Shoreham

Books of Our Childhood

18 09 24 13:00 Filed in: Children 1950s

Books have always played a large part in our lives and I cannot remember a time when we have not had a book ‘on the go’. As children we grew up with books in the house. Our parents read at night when we had gone to bed.

We are three years apart, and our early childhood experiences are quite different. Despite the three year gap, when we read lists of books for little children, from those times, the same titles resonate for both of us.

As we became independent readers, home time meant being left much of the time to our own devices. The municipal library was our source of escapism, adventure and vicarious happiness.

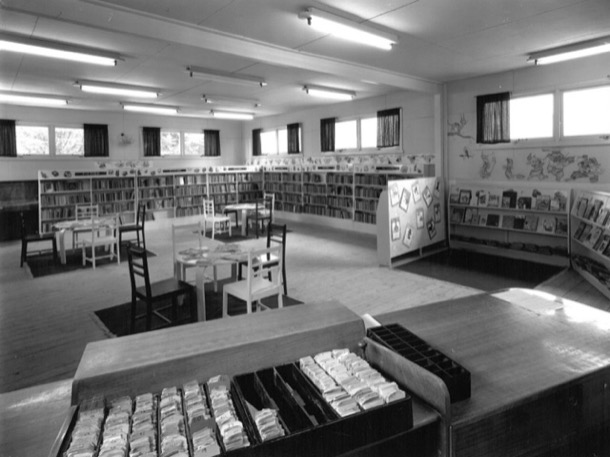

I vividly remember what I assume was a private, lending library coming to the house with blue covered hard back books for Mum and Dad to borrow. I remember the small van parked at the front door and the gentleman, clad in a fawn dust coat, bringing in the books and inserting the borrowing card in the pocket inside the back cover of items borrowed. We cannot find any reference to travelling lending libraries but we surmise that it may have been an offshoot of a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens. Public lending libraries were not established until the 1960s, in response to public pressure. Maybe when Mum and Dad lived with her parents they had all belonged to a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens, not far from Boronia Street, where they lived.

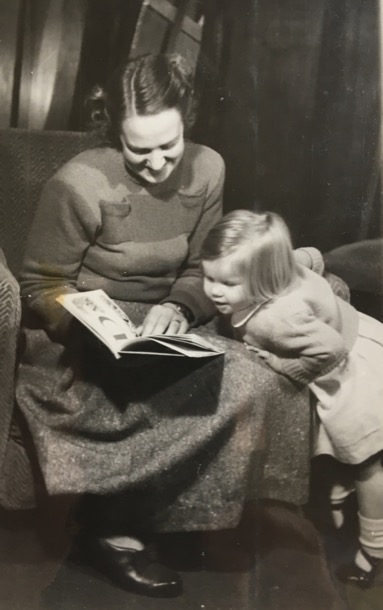

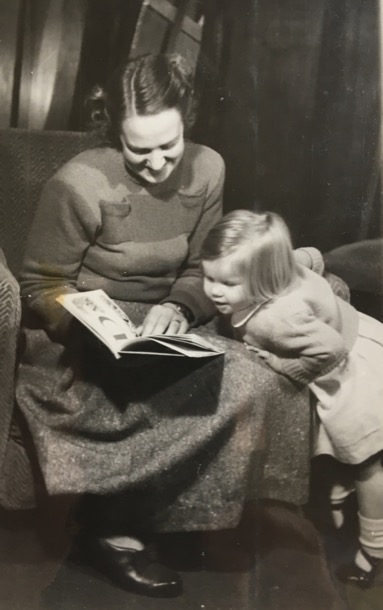

I loved having Mum read to me.

But Margaret was three years younger and her experience was completely different:

“I was just three when the next baby in line was born. He was premature and challenging, and we think our mother probably found the next few years a very difficult time.

In the years before he was born, she read to Sue, and I was there, but I don’t have much memory of it. I certainly don’t have the strong, warm connection to those books that Sue has. And when I was of an age where they would have been appropriate for me, Mum was caught up with managing the baby, and I was pretty much left to my own devices.

I remember, later on, her reading to our two younger brothers, perhaps when they were about three and five years old. But, by then I was reading for myself.”

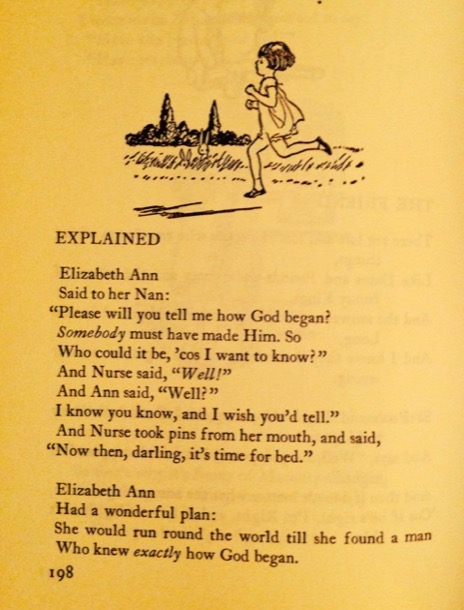

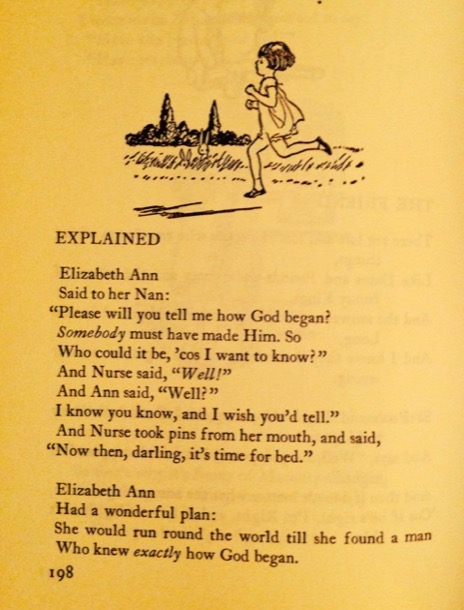

One of my earliest memories was of the A.A. Milne books. Milne wrote the story of Winnie-the-Pooh for his son, on whom the character of Christoper Robin was based.

We also had a vinyl record of the poems read by a man, with a very English accent of course. We must have listened to it hundreds of times, as Margaret and I can both recite The King’s Breakfast and some others, with exactly the same rhythm and expression.

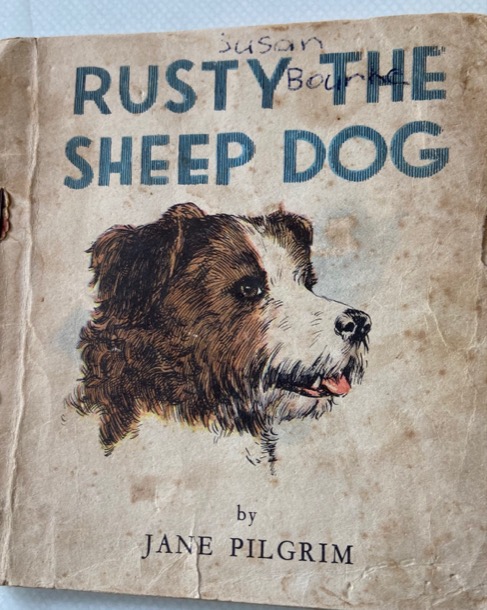

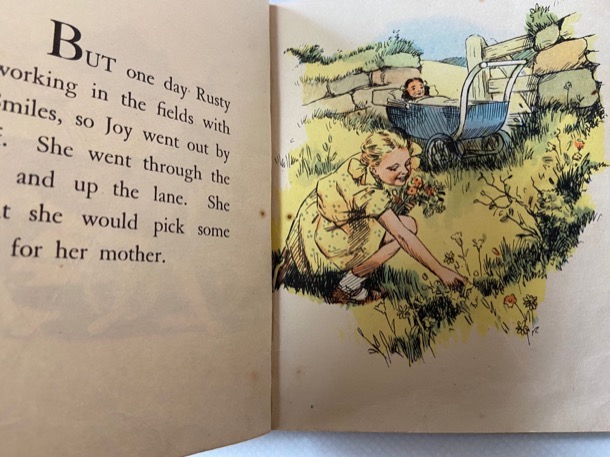

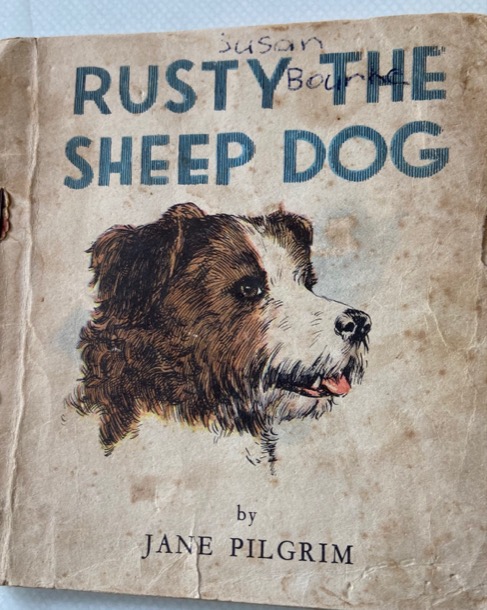

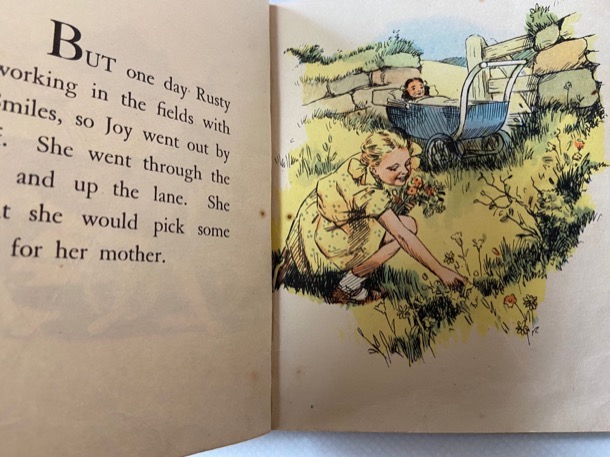

My other strong and pleasant memory is of Rusty the Sheep Dog, which is one of the Blackberry Farm series by English author Jane Pilgrim. Blackberry Farm is situated on the outskirts of an unnamed English village. The farm, a sheep and dairy property, is owned by Mr and Mrs Smiles, who have two children, Joy and Bob. Very proper, very white and very English.

