Women's Work

Like women throughout history, most of the women in our family have had the primary job of parent and homemaker. Those homes range from simple pioneer cottages to majestic residences with grand staircases and sweeping verandahs. Nearly all of those women have also done paid work. And some of those who have not been specifically employed, have had supporting roles in their husband’s careers. Some jobs have been done by different family members across different generations.

None of our women have had traditional men’s careers, but, across the generations, we have covered a wide range:

AGRICULTURE (Dairy maid, Famers’ wives)

HEALTHWORK (Doctors’ wives, Aide, Occupational Therapy Assistant)

HOSPITALITY/TOURISM (Publican, Office Administraion, Horse Trail Guide)

RELIGIOUS SERVICE (Lay Preaching and other good works, Nun)

ADMINISTRATION (Postmistress, Sales Administration Supervisor, Office Administrator)

THE ARTS/CRAFT/DRAFTING (Whitework, Semco and Dressmaking, Drafting and Drawing Office, Drafting, Drawing and Card production, Art and Craft Activities for At Risk Children, Set Design and Construction, An Artist in the Hills)

RETAIL (Grocer, Checkout Chick)

SCIENCE (Laboratory Work)

EDUCATION (Teacher)

AGRICULTURE

Dairy Maid

Our paternal great, great grandmother, Catherine Bourke, née Kelly, worked as a dairy maid in Limerick before marrying Michael Bourke, and emigrating to Australia, in 1839. When they arrived in Melbourne, their first job was managing a dairy farm in Moonee Ponds. Catherine’s knowledge and skills no doubt influenced this decision.

The “famers’ wives”

A recent (2022) Guardian article tells us that, until 1994, women could not list “farmer” as their occupation on the census form. Instead they were viewed as “non-productive silent partners”. Even today, when 49% of real farm income is contributed by women, our image of an Australian farmer is almost entirely male. This puts “farmers’ wife” in this exploration in a particular light.

Another interesting aspect of these women from our family history is the divide between the wealthy squatters and the ordinary people of the land.

Martha Rye, the “poor little thing”, whose story we told in the June 2016 post, was a “farmer’s wife”, as was her mother, Elizabeth. Both of these women had very large families.

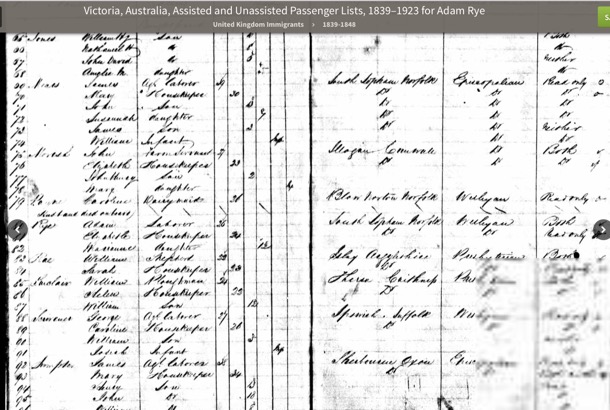

Elizabeth, our great great great grandmother, had eleven children. We can work out quite a bit about Elizabeth from a newspaper story, written about her husband, Adam’s life. She had worked in service, as a housekeeper, before she and Adam emigrated to Australia, in 1848. She could read, but not write.

They grew potatoes and onions, first on a rented farm near Geelong, then on two acres in Broadmeadows. The whole family would have been involved in the farm work, especially at harvest and market times.

We know that Adam not only worked as a labourer on neighbouring farms, but also spent time away trying his luck on the goldfields. It would have fallen on Elizabeth and the children to keep things going on the farm.

Martha, Elizabeth’s daughter, was married to Joachim. They would have had long days on the dairy farm, Heather Farm, near Kilmore. We learned a bit about her from her daughter Sarah, born in 1866. We wrote about this in August 2016. Sarah wrote with sentimental nostalgia about milking the cows, Blossom, Peggy and Strawberry; feeding poddy calves; working the separator; and rearing seventeen children. But between the lines, one can see the massive workload.

Around the same time, our paternal great great grandparents, John and Johanna McCormack, (later called Joan) acquired their 15,000 acre grazing property, Balham Hill, fifty kilometres to the west. So, in a sense, Johanna was also a “farmer’s wife”. But what a different life! John, a Justice of the Peace, and community leader, had staff to attend to the farm. Their four surviving children all went to boarding school in the city, for their secondary education.

Two generations on, Johanna’s granddaughter, our Auntie Tish, also married a farmer, near Warrnambool. Matt Rae was probably more of a hands on farmer than John McCormick, but he, too, was considered a grazier, and Tish’s life did not run to milking cows and feeding poddy calves.

Around 1950, close to the time Tish became a “farmer’s wife”, our mother’s aunt, Beat, and her husband Bill, sold their Surrey Hills grocery and bought land for a dairy farm in Cockatoo. The activities on this farm were similar to those at Heather Farm, a hundred years earlier: milking, feeding calves, working the separator. The difference in their lives is technological. An electric milking machine and separator, tractors, hay bailers, meant that they ran a dozen cows instead of three. And they had three grown children instead of seventeen. Nevertheless, they all had to work hard to make the farm pay enough to support them all. We wrote in detail, in our November 2017 post, about our childhood visits to this farm. There we described Beat’s pigs. This was her major farming contribution. She was not just a “farmer’s wife”, but actively involved in the decision making and physical work of the farm.

