Women's Work

Like women throughout history, most of the women in our family have had the primary job of parent and homemaker. Those homes range from simple pioneer cottages to majestic residences with grand staircases and sweeping verandahs. Nearly all of those women have also done paid work. And some of those who have not been specifically employed, have had supporting roles in their husband’s careers. Some jobs have been done by different family members across different generations.

None of our women have had traditional men’s careers, but, across the generations, we have covered a wide range:

AGRICULTURE (Dairy maid, Famers’ wives)

HEALTHWORK (Doctors’ wives, Aide, Occupational Therapy Assistant)

HOSPITALITY/TOURISM (Publican, Office Administraion, Horse Trail Guide)

RELIGIOUS SERVICE (Lay Preaching and other good works, Nun)

ADMINISTRATION (Postmistress, Sales Administration Supervisor, Office Administrator)

THE ARTS/CRAFT/DRAFTING (Whitework, Semco and Dressmaking, Drafting and Drawing Office, Drafting, Drawing and Card production, Art and Craft Activities for At Risk Children, Set Design and Construction, An Artist in the Hills)

RETAIL (Grocer, Checkout Chick)

SCIENCE (Laboratory Work)

EDUCATION (Teacher)

AGRICULTURE

Dairy Maid

Our paternal great, great grandmother, Catherine Bourke, née Kelly, worked as a dairy maid in Limerick before marrying Michael Bourke, and emigrating to Australia, in 1839. When they arrived in Melbourne, their first job was managing a dairy farm in Moonee Ponds. Catherine’s knowledge and skills no doubt influenced this decision.

The “famers’ wives”

A recent (2022) Guardian article tells us that, until 1994, women could not list “farmer” as their occupation on the census form. Instead they were viewed as “non-productive silent partners”. Even today, when 49% of real farm income is contributed by women, our image of an Australian farmer is almost entirely male. This puts “farmers’ wife” in this exploration in a particular light.

Another interesting aspect of these women from our family history is the divide between the wealthy squatters and the ordinary people of the land.

Martha Rye, the “poor little thing”, whose story we told in the June 2016 post, was a “farmer’s wife”, as was her mother, Elizabeth. Both of these women had very large families.

Elizabeth, our great great great grandmother, had eleven children. We can work out quite a bit about Elizabeth from a newspaper story, written about her husband, Adam’s life. She had worked in service, as a housekeeper, before she and Adam emigrated to Australia, in 1848. She could read, but not write.

They grew potatoes and onions, first on a rented farm near Geelong, then on two acres in Broadmeadows. The whole family would have been involved in the farm work, especially at harvest and market times.

We know that Adam not only worked as a labourer on neighbouring farms, but also spent time away trying his luck on the goldfields. It would have fallen on Elizabeth and the children to keep things going on the farm.

Martha, Elizabeth’s daughter, was married to Joachim. They would have had long days on the dairy farm, Heather Farm, near Kilmore. We learned a bit about her from her daughter Sarah, born in 1866. We wrote about this in August 2016. Sarah wrote with sentimental nostalgia about milking the cows, Blossom, Peggy and Strawberry; feeding poddy calves; working the separator; and rearing seventeen children. But between the lines, one can see the massive workload.

Around the same time, our paternal great great grandparents, John and Johanna McCormack, (later called Joan) acquired their 15,000 acre grazing property, Balham Hill, fifty kilometres to the west. So, in a sense, Johanna was also a “farmer’s wife”. But what a different life! John, a Justice of the Peace, and community leader, had staff to attend to the farm. Their four surviving children all went to boarding school in the city, for their secondary education.

Two generations on, Johanna’s granddaughter, our Auntie Tish, also married a farmer, near Warrnambool. Matt Rae was probably more of a hands on farmer than John McCormick, but he, too, was considered a grazier, and Tish’s life did not run to milking cows and feeding poddy calves.

Around 1950, close to the time Tish became a “farmer’s wife”, our mother’s aunt, Beat, and her husband Bill, sold their Surrey Hills grocery and bought land for a dairy farm in Cockatoo. The activities on this farm were similar to those at Heather Farm, a hundred years earlier: milking, feeding calves, working the separator. The difference in their lives is technological. An electric milking machine and separator, tractors, hay bailers, meant that they ran a dozen cows instead of three. And they had three grown children instead of seventeen. Nevertheless, they all had to work hard to make the farm pay enough to support them all. We wrote in detail, in our November 2017 post, about our childhood visits to this farm. There we described Beat’s pigs. This was her major farming contribution. She was not just a “farmer’s wife”, but actively involved in the decision making and physical work of the farm.

Auntie Beat

HEALTHWORK

Health work does not feature much among the women in our family. There are no doctors or nurses, that we know of.

Doctors’ wives

Our grandmother, Grace, and her daughter in law, Joan, were “Doctor’s Wives”. Wealthy, well connected, pillars of society, these women had no real job. In both cases, their husband’s surgery was within their house, but they were not required to deal with actual patients.

Among the women in our family, there are a few cases of unskilled health work.

Aide

Like so many women, our mother, Alice, “went back to work” when her youngest child was about ten years old, in 1966.

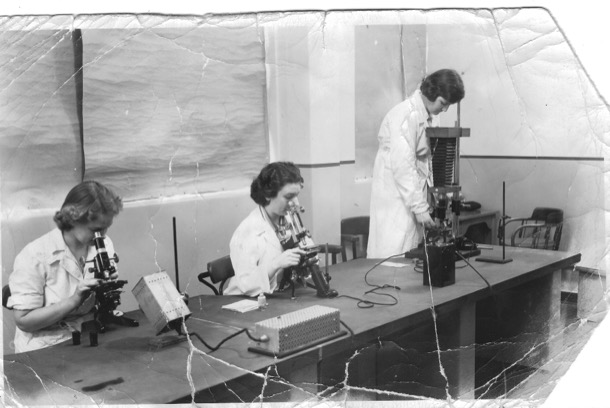

The only job she had had, since leaving school aged seventeen, was the wartime munitions work she had done at Maribynong, which today would have been called Lab Technician.

What skills did she have to draw on, apart from housework and parenting?

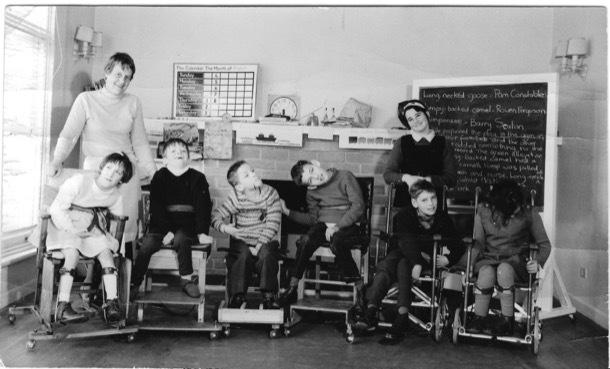

So her job as an “aide” at Lady Herring Spastic Centre was a low paid, unskilled one. She was assigned, with one other carer, to a “class” of Cerebral Palsied kids roughly the same age, none of whom had the ability to speak, and many of whom could not feed themselves. This was before the days of Communication Boards, so even the most able kids could not communicate much.

I, too, had a job at Lady Herring, after I finished school, and before I began the university year.

The centre was in Malvern, and Alice, and I, for the few weeks I was there, travelled by tram, along a very familiar route, down Riversdale Road.

There were a few qualified staff at the centre, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, but the program, such as it was, seemed to be up to people like Alice to devise. With the exception of the bus drivers, the whole staff, including the boss, was female.

The kids commuted on a special bus, and spent the whole day at the centre. Much of the time was filled with dealing with their physical needs, but there were excursions, shopping trips, walks around the neighbourhood, music sessions, and a memorable overnight “camp”. Although low status and poorly paid, it was stimulating, challenging work.

Alice with her "class"

Occupational Therapy Assistant

On the strength of my experience at Lady Herring, I did two other holiday stints as an OT assistant.

I worked with our OT friend Rikki, at Fairfield Infectious Diseases hospital for a little while. This was before HIV made it such an important place. My memories of Fairfield include the beautiful historic buildings; dozens of beds in a row, in the children’s Hepatitis ward; and the iron lung ward: people who had contracted polio as children and spent their life lying inside huge metal chambers that helped them breathe.

My job was mostly helping tidy up the activity room, and working in the ward with the Hepatitis kids: mostly bringing them things to do.

Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital

And then, during another long uni holiday, I worked at Montefiore (Jewish) Aged Care in St Kilda. It was perhaps 1970. Most of the Occupational Therapy “workers” there were volunteers: generally well off middle aged Jewish women doing their bit. One of those volunteers, who I remembered just as Mrs Hayman, later became Sue’s mother in law.

In my memory, the whole staff, except the doctors, were women.

In our centre, where the patients came to us, we ran activities like singalongs, bingo, games etc.

Many of our patients were post war immigrants from Europe, and some had been in Nazi concentration camps. It was the year that Melbourne emergency vehicles changed from sirens to “nee naw nee naw”, the same sound the SS vehicles had used in wartime Europe. When we heard the distant sounds approaching along St Kilda Road, we needed to be aware of some patients’ reaction.