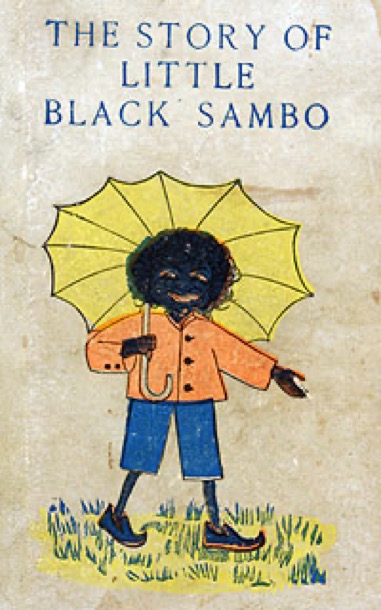

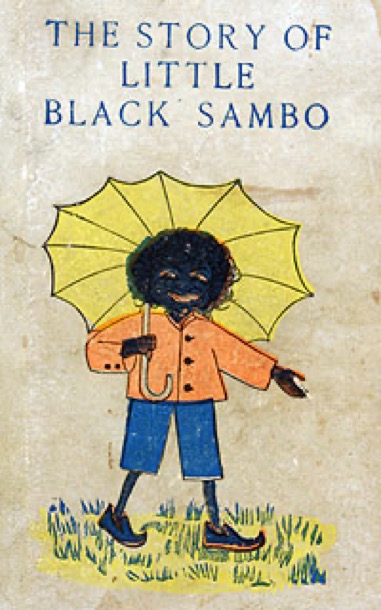

From this we graduated to Noddy and Big Ears complete with culturally inappropriate “golliwogs” and apparently a questionable relationship between Noddy and Big Ears. It all went over our heads, as did the racist overtones in Little Black Sambo. Black Sambo was a little Indian boy whose mother was Black Mumbo and father Black Jumbo.

Oh dear! Once again the stereotyping passed us by. Was it maliciously racist or a product of its times? After all, the author wrote and illustrated the book in 1889., in a Britain which had an imperialist presence in India and an Empire ‘on which the sun never sets’.

Our early schooling took place alongside a fair chunk of the population…. the baby boomers were growing up. It was still “post war” enough in the mid fifties for there to be a shortage of teachers. All this was dealt with by adding more and more desks - class sizes were massive!

The range of abilities in each class was, as always, vast. The single teacher was charged with teaching the more than fifty little souls in front of her how to read. There were no remedial classes, no gifted programs and no differentiated curriculum - sink or swim, and sit down and shut up!

At the time we were in the early grades at school, the “whole word” system was mandated. This has the goal of having “the children recognise the word as having a particular shape or contour, rather than decode the word based on individual letter sounds.”

We remember flash cards - words, phrases and then sentences, which, in sing song little unison voices, we “read”, as the teacher held each card up.

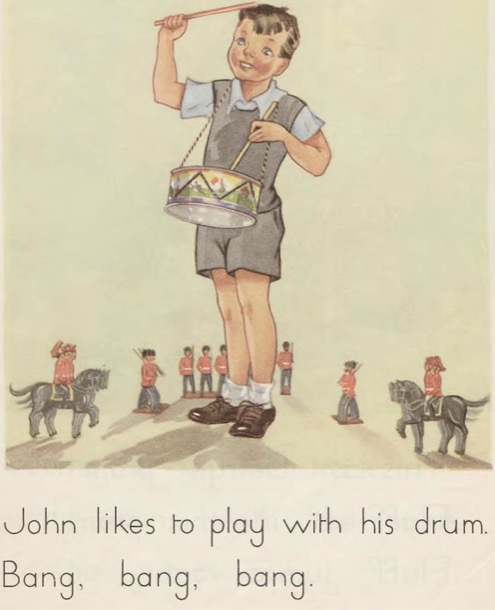

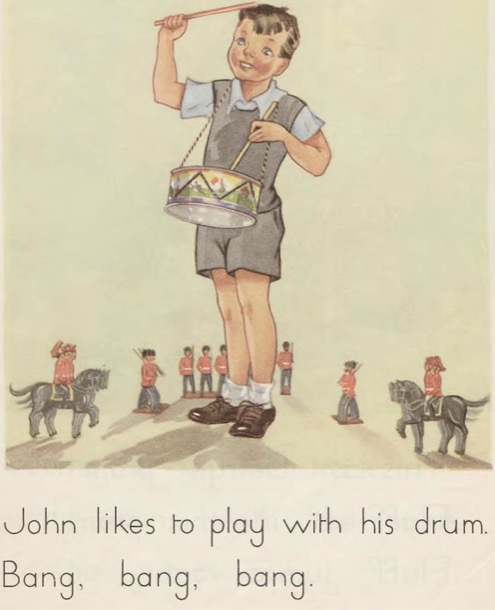

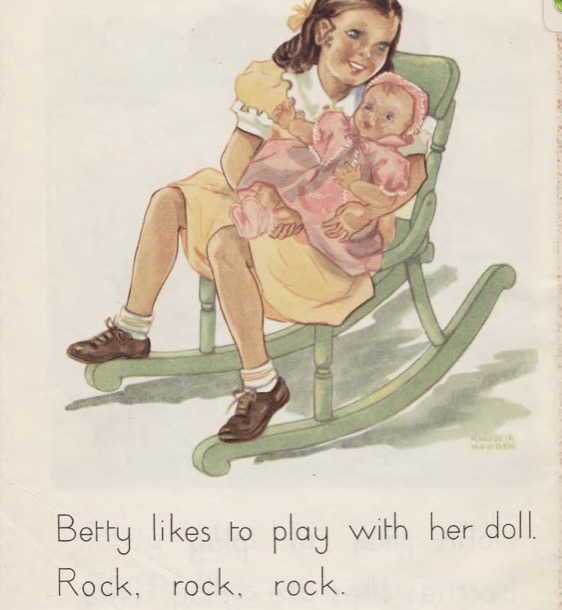

“John”

John likes”

John likes to play.”

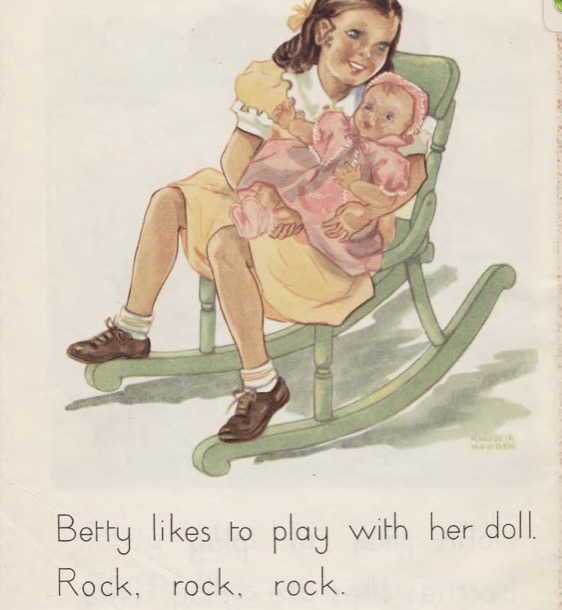

Then, eventually, we read the whole lot. John and Betty was a portrait of little siblings, stereotyped in every possible way one can stereotype!

My main memory of this time is … impatience. I don’t really know when the “being able to read” magic happened. I don’t think I could read before I went to school, but the whole process seemed very slow.

It seems we didn’t have access at school to other books, and I don’t remember reading books at home until a bit later. But I wanted to.

Eventually, enough of the class was deemed to be proficient enough at reading to read other things.

