Maribyrnong

Hair

08 02 23 13:08 Filed in: Alice

Our plan was to write about hairstyles. Many of our family photos feature the hairstyles that were popular at the time, so we spent a long time gazing at the photos. Soon we found ourselves discussing particular people: their lives, their relationships, the circumstances of particular photos.

This post therefore is about hairstyles, but we have allowed ourselves a much broader scope.

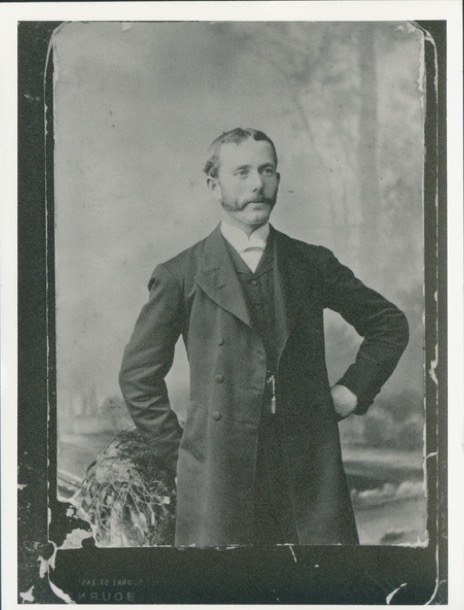

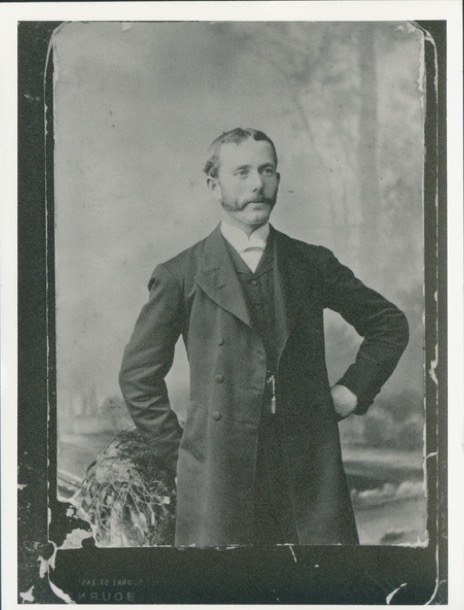

ALFRED JOHN COATES

Alfred John Coates, born in 1857, was probably in his late twenties when this photo was taken. He was our maternal great grandfather and was a Methodist Pastor for most of his working life. In this photograph Alfred is a young man in prime of life, dressed in formal dress and sporting the fashion of the day: mutton chop whiskers, carefully manicured to join artfully with the moustache. A man of destiny, the misty ‘bush’ behind him, he stands erect, eyes on the future. At this time Alfred was apparently a boiler maker in Ballarat.

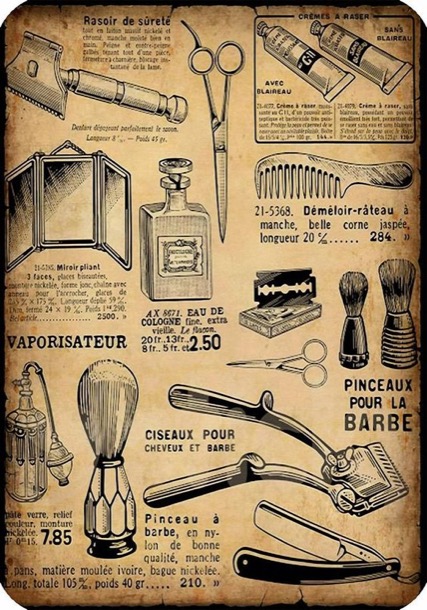

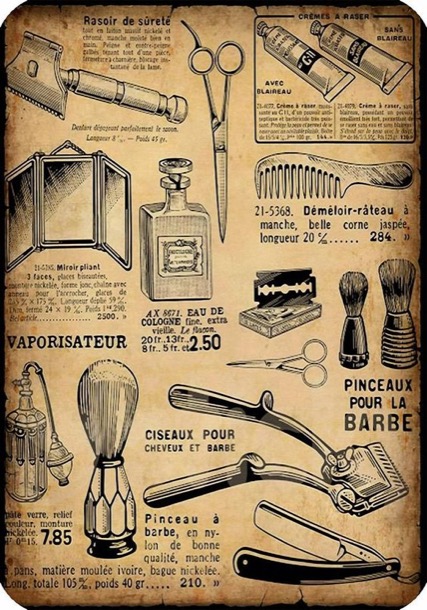

Men’s facial hair trends were changing rapidly in the late 1800s. Long beards were out and clean chins and cheeks and a well-manicured moustache were in. To achieve this look men would need to go to a barber two to three times a week or shave themselves.

Shaving oneself may have been a financial necessity at times but it could also be a dangerous procedure. Shaving was done with a straight steel razor that required care and expertise, not only in the act of shaving the gentleman, but also in the care of the blade. To keep it sharp, the blade was rubbed against a leather or canvas strap before each new shave. As well as the blade, shaving soap, shaving brushes, combs, oils and wax were essential items to achieve the desired effect.

Having a photograph taken in a studio was a special occasion and a relatively expensive exercise. One can imagine that Alfred may have had a trip to the barber to ensure that he looked his best.

Safety steel razor blades that made shaving much easier were not invented until 1895 by an American business man with French heritage.

King C. Gillette invented a low cost blade that was easily replaceable and gave men safety and the freedom to achieve the look desired themselves.

EMMA ELIZABETH DAU

Alfred married Emma Elizabeth Dau in 1888. He was thirty-two and she was twenty Maybe this photo was taken at this time:

Emma is dressed in the style of the day, hourglass figure no doubt with a corseted waist as she gazes into her future with a determined tilt of her chin. Her hair is tightly curled at the front and pulled back into either a bun or pinned up plait.

Unlike the men who had barbers to attend to their needs, there don’t appear to be many ladies' hairdressers. Women had many home implements and potions and maybe sisters and mothers helped each other with their hair.

Young Emma’s tight curls may have been created with curling irons. A curling iron consisted of a metal rod that was held over a flame or burning alcohol to heat it, before wrapping the hair around it. Hey presto, curls!

Later in life, Emma wore her hair in a more relaxed style, loosely pulled back from her face and pinned up into a bun at the back:

When this photo was taken, the height of fashion for women was to wear their hair with more volume at the sides. This was created by using clumps of hair leftover in combs and brushes, to pad out the sides. Emma would not have gone to these lengths in later life, but on her dressing table she would have had a brush, comb, hand mirror and china box, with a lid for the collection of hair caught in brushes or combs. We can remember our grandmother, Alfreda, also having these items on her dressing table. She wore her hair long all her life. During the day it was loosely tied back in a bun, brushed out at night, and the ‘ratts’ collected from the brush and placed in the china box. She then plaited her hair into a loose, single long plait and was ready for bed.

