Fire and Storm

MY COUNTRY By Dorothy MacKellar

‘I love a sunburnt country,

A land of sweeping plains,

Of ragged mountain ranges,

Of droughts and flooding rains.

I love her far horizons,

I love her jewel sea.

Her beauty and her terror,

The wide brown land for me.

Margaret and I learnt this iconic poem during our respective Grade 6 years and many of its lines are still etched in memory. In fact we can still recite much of it with exactly the same intonation and expression. This poem, written in 1904, captures the tenor of our post, Fire and Storm.

Fire, still very much part of our lives, has also been part of our family history.

BLACK THURSDAY 1851

The first reference to fire was in1851 with the fire known as ‘Black Thursday’.

Painting by William Strutt

This was the first catastrophic bushfire faced by white settlers in Victoria. The lead up to the fire followed what is now a familiar pattern of events. Reports at the time said that there had been wet years of lush growth followed by severe drought, leaving the bush and long grass tinder dry. Thursday the 6th of February dawned hot and windy, and the fires took off, leaving one quarter of the state black and smouldering. Our antecedents, the Bourke’s of Pakenham, were caught up in the fires in a dramatic way. Shortly before Black Thursday the Bourke’s had taken possession of Bourke’s Hotel in Pakenham. Michael Bourke remained at their selection, while Mrs Bourke was to run the hotel and Post Office.

‘On Black Thursday the whole district was ablaze. Mr Bourke was trying hard to save the station property. Water having been exhausted, milk was brought into play and ultimately the run was saved. Word was brought to him that the hotel property at Pakenham was surrounded by fire. Galloping down there, he found his wife and her children had saved themselves by crouching in the water in the bed of the creek.’

We took this photo of the exact spot, during our visit to Pakenham.

BACCHUS MARSH FIRE 1928

From an article in ‘The Argus' Thurs 12th July 1928

"FIRE AT BACCHUS MARSH.THREE SHOPS DESTROYED"

This was a report on the fire suffered by our grand parents, Alf and Alfreda, in which they lost almost everything, but escaped with their lives. We heard dramatic stories of this fire in childhood and is told below by Marge and Alice on the tape they made in 1990.

The hardware shop was their business, and they had gone out on their own, in an already a difficult time of their lives. Aunty Bert was staying with them to help out, as was her role in the family, as the unmarried sister. Auntie Bert, Alf and Alfreda would have been in their early thirties,Alice was five and Marge three years older. Thank goodness Bert was there as she seems to have had a cool head and took action to get everyone out as the fire took hold.

Marge and Alice’s recollection is fairly accurate, as the newspaper report comments on the strong North wind and the poor water pressure that hampered the fire fighting.

The Argus reports that at one stage,

…. the premises of Mr. G. H. Anderson were threatened , but this danger passed, with a change in the direction of the wind, A good portion of the stocks of Messrs. McLaren and Coates was saved, but considerable damage was done to Mr. Phillip’s stock. It is understood that all buildings and stock, except that of Mr. McLaren, were insured.

At half-past 7 o'clock, in the morning the fire was under control, and all that was left of three of the shops were the walls.’

Mr McLaren may have been uninsured but Alf was definitely not, as he had been unable to pay the insurance. They lost nearly everything.

We had wondered about Alice’s comment about Auntie Bert’s friend Nell Pearce, whose family took them all in after the fire, and yes it was a large and impressive brick house, still standing today:

As Alice states the Pearces were an influential family in the town. They had been an early pioneering family in the area. They built and established the General Store that presumably was very profitable, supplying the miners on the way to the Goldfields as well as the local community. The family then went into farming and other small businesses, and were influential in civic affairs.

Auntie Bert maintained a lifelong friendship with Nell, and neither of them married. I remember Nell Pearce being a name mentioned in conversation and I have a vague recollection of her as an imposing figure. I also remember her at Auntie Bert’ s sewing rooms in Camberwell. She was probably there for a fitting. Little did we know the history behind that friendship.

After cleaning up and sorting our their affairs Alf and Alfreda, the girls and presumably Auntie Bert left Bacchus Marsh and stayed with Grandpa and Grandma Holm in Surrey Hills. Alf then got a job in Croydon as manager of the hardware shop, where they spent many happy years.

BLACK FRIDAY 1939

After the 1851 fires, bush fires occurred in many parts of the State with predictable monotony. The next major statewide fire was in 1939, once again after a prolonged drought. High temperatures and strong northerly winds fanned separate fires that eventually combined and created a massive fire front that swept mainly over the mountain country in the northeast of Victoria, and along the coast in the southwest.

Lilydale Brigade 1939.

Source - CFA Website

More than two million hectares were burnt in the 1939 fires.They lasted for a week. Many, unable to be controlled, were left to burn out.

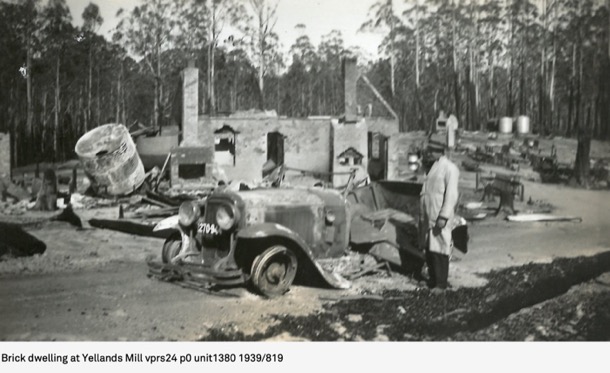

Yellands Mill, where 15 men died:

The extensive damage to over two million hectares of farmland and forest, not to mention the loss of livestock and lives, prompted a Royal Commission. They were tasked with examining the causes of the fire and making recommendations for future management.

The Royal Commission’s specific recommendation was that the various Bush Brigades, and Country Fire Brigades be amalgamated to form a single organisation to fight fire on private land outside the Metropolitan Area. The Forest Commission was responsible for fire on public land and the Metropolitan Fire Brigade was responsible for fire in the Metropolitan Area. Instead of a myriad of uncoordinated small brigades these three organisations were responsible for fighting fires in Victoria.

EARLY BUSHFIRE EXPERIENCE - MARGARET

My first memory of wildfire is of a fire on the empty block next door. The vegetation was sparse: weeds and gorse, with patches of bare clay.

We think it was around 1955. Sue doesn’t remember it, and was probably at school. But I have a clear memory and so I was probably at least four. The image in my mind is of mum, armed with a hessian bag, beating flames. Hessian is a coarse, rough brown fabric made from jute, widely used for packaging. We had a supply of hessian bags, saved from buying bulk chook food. Mum was not a “bush woman” in the Henry Lawson image, but she would have seen this form of fire fighting, and she apparently felt able to take it on.

Fire fighting with a hessian bag.

I don’t remember bush fires being a big part of my life as a child, until I was eleven, in 1962. That year was a big bushfire year in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs: 32 people died and 450 houses were lost. Areas affected included Mitcham, less than ten kilometres away from our place. We were never in danger in suburban Box Hill South, but there would have been a red glow in the sky, and the vivid memory I have of burning gum leaves falling in the back yard, is probably from this fire.

In 1979, I moved to the Dandenong Ranges, where the CFA had much more of a presence, and bushfire awareness was part of everyday life over Summer.

In those first few years, there was still on old dugout just over the road in the forest. It had a wooden sign “Dugout” and what looked like a large wombat hole. A closer look revealed a heavy grey army blanket hanging over the entrance. During a fire, this would be kept wet. Inside was a rounded cave, with earthen floor, ceiling and walls. It would have held a maximum of six adults. There was a metal bucket and a pile of musty grey wooden blankets. I guess it might keep you safe while a canopy fire raced overhead, but I wouldn’t want to rely on it.

The CFA were, and still are, omnipresent. On weekends they collect donations at major intersections. On Good Friday, and in the week before Christmas, they drive through the streets, playing piped music and rattling collection tins. Their sirens regularly echo through the Hills. We can hear the Belgrave, Upwey and Kallista sirens from our place, and sometimes all three will go off. In the past, the siren was used to call in the volunteers, and on a set night of the week, on CFA practice night, they would test the siren at a set time. We like that the sirens are still used, not so much as a specific warning, but as part of our aural landscape.

Nowadays, when we hear a siren, we go straight to the Victorian Emergency app, to check what has happened. Often it’s a house fire, a car accident, a small bush fire. During the Summer months we are more attuned to the sound. Our practice has long been to evacuate on days of dangerous fire weather.

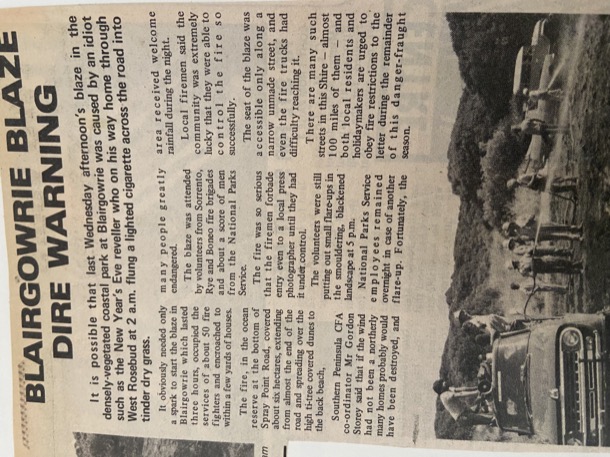

BLAIRGOWRIE FIRE 1980 - SUE

My only experience of fire first hand, was in 1980 at Janey’s house at Blairgowrie. We had all just sat down to lunch. Anna was nearly three and I was pregnant with Thomas. Everything was tinder dry, as it was January and we were in the middle of the 1979-1983 Eastern Australian Drought.

Halfway through lunch there were loud knocks at the door, and a panicking young man asked us for a hose, as he has seen a small fire beginning to build on the Spray Point Road, just fifty metres from the house. Jono and Janey raced down to investigate, but realised that they had not a chance of stopping the fire. It was spreading quickly, fanned by a strong north wind. This was a stroke of luck as this meant it was spreading away from us and towards the beach. We called the CFA who responded promptly, parking several fire trucks at the hydrant on the nature strip.

We were told to block the downpipes with oranges, fill the gutters with water, and shelter inside. The fire was brought under control fairly quickly but not before six hectares of the National Park was burnt.

It would have been a different story if the wind had changed and pushed the fire towards Janey’s house and of course all the other houses.

Local newspapers at the time reported on the fire and issued warnings and advice to residents and holiday makers for the rest of the holiday season that was only just beginning.

