Billy Goat Hill

Are You Related to the McCormacks?

08 11 23 14:24 Filed in: Jim

Over the years Sue and I have been writing our family stories, we have developed our own little tradition of excursions. We spent a day at Croydon visiting our mother’s childhood haunts; we parked outside our own childhood home and retraced our walk to school; and we spent a day driving between the Pakenham Bourke’s properties.

Now, after months of piecing together the McCormack and Hamilton backgrounds, marvelling at the story of three McCormack boys marrying three Hamilton girls, we were going to visit the actual sites. Very conveniently, we could stay at Sue and Jono’s property nearby. We roughed out an itinerary, and a food and wine list. The forecast was dubious, but we would mostly be in the car. Jono offered himself as designated driver.

On the first morning, we pulled into Molesworth, familiar as the second last town before Sue and Jono’s road. I looked at the hall, right on the main road. We took pictures, and peered in the dirty windows.

It wasn’t until I walked down the side of the building that the significance of it all hit me. There, on a hill behind the town strip, sat Balham Hill, the red brick house our grandmother grew up in. Her father had donated the land for the hall. We noted that the hill was much too steep for young ladies to navigate.

The right turn into Whanregarwen Road was very near. We parked in the clearing next to the Rail Trail, and Sue and I climbed a rough cutting until we could see Balham Hill again, in its home paddock.

We turned to look out across the river to the hills beyond. What a view they had had. Not even the great 1870 flood would have reached the house perched right up there. And how close to the homestead the train line had been! The twice daily trains would have made their presence felt.

I thought about Grace, our grandmother growing up here, in this grand house, going to primary school in Molesworth, a short walk away. Her father, John, was an important man in the district, a Justice of the Peace and on the Yea council. When Grace was seven, the house had been extended and rebuilt.

A little further on we came across Balham Hill’s proper driveway, and a different view of the house. With her knowledgable eye, Sue noted the quality of the the land itself, and of the farming techniques, where many trees were left in the pastures.

With an eye on Google Maps, we drove on. The property up the road a bit had belonged to the previous generation: our great, great grandparents, James and Bridget Hamilton. We knew that they had selected the property, “Cremona” estate, 1220 acres, in 1866. It was “situated on the southern concave side of a great sweeping arc of the Goulburn River … rising to high ground in the south where it fronts the Whanregarwen Road.”

The "great sweeping arc” is still there, in spite of 150 years of floods and droughts. It means that the river leaves Whanregarwen Road at right angles. We stopped at that spot, looking out over the river flats. “This would have been Cremona land”, said Sue.

A farm bike pulled up alongside us. We can’t remember exactly what the man said, but it was something like “Can I help you?” but tinged with suspicion. As we wound down our windows, I thought of Chris’s quip about being ready to bail us out when we were picked up for loitering

After some explanations, Jono mentioned his and Sue’s nearby property on the Gobur Road, and it emerged that this young man, Matt Ridd, owned the business, Murrindindi Kitchens, who had put in their kitchen. The atmosphere warmed immediately, and Matt told us what he remembered of the old house at Cremona. His family, too, went back many generations in that area.

He was full of stories. The old house was gone before he was born, but he used to play around there, by the area known as the “old Cremona Drive”, where there were old bricks and things. There was an old brick lined well, down near the river, full of snakes. There had been a communal sheep wash at Balham Hill. We drank it all in eagerly.

Eventually he turned his bike around and led us up the road, around the corner to an unmarked farm gate. We took photos, and pointed to twin lines of deciduous trees that could well have flanked Cremona’s driveway.

Off in the distance the river seemed a long way down. We had read the story of the 1870 flood surrounding and isolating the original house, and of James rescuing the family in the middle of the night, by crossing a flooded creek with horse and dray. Afterwards he rebuilt the house on much higher ground. Matt left us and we drove off in the other direction towards Alexandra.

As we drove, I pictured James driving his family to Sunday Mass along this road. The story goes that he would hurry up his daughters, complaining that his “Presbyterian horses couldn’t wait all day for lazy Catholics.”

The winding road down the hill into Alexandra from Cremona, is a familiar route for Jono and me. As we arrived in Alexandra, we were looking at the town with different eyes. We passed the impressive Shire Hall and Library and wondered whether any of the Hamiltons had graced the steps of either building. Charles Hamilton, James’s only son, and heir to Cremona was Shire president three times, so he may have even been involved in their creation.

The people with the answers are now in Alexandra Cemetery, our next destination.

We easily found the Catholic section with its assortment of Celtic Crosses, the tallest belonging to Charles’s wife Hannah, who died quite young, leaving two young children and a baby.

We did not find Charles or his parents in this section, so we decided to have Margaret’s salad rolls and a cup of tea in the sun and continue the search after lunch.

In the Protestant section, we did find more Hamiltons. Agnes, James’s mother, who emigrated with him, and James himself is also on the headstone. You may remember from our previous post, that they were both Protestants. Very fitting and buried in the correct section. Buried with them, is Brigid, who chose not to be buried in the Catholic section but here with her husband and mother in law. Their daughter Sara, who died at twenty-three, is also buried here. We did not find Charles although we do know he is buried at Alexandra too. Our excuse is that this was our first graveyard and we were not yet expert headstone hunters. I will return on my next trip into Alex with my new found expertise.

That night, in front of the fire at Sue and Jono’s house, as Jono cooked our Spanikopita dinner, Sue and I poured over our notes. I opened up and reread the 2006 article we had found in the journal “Eureka Street”, where Peter Hamilton, great grandson of the original Hamiltons of Cremona, describes his own visit to Alexandra cemetery, and the site of Cremona. Right there, in the article, was the name Les Ridd.

Matt Ridd, perched on his motorbike on the side of Whanregarwen Road, had described his dad’s recent illness, and here was a story about him taking Peter around Cremona in 2005.

Matt had given Sue his mobile number, and she texted him the link. Matt immediately rang back. Sue and Matt shared more stories. It was exciting to find that real world link with our past.

Later, on the strength of our interaction with Matt, I reached out to Peter Hamilton, author of the article. More about that in a later post.

The next morning, our first destination was Landscape at Tallarook. As we drove via Yea on the same route the young Hamilton girls would have taken, we again wondered how the three young ladies travelled to the Tallarook railhead and how long it took them. It took us fifty minutes on a good bitumen road.

Originally John McCormack Snr, of Red Barn, had bought the property, then called Tallarook House. Some of his sons had lived there, and, eventually one of them, James, became its long term owner.

After they were married, James and Grace changed the name of the property from Tallarook House to ‘Landscape.’ Archbishop Little in his small family history waxes lyrical about the property and the life there.

…….’Landscape’ a more fitting name for the unique and pleasant vistas of scenery viewed from its open wide verandahs.

After settling in at “Landscape”, husband and wife took a prominent part in the social, civic, charitable ,religious, and sporting life of the community and continued to do so throughout their lives. Landscape with its gracious hostess was a perfect setting…….

It is still is a beautiful, prime pastoral property. When it sold most recently in 2017, as a much reduced holding, it still boasted three kilometres of Goulburn River frontage.

Landscape today still looks very much the gracious country house. It still sits amidst a cluster of small houses and large stone stables. The lovely old house overlooks the Goulburn and is set in a large well tended garden dominated by old stately trees. We wondered if James and Grace had planted the trees.

We wanted to stop and have a really good look, but the security cameras and the gentleman trimming the hedge were a little off putting. We settled for another drive past. On one side of the house Landscape now has its own vineyard, a more recent addition we think. Not so Tennis Court Paddock, on the other side of the house. No longer a tennis court, but we could imagine in days past it would have been a well used addition.

It was a short drive from Landscape to Tallarook. The old railway line, now a rail trail, had followed the road. It culminated in the Tallarook Railway Station, which is still in operation, on the main Melbourne to Sydney line. Back when James McCormack was establishing himself in the district, it was the railhead. Although much reduced in capacity and importance, it still has the feeling of a substantial, permanent structure. What had been high wide doors have been bricked in. There are a few historical signs, but it was hard to get a sense of the bustling, smelly, noisy place it once would have been. We took photos and moved on.

We drove into the grassy grounds of St Joseph’s. There is very little information about this church. It was blessed in July 3rd 1887 by Archbishop Carr.