Auntie Beat

HEALTHWORK

Health work does not feature much among the women in our family. There are no doctors or nurses, that we know of.

Doctors’ wives

Our grandmother, Grace, and her daughter in law, Joan, were “Doctor’s Wives”. Wealthy, well connected, pillars of society, these women had no real job. In both cases, their husband’s surgery was within their house, but they were not required to deal with actual patients.

Among the women in our family, there are a few cases of unskilled health work.

Aide

Like so many women, our mother, Alice, “went back to work” when her youngest child was about ten years old, in 1966.

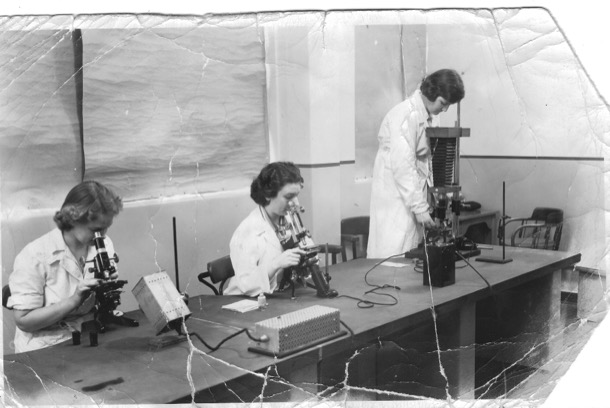

The only job she had had, since leaving school aged seventeen, was the wartime munitions work she had done at Maribynong, which today would have been called Lab Technician.

What skills did she have to draw on, apart from housework and parenting?

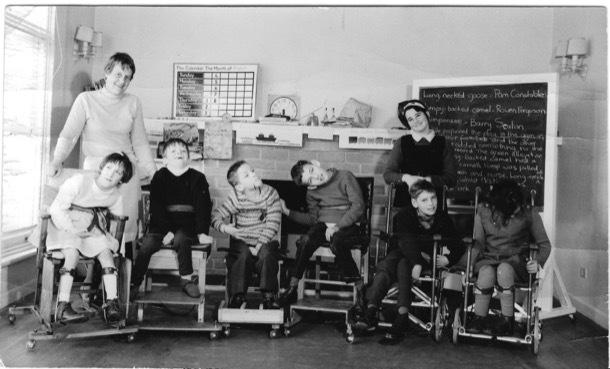

So her job as an “aide” at Lady Herring Spastic Centre was a low paid, unskilled one. She was assigned, with one other carer, to a “class” of Cerebral Palsied kids roughly the same age, none of whom had the ability to speak, and many of whom could not feed themselves. This was before the days of Communication Boards, so even the most able kids could not communicate much.

I, too, had a job at Lady Herring, after I finished school, and before I began the university year.

The centre was in Malvern, and Alice, and I, for the few weeks I was there, travelled by tram, along a very familiar route, down Riversdale Road.

There were a few qualified staff at the centre, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, but the program, such as it was, seemed to be up to people like Alice to devise. With the exception of the bus drivers, the whole staff, including the boss, was female.

The kids commuted on a special bus, and spent the whole day at the centre. Much of the time was filled with dealing with their physical needs, but there were excursions, shopping trips, walks around the neighbourhood, music sessions, and a memorable overnight “camp”. Although low status and poorly paid, it was stimulating, challenging work.

Alice with her "class"

Occupational Therapy Assistant

On the strength of my experience at Lady Herring, I did two other holiday stints as an OT assistant.

I worked with our OT friend Rikki, at Fairfield Infectious Diseases hospital for a little while. This was before HIV made it such an important place. My memories of Fairfield include the beautiful historic buildings; dozens of beds in a row, in the children’s Hepatitis ward; and the iron lung ward: people who had contracted polio as children and spent their life lying inside huge metal chambers that helped them breathe.

My job was mostly helping tidy up the activity room, and working in the ward with the Hepatitis kids: mostly bringing them things to do.

Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital

And then, during another long uni holiday, I worked at Montefiore (Jewish) Aged Care in St Kilda. It was perhaps 1970. Most of the Occupational Therapy “workers” there were volunteers: generally well off middle aged Jewish women doing their bit. One of those volunteers, who I remembered just as Mrs Hayman, later became Sue’s mother in law.

In my memory, the whole staff, except the doctors, were women.

In our centre, where the patients came to us, we ran activities like singalongs, bingo, games etc.

Many of our patients were post war immigrants from Europe, and some had been in Nazi concentration camps. It was the year that Melbourne emergency vehicles changed from sirens to “nee naw nee naw”, the same sound the SS vehicles had used in wartime Europe. When we heard the distant sounds approaching along St Kilda Road, we needed to be aware of some patients’ reaction.

I remember being told that that gentleman with his trousers barely held up with string, had been one of Melbourne’s top barristers. I still have the book called “Favourite Jewish Songs”, piano accompaniments I used for the singalongs I accompanied.

