Fire and Storm

MY COUNTRY By Dorothy MacKellar

‘I love a sunburnt country,

A land of sweeping plains,

Of ragged mountain ranges,

Of droughts and flooding rains.

I love her far horizons,

I love her jewel sea.

Her beauty and her terror,

The wide brown land for me.

Margaret and I learnt this iconic poem during our respective Grade 6 years and many of its lines are still etched in memory. In fact we can still recite much of it with exactly the same intonation and expression. This poem, written in 1904, captures the tenor of our post, Fire and Storm.

Fire, still very much part of our lives, has also been part of our family history.

BLACK THURSDAY 1851

The first reference to fire was in1851 with the fire known as ‘Black Thursday’.

Painting by William Strutt

This was the first catastrophic bushfire faced by white settlers in Victoria. The lead up to the fire followed what is now a familiar pattern of events. Reports at the time said that there had been wet years of lush growth followed by severe drought, leaving the bush and long grass tinder dry. Thursday the 6th of February dawned hot and windy, and the fires took off, leaving one quarter of the state black and smouldering. Our antecedents, the Bourke’s of Pakenham, were caught up in the fires in a dramatic way. Shortly before Black Thursday the Bourke’s had taken possession of Bourke’s Hotel in Pakenham. Michael Bourke remained at their selection, while Mrs Bourke was to run the hotel and Post Office.

‘On Black Thursday the whole district was ablaze. Mr Bourke was trying hard to save the station property. Water having been exhausted, milk was brought into play and ultimately the run was saved. Word was brought to him that the hotel property at Pakenham was surrounded by fire. Galloping down there, he found his wife and her children had saved themselves by crouching in the water in the bed of the creek.’

We took this photo of the exact spot, during our visit to Pakenham.

BACCHUS MARSH FIRE 1928

From an article in ‘The Argus' Thurs 12th July 1928

"FIRE AT BACCHUS MARSH.THREE SHOPS DESTROYED"

This was a report on the fire suffered by our grand parents, Alf and Alfreda, in which they lost almost everything, but escaped with their lives. We heard dramatic stories of this fire in childhood and is told below by Marge and Alice on the tape they made in 1990.

The hardware shop was their business, and they had gone out on their own, in an already a difficult time of their lives. Aunty Bert was staying with them to help out, as was her role in the family, as the unmarried sister. Auntie Bert, Alf and Alfreda would have been in their early thirties,Alice was five and Marge three years older. Thank goodness Bert was there as she seems to have had a cool head and took action to get everyone out as the fire took hold.

Marge and Alice’s recollection is fairly accurate, as the newspaper report comments on the strong North wind and the poor water pressure that hampered the fire fighting.

The Argus reports that at one stage,

…. the premises of Mr. G. H. Anderson were threatened , but this danger passed, with a change in the direction of the wind, A good portion of the stocks of Messrs. McLaren and Coates was saved, but considerable damage was done to Mr. Phillip’s stock. It is understood that all buildings and stock, except that of Mr. McLaren, were insured.

At half-past 7 o'clock, in the morning the fire was under control, and all that was left of three of the shops were the walls.’

Mr McLaren may have been uninsured but Alf was definitely not, as he had been unable to pay the insurance. They lost nearly everything.

We had wondered about Alice’s comment about Auntie Bert’s friend Nell Pearce, whose family took them all in after the fire, and yes it was a large and impressive brick house, still standing today:

As Alice states the Pearces were an influential family in the town. They had been an early pioneering family in the area. They built and established the General Store that presumably was very profitable, supplying the miners on the way to the Goldfields as well as the local community. The family then went into farming and other small businesses, and were influential in civic affairs.

Auntie Bert maintained a lifelong friendship with Nell, and neither of them married. I remember Nell Pearce being a name mentioned in conversation and I have a vague recollection of her as an imposing figure. I also remember her at Auntie Bert’ s sewing rooms in Camberwell. She was probably there for a fitting. Little did we know the history behind that friendship.

After cleaning up and sorting our their affairs Alf and Alfreda, the girls and presumably Auntie Bert left Bacchus Marsh and stayed with Grandpa and Grandma Holm in Surrey Hills. Alf then got a job in Croydon as manager of the hardware shop, where they spent many happy years.

BLACK FRIDAY 1939

After the 1851 fires, bush fires occurred in many parts of the State with predictable monotony. The next major statewide fire was in 1939, once again after a prolonged drought. High temperatures and strong northerly winds fanned separate fires that eventually combined and created a massive fire front that swept mainly over the mountain country in the northeast of Victoria, and along the coast in the southwest.

Lilydale Brigade 1939.

Source - CFA Website

More than two million hectares were burnt in the 1939 fires.They lasted for a week. Many, unable to be controlled, were left to burn out.

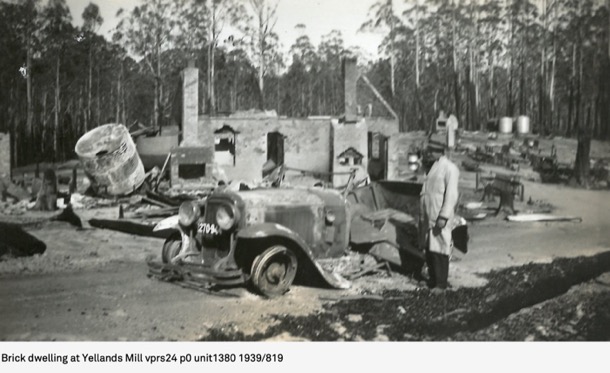

Yellands Mill, where 15 men died:

The extensive damage to over two million hectares of farmland and forest, not to mention the loss of livestock and lives, prompted a Royal Commission. They were tasked with examining the causes of the fire and making recommendations for future management.

The Royal Commission’s specific recommendation was that the various Bush Brigades, and Country Fire Brigades be amalgamated to form a single organisation to fight fire on private land outside the Metropolitan Area. The Forest Commission was responsible for fire on public land and the Metropolitan Fire Brigade was responsible for fire in the Metropolitan Area. Instead of a myriad of uncoordinated small brigades these three organisations were responsible for fighting fires in Victoria.

EARLY BUSHFIRE EXPERIENCE - MARGARET

My first memory of wildfire is of a fire on the empty block next door. The vegetation was sparse: weeds and gorse, with patches of bare clay.

We think it was around 1955. Sue doesn’t remember it, and was probably at school. But I have a clear memory and so I was probably at least four. The image in my mind is of mum, armed with a hessian bag, beating flames. Hessian is a coarse, rough brown fabric made from jute, widely used for packaging. We had a supply of hessian bags, saved from buying bulk chook food. Mum was not a “bush woman” in the Henry Lawson image, but she would have seen this form of fire fighting, and she apparently felt able to take it on.

Fire fighting with a hessian bag.

I don’t remember bush fires being a big part of my life as a child, until I was eleven, in 1962. That year was a big bushfire year in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs: 32 people died and 450 houses were lost. Areas affected included Mitcham, less than ten kilometres away from our place. We were never in danger in suburban Box Hill South, but there would have been a red glow in the sky, and the vivid memory I have of burning gum leaves falling in the back yard, is probably from this fire.

In 1979, I moved to the Dandenong Ranges, where the CFA had much more of a presence, and bushfire awareness was part of everyday life over Summer.

