Fire and Storm

MY COUNTRY By Dorothy MacKellar

‘I love a sunburnt country,

A land of sweeping plains,

Of ragged mountain ranges,

Of droughts and flooding rains.

I love her far horizons,

I love her jewel sea.

Her beauty and her terror,

The wide brown land for me.

Margaret and I learnt this iconic poem during our respective Grade 6 years and many of its lines are still etched in memory. In fact we can still recite much of it with exactly the same intonation and expression. This poem, written in 1904, captures the tenor of our post, Fire and Storm.

Fire, still very much part of our lives, has also been part of our family history.

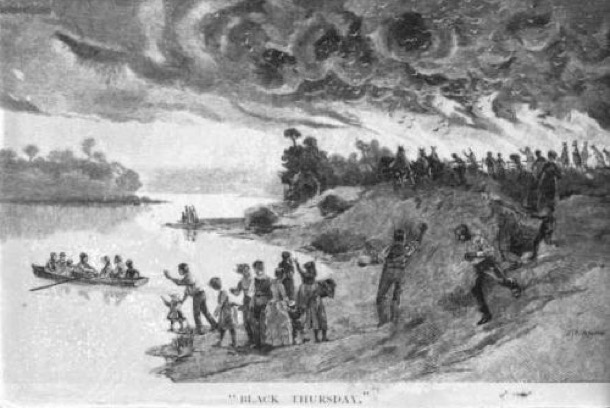

BLACK THURSDAY 1851

The first reference to fire was in1851 with the fire known as ‘Black Thursday’.

Painting by William Strutt

This was the first catastrophic bushfire faced by white settlers in Victoria. The lead up to the fire followed what is now a familiar pattern of events. Reports at the time said that there had been wet years of lush growth followed by severe drought, leaving the bush and long grass tinder dry. Thursday the 6th of February dawned hot and windy, and the fires took off, leaving one quarter of the state black and smouldering. Our antecedents, the Bourke’s of Pakenham, were caught up in the fires in a dramatic way. Shortly before Black Thursday the Bourke’s had taken possession of Bourke’s Hotel in Pakenham. Michael Bourke remained at their selection, while Mrs Bourke was to run the hotel and Post Office.

‘On Black Thursday the whole district was ablaze. Mr Bourke was trying hard to save the station property. Water having been exhausted, milk was brought into play and ultimately the run was saved. Word was brought to him that the hotel property at Pakenham was surrounded by fire. Galloping down there, he found his wife and her children had saved themselves by crouching in the water in the bed of the creek.’

We took this photo of the exact spot, during our visit to Pakenham.

BACCHUS MARSH FIRE 1928

From an article in ‘The Argus' Thurs 12th July 1928

"FIRE AT BACCHUS MARSH.THREE SHOPS DESTROYED"

This was a report on the fire suffered by our grand parents, Alf and Alfreda, in which they lost almost everything, but escaped with their lives. We heard dramatic stories of this fire in childhood and is told below by Marge and Alice on the tape they made in 1990.

The hardware shop was their business, and they had gone out on their own, in an already a difficult time of their lives. Aunty Bert was staying with them to help out, as was her role in the family, as the unmarried sister. Auntie Bert, Alf and Alfreda would have been in their early thirties,Alice was five and Marge three years older. Thank goodness Bert was there as she seems to have had a cool head and took action to get everyone out as the fire took hold.

Marge and Alice’s recollection is fairly accurate, as the newspaper report comments on the strong North wind and the poor water pressure that hampered the fire fighting.

The Argus reports that at one stage,

…. the premises of Mr. G. H. Anderson were threatened , but this danger passed, with a change in the direction of the wind, A good portion of the stocks of Messrs. McLaren and Coates was saved, but considerable damage was done to Mr. Phillip’s stock. It is understood that all buildings and stock, except that of Mr. McLaren, were insured.

At half-past 7 o'clock, in the morning the fire was under control, and all that was left of three of the shops were the walls.’

Mr McLaren may have been uninsured but Alf was definitely not, as he had been unable to pay the insurance. They lost nearly everything.

We had wondered about Alice’s comment about Auntie Bert’s friend Nell Pearce, whose family took them all in after the fire, and yes it was a large and impressive brick house, still standing today:

As Alice states the Pearces were an influential family in the town. They had been an early pioneering family in the area. They built and established the General Store that presumably was very profitable, supplying the miners on the way to the Goldfields as well as the local community. The family then went into farming and other small businesses, and were influential in civic affairs.

Auntie Bert maintained a lifelong friendship with Nell, and neither of them married. I remember Nell Pearce being a name mentioned in conversation and I have a vague recollection of her as an imposing figure. I also remember her at Auntie Bert’ s sewing rooms in Camberwell. She was probably there for a fitting. Little did we know the history behind that friendship.

After cleaning up and sorting our their affairs Alf and Alfreda, the girls and presumably Auntie Bert left Bacchus Marsh and stayed with Grandpa and Grandma Holm in Surrey Hills. Alf then got a job in Croydon as manager of the hardware shop, where they spent many happy years.

BLACK FRIDAY 1939

After the 1851 fires, bush fires occurred in many parts of the State with predictable monotony. The next major statewide fire was in 1939, once again after a prolonged drought. High temperatures and strong northerly winds fanned separate fires that eventually combined and created a massive fire front that swept mainly over the mountain country in the northeast of Victoria, and along the coast in the southwest.

Lilydale Brigade 1939.

Source - CFA Website

More than two million hectares were burnt in the 1939 fires.They lasted for a week. Many, unable to be controlled, were left to burn out.

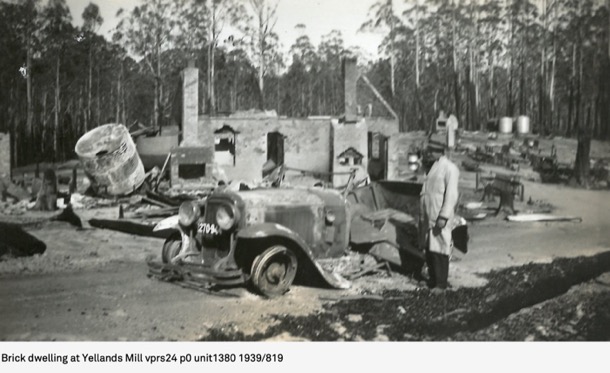

Yellands Mill, where 15 men died:

The extensive damage to over two million hectares of farmland and forest, not to mention the loss of livestock and lives, prompted a Royal Commission. They were tasked with examining the causes of the fire and making recommendations for future management.

The Royal Commission’s specific recommendation was that the various Bush Brigades, and Country Fire Brigades be amalgamated to form a single organisation to fight fire on private land outside the Metropolitan Area. The Forest Commission was responsible for fire on public land and the Metropolitan Fire Brigade was responsible for fire in the Metropolitan Area. Instead of a myriad of uncoordinated small brigades these three organisations were responsible for fighting fires in Victoria.

EARLY BUSHFIRE EXPERIENCE - MARGARET

My first memory of wildfire is of a fire on the empty block next door. The vegetation was sparse: weeds and gorse, with patches of bare clay.

We think it was around 1955. Sue doesn’t remember it, and was probably at school. But I have a clear memory and so I was probably at least four. The image in my mind is of mum, armed with a hessian bag, beating flames. Hessian is a coarse, rough brown fabric made from jute, widely used for packaging. We had a supply of hessian bags, saved from buying bulk chook food. Mum was not a “bush woman” in the Henry Lawson image, but she would have seen this form of fire fighting, and she apparently felt able to take it on.

Fire fighting with a hessian bag.

I don’t remember bush fires being a big part of my life as a child, until I was eleven, in 1962. That year was a big bushfire year in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs: 32 people died and 450 houses were lost. Areas affected included Mitcham, less than ten kilometres away from our place. We were never in danger in suburban Box Hill South, but there would have been a red glow in the sky, and the vivid memory I have of burning gum leaves falling in the back yard, is probably from this fire.

In 1979, I moved to the Dandenong Ranges, where the CFA had much more of a presence, and bushfire awareness was part of everyday life over Summer.

In those first few years, there was still on old dugout just over the road in the forest. It had a wooden sign “Dugout” and what looked like a large wombat hole. A closer look revealed a heavy grey army blanket hanging over the entrance. During a fire, this would be kept wet. Inside was a rounded cave, with earthen floor, ceiling and walls. It would have held a maximum of six adults. There was a metal bucket and a pile of musty grey wooden blankets. I guess it might keep you safe while a canopy fire raced overhead, but I wouldn’t want to rely on it.