HOSPITALITY/TOURISM

Publican

Catherine Bourke, in her new home near Pakenham from 1844, helped with the establishment of Minton’s Creek Run, the farm in the Toomuc Valley, that they bought with another family. But in 1850, they bought the Latrobe Inn, on the main Gippsland Road, in current day Pakenham. Catherine moved out of the slab hut up the Valley, with her seven children, and became a publican. The inn became known as Bourke’s Hotel. Michael was still very involved with the family, and they had another eight children, but it was Catherine who ran the hotel.

As well as a stopping place for travellers, Bourke’s hotel was the local post office, and a hub for the community.

Catherine Bourke

Horse Trail Guide

Catherine’s great, great, great, great, great niece Eliza, one hundred and seventy years later, also moved to the country to start a new job in tourism. Seeking a change from office work, Eliza moved to Mansfield to work for Hidden Trails by Horseback. This company runs trails in the Victorian High Country and also at El Questro Station in the Kimberly.

In Eliza’s own words her job entailed the following:

Up at the crack of dawn. Run the horses in. Feed the ones we are working that day. Brush and saddle the horses needed for the rides.

Determine the guests riding experience, match to a horse. Sign indemnity forms, Go through basics (stop start turn etc) and then lead the ride out, float in the middle of a big group, or tail the group at the back.

We go out on four rides a day:

*AM 2 hour ride (around the station)

*Kids intro ride (around the paddock)

*1 hour loop (around a different part of the station which includes the deep moonshine creek crossing)

*PM 2 hour ride (incorporation of the 1 hour loop with a look out stop where we would take a pack horse with drinks and nibbles and tie the horses up and have a sit down)

In between those rides we feed lunch to the horses working. Then back to the stables in the afternoon, Unsaddle, wash down and tip out the horses. And then do it all again the next day. Shuffling them around in different paddocks so we could keep them all in work.

There was 40 horses total.

Long days. Great experience.

Eliza at El Questro

RELIGIOUS SERVICE

Lay Preaching and other good works

Both our mother Alice and her maternal grandmother Emma Coates (née Dau) were staunch protestants and indulged in a little lay preaching and good works.

Emma Dau, one of seventeen children, was married to Alfred Coates, who was a Wesleyan Methodist Pastor. Emma’s married life consisted of raising a family, and her duties as the Pastor’s wife. Family stories tell of her devotion to these duties and of her riding around the parish on a push bike.

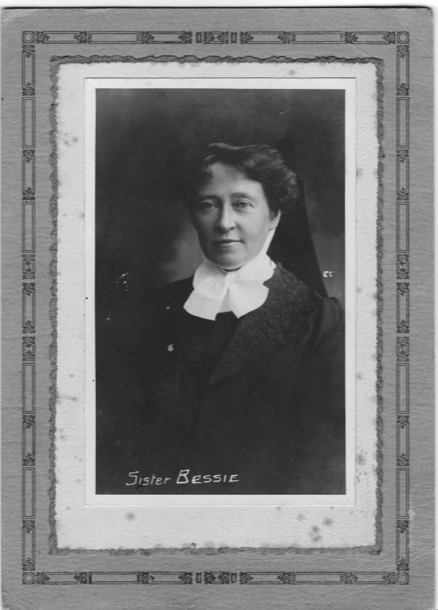

At some stage in her life, when our mother was still a child, Emma also became a Home Mission Sister and was known as Sister Bessie. As a Home Mission Sister, Emma wore an impressive uniform, that is described vividly by our mother and Auntie Marge, who as children were very impressed by this formidable woman. Here they are discussing her:

Sister Bessie

Sister Bessie worked at the Methodist Home Mission in Brunswick Street Fitzroy, in the 1920s and 30s. Sister Bessie’s work with the ‘fallen women’ and the poor, in the slums of Fitzroy was also vividly remembered by Marge and Alice. Sister Bessie’s good works involved anything from delivering babies to rescuing unmarried mothers. All of this was carried out ‘in the slums’ and in ‘poor, dirty houses’. One story has it that Sister Bessie once took off her own petticoat to give to a poor woman who did not have enough clothing.

The slums of Fitzroy were indeed slums, with a reputation for dirt, filth, disease and crime, a fearsome place. Streets were unpaved, there was no running water in many of the crowded and small weatherboard houses and children often ran barefoot.

So bad were the Fitzroy slums, that in the 1950’s they were demolished and the population was moved to the Housing Commission Towers, still standing in Brunswick Street.

Slums in Melbourne

Sister Bessie also travelled within Victoria and Tasmania. She was lay preaching, called ‘deputation work’ and raising money for the Home Mission. Apparently she was a very good story teller and must have not only impressed her young grand daughters but also her audiences, as she regaled them with stories from ‘the slums’. So impressed was one small child, that she gave up her doll ,to be given to the poor children who had no toys.

Half a century later Alice stood in her grandmother’s shoes at the same pulpit of a small, now Uniting Church, at Jung in the Wimmera.

Alice was also doing ‘deputation work’ in a fashion, preaching about world poverty and inequality. She was also raising money for the Uniting Church’s fight against poverty. Alice mentioned that her grandmother, Sister Bessie, may also have preached here. Incredibly a member of the congregation remembered as a small child listening to Sister Bessie preaching and telling stories. She said,“She was a wonderful story teller.”

Jung Methodist Church

The Nun

We grew up with stories of a nun in the family but knew no details. With the assistance of Google, we now know that Frances Bourke, [1883-1964] Jim’s Great Aunt, joined the Presentation Sisters, probably as a young woman, and became Sister Magdalen.