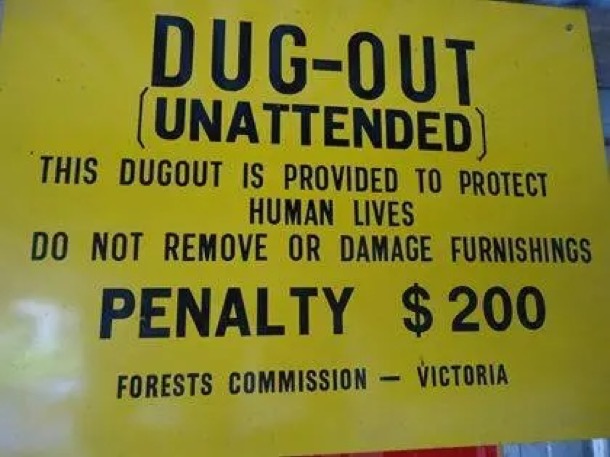

In those first few years, there was still on old dugout just over the road in the forest. It had a wooden sign “Dugout” and what looked like a large wombat hole. A closer look revealed a heavy grey army blanket hanging over the entrance. During a fire, this would be kept wet. Inside was a rounded cave, with earthen floor, ceiling and walls. It would have held a maximum of six adults. There was a metal bucket and a pile of musty grey wooden blankets. I guess it might keep you safe while a canopy fire raced overhead, but I wouldn’t want to rely on it.

The CFA were, and still are, omnipresent. On weekends they collect donations at major intersections. On Good Friday, and in the week before Christmas, they drive through the streets, playing piped music and rattling collection tins. Their sirens regularly echo through the Hills. We can hear the Belgrave, Upwey and Kallista sirens from our place, and sometimes all three will go off. In the past, the siren was used to call in the volunteers, and on a set night of the week, on CFA practice night, they would test the siren at a set time. We like that the sirens are still used, not so much as a specific warning, but as part of our aural landscape.

Nowadays, when we hear a siren, we go straight to the Victorian Emergency app, to check what has happened. Often it’s a house fire, a car accident, a small bush fire. During the Summer months we are more attuned to the sound. Our practice has long been to evacuate on days of dangerous fire weather.

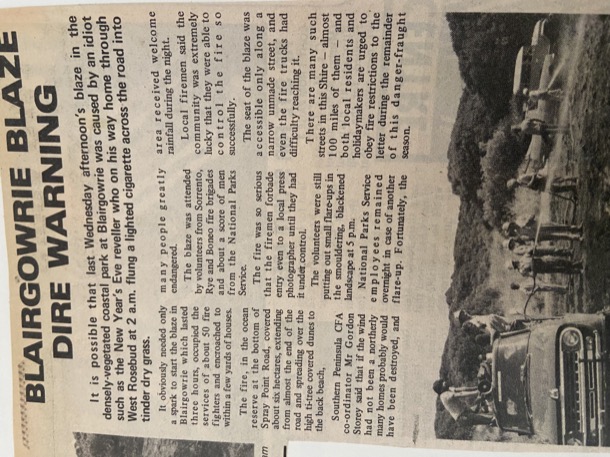

BLAIRGOWRIE FIRE 1980 - SUE

My only experience of fire first hand, was in 1980 at Janey’s house at Blairgowrie. We had all just sat down to lunch. Anna was nearly three and I was pregnant with Thomas. Everything was tinder dry, as it was January and we were in the middle of the 1979-1983 Eastern Australian Drought.

Halfway through lunch there were loud knocks at the door, and a panicking young man asked us for a hose, as he has seen a small fire beginning to build on the Spray Point Road, just fifty metres from the house. Jono and Janey raced down to investigate, but realised that they had not a chance of stopping the fire. It was spreading quickly, fanned by a strong north wind. This was a stroke of luck as this meant it was spreading away from us and towards the beach. We called the CFA who responded promptly, parking several fire trucks at the hydrant on the nature strip.

We were told to block the downpipes with oranges, fill the gutters with water, and shelter inside. The fire was brought under control fairly quickly but not before six hectares of the National Park was burnt.

It would have been a different story if the wind had changed and pushed the fire towards Janey’s house and of course all the other houses.

Local newspapers at the time reported on the fire and issued warnings and advice to residents and holiday makers for the rest of the holiday season that was only just beginning.

ASH WEDNESDAY

SUE

On Ash Wednesday I was at home with Thomas, as Anna had just started school. Thomas was happily playing with water in the shade of our pergola, as it was a very hot day. A nasty north wind intensified as the day wore on and many fires started across Victoria. I was listening to the ABC afternoon show hosted by Tony Delroy, who, as fires broke out, was reporting the outbreaks in real time. He also took many calls from people desperate for information. There were no centralised communications hub, warning system, or, of course, mobile phones. As the fires continued to burn during the evening and that night, the radio was the only source of state wide information. The 3LO radio hosts worked on a roster system to get the information out.

Since its inception the ABC had been responsible for emergency broadcasting, but only on the news bulletins.. In 1997 Ian Mannix was appointed as Program Director for Local Radio Victoria. He changed the nature of emergency broadcasting during the 1997 bush fire in the Dandenong Ranges. The fires burnt for days, three people died and forty homes were destroyed. Mannix asked the CFA for advice on what to say to to listeners ‘who were confronted with flames.’…Interestingly, the CFA had no experience of giving warnings and had never written a warning for people at risk.

Mannix went ahead and took the lead in creating the ABC’s approach to emergency broadcasting. He developed guidelines that included warnings at set intervals, including bush fire alerts for low level fires and urgent threat warnings for more serious fires. The system used in Victoria was expanded nationally after Black Saturday in 2009. Further recommendations were made by the Black Saturday Royal Commission that future refined and expanded the warning systems to television and commercial radio.

From this pioneering work by Ian Mannix, we now have an Australia wide warning system, and broadcasting training and guidelines in each state.

Ian Mannix oversaw the development and implementation of these systems and deservedly received the Australian Public Service Medal in 2012.

MARGARET

The first actual fire we had to deal with in Belgrave was the 1983 Ash Wednesday.

The name “Ash Wednesday” is nothing to do with ash from bushfires. It’s a historical/religious reference. It happens every year, and it marks the beginning of Lent, leading up to Easter, in lots of Christian denominations. It follows Shrove Tuesday, Mardi Gras … the last day of feasting before the deprivations of Lent. The ‘ash’ is sprinkled onto heads or swiped across foreheads as part of the Ash Wednesday service.

1982 had had a very droughty Winter, Spring and Summer. The little creek that runs through the forest over the road had almost stopped, and underfoot the leaves crackled.

The 1983 Melbourne dust storm, when 50,000 tonnes of Mallee topsoil turned the sky dark brown across the city, happened in early February. For me, it hit as I was crossing Burwood Highway on my way to the Ferntree Gully hotel, for an after school cool drink. The dust cloud was over 300 metres high and 500 kilometres long, and darkened the sky for an hour. It’s one of those iconic events where everyone can tell you where they were when it hit.

Image credit: Katsuhiro Abe/BOM

There were many fires that Summer. The CFA across Victoria attended nearly 3,200 fires. Wednesday February 16th was particularly hot and windy.

That morning I had woken feeling nauseous and weak. I rang in sick, and went back to bed. Within a few weeks, I would find out that this had been the beginning of morning sickness. Michael was born that October.

Later in the day I had a phone call from a friend who lived locally, suggesting I might consider leaving, as he had heard there was a fire in Belgrave Heights. Outside was stifling. My neighbour was packing her car but she was expecting to wait and see. I don’t remember having any sense of danger, though, later, we learnt that it was only the late afternoon wind change that stopped the fire from sweeping through Belgrave township and on to our place.