I remember being told that that gentleman with his trousers barely held up with string, had been one of Melbourne’s top barristers. I still have the book called “Favourite Jewish Songs”, piano accompaniments I used for the singalongs I accompanied.

HOSPITALITY/TOURISM

Publican

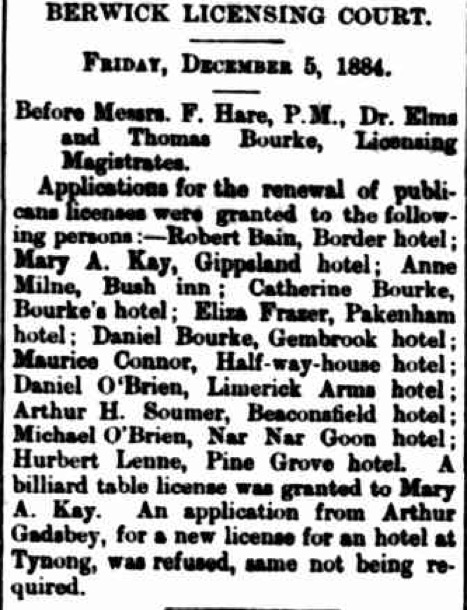

Catherine Bourke, in her new home near Pakenham from 1844, helped with the establishment of Minton’s Creek Run, the farm in the Toomuc Valley, that they bought with another family. But in 1850, they bought the Latrobe Inn, on the main Gippsland Road, in current day Pakenham. Catherine moved out of the slab hut up the Valley, with her seven children, and became a publican. The inn became known as Bourke’s Hotel. Michael was still very involved with the family, and they had another eight children, but it was Catherine who ran the hotel.

As well as a stopping place for travellers, Bourke’s hotel was the local post office, and a hub for the community.

Catherine Bourke

Horse Trail Guide

Catherine’s great, great, great, great, great niece Eliza, one hundred and seventy years later, also moved to the country to start a new job in tourism. Seeking a change from office work, Eliza moved to Mansfield to work for Hidden Trails by Horseback. This company runs trails in the Victorian High Country and also at El Questro Station in the Kimberly.

In Eliza’s own words her job entailed the following:

Up at the crack of dawn. Run the horses in. Feed the ones we are working that day. Brush and saddle the horses needed for the rides.

Determine the guests riding experience, match to a horse. Sign indemnity forms, Go through basics (stop start turn etc) and then lead the ride out, float in the middle of a big group, or tail the group at the back.

We go out on four rides a day:

*AM 2 hour ride (around the station)

*Kids intro ride (around the paddock)

*1 hour loop (around a different part of the station which includes the deep moonshine creek crossing)

*PM 2 hour ride (incorporation of the 1 hour loop with a look out stop where we would take a pack horse with drinks and nibbles and tie the horses up and have a sit down)

In between those rides we feed lunch to the horses working. Then back to the stables in the afternoon, Unsaddle, wash down and tip out the horses. And then do it all again the next day. Shuffling them around in different paddocks so we could keep them all in work.

There was 40 horses total.

Long days. Great experience.

Eliza at El Questro

RELIGIOUS SERVICE

Lay Preaching and other good works

Both our mother Alice and her maternal grandmother Emma Coates (née Dau) were staunch protestants and indulged in a little lay preaching and good works.

Emma Dau, one of seventeen children, was married to Alfred Coates, who was a Wesleyan Methodist Pastor. Emma’s married life consisted of raising a family, and her duties as the Pastor’s wife. Family stories tell of her devotion to these duties and of her riding around the parish on a push bike.

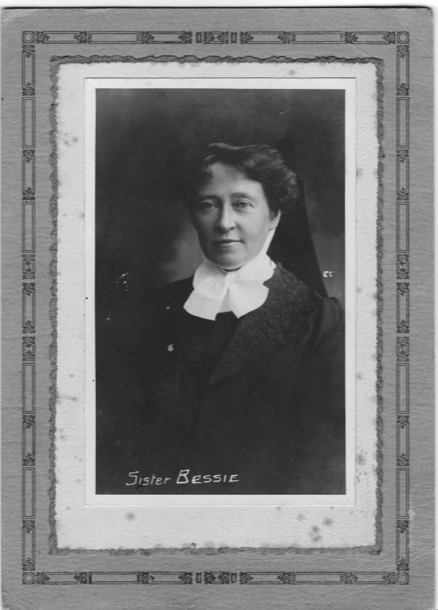

At some stage in her life, when our mother was still a child, Emma also became a Home Mission Sister and was known as Sister Bessie. As a Home Mission Sister, Emma wore an impressive uniform, that is described vividly by our mother and Auntie Marge, who as children were very impressed by this formidable woman. Here they are discussing her:

Sister Bessie

Sister Bessie worked at the Methodist Home Mission in Brunswick Street Fitzroy, in the 1920s and 30s. Sister Bessie’s work with the ‘fallen women’ and the poor, in the slums of Fitzroy was also vividly remembered by Marge and Alice. Sister Bessie’s good works involved anything from delivering babies to rescuing unmarried mothers. All of this was carried out ‘in the slums’ and in ‘poor, dirty houses’. One story has it that Sister Bessie once took off her own petticoat to give to a poor woman who did not have enough clothing.

The slums of Fitzroy were indeed slums, with a reputation for dirt, filth, disease and crime, a fearsome place. Streets were unpaved, there was no running water in many of the crowded and small weatherboard houses and children often ran barefoot.

So bad were the Fitzroy slums, that in the 1950’s they were demolished and the population was moved to the Housing Commission Towers, still standing in Brunswick Street.

Slums in Melbourne

Sister Bessie also travelled within Victoria and Tasmania. She was lay preaching, called ‘deputation work’ and raising money for the Home Mission. Apparently she was a very good story teller and must have not only impressed her young grand daughters but also her audiences, as she regaled them with stories from ‘the slums’. So impressed was one small child, that she gave up her doll ,to be given to the poor children who had no toys.

Half a century later Alice stood in her grandmother’s shoes at the same pulpit of a small, now Uniting Church, at Jung in the Wimmera.

Alice was also doing ‘deputation work’ in a fashion, preaching about world poverty and inequality. She was also raising money for the Uniting Church’s fight against poverty. Alice mentioned that her grandmother, Sister Bessie, may also have preached here. Incredibly a member of the congregation remembered as a small child listening to Sister Bessie preaching and telling stories. She said,“She was a wonderful story teller.”

Jung Methodist Church

The Nun

We grew up with stories of a nun in the family but knew no details. With the assistance of Google, we now know that Frances Bourke, [1883-1964] Jim’s Great Aunt, joined the Presentation Sisters, probably as a young woman, and became Sister Magdalen.

Presentation Convent was founded in Windsor in 1873, after a request by the Parish Priest for sorely needed teaching staff at St Mary’s school.

We are intrigued about Sister Magdalen and her role. Was she a teaching Sister or did she have another role at the Windsor Convent? Did she spend her life in the Order? Watch this space, hopefully more to come.

Presentation Sisters

ADMINISTRATION

Administration is part of many jobs, often the least pleasant part; writing reports, managing co workers, attending meetings, communication, ordering supplies, keeping records. These tasks are familiar to many workers.

Postmistress

In 1859 Bourke’s Hotel in Pakenham also became the community post office, ten years after Michael had bought the license. He became the founding post master of Pakenham. After his death, in 1877, Catherine became the Pakenham postmistress.

Up until 1901, each of the colonies operated their own postal service. After Federation, they all merged to become the Postmaster Generals Department (PMG).

Cecelia,(Cissy), Catherine’s youngest child, who never married, continued the role after Catherine’s death in 1910.

The job of postmistress would have involved taking sacks of mail to and from the Cobb and Co coach, later the train, and sorting it for people, who would come in to collect their mail.

Over time, the job of post mistress also included a savings’ bank, money order office and telegraph station; quite an important role in the local community.

Sales Administration Supervisor

But for a proper administration job, Tessa is our woman. Her job at Kenworth Trucks is to project manage the outfitting of each truck. She manages a team of people who put 22 trucks per day together, to the specifications of each customer. Keeping all the balls in the air, making sure everyone is gainfully employed, smoothing relationships with customers and between workers, maintaining records, supervising departments. It’s a very large and stressful job.

Office Administrator

Another organised young woman is Eliza who has also worked in office administration, at Nautilus Training and Curriculum, the company founded by her dad, Ian.

THE ARTS/CRAFT/DRAFTING

Whitework, Semco and Dressmaking

Three of our women worked in the textile industry, a generation apart. Both Great Aunts Bert and Beat and our Auntie Marge were involved in the embellishment of textiles with embroidery, and in dressmaking.

In our post on Auntie Bert, ‘A Sterling Character’, in March 2019 we explored ‘Whitework’. Whitework embroidery is the general term for hand embroidery worked with white thread on white fabric. It was used on many household items from babies’ bibs and tea towels to under clothes. Bert and Beat who, as young women, worked in this industry, probably worked in Flinders Lane. At this time it was the centre of the “rag trade”.

