October 2015

First Year Teaching

28 10 15 16:42 Filed in: Young Adults 1970s

Teaching was an obvious, perhaps the only, choice for us to study after Matriculation (Year12). The Commonwealth Government provided scholarships to cover fees, but the State offered studentships for prospective teachers, which had a wage as well. Women studentship holders weren't allowed to marry until they finished their course. Margaret remembers the Monash Teachers College Principal at an initial meeting with all studentship holders from the uni, saying, "If he's tall, dark and handsome, tell him he has to wait for you for four years." Both men and women had to apply for country schools and go wherever they were sent for their first year of teaching. After that they were free to apply elsewhere. This meant that country schools had a succession of inexperienced first year teachers. Both Sue at Sale and Margaret at Moe had seventeen first year out colleagues during their first years.

LIFE OPENS UP AT SALE HIGH SCHOOL 1971

What a learning curve!!! Out in the wide world and what a wonderful world it turned out to be; very scary for a few months but exciting. The scary part was the teaching; the exciting part was the socialising and the ‘abentures.’

Having been granted a studentship I was legally bound to apply for country schools I was more than happy to do so and applied for Mansfield, Alexandra Omeo Corryong etc etc. We had to apply for at least twenty schools and I hoped I would be appointed to one of these most desirable of locations so that I could learn to ski and continue bushwalking. I was appointed to Sale High School and informed in the letter to report at the beginning of Term 1 1971 to Mr A Aitchison, the Principal. Terrifying reality.

I set off the day before the beginning of Term 1, all my possessions crammed into my Hillman Minx, and headed off to a new life and a huge learning curve. I had booked a room at the Midtown Motel in Sale, this in itself a new experience, and on arrival, settled in to nervously await the next day. Unknown to me I was not alone, as seventeen other young teachers were also beginning their teaching careers at Sale the next day.

Our introduction to teaching was quite perfunctory and most inadequate. On arrival in the Principal’s office we were given a teaching allocation, a time table and a list of Estate Agents. I discovered that I was to teach every year level, including Year 11 and 12 and run the Art Department that the previous Head had left bankrupt. Ridiculous!!! The students arrived back the next day at 9 AM and Term 1 began, despite the record floods that had inundated half the school grounds . In the meantime we had a short Staff Meeting and were then given the afternoon to find somewhere to live, hence the list of Estate Agents.

House hunting began . Armed with our list Karin Frede and I set off. Karin was a German and English first year teacher and fortunately for both of us, our partnership worked very well and we became friends for many years. Unknown to me at this time, a serious young man with a mass of curly dark hair, short pinkish Bermuda shorts, long white socks pulled up the knee and feet clad in Clarks desert boots was also looking for a house. He had chosen as a running mate Paul Ryan, also first year out and a Maths teacher. They had chosen each other on the basis that they both wore Clarks desert boots and that this had to be a good thing. An inspired choice by the four of us, as we all became firm friends, and two marriages also resulted from that chance meeting.

Karin and I found a rather soulless flat in a cream brick veneer block. At the end of Term 1 we moved to a much cosier small workers cottage but we had to get through Term 1 first. That afternoon we signed a lease for the Term, moved in and bought some food. Not much! We mostly ate muesli and waffles for the first month. We didn't have time to cook. There were endless lessons to prepare, correction and interesting boys to meet.

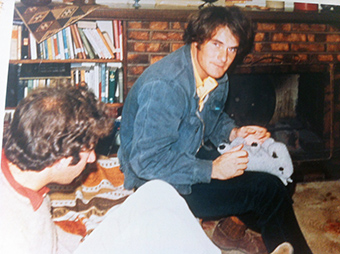

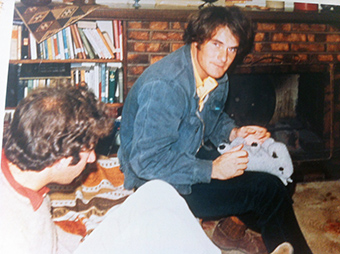

Jono and Paul in Sue and Karin's loungeroom.

From left: Sue, Jono, Libby Taylor and Anne Hayman at Jono and Paul's house

My memories of Sale High School are of fairly harmless country kids, an almost absent Principal and of the power base of the experienced male staff members, known in later years as ‘the boys’. ‘The boys’ resided in a separate staff room, from which came a fog of cigarette smoke, loud male laughter and much footy and cricket talk. A male sanctum, but not for first year male teachers who were not eligible for membership. The rest of us were allocated one of the wooden desks that lined the sides of the small staffroom Tea and coffee making also happened there, right behind my desk.

My desk was next to Mrs Derham’s. She was my confidant and saviour in those hectic first weeks. She was actually quite a lady, probably in her fifties, taught Science, had umpteen children and lived out of town on what was probably a not very profitable farm. She was a very interesting person and it would have been good to know her story as her father was the Chancellor at Melbourne University.

Enough of school, as I can quite honestly say that the highlight was undoubtedly the social life. We first year teachers had a ball. Too busy in the week, but on the weekends we went to the beach, went to the pub, drove to Bairnsdale for Chinese, and had hilarious dinner parties where we played Cludo to all hours. One of the married teachers - he even had children - introduced us to red wine and the art of bottling . This involved a day trip to Chateau Tabilk to buy the bulk wine and a Sunday of bottling. We even had a few trips to Buller and Buchan. Jono Hayman organised one of these trips to the lodge he belonged to at Buller. I was most impressed, and not only by the lodge called Wapiti. The rest is history!!!!