The CFA were, and still are, omnipresent. On weekends they collect donations at major intersections. On Good Friday, and in the week before Christmas, they drive through the streets, playing piped music and rattling collection tins. Their sirens regularly echo through the Hills. We can hear the Belgrave, Upwey and Kallista sirens from our place, and sometimes all three will go off. In the past, the siren was used to call in the volunteers, and on a set night of the week, on CFA practice night, they would test the siren at a set time. We like that the sirens are still used, not so much as a specific warning, but as part of our aural landscape.

Nowadays, when we hear a siren, we go straight to the Victorian Emergency app, to check what has happened. Often it’s a house fire, a car accident, a small bush fire. During the Summer months we are more attuned to the sound. Our practice has long been to evacuate on days of dangerous fire weather.

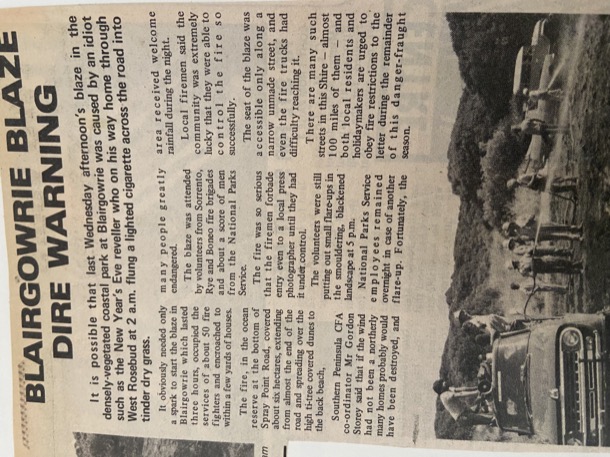

BLAIRGOWRIE FIRE 1980 - SUE

My only experience of fire first hand, was in 1980 at Janey’s house at Blairgowrie. We had all just sat down to lunch. Anna was nearly three and I was pregnant with Thomas. Everything was tinder dry, as it was January and we were in the middle of the 1979-1983 Eastern Australian Drought.

Halfway through lunch there were loud knocks at the door, and a panicking young man asked us for a hose, as he has seen a small fire beginning to build on the Spray Point Road, just fifty metres from the house. Jono and Janey raced down to investigate, but realised that they had not a chance of stopping the fire. It was spreading quickly, fanned by a strong north wind. This was a stroke of luck as this meant it was spreading away from us and towards the beach. We called the CFA who responded promptly, parking several fire trucks at the hydrant on the nature strip.

We were told to block the downpipes with oranges, fill the gutters with water, and shelter inside. The fire was brought under control fairly quickly but not before six hectares of the National Park was burnt.

It would have been a different story if the wind had changed and pushed the fire towards Janey’s house and of course all the other houses.

Local newspapers at the time reported on the fire and issued warnings and advice to residents and holiday makers for the rest of the holiday season that was only just beginning.

ASH WEDNESDAY

SUE

On Ash Wednesday I was at home with Thomas, as Anna had just started school. Thomas was happily playing with water in the shade of our pergola, as it was a very hot day. A nasty north wind intensified as the day wore on and many fires started across Victoria. I was listening to the ABC afternoon show hosted by Tony Delroy, who, as fires broke out, was reporting the outbreaks in real time. He also took many calls from people desperate for information. There were no centralised communications hub, warning system, or, of course, mobile phones. As the fires continued to burn during the evening and that night, the radio was the only source of state wide information. The 3LO radio hosts worked on a roster system to get the information out.

Since its inception the ABC had been responsible for emergency broadcasting, but only on the news bulletins.. In 1997 Ian Mannix was appointed as Program Director for Local Radio Victoria. He changed the nature of emergency broadcasting during the 1997 bush fire in the Dandenong Ranges. The fires burnt for days, three people died and forty homes were destroyed. Mannix asked the CFA for advice on what to say to to listeners ‘who were confronted with flames.’…Interestingly, the CFA had no experience of giving warnings and had never written a warning for people at risk.

Mannix went ahead and took the lead in creating the ABC’s approach to emergency broadcasting. He developed guidelines that included warnings at set intervals, including bush fire alerts for low level fires and urgent threat warnings for more serious fires. The system used in Victoria was expanded nationally after Black Saturday in 2009. Further recommendations were made by the Black Saturday Royal Commission that future refined and expanded the warning systems to television and commercial radio.

From this pioneering work by Ian Mannix, we now have an Australia wide warning system, and broadcasting training and guidelines in each state.

Ian Mannix oversaw the development and implementation of these systems and deservedly received the Australian Public Service Medal in 2012.

MARGARET

The first actual fire we had to deal with in Belgrave was the 1983 Ash Wednesday.

The name “Ash Wednesday” is nothing to do with ash from bushfires. It’s a historical/religious reference. It happens every year, and it marks the beginning of Lent, leading up to Easter, in lots of Christian denominations. It follows Shrove Tuesday, Mardi Gras … the last day of feasting before the deprivations of Lent. The ‘ash’ is sprinkled onto heads or swiped across foreheads as part of the Ash Wednesday service.

1982 had had a very droughty Winter, Spring and Summer. The little creek that runs through the forest over the road had almost stopped, and underfoot the leaves crackled.

The 1983 Melbourne dust storm, when 50,000 tonnes of Mallee topsoil turned the sky dark brown across the city, happened in early February. For me, it hit as I was crossing Burwood Highway on my way to the Ferntree Gully hotel, for an after school cool drink. The dust cloud was over 300 metres high and 500 kilometres long, and darkened the sky for an hour. It’s one of those iconic events where everyone can tell you where they were when it hit.

Image credit: Katsuhiro Abe/BOM

There were many fires that Summer. The CFA across Victoria attended nearly 3,200 fires. Wednesday February 16th was particularly hot and windy.

That morning I had woken feeling nauseous and weak. I rang in sick, and went back to bed. Within a few weeks, I would find out that this had been the beginning of morning sickness. Michael was born that October.

Later in the day I had a phone call from a friend who lived locally, suggesting I might consider leaving, as he had heard there was a fire in Belgrave Heights. Outside was stifling. My neighbour was packing her car but she was expecting to wait and see. I don’t remember having any sense of danger, though, later, we learnt that it was only the late afternoon wind change that stopped the fire from sweeping through Belgrave township and on to our place.

Photo: Tonia Van der Dungen. Christmas Hills CFA

Wind changes during bush fires dramatically widen the fire front, and this one swept through Belgrave South and on to Cockatoo and Upper Beaconsfield.

I don’t remember this, but apparently Ian and Lois were visiting me that day. Lois was pregnant with Sam who was born that winter. Ian speaks of driving home in the afternoon, and taking the sudden decision to drive straight on through Belgrave, rather than the more logical route through to Belgrave South. This would have been exactly the time of day when the fire swept through across the road they would have been on.

Later there were many stories, horrifying and heroic. In Cockatoo, 300 people sheltered during the night in the kindergarten, as a handful of local men kept the flames and embers at bay, saving many lives.

Across Victoria, 75 people died, more than 200,00 hectares were burnt and 2000 homes and buildings were damaged.

Friends from the suburbs rang to check that I was ok. Our little patch of the Dandenongs was untouched, but one didn’t have to drive very far to see the black horror.

Photo: Critchley Parker Junior Reserve. Upper Beaconsfield CFA

Ten years later, I began teaching at Monbulk College, and some of our students were still affected by their experiences in 1983. My friend and colleague Sarah had her Year 8 English class make a booklet marking the ten year anniversary. Everyone had stories, which the students typed up and put together. It remains an important part of the history of Dandenong Ranges, and other affected parts of Victoria.

The tragic Ash Wednesday fires were like those of 1939 Black Friday in intensity, if not in range. They confronted the modern firefighting community with the limits of its capacity and technology. Among the 75 dead, 17 firefighters died that day, some of them next to their well equipped tankers on a forest road in Upper Beaconsfield, when the wind changed and the firestorm swept over them. Changes in firefighting strategies and philosophies were inevitable. The community needed to be better informed and more involved. This is certainly my experience. I was so naive and ignorant, compared to what we expect from Hills people nowadays! There was a huge Royal Commission.

It seemed, as the Commission heard people’s Ash Wednesday stories, that the most dangerous situations people faced were from hurried departures. People died in their cars, not their homes. But the CFA could not guarantee to be there during huge bush fires, protecting every home.

And then there were stories of people actively defending their homes from ember attacks, and saving them. “People save houses. Houses save people.” was the mantra.

The “stay or go” policy began to be developed. As the professionalisation of firefighting, and the ‘Science’ of fire behaviour developed, ordinary people’s anecdotes were often disregarded as over hyped and hysterical.