Photo: Tonia Van der Dungen. Christmas Hills CFA

Wind changes during bush fires dramatically widen the fire front, and this one swept through Belgrave South and on to Cockatoo and Upper Beaconsfield.

I don’t remember this, but apparently Ian and Lois were visiting me that day. Lois was pregnant with Sam who was born that winter. Ian speaks of driving home in the afternoon, and taking the sudden decision to drive straight on through Belgrave, rather than the more logical route through to Belgrave South. This would have been exactly the time of day when the fire swept through across the road they would have been on.

Later there were many stories, horrifying and heroic. In Cockatoo, 300 people sheltered during the night in the kindergarten, as a handful of local men kept the flames and embers at bay, saving many lives.

Across Victoria, 75 people died, more than 200,00 hectares were burnt and 2000 homes and buildings were damaged.

Friends from the suburbs rang to check that I was ok. Our little patch of the Dandenongs was untouched, but one didn’t have to drive very far to see the black horror.

Photo: Critchley Parker Junior Reserve. Upper Beaconsfield CFA

Ten years later, I began teaching at Monbulk College, and some of our students were still affected by their experiences in 1983. My friend and colleague Sarah had her Year 8 English class make a booklet marking the ten year anniversary. Everyone had stories, which the students typed up and put together. It remains an important part of the history of Dandenong Ranges, and other affected parts of Victoria.

The tragic Ash Wednesday fires were like those of 1939 Black Friday in intensity, if not in range. They confronted the modern firefighting community with the limits of its capacity and technology. Among the 75 dead, 17 firefighters died that day, some of them next to their well equipped tankers on a forest road in Upper Beaconsfield, when the wind changed and the firestorm swept over them. Changes in firefighting strategies and philosophies were inevitable. The community needed to be better informed and more involved. This is certainly my experience. I was so naive and ignorant, compared to what we expect from Hills people nowadays! There was a huge Royal Commission.

It seemed, as the Commission heard people’s Ash Wednesday stories, that the most dangerous situations people faced were from hurried departures. People died in their cars, not their homes. But the CFA could not guarantee to be there during huge bush fires, protecting every home.

And then there were stories of people actively defending their homes from ember attacks, and saving them. “People save houses. Houses save people.” was the mantra.

The “stay or go” policy began to be developed. As the professionalisation of firefighting, and the ‘Science’ of fire behaviour developed, ordinary people’s anecdotes were often disregarded as over hyped and hysterical.

There was a huge campaign to teach the population about how to prepare their homes, and defend them. Because it was so centralised, the people who lived on the edges of grasslands and those, like us, in what nowadays we call the “flame zone”, were given the same advice. The “go” part of “stay or go” felt like an afterthought for people who were not able bodied. I remember some of our neighbours’ plans were that the men and older boys would “stay” and the women and little children would “go”.

In 1987 the very first General Achievement Test had as one of its tasks information about how to prepare a home for bushfire. It was clearly in the zeitgeist.

My personal experience of this policy is encapsulated by a CFA Fireguard group meeting, in the years leading up to 2010, that we attended on our neighbour’s verandah. The CFA man explained patiently about how bushfires behave, and how we should be preparing our houses, so that we could defend them. The expectation was clearly that we and our neighbours would stay, in the case of a bushfire, and, with mops and buckets of water, we would put out any embers that threatened out house. We pointed to the towering ash forest, metres from our house, and told him we didn’t think our house would be defendable. He was not impressed.

Throughout the Millennial drought, from 1997 to 2009, during the most severe summers, we kept a trailer full of things at Chris’s parents’ place, and had a very clear plan. We evacuated quite a number of times, staying in their spare room. The plan was to insure fully, and simply not to be there during dangerous times. The local schools built fire refuges, and the CFA kept on with its “stay and defend” message. Water saving advice was everywhere. Like many others, we set up a grey water system to water our garden.

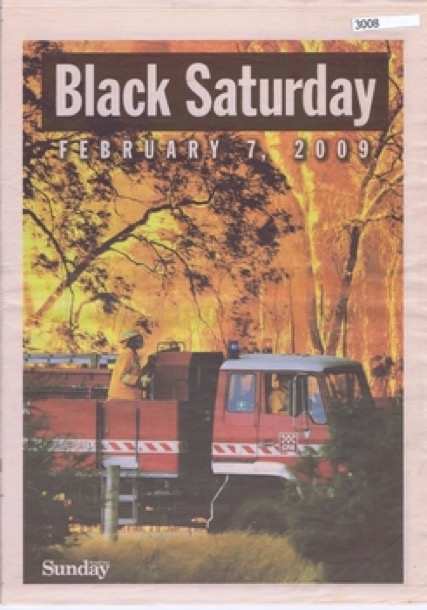

BLACK SATURDAY - MARGARET

And then came the summer of 2008-9. It had been particularly dry and hot. This was the summer when tree fern fronds were scorched, lawns died and record high temperatures were broken day after day. The forecast for the first week of February looked horrendous in advance, with temperatures of 48 degrees forecast, and Chris and I decided to take ourselves camping by the Thurra river, and wait it out. I was glad to be retired by then!

We followed the news of Black Saturday, on the radio, and, once the cool change hit, we packed up and drove out along the Thurra Road, as news of the death toll mounted. Along the Princes Highway, we saw fire fighters’ camp sites with row after row of little tents. The air was smokey, and through the Latrobe Valley we drove through a blackened landscape. At home, the garden was scorched and everything still crackled underfoot.

Back with television coverage, we watched interviews with people who had miraculously survived, saw footage of people’s fire refuges that had been easily breached, and heard the stories of person after person, traumatised by their unsuccessful attempts to defend their homes. 173 people had died, 120 of them in the Kinglake area. More than 450 hectares had burned and 3500 buildings, 200 of them houses, had been destroyed.

Herald-Sun

That cool change was not the end of the 2009 fire season. We evacuated a number of times that February. One day, a fire bug lit a fire just up the hill from us. I was sitting outside, and heard the crackle as flames licked up a nearby gum tree. Chris was walking in the forest. As I drove down to the Belgrave carpark, he was walking quickly back down through the forest, having seen the smoke. When he met a wall of flames, he backtracked hastily, headed toward the road, and hitched a ride with a stranger to near home. The wind was blowing the danger away from our place. I have been mocked mercilessly for my paper post it note on the door telling him I’d gone to the Belgrave car park, but at least he knew that I was out of danger.

In the car park, a gaggle of us watched the Elvis fire bombing helicopters head up the hill, and cheered, and very soon the whole drama was over.

2009 marked the end of the Millennial drought years. Summers since then have been cooler and wetter. But the legacy has been an obsession with rainfall figures, forecasts and climate outlooks.

Our local community facebook page has a member who is a forecaster with the Bureau of Meteorology, who posts every time there is a weather anomaly. It is clear from the responses to him, that we are not alone in our anxiety about rainfall.

THE BIG STORM - MARGARET

It was winter, 2021. There had been yet another Covid lockdown, this one lasting two weeks, finishing on June 10th. Life quickly went back to normal for most people in Melbourne.

But for us in the Dandenongs, the evening of June 9th, and the next morning, brought a massive windstorm which brought down huge swathes of trees, many across roads and onto 112 houses. The wind came at 120kph, but it came from an unusual direction, and our shallow rooted mountain trees were largely untested from that direction. They fell, roots and all, in their hundreds.