Presentation Convent was founded in Windsor in 1873, after a request by the Parish Priest for sorely needed teaching staff at St Mary’s school.

We are intrigued about Sister Magdalen and her role. Was she a teaching Sister or did she have another role at the Windsor Convent? Did she spend her life in the Order? Watch this space, hopefully more to come.

Presentation Sisters

ADMINISTRATION

Administration is part of many jobs, often the least pleasant part; writing reports, managing co workers, attending meetings, communication, ordering supplies, keeping records. These tasks are familiar to many workers.

Postmistress

In 1859 Bourke’s Hotel in Pakenham also became the community post office, ten years after Michael had bought the license. He became the founding post master of Pakenham. After his death, in 1877, Catherine became the Pakenham postmistress.

Up until 1901, each of the colonies operated their own postal service. After Federation, they all merged to become the Postmaster Generals Department (PMG).

Cecelia,(Cissy), Catherine’s youngest child, who never married, continued the role after Catherine’s death in 1910.

The job of postmistress would have involved taking sacks of mail to and from the Cobb and Co coach, later the train, and sorting it for people, who would come in to collect their mail.

Over time, the job of post mistress also included a savings’ bank, money order office and telegraph station; quite an important role in the local community.

Sales Administration Supervisor

But for a proper administration job, Tessa is our woman. Her job at Kenworth Trucks is to project manage the outfitting of each truck. She manages a team of people who put 22 trucks per day together, to the specifications of each customer. Keeping all the balls in the air, making sure everyone is gainfully employed, smoothing relationships with customers and between workers, maintaining records, supervising departments. It’s a very large and stressful job.

Office Administrator

Another organised young woman is Eliza who has also worked in office administration, at Nautilus Training and Curriculum, the company founded by her dad, Ian.

THE ARTS/CRAFT/DRAFTING

Whitework, Semco and Dressmaking

Three of our women worked in the textile industry, a generation apart. Both Great Aunts Bert and Beat and our Auntie Marge were involved in the embellishment of textiles with embroidery, and in dressmaking.

In our post on Auntie Bert, ‘A Sterling Character’, in March 2019 we explored ‘Whitework’. Whitework embroidery is the general term for hand embroidery worked with white thread on white fabric. It was used on many household items from babies’ bibs and tea towels to under clothes. Bert and Beat who, as young women, worked in this industry, probably worked in Flinders Lane. At this time it was the centre of the “rag trade”.

Auntie Bert, being unmarried, needed to continue in the workforce, but also be available to help her elderly parents with whom she lived. A talented and resourceful woman, she started a dressmaking business, working from home. Although self taught, her reputation for fine tailoring and expertly fitted ladies’ wear soon spread amongst the ladies of Camberwell and Surrey Hills. As her clientele increased and business grew, she had to move to bigger premises, and Bert leased space for a workroom and office in Riversdale Road Camberwell. This business is also described in our post ‘ A Sterling Character”

Drafting and Drawing Office

Our Auntie Marge worked in a number of drafting and drawing offices during her working life. After her short stint teaching, Marge began work in a drawing office in Collins Street, and then, during the war, moved to the drawing office at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory where Alice also worked. In 1941 Marge moved again, this time to the drawing office at ICI.

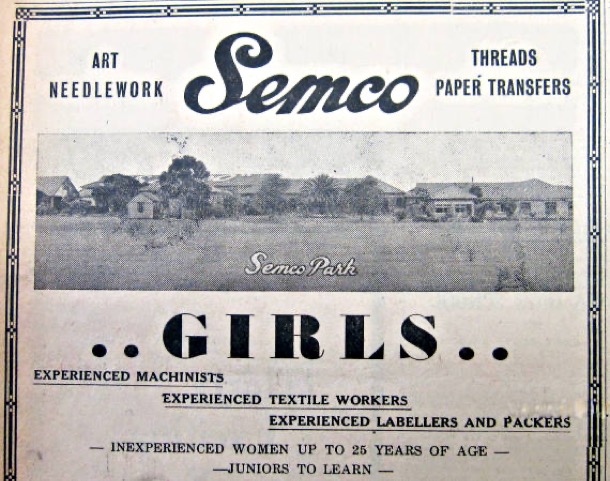

Later in life, Marge used her artistic talents at Semco, designing patterns for embroidery transfers. The designs were created as line drawings and printed onto tissue paper transfers, to be sold to women to embroider for items for the home, or as gifts. The transfers were ironed onto cloth after which the item could be embroidered accurately following the design. Margaret and I can remember embarking on an Semco embroidery project that I don’t think we finished.

Semco Workroom

Typical Semco Embroidery

Design subjects were flowers and animals, both European and Australian, cute houses, toys and even landscape scenes. Amongst the many items destined for embroidery were doilies, tablecloths and serviettes, tray cloths, handkerchiefs, babies’ outfits and children’s clothing.

Margaret and I can also remember visiting Auntie Marge at Black Rock and seeing her designs on a big drawing board. A working mother was a novelty for us, as our mother did not work outside the home.

The Semco factory and workshops located in Semco Park, Black Rock, was quite a progressive company and treated its employees well. They paid award wages to women, and provided recreation facilities for the staff, including six and a half acres of garden and lawn for their enjoyment. It was a large employer, as not only were the designs created and printed, but the embroidery cottons were also spun and dyed.