Auntie Bert, being unmarried, needed to continue in the workforce, but also be available to help her elderly parents with whom she lived. A talented and resourceful woman, she started a dressmaking business, working from home. Although self taught, her reputation for fine tailoring and expertly fitted ladies’ wear soon spread amongst the ladies of Camberwell and Surrey Hills. As her clientele increased and business grew, she had to move to bigger premises, and Bert leased space for a workroom and office in Riversdale Road Camberwell. This business is also described in our post ‘ A Sterling Character”

Drafting and Drawing Office

Our Auntie Marge worked in a number of drafting and drawing offices during her working life. After her short stint teaching, Marge began work in a drawing office in Collins Street, and then, during the war, moved to the drawing office at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory where Alice also worked. In 1941 Marge moved again, this time to the drawing office at ICI.

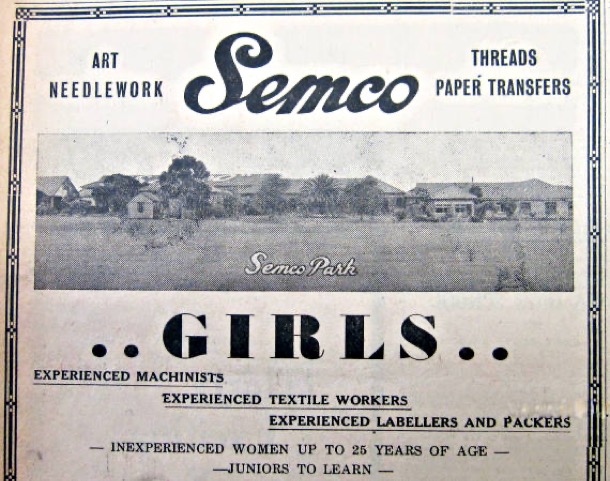

Later in life, Marge used her artistic talents at Semco, designing patterns for embroidery transfers. The designs were created as line drawings and printed onto tissue paper transfers, to be sold to women to embroider for items for the home, or as gifts. The transfers were ironed onto cloth after which the item could be embroidered accurately following the design. Margaret and I can remember embarking on an Semco embroidery project that I don’t think we finished.

Semco Workroom

Typical Semco Embroidery

Design subjects were flowers and animals, both European and Australian, cute houses, toys and even landscape scenes. Amongst the many items destined for embroidery were doilies, tablecloths and serviettes, tray cloths, handkerchiefs, babies’ outfits and children’s clothing.

Margaret and I can also remember visiting Auntie Marge at Black Rock and seeing her designs on a big drawing board. A working mother was a novelty for us, as our mother did not work outside the home.

The Semco factory and workshops located in Semco Park, Black Rock, was quite a progressive company and treated its employees well. They paid award wages to women, and provided recreation facilities for the staff, including six and a half acres of garden and lawn for their enjoyment. It was a large employer, as not only were the designs created and printed, but the embroidery cottons were also spun and dyed.

Marge worked for Semco as a part time employee, and at the same time studied Interior Design at RMIT. Both were unusual. For many women of her era, part time work outside the home was difficult to find, even once children were at school. Marge was fortunate to have Semco in her area and for it to be accessible on public transport. This allowed her to work there for many years, while pursuing her life long interest in further study.

Drafting, Drawing and Card production

Marge worked in a number of drafting and drawing offices during her working life. After her short stint teaching, Marge began work in a drawing office in Collins Street and then, during the war, moved to the drawing office at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory where Alice also worked. In 1941 Marge moved again, this time to the drawing office at ICI.

In between jobs outside the home Marge, like her Aunt Bert, started a business from home. Using her artistic skills and her design experience at Semco, Marge launched a greeting card business. She designed and screen printed the cards, packaged them and sold them to shops specialising in handmade original work.

Art and Craft Activities for At Risk Children

From this heading, it is obvious that this position could be fraught with difficulties. As a nineteen year old I was blissfully unaware of the worlds these children came from. Orana was a Uniting Church children’s home for at risk children and ‘orphans’. I remember mostly a group of cardigan and jumper clad children in skirts and shorts, traipsing into a linoleum floored space to participate in whatever I decided to do. I don’t remember anyone checking the activities, or that I had to run them past any of the staff. Some of the activities were very, very messy, but the children willingly helped me clean up. The confronting and difficult part of this job was not the behaviour of the children, but the heavy prevailing air of sadness in that place.

Set Design and Construction

Lois learnt woodworking from her dad. Together with her design and craft skills, she developed her “Top Props” business, designing and creating stage props. For instance, Deirdre’s Tappers’ concerts would not have been the amazing spectacle they were, without Lois’s colourful props.

An Artist in the Hills

Through her meticulous fine drawings and paintings Katherine explores a fantasy world inhabited by little creatures and characters, who are at home with spiderwebs and toadstools or nestled under gnarled old trees . Working from her house and studio in the Dandenongs, she is pursuing her interest in children’s book illustration.

RETAIL

Grocer

Our Great Aunt, our grandmother’s sister, Beatrice Morris (nee: Holm) owned a grocer’s shop in Maling Road, Canterbury, for a number of years. Bill Morris had previously worked at Lawson’s Grocer in Middle Camberwell , so having experience, this was a logical move. We are not sure how long they were in Maling Road but presumably Auntie Beat helped in the shop as well as raising a family of three boys. It must have been reasonably profitable, as during this time they built a house in Balwyn, and then sold the business to buy the farm, Sefton Park.

“Checkout Chick”

Anna, Beatrice’s great, great niece, is the only other woman in the family who has worked in retail, and this too was in grocery shop: the Renaissance Supermarket, Hawthorn, in the 1990’s: it was a supermarket of course. At sixteen Anna was keen to have a part time job and earn her own money. Her position was ‘checkout chick’, working on the register, before scanning of prices using barcodes was all entirely automatic. For instance, the checkout chicks had to memorise the PLU code for all the individual fruit and vegetable items, and this had to be entered on the register, manually.

SCIENCE

Laboratory Work

After the horrific use of chemical warfare (gas), on the European battlefields during the 1914-18 war, many countries began to work on ways to protect their populations from gas warfare.

Australia began its own “Chemical Defence” research program in 1926 at the Munitions Supply Laboratories, in conjunction with Melbourne Uni. They developed and assembled “respirators”.

By the time the second world war began in 1939, scientists were well advanced in this work. In 1940, over half a million respirators were manufactured at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory, and more than 500 people were employed there.

Our mother, Alice worked there, in the microscope section, testing the penetration of gas that came through the filters. When she would describe this work, she would indicate tapping and counting as she stared down the microscope. She had studied Year 11 Chemistry the year before she started.

Alice, left, working at Maribrynong

EDUCATION

Teachers

At least five of the women, in four generations of our family, have been teachers, some primary, some secondary.

The earliest we know of is our Nana, Alfreda, who taught primary school, before marrying Alfred in 1916.

She had fought for a chance to continue her education after secondary school. There was not enough money for university, and so she went to Melbourne Continuation School, which later became Melbourne High School. Its focus was teacher training and thus, after two years, Alfreda became a teacher. Presumably she taught for about four years. Women had to resign from teaching when they married.

Our Auntie Marge, Alfreda’s eldest daughter worked as a teacher for a year, straight from school. She taught 50 five year olds at Balwyn North, as a “junior teacher’. She also went to RMIT three nights a week dong Fine Art, her real passion. She only lasted one year, having decided that she was not suited to teaching. Our mother, Alice, while not actually teaching, worked as a school librarian assistant for the last years leading up to her retirement.

The next generation is ours, and at least four of us worked as secondary teachers: Pauline for a few years, and Sue, Anne and I until our retirements. All three of us did our initial tertiary education, including teacher training, on “Studentships”, which provided free education and a small wage, in return for three years service, usually in the country. Sue went to Sale, Pauline to Portland, and Margaret to Moe. Sue and and I wrote about our first year teaching experiences in a post on October 28, 2015, filed under “Young Adults 1970s”

Sale High School

Of our own daughters and nieces, only Anna has taken on the mantle of teaching. She even completed most of a PHD in Education. Recently, in her mid forties, she has gone back to the English classroom in a secondary school, where she is thriving!

Such a lot of different job experiences, and yet, within relatively narrow parameters. No astronauts, truck drivers or plumbers.

And, it must be stressed, the most important job for almost all these women, over six generations and nearly a century, is that of parent and homemaker.