NINE DAU SISTERS

Emma Coates, was born Emma Dau. She was one of seventeen. The first nine of these were girls.

We have three amazing little photos of some of the Dau children. We have spent a long time staring at these images, noticing little details, wondering about the lives of these nine little girls.

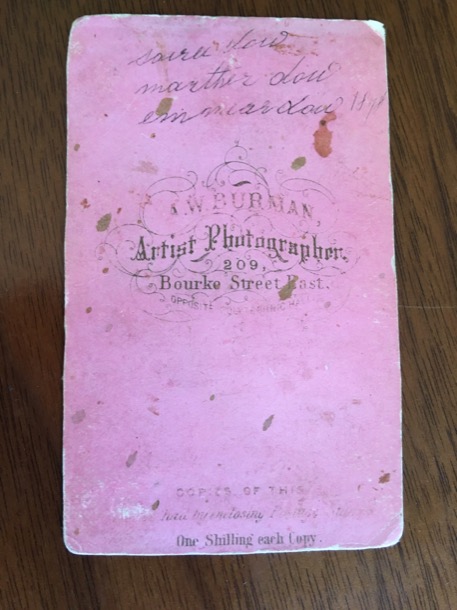

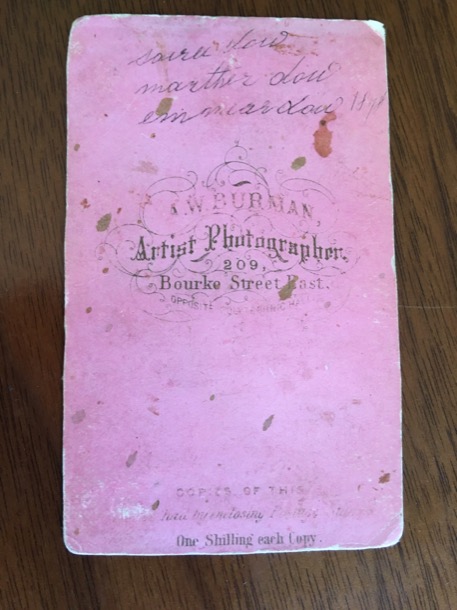

The first question we had was, "Were the three photos taken at the same time?". There is such a family resemblance, we weren’t sure at first whether they were different people in the three photos. The carpet gives away that they were taken in the same studio. On the back of one of the playing card sized photos, we see “one shilling per copy”. For context, at that time, a shilling was more than a day’s wage for a working man.

It seems most likely that the three photos were taken on the same day, and they are the nine oldest children, all daughters, of Joachim and Martha Dau, our great, great grandparents.

The photo of the three eldest has writing on the back:

The fact that Martha is misspelt as “marther”, and that no capital letters are used, might be a clue. It was not our mother Alice, nor her parents. None of them would have made such a basic spelling error! The surname is listed as “Dow”.

If those names are correct, then these are the three eldest Dau children. Standing is Sarah, the eldest. the other two are Martha, known as Mishi, and Emma, our great grandmother.

Thanks to the Wandong Historical group, we have the details of nearly all the Dau children.

The next three girls are Bella, Jane and Sophia, followed by Alice, and two others, possibly Annie and Nance, although some sources have Annie and Nance as the same person.

There is no date on these photos, but there are nine girls. The nine first Dau children, all girls were born between 1866 and about 1878. This puts the date of the photos at about 1880, with Sarah, the eldest, aged 14 and the youngest aged 2.

The girls’ father, Joachim, had spelt his surname, Dau. We don’t know the exact date they changed it to Dow, but Frederick enlisted to fight in the Boer War as Dow in 1901, and Arthur, who became a professional soldier, changed his name by deed poll to Dow. The same anti German sentiment that caused the British Royals to change their surname to Windsor from Saax Coburg was no doubt responsible. And yet the Dau spelling persists alongside the Dow spelling, right up until 1929, when Sarah, the eldest wrote about her childhood. Our mother and aunt did not even know about the Dau spelling.

The photographer is listed on the back as Burman, 209 Bourke St Melbourne. The building is still there. This is what it looks like today:

There are a number of old photos by Burman available on line, with that tell-tale carpet visible in some. This one, “Portrait of a Lady”, which uses the same chair as two of our photos, is from C1865.

We picture the little farm girls, in their new dresses, in the big noisy city. They would have come on the train, to Flinders Street from Wallan, and walked the three city blocks to the studio.

The city streets would have looked like this:

Their hair would had been in rags overnight. The curls in Sarah, Martha and Emma’s hair have been successful; the others less so. All of them have a ribbon holding their hair back from their face.

The dresses are interesting. The same fabric and pattern seems to have been used for the three eldest girls. Who made them? The next three also have a similar style. All have sturdy boots and frilly pantaloons. These outfits would have been worn to church on Sundays. Did they wear them for the train journey, or change at the studio?

The only other girl, born in 1887, preceded and followed by the seven boys, was Ethel. She wrote diary entries, still held by the Wandong Historical group. Ethel wrote about the boots, which are such a feature of these little girls’ photos. “the rough track across the paddocks and hills, two miles to the little school at Wandong. In wintertime, we had to cross many flooded gullies. We wore strong boots and I was often peeved, as I compared my strong shoes with the dainty ones worn by the other girls at school.”

It was quite an expense to provide boots for so many children.

Our appetite for finding out more about this family is well and truly whetted. We plan further exploration, including an excursion to Wandong.

THREE HOLM SISTERS

These three young women, probably photographed just before the first world war are (left to right) Alfreda, Beatrice and Berta Holm. Alfreda, our maternal grandmother, was the oldest of the three, perhaps just twenty at the time. The three sisters have their long hair swept back in gentle waves, to a loose bun or twist at the back.

We wonder whether they did the white work on their shirts? We know that Beatrice and Berta spent time working in Finders Lane, doing the white embroidery known at the time as “white work”. So much we can only guess at.

They all gaze into the distance: Alfreda with a determined steely gaze, Beat with a quizzical half smile and Bert’s beautiful eyes not quite hiding her vulnerability. We can only guess, as they gaze into a future where world war is imminent.

Alfreda wore her hair long all her life. We can remember her brushing her hair at night and putting it into a long plait.

TWO COATES SISTERS

It’s hard to be a younger sister, but our mother Alice, was the fairly plain younger sister of an extraordinary beauty.

She didn’t have to deal with social media, but, when she was growing up in the 1930s, feminine beauty was important for girls.

Alice was an intelligent and able scholar, and, thank goodness, this was highly valued in her family. Her mother, Alfreda, had made sacrifices and fought for her own education. For their later secondary school, the girls were sent, at huge expense, to a city based secondary school, all the way from Croydon.