Marge worked for Semco as a part time employee, and at the same time studied Interior Design at RMIT. Both were unusual. For many women of her era, part time work outside the home was difficult to find, even once children were at school. Marge was fortunate to have Semco in her area and for it to be accessible on public transport. This allowed her to work there for many years, while pursuing her life long interest in further study.

Drafting, Drawing and Card production

Marge worked in a number of drafting and drawing offices during her working life. After her short stint teaching, Marge began work in a drawing office in Collins Street and then, during the war, moved to the drawing office at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory where Alice also worked. In 1941 Marge moved again, this time to the drawing office at ICI.

In between jobs outside the home Marge, like her Aunt Bert, started a business from home. Using her artistic skills and her design experience at Semco, Marge launched a greeting card business. She designed and screen printed the cards, packaged them and sold them to shops specialising in handmade original work.

Art and Craft Activities for At Risk Children

From this heading, it is obvious that this position could be fraught with difficulties. As a nineteen year old I was blissfully unaware of the worlds these children came from. Orana was a Uniting Church children’s home for at risk children and ‘orphans’. I remember mostly a group of cardigan and jumper clad children in skirts and shorts, traipsing into a linoleum floored space to participate in whatever I decided to do. I don’t remember anyone checking the activities, or that I had to run them past any of the staff. Some of the activities were very, very messy, but the children willingly helped me clean up. The confronting and difficult part of this job was not the behaviour of the children, but the heavy prevailing air of sadness in that place.

Set Design and Construction

Lois learnt woodworking from her dad. Together with her design and craft skills, she developed her “Top Props” business, designing and creating stage props. For instance, Deirdre’s Tappers’ concerts would not have been the amazing spectacle they were, without Lois’s colourful props.

An Artist in the Hills

Through her meticulous fine drawings and paintings Katherine explores a fantasy world inhabited by little creatures and characters, who are at home with spiderwebs and toadstools or nestled under gnarled old trees . Working from her house and studio in the Dandenongs, she is pursuing her interest in children’s book illustration.

RETAIL

Grocer

Our Great Aunt, our grandmother’s sister, Beatrice Morris (nee: Holm) owned a grocer’s shop in Maling Road, Canterbury, for a number of years. Bill Morris had previously worked at Lawson’s Grocer in Middle Camberwell , so having experience, this was a logical move. We are not sure how long they were in Maling Road but presumably Auntie Beat helped in the shop as well as raising a family of three boys. It must have been reasonably profitable, as during this time they built a house in Balwyn, and then sold the business to buy the farm, Sefton Park.

“Checkout Chick”

Anna, Beatrice’s great, great niece, is the only other woman in the family who has worked in retail, and this too was in grocery shop: the Renaissance Supermarket, Hawthorn, in the 1990’s: it was a supermarket of course. At sixteen Anna was keen to have a part time job and earn her own money. Her position was ‘checkout chick’, working on the register, before scanning of prices using barcodes was all entirely automatic. For instance, the checkout chicks had to memorise the PLU code for all the individual fruit and vegetable items, and this had to be entered on the register, manually.

SCIENCE

Laboratory Work

After the horrific use of chemical warfare (gas), on the European battlefields during the 1914-18 war, many countries began to work on ways to protect their populations from gas warfare.

Australia began its own “Chemical Defence” research program in 1926 at the Munitions Supply Laboratories, in conjunction with Melbourne Uni. They developed and assembled “respirators”.

By the time the second world war began in 1939, scientists were well advanced in this work. In 1940, over half a million respirators were manufactured at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory, and more than 500 people were employed there.

Our mother, Alice worked there, in the microscope section, testing the penetration of gas that came through the filters. When she would describe this work, she would indicate tapping and counting as she stared down the microscope. She had studied Year 11 Chemistry the year before she started.

Alice, left, working at Maribrynong

EDUCATION

Teachers

At least five of the women, in four generations of our family, have been teachers, some primary, some secondary.

The earliest we know of is our Nana, Alfreda, who taught primary school, before marrying Alfred in 1916.

She had fought for a chance to continue her education after secondary school. There was not enough money for university, and so she went to Melbourne Continuation School, which later became Melbourne High School. Its focus was teacher training and thus, after two years, Alfreda became a teacher. Presumably she taught for about four years. Women had to resign from teaching when they married.

Our Auntie Marge, Alfreda’s eldest daughter worked as a teacher for a year, straight from school. She taught 50 five year olds at Balwyn North, as a “junior teacher’. She also went to RMIT three nights a week dong Fine Art, her real passion. She only lasted one year, having decided that she was not suited to teaching. Our mother, Alice, while not actually teaching, worked as a school librarian assistant for the last years leading up to her retirement.

The next generation is ours, and at least four of us worked as secondary teachers: Pauline for a few years, and Sue, Anne and I until our retirements. All three of us did our initial tertiary education, including teacher training, on “Studentships”, which provided free education and a small wage, in return for three years service, usually in the country. Sue went to Sale, Pauline to Portland, and Margaret to Moe. Sue and and I wrote about our first year teaching experiences in a post on October 28, 2015, filed under “Young Adults 1970s”

Sale High School

Of our own daughters and nieces, only Anna has taken on the mantle of teaching. She even completed most of a PHD in Education. Recently, in her mid forties, she has gone back to the English classroom in a secondary school, where she is thriving!