ASH WEDNESDAY

SUE

On Ash Wednesday I was at home with Thomas, as Anna had just started school. Thomas was happily playing with water in the shade of our pergola, as it was a very hot day. A nasty north wind intensified as the day wore on and many fires started across Victoria. I was listening to the ABC afternoon show hosted by Tony Delroy, who, as fires broke out, was reporting the outbreaks in real time. He also took many calls from people desperate for information. There were no centralised communications hub, warning system, or, of course, mobile phones. As the fires continued to burn during the evening and that night, the radio was the only source of state wide information. The 3LO radio hosts worked on a roster system to get the information out.

Since its inception the ABC had been responsible for emergency broadcasting, but only on the news bulletins.. In 1997 Ian Mannix was appointed as Program Director for Local Radio Victoria. He changed the nature of emergency broadcasting during the 1997 bush fire in the Dandenong Ranges. The fires burnt for days, three people died and forty homes were destroyed. Mannix asked the CFA for advice on what to say to to listeners ‘who were confronted with flames.’…Interestingly, the CFA had no experience of giving warnings and had never written a warning for people at risk.

Mannix went ahead and took the lead in creating the ABC’s approach to emergency broadcasting. He developed guidelines that included warnings at set intervals, including bush fire alerts for low level fires and urgent threat warnings for more serious fires. The system used in Victoria was expanded nationally after Black Saturday in 2009. Further recommendations were made by the Black Saturday Royal Commission that future refined and expanded the warning systems to television and commercial radio.

From this pioneering work by Ian Mannix, we now have an Australia wide warning system, and broadcasting training and guidelines in each state.

Ian Mannix oversaw the development and implementation of these systems and deservedly received the Australian Public Service Medal in 2012.

MARGARET

The first actual fire we had to deal with in Belgrave was the 1983 Ash Wednesday.

The name “Ash Wednesday” is nothing to do with ash from bushfires. It’s a historical/religious reference. It happens every year, and it marks the beginning of Lent, leading up to Easter, in lots of Christian denominations. It follows Shrove Tuesday, Mardi Gras … the last day of feasting before the deprivations of Lent. The ‘ash’ is sprinkled onto heads or swiped across foreheads as part of the Ash Wednesday service.

1982 had had a very droughty Winter, Spring and Summer. The little creek that runs through the forest over the road had almost stopped, and underfoot the leaves crackled.

The 1983 Melbourne dust storm, when 50,000 tonnes of Mallee topsoil turned the sky dark brown across the city, happened in early February. For me, it hit as I was crossing Burwood Highway on my way to the Ferntree Gully hotel, for an after school cool drink. The dust cloud was over 300 metres high and 500 kilometres long, and darkened the sky for an hour. It’s one of those iconic events where everyone can tell you where they were when it hit.

Image credit: Katsuhiro Abe/BOM

There were many fires that Summer. The CFA across Victoria attended nearly 3,200 fires. Wednesday February 16th was particularly hot and windy.

That morning I had woken feeling nauseous and weak. I rang in sick, and went back to bed. Within a few weeks, I would find out that this had been the beginning of morning sickness. Michael was born that October.

Later in the day I had a phone call from a friend who lived locally, suggesting I might consider leaving, as he had heard there was a fire in Belgrave Heights. Outside was stifling. My neighbour was packing her car but she was expecting to wait and see. I don’t remember having any sense of danger, though, later, we learnt that it was only the late afternoon wind change that stopped the fire from sweeping through Belgrave township and on to our place.

Photo: Tonia Van der Dungen. Christmas Hills CFA

Wind changes during bush fires dramatically widen the fire front, and this one swept through Belgrave South and on to Cockatoo and Upper Beaconsfield.

I don’t remember this, but apparently Ian and Lois were visiting me that day. Lois was pregnant with Sam who was born that winter. Ian speaks of driving home in the afternoon, and taking the sudden decision to drive straight on through Belgrave, rather than the more logical route through to Belgrave South. This would have been exactly the time of day when the fire swept through across the road they would have been on.

Later there were many stories, horrifying and heroic. In Cockatoo, 300 people sheltered during the night in the kindergarten, as a handful of local men kept the flames and embers at bay, saving many lives.

Across Victoria, 75 people died, more than 200,00 hectares were burnt and 2000 homes and buildings were damaged.

Friends from the suburbs rang to check that I was ok. Our little patch of the Dandenongs was untouched, but one didn’t have to drive very far to see the black horror.

Photo: Critchley Parker Junior Reserve. Upper Beaconsfield CFA

Ten years later, I began teaching at Monbulk College, and some of our students were still affected by their experiences in 1983. My friend and colleague Sarah had her Year 8 English class make a booklet marking the ten year anniversary. Everyone had stories, which the students typed up and put together. It remains an important part of the history of Dandenong Ranges, and other affected parts of Victoria.

The tragic Ash Wednesday fires were like those of 1939 Black Friday in intensity, if not in range. They confronted the modern firefighting community with the limits of its capacity and technology. Among the 75 dead, 17 firefighters died that day, some of them next to their well equipped tankers on a forest road in Upper Beaconsfield, when the wind changed and the firestorm swept over them. Changes in firefighting strategies and philosophies were inevitable. The community needed to be better informed and more involved. This is certainly my experience. I was so naive and ignorant, compared to what we expect from Hills people nowadays! There was a huge Royal Commission.

It seemed, as the Commission heard people’s Ash Wednesday stories, that the most dangerous situations people faced were from hurried departures. People died in their cars, not their homes. But the CFA could not guarantee to be there during huge bush fires, protecting every home.

And then there were stories of people actively defending their homes from ember attacks, and saving them. “People save houses. Houses save people.” was the mantra.

The “stay or go” policy began to be developed. As the professionalisation of firefighting, and the ‘Science’ of fire behaviour developed, ordinary people’s anecdotes were often disregarded as over hyped and hysterical.

There was a huge campaign to teach the population about how to prepare their homes, and defend them. Because it was so centralised, the people who lived on the edges of grasslands and those, like us, in what nowadays we call the “flame zone”, were given the same advice. The “go” part of “stay or go” felt like an afterthought for people who were not able bodied. I remember some of our neighbours’ plans were that the men and older boys would “stay” and the women and little children would “go”.

In 1987 the very first General Achievement Test had as one of its tasks information about how to prepare a home for bushfire. It was clearly in the zeitgeist.

My personal experience of this policy is encapsulated by a CFA Fireguard group meeting, in the years leading up to 2010, that we attended on our neighbour’s verandah. The CFA man explained patiently about how bushfires behave, and how we should be preparing our houses, so that we could defend them. The expectation was clearly that we and our neighbours would stay, in the case of a bushfire, and, with mops and buckets of water, we would put out any embers that threatened out house. We pointed to the towering ash forest, metres from our house, and told him we didn’t think our house would be defendable. He was not impressed.

Throughout the Millennial drought, from 1997 to 2009, during the most severe summers, we kept a trailer full of things at Chris’s parents’ place, and had a very clear plan. We evacuated quite a number of times, staying in their spare room. The plan was to insure fully, and simply not to be there during dangerous times. The local schools built fire refuges, and the CFA kept on with its “stay and defend” message. Water saving advice was everywhere. Like many others, we set up a grey water system to water our garden.

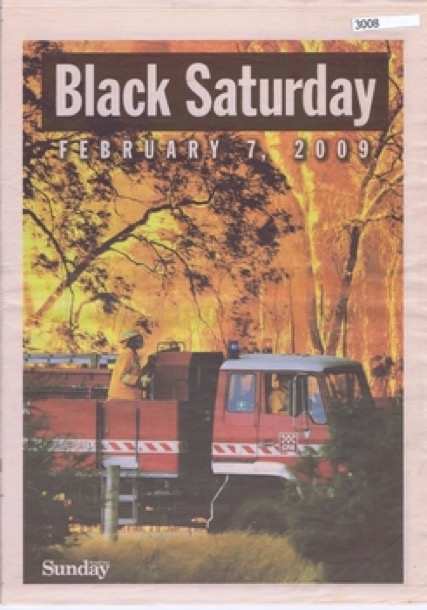

BLACK SATURDAY - MARGARET

And then came the summer of 2008-9. It had been particularly dry and hot. This was the summer when tree fern fronds were scorched, lawns died and record high temperatures were broken day after day. The forecast for the first week of February looked horrendous in advance, with temperatures of 48 degrees forecast, and Chris and I decided to take ourselves camping by the Thurra river, and wait it out. I was glad to be retired by then!

We followed the news of Black Saturday, on the radio, and, once the cool change hit, we packed up and drove out along the Thurra Road, as news of the death toll mounted. Along the Princes Highway, we saw fire fighters’ camp sites with row after row of little tents. The air was smokey, and through the Latrobe Valley we drove through a blackened landscape. At home, the garden was scorched and everything still crackled underfoot.

Back with television coverage, we watched interviews with people who had miraculously survived, saw footage of people’s fire refuges that had been easily breached, and heard the stories of person after person, traumatised by their unsuccessful attempts to defend their homes. 173 people had died, 120 of them in the Kinglake area. More than 450 hectares had burned and 3500 buildings, 200 of them houses, had been destroyed.

Herald-Sun

That cool change was not the end of the 2009 fire season. We evacuated a number of times that February. One day, a fire bug lit a fire just up the hill from us. I was sitting outside, and heard the crackle as flames licked up a nearby gum tree. Chris was walking in the forest. As I drove down to the Belgrave carpark, he was walking quickly back down through the forest, having seen the smoke. When he met a wall of flames, he backtracked hastily, headed toward the road, and hitched a ride with a stranger to near home. The wind was blowing the danger away from our place. I have been mocked mercilessly for my paper post it note on the door telling him I’d gone to the Belgrave car park, but at least he knew that I was out of danger.

In the car park, a gaggle of us watched the Elvis fire bombing helicopters head up the hill, and cheered, and very soon the whole drama was over.

2009 marked the end of the Millennial drought years. Summers since then have been cooler and wetter. But the legacy has been an obsession with rainfall figures, forecasts and climate outlooks.

Our local community facebook page has a member who is a forecaster with the Bureau of Meteorology, who posts every time there is a weather anomaly. It is clear from the responses to him, that we are not alone in our anxiety about rainfall.

THE BIG STORM - MARGARET

It was winter, 2021. There had been yet another Covid lockdown, this one lasting two weeks, finishing on June 10th. Life quickly went back to normal for most people in Melbourne.

But for us in the Dandenongs, the evening of June 9th, and the next morning, brought a massive windstorm which brought down huge swathes of trees, many across roads and onto 112 houses. The wind came at 120kph, but it came from an unusual direction, and our shallow rooted mountain trees were largely untested from that direction. They fell, roots and all, in their hundreds.

Even though the power went off immediately, and all the mobile towers were out, there were 9,500 calls for help logged by the SES. People were trapped in their houses, and many streets, including Michael and Katherine’s were blocked off. There was no way of communicating, in or out, for many days.

My most vivid memory of the storm comes from early on the morning of the tenth. Chris was standing with a view to the north of the forest out the window. His eyes widened, and yet another a great crash came from the forest. He had watched a two hundred foot tall mountain ash eucalypt gracefully fall sideways, taking down another tree of similar size, which in turn took out another one. Like enormous dominos, the three of them had joined the huge pile of previous victims on the forest floor. Later on we stood on the road, looking down where they had fallen and counted thirteen giant trees lying in a messy tangle.

Elsewhere in the Hills, this carnage had been repeated in town after town. We lucky ones who still had homes, watched with dismay as the power company’s estimates of power restoration stretched out beyond a week. Eventually we were able to drive out. It was a weird feeling to drive down onto the flat and find life going on as normal. For us the feeling was very much as if we were still in lockdown. On the Monday evening, I went to choir rehearsal in Ferntree Gully, blinking in the unaccustomed bright lights. Many of us Hills residents had brought items to be recharged during the evening. At end of the night we drove back up into the darkened Hills.

At home, we went into camping mode. There was no hot water, but we had plenty of fire wood, and our very effective wood heater. We cooked with gas and our little portable gas fridge kept our essentials cold. I took to having my bucket bath in the afternoon, when it wasn’t quite so cold in the bathroom. It was ten days before our power came back on, on June 20th.

The reprieve from lockdown lasted only a month. By July 16, Melbourne was back into working from home, home schooling, and leaving home only for essential purposes.

Women's Work

Like women throughout history, most of the women in our family have had the primary job of parent and homemaker. Those homes range from simple pioneer cottages to majestic residences with grand staircases and sweeping verandahs. Nearly all of those women have also done paid work. And some of those who have not been specifically employed, have had supporting roles in their husband’s careers. Some jobs have been done by different family members across different generations.

None of our women have had traditional men’s careers, but, across the generations, we have covered a wide range:

AGRICULTURE (Dairy maid, Famers’ wives)

HEALTHWORK (Doctors’ wives, Aide, Occupational Therapy Assistant)

HOSPITALITY/TOURISM (Publican, Office Administraion, Horse Trail Guide)

RELIGIOUS SERVICE (Lay Preaching and other good works, Nun)

ADMINISTRATION (Postmistress, Sales Administration Supervisor, Office Administrator)

THE ARTS/CRAFT/DRAFTING (Whitework, Semco and Dressmaking, Drafting and Drawing Office, Drafting, Drawing and Card production, Art and Craft Activities for At Risk Children, Set Design and Construction, An Artist in the Hills)

RETAIL (Grocer, Checkout Chick)

SCIENCE (Laboratory Work)

EDUCATION (Teacher)

AGRICULTURE

Dairy Maid

Our paternal great, great grandmother, Catherine Bourke, née Kelly, worked as a dairy maid in Limerick before marrying Michael Bourke, and emigrating to Australia, in 1839. When they arrived in Melbourne, their first job was managing a dairy farm in Moonee Ponds. Catherine’s knowledge and skills no doubt influenced this decision.

The “famers’ wives”

A recent (2022) Guardian article tells us that, until 1994, women could not list “farmer” as their occupation on the census form. Instead they were viewed as “non-productive silent partners”. Even today, when 49% of real farm income is contributed by women, our image of an Australian farmer is almost entirely male. This puts “farmers’ wife” in this exploration in a particular light.

Another interesting aspect of these women from our family history is the divide between the wealthy squatters and the ordinary people of the land.

Martha Rye, the “poor little thing”, whose story we told in the June 2016 post, was a “farmer’s wife”, as was her mother, Elizabeth. Both of these women had very large families.

Elizabeth, our great great great grandmother, had eleven children. We can work out quite a bit about Elizabeth from a newspaper story, written about her husband, Adam’s life. She had worked in service, as a housekeeper, before she and Adam emigrated to Australia, in 1848. She could read, but not write.

They grew potatoes and onions, first on a rented farm near Geelong, then on two acres in Broadmeadows. The whole family would have been involved in the farm work, especially at harvest and market times.

We know that Adam not only worked as a labourer on neighbouring farms, but also spent time away trying his luck on the goldfields. It would have fallen on Elizabeth and the children to keep things going on the farm.

Martha, Elizabeth’s daughter, was married to Joachim. They would have had long days on the dairy farm, Heather Farm, near Kilmore. We learned a bit about her from her daughter Sarah, born in 1866. We wrote about this in August 2016. Sarah wrote with sentimental nostalgia about milking the cows, Blossom, Peggy and Strawberry; feeding poddy calves; working the separator; and rearing seventeen children. But between the lines, one can see the massive workload.

Around the same time, our paternal great great grandparents, John and Johanna McCormack, bought their 15,000 acre grazing property, Balham Hill, fifty kilometres to the west. So, in a sense, Johanna was also a “farmer’s wife”. But what a different life! John, a Justice of the Peace, and community leader, had staff to attend to the farm. Their four surviving children all went to boarding school in the city, for their secondary education.

John’s father, also called John McCormack had also been a wealthy grazier. His wife, Grace, lived there at the property “Landscape”, at Tallarook, until her death aged 83. I doubt she would have thought of herself as a “farmer’s wife”.

Two generations on, Johanna’s granddaughter, our Auntie Tish, also married a farmer, near Warrnambool. Matt Rae was probably more of a hands on farmer than John McCormick, but he, too, was considered a grazier, and Tish’s life did not run to milking cows and feeding poddy calves.

Around 1950, close to the time Tish became a “farmer’s wife”, our mother’s aunt, Beat, and her husband Bill, sold their Surrey Hills grocery and bought land for a dairy farm in Cockatoo. The activities on this farm were similar to those at Heather Farm, a hundred years earlier: milking, feeding calves, working the separator. The difference in their lives is technological. An electric milking machine and separator, tractors, hay bailers, meant that they ran a dozen cows instead of three. And they had three grown children instead of seventeen. Nevertheless, they all had to work hard to make the farm pay enough to support them all. We wrote in detail, in our November 2017 post, about our childhood visits to this farm. There we described Beat’s pigs. This was her major farming contribution. She was not just a “farmer’s wife”, but actively involved in the decision making and physical work of the farm.

Auntie Beat

HEALTHWORK

Health work does not feature much among the women in our family. there are no doctors or nurses, that we know of.

Doctors’ wives

Our grandmother, Grace, and her daughter, Joan, were “Doctor’s Wives”. Wealthy, well connected, pillars of society, these women had no real job. In both cases, their husband’s surgery was within their house, but they were not required to deal with actual patients.

Among the women in our family, there are a few cases of unskilled health work.

Aide

Like so many women, our mother, Alice, “went back to work” when her youngest child was about ten years old, in 1966.

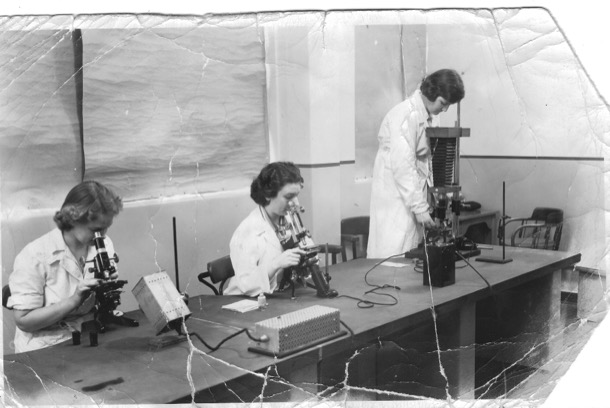

The only job she had had, since leaving school aged seventeen, was the wartime munitions work she had done at Maribynong, which today would have been called Lab Technician.

What skills did she have to draw on, apart from housework and parenting?

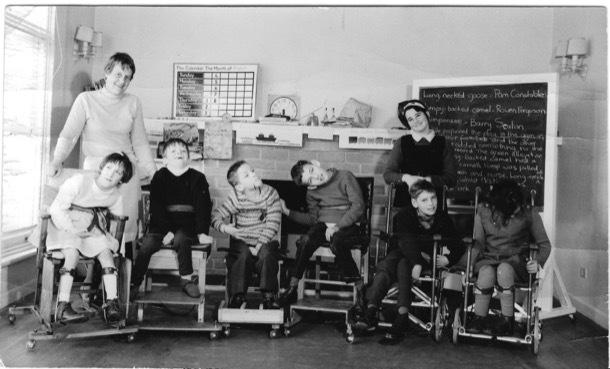

So her job as an “aide” at Lady Herring Spastic Centre was a low paid, unskilled one. She was assigned, with one other carer, to a “class” of Cerebral Palsied kids roughly the same age, none of whom had the ability to speak, and many of whom could not feed themselves. This was before the days of Communication Boards, so even the most able kids could not communicate much.

I, too, had a job at Lady Herring, after I finished school, and before I began the university year.

The centre was in Malvern, and Alice, and I, for the few weeks I was there, travelled by tram, along a very familiar route, down Riversdale Road.

There were a few qualified staff at the centre, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, but the program, such as it was, seemed to be up to people like Alice to devise. With the exception of the bus drivers, the whole staff, including the boss, was female.

The kids commuted on a special bus, and spent the whole day at the centre. Much of the time was filled with dealing with their physical needs, but there were excursions, shopping trips, walks around the neighbourhood, music sessions, and a memorable overnight “camp”. Although low status and poorly paid, it was stimulating, challenging work.

Alice with her "class"

Occupational Therapy Assistant

On the strength of my experience at Lady Herring, I did two other holiday stints as an OT assistant.

I worked with our OT friend Rikki, at Fairfield Infectious Diseases hospital for a little while. This was before HIV made it such an important place. My memories of Fairfield include the beautiful historic buildings; dozens of beds in a row, in the children’s Hepatitis ward; and the iron lung ward: people who had contracted polio as children and spent their life lying inside huge metal chambers that helped them breathe.

My job was mostly helping tidy up the activity room, and working in the ward with the Hepatitis kids: mostly bringing them things to do.

Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital

And then, during another long uni holiday, I worked at Montefiore (Jewish) Aged Care in St Kilda. It was perhaps 1970. Most of the Occupational Therapy “workers” there were volunteers: generally well off middle aged Jewish women doing their bit.One of those volunteers, who I remembered just as Mrs Hayman, later became Sue’s mother in law.

In my memory, the whole staff, except the doctors, were women.

In our centre, where the patients came to us, we ran activities like singalongs, bingo, games etc.

Many of our patients were post war immigrants from Europe, and some had been in Nazi concentration camps. It was the year that Melbourne emergency vehicles changed from sirens to “nee naw nee naw”, the same sound the SS vehicles had used in wartime Europe. When we heard the distant sounds approaching along St Kilda Road, we needed to be aware of some patients’ reaction.

I remember being told that that gentleman with his trousers barely held up with string, had been one of Melbourne’s top barristers. I still have the book called “Favourite Jewish Songs”, piano accompaniments I used for the singalongs I accompanied.

HOSPITALITY/TOURISM

Publican

Catherine Bourke, in her new home near Pakenham from 1844, helped with the establishment of Minton’s Creek Run, the farm in the Toomuc Valley, that they bought with another family. But in 1850, they bought the Latrobe Inn, on the main Gippsland Road, in current day Pakenham. Catherine moved out of the slab hut up the Valley, with her seven children, and became a publican. The inn became known as Bourke’s Hotel. Michael was still very involved with the family, and they had another eight children, but it was Catherine who ran the hotel.

As well as a stopping place for travellers, Bourke’s hotel was the local post office, and a hub for the community.

Catherine Bourke

Horse Trail Guide

Catherine’s great, great, great, great, great niece Eliza, one hundred and seventy years later, also moved to the country to start a new job in tourism. Seeking a change from office work, Eliza moved to Mansfield to work for Hidden Trails by Horseback. This company runs trails in the Victorian High Country and also at El Questro Station in the Kimberly.

In Eliza’s own words her job entailed the following:

Up at the crack of dawn. Run the horses in. Feed the ones we are working that day. Brush and saddle the horses needed for the rides.

Determine the guests riding experience, match to a horse. Sign indemnity forms, Go through basics (stop start turn etc) and then lead the ride out, float in the middle of a big group, or tail the group at the back.

We go out on four rides a day:

*AM 2 hour ride (around the station)

*Kids intro ride (around the paddock)

*1 hour loop (around a different part of the station which includes the deep moonshine creek crossing)

*PM 2 hour ride (incorporation of the 1 hour loop with a look out stop where we would take a pack horse with drinks and nibbles and tie the horses up and have a sit down)

In between those rides we feed lunch to the horses working. Then back to the stables in the afternoon, Unsaddle, wash down and tip out the horses. And then do it all again the next day. Shuffling them around in different paddocks so we could keep them all in work.

There was 40 horses total.

Long days. Great experience.

Eliza at El Questro

RELIGIOUS SERVICE

Lay Preaching and other good works

Both our mother Alice and her maternal grandmother Emma Coates (née Dau) were staunch protestants and indulged in a little lay preaching and good works.

Emma Dau, one of seventeen children, was married to Alfred Coates, who was a Wesleyan Methodist Pastor. Emma’s married life consisted of raising a family, and her duties as the Pastor’s wife. Family stories tell of her devotion to these duties and of her riding around the parish on a push bike.

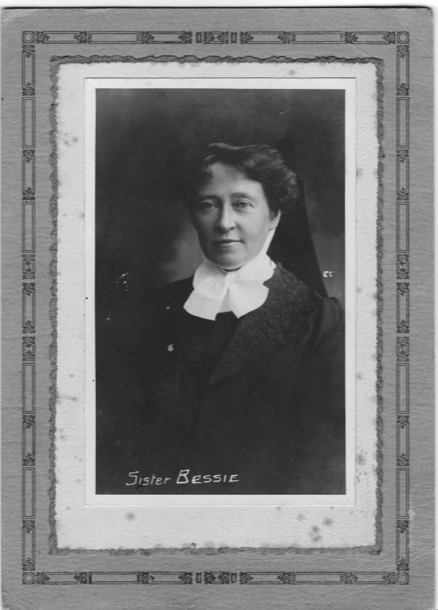

At some stage in her life, when our mother was still a child, Emma also became a Home Mission Sister and was known as Sister Bessie. As a Home Mission Sister, Emma wore an impressive uniform, that is described vividly by our mother and Auntie Marge, who as children were very impressed by this formidable woman. Here they are discussing her:

Sister Bessie

Sister Bessie worked at the Methodist Home Mission in Brunswick Street Fitzroy, in the 1920s and 30s. Sister Bessie’s work with the ‘fallen women’ and the poor, in the slums of Fitzroy was also vividly remembered by Marge and Alice. Sister Bessie’s good works involved anything from delivering babies to rescuing unmarried mothers. All of this was carried out ‘in the slums’ and in ‘poor, dirty houses’. One story has it that Sister Bessie once took off her own petticoat to give to a poor woman who did not have enough clothing.

The slums of Fitzroy were indeed slums, with a reputation for dirt, filth, disease and crime, a fearsome place. Streets were unpaved, there was no running water in many of the crowded and small weatherboard houses and children often ran barefoot.

So bad were the Fitzroy slums, that in the 1950’s they were demolished and the population was moved to the Housing Commission Towers, still standing in Brunswick Street.

Slums in Melbourne

Sister Bessie also travelled within Victoria and Tasmania. She was lay preaching, called ‘deputation work’ and raising money for the Home Mission. Apparently she was a very good story teller and must have not only impressed her young grand daughters but also her audiences, as she regaled them with stories from ‘the slums’. So impressed was one small child, that she gave up her doll ,to be given to the poor children who had no toys.

Half a century later Alice stood in her grandmother’s shoes at the same pulpit of a small, now Uniting Church, at Jung in the Wimmera.

Alice was also doing ‘deputation work’ in a fashion, preaching about world poverty and inequality. She was also raising money for the Uniting Church’s fight against poverty. Alice mentioned that her grandmother, Sister Bessie, may also have preached here. Incredibly a member of the congregation remembered as a small child listening to Sister Bessie preaching and telling stories. She said,“She was a wonderful story teller.”

Jung Methodist Church

The Nun

We grew up with stories of a nun in the family but knew no details. With the assistance of Google, we now know that Frances Bourke, [1883-1964] Jim’s Great Aunt, joined the Presentation Sisters, probably as a young woman, and became Sister Magdalen.

Presentation Convent was founded in Windsor in 1873 ,after a request by the Parish Priest for sorely needed teaching staff at St Mary’s school.

We are intrigued about Sister Magdalen and her role. Was she a teaching Sister or did she have another role at the Windsor Convent? Did she spend her life in the Order? Watch this space, hopefully more to come.

Presentation Sisters

ADMINISTRATION

Administration is part of many jobs, often the least pleasant part; writing reports, managing co workers, attending meetings, communication, ordering supplies, keeping records. These tasks are familiar to many workers.

Postmistress

In 1859 Bourke’s Hotel in Pakenham also became the community post office, ten years after Michael had bought the license. He became the founding post master of Pakenham. After his death, in 1877, Catherine became the Pakenham postmistress.

Up until 1901, each of the colonies operated their own postal service. After Federation, they all merged to become the Postmaster Generals Department (PMG).

Cecelia,(Cissy), Catherine’s youngest child, who never married, continued the role after Catherine’s death in 1910.

The job of postmistress would have involved taking sacks of mail to and from the Cobb and Co coach, later the train, and sorting it for people, who would come in to collect their mail.

Over time, the job of post mistress also included a savings’ bank, money order office and telegraph station; quite an important role in the local community.

Sales Administration Supervisor

But for a proper administration job, Tessa is our woman. Her job at Kenworth Trucks is to project manage the outfitting of each truck. She manages a team of people who put 22 trucks per day together, to the specifications of each customer. Keeping all the balls in the air, making sure everyone is gainfully employed, smoothing relationships with customers and between workers, maintaining records, supervising departments. It’s a very large and stressful job.

Office Administrator

Another organised young woman is Eliza who has also worked in office administration, at Nautilus Training and Curriculum, the company founded by her dad, Ian.

THE ARTS/CRAFT/DRAFTING

Whitework, Semco and Dressmaking

Three of our women worked in the textile industry, a generation apart. Both Great Aunts Bert and Beat and our Auntie Marge were involved in the embellishment of textiles with embroidery, and in dressmaking.

In our post on Auntie Bert, ‘A Sterling Character’, in March 2019 we explored ‘Whitework’. Whitework embroidery is the general term for hand embroidery worked with white thread on white fabric. It was used on many household items from babies’ bibs and tea towels to under clothes. Bert and Beat who, as young women, worked in this industry, probably worked in Flinders Lane. At this time it was the centre of the “rag trade”.

Auntie Bert, being unmarried, needed to continue in the workforce, but also be available to help her elderly parents with whom she lived. A talented and resourceful woman, she started a dressmaking business, working from home. Although self taught, her reputation for fine tailoring and expertly fitted ladies’ wear soon spread amongst the ladies of Camberwell and Surrey Hills. As her clientele increased and business grew, she had to move to bigger premises, and Bert leased space for a workroom and office in Riversdale Road Camberwell. This business is also described in our post ‘ A Sterling Character”

Drafting and Drawing Office

Our Auntie Marge worked in a number of drafting and drawing offices during her working life. After her short stint teaching, Marge began work in a drawing office in Collins Street, and then, during the war, moved to the drawing office at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory where Alice also worked. In 1941 Marge moved again, this time to the drawing office at ICI.

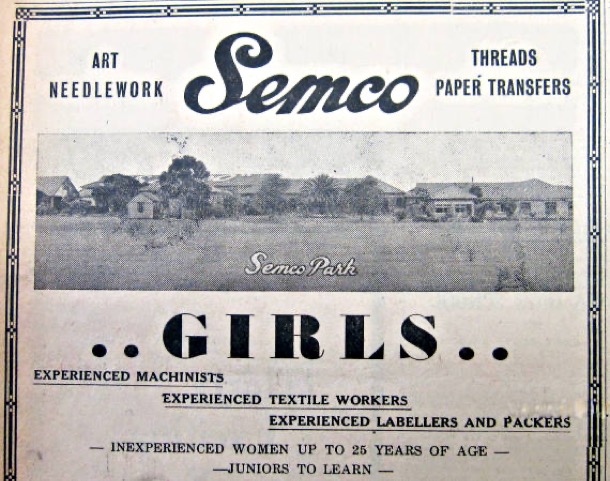

Later in life, Marge used her artistic talents at Semco, designing patterns for embroidery transfers. The designs were created as line drawings and printed onto tissue paper transfers, to be sold to women to embroider for items for the home, or as gifts. The transfers were ironed onto cloth after which the item could be embroidered accurately following the design. Margaret and I can remember embarking on an Semco embroidery project that I don’t think we finished.

Semco Workroom

Typical Semco Embroidery

Designs subjects were flowers and animals, both European and Australian, cute houses, toys and even landscape scenes. Amongst the many items destined for embroidery were doilies, tablecloths and serviettes, tray cloths ,handkerchiefs, babies’ outfits and children’s clothing.

Margaret and I can also remember visiting Auntie Marge at Black Rock and seeing her designs on a big drawing board. A working mother was a novelty for us, as our mother did not work outside the home.

The Semco factory and workshops located in Semco Park, Black Rock, was quite a progressive company and treated its employees well. They paid award wages to women, and provided recreation facilities for the staff, including six and a half acres of garden and lawn for their enjoyment. It was a large employer, as not only were the designs created and printed, but the embroidery cottons were also spun and dyed.

Marge worked for Semco as a part time employee, and at the same time studied Interior Design at RMIT. Both were unusual. For many women of her era, part time work outside the home was difficult to find, even once children were at school. Marge was fortunate to have Semco in her area and for it to be accessible on public transport. This allowed her to work there for many years, while pursuing her life long interest in further study.

Drafting, Drawing and Card production

Marge worked in a number of drafting and drawing offices during her working life. After her short stint teaching, Marge began work in a drawing office in Collins Street and then, during the war, moved to the drawing office at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory where Alice also worked. In 1941 Marge moved again, this time to the drawing office at ICI.

In between jobs outside the home Marge, like her Aunt Bert, started a business from home. Using her artistic skills and her design experience at Semco, Marge launched a greeting card business. She designed and screen printed the cards, packaged them and sold them to shops specialising in handmade original work.

Art and Craft Activities for At Risk Children

From this heading, it is obvious that this position could be fraught with difficulties. As a nineteen year old I was blissfully unaware of the worlds these children came from. Orana was a Uniting Church children’s home for at risk children and ‘orphans’. I remember mostly a group of cardigan and jumper clad children in skirts and shorts, traipsing into a linoleum floored space to participate in whatever I decided to do. I don’t remember anyone checking the activities, or that I had to run them past any of the staff. Some of the activities were very, very messy, but the children willingly helped me clean up. The confronting and difficult part of this job was not the behaviour of the children, but the heavy prevailing air of sadness in that place.

Set Design and Construction

Lois learnt woodworking from her dad. Together with her design and craft skills, she developed her “Top Props” business, designing and creating stage props. For instance, Deirdre’s Tappers’ concerts would not have been the amazing spectacle they were, without Lois’s colourful props.

An Artist in the Hills

Through her meticulous fine drawings and paintings Katherine explores a fantasy world inhabited by little creatures and characters, who are at home with spiderwebs and toadstools or nestled under gnarled old trees . Working from her house and studio in the Dandenongs, she is pursuing her interest in children’s book illustration.

RETAIL

Grocer

Our Great Aunt, our grandmother’s sister, Beatrice Morris (nee: Holm) owned a grocer’s shop in Maling Road, Canterbury, for a number of years. Bill Morris had previously worked at Lawson’s Grocer in Middle Camberwell , so having experience, this was a logical move. We are not sure how long they were in Maling Road but presumably Auntie Beat helped in the shop as well as raising a family of three boys. It must have been reasonably profitable, as during this time they built a house in Balwyn, and then sold the business to buy the farm, Sefton Park.

“Checkout Chick”

Anna, Beatrice’s great, great niece, is the only other woman in the family who has worked in retail, and this too was in grocery shop: the Renaissance Supermarket, Hawthorn, in the 1990’s: it was a supermarket of course. At sixteen Anna was keen to have a part time job and earn her own money. Her position was ‘checkout chick’, working on the register, before scanning of prices using barcodes was all entirely automatic. For instance, the checkout chicks had to memorise the PLU code for all the individual fruit and vegetable items, and this had to be entered on the register, manually.

SCIENCE

Laboratory Work

After the horrific use of chemical warfare (gas), on the European battlefields during the 1914-18 war, many countries began to work on ways to protect their populations from gas warfare.

Australia began its own “Chemical Defence” research program in 1926 at the Munitions Supply Laboratories, in conjunction with Melbourne Uni. They developed and assembled “respirators”.

By the time the second world war began in 1939, scientists were well advanced in this work. In 1940, over half a million respirators were manufactured at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory, and more than 500 people were employed there.

Our mother, Alice worked there, in the microscope section, testing the penetration of gas that came through the filters. When she would describe this work, she would indicate tapping and counting as she stared down the microscope. She had studied Year 11 Chemistry the year before she started.

Alice, left, working at Maribrynong

EDUCATION

Teachers

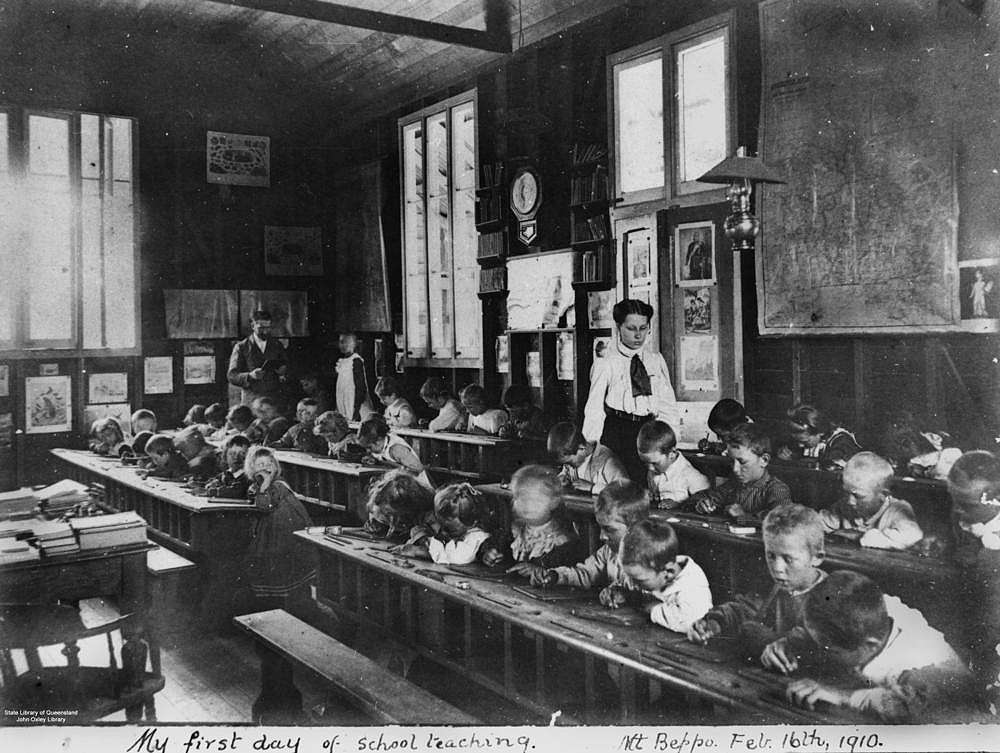

At least five of the women, in four generations of our family, have been teachers, some primary, some secondary.

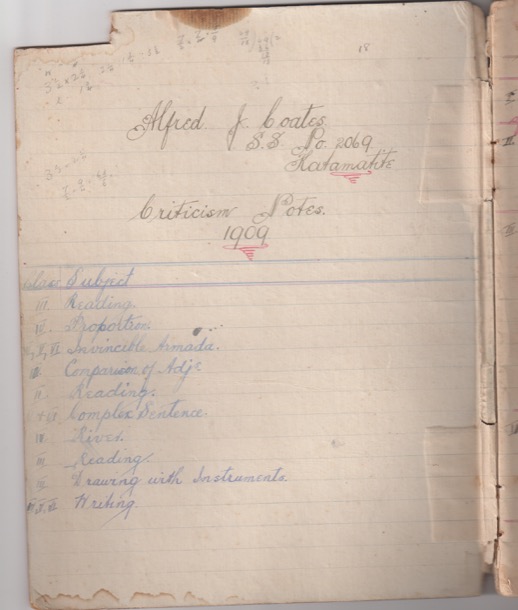

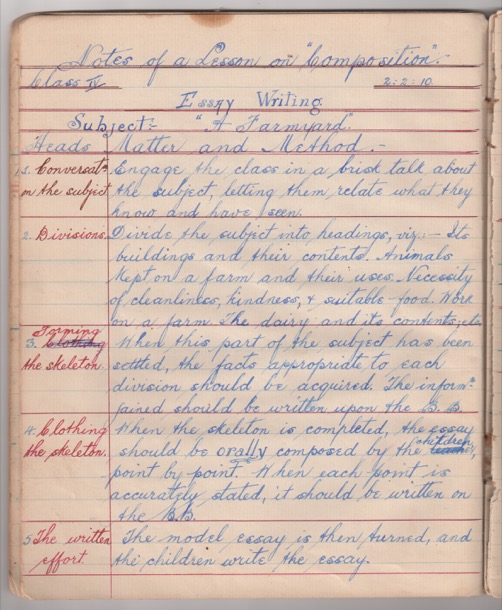

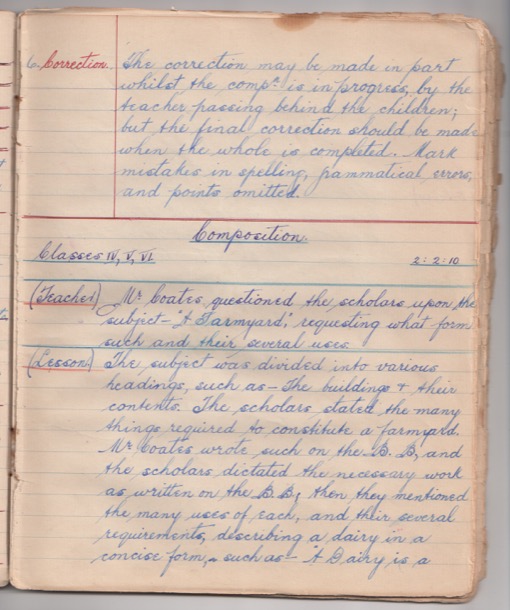

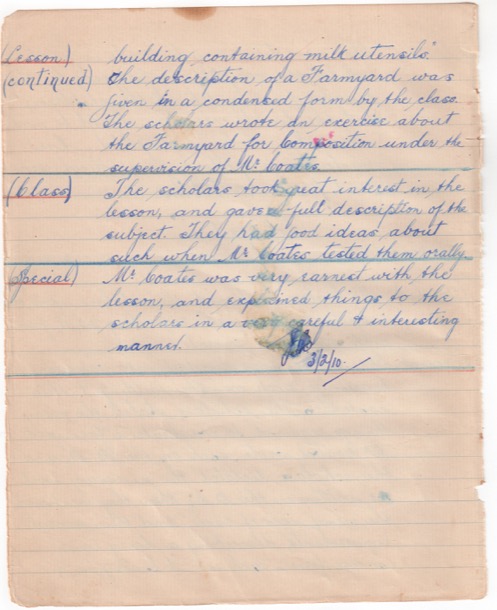

The earliest we know of is our Nana, Alfreda, who taught primary school, before marrying Alfred in 1916.

She had fought for a chance to continue her education after secondary school. There was not enough money for university, and so she went to Melbourne Continuation School, which later became Melbourne High School. Its focus was teacher training and thus, after two years, Alfreda became a teacher. Presumably she taught for about four years. Women had to resign from teaching when they married.

Our Auntie Marge, Alfreda’s eldest daughter worked as a teacher for a year, straight from school. She taught 50 five year olds at Balwyn North, as a “junior teacher’. She also went to RMIT three nights a week dong Fine Art, her real passion. She only lasted one year, having decided that she was not suited to teaching. Our mother, Alice, while not actually teaching, worked as a school librarian assistant for the last years leading up to her retirement.

The next generation is ours, and at least four of us worked as secondary teachers: Pauline for a few years, and Sue, Anne and I until our retirements. All three of us did our initial tertiary education, including teacher training, on “Studentships”, which provided free education and a small wage, in return for three years service, usually in the country. Sue went to Sale, Pauline to Portland, and Margaret to Moe. Sue and and I wrote about our first year teaching experiences in a post on October 28, 2015, filed under “Young Adults 1970s”

Sale High School

Of our own daughters and nieces, only Anna has taken on the mantle of teaching. She even completed most of a PHD in Education. Recently, in her mid forties, she has gone back to the English classroom in a secondary school, where she is thriving!

Such a lot of different job experiences, and yet, within relatively narrow parameters. No astronauts, truck drivers or plumbers.

And, it must be stressed, the most important job for almost all these women, over six generations and nearly a century, is that of parent and homemaker.

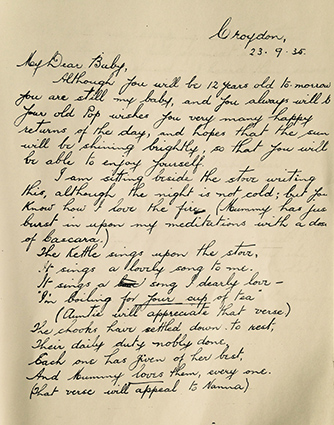

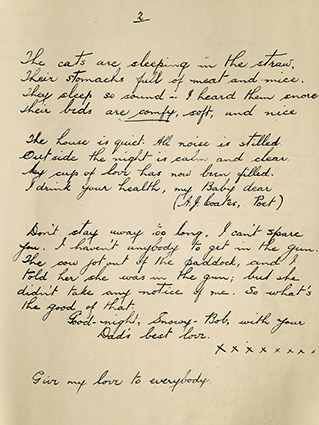

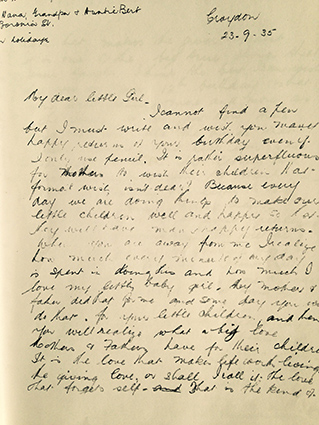

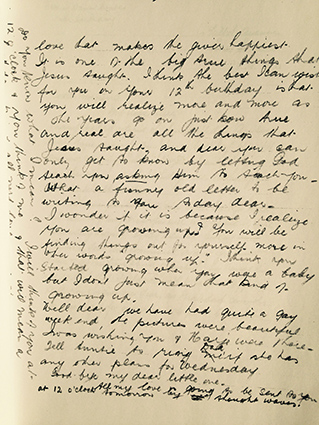

The Croydon Years

When the Coates family moved to Croydon it was the beginning of the Great Depression and many men were out of work. To complicate matters, Alf had been in partnership in a hardware business in Bacchus Marsh that had burnt down. Not only was the fire a personally traumatic experience for the family, as their house had also burnt down, but the business was not insured. As manager, Alf was responsible for the lack of insurance. He was therefore "lucky indeed" to have the job as the hardware store manager at the Croydon Timber Yard. He was on a reduced salary as recompense for the losses of the other Bacchus Marsh partners, who now owned the Croydon business.

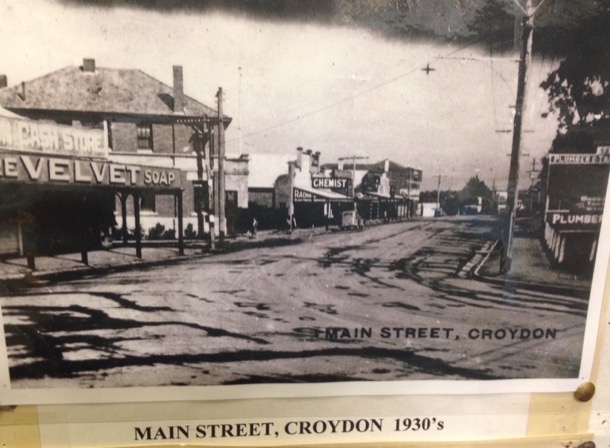

Croydon was at that time a pretty, country town, connected to the world by the railway that ran, as it does now, from Flinders Street to Lilydale.

White settlement had reached Croydon in the 1850’s, as timber cutters arrived seeking new sources of timber for the needs of rapidly expanding Melbourne. Many small, and a few large land holdings were taken up, and fruit trees were found to flourish in the area.

The town that the Coates family found, spread out from the railway station. Businesses and shops were strung out along the long, wide, slightly curving main street. The Dandenong Ranges made a lovely backdrop to the town that was surrounded by small farms, orchards and bushland. Home for the Coates was a small house, painted battleship grey, in Hewish Road, very near the corner of Main Street. This was the wrong side of the tracks. The expensive houses were built over the railway line in Wicklow Avenue, extending up the hill towards what is now Maroondah Highway.

They remember their house as having a beautiful backyard, graced by an enormous Mulberry tree and a large vegetable garden. There was a cow paddock on one side of the house and the Wine Hall on the other. Hewish Road at that time was unmade, covered in hard stone embedded in the clay. The Coates were right in the business end of town: Cook’s Grain Store was directly opposite and Croydon Timber Yard, not far away, also in Hewish Road. Not only did this fiercely teetotal family live next to the Wine Hall located on Main Street corner, but on the other corner was the Croydon Hotel. These two establishments loom large in their childhood memories, as they were the source of the moaning drunken men that they sometimes heard outside. Occasionally their father had to take the men home.

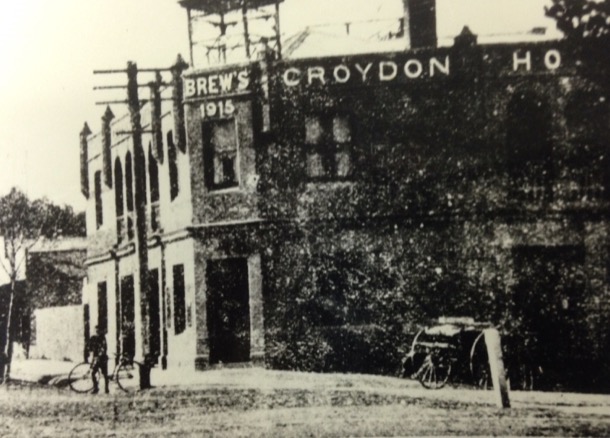

Croydon Hotel:

Croydon Wine Hall:

Alf worked weekdays, Friday nights and Saturday mornings at the timber yard. Once a month he also drove the truck to the wharves to collect timber.

Money was tight, especially as Alf and Alfreda wanted their girls to have a decent secondary education at MacRobertson Girls' High School in Albert Park. One-third of Alf’s wage went on rent and by the time bills were paid and weekly expenses were covered, there was not much left over. At secondary school, fees were charged, books and uniforms would need to be purchased and weekly train fares paid for. Daily life therefore included the care of livestock and the processing of milk and eggs: all quite time consuming.

As well as their home grown vegetables and fresh eggs, the Coates family produced their own milk and cream.

All was not hard work however, and the Coates’ kitchen, warmed by the one-fire stove, was the venue for cups of tea and chats, many of them about cricket. In the picture, Alf is second from the top left:

Marge and Alice had a very happy childhood in Croydon. They played often with the Cook sisters, Yvonne and Margaret, who lived opposite. The Cooks had once owned the Croydon Timber Company, Alf’s employer.

Their house was on the other side of Hewish Road, next to the hotel. Connected to the Cook’s house was the grain store, which was now the core of Mr Cook’s business. There were delivery horses in a nearby stable too, and cows in the paddocks behind. The grain store was packed with bags of chaff and grain. The girls spent many hours playing in there, climbing right up to the roof.

One happy memory is of “penny concerts”. Hours of preparation: planning, costume making, and rehearsing, culminated in a concert performed on the Cook’s wide side verandah. This seemed to be mostly in the summer holidays, when the Cook girls’ cousins came to stay. Marge and Alice sang part songs, often Elizabethan madrigals they had learnt at school: Alice singing soprano and Marge, alto. The adult audience (probably only their parents) paid a penny to attend.

Alice remembered playing a sort of scavenger hunt, following written clues to find a prize. “Next clue under the camellia bush”.

She also remembered marbles, played in the dirt on the side of the unmade Hewish Road. When Sue and I stood on the same spot in our Croydon visit, we could hardly cross Hewish Road, for traffic! In the 1930s, it was a quiet gravel road with no gutters and unmade footpaths.

The Coates and Cooks lived opposite each other, and used to signal out of windows at night across Hewish Road. They planned, but never carried out, midnight feasts.

The wild games and excitement of playing with the Cook contrasted with the much more demure and restrained Hebbard girls. Pam and Honor Hebbard were the daughters of Frank Hebbard, the Primary School Principal, and friend of Alf and Freda. Their huge library of books were available for Marge and Alice to borrow, and the garden was a delight to play in. The Hebbards lived up on the Hill, at the top of Kent Avenue, which wound up to what is now the Maroondah Highway, through foothills bushland. A favourite activity with the Hebbards was to wander this bushland looking for native orchids. The remnants of this forest are much prized today, though much of it is degraded, and many of the species of orchid are now only to be seem in a museum.

Visits to the beach, during Marge and Alice’s Croydon years, were limited to School and Sunday School picnics. But they did learn to swim. They would go by train to Lilydale, where there was a huge concrete tank, right on the side of the Olinda Creek. Fresh water would flow in and out with this quite large perennial creek. Alice remembered Mr Hebbard lining them all up along the side and getting them to enter the water with a shallow dive. Nowadays the pool has become a more modern outdoor pool, but it’s still in much the same place.

Friday night shopping was another form of fun. Marge recalled it as a chance for everyone to parade up and down the street. Alice remembered buying “sixpennorth” of lollies and sharing them out. It was a simple life for these country kids. It is notable that, three years apart in age, much of their leisure time was spent playing together.

Marge and Alice of course went to Primary School during these years at Croydon, Marge as far as Grade 8. We will spend more time on this important topic at a later date. Suffice to say, at the moment, that their parents’ friend, Frank Hebbard was the Principal, and he ran a very enlightened, rich educational program, in which the girls flourished. The Croydon Primary School has new premises these days, but the old buildings are still there, now occupied by a Community School.

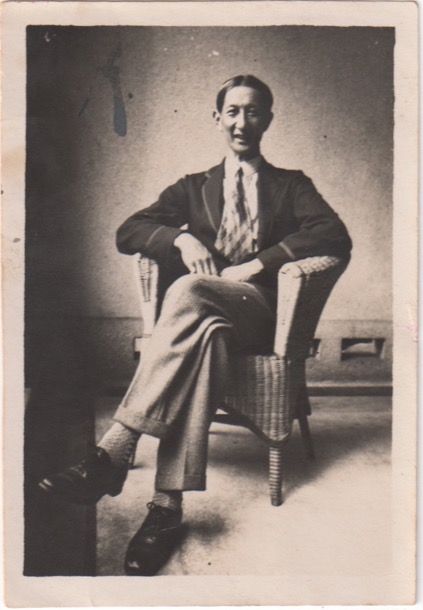

Family entertainment included hikes from Croydon to Kalorama, and visits to friends, the Cheongs. They were a wealthy and prominent family in the area. At our visit to the museum in Croydon we found many mentions of them, in particular their importance to conservation of remnant foothills vegetation. Even now Cheong Wildflower Reserve, near Croydon, still fulfils that role.

Mr Cheong, from our mother's photo collection:

In their leisure time, many happy hours were spent in the Coates’ warm kitchen, “yarning’.

Even though much of the good food the Coates family ate was home grown, some things had to be purchased at the Main Street shops.

The Croydon years were remembered very fondly by both Marge and Alice. They were formative years for both of them. Alice actually names the four areas of interest from those years that became her life long passions.

In 1936 the Croydon years came to an end with the death of Martha Holm, Alfreda’s mother. Presumably the family had to move back to Boronia Street, Surrey Hills to help Alfreda's sister, Berta take care of Roger Holm, now quite an elderly man. Berta was working full time at her dressmaking business. Alf found a new job in the city and Alice embarked on her secondary schooling at MacRobertson Girls’ High School.

Decade by Decade

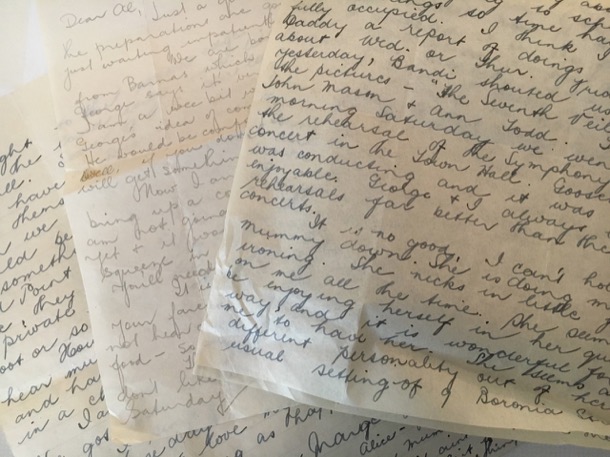

Here is the audio of this from the recordings:

With our more modern education, we have less of a firm grasp of History, and we know that our children, and their children have, and will have, an even sparser knowledge. So we have taken the overview concept, explained a little more fully, and added in our father’s family history and other aspects we have recently discovered.

Alice and Marge finished recounting their family stories at 1950. One of our tasks in this project has been to continue on from then, and so we have done just that. We explore the nineteen fifties, sixties and seventies, linking what was happening in the wider world into our own lives.

1850-1950

Between 1839 and 1872 our ancestors arrived in Australia.They came from both Northern and Southern Ireland, England, Germany and Denmark. All were from humble origins, having worked as agricultural labourers, domestic servants, a baker and an engineer. Some were already married and others met here.

As our ancestors built their new lives in Victoria, the First Australians had already felt the disastrous impact of European contact. There had been violent conflict, the Wurundjeri population had been decimated and the survivors relocated to reserves or camps a ‘suitable' distance away from the growing population of Melbourne and outlying settlements. In 1844, when the Bourkes took up their selection at Pakenham, they were the first white settlers in the area and the “blacks camp” by the river was noted in Catherine’s memoir. Several years later, Adam Rye, from the other side of the family, was robbed by a party of ’50 blacks’. The newspaper report notes that ‘the blacks at this time were very treacherous’.

With the discovery of gold, in New South Wales and Victoria, there was a huge increase in population and in wealth.

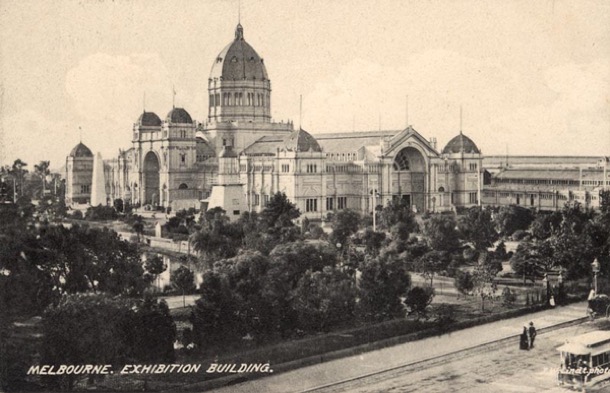

Victoria benefitted the most. Melbourne became Australia’s largest city, with a huge land boom. Grand old buildings like the Melbourne town hall and exhibition buildings are reminders of those glory days.

The increase in population, rapid development and the attraction of the goldfields led to a shortage of workers. This meant great job opportunities at every level. It also put workers in a good bargaining position.Trade Unions developed and working conditions were the best in the world. Australia was an egalitarian workers’ paradise.

Small businessmen, like publicans, bakers and lawyers, prospered with the growth in Melbourne. For farmers, it meant bigger markets, more mouths to feed. The growth in country towns, better roads and railway development made life in the country less difficult.

Engineers had a lot of work with the sudden development of infrastructure and property developers were run off their feet. Our grandfather’s grandfather, a young engineer from England, was building bridges in the expanding colony. While building the bridge across the Barwon River, his son, our grandfather’s father, was born, his birth unregistered.

Back in ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ our grandmother’s grandparents who had arrived from Belfast, were developing St Kilda: building large houses and public buildings for those who were prospering in the boom town.

On the land, our maternal ancestor Adam Rye, who had survived the attack by ’50 blacks’, settled in Geelong and worked as a farm labourer. He was later gripped by gold fever and went north to seek his fortune, only to be held up by bushrangers and lose his meagre pickings. His daughter married a German immigrant, Dau, and they settled on a mixed farm at Wandong. Here they raised seventeen children and supplied food to the growing population.

Meanwhile our paternal forbears, also on the land, were making their mark in Gippsland and North Central Victoria. In Pakenham the Irish Bourkes were building their family of thirteen children, and now owned Bourke’s Hotel. They were becoming significant landowners and community members, as they set about acquiring land, marrying their daughters well and establishing their sons on large and prosperous properties. They also served their community in local Government and built the horse racing industry in Pakenham.

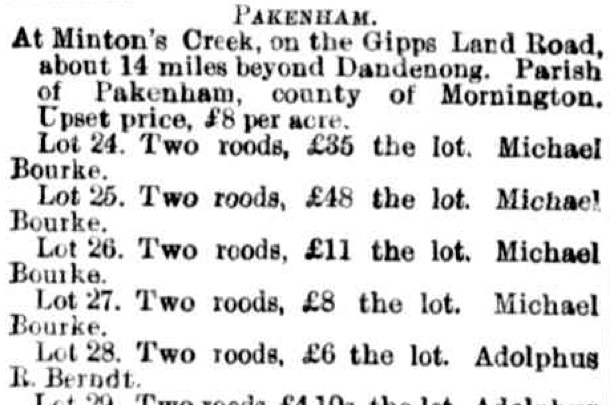

1858 Land Sales, Michael Bourke's purchases:

The MacCormacks, in North Central Victoria were also acquiring and working large grazing properties, firstly in Tallarook and then in Molesworth. They too were pillars of the local Catholic Church and community. Our grandmother was born there, at Balham Hill, pictured below.

Melbourne became the financial centre of Australia and New Zealand. The Pakenham Bourkes’ fourth son, our great grandfather, was part of this world. He had moved to Parkville and built his law career in this thriving city. Australians were growing in confidence and the young nation was showing signs of an interest in its own identity. This was the era of Henry Lawson and Banjo Patterson, who wrote about the characters of ‘the bush’. At the same time, Tom Roberts and his paintings glorified the unique Australian landscape and the men and women who toiled there. This growing sense of identity and of nationhood is reflected in the moves for independence from Great Britain. During this era of optimism and hope our grandparents were small children, and their families were well established in both country Victoria and Melbourne.

Federation was achieved in 1901, and the country celebrated:

Australia was longer a colony but an independent nation. Melbourne was the largest city in Australia at the time and the second largest city in the Empire (after London). It was fitting that the new Parliament should sit in Melbourne while Canberra was being constructed.

The decade after Federation saw Australian women join the battle for women’s suffrage. White men over 18 in Victoria had had the right to vote since 1858, but women were not granted this right until 1908. Our maternal grandmother, Alfreda, was sixteen when women were granted the right to vote. We imagine she would have approved. She had been engaged in her own battle to pursue her dream of further education; and during this decade she finished her secondary education at Melbourne’s Continuation School, the opening of which marked the beginning of state secondary education in Victoria.

This period of prosperity, optimism, and political and social change ended in the devastation of the Word War 1. We know little of the family’s war service, but three of our maternal grandfather’s uncles served in France, and one lost his life. In the highly charged patriotic atmosphere of the time, and with mounting casualty lists, the war years must have been a difficult time, especially for our grandfather who was considered unfit for service due to ill health. He was deeply upset when given a white feather. Presumably our paternal grandfather being a country doctor, was in a protected occupation.

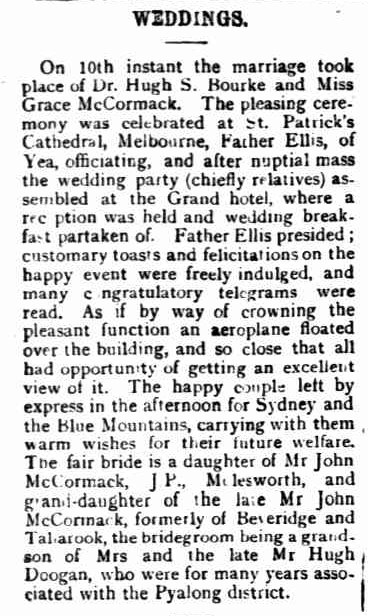

Our grandparents were all married at the end of this war. Our father’s parents were married in St Patricks Cathedral in a grand affair. Grace and Hugh then settled in Koroit in the Western District, where Hugh was the local doctor.

In contrast our mother’s parents were married in the Methodist Church in Surrey Hills in a small and simple ceremony where the bride did not even wear a wedding dress. At that time Alfreda was working as a teacher and Alf was working in a hardware shop in the city. They also moved to the country, soon after: to Eildon, where hardware supplies were needed for the construction of Eildon Weir.

Our family then lived through the Great Depression of the thirties, formative years for our parents who were by then at school. Our father was boarding at Xavier College and our mother was at Croydon Primary School. By the end of the decade the world was at war again.

During the war in a munitions factory, in Maribyrnong, two very different family histories were to merge into one. One was Irish Catholic, successful and quite wealthy, and the other was staunchly Protestant and relatively poor. One was involved in the Melbourne horse racing scene and the other was teetotal and interested in ideas and the new ‘isms’ that were emerging on the other side of the world. Our parents were married at the end of World War 2.

1950s

Our mother’s view of the 1950s, in her recording, is of a time of burgeoning economic growth and development. To us, it is the decade we first became aware of the world.

Our world was redolent with Australiana, but we were intensely aware of our British heritage, and it dominated our reading, our schooling, our whole culture. A portrait of The Queen hung in our school. Sue remembers keeping a scrap book at home of magazine articles about the Royal Family. She was particularly interested in the corgis. Apparently I had one too, and it contained very many pieces about Princess Margaret.

Enid Blyton Books:

Globally, it was a dangerous world, with the cold war in full swing, and a very real threat of nuclear war. Our parents had quite well developed political opinions, particularly our mother, so we were exposed to adult conversations about the issues of the day. Family friends and neighbours, the Lees, were active in the union movement. They encouraged our parents’ involvement in the movement for “unilateral disarmament” and other left wing activities. I remember our mother’s admiration for an older couple who took a small boat out into the Pacific Ocean to protest the nuclear testing. Bikini Atoll in the Pacific, sixty years on, is still a no go zone from the USA nuclear tests carried out there up until 1958.

This was the time of McCarthyism in America, and Australian political attempts to ban the Australian Communist Party: a divisive time, where everyday people had strong opinions one way or the other. Sue remembers Prime Minister Menzies as “the devil incarnate”.

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament became overwhelmed in the 1960s by anti Vietnam War action, but it was an important political movement of the 1950s. The familiar “Ban the Bomb”, or “Peace” symbol was invented in 1958, as a symbolic representation of ND (Nuclear Disarmament)

Our family was, by today’s standards, quite poor, but this did not impinge on our life, at this time. We were well fed, we had a stay at home mother who looked after us and the struggle to pay bills was not part of our conscious experience. As far as we children knew, we were neither poorer nor better off than our neighbours, with the exception of the family in the housing commission house nearby, whose son had polio and who didn’t always have enough to eat. The world, as we observed it in our daily life, was largely classless. Perhaps Australia at this time really was the egalitarian workers’ paradise it purported to be, to prospective migrants in Britain. (only whites of course)

Nevertheless, we knew about the religious and economic differences within our family: that our father’s relatives were wealthy and that we were not, because our parents’ union was a “mixed marriage” and very disapproved of. We were very aware of their Catholicism and our Protestantism, and that we were not as close to our grandmother as our cousins were.

Our father during the 1950s, went from working as an industrial chemist by day, and studying by night, to full time teaching. We got our first car, a television and a refrigerator. By the end of the decade there had been four children born. It was busy, but simple life, encumbered by very little “stuff”.

Our suburb of Box Hill South was the edge of suburbia, when our parents first bought their block. During the fifties the new suburbs filled in with more and more families, and the frontier stretched east towards the orchards of Blackburn.

Below is Doncaster, contrasting the 1945 view to that of today. It was little changed in the 1950s. We remember breaking an axle on our Talbot car in Doncaster, a farming and orchards area with narrow unmade roads.

The sewerage reached us during the late fifties. Neighbours got together to dig each others’ trenches. The footpaths were paved, allowing us to roller-skate along them.

The streets were deemed to be safe enough for five year old girls to walk unsupervised, from Box Hill South to Surrey Hills to Sunday School and to Bennettswood to school.

We are baby boomers, and this was the most booming time. When we began school, Sue in 1954 and me in 1957, “temporary” schools were being thrown up, and unqualified teachers recruited to deal with the rush.

My first experience of school was a few weeks in “bubs”, and then the-bursting-at-the-seams class was reduced by a handful of us being put straight into Grade 1. Here is that grade photo with Miss Meadows and her 47 pupils.

1960s

This decade covers our teenage years. It was a time of huge change in the western world. By the end of the decade, Neil Armstrong had walked on the moon, women were controlling their own fertility with the Pill and popular culture had discovered the huge Baby Boomer teens market. During the sixties, there was a general loosening and questioning of traditional social norms. Older people were probably more aware of these momentous changes. For us the loosening of the cultural apron strings, that is such a feature of these times, coincided with the loosening of our familial apron strings.

The conflict between our generation’s straining at the bit and society’s entrenched traditional values played out in our school life. As fashion hemlines rose, school uniform strictures fought them. We knelt to have the gap between our uniforms and the floor measured precisely, and hastily pulled down our hoiked up dresses whenever a teacher came in sight. The anti war slogans on our pencil cases, alongside the names of pop groups we fancied, had to be kept hidden, or there would be detention. A new rule dividing the grassed hill area into a boys’ side and a girls’ side transformed the hill into a vast empty space with a cramped central area where everybody sat alongside the invisible line. In our school, as far as we can remember, there were no brown faces, hardly any Asian faces and no Aborigines. Foreigners were the Italian and Greek “new Australians”, and even they were rare in our (then) outer Eastern suburb.

Culturally, as more and more families spent more and more time around the television set, American culture rather than English, began to dominate our life.

We can’t remember exactly when we got a television set, just that it was bought specifically for watching cricket. As a family we watched the Australian serial Bellbird, which preceded the seven o'clock news. There were a succession of American sit coms we all watched, like My Favourite Martian, Bewitched, Father Knows Best, the Donna Reed show, Bachelor Father, My Three Sons and Mr Ed. After school I remember Clutch Cargo, Sea Hunt, George Reeves in Superman, and Hogan’s Heroes, F troop and Bonanza. And very rarely we were granted permission to watch 77 Sunset Strip. These are nearly all American titles. There were Australian and English shows too, but it is the American ones we remember.

With this American influence in our lives, and increasing prosperity, “teenagers”, a term first heard in the 1950s, emerged even more as a marketing target. For the first time, teenagers had their own music, fashion, language. I was more plugged into Teen culture than Sue. I began to go to local Saturday night church dances from about aged 14. There was always a live band who played rock and roll covers. A group of us from church would go.

Dress was quite formal, ties for boys and stockings and heels for girls. I remember the winter that plain coloured wool dresses with white crocheted collars and cuffs were all the rage: probably 1965. Auntie Bert, dressmaker to the wealthy ladies of Melbourne, made me a tailored aqua one with little kick pleats around the bottom.

Below is fourteen year old Margaret in the aqua wooden dress with while crocheted collar and cuffs.

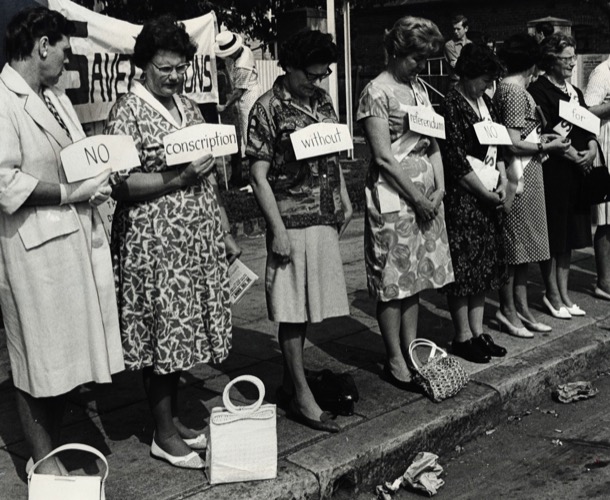

During the 1960s, Australians were entrenched in the divisive Vietnam war. Our family was by default anti war, and the “all the way with LBJ” policy of our government was fiercely criticised. In 1967, my boyfriend and another close family friend was conscripted for military service. Against huge opposition, the government had voted to call up into military service some twenty year old men. Many of them ended up fighting in the jungles of Vietnam. Our mother testified in court for the other friend, who was a registered conscientious objector. But many other friends and acquaintances went off to Vietnam with their hair shaved and very basic training. Some of those veterans live with the trauma of those experiences even today.

A "Save Our Sons" movement protested against conscription:

Gradually, public opinion in Australia, as in America, swung firmly against the war; and ordinary Australians demonstrated in the street.

By 1970, Sue and I had left school and were engaged in our tertiary studies, sharing a house in North Balwyn. University was still expensive, and we both managed it by gaining a bonded scholarship called a Studentship, which paid our fees, as well as a small living allowance. Even in a relatively enlightened family like ours, it was made clear that any family budget that was to be spent on university studies, was to be saved for our younger brothers, because they were boys.

1970s

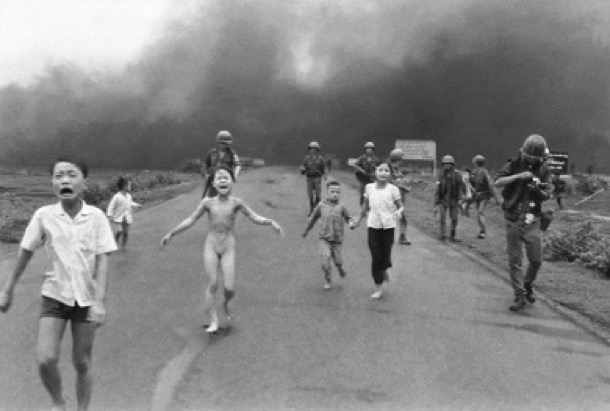

The 1970s was a decade of change for us personally, and a tumultuous time worldwide. In some ways, the decade was a continuation of the 1960s. Women, gays and lesbians and other marginalised people continued their fight for equality, and many Australians joined the world wide protest against the ongoing war in Vietnam. Outrage at the continuing conflict was fuelled by the graphic coverage of the brutality of war, available nightly on our TV screens.

Protest was bitter and violent.

By 1975 Saigon had fallen: a humiliating defeat for the USA.

There was more violence as Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge murdered 1.7 million Cambodians, and on the other side of the world, the IRA fought for British withdrawal from Northern Ireland.