There was a huge campaign to teach the population about how to prepare their homes, and defend them. Because it was so centralised, the people who lived on the edges of grasslands and those, like us, in what nowadays we call the “flame zone”, were given the same advice. The “go” part of “stay or go” felt like an afterthought for people who were not able bodied. I remember some of our neighbours’ plans were that the men and older boys would “stay” and the women and little children would “go”.

In 1987 the very first General Achievement Test had as one of its tasks information about how to prepare a home for bushfire. It was clearly in the zeitgeist.

My personal experience of this policy is encapsulated by a CFA Fireguard group meeting, in the years leading up to 2010, that we attended on our neighbour’s verandah. The CFA man explained patiently about how bushfires behave, and how we should be preparing our houses, so that we could defend them. The expectation was clearly that we and our neighbours would stay, in the case of a bushfire, and, with mops and buckets of water, we would put out any embers that threatened out house. We pointed to the towering ash forest, metres from our house, and told him we didn’t think our house would be defendable. He was not impressed.

Throughout the Millennial drought, from 1997 to 2009, during the most severe summers, we kept a trailer full of things at Chris’s parents’ place, and had a very clear plan. We evacuated quite a number of times, staying in their spare room. The plan was to insure fully, and simply not to be there during dangerous times. The local schools built fire refuges, and the CFA kept on with its “stay and defend” message. Water saving advice was everywhere. Like many others, we set up a grey water system to water our garden.

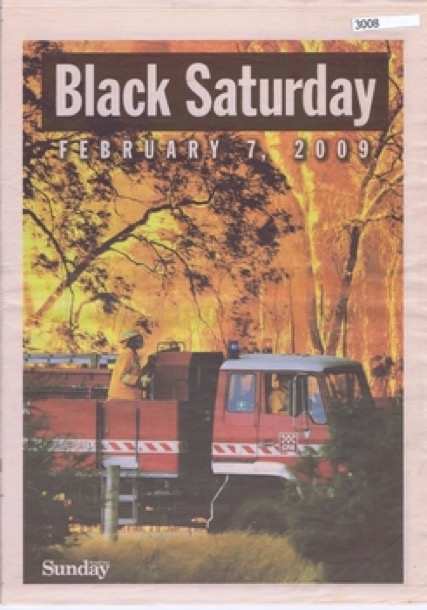

BLACK SATURDAY - MARGARET

And then came the summer of 2008-9. It had been particularly dry and hot. This was the summer when tree fern fronds were scorched, lawns died and record high temperatures were broken day after day. The forecast for the first week of February looked horrendous in advance, with temperatures of 48 degrees forecast, and Chris and I decided to take ourselves camping by the Thurra river, and wait it out. I was glad to be retired by then!

We followed the news of Black Saturday, on the radio, and, once the cool change hit, we packed up and drove out along the Thurra Road, as news of the death toll mounted. Along the Princes Highway, we saw fire fighters’ camp sites with row after row of little tents. The air was smokey, and through the Latrobe Valley we drove through a blackened landscape. At home, the garden was scorched and everything still crackled underfoot.

Back with television coverage, we watched interviews with people who had miraculously survived, saw footage of people’s fire refuges that had been easily breached, and heard the stories of person after person, traumatised by their unsuccessful attempts to defend their homes. 173 people had died, 120 of them in the Kinglake area. More than 450 hectares had burned and 3500 buildings, 200 of them houses, had been destroyed.

Herald-Sun

That cool change was not the end of the 2009 fire season. We evacuated a number of times that February. One day, a fire bug lit a fire just up the hill from us. I was sitting outside, and heard the crackle as flames licked up a nearby gum tree. Chris was walking in the forest. As I drove down to the Belgrave carpark, he was walking quickly back down through the forest, having seen the smoke. When he met a wall of flames, he backtracked hastily, headed toward the road, and hitched a ride with a stranger to near home. The wind was blowing the danger away from our place. I have been mocked mercilessly for my paper post it note on the door telling him I’d gone to the Belgrave car park, but at least he knew that I was out of danger.

In the car park, a gaggle of us watched the Elvis fire bombing helicopters head up the hill, and cheered, and very soon the whole drama was over.

2009 marked the end of the Millennial drought years. Summers since then have been cooler and wetter. But the legacy has been an obsession with rainfall figures, forecasts and climate outlooks.

Our local community facebook page has a member who is a forecaster with the Bureau of Meteorology, who posts every time there is a weather anomaly. It is clear from the responses to him, that we are not alone in our anxiety about rainfall.

THE BIG STORM - MARGARET

It was winter, 2021. There had been yet another Covid lockdown, this one lasting two weeks, finishing on June 10th. Life quickly went back to normal for most people in Melbourne.

But for us in the Dandenongs, the evening of June 9th, and the next morning, brought a massive windstorm which brought down huge swathes of trees, many across roads and onto 112 houses. The wind came at 120kph, but it came from an unusual direction, and our shallow rooted mountain trees were largely untested from that direction. They fell, roots and all, in their hundreds.

Even though the power went off immediately, and all the mobile towers were out, there were 9,500 calls for help logged by the SES. People were trapped in their houses, and many streets, including Michael and Katherine’s were blocked off. There was no way of communicating, in or out, for many days.

My most vivid memory of the storm comes from early on the morning of the tenth. Chris was standing with a view to the north of the forest out the window. His eyes widened, and yet another a great crash came from the forest. He had watched a two hundred foot tall mountain ash eucalypt gracefully fall sideways, taking down another tree of similar size, which in turn took out another one. Like enormous dominos, the three of them had joined the huge pile of previous victims on the forest floor. Later on we stood on the road, looking down where they had fallen and counted thirteen giant trees lying in a messy tangle.

Elsewhere in the Hills, this carnage had been repeated in town after town. We lucky ones who still had homes, watched with dismay as the power company’s estimates of power restoration stretched out beyond a week. Eventually we were able to drive out. It was a weird feeling to drive down onto the flat and find life going on as normal. For us the feeling was very much as if we were still in lockdown. On the Monday evening, I went to choir rehearsal in Ferntree Gully, blinking in the unaccustomed bright lights. Many of us Hills residents had brought items to be recharged during the evening. At end of the night we drove back up into the darkened Hills.

At home, we went into camping mode. There was no hot water, but we had plenty of fire wood, and our very effective wood heater. We cooked with gas and our little portable gas fridge kept our essentials cold. I took to having my bucket bath in the afternoon, when it wasn’t quite so cold in the bathroom. It was ten days before our power came back on, on June 20th.

The reprieve from lockdown lasted only a month. By July 16, Melbourne was back into working from home, home schooling, and leaving home only for essential purposes.

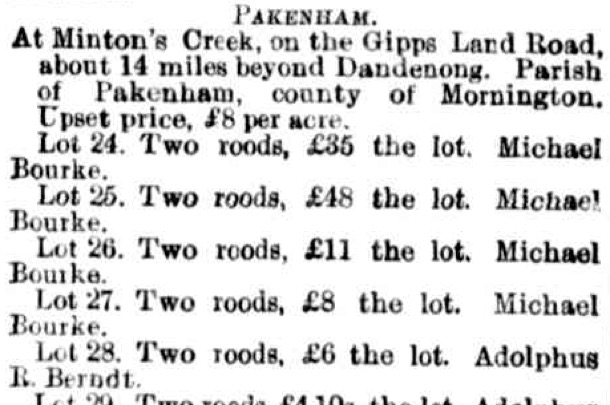

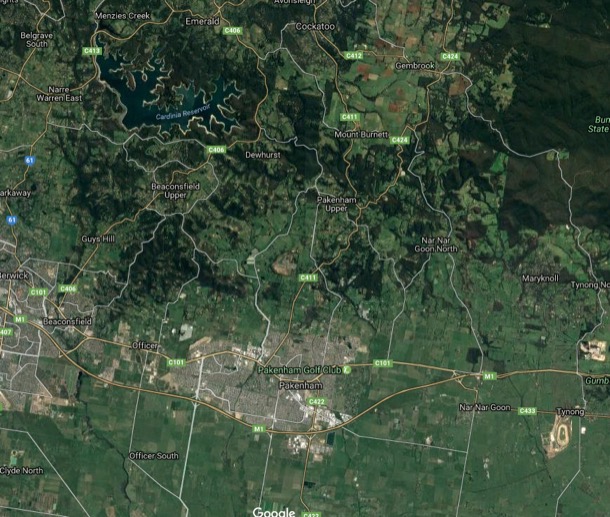

The Pakenham Bourkes 1939 - 2017 Part Two

This example and a number of others are parcels of land around Pakenham.

Much of this investment was aimed at establishing their sons on large local properties.