Such a lot of different job experiences, and yet, within relatively narrow parameters. No astronauts, truck drivers or plumbers.

And, it must be stressed, the most important job for almost all these women, over six generations and nearly a century, is that of parent and homemaker.

Heather Farm, Kilmore Junction ,1879

Three of the Dau children.

Fifty Years Ago at Kilmore Junction HEATHER FARM

In a lonely spot on the hillside, where the old cypress still lives and bends in the breeze, stands what is left of our once loved home, so loved in those old days gone by when a dear father and mother still lived to help us unravel life's tangled skein.

There the musk tree, mother planted, and cared for and loved—just beside the straggling remains of the lovely lilac trees; there the remains of the old gum tree where father sharpened his axe in its groove, and we children watched and wondered what difference it made; the path where the strawberries grew large and juicy on each side; the vines and the currants and gooseberry bushes—what tales they could tell could they speak. Father's pear tree, once laden with its golden store, now old and scrubby, still fading away.

The dairy house still stands, but the hum of the separator is silent. The stable, where Polly and Lofty enjoyed their hard-earned rest and feed, the cow yards: oh, what memories of Blossom, Violet and Peggy do those few remaining stone paths recall.

There is the old slip-panel, where father stood to welcome the children with smiling face when home on holiday: dear, gentle Dad, from whose lips we heard no unkind word; the wild cherry tree, where the boys carved their names, still there, the same beloved handwriting, although one sleeps in France and the other in Africa—duty nobly done.

The corner where the raspberries grew, juicy and red, at Xmas time; our favourite apple tree. How we loved to run down and see how many our thoughtful mother had saved for us, her wanderers. Memories!

Sometimes we wander back again to where the old home stood, and as we stand and think of other happy days gone for ever and gaze on all this, we seem to hear their loved voices again speaking to us, their children, although some of us are on the shady side of 60.

What would we give to live some of those old times gone by, and a kind word from father and a smile from mother? Seventeen of us—their children—were reared up to manhood and womanhood on the site of that once beloved home. The silent bush: no picture shows, no evening entertainments, just our books and our church on Sunday.

Oh, to live it all again. To once more call dear old Blossom, Peggy, and Strawberry home for milking. To feed again those poddy calves. To turn the old separator. To hear the voice again of our dear old teacher—who taught 13 of our family before he went to rest. To walk to the old church on Sundays and then home, where mother had laid the snow cloth with all things good for tea (and home made), and then go to the back paddock for wattle gum, where the pink and white heath grew, and wattle blossom bloomed.

Dear old home, we shall never see again. Only in our memory there will live that lovely past, which for us all, too soon, has fled and left only memories of other days. Some of us would love to live again at dear old Heather Farm.

Sarah Coles (née Dau)

McEwan Road, Heidelberg. 7/2/1929

The Poor Little Thing

Marge and Alice, with great drama, tell the story of our great, great grandmother whose name they do not know, and her subsequent marriage to Grandfather Dow, with whom she had eighteen children.

They had little factual information and their story is obviously based on stories told to them by their father. “That’s how the tale goes and the imagination boggles,” says Alice at one stage and indeed it did!

THE FAMILY TALE would have us believe that the our great, great grandmother, name unknown, met her prospective husband, first name unknown, at the Victoria Market. She was apparently a child of fifteen dragged off by a middle aged man to a poor farm miles out in the country of early colonial Victoria. The long and arduous journey into the night finished at Wandong where the poor little thing, ‘rolled up her sleeves and started milking cows straight away.’ She bore eighteen children and did much of the work, as her husband, a German immigrant from Bavaria, who was rumoured to have noble blood, sat behind the milking shed reading poetry. The poor little thing lived to 83 and grew very broad in the beam. Her husband as the tale goes died at 102 sitting up in bed singing a hymn.

The mind does indeed boggle. Was she a poor little thing? How much is ‘tale’?

You be the judge.

We also have a story extrapolated from FACTS provided by the Victorian Records Office, Ancestry Dot Com, Google, newspapers, shipping records and documents from England.

The ‘poor little thing’ was Martha Rye born in 1850 in Geelong in the Colony of New South Wales. The year after her birth in 1851 the Colony of Victoria was founded and separation from New South Wales was formalised.

Martha Rye was the first child born in Australia to Adam (1822 - 1924) and Elizabeth (1824 - 1901) Rye, recently arrived immigrants to the young colony.

Adam and Elizabeth emigrated to Australia from South Lopham in Norfolk, England in 1848. They had with them one child, Marianne who was a year old. Adam was twenty-six and Elizabeth twenty-four.

Here is the South Lopham church in which they were married:

We know from the shipping records that they sailed on the sailing ship The Berkshire, arriving in Geelong on October the third, 1848. Their occupations were listed as labourer and housekeeper. He could read and write, she could read but not write.

We know that he had indeed worked as a labourer on his father’s farm, but he had also had a stint as a footman in the household of Lord Randall, which is where he tasted a bit of Queen Victoria’s wedding cake, shared with the staff by Lord Randall, who had been a wedding guest.