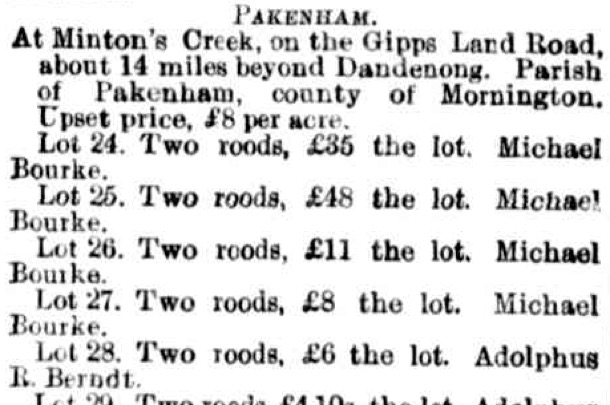

The Pakenham Bourkes 1939 - 2017 Part Two

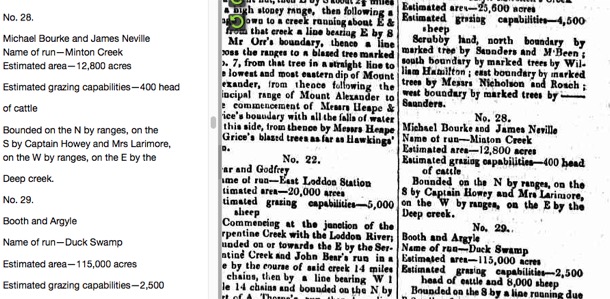

This example and a number of others are parcels of land around Pakenham.

Much of this investment was aimed at establishing their sons on large local properties.

Michael became an important citizen in the very early days of the Pakenham area. He was an inaugural member of the Berwick District Roads Board. Later this Board became the Berwick local council. Three of his sons were to spend time as Berwick Shire councillors, each of them spending time as Shire President. Michael was also post master and a trustee for the church, the school and the local cemetery. There is also record of nine nephews and nieces coming to Australia from Ireland, each receiving the best he could afford.

Michael died in 1890. Catherine took over the business and became quite a force in the district in her own right.

She lived into her nineties, dying in 1910. Her obituary describes her colourful life:

South Bourke and Mornington Journal Wednesday February 2, 1910

It is quite true to say that never in the history of this part of Victoria has the death of anyone been the general subject of so much interest and discussion as that of the late Mrs. Bourke who, with her husband, was one of the first settlers in Pakenham. The deceased lady was married in Ireland to Mr. Michael Bourke in the year 1838, being then 20 years old. Evidently the plans for their future had been prearranged, for the same day they shipped and sailed for Australia, arriving in Melbourne on St. Patrick's Day, 1839. They obtained employment as soon as they landed, managing a dairy farm at Moonee Ponds, where they remained until 1844, when, having saved money,they took up a run under a squatter’s licence on the Toomuc Creek, opposite Grant's orchard, then known as Bourke and Neville's station. There they remained for a number of years, until shortly before Black Thursday Mrs Bourke and her family took possession Bourke's Hotel, at that time known as the "Latrobe Inn," the husband remaining for a time at their station. On Black Thursday the whole district was in a blaze, and whilst Mr Bourke was trying hard to save the station property (water having been exhausted milk was brought into play and ultimately the run saved) word was brought to him that the hotel property at Pakenham was surrounded by fire. Galloping down there he found his wife and her children had saved themselves by crouching in the water in the bed of the creek. This is only one of many thrilling incidents in their lives.From the time they first arrived in this district to the time of Mr Bourke’s death in 1877, as they made money, they at once invested in land. Banks were unknown this side of Melbourne in those days, and their investments invariably turning out profitable, they slowly but surely acquired wealth. The name of Bourke and Bourke's Hotel will be, for generations to come, remembered as the pioneers and landmark of this part of Gippsland. The lives of Mr and Mrs Bourke have clearly proved what thrift, hard work and stout hearts can do in the settlement of this country, for at the time they arrived, the country was full of blacks camps along the banks of Toomuc Creek, and the country dense bush mostly. Yet out of all this Mr Bourke. made a fortune, buying up land as far away as Dandenong, and settling his sons on the land.

After his death Mrs Bourke continued to carry on and work hard, when there was no call for it, on the hotel property, and, as she repeatedly told the writer of this, she had more than her reward in the welfare and prosperity of her family, and she was proud of them, and well she might be, for her three surviving sons, Thomas, Daniel and David, have all been presidents of the Berwick Shire council, and all hold His Majesty's commission as Justices of the Peace, whilst the daughters are comfortably settled and highly respected. One of one of them, Miss Cissy Bourke has been (and still holds the position) of post mistress at Pakenham since a post office was first created.

With daughters like these, and sons holding the high positions they do, ever ready to give of their time and money in advancing the interest of the township and district, Mrs Bourke. has gone to her rest feeling fully rewarded for the years of her life devoted to and spent for their good. It would be difficult to find in the history of Australia, a parallel case of a man and a woman rising from the humblest rank of worker leaving behind them such a fortune and family so respected.

Mrs Bourke was probably the oldest colonist living at time of her death, having attained the ripe age of 91 years, being a colonist for 71 years and having resided at Pakenham for the last 67 years. She is said to have never, had a day's serious illness, and death was hastened by the severe heat three weeks ago.

Mrs. Bourke who died, on the 24th January at 9 in the morning, was-interred in the Pakenham cemetery on the 26th. A solemn Requiem High Mass was held in St. Patrick's Church from 10 to 12 a.m., the coffin being heavily draped in mourning, thronged with relatives and friends of the deceased. At the close of the Mass, the coffin was carried to the hearse and proceeded to the cemetery, a procession of carriages and horsemen fully half a mile in length and composed of people of all creeds following, and so was laid in her last resting place with sorrow and with respect: a good mother, a kind hearted woman, and a true colonist.

Michael and Catherine had fifteen children in total. Here in birth order is what we know of each of them:

James, born 1839, at Moonee Ponds. He was married twice: first to Johanna Conway in 1867, and secondly to Margaret Cahill in 1877. He had ten children all together, all girls. James’s property was in Dandenong, near the corner of Dandenong Road and the M1 freeway. He died in 1892 and is buried at Pakenham Cemetery.

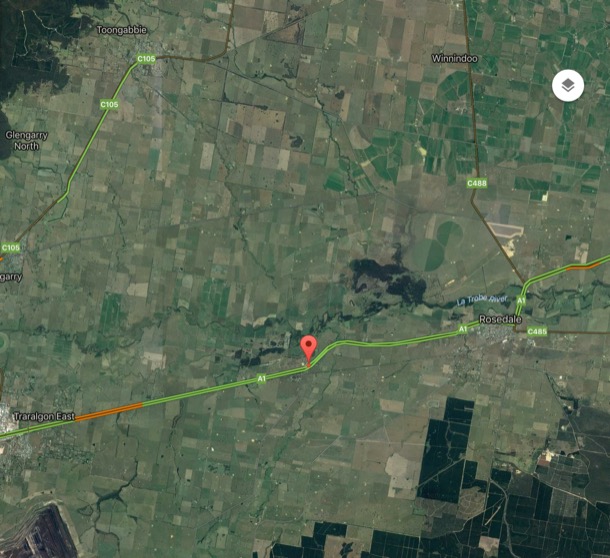

John was also born at Moonee Ponds, in 1840. He married Mary O’Neill in 1877. John and Mary lost their fist two children in infancy, but went on to have another five. The family settled in Leawood Park Rosedale, a long way from Pakenham. Today, Leawood is an Angus stud farm which has been in the same family, the Stuckeys, since 1944. It is a covenanted Trust For Nature property, protecting 18 hectares of important floodplain habitat along the Latrobe River.

John died in 1892, He is not buried in the Rosedale cemetery, but his son John who died aged 4, a year before John senior died, is there. Mary went on to live until 1935.

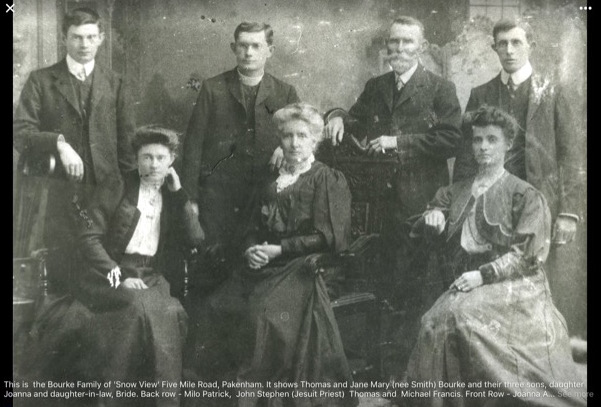

Thomas was Michael and Catherine’s third son, also born at Moonee Ponds, in 1842. In 1875, Thomas married Jane Smith, daughter of another family who came from Shanagolden in Ireland, and settled in the Toomuc Valley. The Smiths probably travelled from Ireland on the same ship as Thomas’ parents.

Thomas and Jane moved to the property “Snowview”, which Thomas had “selected” some time earlier. They had four children. Thomas, like his father, was very prominent in local politics, serving on the Berwick Shire Council for forty-five years. During most of that time he went on horseback from his home at "Snowview" to attend the meetings at Berwick, and it was only through advancing age that he finally resigned from the council. He lived at “Snowview” right up to his death in 1929. It is now a heritage listed property, which remains in family hands to this day.