Michael became an important citizen in the very early days of the Pakenham area. He was an inaugural member of the Berwick District Roads Board. Later this Board became the Berwick local council. Three of his sons were to spend time as Berwick Shire councillors, each of them spending time as Shire President. Michael was also post master and a trustee for the church, the school and the local cemetery. There is also record of nine nephews and nieces coming to Australia from Ireland, each receiving the best he could afford.

Michael died in 1977. Catherine took over the business and became quite a force in the district in her own right.

She lived into her nineties, dying in 1910. Her obituary describes her colourful life:

South Bourke and Mornington Journal Wednesday February 2, 1910

It is quite true to say that never in the history of this part of Victoria has the death of anyone been the general subject of so much interest and discussion as that of the late Mrs. Bourke who, with her husband, was one of the first settlers in Pakenham. The deceased lady was married in Ireland to Mr. Michael Bourke in the year 1838, being then 20 years old. Evidently the plans for their future had been prearranged, for the same day they shipped and sailed for Australia, arriving in Melbourne on St. Patrick's Day, 1839. They obtained employment as soon as they landed, managing a dairy farm at Moonee Ponds, where they remained until 1844, when, having saved money,they took up a run under a squatter’s licence on the Toomuc Creek, opposite Grant's orchard, then known as Bourke and Neville's station. There they remained for a number of years, until shortly before Black Thursday Mrs Bourke and her family took possession Bourke's Hotel, at that time known as the "Latrobe Inn," the husband remaining for a time at their station. On Black Thursday the whole district was in a blaze, and whilst Mr Bourke was trying hard to save the station property (water having been exhausted milk was brought into play and ultimately the run saved) word was brought to him that the hotel property at Pakenham was surrounded by fire. Galloping down there he found his wife and her children had saved themselves by crouching in the water in the bed of the creek. This is only one of many thrilling incidents in their lives.From the time they first arrived in this district to the time of Mr Bourke’s death in 1877, as they made money, they at once invested in land. Banks were unknown this side of Melbourne in those days, and their investments invariably turning out profitable, they slowly but surely acquired wealth. The name of Bourke and Bourke's Hotel will be, for generations to come, remembered as the pioneers and landmark of this part of Gippsland. The lives of Mr and Mrs Bourke have clearly proved what thrift, hard work and stout hearts can do in the settlement of this country, for at the time they arrived, the country was full of blacks camps along the banks of Toomuc Creek, and the country dense bush mostly. Yet out of all this Mr Bourke. made a fortune, buying up land as far away as Dandenong, and settling his sons on the land.

After his death Mrs Bourke continued to carry on and work hard, when there was no call for it, on the hotel property, and, as she repeatedly told the writer of this, she had more than her reward in the welfare and prosperity of her family, and she was proud of them, and well she might be, for her three surviving sons, Thomas, Daniel and David, have all been presidents of the Berwick Shire council, and all hold His Majesty's commission as Justices of the Peace, whilst the daughters are comfortably settled and highly respected. One of one of them, Miss Cissy Bourke has been (and still holds the position) of post mistress at Pakenham since a post office was first created.

With daughters like these, and sons holding the high positions they do, ever ready to give of their time and money in advancing the interest of the township and district, Mrs Bourke. has gone to her rest feeling fully rewarded for the years of her life devoted to and spent for their good. It would be difficult to find in the history of Australia, a parallel case of a man and a woman rising from the humblest rank of worker leaving behind them such a fortune and family so respected.

Mrs Bourke was probably the oldest colonist living at time of her death, having attained the ripe age of 91 years, being a colonist for 71 years and having resided at Pakenham for the last 67 years. She is said to have never, had a day's serious illness, and death was hastened by the severe heat three weeks ago.

Mrs. Bourke who died, on the 24th January at 9 in the morning, was-interred in the Pakenham cemetery on the 26th. A solemn Requiem High Mass was held in St. Patrick's Church from 10 to 12 a.m., the coffin being heavily draped in mourning, thronged with relatives and friends of the deceased. At the close of the Mass, the coffin was carried to the hearse and proceeded to the cemetery, a procession of carriages and horsemen fully half a mile in length and composed of people of all creeds following, and so was laid in her last resting place with sorrow and with respect: a good mother, a kind hearted woman, and a true colonist.

Michael and Catherine had fifteen children in total. Here in birth order is what we know of each of them:

James, born 1839, at Moonee Ponds. He was married twice: first to Johanna Conway in 1867, and secondly to Margaret Cahill in 1877. He had ten children all together, all girls. James’s property was in Dandenong, near the corner of Dandenong Road and the M1 freeway. He died in 1892 and is buried at Pakenham Cemetery.

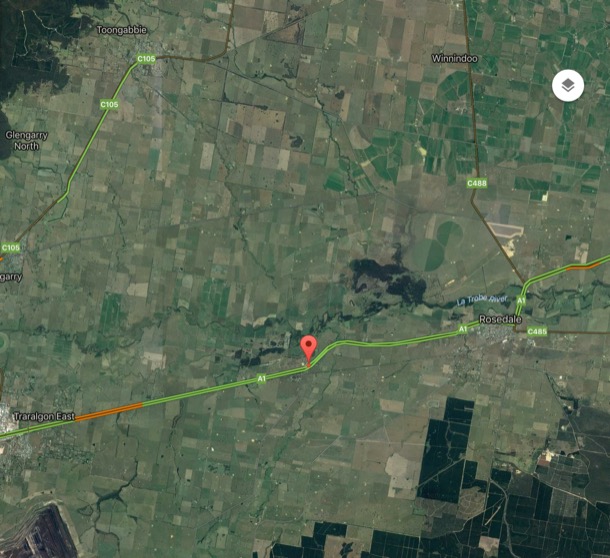

John was also born at Moonee Ponds, in 1840. He married Mary O’Neill in 1877. John and Mary lost their fist two children in infancy, but went on to have another five. The family settled in Leawood Park Rosedale, a long way from Pakenham. Today, Leawood is an Angus stud farm which has been in the same family, the Stuckeys, since 1944. It is a covenanted Trust For Nature property, protecting 18 hectares of important floodplain habitat along the Latrobe River.

John died in 1892, He is not buried in the Rosedale cemetery, but his son John who died aged 4, a year before John senior died, is there. Mary went on to live until 1935.

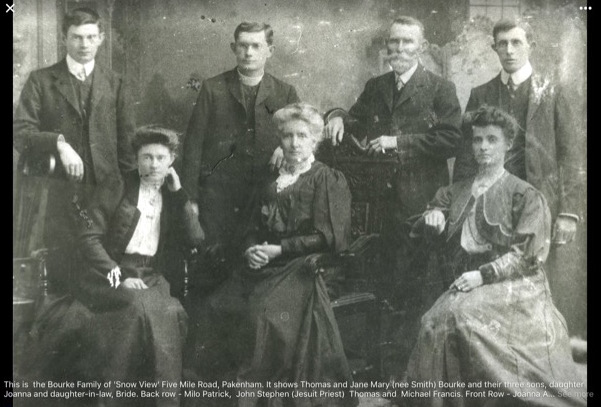

Thomas was Michael and Catherine’s third son, also born at Moonee Ponds, in 1842. In 1875, Thomas married Jane Smith, daughter of another family who came from Shanagolden in Ireland, and settled in the Toomuc Valley. The Smiths probably travelled from Ireland on the same ship as Thomas’ parents.

Thomas and Jane moved to the property “Snowview”, which Thomas had “selected” some time earlier. They had four children. Thomas, like his father, was very prominent in local politics, serving on the Berwick Shire Council for forty-five years. During most of that time he went on horseback from his home at "Snowview" to attend the meetings at Berwick, and it was only through advancing age that he finally resigned from the council. He lived at “Snowview” right up to his death in 1929. It is now a heritage listed property, which remains in family hands to this day.

Thomas and family:

Mary Ann was born a year later, in 1843 the last to be born at Moonee Ponds. Mary died aged six. We know very little about this Mary, we don”t even now where she was buried. The family was living at Minton’s Run when she died, perhaps she was buried near the slab hut they lived in. The Pakenham cemetery wasn’t formally gazetted until 1865, though, reportedly, there were burials there before then. A devastating fire in 1944 burned most of the wooden grave markers in the cemetery anyway, so much of the historical graves are now unmarked.

The fifth child is Michael, born in the slab hut at Minton’s Run in 1844. Unlike the other sons, Michael did not take up life on the land, but became a lawyer. He married Ellen (Nellie) Doogan in 1884. Nellie was the daughter of Pyalong publican, Hugh Doogan. The family lived in Parkville, near the city of Melbourne. Michael and Nellie had six children, the second of whom, Hugh, was our grandfather.

Michael died in !908 and is buried with Nellie and their third son Austin, in the Kew cemetery.