From left Mike Pollack, Margaret, Susan and Rosso hiking at The Cobberas

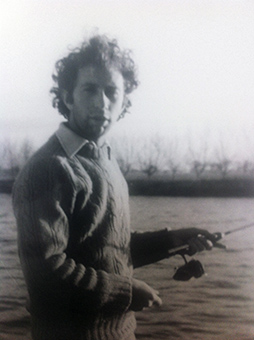

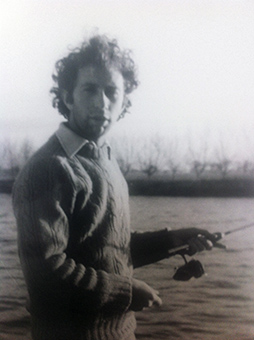

Jono

FIRST YEAR TEACHING AT MOE 1973

Maybe no-one feels in control of their destiny when they’re twenty-one. And maybe everyone thinks they know better than everyone over thirty.

In early February of 1973, I packed my few possessions into my car, picked up Lauren, the only uni friend who had also been appointed to the Latrobe Valley and drove us to Moe Hotel-Motel, where we had booked a room for one night. I had spent a total of six weeks in secondary schools in the previous year. I had taught some very fine lessons, up to two a day, with the class teacher sitting in a back desk. I knew that I disapproved of Skinner and his deterministic attitudes to education. I applauded the free schooling movement in England and America. I was undaunted and full of confidence.

That afternoon I headed up the kilometre or so to the High School. Only Jock, the ancient school cleaner, was there. He pointed me to an empty desk in a staffroom crowded with desks, and advised me, in such strong terms that it has stayed burned into my memory, that I must not let them get away with anything, because all the children were little monsters. I probably smiled indulgently at him. What would he know?

Later that day, Lauren and I visited the flirtatious Moe real estate agent who promised to search out something for us. I don’t know why we thought we could do this at the last moment like that, but by the next day we had signed a lease for a farm house at Hill End, up in the nearby hills. We didn’t even go and look at it.

A few months earlier we studentship holders had filled in a form stating our preferences for our first teaching appointments. But the deal was… you went where you were sent. Moe was only a couple of hours away. I was pretty lucky.

I remember only snatches of the first half year’s classes: Ian Grace nearly strangling a girl with my scarf (don’t ask); loosing my temper with One A, keeping them in at lunchtime and ranting at them, with the sudden revelation that they were sitting in silence because I had told them to; being painfully aware of the Deputy Principal lurking outside my room glaring; teaching Chaucer to the HSC Literature class in the Sixth Form “Common Room”. Gradually I found my feet. I befriended the office staff and the librarian, I explored new ways of bringing the dusty old text books to life, I held my first parent interviews and learnt that the kids liked me.

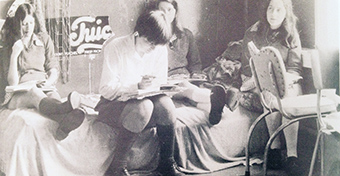

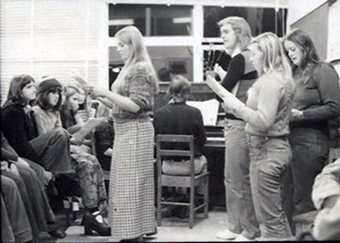

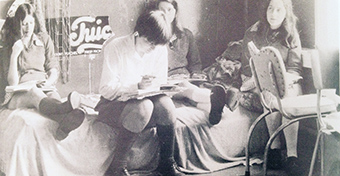

Form Six Lit class in the Common Room

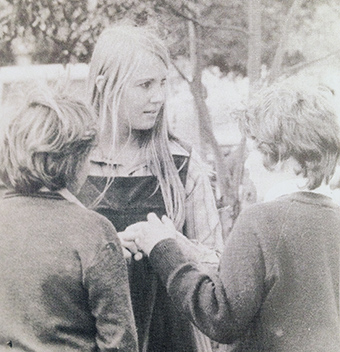

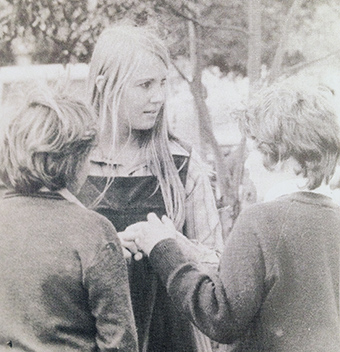

Solving an issue on yard duty

The rhythms of the school year became the rhythms that would govern my life for another thirty-five years.

Within a term I had broken off with my city boyfriend, and began spending weekends with my new colleagues. By mid year, it was clear which of the “first year outs” were only marking time until they could get back to the city. Their cars were always on the road by three thirty on Friday afternoons, while most of us were heading for the pub.

Our home at Hill End was a revelation. Lauren, a country girl, taught me to collect bark to light our wood stove, as we walked over the paddocks. We had a handful of power points, a small LPG gas fridge, a smoky open fire in the small front room, a large country kitchen and a bedroom each. Four rooms. The toilet was at the end of the back garden. The bathroom was a lean-to, where water in a bucket froze in the winter. Our drinking water, which we had to strain for mosquito larvae wrigglers, came from a tank.

The phone, ancient even by 1973 standards, was a wooden box on the wall with a handle to turn. This rang a bell in the Hill End Post Office, where, after a while, the lady would answer, ask which number you would like, and then put you through. And then she listened into your conversation. Maybe she didn’t with anyone else, but we were “the teachers” and we lived in “the teachers’ house”. We were young and interesting: we had parties and men who stayed over.