Even though the power went off immediately, and all the mobile towers were out, there were 9,500 calls for help logged by the SES. People were trapped in their houses, and many streets, including Michael and Katherine’s were blocked off. There was no way of communicating, in or out, for many days.

My most vivid memory of the storm comes from early on the morning of the tenth. Chris was standing with a view to the north of the forest out the window. His eyes widened, and yet another a great crash came from the forest. He had watched a two hundred foot tall mountain ash eucalypt gracefully fall sideways, taking down another tree of similar size, which in turn took out another one. Like enormous dominos, the three of them had joined the huge pile of previous victims on the forest floor. Later on we stood on the road, looking down where they had fallen and counted thirteen giant trees lying in a messy tangle.

Elsewhere in the Hills, this carnage had been repeated in town after town. We lucky ones who still had homes, watched with dismay as the power company’s estimates of power restoration stretched out beyond a week. Eventually we were able to drive out. It was a weird feeling to drive down onto the flat and find life going on as normal. For us the feeling was very much as if we were still in lockdown. On the Monday evening, I went to choir rehearsal in Ferntree Gully, blinking in the unaccustomed bright lights. Many of us Hills residents had brought items to be recharged during the evening. At end of the night we drove back up into the darkened Hills.

At home, we went into camping mode. There was no hot water, but we had plenty of fire wood, and our very effective wood heater. We cooked with gas and our little portable gas fridge kept our essentials cold. I took to having my bucket bath in the afternoon, when it wasn’t quite so cold in the bathroom. It was ten days before our power came back on, on June 20th.

The reprieve from lockdown lasted only a month. By July 16, Melbourne was back into working from home, home schooling, and leaving home only for essential purposes.

Pins and Needles

SUE

Although I have grown up with sewing and sewers in my life, it has never captured my interest, until recently. I have horrible memories of sewing classes in Year Seven. We were supplied with rectangular brown, cardboard sewing boxes, which held all our supplies and the current sewing task. All went relatively smoothly during the first half of the year as we learnt to use the machines and made our cookery apron and cap for Home Economics classes in Year Eight. Then we graduated to making a white, lawn, lace trimmed slip with french seams.

I must have made several mistakes and had to unpick the french seams around the bust several times and my work became very grubby and worn. I looked with envy at the neat and pristine garments of some of my classmates. Starting again was not an option so I decided to smuggle it out and fix it at home. This was strictly forbidden! In the general busyness in the storeroom as the girls put their sewing boxes on the shelves, I hid the offending item under my blazer. Even at home it was very difficult to resew neatly, because of all the needle holes and general grubbiness. At least I could move on with the easier straight seams and the hem. Thank goodness I was not caught smuggling the sewing back into my sewing box. I finished the garment but never wore it. I am sure I would only have received a D, which I would not have liked.

My next foray into sewing was in the first year of my Art and Craft course. The first year was “dressmaking”. I did not enjoy it much, but it was not horrific, as the petticoat had been. I certainly did not want to teach sewing, and I was never asked to, thank goodness.

Surprisingly, I have recently started sewing again. I, like many others, started sewing in lockdown during the Covid pandemic. I am part of a widespread sewing resurgence, facilitated by the technological advances that give me access to fabrics and patterns all over the world and in Melbourne too.

Choosing the fabric and pattern are the aspects of dressmaking that have changed the most. For instance, I recently bought a winter coat pattern and fabric. Once, I would have gone to a local shop and leafed through thick, well thumbed and worn.pattern books by Butterwick, McCalls and Vogue.

Instead, I chose my vintage coat pattern online, from a business in Germany. It was converted to a PDF format and delivery was almost instantaneous. Then the fun began as the pattern had to be printed. Two options were available for printing. The pattern could be printed on a home printer in A4, with the disadvantage of the pages needing to be joined with sticky tape. The alternative was to go to Officeworks and have the printing done for me, as one large sheet.

I have also discovered the joys of shopping worldwide for fabric. One of my favourites is a haberdasher in Hull in the UK, whose ethos is the creation of long lasting, wearable clothes from their patterns and their sustainably and ethically sourced fabrics. Merchant and Mills is part of a worldwide niche market, that is a reaction to the fast fashion industry, where very cheap, mass produced garments are expected to be thrown away after only a few wears.

‘This European laundered linen, tumbled at the mill for softness, is a dusty peach and dark brown. It is produced in small batches in Eastern Europe where there is a strong heritage of spinning and weaving linen fabric’

MARGARET

One of the joys of retirement is having time for the little ones. For me, this included making special things for them, mostly sewing and knitting, and always geared to their particular interests and preferences.

Sometimes the occasion was birthdays and Christmases, but sometimes special requests came my way.

The first of these was a Christmas: matching pink fairy dresses for the three little girls. Here is Harper in hers:

Later on, Harper’s colour preferences changed. For more than a year, she was all about cyan. You and I might have called this colour aqua or turquoise.

This was the colour specified for her special request for a jumper with a bunny on it for her, and one with a girl on it for her bunny.

Aurelia was exactly the generation to be all about Disney’s Frozen. Her first frozen dress was a bought one, and she wore it out, before she tired of it. Thus it was, that my first Frozen job was to rehabilitate it:

Then, when Frozen 2 came out, with that green dress, Aurelia and I trooped off to Spotlight to choose fabrics for her new one.

Here, she models the front and back of the final product:

When my own grandchild came along, son of an artist, my initial contribution was a lacy baby blanket, not baby blue, but dark grey.

His first winter coat was also designed by Katherine, and made by me:

After a while I began knitting him jumpers to match his preferences.

The first one was Percy, his favourite Thomas the Tank Engine character:

Then Bluey:

Optimus Prime:

And, the most recent, a Minecraft T shirt, with, by request, a Sniffer:

THE ACCIDENTAL CRAFTIVIST.

In 2013, Chris and I became involved with the community protest against the building of a McDonald’s in Tecoma.

Over time, this evolved into groups of protestors spending many hours standing holding signs on the main road, and maintaining a vigil at the back of the building site.

My favoured place was sitting at the back gate, with a camp chair. Of course I took my knitting.

Here is a typical scene from “the site” at that time. The police were frequent visitors. For a long time, there was stalemate. We were backed by the union movement, and no building contractor could be found.

As the building progressed, we were no longer able to meet at the back gate. Every morning my friend Jan put up a little shelter we called “headquarters”. Every truck had to run the gauntlet of polite older women explaining why they should not enter the site.

The Banner.

After a while, as we all finished off our various projects, we began knitting squares with all our scrap wool.

We became a group of close friends, and called ourselves The Picket Knitters.

As our movement became more and more well known, we had people from all over the place sending squares. We embroidered the place of origin on some of them. This one came from Cairns.

Eventually we put all the squares together, and made it into a banner.

By the time we had the official launch of the banner, the building was under way. Here, the knitters crouch behind the road barrier, with crossed needles. Sue and I are both there.

The local papers loved us.

Eventually, we presented the banner to our fellow craftivists, the Knitting Nanas of Toolangi. We reconfigured the squares and it became part of their Great Tree Project.

Here it is decorating the base of one of the precious Mountain Ash trees.

Gnomageddon

“Gnome Maccas”, derived from our “No Maccas in Tecoma” slogan, spawned a range of Gnome related activities. The biggest of these was our Gnomageddon, where the community gathered to break the Guinness Book of Records record of the most people dressed as gnomes.

I made all our knitters a red gnome hat.

Here are a few Picket Knitters in their gnome outfits.

And even a gnome rat.