Thomas and family:

Mary Ann was born a year later, in 1843 the last to be born at Moonee Ponds. Mary died aged six. We know very little about this Mary, we don”t even now where she was buried. The family was living at Minton’s Run when she died, perhaps she was buried near the slab hut they lived in. The Pakenham cemetery wasn’t formally gazetted until 1865, though, reportedly, there were burials there before then. A devastating fire in 1944 burned most of the wooden grave markers in the cemetery anyway, so much of the historical graves are now unmarked.

The fifth child is Michael, born in the slab hut at Minton’s Run in 1844. Unlike the other sons, Michael did not take up life on the land, but became a lawyer. He married Ellen (Nellie) Doogan in 1884. Nellie was the daughter of Pyalong publican, Hugh Doogan. The family lived in Parkville, near the city of Melbourne. Michael and Nellie had six children, the second of whom, Hugh, was our grandfather.

Michael died in !908 and is buried with Nellie and their third son Austin, in the Kew cemetery.

Michael and Nellie's Parkville house:

Michael and Nellie's grave:

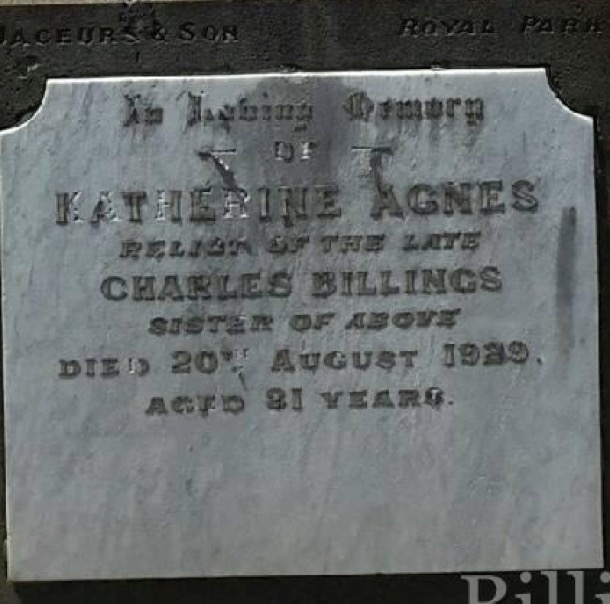

Catherine is the sixth child. She was born in 1845 at Minton’s run. She married Charles Billings in 1878. They lived in Prahran, in a house named “Pakenham”. It seems to have been an important family place, with births marriages and deaths all occurring there. Charles and Catherine had seven children and Catherine died in 1929, and is buried in the St Kilda cemetery with her sister Mary Lucy.

Daniel Bourke, was born in 1847. He was Michael and Catherine’s fifth son, Upon retirement from the Berwick Council, he is quoted as saying, “Our nation was not built on bloodshed, but on hard work”.

Daniel, like almost all of his brothers lived out this ethos on the land. Michael and Catherine seem to have imbued their children with the desire to do well, serve their community and ensure that their own children were also settled well. Daniel followed the family line. He married Fanny Levers who produced eight children and pre-deceased Daniel by only three years.

Daniel’s early years were spent in Pakenham where he owned Mt Bourke, some 400 acres, sold off from a larger property owned by the Hentys. This property is now in central suburban Pakenham, as we mentioned in the previous post. The heritage listed house was built one year after Daniel sold the property, probably by the new owners. David also owned the Gembrook Hotel in Pakenham.

What is notable about this article is that it also includes Catherine’s application for Bourke’s hotel, and Daniel’s brother Thomas, is the licensing magistrate!

It is Daniel’s public life in Pakenham that gives us some idea of the man. Daniel served on the Berwick Council for twenty years and it is the speeches from his farewell dinner that offer these insights. Fellow councillors were obviously very sorry to lose his services, as they commented that,

‘…his name will be remembered in Pakenham with pride and honour..’

‘Berwick Shire is losing on of its leaders.’

‘He was one of the largest-hearted men in the district….’

‘His calm, cool, warm-hearted manner won him friends from all ranks. He was in the full sense of the word a reliable man and a gentleman.’

Daniel held many other other positions the community, as President of many clubs, farming organisations, and was also regarded as a pillar of his Church and well regarded by others…’

Daniel’s own speech in reply to all these accolades is also revealing. In reply he says that it was the noblest duty of a man to help his neighbour and the magnificent national feeling that was through gathering particularly pleased him. Australia to him was the greatest country in the world.

This offers an insight into Daniel’s character but also to the ethos that appears to run through the family, and no doubt contributed to their success.

Daniel and his family moved to Stratford where he and David, his younger brother of Monomeith fame, owned another property, ‘llowalong’. Daniel and his and wife felt that there was not enough ‘scope’ for their sons in the district and it was for their sake they were leaving Pakenham. Daniel died at the ripe old age of 88 leaving one of his sons possibly James on the Stratford property.

Mary Lucy was probably the last child to be born at Minton’s Run. There are doubts about the date of her birth. Mary Ann had recently died, and this Mary was perhaps given her name. She died, unmarried and is buried in the St Kilda cemetery. On her grave it says she was aged 37, but this would make her born the same year as her namesake Mary Ann. Had she lied about her age? Is the information about the two Marys wrong, and they are the same person? We don’t have a grave for Mary Ann, so there are unanswered questions about these two. The fact that Catherine was buried in the same grave as Mary Lucy, and near to Prahran, when Catherine lived suggests that the two were close. Perhaps unmarried Mary lived with Catherine and Charles.

Ellen was the first child to be born at Bourke’s hotel right in Pakenham. She was born in 1851, the year of the big fire that burned the Minton’s Run property. She married John Augustus McKeone, of Port Albert Victoria. The couple lived at times in Beechworth and in Narrandera. They had a total of nine children. John died in 1895 and Ellen in 1934.

Milo was born in 1852. He never married. He died aged only 25, “after a short illness” at the home of his older sister Catherine, and is buried in the Pakenham cemetery.

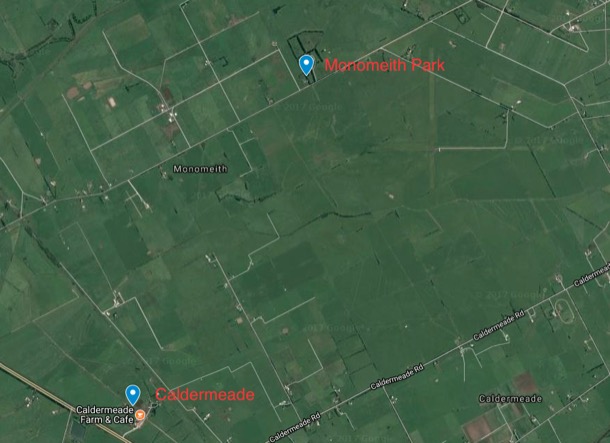

Michael and Catherine’s youngest son David, was born in 1856. He married Mary Hunt in 1888. David had bought Monomeith Station in the mid 1800’s. It was originally 3000 acres comprising what is now the area of Monomeith and Caldermeade.

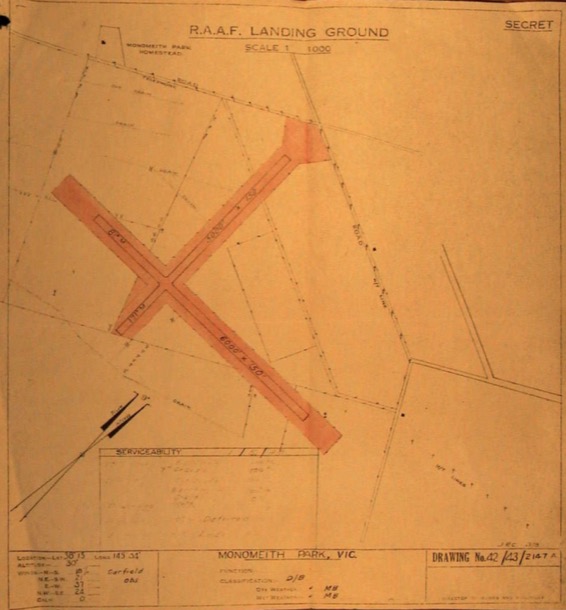

On the map you can see the World War two airstrip, south east of Monomeith Park. It was constructed as a RAAF fighter base to protect Yallourn where all of Melbourne’s power came from. In the end they only built two gravel strips, in the shape of a cross.

It was fine grazing land on black loam country and is part of the rich history of the early settlement of the area. Over the years hundreds of prime bullocks were driven to Newmarket sale yards in large mobs. According to local legend this feat was undertaken by the well-known character “little” Billy Matthews who reputedly drove the Monomeith mob all the way by himself.

In 1886 1000 acres of Monomeith was sold at auction, probably the swampy section. The carrying capacity of the land retained is referred to in, “Memoirs of a Stockman” by Harry Worthington Peck:

“However, the Bourke brothers [David’s sons, Michael and Hugh] at Old Monomeith Homestead of some 2000 acres have today the pick of the estate carrying some 3000 cattle of mixed ages and all fattening. This is probably a record for the Commonwealth and proves the virtue of top-dressing even on the richest natural pastures”

The Cattle King, Sir Sidney Kidman, visited Monomeith for both business and pleasure, another indication of how well known this property was.