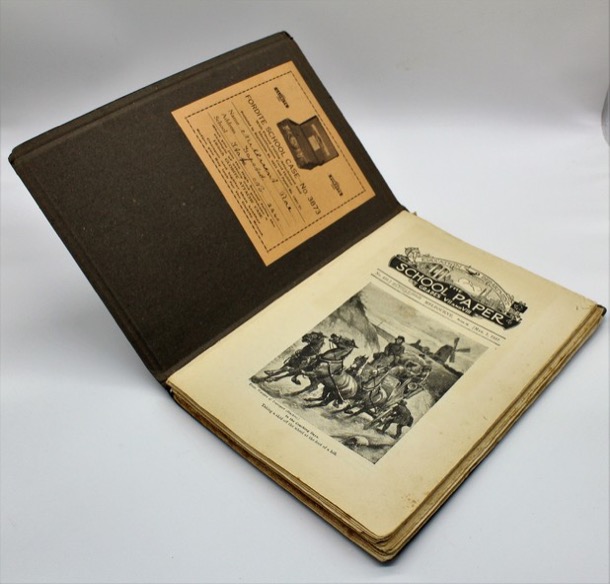

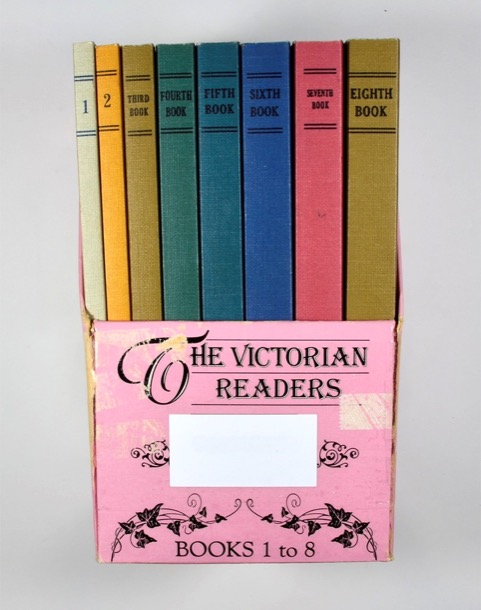

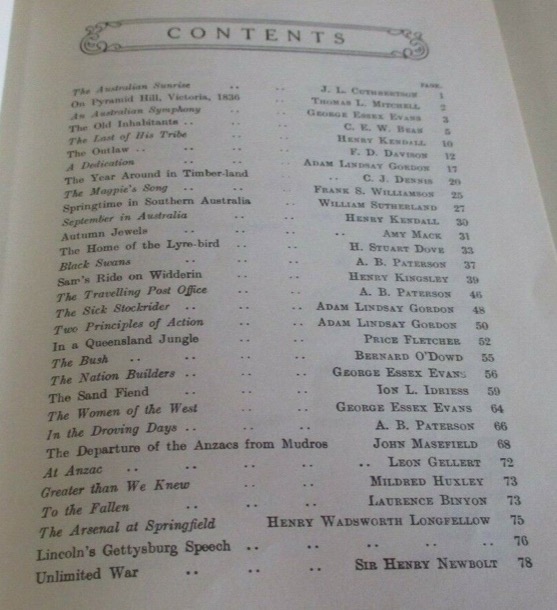

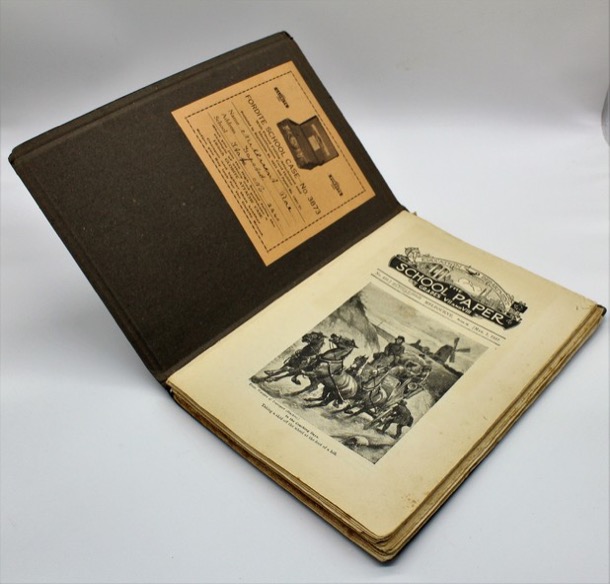

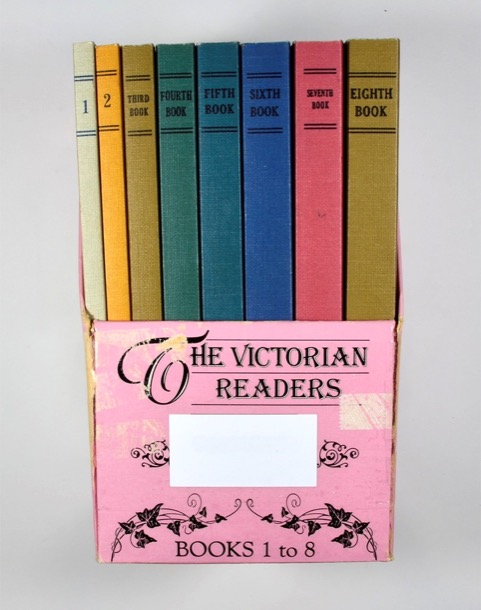

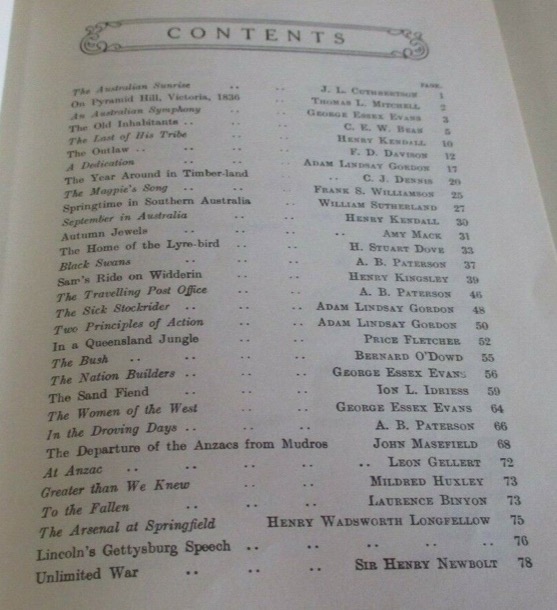

The School Paper, a monthly publication of the Victorian Education Department, was first introduced into Victorian schools in the 1890s.They were compulsory reading in schools until 1928, when the Victorian readers became compulsory and the School papers supplemented them. We remember both, and in our memory, the contents was interchangeable.

The school papers were foolscap sized, printed on fairly cheap paper. At the beginning of the year we all bought a black folder, stiffened cardboard with inner strings ready to contain the twelve issues for the year. Sue says she can remember the smell of the folders.

The readers are collections of stories, poems, illustrations and extracts from longer works, twenty-five percent of which had to be Australian. The rest has a very British flavour. The Australian content focused on white bushmen, pioneers, and settlers with a side serving of heroic Anzacs. The Australian landscape was sentimentalised, even while its “taming” was celebrated.

They are an insight into the values and culture that were being instilled into the population, and also into the standard expected at particular levels.

Clearly, quite a proportion of the class would have found the language incomprehensible, and the content alien.

We can only remember reading the School Paper and Victorian Readers at school. And we kept them in our school desk. Did we own our own copy? Did we have use of them just for the school year?

Once we could read, we had a limited, but much loved selection of books.

Enid Blyton was a staple, once again an English author. We particularly loved the Faraway Tree and Famous Five books. The Faraway Tree was a spreading oak, big enough to have small houses in the trunk. It grew in an enchanted forest and its branches reached up into magical lands, in which many of the adventures took place. Jo, Bessie and Fanny, very English children, share their adventures with the magical residents of the tree, such as Silky and Moonface.

The Famous Five also featured very English children: Julian, Dick, Anne and George [short for Georgina ] and their dog Timmy. Their adventures were much more serious and dangerous, sometimes involving criminals and lost treasure. The vast majority of the stories take place in the children’s school holidays, close to George's family home, Kirrin Cottage. The settings are almost always rural and the children picnic, bike ride and swim in the English and Welsh countryside: very wholesome.

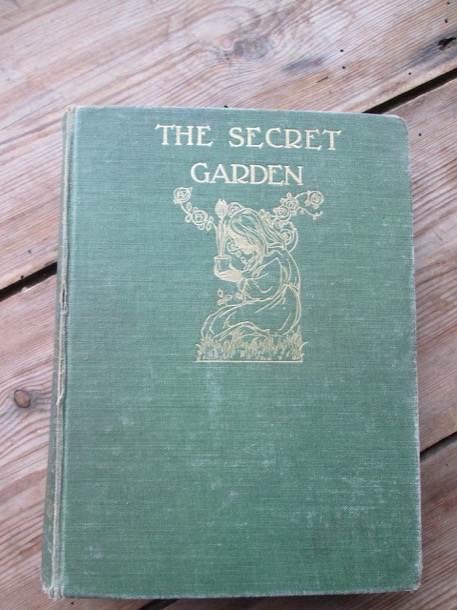

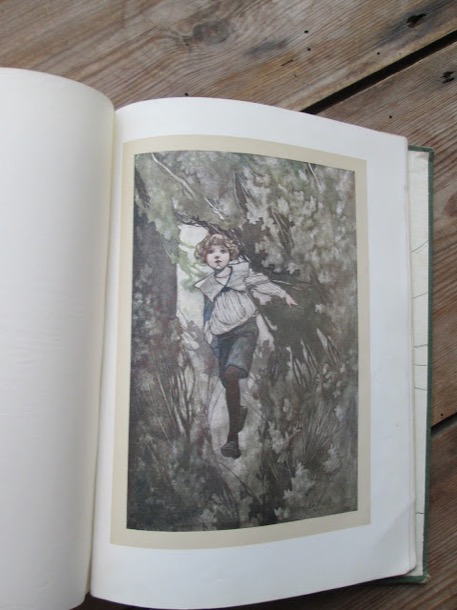

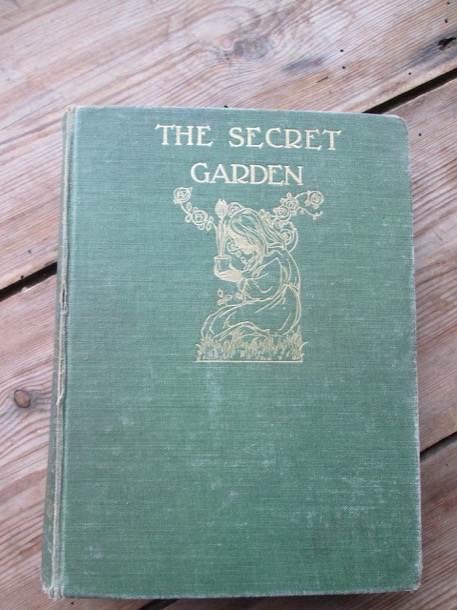

Our grandfather, Mum’s father, also revered books, many with English authors. When we were older we both remember borrowing his books such as George Elliot’s Mill on the Floss.This was a story of Tom and Maggie Tulliver, siblings who grow up at Dorlcote Mill on the River Floss. Another book from ‘the old country’ and a classic of English children’s literature was The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. We read Mum’s copy , a prize from school days. This story is set in a manor house on the Yorkshire moors where Mary Lennox is sent after her parents die in India. She has grown up in colonial India, surrounded by colour and life, and people who always do exactly what she wants, presumably Indian servants. This, like much of our reading matter, reeked of English privilege, class and the trappings of Empire.

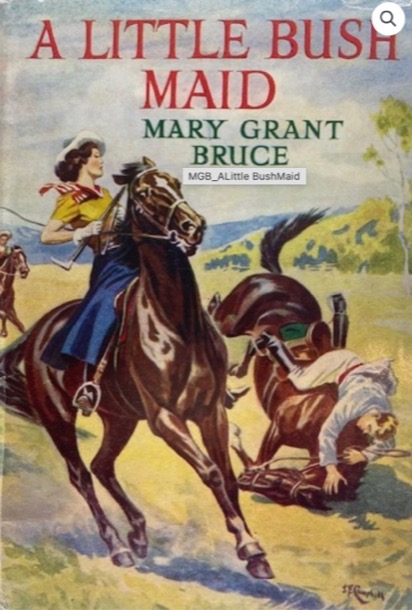

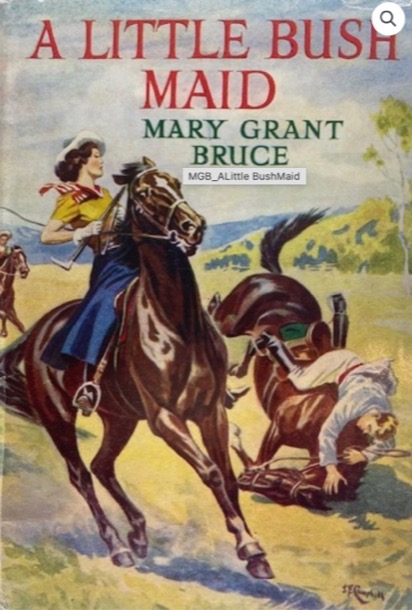

In this environment it is not surprising that Australian literature had similar characteristics. The Billabong books by Mary Grant Bruce, published in 1910, are a prime example. Very Anglo Saxon, gender specific and some would say racist, they represented to our young, innocent minds, adventure, and a glimpse into an idyllic life on a prosperous large property somewhere in Victoria. Twelve year old Norah, the ‘little bush maid’ lives at Billabong Station with her widowed father and brother Jim. Norah rides all over the property on her beloved pony Bobs, joining in the mustering and the “holiday fun” when Jim comes home from boarding school.