Michael and Nellie's Parkville house:

Michael and Nellie's grave:

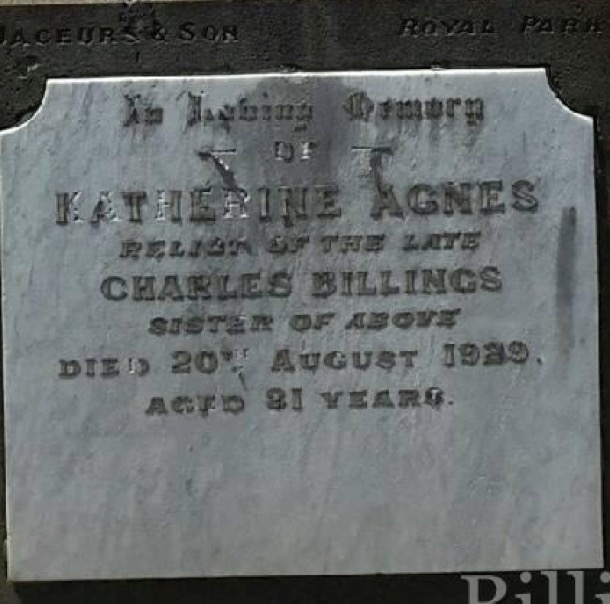

Catherine is the sixth child. She was born in 1845 at Minton’s run. She married Charles Billings in 1878. They lived in Prahran, in a house named “Pakenham”. It seems to have been an important family place, with births marriages and deaths all occurring there. Charles and Catherine had seven children and Catherine died in 1929, and is buried in the St Kilda cemetery with her sister Mary Lucy.

Daniel Bourke, was born in 1847. He was Michael and Catherine’s fifth son, Upon retirement from the Berwick Council, he is quoted as saying, “Our nation was not built on bloodshed, but on hard work”.

Daniel, like almost all of his brothers lived out this ethos on the land. Michael and Catherine seem to have imbued their children with the desire to do well, serve their community and ensure that their own children were also settled well. Daniel followed the family line. He married Fanny Levers who produced eight children and pre-deceased Daniel by only three years.

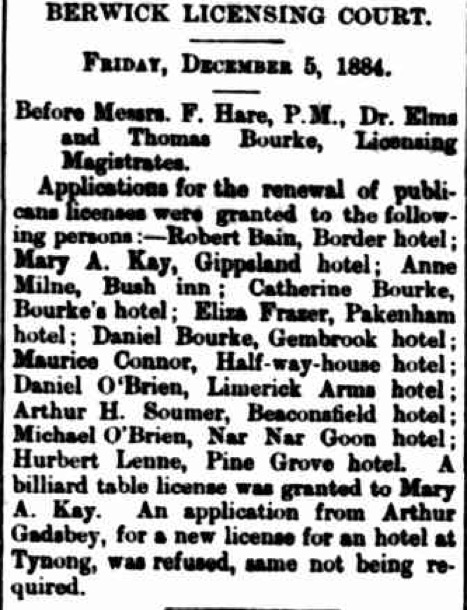

Daniel’s early years were spent in Pakenham where he owned Mt Bourke, some 400 acres, sold off from a larger property owned by the Hentys. This property is now in central suburban Pakenham, as we mentioned in the previous post. The heritage listed house was built one year after Daniel sold the property, probably by the new owners. David also owned the Gembrook Hotel in Pakenham.

What is notable about this article is that it also includes Catherine’s application for Bourke’s hotel, and Daniel’s brother Thomas, is the licensing magistrate!

It is Daniel’s public life in Pakenham that gives us some idea of the man. Daniel served on the Berwick Council for twenty years and it is the speeches from his farewell dinner that offer these insights. Fellow councillors were obviously very sorry to lose his services, as they commented that,

‘…his name will be remembered in Pakenham with pride and honour..’

‘Berwick Shire is losing on of its leaders.’

‘He was one of the largest-hearted men in the district….’

‘His calm, cool, warm-hearted manner won him friends from all ranks. He was in the full sense of the word a reliable man and a gentleman.’

Daniel held many other other positions the community, as President of many clubs, farming organisations, and was also regarded as a pillar of his Church and well regarded by others…’

Daniel’s own speech in reply to all these accolades is also revealing. In reply he says that it was the noblest duty of a man to help his neighbour and the magnificent national feeling that was through gathering particularly pleased him. Australia to him was the greatest country in the world.

This offers an insight into Daniel’s character but also to the ethos that appears to run through the family, and no doubt contributed to their success.

Daniel and his family moved to Stratford where he and David, his younger brother of Monomeith fame, owned another property, ‘llowalong’. Daniel and his and wife felt that there was not enough ‘scope’ for their sons in the district and it was for their sake they were leaving Pakenham. Daniel died at the ripe old age of 88 leaving one of his sons possibly James on the Stratford property.

Mary Lucy was probably the last child to be born at Minton’s Run. There are doubts about the date of her birth. Mary Ann had recently died, and this Mary was perhaps given her name. She died, unmarried and is buried in the St Kilda cemetery. On her grave it says she was aged 37, but this would make her born the same year as her namesake Mary Ann. Had she lied about her age? Is the information about the two Marys wrong, and they are the same person? We don’t have a grave for Mary Ann, so there are unanswered questions about these two. The fact that Catherine was buried in the same grave as Mary Lucy, and near to Prahran, when Catherine lived suggests that the two were close. Perhaps unmarried Mary lived with Catherine and Charles.

Ellen was the first child to be born at Bourke’s hotel right in Pakenham. She was born in 1851, the year of the big fire that burned the Minton’s Run property. She married John Augustus McKeone, of Port Albert Victoria. The couple lived at times in Beechworth and in Narrandera. They had a total of nine children. John died in 1895 and Ellen in 1934.

Milo was born in 1852. He never married. He died aged only 25, “after a short illness” at the home of his older sister Catherine, and is buried in the Pakenham cemetery.

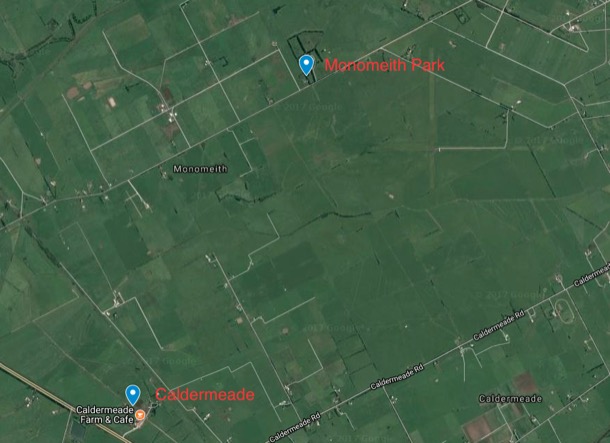

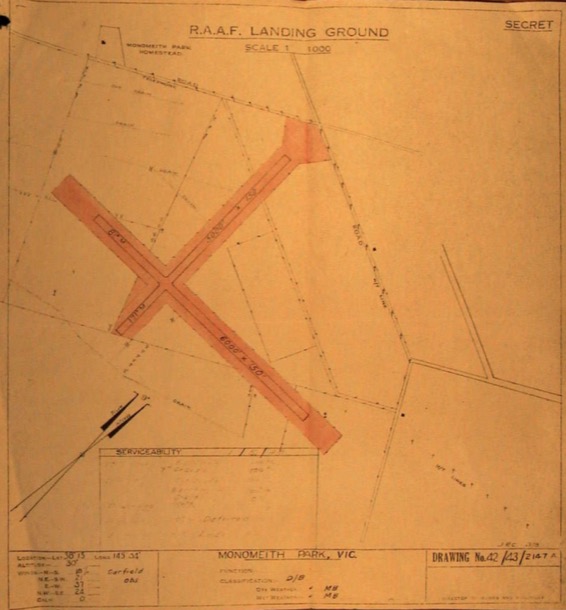

Michael and Catherine’s youngest son David, was born in 1856. He married Mary Hunt in 1888. David had bought Monomeith Station in the mid 1800’s. It was originally 3000 acres comprising what is now the area of Monomeith and Caldermeade.

On the map you can see the World War two airstrip, south east of Monomeith Park. It was constructed as a RAAF fighter base to protect Yallourn where all of Melbourne’s power came from. In the end they only built two gravel strips, in the shape of a cross.

It was fine grazing land on black loam country and is part of the rich history of the early settlement of the area. Over the years hundreds of prime bullocks were driven to Newmarket sale yards in large mobs. According to local legend this feat was undertaken by the well-known character “little” Billy Matthews who reputedly drove the Monomeith mob all the way by himself.

