell the land and use the considerable profits to redevelop a new racing track at Tynong on a site of 246 hectares. In February 2014 the cub hosted the last race meeting at the old site and at the time, Gavan Bourke commented that it was sad that the old track,on a 27 hectare site had been sold for redevelopment to accomodate the urban sprawl.

The Bourke family interest in racing is also evident in positions held within the Victorian Racing Club [VRC] by David’s direct descendants.

David Bourke [1930-2005] David’s grandson, was a racing administrator for 60 years. He began his career after his father’s death when aged 19 he took over as Secretary of the Pakenham Racing Club.

He served on the VRC committee for twenty years, seven years, as Chairman. In this role he presided over the nation's most famous race, the Melbourne Cup from 1991 until 1998. The David Bourke Provincial Plate is run annually in June at Flemington, the Saturday of the Queen's Birthday weekend.

David’s brother John, also had a career in the thoroughbred racing industry. He was employed by the VRC as the Veterinary Steward. During a long and distinguished career he was instrumental in the introduction of drug testing of thoroughbreds. Dr Bourke went on to become a world authority on equine medicine and the use and effect of drugs on horses.

So from the first race meeting in Pakenham, in the early days of the Colony of Victoria, Michael’s and Catherine’s descendants have been involved in the horse racing industry. Some, such as our line, have had a recreational interest in horse racing whereas others, such as David’s line, produced several Bourkes who made their careers in thoroughbred racing. Quite a family affair through the generations!

Pakenham, the visit

So, in May 2017, one hundred and seventy-three years after our great, great, grandparents Catherine and Michael Bourke selected Minton’s Creek Run, we stood on the very spot. In 1844 the area was probably grassy woodland, open country, well grassed and with shade for the cattle. Like in so much of Victoria, the early settlers, our great, great grandparents amongst them, could just take possession and let their stock loose. Today the area is still a pastoral landscape but obviously broken into smaller holdings. Minton’s Run appears to be quite hilly, rising from the creek to the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges in the North, and undulating to hilly country in the East and the West.

It must have been a hard life. The day we were there was cold, and after recent rain the ground was soft and muddy. Not much fun carrying water from the creek in this weather. Presumably Michael and Catherine’s bark hut would have been near this water source but up on the hill a little, safe from floods and away from the soggy creek flats. We walked a little way along the dirt road imagining Michael and Catherine building their bark hut, collecting water from the creek and tending their stock.