Our Hill End Phone

Bob, dairy farmer and our landlord, also found us very interesting. We knew that he stood sometimes in the darkness and looked in at us. Bob had been born in our house.His parents had retired to Lakes Entrance, leaving Bob living in the house he had built a hundred meters down the road, with the girl from nearby Trafalgar whom he had married.

Hill End, a tiny dairy farming town, half an hour north of Moe, had a few houses, the General Store/Post Office, a Primary School and the Hall with its tennis courts. The air was clean, the traffic minimal and the pace of life undetectable. On school days we would drive down into the “valley” with its sulphurous yellow smog.

Sometimes, if we left for home after dark, we would find ourselves in dense fog. There were two bridges over the Latrobe River to be navigated before the Hill End Road opened out. One of the bridges was being rebuilt in 1973. What we would now expect to be signposted as “changed road conditions ahead” was a bewildering and ever changing series of by passes. I remember one whited out evening, losing my way, knocking on a door and being confronted by Roxanne Jones from Year 9, whose leering father offered me a bed for the night. That night, and lots of others, I spent in town with friends, making use of the change of clothes I had learned to keep in the boot.

By December I had won most of my battles. “Never smile until Easter” would have been a good idea in hindsight, but, like kids everywhere, most of the Moe kids were forgiving and good natured. Many of them were also poor, needy, abused, illiterate and thirsty for new experiences.

I had joined the Yallourn Madrigal Singers, but every other aspect of my life revolved around the school. We were actively encouraged to try things, to organise and run camps, to start up after-school clubs, to put together musicals, to search out other community members to help, to sponsor, to join in. Before the days of litigation fear, before data collection and evidenced based assessment, before the crowded curriculum.

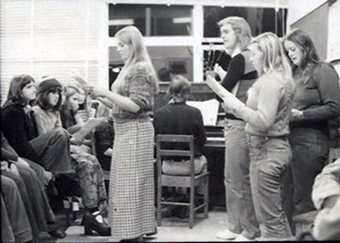

HMS Pinafore rehearsals. The first of over thirty school musicals.

Roger, Deputy Principal and mentor, discussing a Musical Score

I was a more skilled teacher later on. My students wrote better essays, got higher HSC scores, learned self discipline and better manners. But I know that, for all our rawness and lack of experience, we young teachers changed the lives of those 1970s Moe kids.

LIFE OPENS UP AT SALE HIGH SCHOOL 1971

What a learning curve!!! Out in the wide world and what a wonderful world it turned out to be; very scary for a few months but exciting. The scary part was the teaching; the exciting part was the socialising and the ‘abentures.’

Having been granted a studentship I was legally bound to apply for country schools I was more than happy to do so and applied for Mansfield, Alexandra Omeo Corryong etc etc. We had to apply for at least twenty schools and I hoped I would be appointed to one of these most desirable of locations so that I could learn to ski and continue bushwalking. I was appointed to Sale High School and informed in the letter to report at the beginning of Term 1 1971 to Mr A Aitchison, the Principal. Terrifying reality.

I set off the day before the beginning of Term 1, all my possessions crammed into my Hillman Minx, and headed off to a new life and a huge learning curve. I had booked a room at the Midtown Motel in Sale, this in itself a new experience, and on arrival, settled in to nervously await the next day. Unknown to me I was not alone, as seventeen other young teachers were also beginning their teaching careers at Sale the next day.

Our introduction to teaching was quite perfunctory and most inadequate. On arrival in the Principal’s office we were given a teaching allocation, a time table and a list of Estate Agents. I discovered that I was to teach every year level, including Year 11 and 12 and run the Art Department that the previous Head had left bankrupt. Ridiculous!!! The students arrived back the next day at 9 AM and Term 1 began, despite the record floods that had inundated half the school grounds . In the meantime we had a short Staff Meeting and were then given the afternoon to find somewhere to live, hence the list of Estate Agents.

House hunting began . Armed with our list Karin Frede and I set off. Karin was a German and English first year teacher and fortunately for both of us, our partnership worked very well and we became friends for many years. Unknown to me at this time, a serious young man with a mass of curly dark hair, short pinkish Bermuda shorts, long white socks pulled up the knee and feet clad in Clarks desert boots was also looking for a house. He had chosen as a running mate Paul Ryan, also first year out and a Maths teacher. They had chosen each other on the basis that they both wore Clarks desert boots and that this had to be a good thing. An inspired choice by the four of us, as we all became firm friends, and two marriages also resulted from that chance meeting.

Karin and I found a rather soulless flat in a cream brick veneer block. At the end of Term 1 we moved to a much cosier small workers cottage but we had to get through Term 1 first. That afternoon we signed a lease for the Term, moved in and bought some food. Not much! We mostly ate muesli and waffles for the first month. We didn't have time to cook. There were endless lessons to prepare, correction and interesting boys to meet.

Jono and Paul in Sue and Karin's loungeroom.

From left: Sue, Jono, Libby Taylor and Anne Hayman at Jono and Paul's house

My memories of Sale High School are of fairly harmless country kids, an almost absent Principal and of the power base of the experienced male staff members, known in later years as ‘the boys’. ‘The boys’ resided in a separate staff room, from which came a fog of cigarette smoke, loud male laughter and much footy and cricket talk. A male sanctum, but not for first year male teachers who were not eligible for membership. The rest of us were allocated one of the wooden desks that lined the sides of the small staffroom Tea and coffee making also happened there, right behind my desk.