In 1886 1000 acres of Monomeith was sold at auction, probably the swampy section. The carrying capacity of the land retained is referred to in, “Memoirs of a Stockman” by Harry Worthington Peck:

“However, the Bourke brothers [David’s sons, Michael and Hugh] at Old Monomeith Homestead of some 2000 acres have today the pick of the estate carrying some 3000 cattle of mixed ages and all fattening. This is probably a record for the Commonwealth and proves the virtue of top-dressing even on the richest natural pastures”

The Cattle King, Sir Sidney Kidman, visited Monomeith for both business and pleasure, another indication of how well known this property was.

In later years the property was again subdivided presumably between David’s two sons Michael and Hugh. Their descendants retained ownership until recently. Ironically after so many years in family hands, through three generations, we have discovered both the properties in advertisements in the real estate section of the Weekly Times.

Caldermeade was sold in 2016.

Through articles and advertisements for the property, in the local paper, we discovered more family history. For instance, only four years ago, there was an article in the Pakenham Gazette about Brian Bourke, the then owner of Caldermeade.

A fall from a horse, broken bones and 32 hours lying in a paddock would spell disaster for most 77-year- olds, but Hughie Bourke comes from tough stock. Fearing the worst, family and friends rallied together last week to rescue the stricken grandfather after he was reported missing last Thursday. Now recovering in The Alfred hospital with a shattered femur and pelvis, Hughie reckons he spent his marathon ordeal enjoying the company of animals on his Caldermeade property, but was disappointed to miss the day’s horse racing. Falling from his horse, he remained injured on the ground for almost a day and a half, watching the changing sky and surrounded by foxes and cattle. And while “the old cockie” has a long road to recovery ahead, he told his kids that it was a “bloody beaut” watching the clouds go down and sleeping next to the animals on his farm.”

Monomeith is on the market at the time of this post, July 2017, thus ending three generations of Bourkes running cattle on this property. An article published in the Pakenham Gazette describes the property:

‘Monomeith is heritage listed by the Shire of Cardinia because the house, which was built about 1899, and trees represent a long-term farming enterprise carried out by one family.

The old woolshed, and early picket fences and gateways that survive along the frontage and in some of the paddocks are a reminder of times gone by.

The large double-fronted weatherboard verandah farm house has been home to the Bourke family for more than a century.’

Margaret was the twelfth child of Michael and Catherine. We do not know the exact date of her birth but we know she married Robert Massey Coote in 1883. In 1886, in partnership with Lance Herbert the Cootes established a store and transport business in Orbost. They had three children. Robert died in 1891, and Margaret in 1935.

Agnes’ birth date is also unknown, but we know a little about her life. She married George Fraser of Aberdeen, Scotland. The family lived first in Nar Nar Goon and then in Aukland, New Zealand. They had six children, three born in Australia, and three in New Zealand.

Richard is the next child, but he died in infancy

Cecelia (Cissy) was Michael and Catherine’s fifteenth and youngest child. She never married.

The original Pakenham Post Office opened on 1 February 1859, with Michael as the postmaster. Catherine took over when Michael died in 1877, and Cissy took over from her, serving for many years. The history of Pakenham Post Offices is a bit garbled because, once the railway station opened, in 1977, there were two. Post Mistress was an important official role. For instance Cecelia’s name appears in 1909in the official Federal Gazette as the Electoral Registrar for Pakenham.

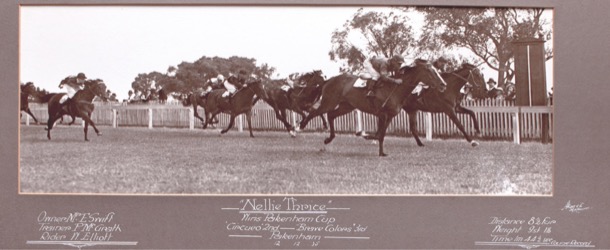

THE BOURKES : A RACING DYNASTY

From the early days at Bourke's hotel, Michael showed an interest in horse racing. We have no idea if this interest arose in the colony, where impromptu race meetings were common, or whether the interest came with him from Ireland. As Ireland has such a long and rich history of horse racing, this is quite likely.

Records show, that Michael and Catherine lent the paddock behind their hotel for the first race day picnics at Pakenham. This area was later named Racecourse Road. With great enthusiasm and involvement from Michael and his sons, racing flourished and in 1875 the Pakenham Racing Club was formed. Michael’s sons continued the family involvement, guiding the development of the club after Michael’s death in 1877.

Our direct descendant Michael, fourth son, left Pakenham for a law career in Melbourne. The rest of the family that remained in Pakenham continued to build a racing legacy.

David Bourke, the youngest son and owner of Monomeith Park, was a particularly good horseman and it is his line that continued the public involvement in racing through to the present day. David helped the Club to prosper in the early days, making his back paddock available for race meetings. This area was later named Racecourse Road, and was the site of the Pakenham Racing Club until 2014.

In the 1900’s the club fell into semi obscurity.and the Bourkes once more became involved in response to:

‘a letter from a local policeman to the Chief Secretary’s Office prompted an official letter being sent to the Pakenham Secretary Mr. A. L. Fairburn, requesting action be taken to rectify the situation.’

Hugh and Michael Bourke, David’s sons, came to the rescue, raising 4,000 pounds to reconstruct the course. The course was seven furlongs, 54ft. (1424m) in circumference.

After David’s death it was his sons Hugh and Michael who played the crucial role of keeping the club alive and it continued to hold picnic race meetings. The land was leased to the club by the Bourkes for no fee on condition that profits were spent on public amenities.Finally despite pressure for the site to become Crown land,the Bourkes agreed to sell the track to the Pakenham Racing Club for 25 000 pounds ($50 000). The deal was finalised in 1957.

"It was about a quarter of what it was worth,but back then our family wanted it to stay a racetrack forever and we always thought it would, " Hughie Bourke is quoted as saying.

The Bourkes maintained their interest in the club after the sale, serving on the committee and fulfilling other roles. Michael, David and Gavan held the position of Secretary between the years 1926 and 1999. A number of other family members also served on the committee for lengthy periods of time.

Early this century as the suburban sprawl reached Pakenham the racing club committee decided to sell the land and use the considerable profits to redevelop a new racing track at Tynong on a site of 246 hectares. In February 2014 the cub hosted the last race meeting at the old site and at the time, Gavan Bourke commented that it was sad that the old track,on a 27 hectare site had been sold for redevelopment to accomodate the urban sprawl.

The Bourke family interest in racing is also evident in positions held within the Victorian Racing Club [VRC] by David’s direct descendants.

David Bourke [1930-2005] David’s grandson, was a racing administrator for 60 years. He began his career after his father’s death when aged 19 he took over as Secretary of the Pakenham Racing Club.

He served on the VRC committee for twenty years, seven years, as Chairman. In this role he presided over the nation's most famous race, the Melbourne Cup from 1991 until 1998. The David Bourke Provincial Plate is run annually in June at Flemington, the Saturday of the Queen's Birthday weekend.

David’s brother John, also had a career in the thoroughbred racing industry. He was employed by the VRC as the Veterinary Steward. During a long and distinguished career he was instrumental in the introduction of drug testing of thoroughbreds. Dr Bourke went on to become a world authority on equine medicine and the use and effect of drugs on horses.

So from the first race meeting in Pakenham, in the early days of the Colony of Victoria, Michael’s and Catherine’s descendants have been involved in the horse racing industry. Some, such as our line, have had a recreational interest in horse racing whereas others, such as David’s line, produced several Bourkes who made their careers in thoroughbred racing. Quite a family affair through the generations!

Pakenham, the visit

So, in May 2017, one hundred and seventy-three years after our great, great, grandparents Catherine and Michael Bourke selected Minton’s Creek Run, we stood on the very spot. In 1844 the area was probably grassy woodland, open country, well grassed and with shade for the cattle. Like in so much of Victoria, the early settlers, our great, great grandparents amongst them, could just take possession and let their stock loose. Today the area is still a pastoral landscape but obviously broken into smaller holdings. Minton’s Run appears to be quite hilly, rising from the creek to the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges in the North, and undulating to hilly country in the East and the West.

It must have been a hard life. The day we were there was cold, and after recent rain the ground was soft and muddy. Not much fun carrying water from the creek in this weather. Presumably Michael and Catherine’s bark hut would have been near this water source but up on the hill a little, safe from floods and away from the soggy creek flats. We walked a little way along the dirt road imagining Michael and Catherine building their bark hut, collecting water from the creek and tending their stock.

Turning south, we drove to Pakenham on the Toomuc Valley Road. It would have been an easy, flat, gallop downhill to the hotel site on the corner of what was, and still is, the point where the Princess Highway crosses the Toomuc Creek.