Once the McDonald’s in Tecoma opened, albeit usually deserted and initially the lowest grossing McDonald’s in the country, we continued to meet at each others houses.

In 2016, we all created tea cosies and entered them in the Fish Creek Tea Cosy Festival.

Here is my offering:

The local paper chased us up to find out what The Picket Knitters were doing now.

This article prompted a phone call from a Melbourne Radio Station shock jock. Based on the tone of the article, he was very excited by the idea he could paint us as serial protesters for hire. I very much enjoyed my live interview with him, where his aim was completely transparent. When he pressed me for possible “causes” we might move on to, clearly hoping for left wing politics he could ridicule, I listed a range of completely apolitical charities, and played my role of “just an ordinary person” who “of course didn’t want a McDonald’s so near the forest”.

We no longer knit together, but we do meet every fortnight for a lavish lunch and a long chat about how to put the world to rights.

ALICE

This is Sue and Margaret in about 1955.

Two small girls, sisters, on a cold winter day in suburban Box Hill in the nineteen fifties.

What does it tell us of life then and the different world we lived in?

From the bottom up, starting with our shoes: We both are wearing lace up shoes, Margaret’s may have been hand me downs. She had a lot of these, as clothes were an expensive item to buy. Mine were my school shoes and these shoes were our one pair: worn to school or kinder, to play, to visit and to church on Sunday. On wet days we wore galoshes over them. These were rubberised over shoes, that fitted over the shoes, saving both feet and shoes from a soaking.

The life of our expensive shoes were prolonged by being reheeled by our father using his shoe last.

He also put little u shaped metal clips on the outer edge of the heel and toes to prevent wear on those vulnerable areas. Amazingly, looking for photos of ‘vintage ‘heel and toe clips I came across a host of You Tube videos of how to fix them to your shoes It is still a thing on leather soled shoes. The two worlds meet.

Our cotton socks were much the same as today. We only had a few pairs. Above these ankle socks were bare legs, in the depth of winter. We both remember cold legs on winter mornings: little girl plump legs with that blueish pink tinge.

At least we had woollen skirts that kept us warm. Once again only one, and home made by our mother. They were always tartan, pleated and then sewn to a cotton calico bodice.

The cotton bodice was at times a little grubby, but was usually hidden under our hand knitted woollen jumper or cardigan. Under this was a singlet possibly woollen. Margaret remembers shocking our mother. School Open Day was quite a big deal with many, mainly mothers in attendance. Mum walked into class confronted by an oblivious Margaret without her jumper on, as it was hot. She was sporting her tartan skirt, complete with a grubby bodice held up at the shoulder with a large safety pin. What a sight!

We think we wore these garments for almost everything we did during winter, from roller skating to going to school. We vaguely remember having twin sets to wear for best with the pleated skirt and a winter coat and raincoat, all worn with.our school, lace up shoes.

And then there was summer sewing.

It’s the week before Christmas. School has broken up, and four children, a dog and a cat clutter up the house. It’s hot, and there is no air conditioning. Not even a fan.

Christmas presents are partly organised but still require a few trips to Chadstone Shopping Centre.

In the garage, Dad is tuning the car, ready for its two hour trip to Shoreham camp. The tent and most of the camp furniture has already been set up, but a trailer full of odds and ends is still to be packed.

The plan is to leave early on Boxing Day.

In the centre of the house, between the kitchen and dining room, is a scene of colourful mayhem.

The sewing machine runs all day and into the night.

Cotton fabrics have been bought, perhaps at a discount fabric shop. They are spread out across the floor, with well used pattern pieces pinned to them. Mum crawls across the fabric cutting out multiple pieces. She makes enough shorts and tops for us each to have a set to wear and a set in the wash. There are hand-me-downs involved for me, the second child.

We find it hard to remember the details of her sewing. How were the seams finished? Were the necklines bound or faced? The hems were all hand sewn: we can both remember hems coming undone.

She didn’t cut the thread ends as she went, there were always multiple loose threads to trim off at the end.

In this photo, taken about 1958, little Sue and Margaret stand in the centre, in that year’s shorts and striped tops.

AUNTIE BERT

Our Great Auntie Bert was an important person in our lives and those of our extended family. We have fond memories of her kindness, but it was only as we researched the position of sewing in our family history, that we fully appreciated her dressmaking legacy. We knew that she had had a career as a dressmaker, and had run her own business. She passed on her dressmaking and fitting skills to Margaret and me, and to our mother and Auntie Marge, but we had not appreciated the thoughtfulness and kindness that was an intrinsic part of each garment.

My crushed strawberry viyella dress and Margaret’s mustard yellow check one epitomise this:

Now that I am sewing more, I can begin to appreciate the level of skill and detailing involved in the creation of these winter dresses. Margaret’s dress is made in a mustard check with a plain contrast panel and collar insert, all beautifully sewn and constructed. My dress, in one colour has detailed pleating on the bodice and skirt and a scalloped edge stitched waist that would have been fiendishly difficult to sew. Hopefully Auntie Bert would have enjoyed creating these “best” dresses, in which her love and care for her family are so evident.

Auntie Bert was also called upon to make many “best” dresses for the adult women of the family, some of them wedding outfits.

In my late teens when Auntie Bert was living in the flat behind our house, she made me a beautiful tweed winter overcoat , fully lined. I wish I still had it. During the process she taught me some of her tailoring techniques, for instance how to attach hair canvas to the collar , stitching it to ensure an even roll over.

During the last years of her life Auntie Bert lived with her sister’s family at the Cockatoo farm, as we explained in our post ‘Auntie Bert: A Sterling Character.’. During this time she was mostly clad in clothes she had made. In winter, she wore straight woollen skirts and layers of woollen jumpers and cardigans. In summer she wore a dress and cardigan, more often than not, covered by an apron. We never saw her in a beanie, which her sister wore constantly, even inside.

Sewing in many guises has been a feature of the lives of women in our family for generations. Probably there are more stories even further back that we are unaware of. In this short story we have gone from treadle machines, paper patterns and sewing for necessity, to sewing for pleasure and sewing as a form of protest.

Hair

This post therefore is about hairstyles, but we have allowed ourselves a much broader scope.

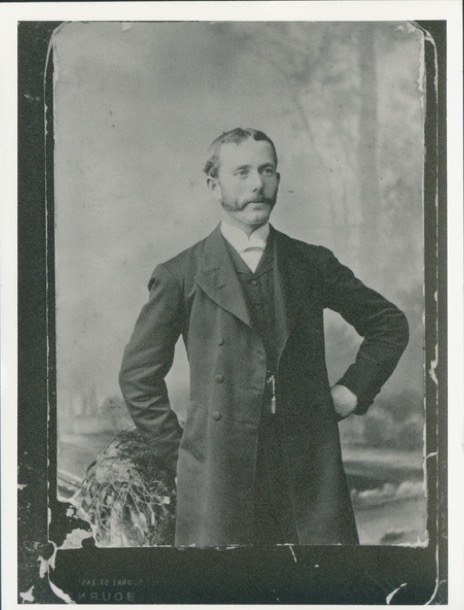

ALFRED JOHN COATES

Alfred John Coates, born in 1857, was probably in his late twenties when this photo was taken. He was our maternal great grandfather and was a Methodist Pastor for most of his working life. In this photograph Alfred is a young man in prime of life, dressed in formal dress and sporting the fashion of the day: mutton chop whiskers, carefully manicured to join artfully with the moustache. A man of destiny, the misty ‘bush’ behind him, he stands erect, eyes on the future. At this time Alfred was apparently a boiler maker in Ballarat.