This sums up our own reaction to the Billabong books:

‘The Linton family are very much lords of their Australian manor, ruling in a benignly patronising way.The house, large enough to have ‘wings’, is staffed by a doting cook and various ‘girls’. The decorative front garden is maintained by a Scotsman, the vegetable garden and orchard at the rear are looked after by ‘Chinese Lee Wing (and oh isn’t his silly accent funny!) Numerous unnamed men work the farm itself with one of them, called Billy, seemingly assigned to be the children’s personal slave. Billy is never, ever described without with an adjective like “Sable Billy” or “Dusky Billy” or “Black”. And in case the reader hadn’t quite caught on, he is also variously described as careless, lazy or – just once – as a n——r. At 18 years of age Billy is older than the children and, according to Norah’s father, the best hand with a horse he’d ever seen, yet the children casually order him about and call him Boy. Billy, like every 18 year old bossed by a 12 year old girl, living without friends or family, and with no girlfriend in sight, seems perfectly content with his lot.

But, and sadly there always seems to be a but, my beloved Billabong books belong very much to the era in which they were written. Almost every writer I know cites Enid Blyton as one of their favourite childhood authors. She transported them in a way few other writers could. But almost every writer I know is also sorrowfully aware that once you’ve grown up there is no going back to Blyton’s magical worlds. The racism, the class barriers, the gender stereotypes are just too distressingly obvious to make Blyton an enjoyable adult read. And so it is for Billabong.’

Michelle Scott Tucker [Billabong Series, Mary Grant Bruce 2019]

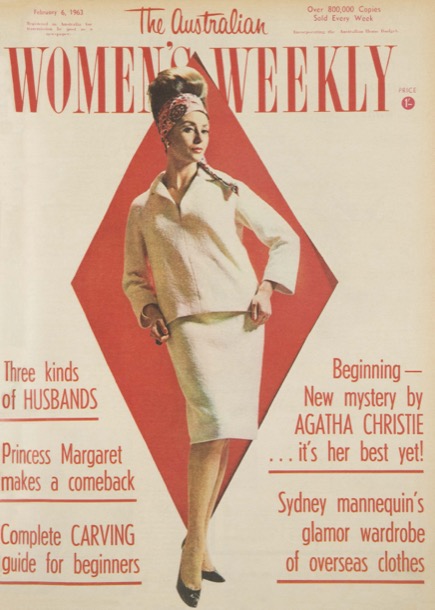

As well as books, there were magazines.

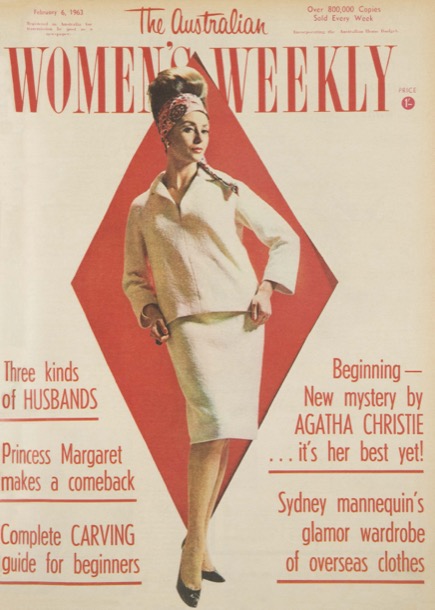

We struggle to remember exactly how frequently we got the Woman’s Weekly magazine. It came out weekly, until 1982, when it became a monthly. We think our mother must have bought occasional ones from the Wattle Park Newsagent. We don’t think we had a subscription, but it is a very clear memory.

It was an important window into Australian suburban culture.

We remember the sections:

Agony aunt, where people would write in asking for relationship advice.

Household hints

Letters

Knitting and sewing patterns

Fashion and make up advice

Recipes

Health items, discussion specifically about women and children

Probably some Hollywood celebrity items, but we don’t remember having much interest in those

Royals. That was much more our cup of tea. After all, our second names are the names of the late queen and her daughter.

… and of course the ads - mostly household items, fashion and make up.

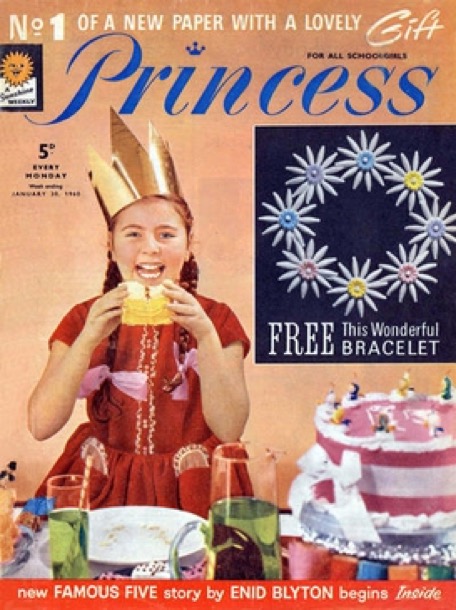

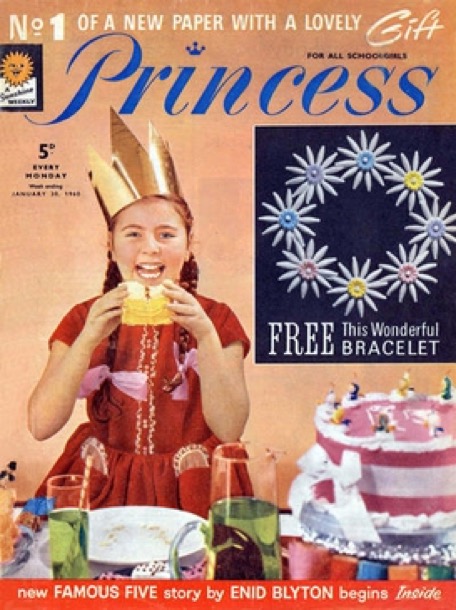

From January 1960, when I was eight and Sue was eleven, we had Princess magazine, a monthly English magazine, aimed at middle class girls. It contained stories, serials, factual articles, all with high quality photos and pictures. Ballet, horses and show jumping, fashion… the content did not have much to do with our own lives, but maybe that’s why we loved it. And there were free gifts!

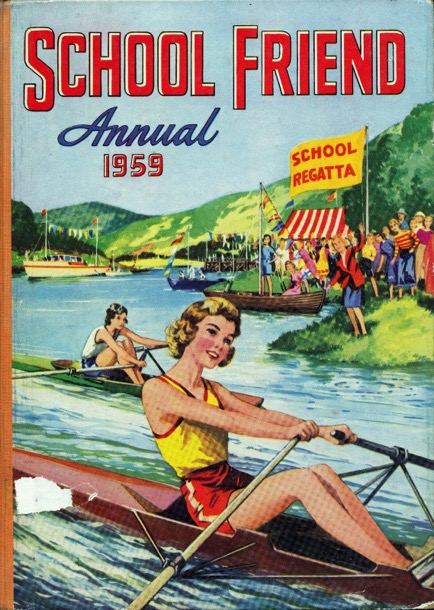

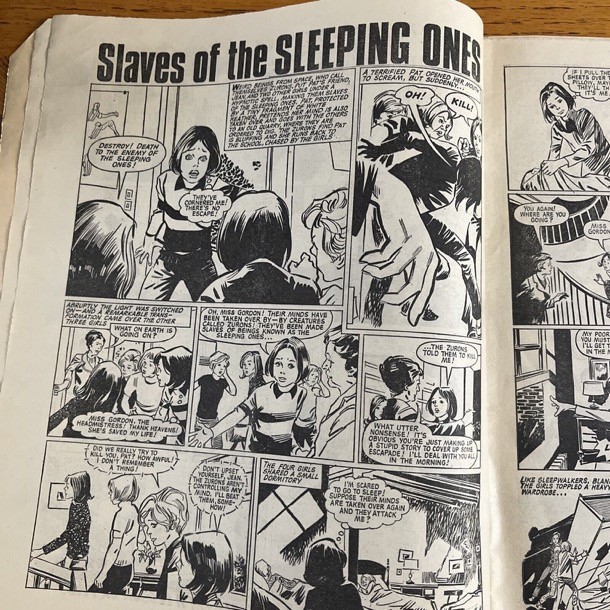

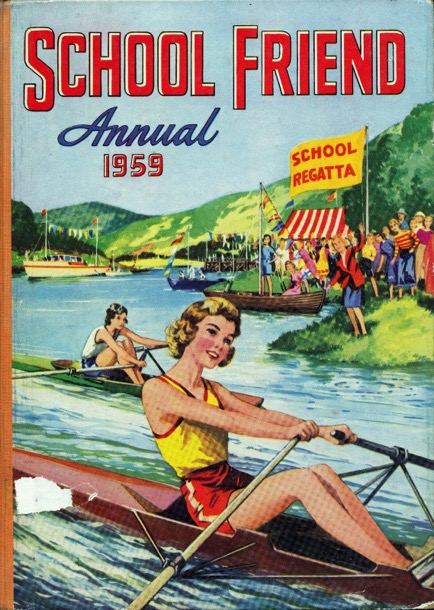

We also loved Schoolfriend magazine and Annuals.

‘Schoolfriend was about the exploits of brave, public school girls at boarding school in England, based on the adventures of pupils in a girls’ boarding school called Cliff House, and featured such characters as Barbara Redfern, Mabel Lyon, Jemima Carstairs – who wore a monocle and had an Eton crop’.