In later years the property was again subdivided presumably between David’s two sons Michael and Hugh. Their descendants retained ownership until recently. Ironically after so many years in family hands, through three generations, we have discovered both the properties in advertisements in the real estate section of the Weekly Times.

Caldermeade was sold in 2016.

Through articles and advertisements for the property, in the local paper, we discovered more family history. For instance, only four years ago, there was an article in the Pakenham Gazette about Brian Bourke, the then owner of Caldermeade.

A fall from a horse, broken bones and 32 hours lying in a paddock would spell disaster for most 77-year- olds, but Hughie Bourke comes from tough stock. Fearing the worst, family and friends rallied together last week to rescue the stricken grandfather after he was reported missing last Thursday. Now recovering in The Alfred hospital with a shattered femur and pelvis, Hughie reckons he spent his marathon ordeal enjoying the company of animals on his Caldermeade property, but was disappointed to miss the day’s horse racing. Falling from his horse, he remained injured on the ground for almost a day and a half, watching the changing sky and surrounded by foxes and cattle. And while “the old cockie” has a long road to recovery ahead, he told his kids that it was a “bloody beaut” watching the clouds go down and sleeping next to the animals on his farm.”

Monomeith is on the market at the time of this post, July 2017, thus ending three generations of Bourkes running cattle on this property. An article published in the Pakenham Gazette describes the property:

‘Monomeith is heritage listed by the Shire of Cardinia because the house, which was built about 1899, and trees represent a long-term farming enterprise carried out by one family.

The old woolshed, and early picket fences and gateways that survive along the frontage and in some of the paddocks are a reminder of times gone by.

The large double-fronted weatherboard verandah farm house has been home to the Bourke family for more than a century.’

Margaret was the twelfth child of Michael and Catherine. We do not know the exact date of her birth but we know she married Robert Massey Coote in 1883. In 1886, in partnership with Lance Herbert the Cootes established a store and transport business in Orbost. They had three children. Robert died in 1891, and Margaret in 1935.

Agnes’ birth date is also unknown, but we know a little about her life. She married George Fraser of Aberdeen, Scotland. The family lived first in Nar Nar Goon and then in Aukland, New Zealand. They had six children, three born in Australia, and three in New Zealand.

Richard is the next child, but he died in infancy

Cecelia (Cissy) was Michael and Catherine’s fifteenth and youngest child. She never married.

The original Pakenham Post Office opened on 1 February 1859, with Michael as the postmaster. Catherine took over when Michael died in 1877, and Cissy took over from her, serving for many years. The history of Pakenham Post Offices is a bit garbled because, once the railway station opened, in 1977, there were two. Post Mistress was an important official role. For instance Cecelia’s name appears in 1909in the official Federal Gazette as the Electoral Registrar for Pakenham.

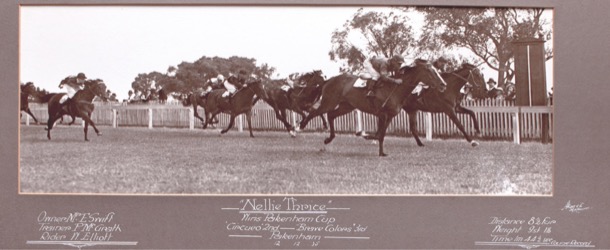

THE BOURKES : A RACING DYNASTY

From the early days at Bourke's hotel, Michael showed an interest in horse racing. We have no idea if this interest arose in the colony, where impromptu race meetings were common, or whether the interest came with him from Ireland. As Ireland has such a long and rich history of horse racing, this is quite likely.

Records show, that Michael and Catherine lent the paddock behind their hotel for the first race day picnics at Pakenham. This area was later named Racecourse Road. With great enthusiasm and involvement from Michael and his sons, racing flourished and in 1875 the Pakenham Racing Club was formed. Michael’s sons continued the family involvement, guiding the development of the club after Michael’s death in 1877.

Our direct descendant Michael, fourth son, left Pakenham for a law career in Melbourne. The rest of the family that remained in Pakenham continued to build a racing legacy.

David Bourke, the youngest son and owner of Monomeith Park, was a particularly good horseman and it is his line that continued the public involvement in racing through to the present day. David helped the Club to prosper in the early days, making his back paddock available for race meetings. This area was later named Racecourse Road, and was the site of the Pakenham Racing Club until 2014.

In the 1900’s the club fell into semi obscurity.and the Bourkes once more became involved in response to:

‘a letter from a local policeman to the Chief Secretary’s Office prompted an official letter being sent to the Pakenham Secretary Mr. A. L. Fairburn, requesting action be taken to rectify the situation.’

Hugh and Michael Bourke, David’s sons, came to the rescue, raising 4,000 pounds to reconstruct the course. The course was seven furlongs, 54ft. (1424m) in circumference.

After David’s death it was his sons Hugh and Michael who played the crucial role of keeping the club alive and it continued to hold picnic race meetings. The land was leased to the club by the Bourkes for no fee on condition that profits were spent on public amenities.Finally despite pressure for the site to become Crown land,the Bourkes agreed to sell the track to the Pakenham Racing Club for 25 000 pounds ($50 000). The deal was finalised in 1957.

"It was about a quarter of what it was worth,but back then our family wanted it to stay a racetrack forever and we always thought it would, " Hughie Bourke is quoted as saying.

The Bourkes maintained their interest in the club after the sale, serving on the committee and fulfilling other roles. Michael, David and Gavan held the position of Secretary between the years 1926 and 1999. A number of other family members also served on the committee for lengthy periods of time.

Early this century as the suburban sprawl reached Pakenham the racing club committee decided to sell the land and use the considerable profits to redevelop a new racing track at Tynong on a site of 246 hectares. In February 2014 the cub hosted the last race meeting at the old site and at the time, Gavan Bourke commented that it was sad that the old track,on a 27 hectare site had been sold for redevelopment to accomodate the urban sprawl.

The Bourke family interest in racing is also evident in positions held within the Victorian Racing Club [VRC] by David’s direct descendants.

David Bourke [1930-2005] David’s grandson, was a racing administrator for 60 years. He began his career after his father’s death when aged 19 he took over as Secretary of the Pakenham Racing Club.

He served on the VRC committee for twenty years, seven years, as Chairman. In this role he presided over the nation's most famous race, the Melbourne Cup from 1991 until 1998. The David Bourke Provincial Plate is run annually in June at Flemington, the Saturday of the Queen's Birthday weekend.

David’s brother John, also had a career in the thoroughbred racing industry. He was employed by the VRC as the Veterinary Steward. During a long and distinguished career he was instrumental in the introduction of drug testing of thoroughbreds. Dr Bourke went on to become a world authority on equine medicine and the use and effect of drugs on horses.

So from the first race meeting in Pakenham, in the early days of the Colony of Victoria, Michael’s and Catherine’s descendants have been involved in the horse racing industry. Some, such as our line, have had a recreational interest in horse racing whereas others, such as David’s line, produced several Bourkes who made their careers in thoroughbred racing. Quite a family affair through the generations!

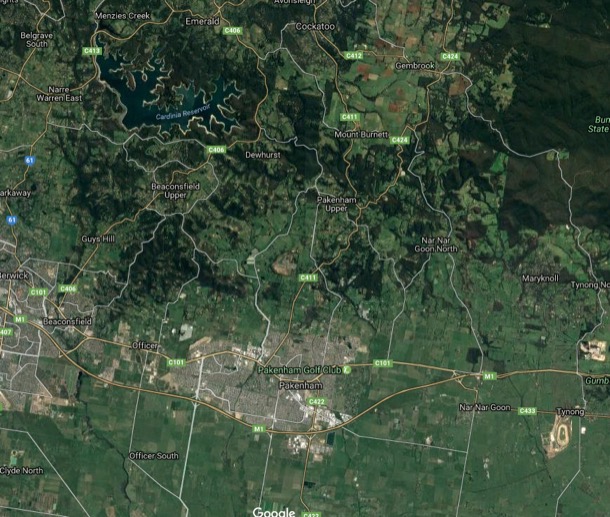

Pakenham, the visit

So, in May 2017, one hundred and seventy-three years after our great, great, grandparents Catherine and Michael Bourke selected Minton’s Creek Run, we stood on the very spot. In 1844 the area was probably grassy woodland, open country, well grassed and with shade for the cattle. Like in so much of Victoria, the early settlers, our great, great grandparents amongst them, could just take possession and let their stock loose. Today the area is still a pastoral landscape but obviously broken into smaller holdings. Minton’s Run appears to be quite hilly, rising from the creek to the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges in the North, and undulating to hilly country in the East and the West.

It must have been a hard life. The day we were there was cold, and after recent rain the ground was soft and muddy. Not much fun carrying water from the creek in this weather. Presumably Michael and Catherine’s bark hut would have been near this water source but up on the hill a little, safe from floods and away from the soggy creek flats. We walked a little way along the dirt road imagining Michael and Catherine building their bark hut, collecting water from the creek and tending their stock.