When he and Elizabeth left for Australia, they sat down to a farewell dinner with thirty-two of Adam’s brother and sisters (from three different mothers).

Adam lived 102 years, and when he was in his nineties, his colourful life story was written up by an enthusiastic journalist for a local paper. Note his editorialising in the following extract about “treacherous blacks”.

The family settled near Geelong, where they rented a piece of land to farm.

“While here Rye went off one day to the store for provisions, and after getting his supplies started for home, but darkness overtook him and he lost the track. He wandered about for some hours, and at last came upon a party of about 50 blacks. He thought it was no use trying to run away so he had to stand his ground. The blacks took his supply of bread, cheese, tobacco and a bottle of rum away from him and divided them amongst themselves, never leaving him a bite. Towards morning he made them understand where he lived and they directed him to his home, but having found out where he lived they paid him a couple of visits at night time and carried off his potatoes - not any that came to hand but the biggest and best and potatoes were worth £30 a ton in those days. The blacks at this time were very treacherous. They would watch the mothers going away for water and would steal into the huts and carry away anything they fancied even occasionally stealing a baby, which was never seen again, the blacks having roasted it for the camp's dinner. After a time he left for Melbourne. While here he met the same tribe of blacks, who recognised him, although the years had passed in the interim.”

Martha, our great great grandmother, born in 1850, was the first of eleven of Adam and Elizabeth’s children to be born in Australia.

The family moved to Broadmeadows, where Adam worked as a farm hand, cutting thistles and maintaining fences, as well as farming a piece of land himself. The newspaper article mentions wheat, potatoes and onions.

Here is an extract about the Broadmeadows farm.

He had about 2 acres of and with a splendid crop of onions on it. He and his family had been working hard getting these ready for market and left them in heaps about the ground ready to bag next day. To their utter astonishment, on going to finish their work they found that somebody had done the work for them, and had carted the lot away. There were from 10 to15 tons altogether, and this at £8 a ton was no small item to lose. However, he made up a bit on his crop of potatoes, which, although a light one, brought in £30 a ton. Butter was then 3 shillings a pound, bread 1 shilling a loaf, and a bag of flour as high as £5 a bag. This was owing in a good measure to the high rate of cartage.

This was the height of the gold rush, and Adam was not exempt from gold fever. In this story the “Black Forest” is mentioned. We found that it was an area near Mt Macedon, and part of a common route to the gold fields.

He had only one experience at mining and that when the Bendigo rush broke out. He with about a party of 20 shouldered their swags and tramped to Bendigo. In crossing through the Black Forest, as it was then called, they met with Black Douglas—a famous bushranger of he time. The party had just camped for the night when Douglas and men—numbering six—came on them. The party were all armed with guns and warned the rangers not to come any closer or they would fire. The robbers only had revolvers so thought it best to do as they were told. They, however, tried a couple of times during the night, but the miners were always ready for them and at last Douglas came to the conclusion it was no use trying again. The bushrangers would have had a fair haul if they had succeeded as each man was carrying a tidy sum of money at the time. Rye didn't do any good there although as he says it was a poor man's diggings all right, as gold was found on many occasions only a few feet from the surface. Everyone who could possibly follow the rushes went, and labourers of all kinds were very hard to get. In some instances if you went to an hotel for a meal you would be told that you'd have to cook it yourself if you wanted it, the cook having caught the gold fever and gone off. Farmers were in sore straits for men at harvest time and wages went up in a very short time from 10s to £4 a week. Finding the diggings no good to him Rye made his way to Colac, where farm labourers were badly wanted, and earned as much as £1 a day trussing hay.

We have ascertained that this move to Colac happened abut 1873, long after Martha had married Joachim Dau. Adam worked for a time as a farm hand and also a road builder.

At the time of this article, Adam was in his nineties. Elizabeth had died many years earlier. At that time he was living in Benalla with another of his daughters.

The old man dearly loves a game of euchre, and takes a very keen and intelligent interest in the game. In the summer months it was not uncommon sight to see him sitting out under the trees reading his Bible and prayer-book.

He died on his 102 birthday. Interestingly Alice and Marge tell the story of his death, but they remembered it as being about Joachim, Adam’s son in law and our great great grandfather. Joachim died in his eighties.

Alice says “and he died on his one hundred and second birthday, sitting up in bed and singing a hymn.” That definitely fits the facts and the personality of Adam Rye.

He is buried in the Benalla cemetery.

Adam and Elizabeth (both seated) with family members:

These early pioneers were the parents of the “unknown” girl in the market, “dragged away” to the farm in Wandong by the older German man. Marge and Alice knew nothing of their colourful lives.

Nor did they know anything about their great grandfather. “there was “some evidence of a high class family, ….. the Von Dows of Bavaria.”

In fact Johann Joachim Ties Dau was born in 1832 in Bukowko, (Neu Buckow in German) in present day Poland. His parents were Gottlieb and Anna. Their town, which they would have called Bukówko, was part of Pomerania, in present day Poland. Situated in what is known as the “Polish Corridor”, over the centuries Bukowko has also been part of Sweden, The Holy Roman Empire, Denmark, Prussia,, France (Napoleon) and East Germany.

Johann arrived in Australia during the 1850s with his wife, Maria (born Maria Winter), who was from the same town and six years younger. The couple acquired a farm at Wandong, near Kilmore.