It is sad to realise that this beautiful bluestone building is now virtually unused. It is not listed on the Diocese website.

Jono had sent an email to the Seymour parish priest the day before, in the hope that we might get a peek inside, but there was no reply.

The slate roof looked sound, and all the windows were intact, thanks to heavy wire screens on the outside of them. Archbishop Little tells us that “The memory of Grace and James McCormack has been retained in the Catholic community of Tallarook by the erection in St. Joseph's Church of ornate stained glass windows…”

We couldn’t really see the windows very well from the outside, but they looked substantial.

The only other buildings on the block were two little ramshackle outdoor dunnies, tucked under the trees on the outskirts of the cleared area.”

James and Grace had been dominating our thoughts in Tallarook, and now we drove on the the Seymour cemetery to find their graves.

Far from finding a quiet country cemetery, we found ourselves over the road from the busy midweek races at the Seymour Racetrack. Dodging horse floats, we turned right and parked in the cemetery grounds. We huddled quietly by the car, hoping that we weren’t intruding on a funeral still in progress. The land around Seymour is dry and stony, and heavy grey skies reminded us that rain had been forecast.

The sections in the cemetery were clearly labelled, and we headed toward the forest of Celtic Crosses in the Catholic section.

There were McCormacks everywhere. But the largest marble Celtic cross marked the graves of Grace, aged 56 and James JP (Justin of the Peace), aged 78.

We drove through Seymour. I tried to see it as it had been when James was president of the Council, but the church has been rebuilt, the town has grown, and the sad, unkempt, crowded together little houses and struggling small businesses overpower any sense of history.

Rain was still threatening, and the wind was cold, as we pulled up at the Tourist Park alongside the river in Euroa. Parked a few cars away, was Janet, who Sue and Jono knew from Trust for Nature. Janet is a local landowner, active in all local environmental organisations and activities. She was cleaning up, after running a morning water-quality training session in the river.

When we explained our mission, she exclaimed, in her larger-than-life voice,

“Oh! Are you related to the McCormacks?”

“Yes, our grandmother was a McCormack.”

It felt real. We did belong to these people: men who had dominated four local councils and been part of all the important local infrastructure decisions for the second half of the nineteenth century, and the beginning of the twentieth. Families whose weddings were written up in the local papers, whose names were on the stained glass windows in the churches, whose memorials dominated the cemeteries.

We ate our egg sandwiches and drank tea from the thermos huddled in a shelter by the river. Euroa felt older, more solid and prosperous than Seymour.

The Euroa McCormack was Thomas, the eldest of John and Jane’s children, born at Red Barn in Beveridge. We hadn’t spent much time exploring Thomas’s story, because we had been so taken by the romance of his younger brothers, James, John and Michael who had married the three Hamilton sisters. But here, in Euroa, it felt important to fit him into the story.

We had a few notes, (and a bit of subsequent expert input, to be explained later) and spent a bit of time pulling his story together.

Thomas was the eldest son of John and Jane McCormack of Red Barn Beveridge. He was born in 1851.

After living with his brothers James and Michael at Landscape, Thomas purchased a property in Mooroopna, near Shepparton, in 1882.

The property was called “The Desert”, and was in Toolamba Road. Like the other family properties, Thomas’s was along the Goulburn River, but much further north.

Soon after moving to Mooroopna, Thomas married Bridget Agnes Cooke, of Pyalong. There’s more to find our about this, but we think that Bridget’s brother John might have also invested in this property. Over time, it seems that the property developed into a “fine property” called May Park Estate.

Thomas and Bridget were active community members. In particular, Thomas was very involved with the Mooroopna Hospital Board. They had four sons and two daughters.

In 1908, Thomas and Bridget sold up in Mooroopna and bought “Springside” in Gooram, near Euroa. Thomas was 57, and Bridget, 55. It seems they immediately became involved in their new community.

In 1912, Bridget became sick with colon cancer. After a difficult two years, she died. She was 61.

Thomas remarried two years later, in 1916. We don’t know much about his second wife, Elizabeth. She was the daughter of Patrick and Elizabeth O’Connor of “Parkview”, Kilmore.

Then, in 1918, further tragedy struck. Daughter Mary, who lived with Thomas and Elizabeth at Gooram, died, aged thirty.

We can only speculate about Thomas’s motives, but, quite soon, he sold up and they moved into town. His new house was “Marengo” in Anderson St.

Thomas and Elizabeth had thirteen years together. It seems they built a busy, community-focussed life in Euroa. Among other things, Thomas was involved in the District Racing Club, the Agricultural Society, the Band, the Swimming Club and the Bush Nursing Hospital.

Thomas died in 1929, aged 78.

Elizabeth, who is buried alongside him in Euroa, lived in Hawthorn for a further fourteen years. She died in 1943.

Euroa Cemetery, like Seymour Cemetery, is in a rather uninspiring location. Separated from the town by the Hume Freeway, it sits amongst flat empty paddocks.

It was still cold and raining a little, as we approached the rows of graves, looking for the Catholic section and the telltale sign of the Celtic Crosses. Well practised now, we headed for the tallest cross.

Sure enough, we found the McCormack’s lichen encrusted, but still readable, very large granite Celtic Cross. Buried here are Thomas McCormack and Brigid, his first wife, and mother of his children, who died fourteen years before him. Only four years later, Mary their daughter also died, and is buried with her parents. Many years later, in 1943, Elizabeth, Thomas’s second wife, was also interred in this plot. She had lived in Hawthorn after Thomas’s death, but chose to be buried here with him.

We were also fascinated to see, crowded in next to the McCormack plot, the priests and nuns of Euroa. Notably, the nuns' graves were a little smaller.

Having found Thomas’s grave we set off to find his property, Springside, at Gooram.

We drove into the Strathbogie Ranges on the beautiful Euroa-Merton Road for seventeen kilometres, and then turned right, onto a long straight road that followed the valley.

It was a lovely tree-lined road with only one or two properties along it. It seemed very remote to us. What must it have been like when Thomas and Brigid lived here?

The first indication that we were there, was a large new sign, ‘Springside’ at the beginning of a long drive that disappeared over the hill.

Of great interest though was the very large Banksia marginata on the road verge, right opposite the gate. There are very few original Banksia marginata left in the Strathbogie Ranges, and we had never seen such a large one. We wondered how old it was and if it had been growing there, as Thomas and family drove and rode past.

As no house was obvious here, we drove on. Almost at the end of the road, there was the house, sitting quietly in its old garden. It is not as grand a house as Landscape, but it looks substantial and comfortable. Thomas’s white, weatherboard house is surrounded on three sides by a wide verandah and we could imagine Thomas sitting on the verandah, looking across the lush paddocks to the distant hills, fires roaring in the fireplaces inside. It was certainly a lovely spot.

Our last day of graveyard hopping dawned cold and wet again. Very appropriate and atmospheric weather, and Yea Cemetery did not disappoint.

The old cemetery, surrounded by bushland, was tucked away on the hill, behind Yea township. The newer section of the cemetery, lies bland, uninteresting and uninspiring, out of sight.

Unlike all the other cemeteries that have been in flat and open expanses, Yea is set in a hilly spot. We arrived and walked up the small, treed hill, looking once again for the Catholic section. Not as many Celtic Crosses to guide us here and no clear signage. Near the top of the hill we began to see the Irish surnames, so the hunt for our great grandparents began in earnest. It was raining more heavily now, and we thought we were to be disappointed, but Jono saved the day.

Not a Celtic Cross, but a large impressive slab, with all that we sought buried here. It was sobering to think that our grandmother, Grace had stood here, as the bodies of John and Joan (previously called Johanna) McCormack, her parents, were interred. Maybe our father as a four year old child had been there too.

Also on the stone were John’s and Joan’s infant son Aloysius who died aged ten months and Cyril, Grace’s brother and his wife Judith. Quite a family plot.

What a beautiful little cemetery in which to end our journey around Central Victoria and how fitting to end it with the resting place of our great grandparents.

Now, after months of piecing together the McCormack and Hamilton backgrounds, marvelling at the story of three McCormack boys marrying three Hamilton girls, we were going to visit the actual sites. Very conveniently, we could stay at Sue and Jono’s property nearby. We roughed out an itinerary, and a food and wine list. The forecast was dubious, but we would mostly be in the car. Jono offered himself as designated driver.