Not so easy for Michael, the day he galloped this way to rescue his family during the 1851 bushfires. Parking opposite the hotel, we walked the short distance to the creek, quite a substantial one, especially after rain. This is the spot where Catherine and the children sheltered from the flames, and where Michael found them safe and sound.

From this side of the road the heritage-listed original chimney is clearly visible. The hotel is undergoing yet another extension and renovation but the old bricks are just visible at the corner of the chimney where the layers applied over the years are crumbling away. Today the hotel is an ugly pile of add-ons and extensions including prominent Thirsty Camel drive through bottle shop. The chimney lives on, as does the business, obviously still thriving.

What next? As Pakenham Cemetery was nearby, we thought it fitting that we see where our great, great grandparents were buried. The cemetery is on a hill above the highway which was the main road to Gippsland, back when Michael and Catherine offered a stopping place to travellers. Nowadays, though still busy, and still called the Princes Highway, it is bypassed by the Princes Freeway.

We had seen a picture of Michael and Catherine’s grave, and so had seen the shape of the cross on the top, but the picture had not shown where it was, nor had we been able to read the writing.

It’s not a very large cemetery and soon we found an area with various recognisable Bourke names.

We should have known just to walk to the highest spot! There was the patriarch towering above everyone else.

Michael and Catherine's grave:

Here is the original newspaper article about Michael’s death in 1877:

We regret to chronicle the death of Mr. Michael Bourke, the oldest inhabitant, as we understand, of Pakenham, whose remains were laid in the Pakenham Cemetery on Wednesday last. His death was accelerated by an accident, which, although it might have had but little effect on a younger man, hastened his end. A few days before his death he had gone up to the hay-loft of his stable to pull down some hay, and in descending the ladder missed his hold and fell heavily on the side of his head. At first it was not considered that be was much injured, but continued to get worse until be died. Although it rained almost incessantly during Wednesday the funeral was a very .large one, comprising most of the old residents for many miles around, by whom deceased was generally esteemed. About three o'clock the cortege started, the body being conveyed in a splendid hearse, followed by vehicles containing deceased's wife, daughters, and other female relations, his sons following; after whom came a number of vehicles, and, lastly a very long array of horsemen. The funeral service was conducted by Mr. D. J. Ahern, of Dandenong, in an effective manner, although during the ceremony the rain was falling very heavily. - From a first visit to the Pakenham Cemetery we cannot say much in praise; of the residents who permit it to remain in its present state so long. There are only five acres of it, which were granted by Government, and it is not creditable to the, residents to allow it to remain almost in its natural state.

The cemetery was very well kept on the day of our visit, and is clearly still in use today. We saw many names we recognised, such as James, Michael and Catherine’s eldest and his daughter Nellie, who had died, aged 17. We noted that four of Nellie’s uncles carried the coffin, including our great grandfather Michael, by then living in Melbourne.

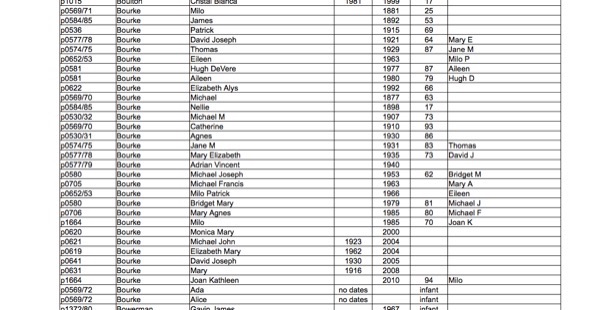

Here is a list of all the Bourkes buried in the Pakenham Cemetery:

Looking down on the sprawling suburban growth that is now modern day Pakenham we could just see where another piece of Bourke history still stands, Bourke House. We drove down and pulled off the busy feeder road to the freeway into what will become the gateway to a new housing estate. It will eventually swallow the last vestiges of the first Pakenham Racing Club track that the Bourkes were instrumental in setting up. Today the track still visible surrounded by mud, trucks and cyclone fencing. Margaret and I approached Bourke House, right next door.

This racecourse residence and stable complex is heritage listed as it is a large, successfully designed and well-preserved residential complex from the 1920s, linked with a private racecourse and associated with notable district figures, such as the Bourkes, prominent Pakenham graziers and horse racing identities. Through its associations with the Bourke family who have played major roles within the Victorian Racing Club, and with the Pakenham Racing Club, this property has been significant in the history of racing in the shire.

The house and stables now sit behind a locked gate next to the sea of mud that was its racetrack. Hopefully when the housing estate is complete the house will also be tidied up and put to use again.

As we sat in the car, map in hand, we realised that, within walking distance of Bourke House, were several significant Bourke properties: the Bourke’s Hotel, the youngest son, David’s first property Homegarth, and the fifth son, Daniel Bourke’s Koo Man Goo Nong which he changed to Mt Bourke.

Homegarth and Mt Bourke have been absorbed into suburban Pakenham. Homegarth no longer exists, but the reminder of its existence is in the name of a playground and Childcare Centre nearby.

Mt Bourke is now a housing estate.

We drove and walked around the housing estate looking for acknowledgement of the history of the area, or directions to the original house. We found none and presumed that the house had been destroyed in the name of progress. But no, on the way home we were enlightened, at, of all places, the ‘Olivers' fast food outlet on the Monash Freeway. Collision of two worlds: as the chatty young lady passed us the coffee and egg sandwiches, she told us that she lived in that very estate, and yes, the house still stands at the top of the hill. Now the house looks down at the closely packed phoney heritage houses and other trappings such as Stockyards Playground, instead of productive fertile creek flats.

Koo Man Choo Nong/Mt Bourke:

A little further out of town we found Snowview, owned by Thomas, Michael and Catherine’s third son. We could just see the ranges through the drizzle, a wonderful view. No wonder Thomas called his property Snowview. Still in family hands, Snowview is now an equestrian property. It stands at the corner of Bourke Road and Five Mile Road, and is bordered by very, very old, gnarled cypresses. Maybe Thomas planted these as a wind break from cold winds from the ranges?

It was getting late but we decided to attempt to find Monomeith, originally owned by David, the youngest son. Monomeith, still on the map, is situated on rich farming land at Nar Nar Goon. The roads were busy with trucks and commuters, very unpleasant driving conditions in the rain, but we soldiered on through several wrong turns, until we decided also to head for home. We now know, after further research, that we were very close. An excuse to go back another day.

The Pakenham Bourkes 1839 - 2017 Part One.

New South Wales had been settled as a convict colony in 1788, when the first fleet arrived. Over the next fifty years, many convicts were transported there, and many English free settlers chose to try their luck in that distant land. By the 1830s, there was clearly a need for more immigrants in the colony. Not only was there three men to every woman, but the balance of convicts to free settlers was all out of whack. There were not enough reliable trustworthy labourers to work on all the properties that had been developed, especially all the sheep stations.

A committee was set up to address this issue. It looked like a win-win situation with England, where the population had outgrown the jobs available, especially in the country. It should have been easy to entice the right kind of working people to settle in New South Wales. But America was also expanding, and was a fifth of the distance. It was hard to persuade people to undertake a perilous sea voyage to New South Wales instead.

A scheme was set up whereby young country women of good character would have their sea passage paid for and be guaranteed a job as a servant in rural New South Wales.

Predictably the people whose task was to head off into the countryside and interview young unmarried women of good character, took shortcuts, and, by the sound of it, simply herded up the “mere sweepings of the streets of London” who were all too happy to take the money.

On one large ship, the David Scott, 226 single females came out to New South Wales. Mr Marshall, Royal Navy, the hapless “superintendent” of the ship said of the 226 “there were not more than twenty-five that I would consider suited for country servants”. Furthermore the David Scott was a very large ship and there were more than fifty men in the crew. They seemed to have been totally out of control ‘they .. had unrestrained intercourse with them during the voyage” (in this context ‘intercourse’ just means anything from unsupervised conversation to what it means today) ‘I do not allude of course to the whole of the women, but to upwards of forty of them, whose abandoned and outrageous conduct kept the ship in a continual state of alarm during the whole passage’

The committee overseeing this scheme were supposed to have “personally questioned every female for the purpose of ascertaining her age, occupation and qualifications in other respects for the colony. Either the powers of dissimulation (lying) possessed by abandoned females of the lowest grade must be very great indeed and must be well backed by forgery, or the gentlemen of the London committee must have been marvellously unskilled in discriminating character.”

After this debacle only small ships were used, and many other checks and balances were put in place, including the selection of potential migrants. It is in this context that, in 1838, Governor Richard Bourke contacted his friend, Thomas Spring -Rice, Baron of Monteagle, and landlord to young Michael Bourke of Foynes Island Shanagolden, County Limerick, Ireland.

Governor Bourke asked Spring-Rice to carefully select suitable people to participate in a scheme to emigrate to New South Wales, and, in particular, the newly colonised area of Port Phillip. In 1839 13 families who had been Spring-Rice’s tenants, including Michael and his new wife Catherine, emigrated to Australia on the Aliquis. Most settled in the Port Phillip area. By 1858, about 800 ‘Monteagle emigrants” had settled in the new colony.

Monteagle county in New South Wales, containing the towns of Forbes and Bathurst, is named after this Irish nobleman.

So Michael and Catherine Bourke, our Irish great great grandparents and founders of the Australian branch of the Bourke family, arrived in Australia on St Patricks Day, March 17th in 1839.

On the ship's list Michael, 24, is listed as an “agriculturalist”, with his unnamed wife aged 22, though perhaps she was only 20. Catherine had in fact been a dairy maid back in Limerick.

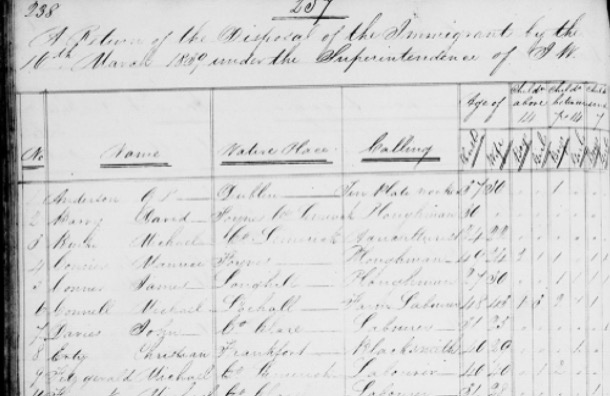

Close up of the Aliquis passenger list. Michael Bourke (misspelt as Burke) third on the list.

In an interview carried out when Catherine was a very old lady she said that they were married in Cork City, just before they left for New South Wales on the ship Aliquis,

And yet, when they arrived at Sydney, on March 2nd 1839, Michael and Catherine lost no time in seeking a priest to bless their marriage, and on Saint Patrick’s day, the ‘Banns of Marriage’ were read for the first time. It was at St Mary’s cathedral in Sydney where, 22 days later, the couple made their Vows of Marriage, on April 8th before Fr Francis Murphy and their friends from their home parish of Shanagolden, who had traveled with them from Ireland.

Work in Sydney was scarce and the ship John Barry took them along with most of their fellow travellers to the newly laid out town of Melbourne. Michael and Catherine spent their early days in Moonee Ponds, managing a dairy farm. The first three sons, James, John and Thomas were born there.

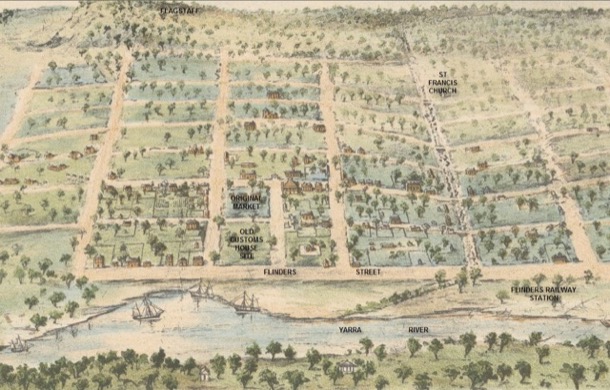

Just four years before Michael and Catherine Bourke arrived in what was then the Colony of N.S.W. Melbourne had begun its ramshackle development. John Batman, entrepreneur and settler, signed a treaty with aboriginal occupants of the Port Philip District, the Kulin nation. He promptly claimed over 500,000 acres north and west of present day Melbourne and also famously declared the present site of Melbourne’s CBD, as the place for a village. The then Governor of the Colony of NSW, Governor Bourke, became concerned at the unruly and illegal occupation of land and took charge, declaring all settlements invalid. He appointed Captain Lonsdale to represent him and run the settlement of Port Philip. Fees for grazing rights to squatters were imposed and Governor Bourke approved Hoddle’s plan for the streets of Melbourne. This is new world which Michael and Catherine entered as they stepped off the boat to begin their new life.

Hand drawn map of very early Melbourne, around 1837

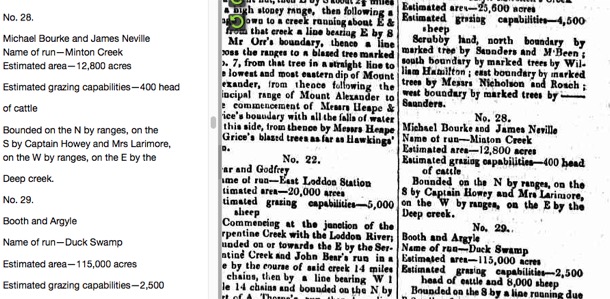

The family moved to near Pakenham in 1844, with their friends the Nevilles, who had come out on the Aliquis with them from Limerick. Under the partnership names of Neville and Bourke, they settled in the Toomuc Valley area, taking up the “Minton’s Creek” run, which extended towards Upper Beaconsfield, 12,800 acres, about 5 square kilometres. Here, our great, great grandfather, Michael, was born in their ‘slab hut’ home in 1844.

Minton's Creek Run covered the whole of present day Pakenham Upper

The Minton's Creek house site was in the centre of this aerial photo

In 1850, the Bourkes bought the Latrobe Inn, a hotel on the main Gippsland Road, where the Toomuc Creek (also known as Bourke’s Creek) crosses the main road. It became known as Bourke’s Hotel. Catherine and the seven children they had by then moved to the hotel to manage it, while Michael stayed at the station.

Bourke's hotel

Only the original chimney stands today.

n February, 1851, after a prolonged drought, a massive bushfire covered a quarter of what is now Victoria. The smoke blew on strong hot winds, wreathing Northern Tasmania in thick smoke. It became known as Black Thursday. The story goes that Michael fought the blaze, first with water, and then milk from the dairy.

Word reached him that the hotel itself was surrounded by fire. He galloped down to Pakenham and there he found that Catherine and the children had hidden in the Toomuc Creek bed and escaped the blaze, and that the hotel itself had not burnt.

from Black Thursday, a painting in the State Library

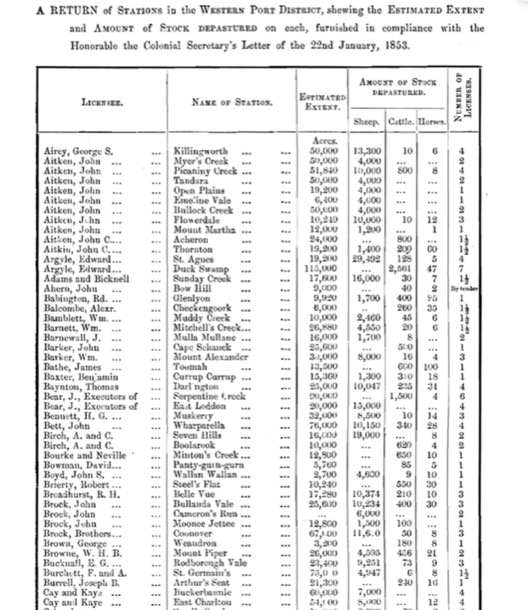

They restocked the property and in an 1853 census it was reported that Bourke and Neville had 650 cattle and ten horses on their 12,800 acres.

Bourke’s Hotel became one of the best known stopping places on the way to Gippsland. Later it became the Princes Highway Hotel and its chimney is still there today.

It was a real hub of the district. It was the polling station and the post office for the area, and Michael Bourke was postmaster at Pakenham for 30 years, and after his death, in 1877, Catherine and unmarried daughter Cecelia continued to run the post office.

In his 1942 book Memoirs of a Stockman, Harry Huntington Peck wrote:

Old Mrs. Bourke who was the landlady of the Pakenham hotel at the bridge over the Toomuc creek for so many years was an institution of the district. She was most popular with the Gippsland travellers and drovers as she took pains to make all visitors comfortable. Her fine sons David and Daniel prospered as graziers and bought good properties, the one Llowalong originally part of Bushy Park on the Avon near Stratford, and the other Old Monomeith, where the next generation Hughie and Michael, trading as Bourke Bros., are today the largest regular suppliers of baby beef to Newmarket, are well known as the owners of show teams of first-class hunters and hacks, and of late years, have been very successful in principal hurdle and steeplechase races.

It was at Bourke’s Hotel that the remainder of the children were born. There were fifteen in all, but two died in infancy.

Gradually the family grew to adulthood, and, when large areas of land were thrown open for “selection”, all the boys in turn gained properties.

Some of them are still in the hands of their descendants.