Only the wealthiest or most determined families sent their girls to school, after the age of fourteen. At McRobinson Girls’ High School, Marge and Alice were taught by, and shared classes with, the very brightest and best: future women scientists, lawyers and doctors, who would pave the way for our own generation.

But, from her school reports, we see that, while she held her own on the whole, Alice was not exceptional in that auspicious company. And she was crippled, probably her whole life, by a sense of inferiority.

And it is in their respective hair cuts from that time, that we see how the contrast between the two girls was accentuated.

When I stare at those grainy old photos, at Marge’s lush locks, and Alice’s blunt, unfashionable short bob, and straight fringe, I cannot help but ask “Why?”. Why did Alfreda allow her younger daughter to wear such an unflattering style. Why was the difference in feminine beauty accentuated and underlined so prominently by the two hairstyles? How might Alice’s life have been different, had she been encouraged to make the most of her looks, as well as her brains?

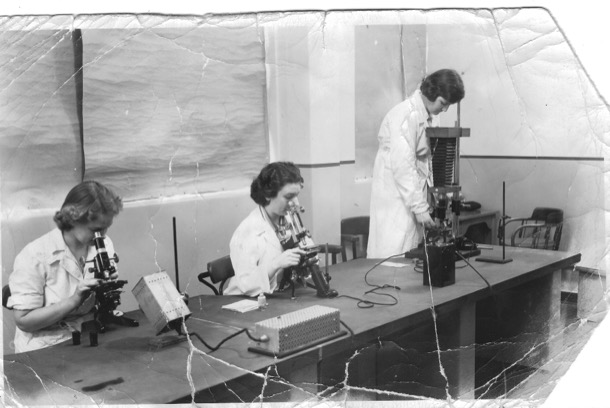

Even as they began working life, both at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory, in 1939, the difference remained. Here Marge is on the far right, and Alice on the far left. Alice is nineteen and Marge twenty-one. But the choice of hairstyle reflects very different attitudes about their appearance:

THE VICTORY ROLL

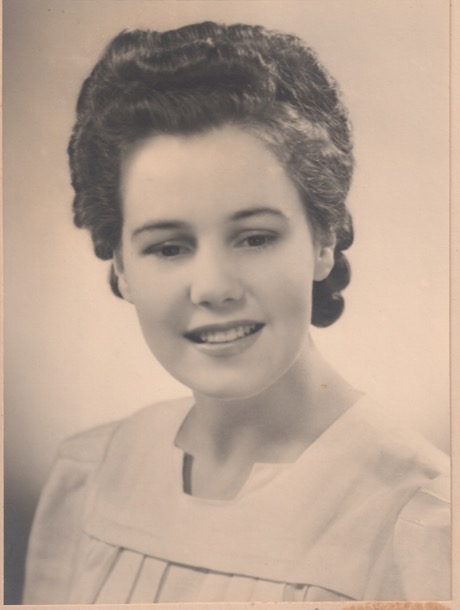

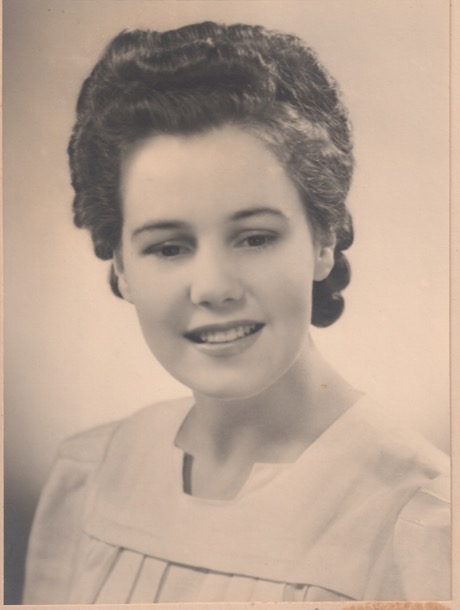

These two studio photographs of Marge are portraits of a beautiful young woman, but what does the hair tell us?

Here, a younger Marge still has very long hair, worn up now, as befitted a young woman who was no longer a child. Pretty curls and barrel curls were the look, and Marge had beautiful, wavy, very cooperative hair and was able to construct ‘the look’ very successfully.

An older Marge, maybe just twenty, posed for this studio photograph as a young woman of the war years, in the “hottest” style of the time. This photograph shows a confident young woman with a job, and presumably many admirers.

During the war, particularly during the Battle of Britain, the ‘Victory Roll’ evolved as a very popular and flattering hairstyle. The style was based on an aerobatic manoeuvre performed by pilots to signify victory. The planes would spin horizontally in celebration. The ‘Victory Roll’ hairstyle would have been difficult to execute, so hours of practice and experimentation was required. The style has stood the test of time, as it is still popular today in ‘retro’ dressing. There are many YouTube videos available with full and detailed instructions.

‘THE SET ‘

After the second world war, women’s hair fashion was dominated by ‘the set’, often a weekly set. Some women did their own at home, but others, such as our mother Alice, went to their local hairdresser.

The set involved a headful of rollers, tightly wound on wet hair, then dried under a hood dryer. This often took almost an hour, so there was time to read or chat.

Through the ages, and the generations of our family, both sexes’ hair styles have been influenced by the fashion of the day. We have all had cuts, or not. We have curled and permed and coloured and bleached, with varied results.

Today, people are not rigidly restricted to one style, as they were in the past, but have any options.

The lyrics from the musical Hair says it all: .

This post therefore is about hairstyles, but we have allowed ourselves a much broader scope.

ALFRED JOHN COATES

Alfred John Coates, born in 1857, was probably in his late twenties when this photo was taken. He was our maternal great grandfather and was a Methodist Pastor for most of his working life. In this photograph Alfred is a young man in prime of life, dressed in formal dress and sporting the fashion of the day: mutton chop whiskers, carefully manicured to join artfully with the moustache. A man of destiny, the misty ‘bush’ behind him, he stands erect, eyes on the future. At this time Alfred was apparently a boiler maker in Ballarat.

Men’s facial hair trends were changing rapidly in the late 1800s. Long beards were out and clean chins and cheeks and a well-manicured moustache were in. To achieve this look men would need to go to a barber two to three times a week or shave themselves.

Shaving oneself may have been a financial necessity at times but it could also be a dangerous procedure. Shaving was done with a straight steel razor that required care and expertise, not only in the act of shaving the gentleman, but also in the care of the blade. To keep it sharp, the blade was rubbed against a leather or canvas strap before each new shave. As well as the blade, shaving soap, shaving brushes, combs, oils and wax were essential items to achieve the desired effect.

Having a photograph taken in a studio was a special occasion and a relatively expensive exercise. One can imagine that Alfred may have had a trip to the barber to ensure that he looked his best.