On the first morning, we pulled into Molesworth, familiar as the second last town before Sue and Jono’s road. I looked at the hall, right on the main road. We took pictures, and peered in the dirty windows.

It wasn’t until I walked down the side of the building that the significance of it all hit me. There, on a hill behind the town strip, sat Balham Hill, the red brick house our grandmother grew up in. Her father had donated the land for the hall. We noted that the hill was much too steep for young ladies to navigate.

The right turn into Whanregarwen Road was very near. We parked in the clearing next to the Rail Trail, and Sue and I climbed a rough cutting until we could see Balham Hill again, in its home paddock.

We turned to look out across the river to the hills beyond. What a view they had had. Not even the great 1870 flood would have reached the house perched right up there. And how close to the homestead the train line had been! The twice daily trains would have made their presence felt.

I thought about Grace, our grandmother growing up here, in this grand house, going to primary school in Molesworth, a short walk away. Her father, John, was an important man in the district, a Justice of the Peace and on the Yea council. When Grace was seven, the house had been extended and rebuilt.

A little further on we came across Balham Hill’s proper driveway, and a different view of the house. With her knowledgable eye, Sue noted the quality of the the land itself, and of the farming techniques, where many trees were left in the pastures.

With an eye on Google Maps, we drove on. The property up the road a bit had belonged to the previous generation: our great, great grandparents, James and Bridget Hamilton. We knew that they had selected the property, “Cremona” estate, 1220 acres, in 1866. It was “situated on the southern concave side of a great sweeping arc of the Goulburn River … rising to high ground in the south where it fronts the Whanregarwen Road.”

The "great sweeping arc” is still there, in spite of 150 years of floods and droughts. It means that the river leaves Whanregarwen Road at right angles. We stopped at that spot, looking out over the river flats. “This would have been Cremona land”, said Sue.

A farm bike pulled up alongside us. We can’t remember exactly what the man said, but it was something like “Can I help you?” but tinged with suspicion. As we wound down our windows, I thought of Chris’s quip about being ready to bail us out when we were picked up for loitering

After some explanations, Jono mentioned his and Sue’s nearby property on the Gobur Road, and it emerged that this young man, Matt Ridd, owned the business, Murrindindi Kitchens, who had put in their kitchen. The atmosphere warmed immediately, and Matt told us what he remembered of the old house at Cremona. His family, too, went back many generations in that area.

He was full of stories. The old house was gone before he was born, but he used to play around there, by the area known as the “old Cremona Drive”, where there were old bricks and things. There was an old brick lined well, down near the river, full of snakes. There had been a communal sheep wash at Balham Hill. We drank it all in eagerly.

Eventually he turned his bike around and led us up the road, around the corner to an unmarked farm gate. We took photos, and pointed to twin lines of deciduous trees that could well have flanked Cremona’s driveway.

Off in the distance the river seemed a long way down. We had read the story of the 1870 flood surrounding and isolating the original house, and of James rescuing the family in the middle of the night, by crossing a flooded creek with horse and dray. Afterwards he rebuilt the house on much higher ground. Matt left us and we drove off in the other direction towards Alexandra.

As we drove, I pictured James driving his family to Sunday Mass along this road. The story goes that he would hurry up his daughters, complaining that his “Presbyterian horses couldn’t wait all day for lazy Catholics.”

The winding road down the hill into Alexandra from Cremona, is a familiar route for Jono and me. As we arrived in Alexandra, we were looking at the town with different eyes. We passed the impressive Shire Hall and Library and wondered whether any of the Hamiltons had graced the steps of either building. Charles Hamilton, James’s only son, and heir to Cremona was Shire president three times, so he may have even been involved in their creation.

The people with the answers are now in Alexandra Cemetery, our next destination.

We easily found the Catholic section with its assortment of Celtic Crosses, the tallest belonging to Charles’s wife Hannah, who died quite young, leaving two young children and a baby.

We did not find Charles or his parents in this section, so we decided to have Margaret’s salad rolls and a cup of tea in the sun and continue the search after lunch.

In the Protestant section, we did find more Hamiltons. Agnes, James’s mother, who emigrated with him, and James himself is also on the headstone. You may remember from our previous post, that they were both Protestants. Very fitting and buried in the correct section. Buried with them, is Brigid, who chose not to be buried in the Catholic section but here with her husband and mother in law. Their daughter Sara, who died at twenty-three, is also buried here. We did not find Charles although we do know he is buried at Alexandra too. Our excuse is that this was our first graveyard and we were not yet expert headstone hunters. I will return on my next trip into Alex with my new found expertise.

That night, in front of the fire at Sue and Jono’s house, as Jono cooked our Spanikopita dinner, Sue and I poured over our notes. I opened up and reread the 2006 article we had found in the journal “Eureka Street”, where Peter Hamilton, great grandson of the original Hamiltons of Cremona, describes his own visit to Alexandra cemetery, and the site of Cremona. Right there, in the article, was the name Les Ridd.

Matt Ridd, perched on his motorbike on the side of Whanregarwen Road, had described his dad’s recent illness, and here was a story about him taking Peter around Cremona in 2005.

Matt had given Sue his mobile number, and she texted him the link. Matt immediately rang back. Sue and Matt shared more stories. It was exciting to find that real world link with our past.

Later, on the strength of our interaction with Matt, I reached out to Peter Hamilton, author of the article. More about that in a later post.

The next morning, our first destination was Landscape at Tallarook. As we drove via Yea on the same route the young Hamilton girls would have taken, we again wondered how the three young ladies travelled to the Tallarook railhead and how long it took them. It took us fifty minutes on a good bitumen road.

Originally John McCormack Snr, of Red Barn, had bought the property, then called Tallarook House. Some of his sons had lived there, and, eventually one of them, James, became its long term owner.

After they were married, James and Grace changed the name of the property from Tallarook House to ‘Landscape.’ Archbishop Little in his small family history waxes lyrical about the property and the life there.

…….’Landscape’ a more fitting name for the unique and pleasant vistas of scenery viewed from its open wide verandahs.

After settling in at “Landscape”, husband and wife took a prominent part in the social, civic, charitable ,religious, and sporting life of the community and continued to do so throughout their lives. Landscape with its gracious hostess was a perfect setting…….

It is still is a beautiful, prime pastoral property. When it sold most recently in 2017, as a much reduced holding, it still boasted three kilometres of Goulburn River frontage.

Landscape today still looks very much the gracious country house. It still sits amidst a cluster of small houses and large stone stables. The lovely old house overlooks the Goulburn and is set in a large well tended garden dominated by old stately trees. We wondered if James and Grace had planted the trees.

We wanted to stop and have a really good look, but the security cameras and the gentleman trimming the hedge were a little off putting. We settled for another drive past. On one side of the house Landscape now has its own vineyard, a more recent addition we think. Not so Tennis Court Paddock, on the other side of the house. No longer a tennis court, but we could imagine in days past it would have been a well used addition.

It was a short drive from Landscape to Tallarook. The old railway line, now a rail trail, had followed the road. It culminated in the Tallarook Railway Station, which is still in operation, on the main Melbourne to Sydney line. Back when James McCormack was establishing himself in the district, it was the railhead. Although much reduced in capacity and importance, it still has the feeling of a substantial, permanent structure. What had been high wide doors have been bricked in. There are a few historical signs, but it was hard to get a sense of the bustling, smelly, noisy place it once would have been. We took photos and moved on.

We drove into the grassy grounds of St Joseph’s. There is very little information about this church. It was blessed in July 3rd 1887 by Archbishop Carr.

It is sad to realise that this beautiful bluestone building is now virtually unused. It is not listed on the Diocese website.

Jono had sent an email to the Seymour parish priest the day before, in the hope that we might get a peek inside, but there was no reply.

The slate roof looked sound, and all the windows were intact, thanks to heavy wire screens on the outside of them. Archbishop Little tells us that “The memory of Grace and James McCormack has been retained in the Catholic community of Tallarook by the erection in St. Joseph's Church of ornate stained glass windows…”

We couldn’t really see the windows very well from the outside, but they looked substantial.

The only other buildings on the block were two little ramshackle outdoor dunnies, tucked under the trees on the outskirts of the cleared area.”

James and Grace had been dominating our thoughts in Tallarook, and now we drove on the the Seymour cemetery to find their graves.