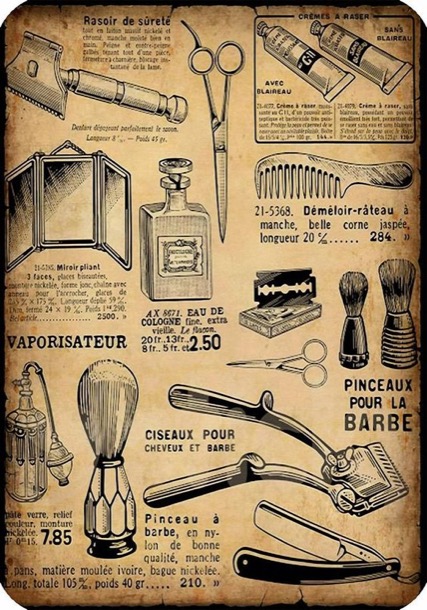

Men’s facial hair trends were changing rapidly in the late 1800s. Long beards were out and clean chins and cheeks and a well-manicured moustache were in. To achieve this look men would need to go to a barber two to three times a week or shave themselves.

Shaving oneself may have been a financial necessity at times but it could also be a dangerous procedure. Shaving was done with a straight steel razor that required care and expertise, not only in the act of shaving the gentleman, but also in the care of the blade. To keep it sharp, the blade was rubbed against a leather or canvas strap before each new shave. As well as the blade, shaving soap, shaving brushes, combs, oils and wax were essential items to achieve the desired effect.

Having a photograph taken in a studio was a special occasion and a relatively expensive exercise. One can imagine that Alfred may have had a trip to the barber to ensure that he looked his best.

Safety steel razor blades that made shaving much easier were not invented until 1895 by an American business man with French heritage.

King C. Gillette invented a low cost blade that was easily replaceable and gave men safety and the freedom to achieve the look desired themselves.

EMMA ELIZABETH DAU

Alfred married Emma Elizabeth Dau in 1888. He was thirty-two and she was twenty Maybe this photo was taken at this time:

Emma is dressed in the style of the day, hourglass figure no doubt with a corseted waist as she gazes into her future with a determined tilt of her chin. Her hair is tightly curled at the front and pulled back into either a bun or pinned up plait.

Unlike the men who had barbers to attend to their needs, there don’t appear to be many ladies' hairdressers. Women had many home implements and potions and maybe sisters and mothers helped each other with their hair.

Young Emma’s tight curls may have been created with curling irons. A curling iron consisted of a metal rod that was held over a flame or burning alcohol to heat it, before wrapping the hair around it. Hey presto, curls!

Later in life, Emma wore her hair in a more relaxed style, loosely pulled back from her face and pinned up into a bun at the back:

When this photo was taken, the height of fashion for women was to wear their hair with more volume at the sides. This was created by using clumps of hair leftover in combs and brushes, to pad out the sides. Emma would not have gone to these lengths in later life, but on her dressing table she would have had a brush, comb, hand mirror and china box, with a lid for the collection of hair caught in brushes or combs. We can remember our grandmother, Alfreda, also having these items on her dressing table. She wore her hair long all her life. During the day it was loosely tied back in a bun, brushed out at night, and the ‘ratts’ collected from the brush and placed in the china box. She then plaited her hair into a loose, single long plait and was ready for bed.

NINE DAU SISTERS

Emma Coates, was born Emma Dau. She was one of seventeen. The first nine of these were girls.

We have three amazing little photos of some of the Dau children. We have spent a long time staring at these images, noticing little details, wondering about the lives of these nine little girls.

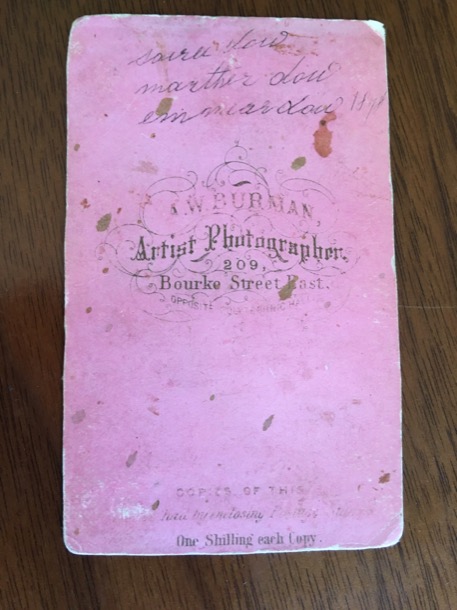

The first question we had was, "Were the three photos taken at the same time?". There is such a family resemblance, we weren’t sure at first whether they were different people in the three photos. The carpet gives away that they were taken in the same studio. On the back of one of the playing card sized photos, we see “one shilling per copy”. For context, at that time, a shilling was more than a day’s wage for a working man.

It seems most likely that the three photos were taken on the same day, and they are the nine oldest children, all daughters, of Joachim and Martha Dau, our great, great grandparents.

The photo of the three eldest has writing on the back:

The fact that Martha is misspelt as “marther”, and that no capital letters are used, might be a clue. It was not our mother Alice, nor her parents. None of them would have made such a basic spelling error! The surname is listed as “Dow”.

If those names are correct, then these are the three eldest Dau children. Standing is Sarah, the eldest. the other two are Martha, known as Mishi, and Emma, our great grandmother.

Thanks to the Wandong Historical group, we have the details of nearly all the Dau children.

The next three girls are Bella, Jane and Sophia, followed by Alice, and two others, possibly Annie and Nance, although some sources have Annie and Nance as the same person.

There is no date on these photos, but there are nine girls. The nine first Dau children, all girls were born between 1866 and about 1878. This puts the date of the photos at about 1880, with Sarah, the eldest, aged 14 and the youngest aged 2.

The girls’ father, Joachim, had spelt his surname, Dau. We don’t know the exact date they changed it to Dow, but Frederick enlisted to fight in the Boer War as Dow in 1901, and Arthur, who became a professional soldier, changed his name by deed poll to Dow. The same anti German sentiment that caused the British Royals to change their surname to Windsor from Saax Coburg was no doubt responsible. And yet the Dau spelling persists alongside the Dow spelling, right up until 1929, when Sarah, the eldest wrote about her childhood. Our mother and aunt did not even know about the Dau spelling.

The photographer is listed on the back as Burman, 209 Bourke St Melbourne. The building is still there. This is what it looks like today:

There are a number of old photos by Burman available on line, with that tell-tale carpet visible in some. This one, “Portrait of a Lady”, which uses the same chair as two of our photos, is from C1865.

We picture the little farm girls, in their new dresses, in the big noisy city. They would have come on the train, to Flinders Street from Wallan, and walked the three city blocks to the studio.

The city streets would have looked like this:

Their hair would had been in rags overnight. The curls in Sarah, Martha and Emma’s hair have been successful; the others less so. All of them have a ribbon holding their hair back from their face.

The dresses are interesting. The same fabric and pattern seems to have been used for the three eldest girls. Who made them? The next three also have a similar style. All have sturdy boots and frilly pantaloons. These outfits would have been worn to church on Sundays. Did they wear them for the train journey, or change at the studio?

The only other girl, born in 1887, preceded and followed by the seven boys, was Ethel. She wrote diary entries, still held by the Wandong Historical group. Ethel wrote about the boots, which are such a feature of these little girls’ photos. “the rough track across the paddocks and hills, two miles to the little school at Wandong. In wintertime, we had to cross many flooded gullies. We wore strong boots and I was often peeved, as I compared my strong shoes with the dainty ones worn by the other girls at school.”

