Fire and Storm

MY COUNTRY By Dorothy MacKellar

‘I love a sunburnt country,

A land of sweeping plains,

Of ragged mountain ranges,

Of droughts and flooding rains.

I love her far horizons,

I love her jewel sea.

Her beauty and her terror,

The wide brown land for me.

Margaret and I learnt this iconic poem during our respective Grade 6 years and many of its lines are still etched in memory. In fact we can still recite much of it with exactly the same intonation and expression. This poem, written in 1904, captures the tenor of our post, Fire and Storm.

Fire, still very much part of our lives, has also been part of our family history.

BLACK THURSDAY 1851

The first reference to fire was in1851 with the fire known as ‘Black Thursday’.

Painting by William Strutt

This was the first catastrophic bushfire faced by white settlers in Victoria. The lead up to the fire followed what is now a familiar pattern of events. Reports at the time said that there had been wet years of lush growth followed by severe drought, leaving the bush and long grass tinder dry. Thursday the 6th of February dawned hot and windy, and the fires took off, leaving one quarter of the state black and smouldering. Our antecedents, the Bourke’s of Pakenham, were caught up in the fires in a dramatic way. Shortly before Black Thursday the Bourke’s had taken possession of Bourke’s Hotel in Pakenham. Michael Bourke remained at their selection, while Mrs Bourke was to run the hotel and Post Office.

‘On Black Thursday the whole district was ablaze. Mr Bourke was trying hard to save the station property. Water having been exhausted, milk was brought into play and ultimately the run was saved. Word was brought to him that the hotel property at Pakenham was surrounded by fire. Galloping down there, he found his wife and her children had saved themselves by crouching in the water in the bed of the creek.’

We took this photo of the exact spot, during our visit to Pakenham.

BACCHUS MARSH FIRE 1928

From an article in ‘The Argus' Thurs 12th July 1928

"FIRE AT BACCHUS MARSH.THREE SHOPS DESTROYED"

This was a report on the fire suffered by our grand parents, Alf and Alfreda, in which they lost almost everything, but escaped with their lives. We heard dramatic stories of this fire in childhood and is told below by Marge and Alice on the tape they made in 1990.

The hardware shop was their business, and they had gone out on their own, in an already a difficult time of their lives. Aunty Bert was staying with them to help out, as was her role in the family, as the unmarried sister. Auntie Bert, Alf and Alfreda would have been in their early thirties,Alice was five and Marge three years older. Thank goodness Bert was there as she seems to have had a cool head and took action to get everyone out as the fire took hold.

Marge and Alice’s recollection is fairly accurate, as the newspaper report comments on the strong North wind and the poor water pressure that hampered the fire fighting.

The Argus reports that at one stage,

…. the premises of Mr. G. H. Anderson were threatened , but this danger passed, with a change in the direction of the wind, A good portion of the stocks of Messrs. McLaren and Coates was saved, but considerable damage was done to Mr. Phillip’s stock. It is understood that all buildings and stock, except that of Mr. McLaren, were insured.

At half-past 7 o'clock, in the morning the fire was under control, and all that was left of three of the shops were the walls.’

Mr McLaren may have been uninsured but Alf was definitely not, as he had been unable to pay the insurance. They lost nearly everything.

We had wondered about Alice’s comment about Auntie Bert’s friend Nell Pearce, whose family took them all in after the fire, and yes it was a large and impressive brick house, still standing today:

As Alice states the Pearces were an influential family in the town. They had been an early pioneering family in the area. They built and established the General Store that presumably was very profitable, supplying the miners on the way to the Goldfields as well as the local community. The family then went into farming and other small businesses, and were influential in civic affairs.

Auntie Bert maintained a lifelong friendship with Nell, and neither of them married. I remember Nell Pearce being a name mentioned in conversation and I have a vague recollection of her as an imposing figure. I also remember her at Auntie Bert’ s sewing rooms in Camberwell. She was probably there for a fitting. Little did we know the history behind that friendship.

After cleaning up and sorting our their affairs Alf and Alfreda, the girls and presumably Auntie Bert left Bacchus Marsh and stayed with Grandpa and Grandma Holm in Surrey Hills. Alf then got a job in Croydon as manager of the hardware shop, where they spent many happy years.

BLACK FRIDAY 1939

After the 1851 fires, bush fires occurred in many parts of the State with predictable monotony. The next major statewide fire was in 1939, once again after a prolonged drought. High temperatures and strong northerly winds fanned separate fires that eventually combined and created a massive fire front that swept mainly over the mountain country in the northeast of Victoria, and along the coast in the southwest.

Lilydale Brigade 1939.

Source - CFA Website

More than two million hectares were burnt in the 1939 fires.They lasted for a week. Many, unable to be controlled, were left to burn out.

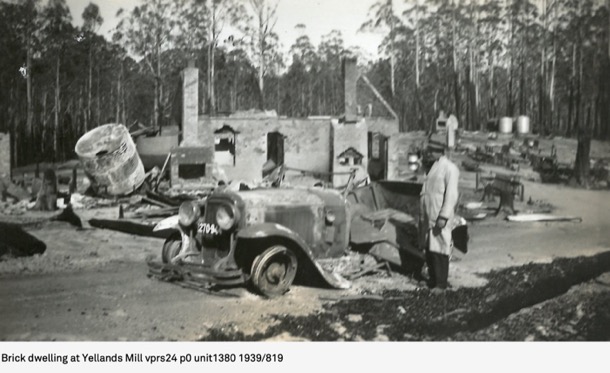

Yellands Mill, where 15 men died:

The extensive damage to over two million hectares of farmland and forest, not to mention the loss of livestock and lives, prompted a Royal Commission. They were tasked with examining the causes of the fire and making recommendations for future management.

The Royal Commission’s specific recommendation was that the various Bush Brigades, and Country Fire Brigades be amalgamated to form a single organisation to fight fire on private land outside the Metropolitan Area. The Forest Commission was responsible for fire on public land and the Metropolitan Fire Brigade was responsible for fire in the Metropolitan Area. Instead of a myriad of uncoordinated small brigades these three organisations were responsible for fighting fires in Victoria.

EARLY BUSHFIRE EXPERIENCE - MARGARET

My first memory of wildfire is of a fire on the empty block next door. The vegetation was sparse: weeds and gorse, with patches of bare clay.

We think it was around 1955. Sue doesn’t remember it, and was probably at school. But I have a clear memory and so I was probably at least four. The image in my mind is of mum, armed with a hessian bag, beating flames. Hessian is a coarse, rough brown fabric made from jute, widely used for packaging. We had a supply of hessian bags, saved from buying bulk chook food. Mum was not a “bush woman” in the Henry Lawson image, but she would have seen this form of fire fighting, and she apparently felt able to take it on.

Fire fighting with a hessian bag.

I don’t remember bush fires being a big part of my life as a child, until I was eleven, in 1962. That year was a big bushfire year in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs: 32 people died and 450 houses were lost. Areas affected included Mitcham, less than ten kilometres away from our place. We were never in danger in suburban Box Hill South, but there would have been a red glow in the sky, and the vivid memory I have of burning gum leaves falling in the back yard, is probably from this fire.

In 1979, I moved to the Dandenong Ranges, where the CFA had much more of a presence, and bushfire awareness was part of everyday life over Summer.

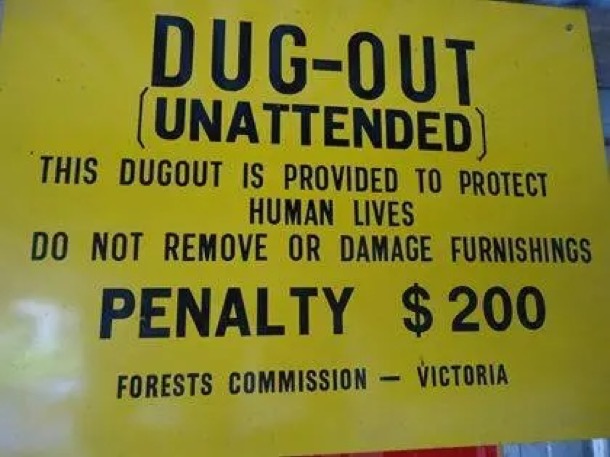

In those first few years, there was still on old dugout just over the road in the forest. It had a wooden sign “Dugout” and what looked like a large wombat hole. A closer look revealed a heavy grey army blanket hanging over the entrance. During a fire, this would be kept wet. Inside was a rounded cave, with earthen floor, ceiling and walls. It would have held a maximum of six adults. There was a metal bucket and a pile of musty grey wooden blankets. I guess it might keep you safe while a canopy fire raced overhead, but I wouldn’t want to rely on it.

The CFA were, and still are, omnipresent. On weekends they collect donations at major intersections. On Good Friday, and in the week before Christmas, they drive through the streets, playing piped music and rattling collection tins. Their sirens regularly echo through the Hills. We can hear the Belgrave, Upwey and Kallista sirens from our place, and sometimes all three will go off. In the past, the siren was used to call in the volunteers, and on a set night of the week, on CFA practice night, they would test the siren at a set time. We like that the sirens are still used, not so much as a specific warning, but as part of our aural landscape.

Nowadays, when we hear a siren, we go straight to the Victorian Emergency app, to check what has happened. Often it’s a house fire, a car accident, a small bush fire. During the Summer months we are more attuned to the sound. Our practice has long been to evacuate on days of dangerous fire weather.

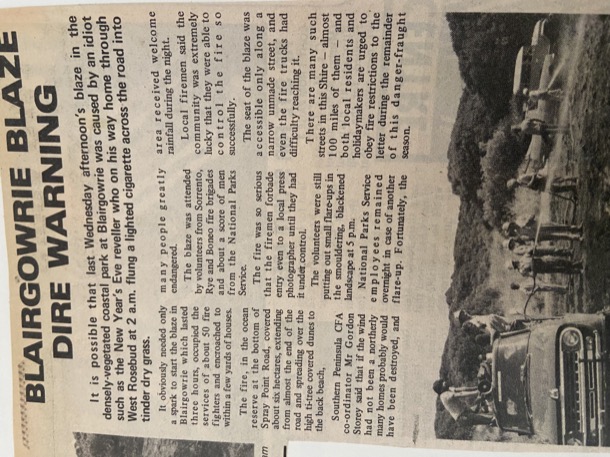

BLAIRGOWRIE FIRE 1980 - SUE

My only experience of fire first hand, was in 1980 at Janey’s house at Blairgowrie. We had all just sat down to lunch. Anna was nearly three and I was pregnant with Thomas. Everything was tinder dry, as it was January and we were in the middle of the 1979-1983 Eastern Australian Drought.

Halfway through lunch there were loud knocks at the door, and a panicking young man asked us for a hose, as he has seen a small fire beginning to build on the Spray Point Road, just fifty metres from the house. Jono and Janey raced down to investigate, but realised that they had not a chance of stopping the fire. It was spreading quickly, fanned by a strong north wind. This was a stroke of luck as this meant it was spreading away from us and towards the beach. We called the CFA who responded promptly, parking several fire trucks at the hydrant on the nature strip.

We were told to block the downpipes with oranges, fill the gutters with water, and shelter inside. The fire was brought under control fairly quickly but not before six hectares of the National Park was burnt.

It would have been a different story if the wind had changed and pushed the fire towards Janey’s house and of course all the other houses.

Local newspapers at the time reported on the fire and issued warnings and advice to residents and holiday makers for the rest of the holiday season that was only just beginning.

ASH WEDNESDAY

SUE

On Ash Wednesday I was at home with Thomas, as Anna had just started school. Thomas was happily playing with water in the shade of our pergola, as it was a very hot day. A nasty north wind intensified as the day wore on and many fires started across Victoria. I was listening to the ABC afternoon show hosted by Tony Delroy, who, as fires broke out, was reporting the outbreaks in real time. He also took many calls from people desperate for information. There were no centralised communications hub, warning system, or, of course, mobile phones. As the fires continued to burn during the evening and that night, the radio was the only source of state wide information. The 3LO radio hosts worked on a roster system to get the information out.

Since its inception the ABC had been responsible for emergency broadcasting, but only on the news bulletins.. In 1997 Ian Mannix was appointed as Program Director for Local Radio Victoria. He changed the nature of emergency broadcasting during the 1997 bush fire in the Dandenong Ranges. The fires burnt for days, three people died and forty homes were destroyed. Mannix asked the CFA for advice on what to say to to listeners ‘who were confronted with flames.’…Interestingly, the CFA had no experience of giving warnings and had never written a warning for people at risk.

Mannix went ahead and took the lead in creating the ABC’s approach to emergency broadcasting. He developed guidelines that included warnings at set intervals, including bush fire alerts for low level fires and urgent threat warnings for more serious fires. The system used in Victoria was expanded nationally after Black Saturday in 2009. Further recommendations were made by the Black Saturday Royal Commission that future refined and expanded the warning systems to television and commercial radio.

From this pioneering work by Ian Mannix, we now have an Australia wide warning system, and broadcasting training and guidelines in each state.

Ian Mannix oversaw the development and implementation of these systems and deservedly received the Australian Public Service Medal in 2012.

MARGARET

The first actual fire we had to deal with in Belgrave was the 1983 Ash Wednesday.

The name “Ash Wednesday” is nothing to do with ash from bushfires. It’s a historical/religious reference. It happens every year, and it marks the beginning of Lent, leading up to Easter, in lots of Christian denominations. It follows Shrove Tuesday, Mardi Gras … the last day of feasting before the deprivations of Lent. The ‘ash’ is sprinkled onto heads or swiped across foreheads as part of the Ash Wednesday service.

1982 had had a very droughty Winter, Spring and Summer. The little creek that runs through the forest over the road had almost stopped, and underfoot the leaves crackled.

The 1983 Melbourne dust storm, when 50,000 tonnes of Mallee topsoil turned the sky dark brown across the city, happened in early February. For me, it hit as I was crossing Burwood Highway on my way to the Ferntree Gully hotel, for an after school cool drink. The dust cloud was over 300 metres high and 500 kilometres long, and darkened the sky for an hour. It’s one of those iconic events where everyone can tell you where they were when it hit.

Image credit: Katsuhiro Abe/BOM

There were many fires that Summer. The CFA across Victoria attended nearly 3,200 fires. Wednesday February 16th was particularly hot and windy.

That morning I had woken feeling nauseous and weak. I rang in sick, and went back to bed. Within a few weeks, I would find out that this had been the beginning of morning sickness. Michael was born that October.

Later in the day I had a phone call from a friend who lived locally, suggesting I might consider leaving, as he had heard there was a fire in Belgrave Heights. Outside was stifling. My neighbour was packing her car but she was expecting to wait and see. I don’t remember having any sense of danger, though, later, we learnt that it was only the late afternoon wind change that stopped the fire from sweeping through Belgrave township and on to our place.

Photo: Tonia Van der Dungen. Christmas Hills CFA

Wind changes during bush fires dramatically widen the fire front, and this one swept through Belgrave South and on to Cockatoo and Upper Beaconsfield.

I don’t remember this, but apparently Ian and Lois were visiting me that day. Lois was pregnant with Sam who was born that winter. Ian speaks of driving home in the afternoon, and taking the sudden decision to drive straight on through Belgrave, rather than the more logical route through to Belgrave South. This would have been exactly the time of day when the fire swept through across the road they would have been on.

Later there were many stories, horrifying and heroic. In Cockatoo, 300 people sheltered during the night in the kindergarten, as a handful of local men kept the flames and embers at bay, saving many lives.

Across Victoria, 75 people died, more than 200,00 hectares were burnt and 2000 homes and buildings were damaged.

Friends from the suburbs rang to check that I was ok. Our little patch of the Dandenongs was untouched, but one didn’t have to drive very far to see the black horror.

Photo: Critchley Parker Junior Reserve. Upper Beaconsfield CFA

Ten years later, I began teaching at Monbulk College, and some of our students were still affected by their experiences in 1983. My friend and colleague Sarah had her Year 8 English class make a booklet marking the ten year anniversary. Everyone had stories, which the students typed up and put together. It remains an important part of the history of Dandenong Ranges, and other affected parts of Victoria.

The tragic Ash Wednesday fires were like those of 1939 Black Friday in intensity, if not in range. They confronted the modern firefighting community with the limits of its capacity and technology. Among the 75 dead, 17 firefighters died that day, some of them next to their well equipped tankers on a forest road in Upper Beaconsfield, when the wind changed and the firestorm swept over them. Changes in firefighting strategies and philosophies were inevitable. The community needed to be better informed and more involved. This is certainly my experience. I was so naive and ignorant, compared to what we expect from Hills people nowadays! There was a huge Royal Commission.

It seemed, as the Commission heard people’s Ash Wednesday stories, that the most dangerous situations people faced were from hurried departures. People died in their cars, not their homes. But the CFA could not guarantee to be there during huge bush fires, protecting every home.

And then there were stories of people actively defending their homes from ember attacks, and saving them. “People save houses. Houses save people.” was the mantra.

The “stay or go” policy began to be developed. As the professionalisation of firefighting, and the ‘Science’ of fire behaviour developed, ordinary people’s anecdotes were often disregarded as over hyped and hysterical.

There was a huge campaign to teach the population about how to prepare their homes, and defend them. Because it was so centralised, the people who lived on the edges of grasslands and those, like us, in what nowadays we call the “flame zone”, were given the same advice. The “go” part of “stay or go” felt like an afterthought for people who were not able bodied. I remember some of our neighbours’ plans were that the men and older boys would “stay” and the women and little children would “go”.

In 1987 the very first General Achievement Test had as one of its tasks information about how to prepare a home for bushfire. It was clearly in the zeitgeist.

My personal experience of this policy is encapsulated by a CFA Fireguard group meeting, in the years leading up to 2010, that we attended on our neighbour’s verandah. The CFA man explained patiently about how bushfires behave, and how we should be preparing our houses, so that we could defend them. The expectation was clearly that we and our neighbours would stay, in the case of a bushfire, and, with mops and buckets of water, we would put out any embers that threatened out house. We pointed to the towering ash forest, metres from our house, and told him we didn’t think our house would be defendable. He was not impressed.

Throughout the Millennial drought, from 1997 to 2009, during the most severe summers, we kept a trailer full of things at Chris’s parents’ place, and had a very clear plan. We evacuated quite a number of times, staying in their spare room. The plan was to insure fully, and simply not to be there during dangerous times. The local schools built fire refuges, and the CFA kept on with its “stay and defend” message. Water saving advice was everywhere. Like many others, we set up a grey water system to water our garden.

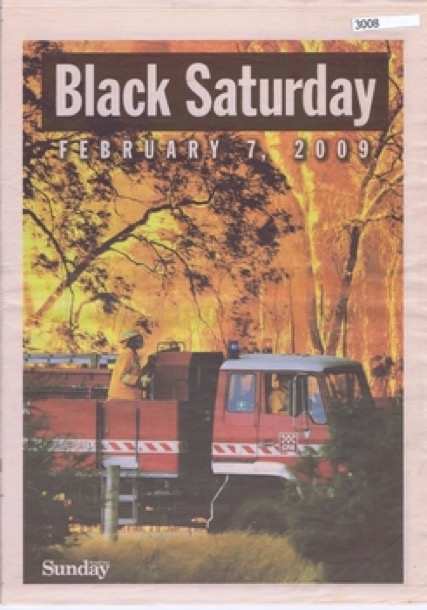

BLACK SATURDAY - MARGARET

And then came the summer of 2008-9. It had been particularly dry and hot. This was the summer when tree fern fronds were scorched, lawns died and record high temperatures were broken day after day. The forecast for the first week of February looked horrendous in advance, with temperatures of 48 degrees forecast, and Chris and I decided to take ourselves camping by the Thurra river, and wait it out. I was glad to be retired by then!

We followed the news of Black Saturday, on the radio, and, once the cool change hit, we packed up and drove out along the Thurra Road, as news of the death toll mounted. Along the Princes Highway, we saw fire fighters’ camp sites with row after row of little tents. The air was smokey, and through the Latrobe Valley we drove through a blackened landscape. At home, the garden was scorched and everything still crackled underfoot.

Back with television coverage, we watched interviews with people who had miraculously survived, saw footage of people’s fire refuges that had been easily breached, and heard the stories of person after person, traumatised by their unsuccessful attempts to defend their homes. 173 people had died, 120 of them in the Kinglake area. More than 450 hectares had burned and 3500 buildings, 200 of them houses, had been destroyed.

Herald-Sun

That cool change was not the end of the 2009 fire season. We evacuated a number of times that February. One day, a fire bug lit a fire just up the hill from us. I was sitting outside, and heard the crackle as flames licked up a nearby gum tree. Chris was walking in the forest. As I drove down to the Belgrave carpark, he was walking quickly back down through the forest, having seen the smoke. When he met a wall of flames, he backtracked hastily, headed toward the road, and hitched a ride with a stranger to near home. The wind was blowing the danger away from our place. I have been mocked mercilessly for my paper post it note on the door telling him I’d gone to the Belgrave car park, but at least he knew that I was out of danger.

In the car park, a gaggle of us watched the Elvis fire bombing helicopters head up the hill, and cheered, and very soon the whole drama was over.

2009 marked the end of the Millennial drought years. Summers since then have been cooler and wetter. But the legacy has been an obsession with rainfall figures, forecasts and climate outlooks.

Our local community facebook page has a member who is a forecaster with the Bureau of Meteorology, who posts every time there is a weather anomaly. It is clear from the responses to him, that we are not alone in our anxiety about rainfall.

THE BIG STORM - MARGARET

It was winter, 2021. There had been yet another Covid lockdown, this one lasting two weeks, finishing on June 10th. Life quickly went back to normal for most people in Melbourne.

But for us in the Dandenongs, the evening of June 9th, and the next morning, brought a massive windstorm which brought down huge swathes of trees, many across roads and onto 112 houses. The wind came at 120kph, but it came from an unusual direction, and our shallow rooted mountain trees were largely untested from that direction. They fell, roots and all, in their hundreds.

Even though the power went off immediately, and all the mobile towers were out, there were 9,500 calls for help logged by the SES. People were trapped in their houses, and many streets, including Michael and Katherine’s were blocked off. There was no way of communicating, in or out, for many days.

My most vivid memory of the storm comes from early on the morning of the tenth. Chris was standing with a view to the north of the forest out the window. His eyes widened, and yet another a great crash came from the forest. He had watched a two hundred foot tall mountain ash eucalypt gracefully fall sideways, taking down another tree of similar size, which in turn took out another one. Like enormous dominos, the three of them had joined the huge pile of previous victims on the forest floor. Later on we stood on the road, looking down where they had fallen and counted thirteen giant trees lying in a messy tangle.

Elsewhere in the Hills, this carnage had been repeated in town after town. We lucky ones who still had homes, watched with dismay as the power company’s estimates of power restoration stretched out beyond a week. Eventually we were able to drive out. It was a weird feeling to drive down onto the flat and find life going on as normal. For us the feeling was very much as if we were still in lockdown. On the Monday evening, I went to choir rehearsal in Ferntree Gully, blinking in the unaccustomed bright lights. Many of us Hills residents had brought items to be recharged during the evening. At end of the night we drove back up into the darkened Hills.

At home, we went into camping mode. There was no hot water, but we had plenty of fire wood, and our very effective wood heater. We cooked with gas and our little portable gas fridge kept our essentials cold. I took to having my bucket bath in the afternoon, when it wasn’t quite so cold in the bathroom. It was ten days before our power came back on, on June 20th.

The reprieve from lockdown lasted only a month. By July 16, Melbourne was back into working from home, home schooling, and leaving home only for essential purposes.