Although the stories featured scenarios in which most children wouldn’t have participated in the 1950s (horse riding, ballet, skiing in the Alps) there was an interesting message being spelled out: in a school environment devoid of males, females were able to assert themselves and reach their full potential.’

from https://johndabell.com/

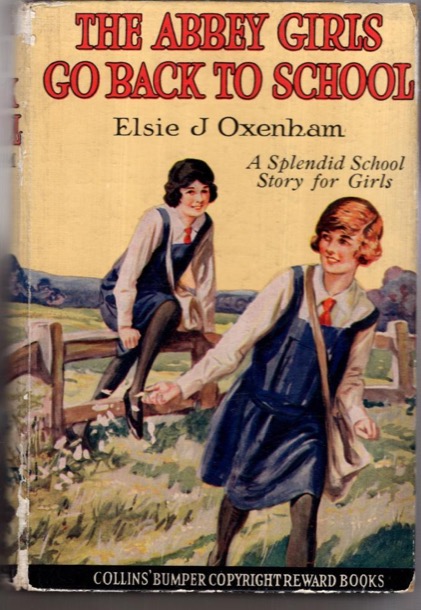

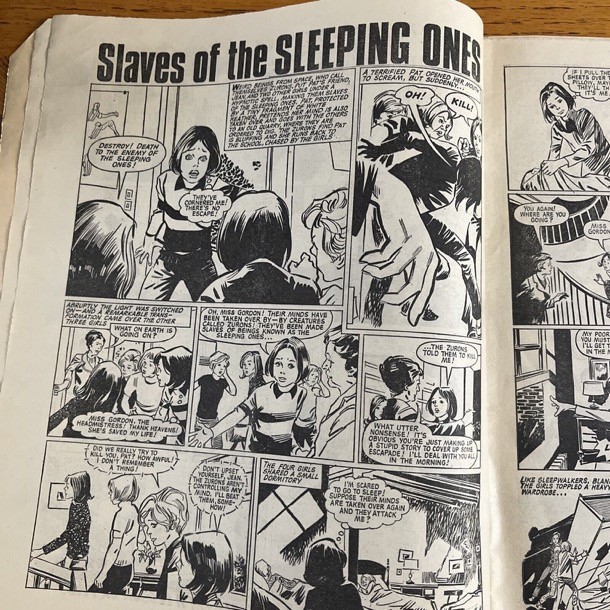

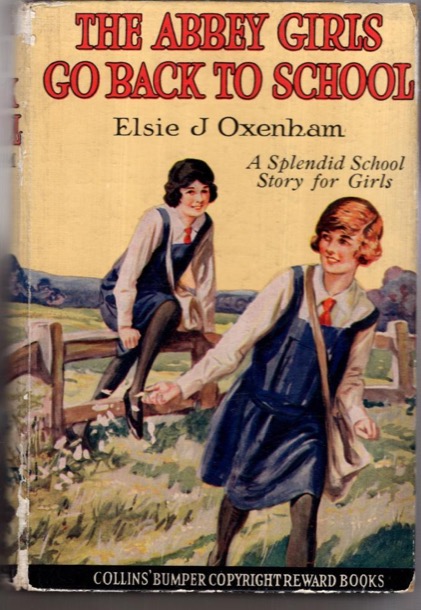

There were English Boarding School books, too.

During our annual six week Christmas holiday camping holidays, reading featured heavily.

My memory is of many nights with the family sitting around in the tent, under the central tilley lamp, wrapped in blankets, reading, in silence. When we look at the timing, it probably only happened for a few years, and it would not have included our little brothers, but it feels like a well established custom.

The books lived in a sturdy wooden box, the “book box”, which, Sue remembers, had dovetailed joints. In my memory, we all dipped into it. Maybe our younger brothers were in bed, or maybe they read other, more suitable books. We don’t remember them being read to.

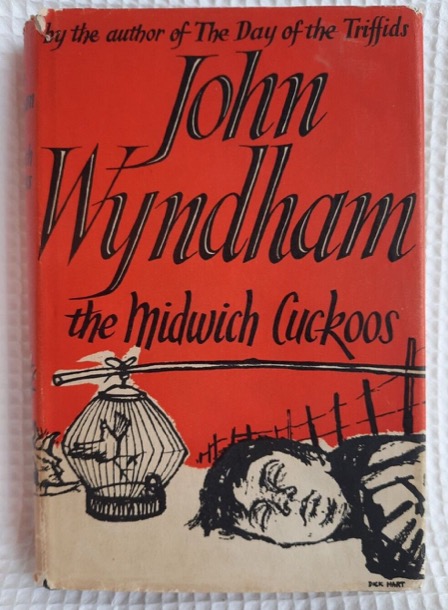

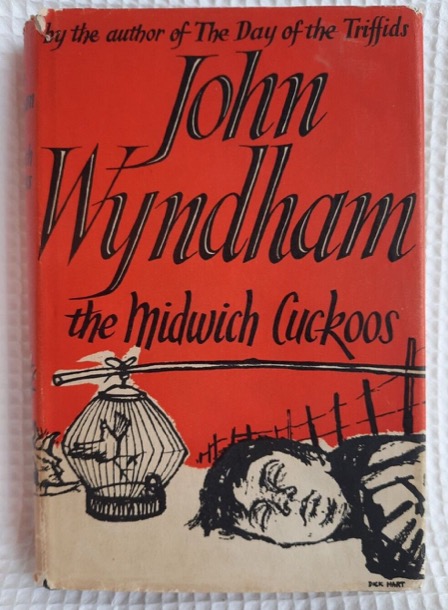

There were a lot of library books, but paper backs featured as well. A brainstorm yields: P D James, Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh and other “who dunnits”, Gerald Durrell’s family stories, AJ Cronin, John Wyndham’s Science fiction, Dr Kildare books.

In general, it’s holiday reading, and pretty light. We remember the books being mostly our father’s choice. There were some we didn’t like, such as Westerns, with pictures on the cover of cowboys on horseback. We don’t remember any censorship, but maybe it was subtle enough for us not to have noticed.

Camping holidays are the only time either of us can remember reading Mum and Dad’s books. We can’t ever remember not having access to books though. As a family we didn’t own many books, we all used the library.

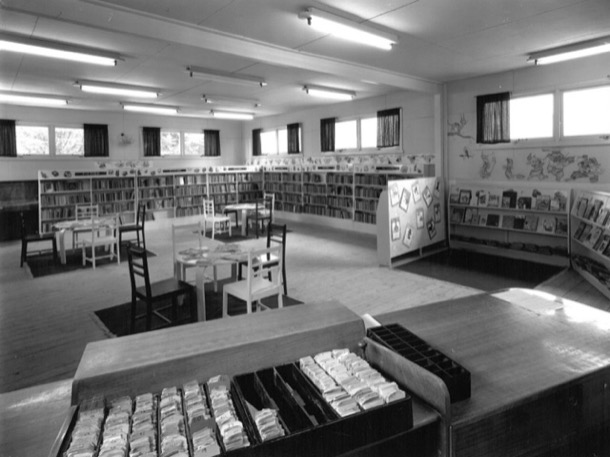

Visits to the Box Hill Junior Library were a regular feature in our childhood. The library was behind the Town Hall and was a very simple weatherboard structure, but inside it seemed there was a never ending supply of books. I never remember not being able to find a book I liked. Library visits must have been fortnightly as that was the borrowing period, so it is no wonder that I can still visualise the interior exactly.

The Billabong books were on the right just past the picture books, top and second shelf down. Once in the door, we would always make a beeline for that shelf to see if the next Billabong book was there. This was particularly important to me as I wanted to read them in order. Margaret does not remember this being a feature of her library visits.

We began this exploration of books in our early life full of the warm memories of specific titles. We already knew that, in our childhood, books were our escape, our entertainment and our cultural education. We buried ourselves in books, and we both remember many hours reading on our beds transported to other worlds.

Over the time we have been talking and writing about this topic, we have realised that the genre that most captured our imagination, and has remained as treasured memories, was actually quite narrow. It was characterised by adventure, characters who were resourceful and brave, often female, and idyllic settings. The action often happened in school holidays, sometimes on islands and beaches or Australian cattle and sheep stations.

We are also struck by the narrowness of the cultural values. We think of our family’s values as progressive, liberal and inclusive. We witnessed no open discrimination in our white suburban neighbourhood. And now, we are surprised at the extent of the sexism, class prejudice and racism in beloved books. It all went completely unnoticed at the time, but our adult, twenty-first century eyes look aghast at the world we immersed ourselves in.

We are three years apart, and our early childhood experiences are quite different. Despite the three year gap, when we read lists of books for little children, from those times, the same titles resonate for both of us.

As we became independent readers, home time meant being left much of the time to our own devices. The municipal library was our source of escapism, adventure and vicarious happiness.

I vividly remember what I assume was a private, lending library coming to the house with blue covered hard back books for Mum and Dad to borrow. I remember the small van parked at the front door and the gentleman, clad in a fawn dust coat, bringing in the books and inserting the borrowing card in the pocket inside the back cover of items borrowed. We cannot find any reference to travelling lending libraries but we surmise that it may have been an offshoot of a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens. Public lending libraries were not established until the 1960s, in response to public pressure. Maybe when Mum and Dad lived with her parents they had all belonged to a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens, not far from Boronia Street, where they lived.

I loved having Mum read to me.

But Margaret was three years younger and her experience was completely different:

“I was just three when the next baby in line was born. He was premature and challenging, and we think our mother probably found the next few years a very difficult time.

In the years before he was born, she read to Sue, and I was there, but I don’t have much memory of it. I certainly don’t have the strong, warm connection to those books that Sue has. And when I was of an age where they would have been appropriate for me, Mum was caught up with managing the baby, and I was pretty much left to my own devices.

I remember, later on, her reading to our two younger brothers, perhaps when they were about three and five years old. But, by then I was reading for myself.”

One of my earliest memories was of the A.A. Milne books. Milne wrote the story of Winnie-the-Pooh for his son, on whom the character of Christoper Robin was based.

We also had a vinyl record of the poems read by a man, with a very English accent of course. We must have listened to it hundreds of times, as Margaret and I can both recite The King’s Breakfast and some others, with exactly the same rhythm and expression.

My other strong and pleasant memory is of Rusty the Sheep Dog, which is one of the Blackberry Farm series by English author Jane Pilgrim. Blackberry Farm is situated on the outskirts of an unnamed English village. The farm, a sheep and dairy property, is owned by Mr and Mrs Smiles, who have two children, Joy and Bob. Very proper, very white and very English.