It was quite an expense to provide boots for so many children.

Our appetite for finding out more about this family is well and truly whetted. We plan further exploration, including an excursion to Wandong.

THREE HOLM SISTERS

These three young women, probably photographed just before the first world war are (left to right) Alfreda, Beatrice and Berta Holm. Alfreda, our maternal grandmother, was the oldest of the three, perhaps just twenty at the time. The three sisters have their long hair swept back in gentle waves, to a loose bun or twist at the back.

We wonder whether they did the white work on their shirts? We know that Beatrice and Berta spent time working in Finders Lane, doing the white embroidery known at the time as “white work”. So much we can only guess at.

They all gaze into the distance: Alfreda with a determined steely gaze, Beat with a quizzical half smile and Bert’s beautiful eyes not quite hiding her vulnerability. We can only guess, as they gaze into a future where world war is imminent.

Alfreda wore her hair long all her life. We can remember her brushing her hair at night and putting it into a long plait.

TWO COATES SISTERS

It’s hard to be a younger sister, but our mother Alice, was the fairly plain younger sister of an extraordinary beauty.

She didn’t have to deal with social media, but, when she was growing up in the 1930s, feminine beauty was important for girls.

Alice was an intelligent and able scholar, and, thank goodness, this was highly valued in her family. Her mother, Alfreda, had made sacrifices and fought for her own education. For their later secondary school, the girls were sent, at huge expense, to a city based secondary school, all the way from Croydon.

Only the wealthiest or most determined families sent their girls to school, after the age of fourteen. At McRobinson Girls’ High School, Marge and Alice were taught by, and shared classes with, the very brightest and best: future women scientists, lawyers and doctors, who would pave the way for our own generation.

But, from her school reports, we see that, while she held her own on the whole, Alice was not exceptional in that auspicious company. And she was crippled, probably her whole life, by a sense of inferiority.

And it is in their respective hair cuts from that time, that we see how the contrast between the two girls was accentuated.

When I stare at those grainy old photos, at Marge’s lush locks, and Alice’s blunt, unfashionable short bob, and straight fringe, I cannot help but ask “Why?”. Why did Alfreda allow her younger daughter to wear such an unflattering style. Why was the difference in feminine beauty accentuated and underlined so prominently by the two hairstyles? How might Alice’s life have been different, had she been encouraged to make the most of her looks, as well as her brains?

Even as they began working life, both at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory, in 1939, the difference remained. Here Marge is on the far right, and Alice on the far left. Alice is nineteen and Marge twenty-one. But the choice of hairstyle reflects very different attitudes about their appearance:

THE VICTORY ROLL

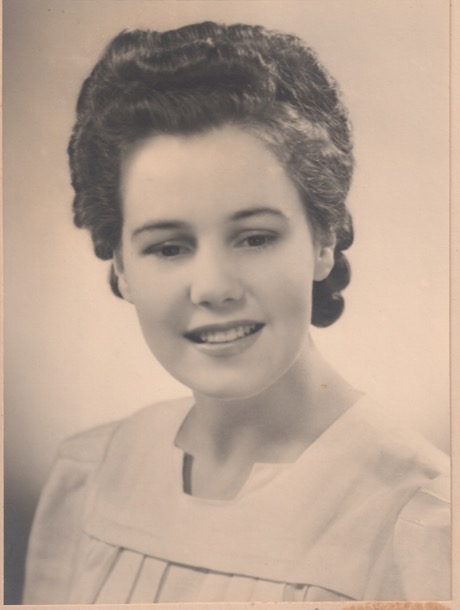

These two studio photographs of Marge are portraits of a beautiful young woman, but what does the hair tell us?

Here, a younger Marge still has very long hair, worn up now, as befitted a young woman who was no longer a child. Pretty curls and barrel curls were the look, and Marge had beautiful, wavy, very cooperative hair and was able to construct ‘the look’ very successfully.

An older Marge, maybe just twenty, posed for this studio photograph as a young woman of the war years, in the “hottest” style of the time. This photograph shows a confident young woman with a job, and presumably many admirers.

During the war, particularly during the Battle of Britain, the ‘Victory Roll’ evolved as a very popular and flattering hairstyle. The style was based on an aerobatic manoeuvre performed by pilots to signify victory. The planes would spin horizontally in celebration. The ‘Victory Roll’ hairstyle would have been difficult to execute, so hours of practice and experimentation was required. The style has stood the test of time, as it is still popular today in ‘retro’ dressing. There are many YouTube videos available with full and detailed instructions.

‘THE SET ‘

After the second world war, women’s hair fashion was dominated by ‘the set’, often a weekly set. Some women did their own at home, but others, such as our mother Alice, went to their local hairdresser.

The set involved a headful of rollers, tightly wound on wet hair, then dried under a hood dryer. This often took almost an hour, so there was time to read or chat.

Through the ages, and the generations of our family, both sexes’ hair styles have been influenced by the fashion of the day. We have all had cuts, or not. We have curled and permed and coloured and bleached, with varied results.

Today, people are not rigidly restricted to one style, as they were in the past, but have any options.

The lyrics from the musical Hair says it all: .

‘Gimme a head with hair

Long beautiful hair

Shining, gleaming,

Streaming, flaxen, waxen’

Auntie Bert, a "sterling character"

These three young women are our grandmother Alfreda on the left, with her two younger sisters, Beatrice in the middle and Berta on the right.

Alfreda’s set jaw and determined look reflect her independence and demand for an education. I fancy I can see both the rebel and the farmer in Beatrice’s broad face. But look at the gentle, faraway, passive prettiness of Berta. What experiences are already clouding her young face?

About ten percent of the whole of Australia’a population, the country’s young, fit men, set off to war in 1914. More than half of them were killed, gassed, wounded or taken prisoner. There was no such diagnosis as “post traumatic stress”, but we can extrapolate from the modern experience of returning soldiers.

What happened to the equivalent ten percent of young women, who, in different circumstances, would have been marrying them and having their babies?

Our Auntie Bert became one of the many “maiden aunts” of that very specific generation. The family lore is that she “had opportunities” to marry but “chose to stay in the bosom of her family”. We do not know what the reality of her young life was. Had she been a boy, she would have been one of the 417,000 men who enlisted. One would presume that virtually all the young men she might have had a romantic interest in… brothers of her friends, boys from church, at work, on the train, in her neighbourhood… nearly all would have been absent for four years from when she was 18 until she was 22.

Berta Holm was born in 1896. Her childhood and early adult life was spent in St Kilda.

The family story is that Berta and Beatrice unlike their older sister, Alfreda, did not hunger for an education.

Alice and Marge said this in quite a disapproving tone, which made us wonder about the accuracy of the statement, that Auntie Bert left school at Grade 4, declaring that she would prefer to help her mother at home. In Grade 4 she would have been nine or ten!

At the time Victoria was a progressive state and proud to be the first Australian state to create a system of free, secular and compulsory education. This legislation introduced in 1872, required all children aged 6-15 years to attend school unless they had a reasonable excuse. Schools were built, and a system of inspectors employed to enforce compulsory education. Fines for non-attendance were five shillings and increased for further offences. Did Auntie Bert leave school at the tender age of nine or ten? We think it more likely that she attended a State school, maybe unwillingly and, after trying a private school for young ladies, left at the age fifteen. Their disapproval of the lack of enthusiasm for education, compared to their own mother’s, probably colours the story about their aunt. The view of Auntie Bert we were brought up with, was that she was good with her hands, but, to soften and elevate this statement in true Holm fashion, it was followed by, she was a superb craftswoman and much in demand: not academic but exceptional.