My desk was next to Mrs Derham’s. She was my confidant and saviour in those hectic first weeks. She was actually quite a lady, probably in her fifties, taught Science, had umpteen children and lived out of town on what was probably a not very profitable farm. She was a very interesting person and it would have been good to know her story as her father was the Chancellor at Melbourne University.

Enough of school, as I can quite honestly say that the highlight was undoubtedly the social life. We first year teachers had a ball. Too busy in the week, but on the weekends we went to the beach, went to the pub, drove to Bairnsdale for Chinese, and had hilarious dinner parties where we played Cludo to all hours. One of the married teachers - he even had children - introduced us to red wine and the art of bottling . This involved a day trip to Chateau Tabilk to buy the bulk wine and a Sunday of bottling. We even had a few trips to Buller and Buchan. Jono Hayman organised one of these trips to the lodge he belonged to at Buller. I was most impressed, and not only by the lodge called Wapiti. The rest is history!!!!

From left Mike Pollack, Margaret, Susan and Rosso hiking at The Cobberas

Jono

FIRST YEAR TEACHING AT MOE 1973

Maybe no-one feels in control of their destiny when they’re twenty-one. And maybe everyone thinks they know better than everyone over thirty.

In early February of 1973, I packed my few possessions into my car, picked up Lauren, the only uni friend who had also been appointed to the Latrobe Valley and drove us to Moe Hotel-Motel, where we had booked a room for one night. I had spent a total of six weeks in secondary schools in the previous year. I had taught some very fine lessons, up to two a day, with the class teacher sitting in a back desk. I knew that I disapproved of Skinner and his deterministic attitudes to education. I applauded the free schooling movement in England and America. I was undaunted and full of confidence.

That afternoon I headed up the kilometre or so to the High School. Only Jock, the ancient school cleaner, was there. He pointed me to an empty desk in a staffroom crowded with desks, and advised me, in such strong terms that it has stayed burned into my memory, that I must not let them get away with anything, because all the children were little monsters. I probably smiled indulgently at him. What would he know?

Later that day, Lauren and I visited the flirtatious Moe real estate agent who promised to search out something for us. I don’t know why we thought we could do this at the last moment like that, but by the next day we had signed a lease for a farm house at Hill End, up in the nearby hills. We didn’t even go and look at it.

A few months earlier we studentship holders had filled in a form stating our preferences for our first teaching appointments. But the deal was… you went where you were sent. Moe was only a couple of hours away. I was pretty lucky.

I remember only snatches of the first half year’s classes: Ian Grace nearly strangling a girl with my scarf (don’t ask); loosing my temper with One A, keeping them in at lunchtime and ranting at them, with the sudden revelation that they were sitting in silence because I had told them to; being painfully aware of the Deputy Principal lurking outside my room glaring; teaching Chaucer to the HSC Literature class in the Sixth Form “Common Room”. Gradually I found my feet. I befriended the office staff and the librarian, I explored new ways of bringing the dusty old text books to life, I held my first parent interviews and learnt that the kids liked me.

Form Six Lit class in the Common Room

Solving an issue on yard duty

The rhythms of the school year became the rhythms that would govern my life for another thirty-five years.

Within a term I had broken off with my city boyfriend, and began spending weekends with my new colleagues. By mid year, it was clear which of the “first year outs” were only marking time until they could get back to the city. Their cars were always on the road by three thirty on Friday afternoons, while most of us were heading for the pub.

Our home at Hill End was a revelation. Lauren, a country girl, taught me to collect bark to light our wood stove, as we walked over the paddocks. We had a handful of power points, a small LPG gas fridge, a smoky open fire in the small front room, a large country kitchen and a bedroom each. Four rooms. The toilet was at the end of the back garden. The bathroom was a lean-to, where water in a bucket froze in the winter. Our drinking water, which we had to strain for mosquito larvae wrigglers, came from a tank.

The phone, ancient even by 1973 standards, was a wooden box on the wall with a handle to turn. This rang a bell in the Hill End Post Office, where, after a while, the lady would answer, ask which number you would like, and then put you through. And then she listened into your conversation. Maybe she didn’t with anyone else, but we were “the teachers” and we lived in “the teachers’ house”. We were young and interesting: we had parties and men who stayed over.

Our Hill End Phone

Bob, dairy farmer and our landlord, also found us very interesting. We knew that he stood sometimes in the darkness and looked in at us. Bob had been born in our house.His parents had retired to Lakes Entrance, leaving Bob living in the house he had built a hundred meters down the road, with the girl from nearby Trafalgar whom he had married.

Hill End, a tiny dairy farming town, half an hour north of Moe, had a few houses, the General Store/Post Office, a Primary School and the Hall with its tennis courts. The air was clean, the traffic minimal and the pace of life undetectable. On school days we would drive down into the “valley” with its sulphurous yellow smog.

Sometimes, if we left for home after dark, we would find ourselves in dense fog. There were two bridges over the Latrobe River to be navigated before the Hill End Road opened out. One of the bridges was being rebuilt in 1973. What we would now expect to be signposted as “changed road conditions ahead” was a bewildering and ever changing series of by passes. I remember one whited out evening, losing my way, knocking on a door and being confronted by Roxanne Jones from Year 9, whose leering father offered me a bed for the night. That night, and lots of others, I spent in town with friends, making use of the change of clothes I had learned to keep in the boot.

By December I had won most of my battles. “Never smile until Easter” would have been a good idea in hindsight, but, like kids everywhere, most of the Moe kids were forgiving and good natured. Many of them were also poor, needy, abused, illiterate and thirsty for new experiences.