Far from finding a quiet country cemetery, we found ourselves over the road from the busy midweek races at the Seymour Racetrack. Dodging horse floats, we turned right and parked in the cemetery grounds. We huddled quietly by the car, hoping that we weren’t intruding on a funeral still in progress. The land around Seymour is dry and stony, and heavy grey skies reminded us that rain had been forecast.

The sections in the cemetery were clearly labelled, and we headed toward the forest of Celtic Crosses in the Catholic section.

There were McCormacks everywhere. But the largest marble Celtic cross marked the graves of Grace, aged 56 and James JP (Justin of the Peace), aged 78.

We drove through Seymour. I tried to see it as it had been when James was president of the Council, but the church has been rebuilt, the town has grown, and the sad, unkempt, crowded together little houses and struggling small businesses overpower any sense of history.

Rain was still threatening, and the wind was cold, as we pulled up at the Tourist Park alongside the river in Euroa. Parked a few cars away, was Janet, who Sue and Jono knew from Trust for Nature. Janet is a local landowner, active in all local environmental organisations and activities. She was cleaning up, after running a morning water-quality training session in the river.

When we explained our mission, she exclaimed, in her larger-than-life voice,

“Oh! Are you related to the McCormacks?”

“Yes, our grandmother was a McCormack.”

It felt real. We did belong to these people: men who had dominated four local councils and been part of all the important local infrastructure decisions for the second half of the nineteenth century, and the beginning of the twentieth. Families whose weddings were written up in the local papers, whose names were on the stained glass windows in the churches, whose memorials dominated the cemeteries.

We ate our egg sandwiches and drank tea from the thermos huddled in a shelter by the river. Euroa felt older, more solid and prosperous than Seymour.

The Euroa McCormack was Thomas, the eldest of John and Jane’s children, born at Red Barn in Beveridge. We hadn’t spent much time exploring Thomas’s story, because we had been so taken by the romance of his younger brothers, James, John and Michael who had married the three Hamilton sisters. But here, in Euroa, it felt important to fit him into the story.

We had a few notes, (and a bit of subsequent expert input, to be explained later) and spent a bit of time pulling his story together.

Thomas was the eldest son of John and Jane McCormack of Red Barn Beveridge. He was born in 1851.

After living with his brothers James and Michael at Landscape, Thomas purchased a property in Mooroopna, near Shepparton, in 1882.

The property was called “The Desert”, and was in Toolamba Road. Like the other family properties, Thomas’s was along the Goulburn River, but much further north.

Soon after moving to Mooroopna, Thomas married Bridget Agnes Cooke, of Pyalong. There’s more to find our about this, but we think that Bridget’s brother John might have also invested in this property. Over time, it seems that the property developed into a “fine property” called May Park Estate.

Thomas and Bridget were active community members. In particular, Thomas was very involved with the Mooroopna Hospital Board. They had four sons and two daughters.

In 1908, Thomas and Bridget sold up in Mooroopna and bought “Springside” in Gooram, near Euroa. Thomas was 57, and Bridget, 55. It seems they immediately became involved in their new community.

In 1912, Bridget became sick with colon cancer. After a difficult two years, she died. She was 61.

Thomas remarried two years later, in 1916. We don’t know much about his second wife, Elizabeth. She was the daughter of Patrick and Elizabeth O’Connor of “Parkview”, Kilmore.

Then, in 1918, further tragedy struck. Daughter Mary, who lived with Thomas and Elizabeth at Gooram, died, aged thirty.

We can only speculate about Thomas’s motives, but, quite soon, he sold up and they moved into town. His new house was “Marengo” in Anderson St.

Thomas and Elizabeth had thirteen years together. It seems they built a busy, community-focussed life in Euroa. Among other things, Thomas was involved in the District Racing Club, the Agricultural Society, the Band, the Swimming Club and the Bush Nursing Hospital.

Thomas died in 1929, aged 78.

Elizabeth, who is buried alongside him in Euroa, lived in Hawthorn for a further fourteen years. She died in 1943.

Euroa Cemetery, like Seymour Cemetery, is in a rather uninspiring location. Separated from the town by the Hume Freeway, it sits amongst flat empty paddocks.

It was still cold and raining a little, as we approached the rows of graves, looking for the Catholic section and the telltale sign of the Celtic Crosses. Well practised now, we headed for the tallest cross.

Sure enough, we found the McCormack’s lichen encrusted, but still readable, very large granite Celtic Cross. Buried here are Thomas McCormack and Brigid, his first wife, and mother of his children, who died fourteen years before him. Only four years later, Mary their daughter also died, and is buried with her parents. Many years later, in 1943, Elizabeth, Thomas’s second wife, was also interred in this plot. She had lived in Hawthorn after Thomas’s death, but chose to be buried here with him.

We were also fascinated to see, crowded in next to the McCormack plot, the priests and nuns of Euroa. Notably, the nuns' graves were a little smaller.

Having found Thomas’s grave we set off to find his property, Springside, at Gooram.

We drove into the Strathbogie Ranges on the beautiful Euroa-Merton Road for seventeen kilometres, and then turned right, onto a long straight road that followed the valley.

It was a lovely tree-lined road with only one or two properties along it. It seemed very remote to us. What must it have been like when Thomas and Brigid lived here?

The first indication that we were there, was a large new sign, ‘Springside’ at the beginning of a long drive that disappeared over the hill.

Of great interest though was the very large Banksia marginata on the road verge, right opposite the gate. There are very few original Banksia marginata left in the Strathbogie Ranges, and we had never seen such a large one. We wondered how old it was and if it had been growing there, as Thomas and family drove and rode past.

As no house was obvious here, we drove on. Almost at the end of the road, there was the house, sitting quietly in its old garden. It is not as grand a house as Landscape, but it looks substantial and comfortable. Thomas’s white, weatherboard house is surrounded on three sides by a wide verandah and we could imagine Thomas sitting on the verandah, looking across the lush paddocks to the distant hills, fires roaring in the fireplaces inside. It was certainly a lovely spot.

Our last day of graveyard hopping dawned cold and wet again. Very appropriate and atmospheric weather, and Yea Cemetery did not disappoint.

The old cemetery, surrounded by bushland, was tucked away on the hill, behind Yea township. The newer section of the cemetery, lies bland, uninteresting and uninspiring, out of sight.

Unlike all the other cemeteries that have been in flat and open expanses, Yea is set in a hilly spot. We arrived and walked up the small, treed hill, looking once again for the Catholic section. Not as many Celtic Crosses to guide us here and no clear signage. Near the top of the hill we began to see the Irish surnames, so the hunt for our great grandparents began in earnest. It was raining more heavily now, and we thought we were to be disappointed, but Jono saved the day.

Not a Celtic Cross, but a large impressive slab, with all that we sought buried here. It was sobering to think that our grandmother, Grace had stood here, as the bodies of John and Joan (previously called Johanna) McCormack, her parents, were interred. Maybe our father as a four year old child had been there too.

Also on the stone were John’s and Joan’s infant son Aloysius who died aged ten months and Cyril, Grace’s brother and his wife Judith. Quite a family plot.

What a beautiful little cemetery in which to end our journey around Central Victoria and how fitting to end it with the resting place of our great grandparents.

Comments

The Year of Covid

30 03 21 13:53 Filed in: Other

Where were you when the world changed?

As we begin work on this new post, the first one since February, babies conceived during this plague year are being born. Their normal is a Covid normal. Masked faces, elbow bumps and social distancing have replaced hugs and smiles. They will not be expected to “soldier on” through their cold symptoms. Every one of their days has its “epidemiology”, spelled out in graphs and statistics.

Norman Swan, Medical Science journalist, elevated by the pandemic to superstar status, calls this period, as the world begins the slow process of mass immunisation, “the end of the beginning”. We watch with well worn trepidation. And as we do, it feels like an important time to remember the details, to look back at the milestones, to explore the changes.

THE BEGINNING

JANUARY 25 - MARCH 12

January 25 - First Australian case, Wuhan returnee

January 31 - Chinese returnees have to quarantine in a third country

February 11 - WHO names the novel coronavirus and its disease

February 27 - Travellers from China, Iran and Italy banned

March 2 - First Australian community transmission

March 8 - First Australian death

March 9 - Carey Grammar school closed - staff case

March 12 -WHO calls it a pandemic for the first time, Prime Minister announces first economic stimulus package. Australia has had 142 cases so far.