From this we graduated to Noddy and Big Ears complete with culturally inappropriate “golliwogs” and apparently a questionable relationship between Noddy and Big Ears. It all went over our heads, as did the racist overtones in Little Black Sambo. Black Sambo was a little Indian boy whose mother was Black Mumbo and father Black Jumbo.

Oh dear! Once again the stereotyping passed us by. Was it maliciously racist or a product of its times? After all, the author wrote and illustrated the book in 1889., in a Britain which had an imperialist presence in India and an Empire ‘on which the sun never sets’.

Our early schooling took place alongside a fair chunk of the population…. the baby boomers were growing up. It was still “post war” enough in the mid fifties for there to be a shortage of teachers. All this was dealt with by adding more and more desks - class sizes were massive!

The range of abilities in each class was, as always, vast. The single teacher was charged with teaching the more than fifty little souls in front of her how to read. There were no remedial classes, no gifted programs and no differentiated curriculum - sink or swim, and sit down and shut up!

At the time we were in the early grades at school, the “whole word” system was mandated. This has the goal of having “the children recognise the word as having a particular shape or contour, rather than decode the word based on individual letter sounds.”

We remember flash cards - words, phrases and then sentences, which, in sing song little unison voices, we “read”, as the teacher held each card up.

“John”

John likes”

John likes to play.”

Then, eventually, we read the whole lot. John and Betty was a portrait of little siblings, stereotyped in every possible way one can stereotype!

My main memory of this time is … impatience. I don’t really know when the “being able to read” magic happened. I don’t think I could read before I went to school, but the whole process seemed very slow.

It seems we didn’t have access at school to other books, and I don’t remember reading books at home until a bit later. But I wanted to.

Eventually, enough of the class was deemed to be proficient enough at reading to read other things.

The School Paper, a monthly publication of the Victorian Education Department, was first introduced into Victorian schools in the 1890s.They were compulsory reading in schools until 1928, when the Victorian readers became compulsory and the School papers supplemented them. We remember both, and in our memory, the contents was interchangeable.

The school papers were foolscap sized, printed on fairly cheap paper. At the beginning of the year we all bought a black folder, stiffened cardboard with inner strings ready to contain the twelve issues for the year. Sue says she can remember the smell of the folders.

The readers are collections of stories, poems, illustrations and extracts from longer works, twenty-five percent of which had to be Australian. The rest has a very British flavour. The Australian content focused on white bushmen, pioneers, and settlers with a side serving of heroic Anzacs. The Australian landscape was sentimentalised, even while its “taming” was celebrated.

They are an insight into the values and culture that were being instilled into the population, and also into the standard expected at particular levels.

Clearly, quite a proportion of the class would have found the language incomprehensible, and the content alien.

We can only remember reading the School Paper and Victorian Readers at school. And we kept them in our school desk. Did we own our own copy? Did we have use of them just for the school year?

Once we could read, we had a limited, but much loved selection of books.

Enid Blyton was a staple, once again an English author. We particularly loved the Faraway Tree and Famous Five books. The Faraway Tree was a spreading oak, big enough to have small houses in the trunk. It grew in an enchanted forest and its branches reached up into magical lands, in which many of the adventures took place. Jo, Bessie and Fanny, very English children, share their adventures with the magical residents of the tree, such as Silky and Moonface.

The Famous Five also featured very English children: Julian, Dick, Anne and George [short for Georgina ] and their dog Timmy. Their adventures were much more serious and dangerous, sometimes involving criminals and lost treasure. The vast majority of the stories take place in the children’s school holidays, close to George's family home, Kirrin Cottage. The settings are almost always rural and the children picnic, bike ride and swim in the English and Welsh countryside: very wholesome.

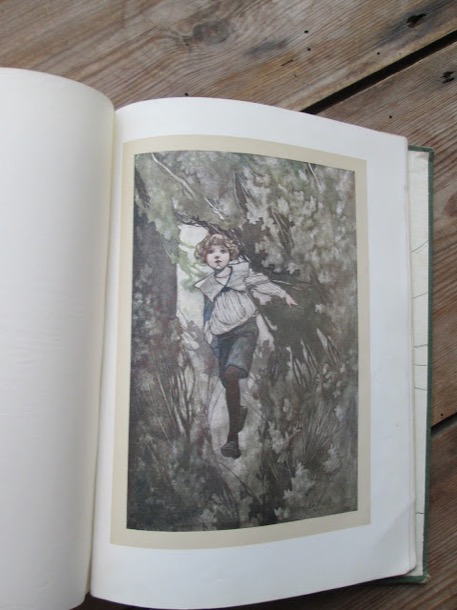

Our grandfather, Mum’s father, also revered books, many with English authors. When we were older we both remember borrowing his books such as George Elliot’s Mill on the Floss.This was a story of Tom and Maggie Tulliver, siblings who grow up at Dorlcote Mill on the River Floss. Another book from ‘the old country’ and a classic of English children’s literature was The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. We read Mum’s copy , a prize from school days. This story is set in a manor house on the Yorkshire moors where Mary Lennox is sent after her parents die in India. She has grown up in colonial India, surrounded by colour and life, and people who always do exactly what she wants, presumably Indian servants. This, like much of our reading matter, reeked of English privilege, class and the trappings of Empire.

In this environment it is not surprising that Australian literature had similar characteristics. The Billabong books by Mary Grant Bruce, published in 1910, are a prime example. Very Anglo Saxon, gender specific and some would say racist, they represented to our young, innocent minds, adventure, and a glimpse into an idyllic life on a prosperous large property somewhere in Victoria. Twelve year old Norah, the ‘little bush maid’ lives at Billabong Station with her widowed father and brother Jim. Norah rides all over the property on her beloved pony Bobs, joining in the mustering and the “holiday fun” when Jim comes home from boarding school.

This sums up our own reaction to the Billabong books:

‘The Linton family are very much lords of their Australian manor, ruling in a benignly patronising way.The house, large enough to have ‘wings’, is staffed by a doting cook and various ‘girls’. The decorative front garden is maintained by a Scotsman, the vegetable garden and orchard at the rear are looked after by ‘Chinese Lee Wing (and oh isn’t his silly accent funny!) Numerous unnamed men work the farm itself with one of them, called Billy, seemingly assigned to be the children’s personal slave. Billy is never, ever described without with an adjective like “Sable Billy” or “Dusky Billy” or “Black”. And in case the reader hadn’t quite caught on, he is also variously described as careless, lazy or – just once – as a n——r. At 18 years of age Billy is older than the children and, according to Norah’s father, the best hand with a horse he’d ever seen, yet the children casually order him about and call him Boy. Billy, like every 18 year old bossed by a 12 year old girl, living without friends or family, and with no girlfriend in sight, seems perfectly content with his lot.

But, and sadly there always seems to be a but, my beloved Billabong books belong very much to the era in which they were written. Almost every writer I know cites Enid Blyton as one of their favourite childhood authors. She transported them in a way few other writers could. But almost every writer I know is also sorrowfully aware that once you’ve grown up there is no going back to Blyton’s magical worlds. The racism, the class barriers, the gender stereotypes are just too distressingly obvious to make Blyton an enjoyable adult read. And so it is for Billabong.’

Michelle Scott Tucker [Billabong Series, Mary Grant Bruce 2019]

As well as books, there were magazines.

We struggle to remember exactly how frequently we got the Woman’s Weekly magazine. It came out weekly, until 1982, when it became a monthly. We think our mother must have bought occasional ones from the Wattle Park Newsagent. We don’t think we had a subscription, but it is a very clear memory.

It was an important window into Australian suburban culture.

We remember the sections:

Agony aunt, where people would write in asking for relationship advice.

Household hints

Letters

Knitting and sewing patterns

Fashion and make up advice

Recipes

Health items, discussion specifically about women and children

Probably some Hollywood celebrity items, but we don’t remember having much interest in those

Royals. That was much more our cup of tea. After all, our second names are the names of the late queen and her daughter.

… and of course the ads - mostly household items, fashion and make up.

From January 1960, when I was eight and Sue was eleven, we had Princess magazine, a monthly English magazine, aimed at middle class girls. It contained stories, serials, factual articles, all with high quality photos and pictures. Ballet, horses and show jumping, fashion… the content did not have much to do with our own lives, but maybe that’s why we loved it. And there were free gifts!

We also loved Schoolfriend magazine and Annuals.

‘Schoolfriend was about the exploits of brave, public school girls at boarding school in England, based on the adventures of pupils in a girls’ boarding school called Cliff House, and featured such characters as Barbara Redfern, Mabel Lyon, Jemima Carstairs – who wore a monocle and had an Eton crop’.

Although the stories featured scenarios in which most children wouldn’t have participated in the 1950s (horse riding, ballet, skiing in the Alps) there was an interesting message being spelled out: in a school environment devoid of males, females were able to assert themselves and reach their full potential.’

from https://johndabell.com/

There were English Boarding School books, too.

During our annual six week Christmas holiday camping holidays, reading featured heavily.

My memory is of many nights with the family sitting around in the tent, under the central tilley lamp, wrapped in blankets, reading, in silence. When we look at the timing, it probably only happened for a few years, and it would not have included our little brothers, but it feels like a well established custom.

The books lived in a sturdy wooden box, the “book box”, which, Sue remembers, had dovetailed joints. In my memory, we all dipped into it. Maybe our younger brothers were in bed, or maybe they read other, more suitable books. We don’t remember them being read to.

There were a lot of library books, but paper backs featured as well. A brainstorm yields: P D James, Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh and other “who dunnits”, Gerald Durrell’s family stories, AJ Cronin, John Wyndham’s Science fiction, Dr Kildare books.

In general, it’s holiday reading, and pretty light. We remember the books being mostly our father’s choice. There were some we didn’t like, such as Westerns, with pictures on the cover of cowboys on horseback. We don’t remember any censorship, but maybe it was subtle enough for us not to have noticed.

Camping holidays are the only time either of us can remember reading Mum and Dad’s books. We can’t ever remember not having access to books though. As a family we didn’t own many books, we all used the library.

Visits to the Box Hill Junior Library were a regular feature in our childhood. The library was behind the Town Hall and was a very simple weatherboard structure, but inside it seemed there was a never ending supply of books. I never remember not being able to find a book I liked. Library visits must have been fortnightly as that was the borrowing period, so it is no wonder that I can still visualise the interior exactly.