Safety steel razor blades that made shaving much easier were not invented until 1895 by an American business man with French heritage.

King C. Gillette invented a low cost blade that was easily replaceable and gave men safety and the freedom to achieve the look desired themselves.

EMMA ELIZABETH DAU

Alfred married Emma Elizabeth Dau in 1888. He was thirty-two and she was twenty Maybe this photo was taken at this time:

Emma is dressed in the style of the day, hourglass figure no doubt with a corseted waist as she gazes into her future with a determined tilt of her chin. Her hair is tightly curled at the front and pulled back into either a bun or pinned up plait.

Unlike the men who had barbers to attend to their needs, there don’t appear to be many ladies' hairdressers. Women had many home implements and potions and maybe sisters and mothers helped each other with their hair.

Young Emma’s tight curls may have been created with curling irons. A curling iron consisted of a metal rod that was held over a flame or burning alcohol to heat it, before wrapping the hair around it. Hey presto, curls!

Later in life, Emma wore her hair in a more relaxed style, loosely pulled back from her face and pinned up into a bun at the back:

When this photo was taken, the height of fashion for women was to wear their hair with more volume at the sides. This was created by using clumps of hair leftover in combs and brushes, to pad out the sides. Emma would not have gone to these lengths in later life, but on her dressing table she would have had a brush, comb, hand mirror and china box, with a lid for the collection of hair caught in brushes or combs. We can remember our grandmother, Alfreda, also having these items on her dressing table. She wore her hair long all her life. During the day it was loosely tied back in a bun, brushed out at night, and the ‘ratts’ collected from the brush and placed in the china box. She then plaited her hair into a loose, single long plait and was ready for bed.

NINE DAU SISTERS

Emma Coates, was born Emma Dau. She was one of seventeen. The first nine of these were girls.

We have three amazing little photos of some of the Dau children. We have spent a long time staring at these images, noticing little details, wondering about the lives of these nine little girls.

The first question we had was, "Were the three photos taken at the same time?". There is such a family resemblance, we weren’t sure at first whether they were different people in the three photos. The carpet gives away that they were taken in the same studio. On the back of one of the playing card sized photos, we see “one shilling per copy”. For context, at that time, a shilling was more than a day’s wage for a working man.

It seems most likely that the three photos were taken on the same day, and they are the nine oldest children, all daughters, of Joachim and Martha Dau, our great, great grandparents.

The photo of the three eldest has writing on the back:

The fact that Martha is misspelt as “marther”, and that no capital letters are used, might be a clue. It was not our mother Alice, nor her parents. None of them would have made such a basic spelling error! The surname is listed as “Dow”.

If those names are correct, then these are the three eldest Dau children. Standing is Sarah, the eldest. the other two are Martha, known as Mishi, and Emma, our great grandmother.

Thanks to the Wandong Historical group, we have the details of nearly all the Dau children.

The next three girls are Bella, Jane and Sophia, followed by Alice, and two others, possibly Annie and Nance, although some sources have Annie and Nance as the same person.

There is no date on these photos, but there are nine girls. The nine first Dau children, all girls were born between 1866 and about 1878. This puts the date of the photos at about 1880, with Sarah, the eldest, aged 14 and the youngest aged 2.

The girls’ father, Joachim, had spelt his surname, Dau. We don’t know the exact date they changed it to Dow, but Frederick enlisted to fight in the Boer War as Dow in 1901, and Arthur, who became a professional soldier, changed his name by deed poll to Dow. The same anti German sentiment that caused the British Royals to change their surname to Windsor from Saax Coburg was no doubt responsible. And yet the Dau spelling persists alongside the Dow spelling, right up until 1929, when Sarah, the eldest wrote about her childhood. Our mother and aunt did not even know about the Dau spelling.

The photographer is listed on the back as Burman, 209 Bourke St Melbourne. The building is still there. This is what it looks like today:

There are a number of old photos by Burman available on line, with that tell-tale carpet visible in some. This one, “Portrait of a Lady”, which uses the same chair as two of our photos, is from C1865.

We picture the little farm girls, in their new dresses, in the big noisy city. They would have come on the train, to Flinders Street from Wallan, and walked the three city blocks to the studio.

The city streets would have looked like this:

Their hair would had been in rags overnight. The curls in Sarah, Martha and Emma’s hair have been successful; the others less so. All of them have a ribbon holding their hair back from their face.

The dresses are interesting. The same fabric and pattern seems to have been used for the three eldest girls. Who made them? The next three also have a similar style. All have sturdy boots and frilly pantaloons. These outfits would have been worn to church on Sundays. Did they wear them for the train journey, or change at the studio?

The only other girl, born in 1887, preceded and followed by the seven boys, was Ethel. She wrote diary entries, still held by the Wandong Historical group. Ethel wrote about the boots, which are such a feature of these little girls’ photos. “the rough track across the paddocks and hills, two miles to the little school at Wandong. In wintertime, we had to cross many flooded gullies. We wore strong boots and I was often peeved, as I compared my strong shoes with the dainty ones worn by the other girls at school.”

It was quite an expense to provide boots for so many children.

Our appetite for finding out more about this family is well and truly whetted. We plan further exploration, including an excursion to Wandong.

THREE HOLM SISTERS

These three young women, probably photographed just before the first world war are (left to right) Alfreda, Beatrice and Berta Holm. Alfreda, our maternal grandmother, was the oldest of the three, perhaps just twenty at the time. The three sisters have their long hair swept back in gentle waves, to a loose bun or twist at the back.

We wonder whether they did the white work on their shirts? We know that Beatrice and Berta spent time working in Finders Lane, doing the white embroidery known at the time as “white work”. So much we can only guess at.

They all gaze into the distance: Alfreda with a determined steely gaze, Beat with a quizzical half smile and Bert’s beautiful eyes not quite hiding her vulnerability. We can only guess, as they gaze into a future where world war is imminent.

Alfreda wore her hair long all her life. We can remember her brushing her hair at night and putting it into a long plait.

TWO COATES SISTERS

It’s hard to be a younger sister, but our mother Alice, was the fairly plain younger sister of an extraordinary beauty.

She didn’t have to deal with social media, but, when she was growing up in the 1930s, feminine beauty was important for girls.

Alice was an intelligent and able scholar, and, thank goodness, this was highly valued in her family. Her mother, Alfreda, had made sacrifices and fought for her own education. For their later secondary school, the girls were sent, at huge expense, to a city based secondary school, all the way from Croydon.

Only the wealthiest or most determined families sent their girls to school, after the age of fourteen. At McRobinson Girls’ High School, Marge and Alice were taught by, and shared classes with, the very brightest and best: future women scientists, lawyers and doctors, who would pave the way for our own generation.

But, from her school reports, we see that, while she held her own on the whole, Alice was not exceptional in that auspicious company. And she was crippled, probably her whole life, by a sense of inferiority.

And it is in their respective hair cuts from that time, that we see how the contrast between the two girls was accentuated.

When I stare at those grainy old photos, at Marge’s lush locks, and Alice’s blunt, unfashionable short bob, and straight fringe, I cannot help but ask “Why?”. Why did Alfreda allow her younger daughter to wear such an unflattering style. Why was the difference in feminine beauty accentuated and underlined so prominently by the two hairstyles? How might Alice’s life have been different, had she been encouraged to make the most of her looks, as well as her brains?

Even as they began working life, both at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory, in 1939, the difference remained. Here Marge is on the far right, and Alice on the far left. Alice is nineteen and Marge twenty-one. But the choice of hairstyle reflects very different attitudes about their appearance:

THE VICTORY ROLL

These two studio photographs of Marge are portraits of a beautiful young woman, but what does the hair tell us?

Here, a younger Marge still has very long hair, worn up now, as befitted a young woman who was no longer a child. Pretty curls and barrel curls were the look, and Marge had beautiful, wavy, very cooperative hair and was able to construct ‘the look’ very successfully.

An older Marge, maybe just twenty, posed for this studio photograph as a young woman of the war years, in the “hottest” style of the time. This photograph shows a confident young woman with a job, and presumably many admirers.

During the war, particularly during the Battle of Britain, the ‘Victory Roll’ evolved as a very popular and flattering hairstyle. The style was based on an aerobatic manoeuvre performed by pilots to signify victory. The planes would spin horizontally in celebration. The ‘Victory Roll’ hairstyle would have been difficult to execute, so hours of practice and experimentation was required. The style has stood the test of time, as it is still popular today in ‘retro’ dressing. There are many YouTube videos available with full and detailed instructions.

‘THE SET ‘

After the second world war, women’s hair fashion was dominated by ‘the set’, often a weekly set. Some women did their own at home, but others, such as our mother Alice, went to their local hairdresser.

The set involved a headful of rollers, tightly wound on wet hair, then dried under a hood dryer. This often took almost an hour, so there was time to read or chat.

Through the ages, and the generations of our family, both sexes’ hair styles have been influenced by the fashion of the day. We have all had cuts, or not. We have curled and permed and coloured and bleached, with varied results.

Today, people are not rigidly restricted to one style, as they were in the past, but have any options.

The lyrics from the musical Hair says it all: .

‘Gimme a head with hair

Long beautiful hair

Shining, gleaming,

Streaming, flaxen, waxen’

Comments

Women's Work

Like women throughout history, most of the women in our family have had the primary job of parent and homemaker. Those homes range from simple pioneer cottages to majestic residences with grand staircases and sweeping verandahs. Nearly all of those women have also done paid work. And some of those who have not been specifically employed, have had supporting roles in their husband’s careers. Some jobs have been done by different family members across different generations.

None of our women have had traditional men’s careers, but, across the generations, we have covered a wide range:

AGRICULTURE (Dairy maid, Famers’ wives)

HEALTHWORK (Doctors’ wives, Aide, Occupational Therapy Assistant)

HOSPITALITY/TOURISM (Publican, Office Administraion, Horse Trail Guide)

RELIGIOUS SERVICE (Lay Preaching and other good works, Nun)

ADMINISTRATION (Postmistress, Sales Administration Supervisor, Office Administrator)

THE ARTS/CRAFT/DRAFTING (Whitework, Semco and Dressmaking, Drafting and Drawing Office, Drafting, Drawing and Card production, Art and Craft Activities for At Risk Children, Set Design and Construction, An Artist in the Hills)

RETAIL (Grocer, Checkout Chick)

SCIENCE (Laboratory Work)

EDUCATION (Teacher)

AGRICULTURE

Dairy Maid

Our paternal great, great grandmother, Catherine Bourke, née Kelly, worked as a dairy maid in Limerick before marrying Michael Bourke, and emigrating to Australia, in 1839. When they arrived in Melbourne, their first job was managing a dairy farm in Moonee Ponds. Catherine’s knowledge and skills no doubt influenced this decision.

The “famers’ wives”

A recent (2022) Guardian article tells us that, until 1994, women could not list “farmer” as their occupation on the census form. Instead they were viewed as “non-productive silent partners”. Even today, when 49% of real farm income is contributed by women, our image of an Australian farmer is almost entirely male. This puts “farmers’ wife” in this exploration in a particular light.

Another interesting aspect of these women from our family history is the divide between the wealthy squatters and the ordinary people of the land.

Martha Rye, the “poor little thing”, whose story we told in the June 2016 post, was a “farmer’s wife”, as was her mother, Elizabeth. Both of these women had very large families.

Elizabeth, our great great great grandmother, had eleven children. We can work out quite a bit about Elizabeth from a newspaper story, written about her husband, Adam’s life. She had worked in service, as a housekeeper, before she and Adam emigrated to Australia, in 1848. She could read, but not write.

They grew potatoes and onions, first on a rented farm near Geelong, then on two acres in Broadmeadows. The whole family would have been involved in the farm work, especially at harvest and market times.

We know that Adam not only worked as a labourer on neighbouring farms, but also spent time away trying his luck on the goldfields. It would have fallen on Elizabeth and the children to keep things going on the farm.

Martha, Elizabeth’s daughter, was married to Joachim. They would have had long days on the dairy farm, Heather Farm, near Kilmore. We learned a bit about her from her daughter Sarah, born in 1866. We wrote about this in August 2016. Sarah wrote with sentimental nostalgia about milking the cows, Blossom, Peggy and Strawberry; feeding poddy calves; working the separator; and rearing seventeen children. But between the lines, one can see the massive workload.

Around the same time, our paternal great great grandparents, John and Johanna McCormack, (later called Joan) acquired their 15,000 acre grazing property, Balham Hill, fifty kilometres to the west. So, in a sense, Johanna was also a “farmer’s wife”. But what a different life! John, a Justice of the Peace, and community leader, had staff to attend to the farm. Their four surviving children all went to boarding school in the city, for their secondary education.

Two generations on, Johanna’s granddaughter, our Auntie Tish, also married a farmer, near Warrnambool. Matt Rae was probably more of a hands on farmer than John McCormick, but he, too, was considered a grazier, and Tish’s life did not run to milking cows and feeding poddy calves.

Around 1950, close to the time Tish became a “farmer’s wife”, our mother’s aunt, Beat, and her husband Bill, sold their Surrey Hills grocery and bought land for a dairy farm in Cockatoo. The activities on this farm were similar to those at Heather Farm, a hundred years earlier: milking, feeding calves, working the separator. The difference in their lives is technological. An electric milking machine and separator, tractors, hay bailers, meant that they ran a dozen cows instead of three. And they had three grown children instead of seventeen. Nevertheless, they all had to work hard to make the farm pay enough to support them all. We wrote in detail, in our November 2017 post, about our childhood visits to this farm. There we described Beat’s pigs. This was her major farming contribution. She was not just a “farmer’s wife”, but actively involved in the decision making and physical work of the farm.

Auntie Beat

HEALTHWORK

Health work does not feature much among the women in our family. There are no doctors or nurses, that we know of.

Doctors’ wives

Our grandmother, Grace, and her daughter in law, Joan, were “Doctor’s Wives”. Wealthy, well connected, pillars of society, these women had no real job. In both cases, their husband’s surgery was within their house, but they were not required to deal with actual patients.

Among the women in our family, there are a few cases of unskilled health work.

Aide

Like so many women, our mother, Alice, “went back to work” when her youngest child was about ten years old, in 1966.

The only job she had had, since leaving school aged seventeen, was the wartime munitions work she had done at Maribynong, which today would have been called Lab Technician.

What skills did she have to draw on, apart from housework and parenting?

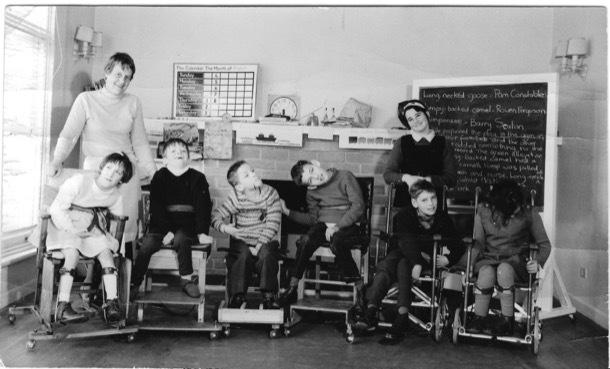

So her job as an “aide” at Lady Herring Spastic Centre was a low paid, unskilled one. She was assigned, with one other carer, to a “class” of Cerebral Palsied kids roughly the same age, none of whom had the ability to speak, and many of whom could not feed themselves. This was before the days of Communication Boards, so even the most able kids could not communicate much.

I, too, had a job at Lady Herring, after I finished school, and before I began the university year.

The centre was in Malvern, and Alice, and I, for the few weeks I was there, travelled by tram, along a very familiar route, down Riversdale Road.

There were a few qualified staff at the centre, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, but the program, such as it was, seemed to be up to people like Alice to devise. With the exception of the bus drivers, the whole staff, including the boss, was female.

The kids commuted on a special bus, and spent the whole day at the centre. Much of the time was filled with dealing with their physical needs, but there were excursions, shopping trips, walks around the neighbourhood, music sessions, and a memorable overnight “camp”. Although low status and poorly paid, it was stimulating, challenging work.

Alice with her "class"

Occupational Therapy Assistant

On the strength of my experience at Lady Herring, I did two other holiday stints as an OT assistant.

I worked with our OT friend Rikki, at Fairfield Infectious Diseases hospital for a little while. This was before HIV made it such an important place. My memories of Fairfield include the beautiful historic buildings; dozens of beds in a row, in the children’s Hepatitis ward; and the iron lung ward: people who had contracted polio as children and spent their life lying inside huge metal chambers that helped them breathe.

My job was mostly helping tidy up the activity room, and working in the ward with the Hepatitis kids: mostly bringing them things to do.

Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital

And then, during another long uni holiday, I worked at Montefiore (Jewish) Aged Care in St Kilda. It was perhaps 1970. Most of the Occupational Therapy “workers” there were volunteers: generally well off middle aged Jewish women doing their bit. One of those volunteers, who I remembered just as Mrs Hayman, later became Sue’s mother in law.

In my memory, the whole staff, except the doctors, were women.

In our centre, where the patients came to us, we ran activities like singalongs, bingo, games etc.

Many of our patients were post war immigrants from Europe, and some had been in Nazi concentration camps. It was the year that Melbourne emergency vehicles changed from sirens to “nee naw nee naw”, the same sound the SS vehicles had used in wartime Europe. When we heard the distant sounds approaching along St Kilda Road, we needed to be aware of some patients’ reaction.

I remember being told that that gentleman with his trousers barely held up with string, had been one of Melbourne’s top barristers. I still have the book called “Favourite Jewish Songs”, piano accompaniments I used for the singalongs I accompanied.

HOSPITALITY/TOURISM

Publican

Catherine Bourke, in her new home near Pakenham from 1844, helped with the establishment of Minton’s Creek Run, the farm in the Toomuc Valley, that they bought with another family. But in 1850, they bought the Latrobe Inn, on the main Gippsland Road, in current day Pakenham. Catherine moved out of the slab hut up the Valley, with her seven children, and became a publican. The inn became known as Bourke’s Hotel. Michael was still very involved with the family, and they had another eight children, but it was Catherine who ran the hotel.

As well as a stopping place for travellers, Bourke’s hotel was the local post office, and a hub for the community.

Catherine Bourke

Horse Trail Guide

Catherine’s great, great, great, great, great niece Eliza, one hundred and seventy years later, also moved to the country to start a new job in tourism. Seeking a change from office work, Eliza moved to Mansfield to work for Hidden Trails by Horseback. This company runs trails in the Victorian High Country and also at El Questro Station in the Kimberly.

In Eliza’s own words her job entailed the following:

Up at the crack of dawn. Run the horses in. Feed the ones we are working that day. Brush and saddle the horses needed for the rides.

Determine the guests riding experience, match to a horse. Sign indemnity forms, Go through basics (stop start turn etc) and then lead the ride out, float in the middle of a big group, or tail the group at the back.

We go out on four rides a day:

*AM 2 hour ride (around the station)

*Kids intro ride (around the paddock)

*1 hour loop (around a different part of the station which includes the deep moonshine creek crossing)

*PM 2 hour ride (incorporation of the 1 hour loop with a look out stop where we would take a pack horse with drinks and nibbles and tie the horses up and have a sit down)

In between those rides we feed lunch to the horses working. Then back to the stables in the afternoon, Unsaddle, wash down and tip out the horses. And then do it all again the next day. Shuffling them around in different paddocks so we could keep them all in work.

There was 40 horses total.

Long days. Great experience.

Eliza at El Questro

RELIGIOUS SERVICE

Lay Preaching and other good works

Both our mother Alice and her maternal grandmother Emma Coates (née Dau) were staunch protestants and indulged in a little lay preaching and good works.

Emma Dau, one of seventeen children, was married to Alfred Coates, who was a Wesleyan Methodist Pastor. Emma’s married life consisted of raising a family, and her duties as the Pastor’s wife. Family stories tell of her devotion to these duties and of her riding around the parish on a push bike.

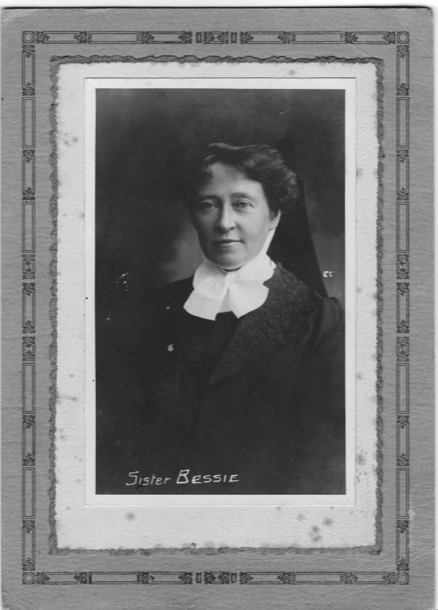

At some stage in her life, when our mother was still a child, Emma also became a Home Mission Sister and was known as Sister Bessie. As a Home Mission Sister, Emma wore an impressive uniform, that is described vividly by our mother and Auntie Marge, who as children were very impressed by this formidable woman. Here they are discussing her:

Sister Bessie

Sister Bessie worked at the Methodist Home Mission in Brunswick Street Fitzroy, in the 1920s and 30s. Sister Bessie’s work with the ‘fallen women’ and the poor, in the slums of Fitzroy was also vividly remembered by Marge and Alice. Sister Bessie’s good works involved anything from delivering babies to rescuing unmarried mothers. All of this was carried out ‘in the slums’ and in ‘poor, dirty houses’. One story has it that Sister Bessie once took off her own petticoat to give to a poor woman who did not have enough clothing.

The slums of Fitzroy were indeed slums, with a reputation for dirt, filth, disease and crime, a fearsome place. Streets were unpaved, there was no running water in many of the crowded and small weatherboard houses and children often ran barefoot.

So bad were the Fitzroy slums, that in the 1950’s they were demolished and the population was moved to the Housing Commission Towers, still standing in Brunswick Street.

Slums in Melbourne

Sister Bessie also travelled within Victoria and Tasmania. She was lay preaching, called ‘deputation work’ and raising money for the Home Mission. Apparently she was a very good story teller and must have not only impressed her young grand daughters but also her audiences, as she regaled them with stories from ‘the slums’. So impressed was one small child, that she gave up her doll ,to be given to the poor children who had no toys.

Half a century later Alice stood in her grandmother’s shoes at the same pulpit of a small, now Uniting Church, at Jung in the Wimmera.

Alice was also doing ‘deputation work’ in a fashion, preaching about world poverty and inequality. She was also raising money for the Uniting Church’s fight against poverty. Alice mentioned that her grandmother, Sister Bessie, may also have preached here. Incredibly a member of the congregation remembered as a small child listening to Sister Bessie preaching and telling stories. She said,“She was a wonderful story teller.”

Jung Methodist Church

The Nun

We grew up with stories of a nun in the family but knew no details. With the assistance of Google, we now know that Frances Bourke, [1883-1964] Jim’s Great Aunt, joined the Presentation Sisters, probably as a young woman, and became Sister Magdalen.

Presentation Convent was founded in Windsor in 1873, after a request by the Parish Priest for sorely needed teaching staff at St Mary’s school.

We are intrigued about Sister Magdalen and her role. Was she a teaching Sister or did she have another role at the Windsor Convent? Did she spend her life in the Order? Watch this space, hopefully more to come.

Presentation Sisters

ADMINISTRATION

Administration is part of many jobs, often the least pleasant part; writing reports, managing co workers, attending meetings, communication, ordering supplies, keeping records. These tasks are familiar to many workers.

Postmistress

In 1859 Bourke’s Hotel in Pakenham also became the community post office, ten years after Michael had bought the license. He became the founding post master of Pakenham. After his death, in 1877, Catherine became the Pakenham postmistress.

Up until 1901, each of the colonies operated their own postal service. After Federation, they all merged to become the Postmaster Generals Department (PMG).

Cecelia,(Cissy), Catherine’s youngest child, who never married, continued the role after Catherine’s death in 1910.

The job of postmistress would have involved taking sacks of mail to and from the Cobb and Co coach, later the train, and sorting it for people, who would come in to collect their mail.

Over time, the job of post mistress also included a savings’ bank, money order office and telegraph station; quite an important role in the local community.

Sales Administration Supervisor

But for a proper administration job, Tessa is our woman. Her job at Kenworth Trucks is to project manage the outfitting of each truck. She manages a team of people who put 22 trucks per day together, to the specifications of each customer. Keeping all the balls in the air, making sure everyone is gainfully employed, smoothing relationships with customers and between workers, maintaining records, supervising departments. It’s a very large and stressful job.

Office Administrator

Another organised young woman is Eliza who has also worked in office administration, at Nautilus Training and Curriculum, the company founded by her dad, Ian.

THE ARTS/CRAFT/DRAFTING

Whitework, Semco and Dressmaking

Three of our women worked in the textile industry, a generation apart. Both Great Aunts Bert and Beat and our Auntie Marge were involved in the embellishment of textiles with embroidery, and in dressmaking.

In our post on Auntie Bert, ‘A Sterling Character’, in March 2019 we explored ‘Whitework’. Whitework embroidery is the general term for hand embroidery worked with white thread on white fabric. It was used on many household items from babies’ bibs and tea towels to under clothes. Bert and Beat who, as young women, worked in this industry, probably worked in Flinders Lane. At this time it was the centre of the “rag trade”.

Auntie Bert, being unmarried, needed to continue in the workforce, but also be available to help her elderly parents with whom she lived. A talented and resourceful woman, she started a dressmaking business, working from home. Although self taught, her reputation for fine tailoring and expertly fitted ladies’ wear soon spread amongst the ladies of Camberwell and Surrey Hills. As her clientele increased and business grew, she had to move to bigger premises, and Bert leased space for a workroom and office in Riversdale Road Camberwell. This business is also described in our post ‘ A Sterling Character”

Drafting and Drawing Office

Our Auntie Marge worked in a number of drafting and drawing offices during her working life. After her short stint teaching, Marge began work in a drawing office in Collins Street, and then, during the war, moved to the drawing office at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory where Alice also worked. In 1941 Marge moved again, this time to the drawing office at ICI.