MARGARET'S STORY

January 2020 had begun for me in hospital, five days after my mastectomy. The East coast of Australia was on fire, and Thurra River camp was already gone by then. But for a cautious decision to cancel their booking, the family would have been evacuated from there, just before it burnt.

Just as my cool hospital room, with its expansive views, insulated me from the smoky, hot air outside, so my personal health crisis kept me from the full force of the terrible losses in Gippsland and New South Wales.

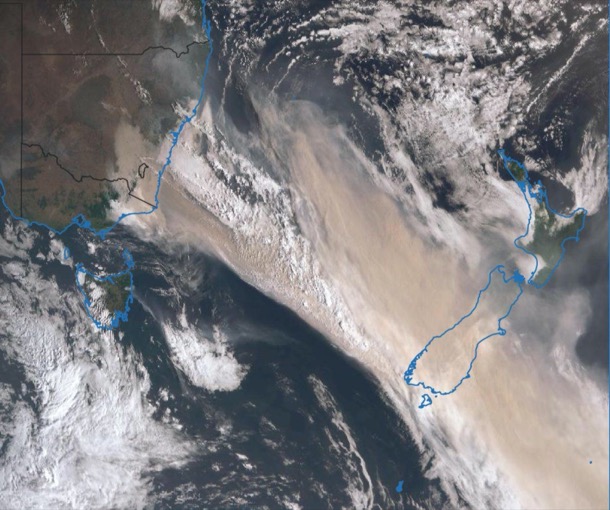

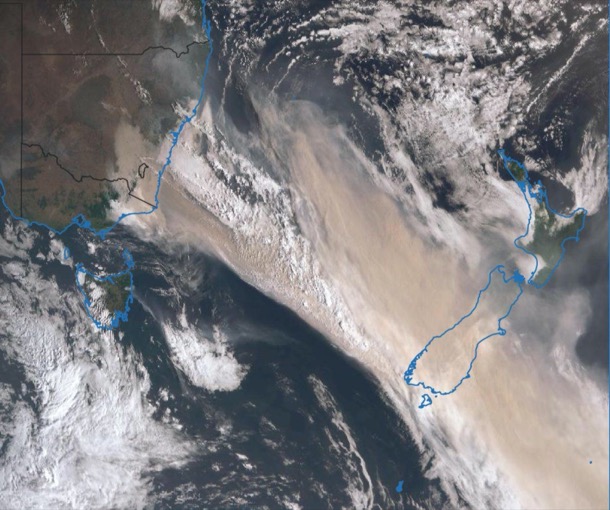

Smoke stretching to New Zealand

I planned to recover over January and be back into my busy life from the beginning of February. I would need a second operation, and had already begun to speculate on the least disruptive way to fit that into the months ahead.

News of a new virus from China was overshadowed by the antics of Trump and the horror of the fires. We heard from our friend Paul, the Point Hicks lighthouse keeper. He sent pictures from an unfamiliar burnt Thurra campground, and stories of sheltering in the lighthouse as the front approached. The first Australian Covid cases on January 25th hardly even caused a ripple in my world.

As February arrived, I felt my grand recovery plan was pretty much on track. I attended the first choir rehearsal, and Sue and I finalised the Recollections post we had begun in December. I was a little more tired than I had anticipated and I put off going back to singing lessons and to yoga. On February 7th I had a haircut. I had no way of knowing that it would be nine months before the next one.

Gradually, as the weeks passed and Autumn soothed the harshness of the Summer, my energy returned, and I began building back more fully. The first worrying Covid signs appeared: on March 2, there was the first Community transmission, and the first Victorian death on March 8. Nevertheless, I began Yoga classes, becoming more used to the lopsided feeling of a prosthetic left breast. The choir’s preparation for our Mikado season hotted up, and I spent lots of time matching costumes to singers, and practising my own part. Now those costumes are folded in boxes under my bed, as we tentatively plan a re-run in 2021.

The last regular engagement in my busy calendar was my weekly singing lesson. I made the arrangement to begin again on Tuesday March 10th, the day after the long weekend. On the Thursday we were all set to go to Bodhi’s twelfth birthday party.

That Tuesday, the WHO finally called it a pandemic and Dan Andrews, with Victorian cases at 36, set the first restrictions. Bodhi’s party was off, Singing lessons and Tuesday’s with Sue ended, and 2020 stretched ahead as a very different year.

THE BEGINNING - SUE'S STORY

By the time Margaret and I returned to our Tuesday routine in 2020 we had lived through a summer dominated by fire, grief, surgery and escalating concern about a virus in China.

In the weeks before Christmas, fires had ravaged much of NSW. Jono’s cousin Robert lost his house in the Blue Mountains and Sydney was covered in a pall of smoke, as mega blazes with towering flames devoured hectare after hectare of bush, destroying thousands and thousands of animals and hundreds of homes. We looked in horror at images of people huddled on beaches, as flames destroyed their town and firefighters were rendered powerless. Against this backdrop, in the week before Christmas, we were packing to go to Thurra. We began to have doubts: it was too dangerous. The bush was tinder dry after two years of drought in East Gippsland and the weather forecast was for hot, windy weather. After much deliberation and a family meeting at Thomas’, we collectively made the decision not to go! The kids were very disappointed, but to their credit, rallied, and began to plan what they could do instead. A week later, on January 31st, the Mallacoota fire roared through Croajingalong National Park, burning much of the park. Familiar places changed forever. Wingan Inlet, the Mueller Valley, the Thurra bridge and campground all gone.

Thurra River Campground after the fire

January, and the fires were still raging as a creeping concern about the spread of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan appeared in news commentary; (COVID-19) the disease, caused by "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2". These words were to become very familiar. On the January the 25th, we had a confirmed case of coronavirus in Melbourne, a returned Chinese citizen from Wuhan. This was the first case in Australia.

Three days later Anna was flying back from India via Singapore. We were very concerned that travellers from China would also be transiting through that transport hub. This is the first time I recall being concerned that the virus could infect a family member, or even someone I knew.

February, and Anna was back safely , the kids returned to school and the fire season continued, as the weather was hot and dry. Overseas, the news was alarming: news reports about escalating cases in China, Italy, Iran and on cruise ships. We began to learn more about how the virus spreads and how contagious it was. We closed our border to some foreign nationals, docking by cruise ships was restricted, and our neighbours cancelled their trip to India.

March, and Bodhi’s birthday on the 12th was cancelled! The consensus was: too many people and too risky in a small space. Jono and I went, vowing to socially distance. Unfamiliar with a behaviour that was to become second nature , we did not socially distance. That night, after discussion, we all decided that from now on birthday celebrations would need to at a safe distance and not inside. Little did we know that in 2020, Sara’s birthday in November, would be the only in-person celebration.

THE FIRST WAVE

MARCH 13 - MAY 11

KEY DATES

March 13 - 36 cases. National Cabinet formed.

March 15 - State of Emergency declared.First restrictions

March 19 - Ruby Princess disperses 2700 passengers around Australia

March 20 - Australia closes borders to non residents

March 22 - School holidays begin a week early. Run on toilet paper

March 30 - All Australian restrictions begin. Four reasons to leave home.

April 10 - Easter at home

April 15 - Home schooling begins

April 16 - Supermarkets introduce “old people’s hour”

April 27 - Massive ramp up in testing

May 5 - outbreak in Cedar Meats Abattoir and meat processing plant.

May 11- Some easing of restrictions

MARGARET'S STORY

During those few days, in that second week of March, there were many signs that things were hotting up, as case numbers reached thirty-six. We had scheduled a choir committee meeting before the next Monday night’s rehearsal, and emails shot round the committee.

By the time the Monday came around, Victoria was in its first day of “State of Emergency”. Only half our singers came. We insisted that everyone wash their hands, and we announced that we had decided to stop rehearsals until after Easter, but we went ahead and sang lustily. We knew nothing of aerosol spread. We had not yet heard about the Seattle choir, who, on March 10th also all washed their hands and sat a little further away from each other. Fifty-two of them were infected and two died.

It took another week before it really began to feel personal. We tut-tutted about the Ruby Princess debacle, though its real impact was yet to become clear. The Australian borders closed to tourists. But these things were just items on the News. The habit of listening to Dan Andrews live in Press Conferences began during this time. I remember sitting in the sun in the late morning, as he announced that school holidays were beginning a week early. My friend Laraine complained on Facebook that she had see people buying huge quantities of toilet rolls. We made jokes about it.

As the numbers of infected people in Australia climbed, the first frissons of alarm began. National Cabinet decided that all of Australia would restrict movement. This was the first time we heard the phrase “four reasons to leave home”, and “essential workers”.

We must have had some knowledge by then of infection rates. I remember waiting until fourteen days after Sage, our grandson, had had his last kinder session before we saw him. We poured over the legal document to see if we were allowed to call our visits “care”. I knitted him a “Bluey jumper”, listening to podcasts, filling in time.

Life became quieter. There were noticeably fewer cars on the roads. Easter came and went. It was the first Easter Sunday for a long time that we had not had lunch with Chris’s parents. We watched Andrea Bocelli sing Panis Angelicus and stroll out to gaze up the empty Milan streets.

Here is the Facebook Post I did on April13th:

As I listened this morning to Andrea Bocelli’s beautiful Easter offering in the empty Duomo in Milan, and watched the footage of empty streets in the world’s great cities, I felt a sense of loss and sadness that I had seen in others, but hadn’t yet felt myself.

The footage reminded me of “The last Time I Saw Paris”, a sad song written by Jerome Kern in 1940. It would be another five years before Paris was liberated.

The camera in Milan roamed over a packed city. All those lives on hold, cooped up little apartments!

In New York, the only sound in the streets is sirens.

But then there is this.....

People in the Punjab, blinking like creatures exiting a cave, look to the north and there, hundreds of kilometres away are the white Himalayas. They have been hidden by pollution for decades.

Factory and vehicle emissions have dropped in China so much that two months worth of pollution reduction “likely has saved the lives of 4,000 kids under 5 and 73,000 adults over 70.”

According to The Climate Group, working from home has the potential to reduce over 300 MILLION tonnes of carbon emissions per year, and surely we will see a lot of that even after the lockdown. And there are stories of animals reclaiming the empty streets all over the world.

I downloaded the Panis Angelicus score in a key that suited me and taught myself to sing it. It became a piece of music I associate with that first Covid wave.

After the school holidays, the kids did not go back. Home schooling began. I was very glad that I was retired. We lived inside our little family bubble, relieving Michael and Katherine of their three year old twice a week. There was a weekly very early morning trip to the shops, first by Chris and then, when Woolworths introduced “old folk’s hour” at 7am, by me. Other than this we stayed home. My three quarters of a tank of petrol lasted until well into May.

Another new word in our vocabulary was Zoom. There were hilarious stories as the world got used to interactions with other people inside little square boxes…. like the man in a “ties and suits” business meeting, who stood up during the meeting, naked from the waist down, and deaf to the cries from his co workers.

During March I joined a couple of international virtual choirs, rehearsing via Zoom, and viewed later on YouTube. I recorded my contributions and sent them in for the engineers to do their magic. It was a way for choristers all over the world to recover something of what they had lost. I set my alarm for 3am to be part of the Self Isolation Choir’s Messiah “concert”. I chatted with fellow choristers on Facebook. But by May, I was losing interest.

My own choir, Singularity, “met” weekly from late April for the whole year. It meant listening only to the piano playing and singing your part by yourself, muted.

It was a poor imitation of the joy of voices harmonising together, but it was an important way to keep connected. We even held a little “soiree” concert, performing in turn for each other. I sang Panis Angelicus, my Covid anthem, with a YouTube karaoke backing track.

Even as “the numbers” subsided during May, and restrictions eased, singing together in the same room was unthinkable. We had all seen the Science of droplets and aerosols explained. Singing was going to be the last thing to come back. We would have to hang on and wait for a vaccine.

THE FIRST WAVE - SUE'S STORY

March is a jumble of memories and images ranging from the horror of dozens of ambulances lined up in New York streets, refrigerated shipping containers to store the dead outside overflowing hospitals, and the searing beauty of an Italian opera singer performing from her balcony, the aria floating over deserted streets.

Makeshift morgue outside a New York hospital

Bodies inside the refrigerator trucks.

The situation in many places overseas was dire but the virus was starting to get a hold in Australia. In this rapidly evolving situation, within the space of six days, a National Cabinet was formed for the first time since the Second World War, the Prime Minister boldly declared that he would still go to his beloved football match and Victoria declared a State of Emergency and limited gatherings. Four days later, the PM decided not to go to the football and instead closed our international borders to non-residents.

The virus was no longer a distant threat. It became personal. We didn’t feel elderly, but we fitted the category. Anna, Thomas, Riz and Tessa were concerned for us and, although quite challenged by the ‘vulnerable’ label, we did see the wisdom of restricting our contact with family and the outside world. Haircuts were cancelled, Poppy and Bodhi sat outside, when they were dropped at our place before school, and we no longer visited each other’s houses. Anna’s birthday, on the 18th of March, was the first remote birthday celebration of many to come.

End of March, and half a million cases globally, and, as cases grew in Australia, restrictions were imposed and life closed in. We felt very lucky to be an island nation and, as Australians, we felt that we were all in this together. All Australians were dealing with only being allowed to leave home for shopping, exercise, work and care giving. In Victoria, schools broke up a week early, and life changed.

Against this backdrop we tried to learn as much as we could about the virus. We faithfully listened to Norman Swann’s Coronacast, a daily podcast about the Coronavirus, and scoured the Internet for more information. In those early days the advice was that the virus was spread by touch. We carefully avoided touching surfaces, not knowing that aerosol spread was our biggest danger. When shopping, a few people wore masks and even gloves. We worried about eating fruit and vegetables that had been touched by other people, and we wiped down the groceries before putting them away. All cleaning materials, disinfectants, bleach, sanitiser and cakes of soap disappeared from supermarket and hardware shelves. Margaret and I both resorted to a bucket in the car boot containing a bottle of water, soap and a towel. I did the shopping, as Jono’s coronary artery disease put him in an extra vulnerable group.

As suburban supermarkets emptied, country supermarkets reported out of town shoppers, in mini buses, descending and stripping their shelves.

We were able to go to Billy Goat Hill, as it was our second residence, and we took a car full of food in case restrictions tightened and we were unable to get home. We also took our rate notice, in case we were challenged shopping in Alexandra, where we felt very conspicuous. Stories were circulating about people from the city shopping and bringing the virus with them. Apparently, very early one morning, the butcher in Yea was offered thousands of dollars cash for his entire stock of meat. He sent the gentleman away empty handed, telling him in no uncertain terms that he had local customers to supply. The panic buying lasted a few weeks and, once supermarket shelves filled up again, the community anxiety subsided.

Restricted in our activities and unable to see the children, grandchildren, family and friends, we began to spend more time at Billy Goat, where we did not even leave the property for shopping.

Lovely autumn days, and we had plenty to do. Days were dominated by hard work, and evenings by the latest Coronacast and the Covid news from Australia and around the world.

Easter, and having our evening drink, we listened to Andrea Bocelli sing to his deserted city. We could play it as loud as we our blue tooth speaker would allow. We sat in isolation, watching the You Tube clip on the iPad, as this accomplished tenor sang to his deserted city.

The rest of April was dominated by cool burning the kangaroo grass and cleaning up after thinning.

At home the children were coping with home schooling, and parents were supervising where needed. Thomas was still working so Tessa sat Poppy next to her and Bodhi worked on the kitchen bench.

Tessa at the "office" in her dressing gown.

Riz continued to work from home and Anna did online tutoring with her students, while Aiden, Harper and Aurelia worked at their desks. As school work was often efficiently finished by lunchtime, the rest of the day was spent cooking, talking to friends or having ‘watch parties’. Although home schooling suited our grandchildren, it was challenging for some students, particularly the younger ones. I remember Anna telling me that the achievement for one session was having her small student sit on a chair in front of her screen, and not in her wardrobe. Teachers had new disciplinary issues to deal with, such as persuading a Prep student to put his sister down, get back on his chair and turn the microphone on.

Meanwhile, life continued at Billy Goat. Burning and thinning done and the weather now colder and very wet, we started on the erosion work.

Numbers of daily cases were dropping and some there was some easing of restrictions. We decided however to remain cautious and still continue to restrict our lives and social interactions.

THE LULL

MAY 11 - JUNE 9

KEY DATES

May 11 - Some easing of restrictions

May 26 - phased return to classrooms begins

June 1 - Stage 3 restrictions eased

June 9 - last day of zero cases, numbers going up again

The month of May was a catch up time. We hoped it was a gradual return to normality. For most of May, kids were still doing home schooling, most people were working from home, shops and restaurants were still mostly shut, but there was a sniff of life opening up again.

Sue and Jono, after much deliberation, accepted an invitation to lunch at a friends’s house. Only one of the people present had been “out in the world”, so they decided to accept the risk. No “social distancing” happened of course. They sat around a table talking and laughing for several hours. There were no bad consequences, but it only happened once.

Hairdressers reopened during May, though appointment times were limited. Sue’s hairdresser had stories of cutting customers’ hair in the carpark.

I didn’t have my haircut during this time, but I did go the dentist to have a filling replaced; visited the doctor in Kallista, for drive through flu injections and had my car shock absorbers fixed at the Toyota service centre. Each of these felt like venturing out into the dangerous world. We preplanned, and chose our time carefully.

We had planned to ring Toyota late in the day, and say we couldn’t pick the car up, so that it would sit untouched in the yard overnight, and there would be “less virus” on all its surfaces when we collected it the following day. In the end, I picked it up and consciously only touched what I had to, and we didn’t drive it again for a few days.

Guests, where Sue and Jono had their car serviced, went one better. They wiped down every surface in the cars before their customers collected them.

The World Health Organisation, and our own authorities were still refusing to recognise that this corona virus spread primarily through the air, even though the evidence was mounting.

The other big appointment I had put off was my second breast operation. May seemed like the perfect time. Hospitals were available again, and I knew that I had to have it within a certain number of months. The surgeon agreed that this was “permissible surgery”, and we set the date for May 27th. The staff of Ringwood Private hospital did not wear any special protective equipment. Within that little haven, there might as well have been no pandemic.

A few days after, I had occasion to go to our local Ferntree Gully public hospital, and the contrast was noticeable. Everyone was masked. When asked about the difference, the doctor explained that public hospitals took everyone. They couldn’t screen their patients. So they needed to expect many more infection sources. I was careful to see nobody during the next two weeks.

Towards the end of May, there was even more gentle opening up. Schools returned to face to face teaching, gradually, class by class. Aurelia and Harper began footy training again. Alas, that little taste of normal life lasted only one week! As Autumn ticked over into winter, we watched with trepidation, as what would become Melbourne’s second wave appeared on the horizon.

As we begin work on this new post, the first one since February, babies conceived during this plague year are being born. Their normal is a Covid normal. Masked faces, elbow bumps and social distancing have replaced hugs and smiles. They will not be expected to “soldier on” through their cold symptoms. Every one of their days has its “epidemiology”, spelled out in graphs and statistics.

Norman Swan, Medical Science journalist, elevated by the pandemic to superstar status, calls this period, as the world begins the slow process of mass immunisation, “the end of the beginning”. We watch with well worn trepidation. And as we do, it feels like an important time to remember the details, to look back at the milestones, to explore the changes.

THE BEGINNING

JANUARY 25 - MARCH 12

January 25 - First Australian case, Wuhan returnee

January 31 - Chinese returnees have to quarantine in a third country

February 11 - WHO names the novel coronavirus and its disease

February 27 - Travellers from China, Iran and Italy banned

March 2 - First Australian community transmission

March 8 - First Australian death

March 9 - Carey Grammar school closed - staff case

March 12 -WHO calls it a pandemic for the first time, Prime Minister announces first economic stimulus package. Australia has had 142 cases so far.

MARGARET'S STORY

January 2020 had begun for me in hospital, five days after my mastectomy. The East coast of Australia was on fire, and Thurra River camp was already gone by then. But for a cautious decision to cancel their booking, the family would have been evacuated from there, just before it burnt.

Just as my cool hospital room, with its expansive views, insulated me from the smoky, hot air outside, so my personal health crisis kept me from the full force of the terrible losses in Gippsland and New South Wales.

Smoke stretching to New Zealand

I planned to recover over January and be back into my busy life from the beginning of February. I would need a second operation, and had already begun to speculate on the least disruptive way to fit that into the months ahead.

News of a new virus from China was overshadowed by the antics of Trump and the horror of the fires. We heard from our friend Paul, the Point Hicks lighthouse keeper. He sent pictures from an unfamiliar burnt Thurra campground, and stories of sheltering in the lighthouse as the front approached. The first Australian Covid cases on January 25th hardly even caused a ripple in my world.

As February arrived, I felt my grand recovery plan was pretty much on track. I attended the first choir rehearsal, and Sue and I finalised the Recollections post we had begun in December. I was a little more tired than I had anticipated and I put off going back to singing lessons and to yoga. On February 7th I had a haircut. I had no way of knowing that it would be nine months before the next one.

Gradually, as the weeks passed and Autumn soothed the harshness of the Summer, my energy returned, and I began building back more fully. The first worrying Covid signs appeared: on March 2, there was the first Community transmission, and the first Victorian death on March 8. Nevertheless, I began Yoga classes, becoming more used to the lopsided feeling of a prosthetic left breast. The choir’s preparation for our Mikado season hotted up, and I spent lots of time matching costumes to singers, and practising my own part. Now those costumes are folded in boxes under my bed, as we tentatively plan a re-run in 2021.

The last regular engagement in my busy calendar was my weekly singing lesson. I made the arrangement to begin again on Tuesday March 10th, the day after the long weekend. On the Thursday we were all set to go to Bodhi’s twelfth birthday party.

That Tuesday, the WHO finally called it a pandemic and Dan Andrews, with Victorian cases at 36, set the first restrictions. Bodhi’s party was off, Singing lessons and Tuesday’s with Sue ended, and 2020 stretched ahead as a very different year.

THE BEGINNING - SUE'S STORY

By the time Margaret and I returned to our Tuesday routine in 2020 we had lived through a summer dominated by fire, grief, surgery and escalating concern about a virus in China.

In the weeks before Christmas, fires had ravaged much of NSW. Jono’s cousin Robert lost his house in the Blue Mountains and Sydney was covered in a pall of smoke, as mega blazes with towering flames devoured hectare after hectare of bush, destroying thousands and thousands of animals and hundreds of homes. We looked in horror at images of people huddled on beaches, as flames destroyed their town and firefighters were rendered powerless. Against this backdrop, in the week before Christmas, we were packing to go to Thurra. We began to have doubts: it was too dangerous. The bush was tinder dry after two years of drought in East Gippsland and the weather forecast was for hot, windy weather. After much deliberation and a family meeting at Thomas’, we collectively made the decision not to go! The kids were very disappointed, but to their credit, rallied, and began to plan what they could do instead. A week later, on January 31st, the Mallacoota fire roared through Croajingalong National Park, burning much of the park. Familiar places changed forever. Wingan Inlet, the Mueller Valley, the Thurra bridge and campground all gone.

Thurra River Campground after the fire

January, and the fires were still raging as a creeping concern about the spread of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan appeared in news commentary; (COVID-19) the disease, caused by "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2". These words were to become very familiar. On the January the 25th, we had a confirmed case of coronavirus in Melbourne, a returned Chinese citizen from Wuhan. This was the first case in Australia.

Three days later Anna was flying back from India via Singapore. We were very concerned that travellers from China would also be transiting through that transport hub. This is the first time I recall being concerned that the virus could infect a family member, or even someone I knew.

February, and Anna was back safely , the kids returned to school and the fire season continued, as the weather was hot and dry. Overseas, the news was alarming: news reports about escalating cases in China, Italy, Iran and on cruise ships. We began to learn more about how the virus spreads and how contagious it was. We closed our border to some foreign nationals, docking by cruise ships was restricted, and our neighbours cancelled their trip to India.

March, and Bodhi’s birthday on the 12th was cancelled! The consensus was: too many people and too risky in a small space. Jono and I went, vowing to socially distance. Unfamiliar with a behaviour that was to become second nature , we did not socially distance. That night, after discussion, we all decided that from now on birthday celebrations would need to at a safe distance and not inside. Little did we know that in 2020, Sara’s birthday in November, would be the only in-person celebration.