The Billabong books were on the right just past the picture books, top and second shelf down. Once in the door, we would always make a beeline for that shelf to see if the next Billabong book was there. This was particularly important to me as I wanted to read them in order. Margaret does not remember this being a feature of her library visits.

We began this exploration of books in our early life full of the warm memories of specific titles. We already knew that, in our childhood, books were our escape, our entertainment and our cultural education. We buried ourselves in books, and we both remember many hours reading on our beds transported to other worlds.

Over the time we have been talking and writing about this topic, we have realised that the genre that most captured our imagination, and has remained as treasured memories, was actually quite narrow. It was characterised by adventure, characters who were resourceful and brave, often female, and idyllic settings. The action often happened in school holidays, sometimes on islands and beaches or Australian cattle and sheep stations.

We are also struck by the narrowness of the cultural values. We think of our family’s values as progressive, liberal and inclusive. We witnessed no open discrimination in our white suburban neighbourhood. And now, we are surprised at the extent of the sexism, class prejudice and racism in beloved books. It all went completely unnoticed at the time, but our adult, twenty-first century eyes look aghast at the world we immersed ourselves in.

Comments

Family camping

07 09 16 14:51 Filed in: Children 1950s | Teenagers 1960s

Our grandparents and parents had camped as young adults, so living in third world conditions in order to be able to enjoy ‘the bush’ was not a new pastime in our family.

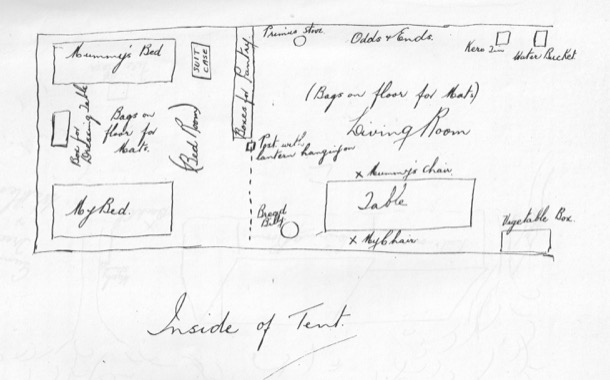

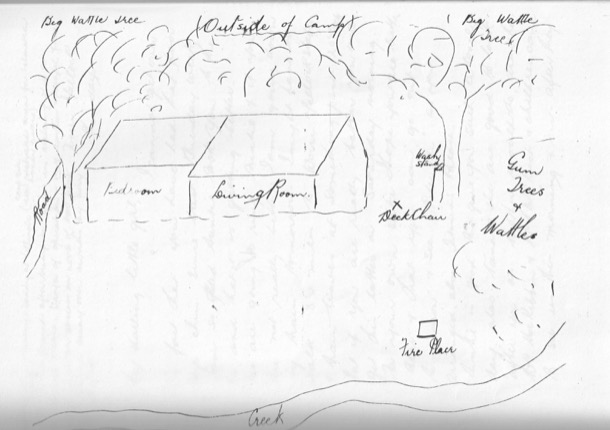

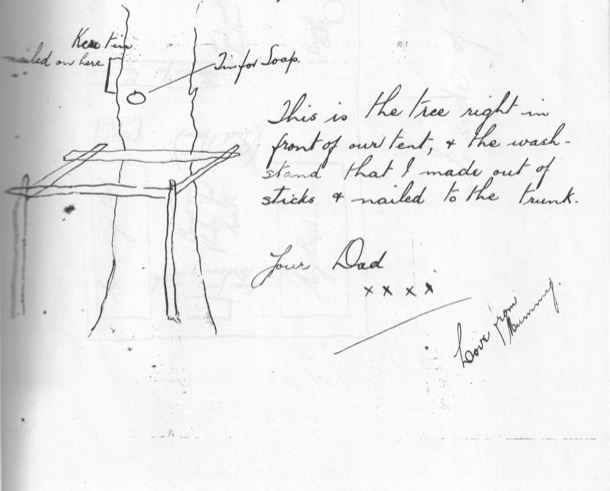

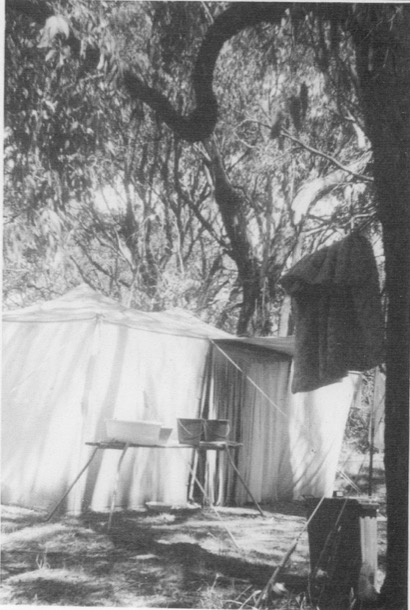

In January 1935, Alf and Alfreda, camping in the bush by the Yellingbow Creek in Woori Yallock, sent letters back to their daughters. In them Alf drew pictures of their camp:

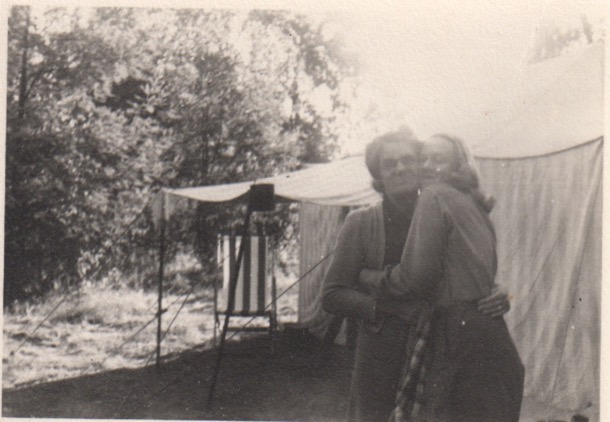

And Alice as an adult, camping with her parents:

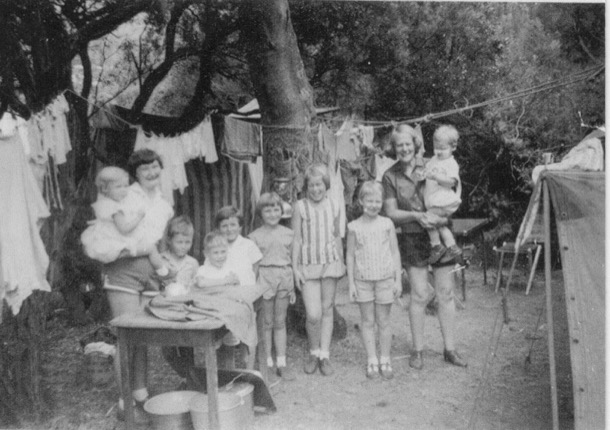

Our parents, Jim and Alice, went camping too:

1958 and we kids embarked on our lifetime of camping. It was very exciting. We went to the Prom with the Lees, a family of five who lived at the end our street. We hired a big canvas tent, a simple square and most of the cooking was done outside. I remember this holiday vividly. We all had a wonderful time swimming in the river and the sea and walking. We even all made it to the top of Mt Oberon.

One memorable day there was much preparation for the ‘heat wave’ with temperatures over 100 degrees. Yes, fahrenheit, we are old! A picnic lunch was planned and we waded over the river with supplies for the day. The shady little beach on the other side was the perfect spot for a hot day but i am sure we all managed to get sunburnt. No sunscreen in those days!

That holiday must have been a great success as preparations were made the following year for Christmas holidays to be spent at a new place Mum and Dad had found with the Wilkinsons, a family from the Church. So began the long summer holiday tradition of going to Shoreham.

One of the important purchases that has remained in both our memories was the tent. As we were short of money our parents decided to buy an Army surplus tent. We went to Williamstown to pick it up. In those days driving to Williamstown involved a ride across the mouth of the Yarra on a punt that took a few cars at a time: so interesting that Margaret wrote a Grade 2 Composition on the very subject. Here it as as written:

‘On Sunday we went to hire a tent. It was a very long way. The place we hired the tent from was called Williamstown. On the way we saw many ships and boats. Also we saw a rubbish tip where our Australian rubbish is tiped. When we go there we pressed a button and a man came out. Then we went to buy some icy-poles. When we got back I asked Mummy what a man was doing, Mummy said he was drunk, I said ‘OOOOH’ He herd music playing and wanted to get in. He was knocking and waving then he touched his hat took it off and put it on a man’s knee. Then we had a ride on a queer ferry. which parted from the road.‘

It was a huge heavy old tent, khaki with big black letters and numbers stencilled on the roof. it was rather dark inside and it LEAKED.

Next year Dad’s Uncle Austin died intestate. As he was unmarried, his estate was divided between his relations. The law does not cut people from wills for marrying Protestants so Dad received his share. What a lucky windfall! It enabled us to buy a smart new tent that did not leak and was light and airy

Shoreham Foreshore Camping Ground was on a bushy small promontory on Western Port Bay. It was part of a sleepy small holiday place still surrounded by small farms. There were not a vineyard in sight. The camping sites were well spaced and some were quite secluded. The bookings were done through Mr Webb who was the Ranger and lived in a house abutting the camping area. Water was available in three large water tanks near our site. There were several toilet blocks where, in the morning, a small queue of brunch-coat clad ladies could be seen snaking its way up the hill. Pastel shades and floral prints were the predominant choice of fabric.

No showers though. Apart from swimming nearly everyday, a bath in the baby’s bath had to suffice.

Our tent was divided into three rooms: two for sleeping, equipped with double bunks, and a general living and kitchen space. We also had a flywire annexe where we had a camping table for meals. The floor, which covered the whole interior, was made from chook food bags we had sewn together on the back lawn. It became quite flat over the years and always smelt pleasantly of chook food pellets.

While Mum was sewing our summer shorts and tops, Dad used to come down a week early and set up camp. It was quite a trailer load and a big job as we had a big wooden chest of drawers, double bunks a two burner gas stove with a griller, chairs, table and an old ice chest. The iceman used to come to the camp ground so we could always keep food cold. In later years we moved onto a gas fridge. A week later we would descend with clothes, food, Christmas presents and a big wooden box of books all ready for a blissful six weeks of beach, shuttlecock, 500, reading and fun.

The book box was quite a feature and sat in the central living space. Dad raided the school library and we all borrowed the maximum from the Box Hill Library. We always had a wonderful collection to choose from. There were often a number of books in series such as A.J. Cronin's series on the life a young doctor in a Welsh mining village in the 1920s and many Who Dunnits. Great absorbing reads that we all looked forward to.

Another of the memorable, nightly rituals was the lighting of the Tilley. Tilleys are kerosene fuelled pressure lights that give out a tremendous amount of white light and therefore were terrific to read by. The lighting ritual was impressive to young eyes as it involved a flaming ‘thing’ that was clapped around the stem of the Tilley. Once the mantle was heated and glowing and the flame had subsided pumping began and we waited with bated breath until the mantle popped and was a light.

Dinner and washing up would be done and so nightly activities could begin. Often wrapped in rugs we settled down to reading or, more often than not, 500 tournaments. It was great fun.

One wet day game was for Ian and Margaret to embarrass our mother by pretending she was hitting us. We would howl and scream “Pleeeease don’t hit me Mummy! Oh no you’re hurting him!” You get the idea. She would be torn between laughter and horror. Tents have thin walls and we were surrounded by other camping families. Sue even remembers the game extending to shadow play on the tent walls at night. She remembers coming back from the toilets and seeing the acted out scenes of horrific violence. It’s a bit sobering now to consider that some of the “audience” in other tents may well have experienced that violence in their lives for real!

Shoreham has a rocky promontory, exposed at low tide. Then it was too shallow to swim, so we kids spent the time turning over rocks to see the creatures scuttle away, as we walked way out on the rocks. Quite a long way out was “the rock pool”. It was big enough and deep enough to swim in. There was a flat rock at one end which was the “diving board”. The pool was full of waving sea weed, tiny fish, sea horses, anemones. This gave it an exotic, scary atmosphere. Jumping off the diving board and seeing how far we could swim underwater was a favourite game there.

The rocks seemed the same every tide. Year after year we kids clambered roughly over them, caught crabs, and sea urchins, took interesting creatures back to the tent, collected shells.

Sometime over the decades, Shoreham’s bio diversity diminished. There are still crabs, and a few anemones, but the sea horses and sparkly fish are gone.

One year, Ian, aged perhaps seven or eight, turning over one of those rocks, dropped it on his finger. There was lots of blood, huge drama, and a trip to the doctor in Hastings to have it stitched. Sue remembers she and I walking him back to the campground, each of us with an arm around him and Sue with her palm outstretched underneath the finger. She was sure it was about to drop off. I remember feeling very sorry for him because he was not allowed to go in the water for the whole rest of the summer.

Low tide exposed enough flat wet sand for French Cricket. This was organised by the fathers. Everyone played, but we girls really only tolerated it and weren’t very good.

Dad, Ian, Chris and a couple of Wilkinsons:

The worst thing about low tide was the sea grass. There were crabs scuttling through its waving fronds and if you swam over it, instead of risking your toes, eventually you felt it on your bare legs and arms and you simply had to stand up.

At high tide Shoreham had wonderful swimming. We would stay in for hours with our poor mother sitting on the beach keeping watch. Sometimes you had to share the water with drifts of dead sea grass, which would pile up in smelly cliffs as the tide went down again.

When our parents could be bothered taking us, we would walk around to the surf beach at Point Leo. Here we could body surf and jump around in the big waves. Later we even had a couple of blow up rubber “boards, like a small lilo with handles. The price you paid for playing in the surf was having to walk back with your bathers full of wet sand. I remember fearing that the wad of sand must have looked as if I’d pooed my pants.

Shoreham beach looking towards Point Leo:

In the other direction was Flinders and the ocean. The view of Flinders from Shoreham was of a long promontory. The Naval Base there used to have gunnery practice, evident to us by puffs of smoke and a distant “whomp whomp”.

Flinders in the far distance:

Weekdays involved walking to “the store”. Shoreham had a general store on the edge of the foreshore reserve. Dad and the four kids would walk up along the track, buy The Age, milk and whatever else was needed, even a Drumstick sometimes:

Then we would head along the main road to the Post Office. We took it in turns to go in and ask for “Any letters for Bourke?”. Then we would walk down the post office road to the beach track. Some days we would continue to follow the road past some holidays houses and then rejoin the campground track, but most often we would climb down the steps alongside “Camel’s Hump” and back along the beach. In my memory these steps were steep, treacherous and dangerously slippery. Back at camp Mum would be doing piles of holiday washing all by hand, after lugging the water from the tank and heating it up on the gas stove.

Most years, for one day, usually when it was not beach weather, we would pack a lunch and “walk to Flinders”. Mostly we walked both ways along the beach, making the Flinders pier the turnaround point, but sometimes we came back by the road, and bought fish and chips at the Flinders shop. It was an eight mile round trip, (about thirteen kilometres). The beach between Shoreham and Flinders, mostly deserted and wild, had a succession of small coves and rocky headlands. The first headland, covered in pine trees, separated the camp beach from “Shoreham Proper”.

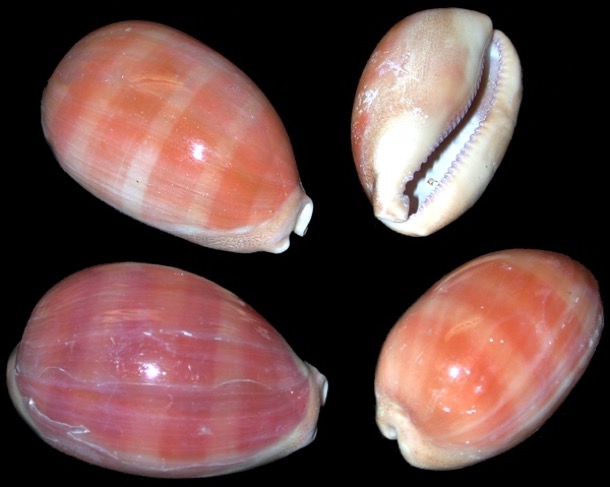

Walking any distance along the beach included shell collecting. There were lots of interesting and colourful shells but the most prized were the cowries. It was not uncommon for each of us four kids to have twenty in our collection by the end of the summer holiday. We would also collect sea urchins, trapped in amongst the piles of dead sea grass.

I never understood the pleasures of sun baking, but would spend hours in the water. Our noses were zinc creamed, but not our shoulders. It must have been hard for our mother who was responsible for managing four children’s sun exposure. We were often sunburnt and sometimes even had blisters.

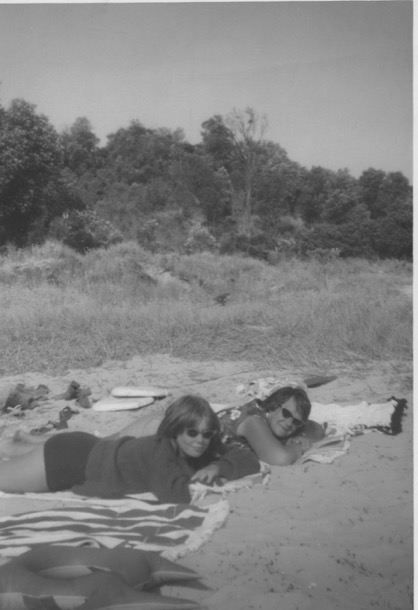

Sue and Mum in the sand dunes:

On the six or seven Sundays we were at Shoreham we would dress in the “good” clothes we had brought especially, and shoes (the rest of the time we wore thongs or sandals), and drive to Flinders Presbyterian Church. The Wilkinson family came too. Sue remembers the prickly feeling of a dress on sunburnt back and the resentment of having to go. The church was small and dark and had a small regular congregation. Afterwards we would pile back into the car and race back to the beach.

As the years went on and we went to Shoreham every summer, it became the way I measured the passing years. It was a benchmarking time. The tent set up, the beach, the bush all stayed the same. The people changed gradually, inexorably. Summer holidays was the time to recognise and celebrate this.

This clearly happened for the adults as well. I can remember Alan Wilkinson, chatting to our mother, oblivious of nearby children, the way adults were in those days. “I’m turning forty this year, Al. It’s hard, life’s passing me by.”

By the time I was fourteen I was spending Saturday nights during the year at local church dances. I don’t remember how it came about, but I remember going that summer to a surfer dance at Point Leo Surf Club. This was the time of Little Pattie and Col Joy. Wonderful music in my opinion. I remember a hot, dusty room full of blond suntanned kids, all moving in sync to a band playing covers. The surfy dance was ridiculously simple:

There were always more boys than girls at Shoreham over the summer. Only boys actually surfed. I remember a “date” with a boy who had a car. It was mortifying at first, when my mother insisted that Sue came with us because I was too young, and probably mortifying for her to have to be the chaperone, but I don’t remember where we went, so it can’t have been too bad.

Sue also had romantic episodes at Shoreham. One year she met a fellow camper, who was a Year 12 student doing a navy cadetship. She spent time in Melbourne that summer holidays, doing a “life drawing” course and went out with him over that summer:

Around the same time Dad and I were involved in a prank at the YMCA camp. Over the summer holidays there were crowds of young boys with older teenagers as camp leaders. I guess Dad might have got talking with the adults at the camp and hatched the plan.

Would I like to be involved? What, you mean walk alone into a room full of a hundred boys having dinner, find the mark, the shyest of the leaders, who has never seen me before, sidle up to him and put my head on his shoulder and snuggle up to him? Try and stop me!

After a few minutes, Dad appeared at the back of the room, brandishing a gun (!) “Where’s my daughter?” he howled.

I don’t remember what happened next, but I have a strong impression of being the only girl surrounded by a crowd of boys and loving it!

Our earlier experience of the YMCA camp was attending the outdoor “pictures”. Campers, each carrying a folding chair, would head off after dinner to the camp and set up facing the strung up bed sheet, amongst all the camp boys.

Shoreham camp was a social place for the adults as well. The same families would camp in the same sites each year, including a few we knew from our real lives. I remember late afternoons on the beach sitting in a group of Bourkes and Wilkinsons, ten kids between us, reluctant to break the spell of the setting sun and then going back to our tent and cooking dinner for fourteen. We had day visitors too, family and friends. I remember Mrs Moss, also a church friend of Mum’s, enormous and perfumed. I remember being impressed after I had complimented her on her dress, when she demurred and pointed out that she didn’t have “her corsets” on.

When the holidays ended we were brown as berries. Packing up was done and then home to the strange sensation of hard floors under our feet and the new school year.