In 1861 a child, Eliza, Louisa Dau was born. Maria died in childbirth. The baby lasted only a year before it too died.

So in 1865, the thirty-three year old Johann had suffered his wife’s death four years earlier, and his baby daughter, three years ealier.

……….

Now you have the facts and the family tale. We have the knowledge that our roots go back to the very early days of the Colony of Victoria and that the lives of these early settlers were touched by many of the events we read about in history books, including the Gold Rush, bushrangers and encounters with ‘the blacks’.

The immigrants, Martha's parents and husband came from England and Poland as young people looking for a new life.

Martha herself, an older child in a family of twelve children would have helped her mother both with daily tasks and the younger children. She was also according to the tale helping her father sell the produce from their small plot: not an easy life for a fifteen year old girl but probably not uncommon.

Was the older man (actually in his prime at only 33) at the market a good proposition? Was it the Victoria Market or one of the many local markets in the colony? After all Broadmeadows was the country then. Johann had lost his wife and child soon after they arrived in the colony and he owned a farm at Wandong, probably bigger than her father’s small rented plot in Broadmeadows. Did she take a chance, strike out on her own and opt for a better life?

We will never know but she and Johann produced 18 children many of whom also went on to lead colourful lives.

Poor little thing ????

Our Little Allie 1895-1906

Late July 2007, on a clear winters day in Chiltern, a small Northern Victorian town I found myself standing by my great aunt’s graveside. Alice Martha Coates died on the 8th of October 1906, aged eleven and a half.

Thomas and Tessa had just been married at Nagambie and we were heading up the Hume Highway for a little R & R with Anne and Ben in the vineyards of Rutherglen. As we approached the turn off to Chiltern, 38k past Wangaratta where my grandfather Alfred had lived as a boy, we decided to have an ‘explore’. We turned towards Chiltern and found ourselves in the historic main street, complete with restored shopfronts, antique shops and the Historical Society, open for business.

Margaret and I, aware that our mother had been named after her, had grown up hearing our grandfather talk in hallowed tones of ‘our little Allie’ who, in our childhood memories, was almost saint like. You must remember that Margaret and I had grown up on a diet of novels such as Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, one of our favourites. In this novel Beth March, a child almost too good to be true and therefore likely not long for this world dies a lingering but saintly death, nursed by her adoring older sister. Fertile imagination conjured up such scenes as we heard the stories of little Allie's death or held the remembrance badge portraying her as a pretty, serious child. Allie died at Chiltern but that was all I knew, so into the Historical Society to find out more.

The building was slightly musty, its walls covered in old photographs and fortunately for us, as is so often the case, it was staffed by an enthusiastic and knowledgable volunteer. Yes, he knew about Reverend Alfred Coates : We think he lived in this house and yes his youngest daughter died here. After rummaging in the filing cabinet we had the location of the grave in the Chiltern Cemetery and we were able to read a newspaper report on the well attended funeral. Alice had obviously been ill for several weeks and it was no doubt a big topic of conversation in the town, especially as she was the daughter of a much loved Pastor. Maybe other children in the town were also ill in those same weeks.

Who was Alice Martha Coates, our great aunt who died aged eleven?

Our grandfather’s parents were Alfred senior, a Methodist parson, and Emma. The church chose his positions and moved the family every three years, in their case throughout country Victoria. They had four children, Florence, Alfred (our grandfather), Alice and Arthur. The photographs below show Allie with her parents and their house in Chiltern.

Allie died from the disease Diphtheria. This was a very common childhood disease of the times. Nowadays we have a vaccine for it, and antibiotics to treat it, but in those days it was one of the most feared childhood diseases.

It was highly contagious, and Emma and Alfred must have been very worried about the other children catching it. At first the symptoms are like those of a cold, but a horrible film, like a spider web, grows on the back of the throat or in the nose, and makes it hard to breathe. Alice must have had a really bad dose, because only one in ten people over five died from Diphtheria.

Armed with directions to the cemetery we politely extracted ourselves before we heard the complete history of Chiltern and stepped outside into the twenty-first century world. The cemetery is located outside the now small town, in slightly undulating country. It was chilly that day but this small country cemetery would have seen many blistering hot summer days. My thoughts turned to my grandfather: Allie’s older brother Alf, standing with his family at the graveside during the funeral. Some memories were no doubt already etched in his memory and others were forming These would combine to become the story of this tragic event passed down to us.

The little remembrance badge of Allie (shown below) lived in a wooden box on Alf’s desk. As children, we drank in the pathos of her beauty and goodness, amplified by the Victorian novels we read. The telling and retelling of little Allie’s story first by our grandfather and then our mother and aunt has helped Allie’s story retain its enduring poignancy, lifting it out of the commonplace into the world of idealised tragic heroines.

Allie’s grave is indeed in the Chiltern Cemetery, still intact. The modest headstone is there surrounded by the typical wrought iron fence of the era. The only flowers are those of the Cape Weed Daisies growing in abundance throughout the cemetery. The inscription is still legible and simply reads: Our Allie October 8th 1906. As I stood there the story suddenly seemed much more real. Allie was no longer the tragic heroine, but a little girl who died an unpleasant death, mourned by her distraught family.

I picked a small bunch of the Cape Weed daisies and placed it front of the headstone.