I had joined the Yallourn Madrigal Singers, but every other aspect of my life revolved around the school. We were actively encouraged to try things, to organise and run camps, to start up after-school clubs, to put together musicals, to search out other community members to help, to sponsor, to join in. Before the days of litigation fear, before data collection and evidenced based assessment, before the crowded curriculum.

HMS Pinafore rehearsals. The first of over thirty school musicals.

Roger, Deputy Principal and mentor, discussing a Musical Score

I was a more skilled teacher later on. My students wrote better essays, got higher HSC scores, learned self discipline and better manners. But I know that, for all our rawness and lack of experience, we young teachers changed the lives of those 1970s Moe kids.

Comments

Twelfth Birthday Letters to Alice

14 10 15 17:07 Filed in: Alice

Letter writing is all but dead. When we were cleaning out our mother’s flat, after she had died, there was a collection of letters received over a lifetime. Love letters from our father, chatty missives from her sister in Sydney, even letters from us as teenagers.

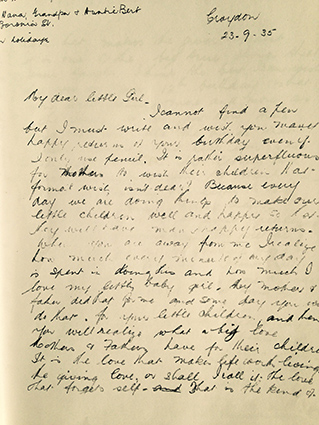

These two letters were written to our mother Alice on her 12th birthday. Alice was staying with her grandparents , Roger and Martha Holm at their house in Boronia Street Surrey Hills. By the way, the house is still there, but more of that later in another story. Living with Roger and Martha was another of their daughters, Bertha or Auntie Bert, unmarried and with a flourishing dressmaking business in the front room of the house. Later she moved the business to Camberwell at the Junction. These letters were written by Alice's father Alfred, usually known as Alf, and her mother Alfreda or Freda. The letters reveal two very different personalities that both had a powerful and enduring influence on their young daughter. Our joint memories of the two authors of the letters are of two very different individuals.

From left Alice, Freda, Marge, Alf

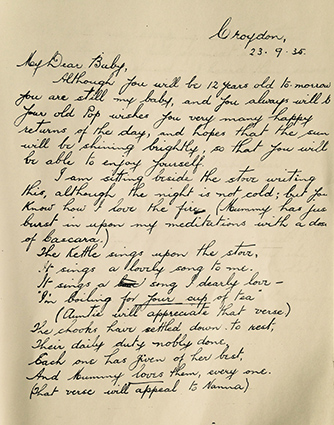

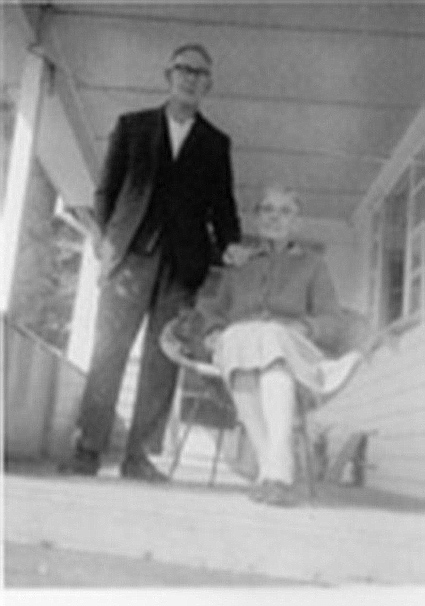

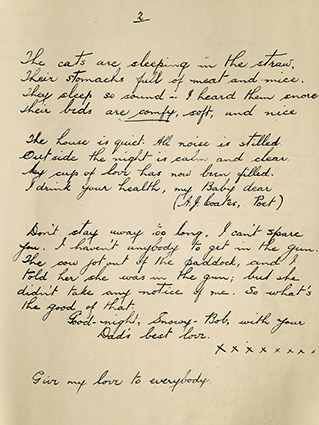

ALF'S LETTER

CROYDON

23.9.35

My Dear Baby,

Although you will be 12 years old tomorrow you are still my baby, and you always will be. Your old Pop wishes you many happy returns of the day, and hopes that the sun will be shining brightly, so that you will be able to enjoy yourself.

I am sitting beside the stove writing this, although the night is not cold; but you know how I love the fire. (Mummy has just burst in on my meditations with a dose of Cascara.) (herbal laxative)

The Kettle sings upon the stove,

It sings a lovely song to me.

It sings a song I dearly love-

“I’m boiling for your cup of tea”

(Auntie will appreciate that verse)

The chooks have settled down to rest

Their daily duty nobly done.

Each one has given of her best,

And Mummy loves them, every one.

(That verse will appeal to Nanna)

The cats are sleeping in the straw,

Their stomachs full of meat and mice.

They sleep so sound - I heard them snore.

Their beds are comfy, soft, and nice.

The house is quiet. All noise is stilled.

Outside the night is calm and clear.

My cup of love has now been filled.

I drink your health, my Baby dear.

(A. J. Coates Poet)

Don’t stay away too long. I can’t spare you. I haven’t any anybody to get in the gun. The cow got out of the paddock, and I told her she was in the gun; but she didn’t take any notice of me. So what’s the good of that.

Good-night, Snowy-Bob, with your

Dad’s best love.

X x x x x x x x

Give my love to everybody.

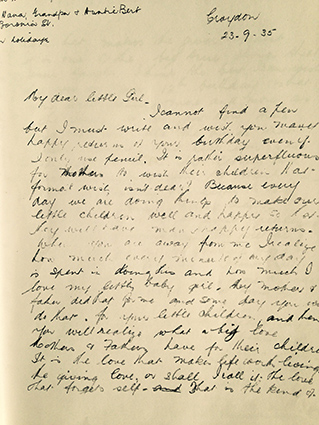

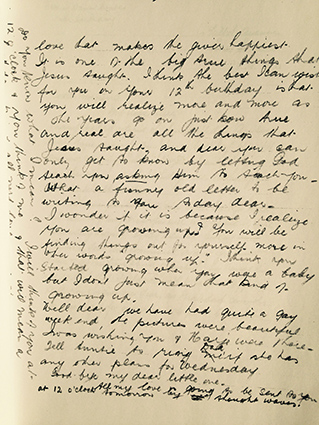

ALFREDA'S LETTER

CROYDON

23.9.35

My dear little Girl,

I cannot find a pen but I must write and wish you many happy returns of your birthday even if I only use pencil. It is rather superfluous for mothers to wish their children that formal wish, isn’t it dear? Because every day we are doing things to make our little children well and happy so that they will have many happy returns.

When you are away from me I realize how much every minute of the day is spent in doing this and how much I love my little baby girl. My mother and father did that for me and some day you will do that for your little children and then you will realise what a big love mothers and fathers have for their children It is the love that makes life worth living - the giving love, or shall I call it: the love that forgets self. That is the kind of love that makes the giver happiest.

It is one of the big true things that Jesus taught. I think the best I can wish for you on your 12th birthday is that you will realize more and more as the years go on just how true and real are all the things that Jesus taught, and dear you can only get to know by letting God teach you, asking Him to teach you.

What a funny old letter to be writing to you today dear.

I wonder if it is because I realize you are growing up. You will be finding things out yourself more, in other words “growing up”. I think you started growing when you were a baby but I don’t just mean that kind of growing up.

Well dear we have had quite a gay weekend, the pictures were beautiful. I was wishing you and Marj were there. Tell Auntie to ring Dad if she has any other plans for Wednesday.

Good-bye my dear little one.

All my love is going to be sent to you at 12 o’clock tomorrow by thought waves.

Do you know what I mean? I will think of you at 12 o’clock and you think of me and that that will mean a birthday kiss and all my love.

Mother

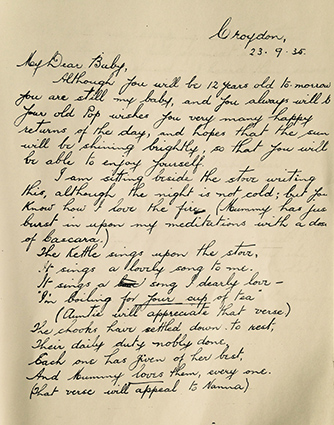

Here are Martha and Roger with Alice and Marge and other younger grandchildren in the Boronia Street Garden

Memories of Alf

“A J Coates, poet.” That dry humour is so much as I remember my papa. My strongest memories of him are from his time living in the flat attached to our house in the nineteen sixties. By that time his red hair was greying and although he was still tall, he was a bit stooped.

“What do an old spud and a man watching a football match have in common? They’re both “specked taters”. His jokes were all like that.

But his sense of humour was strangely coupled with an enduring air of melancholy. He had several “nervous breakdowns” in his life. Nowadays these would be called bouts of clinical depression.

Alf had been a very gifted student and had spent his very early working life as a teacher. The precision of his letter writing is evident in the setting out and punctuation.

We remember his collection of classics and poetry books and often he would lend them to us. He loved reading, including poetry. The “bush poets” Henry Lawson and Banjo Patterson’s best work was behind them by the time Alf was at school, but their work, and that of other Australian poets were very strongly part of the everyday curriculum. This gives a context to Alf writing a mock bush poem as he did in his letter, and signing it like that. But that wry, self deprecating humour is there too.

The other aspect of his personality that shines through is his gentle warmth. This was a time when Australian men were loathe to express such softness. Our mother told us about how he struggled with his own sense of masculinity. Although he worked in timber yards, his work was behind the hardware shop desk. He was ashamed of this. His insistence on only ever wearing black socks was seen as symbolic of his fear of being seen as a sissy. And yet here is this loving, expressive father writing to his daughter, apparently at ease with openly expressing his love.

Memories of Alfreda

Alfreda was also tall. I remember her as a rather elegant, formal figure, clad in beautifully tailored clothes, no doubt made for her by her clever sister. She had very long hair always worn in a loose bun. I do not remember her ever being without her stockings and high heeled lace-up black shoes. The two times I remember staying with Nana and Papa I can remember watching Nana in her dressing gown, sitting at her dressing table, brushing her hair and loosely plaiting it for the night. She was quite a remote figure, not one for hugs and cuddles. However, my memories are of warmth and affection towards her two daughters and her husband.

Neither Margaret or I have any memories of her obviously very strong religious beliefs, that seem to have been very much part of her everyday life and thoughts. We only learnt of these through reading her letters. It would be gratifying to Alfreda that her daughter Alice did indeed see “just how true are all the things that Jesus taught". In fact, in the latter part of her life, Alice’s interest in theology provided her with both intellectual stimulation and solace. I suspect mother and daughter were very alike.