Some time after she left school Berta went to work in Flinders Lane.

At that time Flinders Lane was the centre of the ‘rag trade’ where many Jewish firms had their businesses. Amongst them was Slutskins, for whom both Berta and Beatrice worked doing ‘white work’. Whitework embroidery is the general term for hand embroidery worked with white threads on white fabrics. It is one of the most elegant and timeless styles of embroidery and was used on underwear, night gowns, table linen, handkerchiefs, baby bonnets, christening gowns and many other small items.

After some experience in this area Berta became forewoman, in charge of a group of other women.

We only have Alice and Marge’s childhood recollections from which to piece together Berta’s life.

In early 1925, when she was twenty-nine, perhaps moving away from her parents’ home for the first time, she left her job, probably that responsible position as forewoman. She went, for an unspecified time, to the country, to help her married sister with a toddler and a baby, and to help serve in her brother in law’s hardware shop.

Alfreda had given birth to Alice, our mother, in 1923. She had had a terrible time, alone, during her first delivery, resulting in the death of the baby. We don't know anything about Marge’s birth or the subsequent few years, except that they were quite near to family help. But when Alice was fifteen months old, Alf and Alfreda moved to Bacchus Marsh. Alfreda was “weak from the birth”. The descriptions of her crying, while scrubbing the floor and having to spend whole days in bed, apparently requiring the help of her unmarried sister, makes us think of post natal depression.

Alf too had what we would today call “mental health issues”. He was a gentle, quite scholarly person, and the business venture in Bacchus Marsh, on the eve of the Great Depression, took a toll on his health. It is no wonder Marge and Alice remember Auntie Bert as a tower of strength and support.

In 1928, the old dry house they had been living in caught fire. At the top of the burning staircase were the little girls in their nighties, Alf sedated, because he was in the midst of a “nervous breakdown”, Alfreda, reportedly trying to find her stockings, and Bert, who carried Alice down the stairs. Marge was carried down by her father, finally awake.

The destitute family were taken in by “the Pierces”. Nell Pierce was a lifelong friend of Auntie Bert. Did they meet there at Bacchus Marsh? We don't know.

The family stayed on for at least a year in Bacchus Marsh, but Berta moved back to Melbourne, once again moving in with her parents, probably her only option.

Now in her early thirties and unmarried Berta must have turned her attention to a job. As far as we know this is when she decided to start her own business as a dressmaker. At first she worked from her bedroom, building her business and reputation.

The business was eventually profitable enough to allow her to move to premises in Riversdale Road, Middle Camberwell and then to Burke Road in Camberwell, just over the junction.

I can remember the junction premises quite vividly. It was one big room on the first floor. Big windows looked out onto Burke Road, letting in light and sunshine that fell on the big work tables. Several dressmakers dummies stood in the corner where the fitting room was screened by curtains. It seemed a very busy place.

The big tables, that dominated the space were covered in the paraphernalia of dressmaking. There were several sewing machines, many reels of sewing cotton, several pairs of big dressmakers shears, other dressmaking scissors and many tins of pins. Rolls of fabric and garments in various stages of construction took up the rest of the table space. Another woman was sewing at the table, presumably an employee, so business must have been good. We were probably there for a fitting, as Auntie Bert made ‘good clothes’, for Mum. These beautifully tailored clothes were worn to Church and were for special occasions, including weddings:

She also made us beautiful clothes including these woollen dresses:

Auntie Bert had an account at Ball & Welch, a prominent department store in Finders Street, Melbourne. She needed an account for her business and a reliable source of good quality fabric for her clients. Its four floors occupied one third of the total block and stretched between Flinders Street and Flinders Lane.

Its many departments included gloves, umbrellas and handkerchiefs, fabrics, furniture, china, millinery, furs and corsets. At one time twenty-six assistants were devoted to the sale of lace alone.

Members of the family were generously given access to Auntie Bert’s account, making it possible to buy items on account and pay later. This was very useful at times, as there was no such thing as Credit Cards. At the end of the month, Auntie Bert sent out letters to all those who had used the account, and we reimbursed her by cheque. This was probably quite a task, not only the arithmetic, but also the sending out of all the individual letters.

I can remember enjoying trips to Ball&Welch. The lifts were staffed by attendants in uniform who recited the list of items available at each level as the lift rose between floors. Parcels were wrapped up in brown paper and string, on huge wooden counters. The expert shop assistants were reserved, formal and a little forbidding to a young child. The exchange of payment was quite a process. The shop assistants' job was to serve the customers, not handle the money. When payment was made, it was placed, with the hand written docket, in a metal canister that went shooting on wires across the departments and then upstairs to the Accounts Department. The docket was checked, change inserted, a receipt written and the canister whizzed back from whence it had come. Transaction complete.

The cash-ball system worked reasonably well, but the rails were intrusive and the interior layout of some stores did not allow certain counters or departments to be connected by inclined tracks. The ingenious Lamson then hit upon the concept of the “aerial railway” and set about tinkering with a gondola-like design, which became known as the wire-line or cable-carrier.

By the late 1880s, sales staff could secure cash inside a small wooden jar or canister, suspended by wheels from a taut wire that ran overhead from the sales desk to the cashier’s station, which was typically a cage-like booth situated in the center of the store. By tugging firmly on a spring-loaded cord or lever known as the “propulsion,” the canister would be catapulted along the wire, reaching its destination in mere seconds.

The cashier could then “return fire” with change and a receipt. Cashiers who worked in booths on levels above the sales floor could simply release the canister and let gravity return it to the appropriate counter.

Ball and Welch closed its doors in 1970, the end of an era .

Berta’s sister, Beatrice had taken up dairy farming in the early 1950s, near Cockatoo, in the Dandenong Ranges. The bulk of the work was done by her husband, and three sons. In 1955, the wife of Rob, the middle son, died, leaving a baby daughter, Julie, to be raised by her grandmother.

Into the breach stepped Berta. She moved into a small bedroom in the farm house, and became a second mother to Julie. We remember her room. It had been part of the farmhouse verandah, and the whole room was about twice the size of the single bed. It was neat, sparse and dark.

Our memory of Auntie Bert at the farm is solely inside the farm house. Unlike Auntie Beat, who mucked out the pigs, wearing layers of old jumpers and a woollen beanie, Auntie Bert was always nicely dressed. We remember her in well-cut woollen skirts, stockings and heeled court shoes, with classy jumpers and cardigans. We picture the two of them in the kitchen, both wearing aprons, turning out scones and cakes on the wood stove. Auntie Bert became a permanent and valuable member of the family, looking after the “boys” and Julie.

While her main home and focus was life at the farm, Auntie Bert continued, as she had her whole life, to be the family helper and nurse. She had looked after both her own parents in their final years, and she came to live with us to help out with her elder sister: our Nana, Alfreda, who had dementia. We remember her as a quiet unobtrusive presence in our home. A few years later she came again and helped with Alf, our grandfather, in his final weeks.

So Alice saw first hand, the skill and care of Berta’s nursing:

Apart from staying temporarily with other members of the family, usually to help out during family crises, Berta lived there at the farm, until her death in 1976, aged 80.

Alice reflected on Berta’s death and the simple generous life she lived:

From left to right, Nana, Auntie Bert and Alice: