Books of Our Childhood

18 09 24 13:00 Filed in: Children 1950s

Books have always played a large part in our lives and I cannot remember a time when we have not had a book ‘on the go’. As children we grew up with books in the house. Our parents read at night when we had gone to bed.

We are three years apart, and our early childhood experiences are quite different. Despite the three year gap, when we read lists of books for little children, from those times, the same titles resonate for both of us.

As we became independent readers, home time meant being left much of the time to our own devices. The municipal library was our source of escapism, adventure and vicarious happiness.

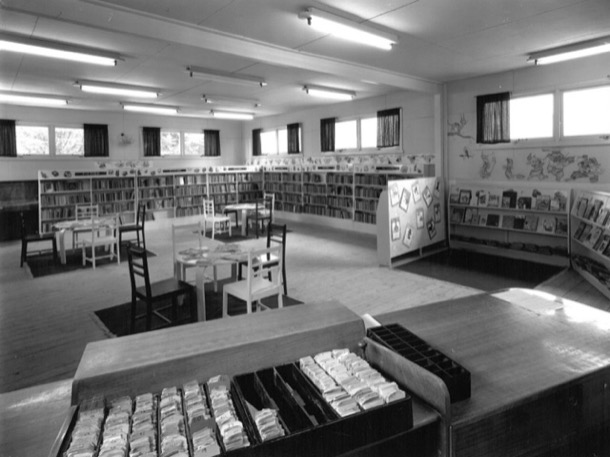

I vividly remember what I assume was a private, lending library coming to the house with blue covered hard back books for Mum and Dad to borrow. I remember the small van parked at the front door and the gentleman, clad in a fawn dust coat, bringing in the books and inserting the borrowing card in the pocket inside the back cover of items borrowed. We cannot find any reference to travelling lending libraries but we surmise that it may have been an offshoot of a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens. Public lending libraries were not established until the 1960s, in response to public pressure. Maybe when Mum and Dad lived with her parents they had all belonged to a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens, not far from Boronia Street, where they lived.

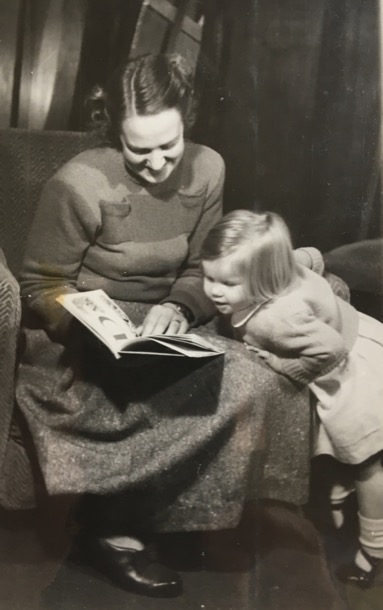

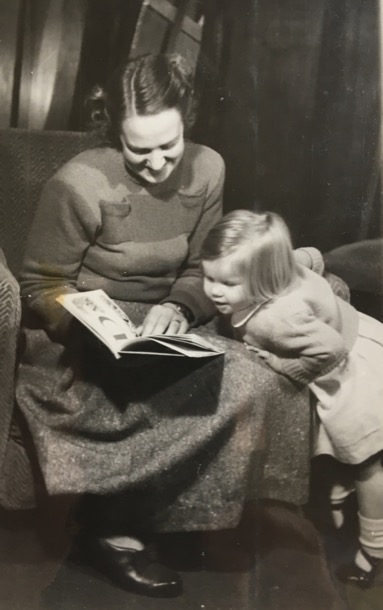

I loved having Mum read to me.

But Margaret was three years younger and her experience was completely different:

“I was just three when the next baby in line was born. He was premature and challenging, and we think our mother probably found the next few years a very difficult time.

In the years before he was born, she read to Sue, and I was there, but I don’t have much memory of it. I certainly don’t have the strong, warm connection to those books that Sue has. And when I was of an age where they would have been appropriate for me, Mum was caught up with managing the baby, and I was pretty much left to my own devices.

I remember, later on, her reading to our two younger brothers, perhaps when they were about three and five years old. But, by then I was reading for myself.”

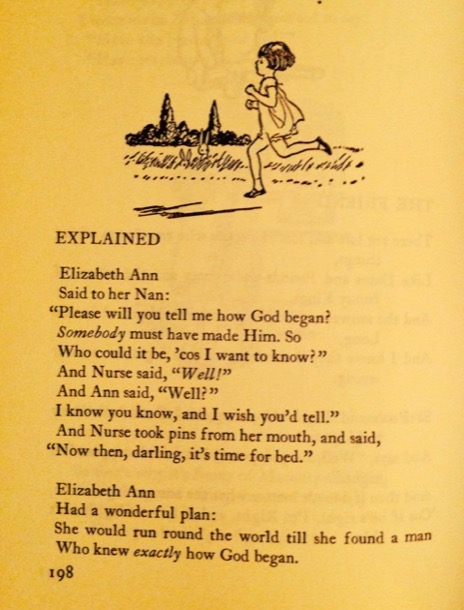

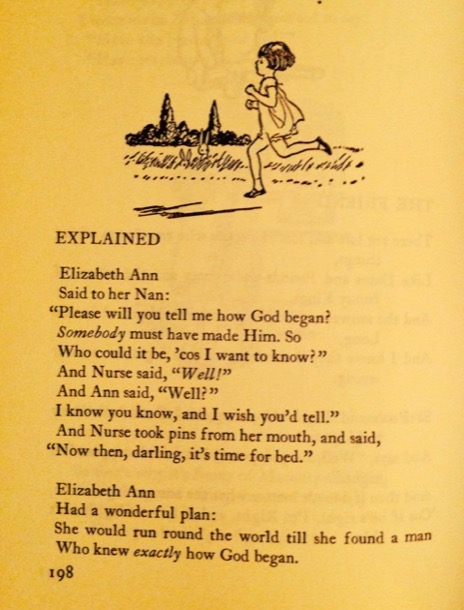

One of my earliest memories was of the A.A. Milne books. Milne wrote the story of Winnie-the-Pooh for his son, on whom the character of Christoper Robin was based.

We also had a vinyl record of the poems read by a man, with a very English accent of course. We must have listened to it hundreds of times, as Margaret and I can both recite The King’s Breakfast and some others, with exactly the same rhythm and expression.

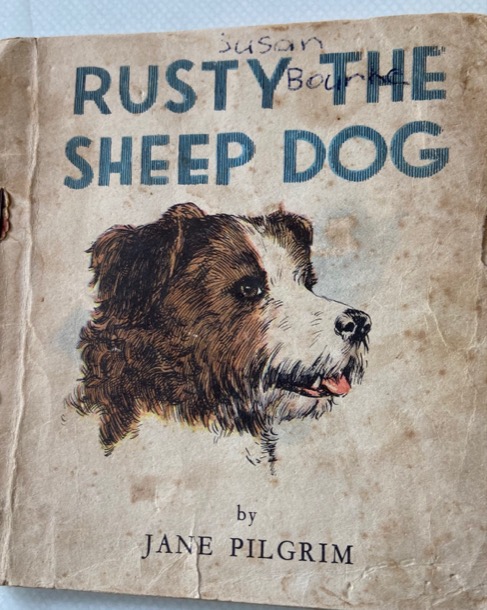

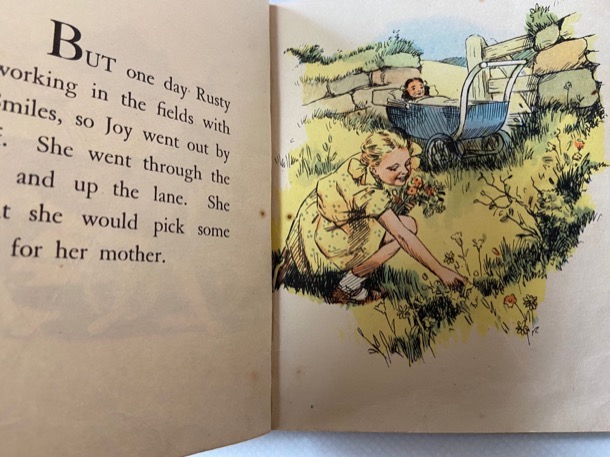

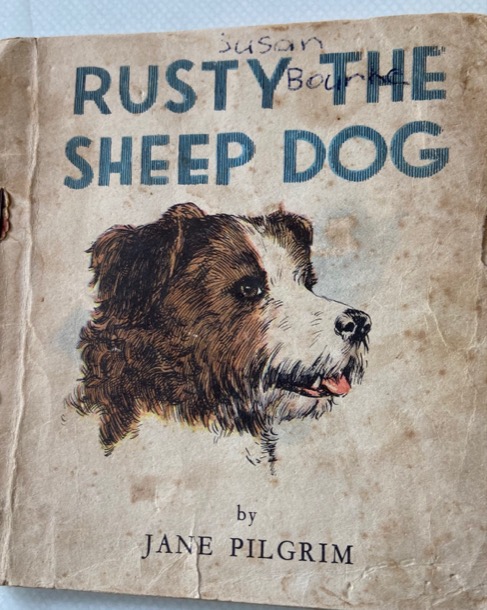

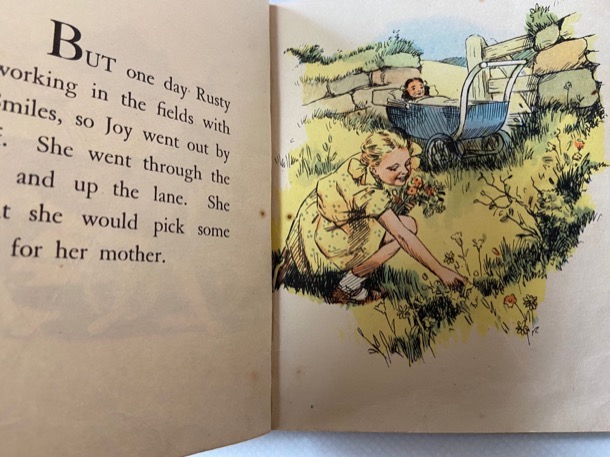

My other strong and pleasant memory is of Rusty the Sheep Dog, which is one of the Blackberry Farm series by English author Jane Pilgrim. Blackberry Farm is situated on the outskirts of an unnamed English village. The farm, a sheep and dairy property, is owned by Mr and Mrs Smiles, who have two children, Joy and Bob. Very proper, very white and very English.

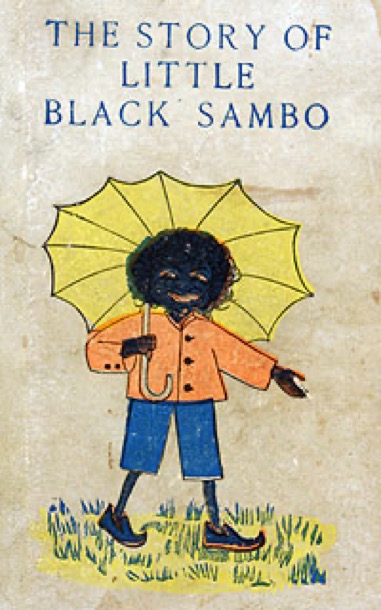

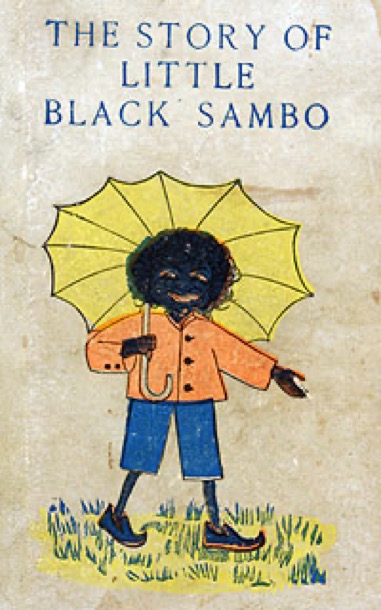

From this we graduated to Noddy and Big Ears complete with culturally inappropriate “golliwogs” and apparently a questionable relationship between Noddy and Big Ears. It all went over our heads, as did the racist overtones in Little Black Sambo. Black Sambo was a little Indian boy whose mother was Black Mumbo and father Black Jumbo.

Oh dear! Once again the stereotyping passed us by. Was it maliciously racist or a product of its times? After all, the author wrote and illustrated the book in 1889., in a Britain which had an imperialist presence in India and an Empire ‘on which the sun never sets’.

Our early schooling took place alongside a fair chunk of the population…. the baby boomers were growing up. It was still “post war” enough in the mid fifties for there to be a shortage of teachers. All this was dealt with by adding more and more desks - class sizes were massive!

The range of abilities in each class was, as always, vast. The single teacher was charged with teaching the more than fifty little souls in front of her how to read. There were no remedial classes, no gifted programs and no differentiated curriculum - sink or swim, and sit down and shut up!

At the time we were in the early grades at school, the “whole word” system was mandated. This has the goal of having “the children recognise the word as having a particular shape or contour, rather than decode the word based on individual letter sounds.”

We remember flash cards - words, phrases and then sentences, which, in sing song little unison voices, we “read”, as the teacher held each card up.

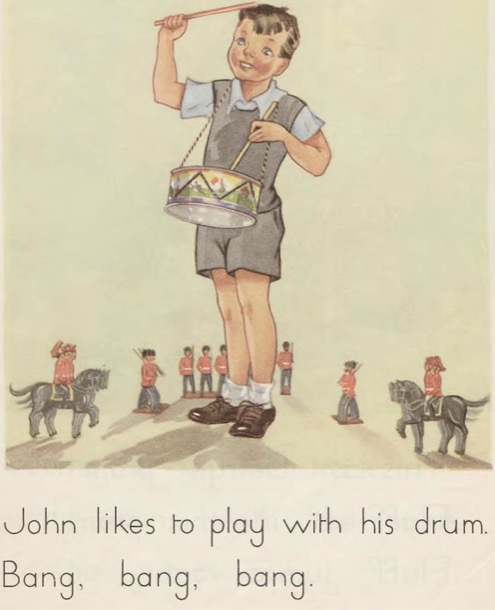

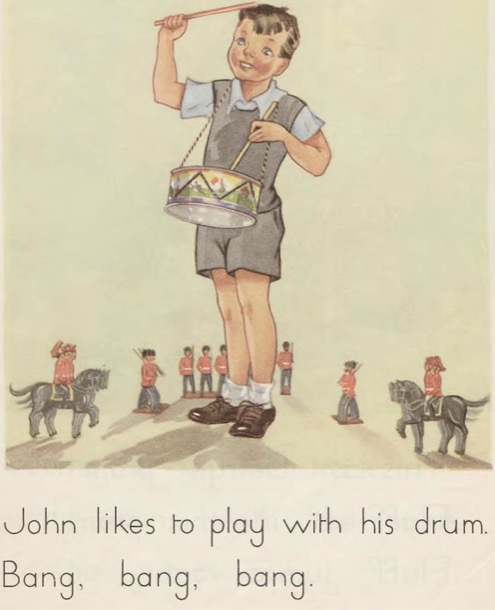

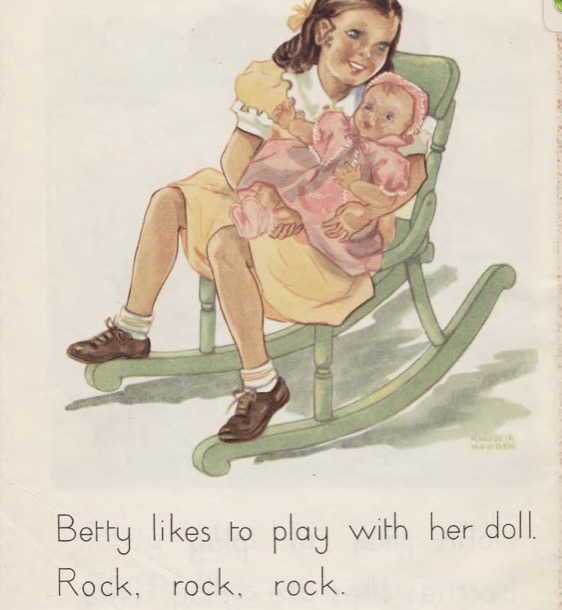

“John”

John likes”

John likes to play.”

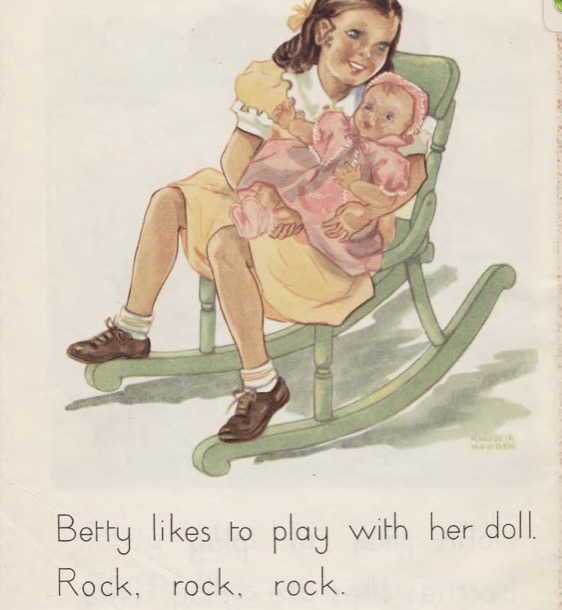

Then, eventually, we read the whole lot. John and Betty was a portrait of little siblings, stereotyped in every possible way one can stereotype!

My main memory of this time is … impatience. I don’t really know when the “being able to read” magic happened. I don’t think I could read before I went to school, but the whole process seemed very slow.

It seems we didn’t have access at school to other books, and I don’t remember reading books at home until a bit later. But I wanted to.

Eventually, enough of the class was deemed to be proficient enough at reading to read other things.

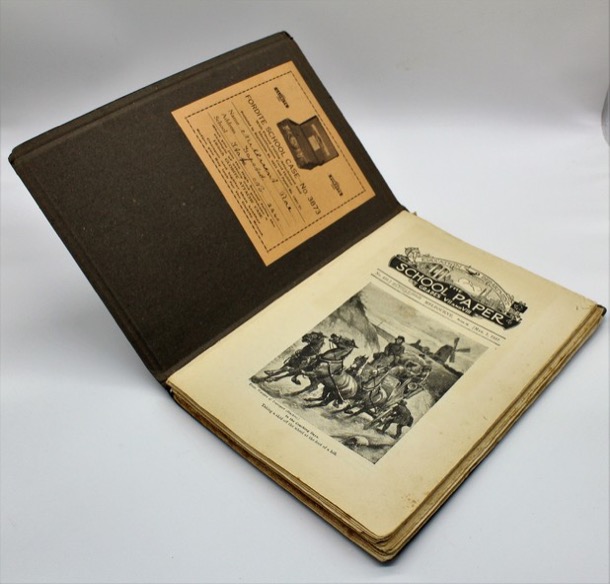

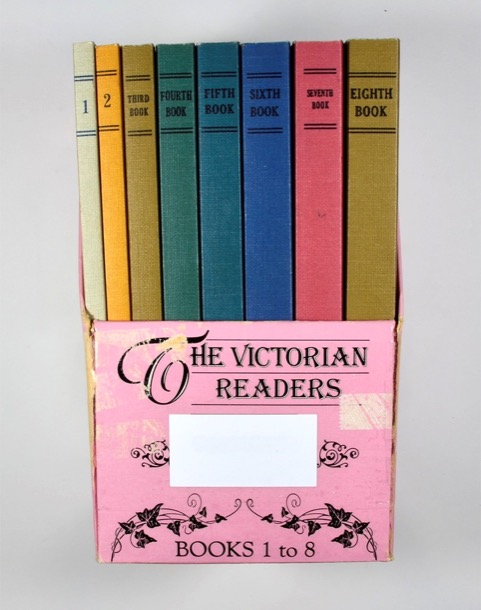

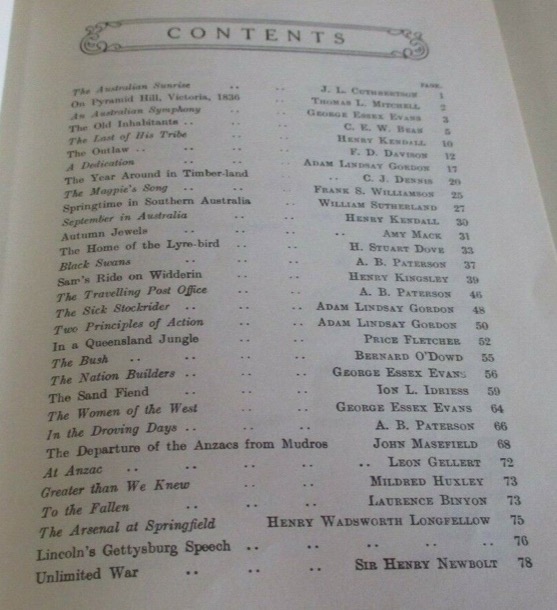

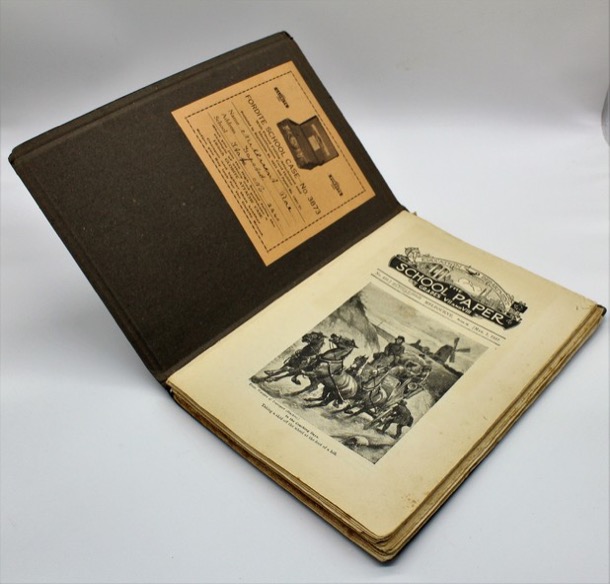

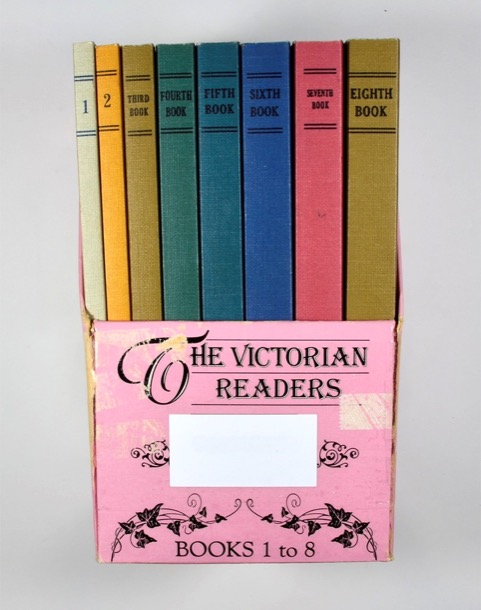

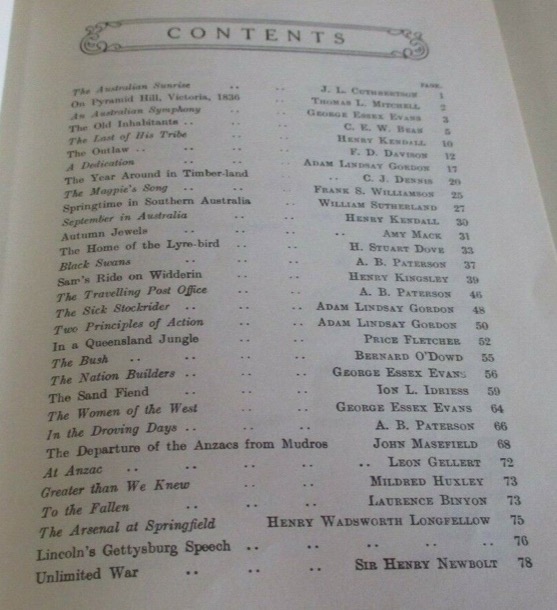

The School Paper, a monthly publication of the Victorian Education Department, was first introduced into Victorian schools in the 1890s.They were compulsory reading in schools until 1928, when the Victorian readers became compulsory and the School papers supplemented them. We remember both, and in our memory, the contents was interchangeable.

The school papers were foolscap sized, printed on fairly cheap paper. At the beginning of the year we all bought a black folder, stiffened cardboard with inner strings ready to contain the twelve issues for the year. Sue says she can remember the smell of the folders.

The readers are collections of stories, poems, illustrations and extracts from longer works, twenty-five percent of which had to be Australian. The rest has a very British flavour. The Australian content focused on white bushmen, pioneers, and settlers with a side serving of heroic Anzacs. The Australian landscape was sentimentalised, even while its “taming” was celebrated.

They are an insight into the values and culture that were being instilled into the population, and also into the standard expected at particular levels.

Clearly, quite a proportion of the class would have found the language incomprehensible, and the content alien.

We can only remember reading the School Paper and Victorian Readers at school. And we kept them in our school desk. Did we own our own copy? Did we have use of them just for the school year?

Once we could read, we had a limited, but much loved selection of books.

Enid Blyton was a staple, once again an English author. We particularly loved the Faraway Tree and Famous Five books. The Faraway Tree was a spreading oak, big enough to have small houses in the trunk. It grew in an enchanted forest and its branches reached up into magical lands, in which many of the adventures took place. Jo, Bessie and Fanny, very English children, share their adventures with the magical residents of the tree, such as Silky and Moonface.

The Famous Five also featured very English children: Julian, Dick, Anne and George [short for Georgina ] and their dog Timmy. Their adventures were much more serious and dangerous, sometimes involving criminals and lost treasure. The vast majority of the stories take place in the children’s school holidays, close to George's family home, Kirrin Cottage. The settings are almost always rural and the children picnic, bike ride and swim in the English and Welsh countryside: very wholesome.

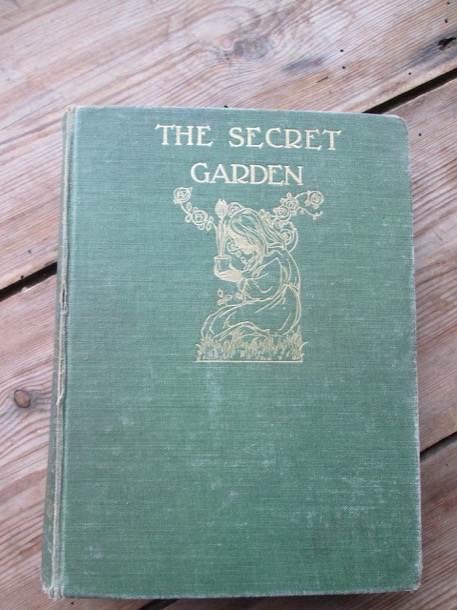

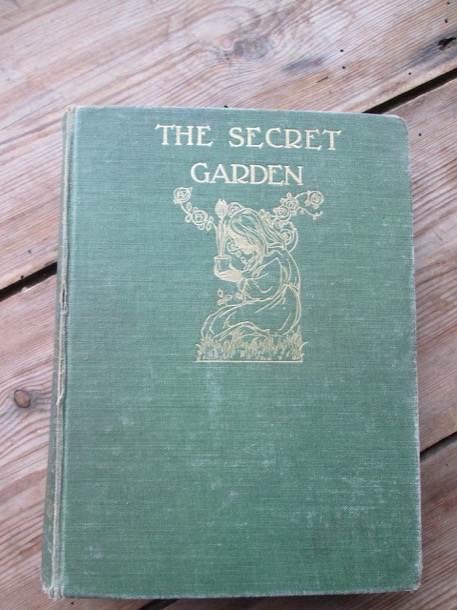

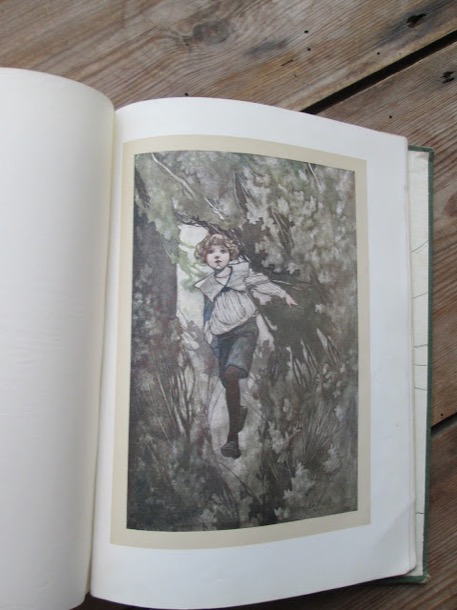

Our grandfather, Mum’s father, also revered books, many with English authors. When we were older we both remember borrowing his books such as George Elliot’s Mill on the Floss.This was a story of Tom and Maggie Tulliver, siblings who grow up at Dorlcote Mill on the River Floss. Another book from ‘the old country’ and a classic of English children’s literature was The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. We read Mum’s copy , a prize from school days. This story is set in a manor house on the Yorkshire moors where Mary Lennox is sent after her parents die in India. She has grown up in colonial India, surrounded by colour and life, and people who always do exactly what she wants, presumably Indian servants. This, like much of our reading matter, reeked of English privilege, class and the trappings of Empire.

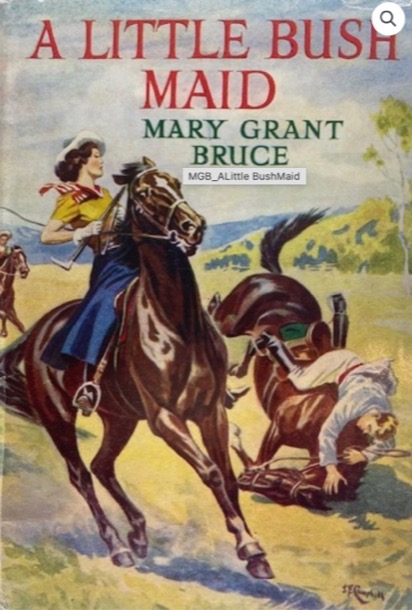

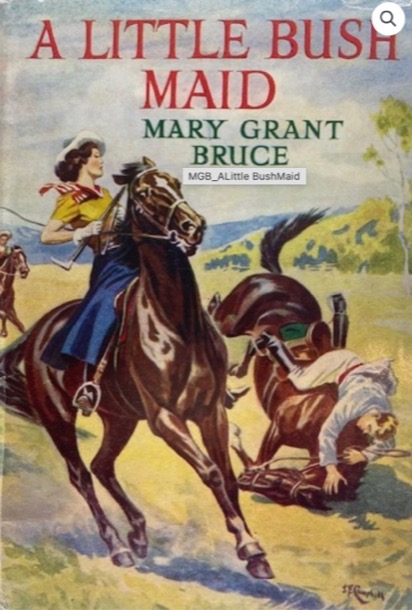

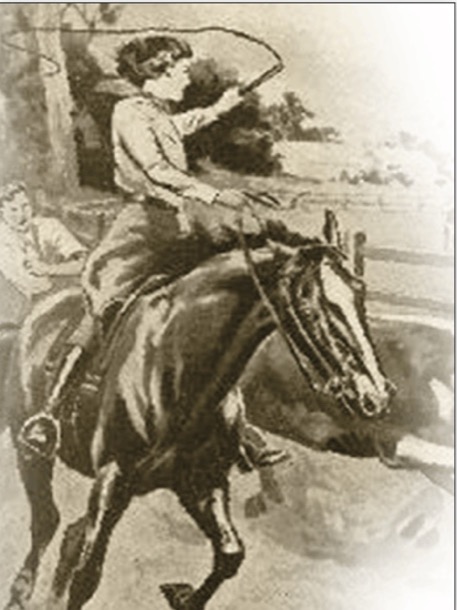

In this environment it is not surprising that Australian literature had similar characteristics. The Billabong books by Mary Grant Bruce, published in 1910, are a prime example. Very Anglo Saxon, gender specific and some would say racist, they represented to our young, innocent minds, adventure, and a glimpse into an idyllic life on a prosperous large property somewhere in Victoria. Twelve year old Norah, the ‘little bush maid’ lives at Billabong Station with her widowed father and brother Jim. Norah rides all over the property on her beloved pony Bobs, joining in the mustering and the “holiday fun” when Jim comes home from boarding school.

This sums up our own reaction to the Billabong books:

‘The Linton family are very much lords of their Australian manor, ruling in a benignly patronising way.The house, large enough to have ‘wings’, is staffed by a doting cook and various ‘girls’. The decorative front garden is maintained by a Scotsman, the vegetable garden and orchard at the rear are looked after by ‘Chinese Lee Wing (and oh isn’t his silly accent funny!) Numerous unnamed men work the farm itself with one of them, called Billy, seemingly assigned to be the children’s personal slave. Billy is never, ever described without with an adjective like “Sable Billy” or “Dusky Billy” or “Black”. And in case the reader hadn’t quite caught on, he is also variously described as careless, lazy or – just once – as a n——r. At 18 years of age Billy is older than the children and, according to Norah’s father, the best hand with a horse he’d ever seen, yet the children casually order him about and call him Boy. Billy, like every 18 year old bossed by a 12 year old girl, living without friends or family, and with no girlfriend in sight, seems perfectly content with his lot.

But, and sadly there always seems to be a but, my beloved Billabong books belong very much to the era in which they were written. Almost every writer I know cites Enid Blyton as one of their favourite childhood authors. She transported them in a way few other writers could. But almost every writer I know is also sorrowfully aware that once you’ve grown up there is no going back to Blyton’s magical worlds. The racism, the class barriers, the gender stereotypes are just too distressingly obvious to make Blyton an enjoyable adult read. And so it is for Billabong.’

Michelle Scott Tucker [Billabong Series, Mary Grant Bruce 2019]

As well as books, there were magazines.

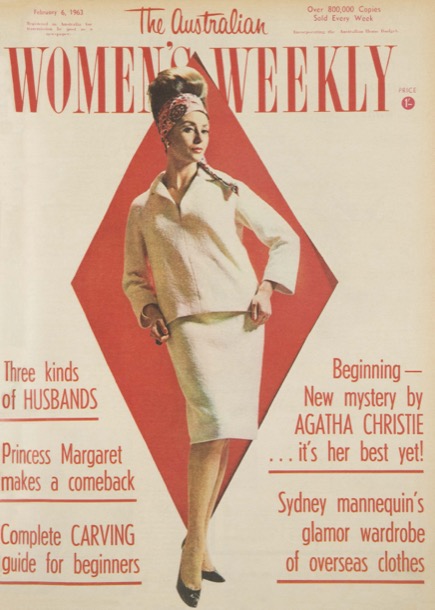

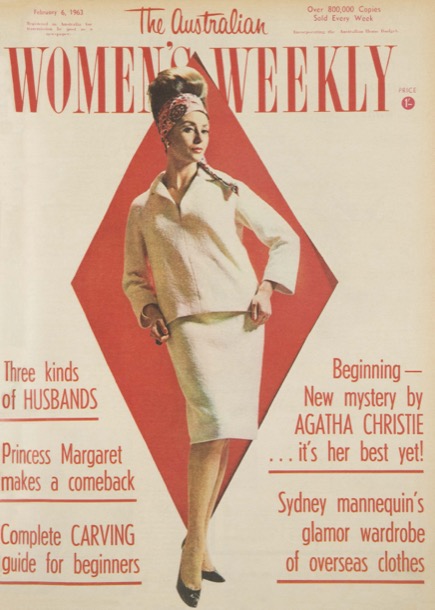

We struggle to remember exactly how frequently we got the Woman’s Weekly magazine. It came out weekly, until 1982, when it became a monthly. We think our mother must have bought occasional ones from the Wattle Park Newsagent. We don’t think we had a subscription, but it is a very clear memory.

It was an important window into Australian suburban culture.

We remember the sections:

Agony aunt, where people would write in asking for relationship advice.

Household hints

Letters

Knitting and sewing patterns

Fashion and make up advice

Recipes

Health items, discussion specifically about women and children

Probably some Hollywood celebrity items, but we don’t remember having much interest in those

Royals. That was much more our cup of tea. After all, our second names are the names of the late queen and her daughter.

… and of course the ads - mostly household items, fashion and make up.

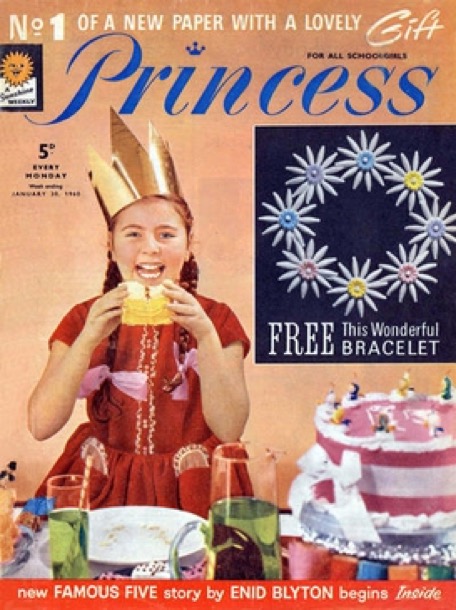

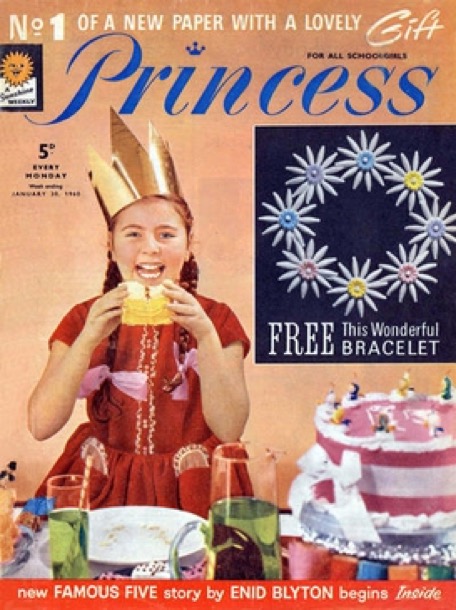

From January 1960, when I was eight and Sue was eleven, we had Princess magazine, a monthly English magazine, aimed at middle class girls. It contained stories, serials, factual articles, all with high quality photos and pictures. Ballet, horses and show jumping, fashion… the content did not have much to do with our own lives, but maybe that’s why we loved it. And there were free gifts!

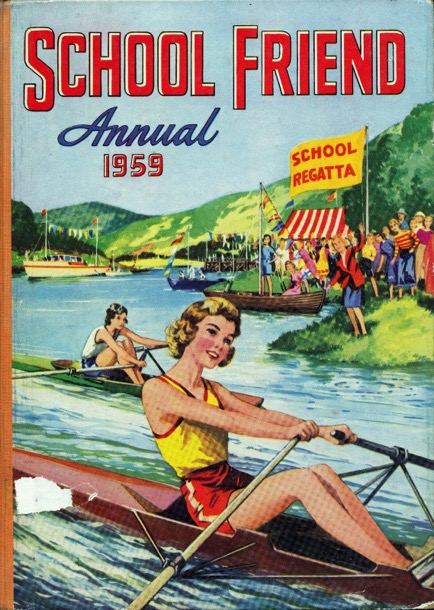

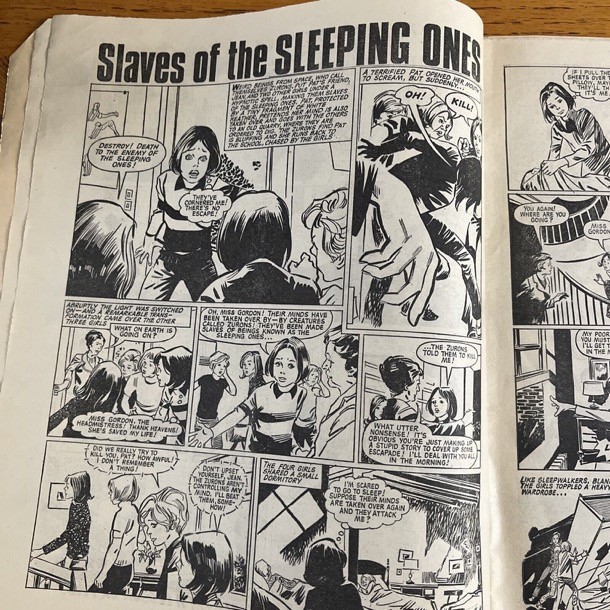

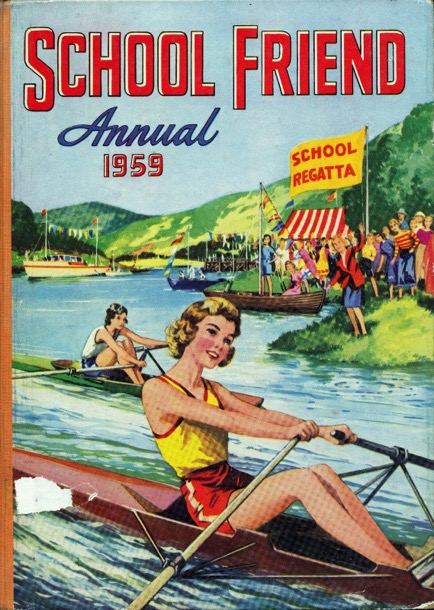

We also loved Schoolfriend magazine and Annuals.

‘Schoolfriend was about the exploits of brave, public school girls at boarding school in England, based on the adventures of pupils in a girls’ boarding school called Cliff House, and featured such characters as Barbara Redfern, Mabel Lyon, Jemima Carstairs – who wore a monocle and had an Eton crop’.

Although the stories featured scenarios in which most children wouldn’t have participated in the 1950s (horse riding, ballet, skiing in the Alps) there was an interesting message being spelled out: in a school environment devoid of males, females were able to assert themselves and reach their full potential.’

from https://johndabell.com/

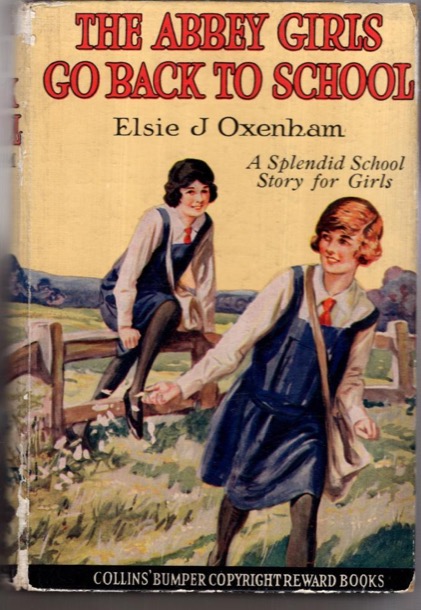

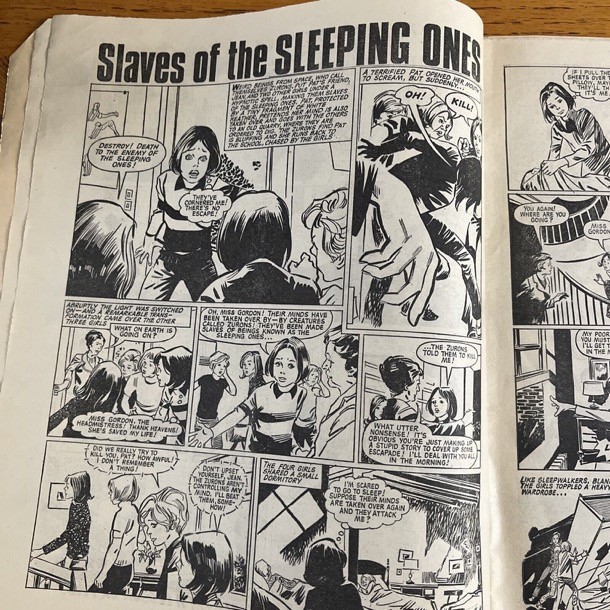

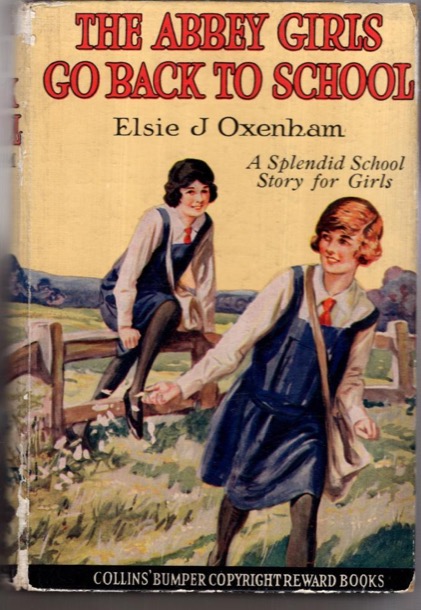

There were English Boarding School books, too.

During our annual six week Christmas holiday camping holidays, reading featured heavily.

My memory is of many nights with the family sitting around in the tent, under the central tilley lamp, wrapped in blankets, reading, in silence. When we look at the timing, it probably only happened for a few years, and it would not have included our little brothers, but it feels like a well established custom.

The books lived in a sturdy wooden box, the “book box”, which, Sue remembers, had dovetailed joints. In my memory, we all dipped into it. Maybe our younger brothers were in bed, or maybe they read other, more suitable books. We don’t remember them being read to.

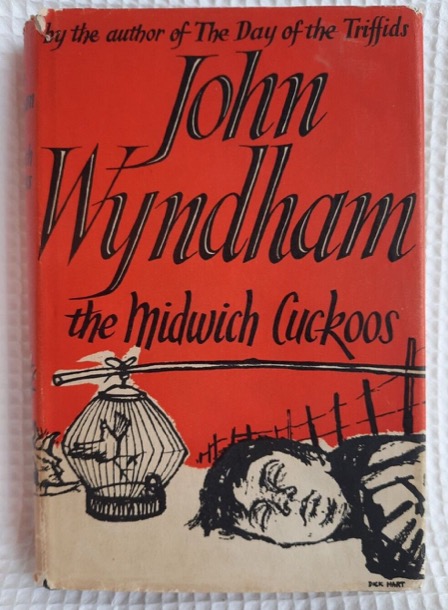

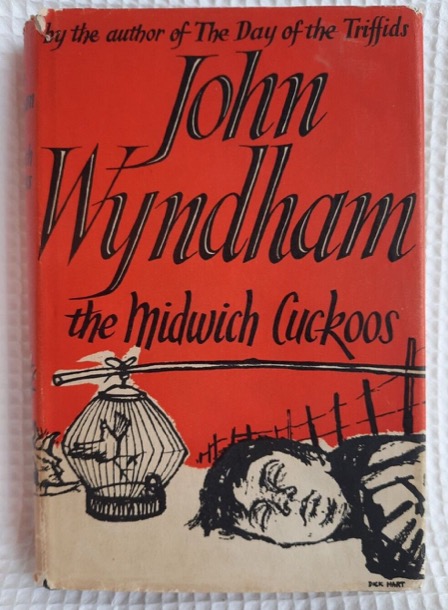

There were a lot of library books, but paper backs featured as well. A brainstorm yields: P D James, Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh and other “who dunnits”, Gerald Durrell’s family stories, AJ Cronin, John Wyndham’s Science fiction, Dr Kildare books.

In general, it’s holiday reading, and pretty light. We remember the books being mostly our father’s choice. There were some we didn’t like, such as Westerns, with pictures on the cover of cowboys on horseback. We don’t remember any censorship, but maybe it was subtle enough for us not to have noticed.

Camping holidays are the only time either of us can remember reading Mum and Dad’s books. We can’t ever remember not having access to books though. As a family we didn’t own many books, we all used the library.

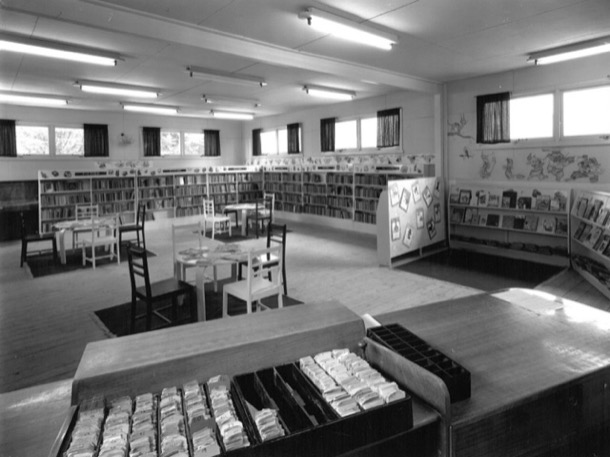

Visits to the Box Hill Junior Library were a regular feature in our childhood. The library was behind the Town Hall and was a very simple weatherboard structure, but inside it seemed there was a never ending supply of books. I never remember not being able to find a book I liked. Library visits must have been fortnightly as that was the borrowing period, so it is no wonder that I can still visualise the interior exactly.

The Billabong books were on the right just past the picture books, top and second shelf down. Once in the door, we would always make a beeline for that shelf to see if the next Billabong book was there. This was particularly important to me as I wanted to read them in order. Margaret does not remember this being a feature of her library visits.

We began this exploration of books in our early life full of the warm memories of specific titles. We already knew that, in our childhood, books were our escape, our entertainment and our cultural education. We buried ourselves in books, and we both remember many hours reading on our beds transported to other worlds.

Over the time we have been talking and writing about this topic, we have realised that the genre that most captured our imagination, and has remained as treasured memories, was actually quite narrow. It was characterised by adventure, characters who were resourceful and brave, often female, and idyllic settings. The action often happened in school holidays, sometimes on islands and beaches or Australian cattle and sheep stations.

We are also struck by the narrowness of the cultural values. We think of our family’s values as progressive, liberal and inclusive. We witnessed no open discrimination in our white suburban neighbourhood. And now, we are surprised at the extent of the sexism, class prejudice and racism in beloved books. It all went completely unnoticed at the time, but our adult, twenty-first century eyes look aghast at the world we immersed ourselves in.

We are three years apart, and our early childhood experiences are quite different. Despite the three year gap, when we read lists of books for little children, from those times, the same titles resonate for both of us.

As we became independent readers, home time meant being left much of the time to our own devices. The municipal library was our source of escapism, adventure and vicarious happiness.

I vividly remember what I assume was a private, lending library coming to the house with blue covered hard back books for Mum and Dad to borrow. I remember the small van parked at the front door and the gentleman, clad in a fawn dust coat, bringing in the books and inserting the borrowing card in the pocket inside the back cover of items borrowed. We cannot find any reference to travelling lending libraries but we surmise that it may have been an offshoot of a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens. Public lending libraries were not established until the 1960s, in response to public pressure. Maybe when Mum and Dad lived with her parents they had all belonged to a private lending library located in Canterbury Gardens, not far from Boronia Street, where they lived.

I loved having Mum read to me.

But Margaret was three years younger and her experience was completely different:

“I was just three when the next baby in line was born. He was premature and challenging, and we think our mother probably found the next few years a very difficult time.

In the years before he was born, she read to Sue, and I was there, but I don’t have much memory of it. I certainly don’t have the strong, warm connection to those books that Sue has. And when I was of an age where they would have been appropriate for me, Mum was caught up with managing the baby, and I was pretty much left to my own devices.

I remember, later on, her reading to our two younger brothers, perhaps when they were about three and five years old. But, by then I was reading for myself.”

One of my earliest memories was of the A.A. Milne books. Milne wrote the story of Winnie-the-Pooh for his son, on whom the character of Christoper Robin was based.

We also had a vinyl record of the poems read by a man, with a very English accent of course. We must have listened to it hundreds of times, as Margaret and I can both recite The King’s Breakfast and some others, with exactly the same rhythm and expression.

My other strong and pleasant memory is of Rusty the Sheep Dog, which is one of the Blackberry Farm series by English author Jane Pilgrim. Blackberry Farm is situated on the outskirts of an unnamed English village. The farm, a sheep and dairy property, is owned by Mr and Mrs Smiles, who have two children, Joy and Bob. Very proper, very white and very English.

From this we graduated to Noddy and Big Ears complete with culturally inappropriate “golliwogs” and apparently a questionable relationship between Noddy and Big Ears. It all went over our heads, as did the racist overtones in Little Black Sambo. Black Sambo was a little Indian boy whose mother was Black Mumbo and father Black Jumbo.

Oh dear! Once again the stereotyping passed us by. Was it maliciously racist or a product of its times? After all, the author wrote and illustrated the book in 1889., in a Britain which had an imperialist presence in India and an Empire ‘on which the sun never sets’.

Our early schooling took place alongside a fair chunk of the population…. the baby boomers were growing up. It was still “post war” enough in the mid fifties for there to be a shortage of teachers. All this was dealt with by adding more and more desks - class sizes were massive!

The range of abilities in each class was, as always, vast. The single teacher was charged with teaching the more than fifty little souls in front of her how to read. There were no remedial classes, no gifted programs and no differentiated curriculum - sink or swim, and sit down and shut up!

At the time we were in the early grades at school, the “whole word” system was mandated. This has the goal of having “the children recognise the word as having a particular shape or contour, rather than decode the word based on individual letter sounds.”

We remember flash cards - words, phrases and then sentences, which, in sing song little unison voices, we “read”, as the teacher held each card up.

“John”

John likes”

John likes to play.”

Then, eventually, we read the whole lot. John and Betty was a portrait of little siblings, stereotyped in every possible way one can stereotype!

My main memory of this time is … impatience. I don’t really know when the “being able to read” magic happened. I don’t think I could read before I went to school, but the whole process seemed very slow.

It seems we didn’t have access at school to other books, and I don’t remember reading books at home until a bit later. But I wanted to.

Eventually, enough of the class was deemed to be proficient enough at reading to read other things.

The School Paper, a monthly publication of the Victorian Education Department, was first introduced into Victorian schools in the 1890s.They were compulsory reading in schools until 1928, when the Victorian readers became compulsory and the School papers supplemented them. We remember both, and in our memory, the contents was interchangeable.

The school papers were foolscap sized, printed on fairly cheap paper. At the beginning of the year we all bought a black folder, stiffened cardboard with inner strings ready to contain the twelve issues for the year. Sue says she can remember the smell of the folders.

The readers are collections of stories, poems, illustrations and extracts from longer works, twenty-five percent of which had to be Australian. The rest has a very British flavour. The Australian content focused on white bushmen, pioneers, and settlers with a side serving of heroic Anzacs. The Australian landscape was sentimentalised, even while its “taming” was celebrated.

They are an insight into the values and culture that were being instilled into the population, and also into the standard expected at particular levels.

Clearly, quite a proportion of the class would have found the language incomprehensible, and the content alien.

We can only remember reading the School Paper and Victorian Readers at school. And we kept them in our school desk. Did we own our own copy? Did we have use of them just for the school year?

Once we could read, we had a limited, but much loved selection of books.

Enid Blyton was a staple, once again an English author. We particularly loved the Faraway Tree and Famous Five books. The Faraway Tree was a spreading oak, big enough to have small houses in the trunk. It grew in an enchanted forest and its branches reached up into magical lands, in which many of the adventures took place. Jo, Bessie and Fanny, very English children, share their adventures with the magical residents of the tree, such as Silky and Moonface.

The Famous Five also featured very English children: Julian, Dick, Anne and George [short for Georgina ] and their dog Timmy. Their adventures were much more serious and dangerous, sometimes involving criminals and lost treasure. The vast majority of the stories take place in the children’s school holidays, close to George's family home, Kirrin Cottage. The settings are almost always rural and the children picnic, bike ride and swim in the English and Welsh countryside: very wholesome.

Our grandfather, Mum’s father, also revered books, many with English authors. When we were older we both remember borrowing his books such as George Elliot’s Mill on the Floss.This was a story of Tom and Maggie Tulliver, siblings who grow up at Dorlcote Mill on the River Floss. Another book from ‘the old country’ and a classic of English children’s literature was The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. We read Mum’s copy , a prize from school days. This story is set in a manor house on the Yorkshire moors where Mary Lennox is sent after her parents die in India. She has grown up in colonial India, surrounded by colour and life, and people who always do exactly what she wants, presumably Indian servants. This, like much of our reading matter, reeked of English privilege, class and the trappings of Empire.

In this environment it is not surprising that Australian literature had similar characteristics. The Billabong books by Mary Grant Bruce, published in 1910, are a prime example. Very Anglo Saxon, gender specific and some would say racist, they represented to our young, innocent minds, adventure, and a glimpse into an idyllic life on a prosperous large property somewhere in Victoria. Twelve year old Norah, the ‘little bush maid’ lives at Billabong Station with her widowed father and brother Jim. Norah rides all over the property on her beloved pony Bobs, joining in the mustering and the “holiday fun” when Jim comes home from boarding school.

This sums up our own reaction to the Billabong books:

‘The Linton family are very much lords of their Australian manor, ruling in a benignly patronising way.The house, large enough to have ‘wings’, is staffed by a doting cook and various ‘girls’. The decorative front garden is maintained by a Scotsman, the vegetable garden and orchard at the rear are looked after by ‘Chinese Lee Wing (and oh isn’t his silly accent funny!) Numerous unnamed men work the farm itself with one of them, called Billy, seemingly assigned to be the children’s personal slave. Billy is never, ever described without with an adjective like “Sable Billy” or “Dusky Billy” or “Black”. And in case the reader hadn’t quite caught on, he is also variously described as careless, lazy or – just once – as a n——r. At 18 years of age Billy is older than the children and, according to Norah’s father, the best hand with a horse he’d ever seen, yet the children casually order him about and call him Boy. Billy, like every 18 year old bossed by a 12 year old girl, living without friends or family, and with no girlfriend in sight, seems perfectly content with his lot.

But, and sadly there always seems to be a but, my beloved Billabong books belong very much to the era in which they were written. Almost every writer I know cites Enid Blyton as one of their favourite childhood authors. She transported them in a way few other writers could. But almost every writer I know is also sorrowfully aware that once you’ve grown up there is no going back to Blyton’s magical worlds. The racism, the class barriers, the gender stereotypes are just too distressingly obvious to make Blyton an enjoyable adult read. And so it is for Billabong.’

Michelle Scott Tucker [Billabong Series, Mary Grant Bruce 2019]

As well as books, there were magazines.

We struggle to remember exactly how frequently we got the Woman’s Weekly magazine. It came out weekly, until 1982, when it became a monthly. We think our mother must have bought occasional ones from the Wattle Park Newsagent. We don’t think we had a subscription, but it is a very clear memory.

It was an important window into Australian suburban culture.

We remember the sections:

Agony aunt, where people would write in asking for relationship advice.

Household hints

Letters

Knitting and sewing patterns

Fashion and make up advice

Recipes

Health items, discussion specifically about women and children

Probably some Hollywood celebrity items, but we don’t remember having much interest in those

Royals. That was much more our cup of tea. After all, our second names are the names of the late queen and her daughter.

… and of course the ads - mostly household items, fashion and make up.

From January 1960, when I was eight and Sue was eleven, we had Princess magazine, a monthly English magazine, aimed at middle class girls. It contained stories, serials, factual articles, all with high quality photos and pictures. Ballet, horses and show jumping, fashion… the content did not have much to do with our own lives, but maybe that’s why we loved it. And there were free gifts!

We also loved Schoolfriend magazine and Annuals.

‘Schoolfriend was about the exploits of brave, public school girls at boarding school in England, based on the adventures of pupils in a girls’ boarding school called Cliff House, and featured such characters as Barbara Redfern, Mabel Lyon, Jemima Carstairs – who wore a monocle and had an Eton crop’.

Although the stories featured scenarios in which most children wouldn’t have participated in the 1950s (horse riding, ballet, skiing in the Alps) there was an interesting message being spelled out: in a school environment devoid of males, females were able to assert themselves and reach their full potential.’

from https://johndabell.com/

There were English Boarding School books, too.

During our annual six week Christmas holiday camping holidays, reading featured heavily.

My memory is of many nights with the family sitting around in the tent, under the central tilley lamp, wrapped in blankets, reading, in silence. When we look at the timing, it probably only happened for a few years, and it would not have included our little brothers, but it feels like a well established custom.

The books lived in a sturdy wooden box, the “book box”, which, Sue remembers, had dovetailed joints. In my memory, we all dipped into it. Maybe our younger brothers were in bed, or maybe they read other, more suitable books. We don’t remember them being read to.

There were a lot of library books, but paper backs featured as well. A brainstorm yields: P D James, Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh and other “who dunnits”, Gerald Durrell’s family stories, AJ Cronin, John Wyndham’s Science fiction, Dr Kildare books.

In general, it’s holiday reading, and pretty light. We remember the books being mostly our father’s choice. There were some we didn’t like, such as Westerns, with pictures on the cover of cowboys on horseback. We don’t remember any censorship, but maybe it was subtle enough for us not to have noticed.

Camping holidays are the only time either of us can remember reading Mum and Dad’s books. We can’t ever remember not having access to books though. As a family we didn’t own many books, we all used the library.

Visits to the Box Hill Junior Library were a regular feature in our childhood. The library was behind the Town Hall and was a very simple weatherboard structure, but inside it seemed there was a never ending supply of books. I never remember not being able to find a book I liked. Library visits must have been fortnightly as that was the borrowing period, so it is no wonder that I can still visualise the interior exactly.

The Billabong books were on the right just past the picture books, top and second shelf down. Once in the door, we would always make a beeline for that shelf to see if the next Billabong book was there. This was particularly important to me as I wanted to read them in order. Margaret does not remember this being a feature of her library visits.

We began this exploration of books in our early life full of the warm memories of specific titles. We already knew that, in our childhood, books were our escape, our entertainment and our cultural education. We buried ourselves in books, and we both remember many hours reading on our beds transported to other worlds.

Over the time we have been talking and writing about this topic, we have realised that the genre that most captured our imagination, and has remained as treasured memories, was actually quite narrow. It was characterised by adventure, characters who were resourceful and brave, often female, and idyllic settings. The action often happened in school holidays, sometimes on islands and beaches or Australian cattle and sheep stations.

We are also struck by the narrowness of the cultural values. We think of our family’s values as progressive, liberal and inclusive. We witnessed no open discrimination in our white suburban neighbourhood. And now, we are surprised at the extent of the sexism, class prejudice and racism in beloved books. It all went completely unnoticed at the time, but our adult, twenty-first century eyes look aghast at the world we immersed ourselves in.

blog comments powered by Disqus