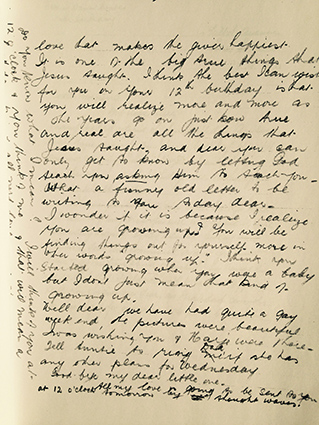

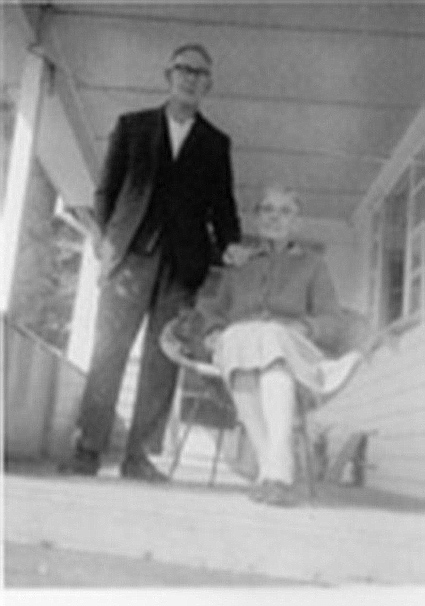

How we remember Alf and Alfreda, in their seventies:

Historical, Social and Geographical context

Main Street Croydon, 1930s

At the time of these letters, the Coates family lived in Hewish Road, Croydon, close to where the Croydon swimming pool is today. The Great Depression of the nineteen-thirties was at its height. Alf never lost his job at the Croydon Timber Yards, even though many men did. The family kept chickens, whose eggs they sold, and a cow and had a large vegetable garden.

Alice and Marge remembered the desperate men who would come to the house for a chance to do some odd jobs around the house. The Coates family were not well off by any means, but they were grateful for what they had and shared it generously with others.

Politically the nineteen-thirties was a time of turmoil and change. Thirty percent of the Australian workforce was unemployed, and this was reflected across the western world. Economic theories about how to deal with the crisis ranged from the Keynesian “spend your way out” adopted by America, to severe austerity and cuts in Government spending practised in Australia. Political “isms” and experimentations like Communism and Nazism were being explored and discussed around kitchen tables everywhere, and nowhere more ardently than at the Coates’. Alice remembered such pearls of wisdom from her mother as “you can’t educate for goodness and you can’t legislate for goodness”.

The young Alice drank in all this talk and even as a twelve year old, when these letters were written, she was developing the philosophies that would engage her for all of her life.

Croydon, a busy suburb nowadays, was a country town, connected by rail to the Eastern suburbs and the city. In 1935 Alice would have been going to Mont Albert Central School (until Year 8) and Marge to the city based Melbourne Girls' High School, soon to be renamed McRobertson Girls' High School. They travelled on the steam train that went as far as Healesville and Warburton. Incredibly this was the closest school for them that went past Year 10. Expensive school fees were a stretch for the family, but education was valued very highly.

These two letters were written to our mother Alice on her 12th birthday. Alice was staying with her grandparents , Roger and Martha Holm at their house in Boronia Street Surrey Hills. By the way, the house is still there, but more of that later in another story. Living with Roger and Martha was another of their daughters, Bertha or Auntie Bert, unmarried and with a flourishing dressmaking business in the front room of the house. Later she moved the business to Camberwell at the Junction. These letters were written by Alice's father Alfred, usually known as Alf, and her mother Alfreda or Freda. The letters reveal two very different personalities that both had a powerful and enduring influence on their young daughter. Our joint memories of the two authors of the letters are of two very different individuals.

From left Alice, Freda, Marge, Alf

ALF'S LETTER

CROYDON

23.9.35

My Dear Baby,

Although you will be 12 years old tomorrow you are still my baby, and you always will be. Your old Pop wishes you many happy returns of the day, and hopes that the sun will be shining brightly, so that you will be able to enjoy yourself.

I am sitting beside the stove writing this, although the night is not cold; but you know how I love the fire. (Mummy has just burst in on my meditations with a dose of Cascara.) (herbal laxative)

The Kettle sings upon the stove,

It sings a lovely song to me.

It sings a song I dearly love-

“I’m boiling for your cup of tea”

(Auntie will appreciate that verse)

The chooks have settled down to rest

Their daily duty nobly done.

Each one has given of her best,

And Mummy loves them, every one.

(That verse will appeal to Nanna)

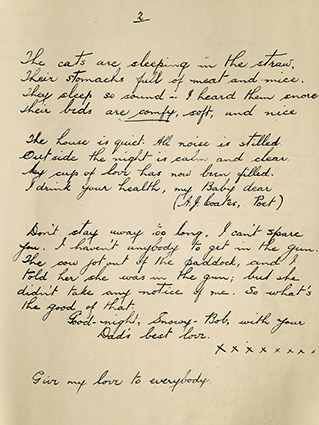

The cats are sleeping in the straw,

Their stomachs full of meat and mice.

They sleep so sound - I heard them snore.

Their beds are comfy, soft, and nice.

The house is quiet. All noise is stilled.

Outside the night is calm and clear.

My cup of love has now been filled.

I drink your health, my Baby dear.

(A. J. Coates Poet)

Don’t stay away too long. I can’t spare you. I haven’t any anybody to get in the gun. The cow got out of the paddock, and I told her she was in the gun; but she didn’t take any notice of me. So what’s the good of that.

Good-night, Snowy-Bob, with your

Dad’s best love.

X x x x x x x x

Give my love to everybody.

ALFREDA'S LETTER

CROYDON

23.9.35

My dear little Girl,

I cannot find a pen but I must write and wish you many happy returns of your birthday even if I only use pencil. It is rather superfluous for mothers to wish their children that formal wish, isn’t it dear? Because every day we are doing things to make our little children well and happy so that they will have many happy returns.

When you are away from me I realize how much every minute of the day is spent in doing this and how much I love my little baby girl. My mother and father did that for me and some day you will do that for your little children and then you will realise what a big love mothers and fathers have for their children It is the love that makes life worth living - the giving love, or shall I call it: the love that forgets self. That is the kind of love that makes the giver happiest.

It is one of the big true things that Jesus taught. I think the best I can wish for you on your 12th birthday is that you will realize more and more as the years go on just how true and real are all the things that Jesus taught, and dear you can only get to know by letting God teach you, asking Him to teach you.

What a funny old letter to be writing to you today dear.

I wonder if it is because I realize you are growing up. You will be finding things out yourself more, in other words “growing up”. I think you started growing when you were a baby but I don’t just mean that kind of growing up.

Well dear we have had quite a gay weekend, the pictures were beautiful. I was wishing you and Marj were there. Tell Auntie to ring Dad if she has any other plans for Wednesday.

Good-bye my dear little one.

All my love is going to be sent to you at 12 o’clock tomorrow by thought waves.

Do you know what I mean? I will think of you at 12 o’clock and you think of me and that that will mean a birthday kiss and all my love.

Mother

Here are Martha and Roger with Alice and Marge and other younger grandchildren in the Boronia Street Garden

Memories of Alf

“A J Coates, poet.” That dry humour is so much as I remember my papa. My strongest memories of him are from his time living in the flat attached to our house in the nineteen sixties. By that time his red hair was greying and although he was still tall, he was a bit stooped.

“What do an old spud and a man watching a football match have in common? They’re both “specked taters”. His jokes were all like that.

But his sense of humour was strangely coupled with an enduring air of melancholy. He had several “nervous breakdowns” in his life. Nowadays these would be called bouts of clinical depression.

Alf had been a very gifted student and had spent his very early working life as a teacher. The precision of his letter writing is evident in the setting out and punctuation.

We remember his collection of classics and poetry books and often he would lend them to us. He loved reading, including poetry. The “bush poets” Henry Lawson and Banjo Patterson’s best work was behind them by the time Alf was at school, but their work, and that of other Australian poets were very strongly part of the everyday curriculum. This gives a context to Alf writing a mock bush poem as he did in his letter, and signing it like that. But that wry, self deprecating humour is there too.

The other aspect of his personality that shines through is his gentle warmth. This was a time when Australian men were loathe to express such softness. Our mother told us about how he struggled with his own sense of masculinity. Although he worked in timber yards, his work was behind the hardware shop desk. He was ashamed of this. His insistence on only ever wearing black socks was seen as symbolic of his fear of being seen as a sissy. And yet here is this loving, expressive father writing to his daughter, apparently at ease with openly expressing his love.

Memories of Alfreda

Alfreda was also tall. I remember her as a rather elegant, formal figure, clad in beautifully tailored clothes, no doubt made for her by her clever sister. She had very long hair always worn in a loose bun. I do not remember her ever being without her stockings and high heeled lace-up black shoes. The two times I remember staying with Nana and Papa I can remember watching Nana in her dressing gown, sitting at her dressing table, brushing her hair and loosely plaiting it for the night. She was quite a remote figure, not one for hugs and cuddles. However, my memories are of warmth and affection towards her two daughters and her husband.

Neither Margaret or I have any memories of her obviously very strong religious beliefs, that seem to have been very much part of her everyday life and thoughts. We only learnt of these through reading her letters. It would be gratifying to Alfreda that her daughter Alice did indeed see “just how true are all the things that Jesus taught". In fact, in the latter part of her life, Alice’s interest in theology provided her with both intellectual stimulation and solace. I suspect mother and daughter were very alike.

How we remember Alf and Alfreda, in their seventies:

Historical, Social and Geographical context

Main Street Croydon, 1930s

At the time of these letters, the Coates family lived in Hewish Road, Croydon, close to where the Croydon swimming pool is today. The Great Depression of the nineteen-thirties was at its height. Alf never lost his job at the Croydon Timber Yards, even though many men did. The family kept chickens, whose eggs they sold, and a cow and had a large vegetable garden.

Alice and Marge remembered the desperate men who would come to the house for a chance to do some odd jobs around the house. The Coates family were not well off by any means, but they were grateful for what they had and shared it generously with others.

Politically the nineteen-thirties was a time of turmoil and change. Thirty percent of the Australian workforce was unemployed, and this was reflected across the western world. Economic theories about how to deal with the crisis ranged from the Keynesian “spend your way out” adopted by America, to severe austerity and cuts in Government spending practised in Australia. Political “isms” and experimentations like Communism and Nazism were being explored and discussed around kitchen tables everywhere, and nowhere more ardently than at the Coates’. Alice remembered such pearls of wisdom from her mother as “you can’t educate for goodness and you can’t legislate for goodness”.

The young Alice drank in all this talk and even as a twelve year old, when these letters were written, she was developing the philosophies that would engage her for all of her life.

Croydon, a busy suburb nowadays, was a country town, connected by rail to the Eastern suburbs and the city. In 1935 Alice would have been going to Mont Albert Central School (until Year 8) and Marge to the city based Melbourne Girls' High School, soon to be renamed McRobertson Girls' High School. They travelled on the steam train that went as far as Healesville and Warburton. Incredibly this was the closest school for them that went past Year 10. Expensive school fees were a stretch for the family, but education was valued very highly.