THE FIRST WAVE

MARCH 13 - MAY 11

KEY DATES

March 13 - 36 cases. National Cabinet formed.

March 15 - State of Emergency declared.First restrictions

March 19 - Ruby Princess disperses 2700 passengers around Australia

March 20 - Australia closes borders to non residents

March 22 - School holidays begin a week early. Run on toilet paper

March 30 - All Australian restrictions begin. Four reasons to leave home.

April 10 - Easter at home

April 15 - Home schooling begins

April 16 - Supermarkets introduce “old people’s hour”

April 27 - Massive ramp up in testing

May 5 - outbreak in Cedar Meats Abattoir and meat processing plant.

May 11- Some easing of restrictions

MARGARET'S STORY

During those few days, in that second week of March, there were many signs that things were hotting up, as case numbers reached thirty-six. We had scheduled a choir committee meeting before the next Monday night’s rehearsal, and emails shot round the committee.

By the time the Monday came around, Victoria was in its first day of “State of Emergency”. Only half our singers came. We insisted that everyone wash their hands, and we announced that we had decided to stop rehearsals until after Easter, but we went ahead and sang lustily. We knew nothing of aerosol spread. We had not yet heard about the Seattle choir, who, on March 10th also all washed their hands and sat a little further away from each other. Fifty-two of them were infected and two died.

It took another week before it really began to feel personal. We tut-tutted about the Ruby Princess debacle, though its real impact was yet to become clear. The Australian borders closed to tourists. But these things were just items on the News. The habit of listening to Dan Andrews live in Press Conferences began during this time. I remember sitting in the sun in the late morning, as he announced that school holidays were beginning a week early. My friend Laraine complained on Facebook that she had see people buying huge quantities of toilet rolls. We made jokes about it.

As the numbers of infected people in Australia climbed, the first frissons of alarm began. National Cabinet decided that all of Australia would restrict movement. This was the first time we heard the phrase “four reasons to leave home”, and “essential workers”.

We must have had some knowledge by then of infection rates. I remember waiting until fourteen days after Sage, our grandson, had had his last kinder session before we saw him. We poured over the legal document to see if we were allowed to call our visits “care”. I knitted him a “Bluey jumper”, listening to podcasts, filling in time.

Life became quieter. There were noticeably fewer cars on the roads. Easter came and went. It was the first Easter Sunday for a long time that we had not had lunch with Chris’s parents. We watched Andrea Bocelli sing Panis Angelicus and stroll out to gaze up the empty Milan streets.

Here is the Facebook Post I did on April13th:

As I listened this morning to Andrea Bocelli’s beautiful Easter offering in the empty Duomo in Milan, and watched the footage of empty streets in the world’s great cities, I felt a sense of loss and sadness that I had seen in others, but hadn’t yet felt myself.

The footage reminded me of “The last Time I Saw Paris”, a sad song written by Jerome Kern in 1940. It would be another five years before Paris was liberated.

The camera in Milan roamed over a packed city. All those lives on hold, cooped up little apartments!

In New York, the only sound in the streets is sirens.

But then there is this.....

People in the Punjab, blinking like creatures exiting a cave, look to the north and there, hundreds of kilometres away are the white Himalayas. They have been hidden by pollution for decades.

Factory and vehicle emissions have dropped in China so much that two months worth of pollution reduction “likely has saved the lives of 4,000 kids under 5 and 73,000 adults over 70.”

According to The Climate Group, working from home has the potential to reduce over 300 MILLION tonnes of carbon emissions per year, and surely we will see a lot of that even after the lockdown. And there are stories of animals reclaiming the empty streets all over the world.

I downloaded the Panis Angelicus score in a key that suited me and taught myself to sing it. It became a piece of music I associate with that first Covid wave.

After the school holidays, the kids did not go back. Home schooling began. I was very glad that I was retired. We lived inside our little family bubble, relieving Michael and Katherine of their three year old twice a week. There was a weekly very early morning trip to the shops, first by Chris and then, when Woolworths introduced “old folk’s hour” at 7am, by me. Other than this we stayed home. My three quarters of a tank of petrol lasted until well into May.

Another new word in our vocabulary was Zoom. There were hilarious stories as the world got used to interactions with other people inside little square boxes…. like the man in a “ties and suits” business meeting, who stood up during the meeting, naked from the waist down, and deaf to the cries from his co workers.

During March I joined a couple of international virtual choirs, rehearsing via Zoom, and viewed later on YouTube. I recorded my contributions and sent them in for the engineers to do their magic. It was a way for choristers all over the world to recover something of what they had lost. I set my alarm for 3am to be part of the Self Isolation Choir’s Messiah “concert”. I chatted with fellow choristers on Facebook. But by May, I was losing interest.

My own choir, Singularity, “met” weekly from late April for the whole year. It meant listening only to the piano playing and singing your part by yourself, muted.

It was a poor imitation of the joy of voices harmonising together, but it was an important way to keep connected. We even held a little “soiree” concert, performing in turn for each other. I sang Panis Angelicus, my Covid anthem, with a YouTube karaoke backing track.

Even as “the numbers” subsided during May, and restrictions eased, singing together in the same room was unthinkable. We had all seen the Science of droplets and aerosols explained. Singing was going to be the last thing to come back. We would have to hang on and wait for a vaccine.

THE FIRST WAVE - SUE'S STORY

March is a jumble of memories and images ranging from the horror of dozens of ambulances lined up in New York streets, refrigerated shipping containers to store the dead outside overflowing hospitals, and the searing beauty of an Italian opera singer performing from her balcony, the aria floating over deserted streets.

Makeshift morgue outside a New York hospital

Bodies inside the refrigerator trucks.

The situation in many places overseas was dire but the virus was starting to get a hold in Australia. In this rapidly evolving situation, within the space of six days, a National Cabinet was formed for the first time since the Second World War, the Prime Minister boldly declared that he would still go to his beloved football match and Victoria declared a State of Emergency and limited gatherings. Four days later, the PM decided not to go to the football and instead closed our international borders to non-residents.

The virus was no longer a distant threat. It became personal. We didn’t feel elderly, but we fitted the category. Anna, Thomas, Riz and Tessa were concerned for us and, although quite challenged by the ‘vulnerable’ label, we did see the wisdom of restricting our contact with family and the outside world. Haircuts were cancelled, Poppy and Bodhi sat outside, when they were dropped at our place before school, and we no longer visited each other’s houses. Anna’s birthday, on the 18th of March, was the first remote birthday celebration of many to come.

End of March, and half a million cases globally, and, as cases grew in Australia, restrictions were imposed and life closed in. We felt very lucky to be an island nation and, as Australians, we felt that we were all in this together. All Australians were dealing with only being allowed to leave home for shopping, exercise, work and care giving. In Victoria, schools broke up a week early, and life changed.

Against this backdrop we tried to learn as much as we could about the virus. We faithfully listened to Norman Swann’s Coronacast, a daily podcast about the Coronavirus, and scoured the Internet for more information. In those early days the advice was that the virus was spread by touch. We carefully avoided touching surfaces, not knowing that aerosol spread was our biggest danger. When shopping, a few people wore masks and even gloves. We worried about eating fruit and vegetables that had been touched by other people, and we wiped down the groceries before putting them away. All cleaning materials, disinfectants, bleach, sanitiser and cakes of soap disappeared from supermarket and hardware shelves. Margaret and I both resorted to a bucket in the car boot containing a bottle of water, soap and a towel. I did the shopping, as Jono’s coronary artery disease put him in an extra vulnerable group.

As suburban supermarkets emptied, country supermarkets reported out of town shoppers, in mini buses, descending and stripping their shelves.

We were able to go to Billy Goat Hill, as it was our second residence, and we took a car full of food in case restrictions tightened and we were unable to get home. We also took our rate notice, in case we were challenged shopping in Alexandra, where we felt very conspicuous. Stories were circulating about people from the city shopping and bringing the virus with them. Apparently, very early one morning, the butcher in Yea was offered thousands of dollars cash for his entire stock of meat. He sent the gentleman away empty handed, telling him in no uncertain terms that he had local customers to supply. The panic buying lasted a few weeks and, once supermarket shelves filled up again, the community anxiety subsided.