Turning south, we drove to Pakenham on the Toomuc Valley Road. It would have been an easy, flat, gallop downhill to the hotel site on the corner of what was, and still is, the point where the Princess Highway crosses the Toomuc Creek.

Not so easy for Michael, the day he galloped this way to rescue his family during the 1851 bushfires. Parking opposite the hotel, we walked the short distance to the creek, quite a substantial one, especially after rain. This is the spot where Catherine and the children sheltered from the flames, and where Michael found them safe and sound.

From this side of the road the heritage-listed original chimney is clearly visible. The hotel is undergoing yet another extension and renovation but the old bricks are just visible at the corner of the chimney where the layers applied over the years are crumbling away. Today the hotel is an ugly pile of add-ons and extensions including prominent Thirsty Camel drive through bottle shop. The chimney lives on, as does the business, obviously still thriving.

What next? As Pakenham Cemetery was nearby, we thought it fitting that we see where our great, great grandparents were buried. The cemetery is on a hill above the highway which was the main road to Gippsland, back when Michael and Catherine offered a stopping place to travellers. Nowadays, though still busy, and still called the Princes Highway, it is bypassed by the Princes Freeway.

We had seen a picture of Michael and Catherine’s grave, and so had seen the shape of the cross on the top, but the picture had not shown where it was, nor had we been able to read the writing.

It’s not a very large cemetery and soon we found an area with various recognisable Bourke names.

We should have known just to walk to the highest spot! There was the patriarch towering above everyone else.

Michael and Catherine's grave:

Here is the original newspaper article about Michael’s death in 1877:

We regret to chronicle the death of Mr. Michael Bourke, the oldest inhabitant, as we understand, of Pakenham, whose remains were laid in the Pakenham Cemetery on Wednesday last. His death was accelerated by an accident, which, although it might have had but little effect on a younger man, hastened his end. A few days before his death he had gone up to the hay-loft of his stable to pull down some hay, and in descending the ladder missed his hold and fell heavily on the side of his head. At first it was not considered that be was much injured, but continued to get worse until be died. Although it rained almost incessantly during Wednesday the funeral was a very .large one, comprising most of the old residents for many miles around, by whom deceased was generally esteemed. About three o'clock the cortege started, the body being conveyed in a splendid hearse, followed by vehicles containing deceased's wife, daughters, and other female relations, his sons following; after whom came a number of vehicles, and, lastly a very long array of horsemen. The funeral service was conducted by Mr. D. J. Ahern, of Dandenong, in an effective manner, although during the ceremony the rain was falling very heavily. - From a first visit to the Pakenham Cemetery we cannot say much in praise; of the residents who permit it to remain in its present state so long. There are only five acres of it, which were granted by Government, and it is not creditable to the, residents to allow it to remain almost in its natural state.

The cemetery was very well kept on the day of our visit, and is clearly still in use today. We saw many names we recognised, such as James, Michael and Catherine’s eldest and his daughter Nellie, who had died, aged 17. We noted that four of Nellie’s uncles carried the coffin, including our great grandfather Michael, by then living in Melbourne.

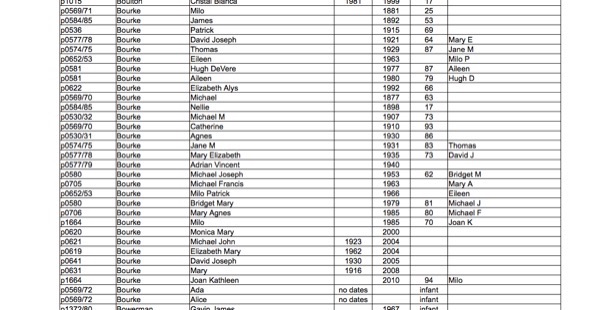

Here is a list of all the Bourkes buried in the Pakenham Cemetery:

Looking down on the sprawling suburban growth that is now modern day Pakenham we could just see where another piece of Bourke history still stands, Bourke House. We drove down and pulled off the busy feeder road to the freeway into what will become the gateway to a new housing estate. It will eventually swallow the last vestiges of the first Pakenham Racing Club track that the Bourkes were instrumental in setting up. Today the track still visible surrounded by mud, trucks and cyclone fencing. Margaret and I approached Bourke House, right next door.

This racecourse residence and stable complex is heritage listed as it is a large, successfully designed and well-preserved residential complex from the 1920s, linked with a private racecourse and associated with notable district figures, such as the Bourkes, prominent Pakenham graziers and horse racing identities. Through its associations with the Bourke family who have played major roles within the Victorian Racing Club, and with the Pakenham Racing Club, this property has been significant in the history of racing in the shire.

The house and stables now sit behind a locked gate next to the sea of mud that was its racetrack. Hopefully when the housing estate is complete the house will also be tidied up and put to use again.

As we sat in the car, map in hand, we realised that, within walking distance of Bourke House, were several significant Bourke properties: the Bourke’s Hotel, the youngest son, David’s first property Homegarth, and the fifth son, Daniel Bourke’s Koo Man Goo Nong which he changed to Mt Bourke.

Homegarth and Mt Bourke have been absorbed into suburban Pakenham. Homegarth no longer exists, but the reminder of its existence is in the name of a playground and Childcare Centre nearby.

Mt Bourke is now a housing estate.

We drove and walked around the housing estate looking for acknowledgement of the history of the area, or directions to the original house. We found none and presumed that the house had been destroyed in the name of progress. But no, on the way home we were enlightened, at, of all places, the ‘Olivers' fast food outlet on the Monash Freeway. Collision of two worlds: as the chatty young lady passed us the coffee and egg sandwiches, she told us that she lived in that very estate, and yes, the house still stands at the top of the hill. Now the house looks down at the closely packed phoney heritage houses and other trappings such as Stockyards Playground, instead of productive fertile creek flats.

Koo Man Choo Nong/Mt Bourke:

A little further out of town we found Snowview, owned by Thomas, Michael and Catherine’s third son. We could just see the ranges through the drizzle, a wonderful view. No wonder Thomas called his property Snowview. Still in family hands, Snowview is now an equestrian property. It stands at the corner of Bourke Road and Five Mile Road, and is bordered by very, very old, gnarled cypresses. Maybe Thomas planted these as a wind break from cold winds from the ranges?

It was getting late but we decided to attempt to find Monomeith, originally owned by David, the youngest son. Monomeith, still on the map, is situated on rich farming land at Nar Nar Goon. The roads were busy with trucks and commuters, very unpleasant driving conditions in the rain, but we soldiered on through several wrong turns, until we decided also to head for home. We now know, after further research, that we were very close. An excuse to go back another day.

The Pakenham Bourkes 1839 - 2017 Part One.

New South Wales had been settled as a convict colony in 1788, when the first fleet arrived. Over the next fifty years, many convicts were transported there, and many English free settlers chose to try their luck in that distant land. By the 1830s, there was clearly a need for more immigrants in the colony. Not only were there three men to every woman, but the balance of convicts to free settlers was all out of whack. There were not enough reliable, trustworthy labourers to work on all the properties that had been developed, especially all the sheep stations.

A committee was set up to address this issue. It looked like a win-win situation with England, where the population had outgrown the rural jobs available. It should have been easy to entice the right kind of working people to settle in New South Wales. But America was also expanding, and was a fifth of the distance. It was hard to persuade people to undertake a perilous sea voyage to New South Wales instead.

A scheme was set up, whereby young country women of good character would have their sea passage paid for, and be guaranteed a job as a servant in rural New South Wales.

Predictably the people whose task was to head off into the countryside and interview young unmarried women of good character, took shortcuts, and, by the sound of it, simply herded up the “mere sweepings of the streets of London” who were all too happy to take the money.

On one large ship, the David Scott, 226 single females came out to New South Wales. Mr Marshall, Royal Navy, the hapless “superintendent” of the ship said of the 226 “there were not more than twenty-five that I would consider suited for country servants”. Furthermore the David Scott was a very large ship and there were more than fifty men in the crew. They seemed to have been totally out of control ‘they .. had unrestrained intercourse with them during the voyage” (in this context ‘intercourse’ just means anything from unsupervised conversation to what it means today) ‘I do not allude of course to the whole of the women, but to upwards of forty of them, whose abandoned and outrageous conduct kept the ship in a continual state of alarm during the whole passage’

The committee overseeing this scheme were supposed to have “personally questioned every female for the purpose of ascertaining her age, occupation and qualifications in other respects for the colony. Either the powers of dissimulation (lying) possessed by abandoned females of the lowest grade must be very great indeed and must be well backed by forgery, or the gentlemen of the London committee must have been marvellously unskilled in discriminating character.”

After this debacle only small ships were used, and many other checks and balances were put in place, including the selection of potential migrants. It is in this context that, in 1838, Governor Richard Bourke contacted his friend, Thomas Spring -Rice, Baron of Monteagle, and landlord to young Michael Bourke of Foynes Island Shanagolden, County Limerick, Ireland.

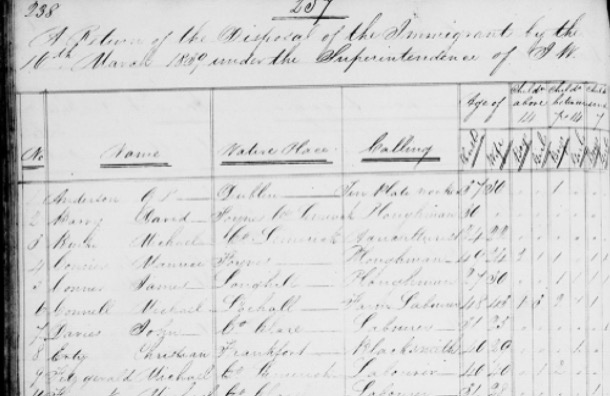

Governor Bourke asked Spring-Rice to carefully select suitable people to participate in a scheme to emigrate to New South Wales, and, in particular, the newly colonised area of Port Phillip. In 1839, 13 families who had been Spring-Rice’s tenants, including Michael and his new wife Catherine, emigrated to Australia on the Aliquis. Most settled in the Port Phillip area. By 1858, about 800 ‘Monteagle emigrants” had settled in the new colony.

Monteagle county in New South Wales, containing the towns of Forbes and Bathurst, is named after this Irish nobleman.

So Michael and Catherine Bourke, our Irish great, great grandparents, and founders of the Australian branch of the Bourke family, arrived in Australia on St Patricks Day, March 17th in 1839.

On the ship's list, Michael, 24, is listed as an “agriculturalist”, with his unnamed wife aged 22, though perhaps she was only 20. Catherine had in fact been a dairy maid back in Limerick.

Close up of the Aliquis passenger list. Michael Bourke (misspelt as Burke) third on the list.

In an interview, carried out when Catherine was a very old lady, she said that they were married in Cork City, just before they left for New South Wales on the ship Aliquis,

And yet, when they arrived at Sydney, on March 2nd 1839, Michael and Catherine lost no time in seeking a priest to bless their marriage, and on Saint Patrick’s day, the ‘Banns of Marriage’ were read for the first time. It was at St Mary’s cathedral in Sydney where, 22 days later, the couple made their Vows of Marriage, on April 8th before Fr Francis Murphy and their friends from their home parish of Shanagolden, who had traveled with them from Ireland.

Work in Sydney was scarce and the ship John Barry took them along with most of their fellow travellers to the newly laid out town of Melbourne. Michael and Catherine spent their early days in Moonee Ponds, managing a dairy farm. The first three sons, James, John and Thomas were born there.

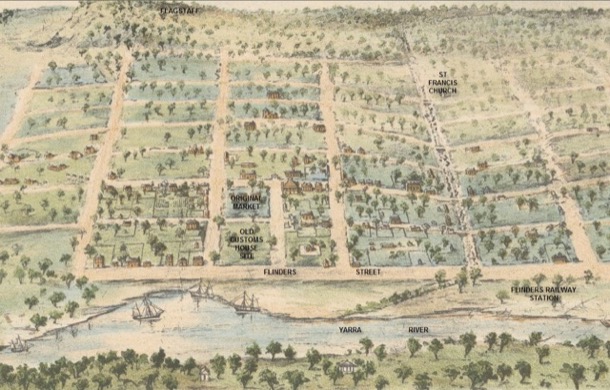

Just four years before Michael and Catherine Bourke arrived in what was then the Colony of N.S.W., Melbourne had begun its ramshackle development. John Batman, entrepreneur and settler, signed a treaty with aboriginal occupants of the Port Philip District, the Kulin nation. He promptly claimed over 500,000 acres north and west of present day Melbourne and also famously declared the present site of Melbourne’s CBD, as the place for a village. The then Governor of the Colony of NSW, Governor Bourke, became concerned at the unruly and illegal occupation of land, and took charge, declaring all settlements invalid. He appointed Captain Lonsdale to represent him and run the settlement of Port Philip. Fees for grazing rights to squatters were imposed, and Governor Bourke approved Hoddle’s plan for the streets of Melbourne. This is the new world which Michael and Catherine entered, as they stepped off the boat to begin their new life.

Hand drawn map of very early Melbourne, around 1837

The family moved to near Pakenham in 1844, with their friends the Nevilles, who had come out on the Aliquis with them from Limerick. Under the partnership names of Neville and Bourke, they settled in the Toomuc Valley area, taking up the “Minton’s Creek” run, which extended towards Upper Beaconsfield, 12,800 acres, about 5 square kilometres. Here, our great, great grandfather, Michael, was born in their ‘slab hut’ home in 1844.

Minton's Creek Run covered the whole of present day Pakenham Upper

The Minton's Creek house site was in the centre of this aerial photo

In 1850, the Bourkes bought the Latrobe Inn, a hotel on the main Gippsland Road, where the Toomuc Creek (also known as Bourke’s Creek) crosses the main road. It became known as Bourke’s Hotel. Catherine and the seven children they had by then moved to the hotel to manage it, while Michael stayed at the station.

Bourke's hotel

Only the original chimney stands today.

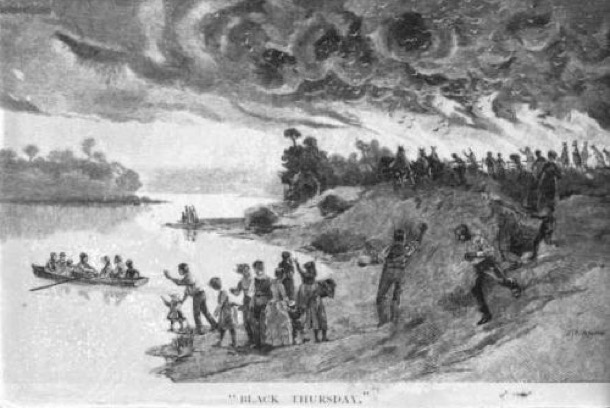

In February, 1851, after a prolonged drought, a massive bushfire covered a quarter of what is now Victoria. The smoke blew on strong hot winds, wreathing Northern Tasmania in thick smoke. It became known as Black Thursday. The story goes that Michael fought the blaze, first with water, and then milk from the dairy.

Word reached him that the hotel itself was surrounded by fire. He galloped down to Pakenham, and there he found that Catherine and the children had hidden in the Toomuc Creek bed and had escaped the blaze, and that the hotel itself had not burnt.

from Black Thursday, a painting in the State Library

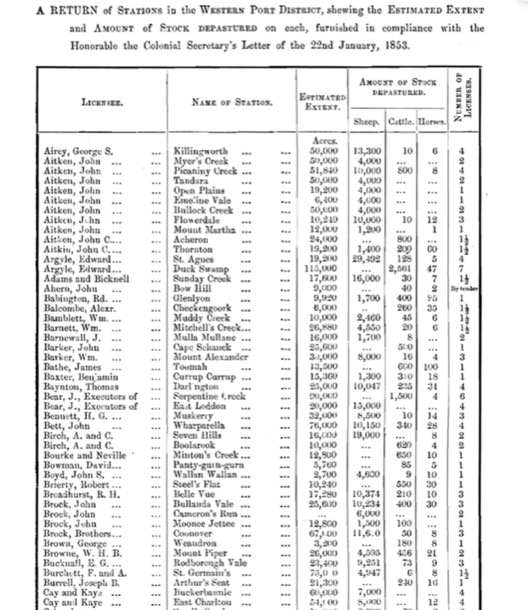

They restocked the property, and, in an 1853 census, it was reported that Bourke and Neville had 650 cattle and ten horses on their 12,800 acres.

Bourke’s Hotel became one of the best known stopping places on the way to Gippsland. Later it became the Princes Highway Hotel and its chimney is still there today.

It was a real hub of the district. It was the polling station and the post office for the area, and Michael Bourke was postmaster at Pakenham for 30 years. After his death, in 1877, Catherine, and unmarried daughter Cecelia, continued to run the post office.

In his 1942 book Memoirs of a Stockman, Harry Huntington Peck wrote:

Old Mrs. Bourke who was the landlady of the Pakenham hotel at the bridge over the Toomuc creek for so many years was an institution of the district. She was most popular with the Gippsland travellers and drovers as she took pains to make all visitors comfortable. Her fine sons David and Daniel prospered as graziers and bought good properties, the one Llowalong originally part of Bushy Park on the Avon near Stratford, and the other Old Monomeith, where the next generation Hughie and Michael, trading as Bourke Bros., are today the largest regular suppliers of baby beef to Newmarket, are well known as the owners of show teams of first-class hunters and hacks, and of late years, have been very successful in principal hurdle and steeplechase races.

It was at Bourke’s Hotel that the remainder of the children were born. There were fifteen in all, but two died in infancy.

Gradually the family grew to adulthood, and, when large areas of land were thrown open for “selection”, all the boys in turn gained properties.

Some of them are still in the hands of their descendants.