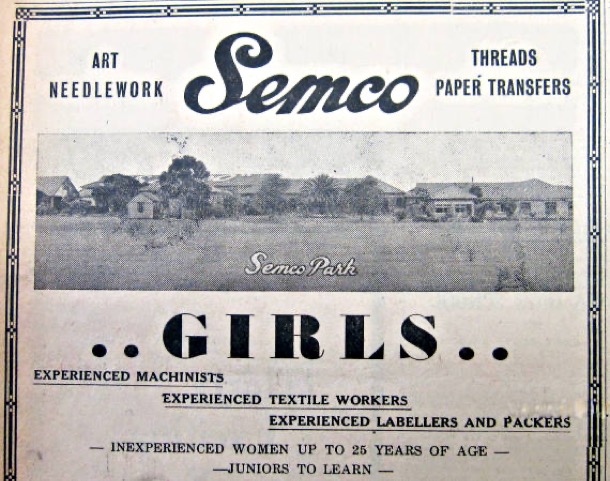

Later in life, Marge used her artistic talents at Semco, designing patterns for embroidery transfers. The designs were created as line drawings and printed onto tissue paper transfers, to be sold to women to embroider for items for the home, or as gifts. The transfers were ironed onto cloth after which the item could be embroidered accurately following the design. Margaret and I can remember embarking on an Semco embroidery project that I don’t think we finished.

Semco Workroom

Typical Semco Embroidery

Design subjects were flowers and animals, both European and Australian, cute houses, toys and even landscape scenes. Amongst the many items destined for embroidery were doilies, tablecloths and serviettes, tray cloths, handkerchiefs, babies’ outfits and children’s clothing.

Margaret and I can also remember visiting Auntie Marge at Black Rock and seeing her designs on a big drawing board. A working mother was a novelty for us, as our mother did not work outside the home.

The Semco factory and workshops located in Semco Park, Black Rock, was quite a progressive company and treated its employees well. They paid award wages to women, and provided recreation facilities for the staff, including six and a half acres of garden and lawn for their enjoyment. It was a large employer, as not only were the designs created and printed, but the embroidery cottons were also spun and dyed.

Marge worked for Semco as a part time employee, and at the same time studied Interior Design at RMIT. Both were unusual. For many women of her era, part time work outside the home was difficult to find, even once children were at school. Marge was fortunate to have Semco in her area and for it to be accessible on public transport. This allowed her to work there for many years, while pursuing her life long interest in further study.

Drafting, Drawing and Card production

Marge worked in a number of drafting and drawing offices during her working life. After her short stint teaching, Marge began work in a drawing office in Collins Street and then, during the war, moved to the drawing office at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory where Alice also worked. In 1941 Marge moved again, this time to the drawing office at ICI.

In between jobs outside the home Marge, like her Aunt Bert, started a business from home. Using her artistic skills and her design experience at Semco, Marge launched a greeting card business. She designed and screen printed the cards, packaged them and sold them to shops specialising in handmade original work.

Art and Craft Activities for At Risk Children

From this heading, it is obvious that this position could be fraught with difficulties. As a nineteen year old I was blissfully unaware of the worlds these children came from. Orana was a Uniting Church children’s home for at risk children and ‘orphans’. I remember mostly a group of cardigan and jumper clad children in skirts and shorts, traipsing into a linoleum floored space to participate in whatever I decided to do. I don’t remember anyone checking the activities, or that I had to run them past any of the staff. Some of the activities were very, very messy, but the children willingly helped me clean up. The confronting and difficult part of this job was not the behaviour of the children, but the heavy prevailing air of sadness in that place.

Set Design and Construction

Lois learnt woodworking from her dad. Together with her design and craft skills, she developed her “Top Props” business, designing and creating stage props. For instance, Deirdre’s Tappers’ concerts would not have been the amazing spectacle they were, without Lois’s colourful props.

An Artist in the Hills

Through her meticulous fine drawings and paintings Katherine explores a fantasy world inhabited by little creatures and characters, who are at home with spiderwebs and toadstools or nestled under gnarled old trees . Working from her house and studio in the Dandenongs, she is pursuing her interest in children’s book illustration.

RETAIL

Grocer

Our Great Aunt, our grandmother’s sister, Beatrice Morris (nee: Holm) owned a grocer’s shop in Maling Road, Canterbury, for a number of years. Bill Morris had previously worked at Lawson’s Grocer in Middle Camberwell , so having experience, this was a logical move. We are not sure how long they were in Maling Road but presumably Auntie Beat helped in the shop as well as raising a family of three boys. It must have been reasonably profitable, as during this time they built a house in Balwyn, and then sold the business to buy the farm, Sefton Park.

“Checkout Chick”

Anna, Beatrice’s great, great niece, is the only other woman in the family who has worked in retail, and this too was in grocery shop: the Renaissance Supermarket, Hawthorn, in the 1990’s: it was a supermarket of course. At sixteen Anna was keen to have a part time job and earn her own money. Her position was ‘checkout chick’, working on the register, before scanning of prices using barcodes was all entirely automatic. For instance, the checkout chicks had to memorise the PLU code for all the individual fruit and vegetable items, and this had to be entered on the register, manually.

SCIENCE

Laboratory Work

After the horrific use of chemical warfare (gas), on the European battlefields during the 1914-18 war, many countries began to work on ways to protect their populations from gas warfare.

Australia began its own “Chemical Defence” research program in 1926 at the Munitions Supply Laboratories, in conjunction with Melbourne Uni. They developed and assembled “respirators”.

By the time the second world war began in 1939, scientists were well advanced in this work. In 1940, over half a million respirators were manufactured at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory, and more than 500 people were employed there.

Our mother, Alice worked there, in the microscope section, testing the penetration of gas that came through the filters. When she would describe this work, she would indicate tapping and counting as she stared down the microscope. She had studied Year 11 Chemistry the year before she started.

Alice, left, working at Maribrynong

EDUCATION

Teachers

At least five of the women, in four generations of our family, have been teachers, some primary, some secondary.

The earliest we know of is our Nana, Alfreda, who taught primary school, before marrying Alfred in 1916.

She had fought for a chance to continue her education after secondary school. There was not enough money for university, and so she went to Melbourne Continuation School, which later became Melbourne High School. Its focus was teacher training and thus, after two years, Alfreda became a teacher. Presumably she taught for about four years. Women had to resign from teaching when they married.

Our Auntie Marge, Alfreda’s eldest daughter worked as a teacher for a year, straight from school. She taught 50 five year olds at Balwyn North, as a “junior teacher’. She also went to RMIT three nights a week dong Fine Art, her real passion. She only lasted one year, having decided that she was not suited to teaching. Our mother, Alice, while not actually teaching, worked as a school librarian assistant for the last years leading up to her retirement.

The next generation is ours, and at least four of us worked as secondary teachers: Pauline for a few years, and Sue, Anne and I until our retirements. All three of us did our initial tertiary education, including teacher training, on “Studentships”, which provided free education and a small wage, in return for three years service, usually in the country. Sue went to Sale, Pauline to Portland, and Margaret to Moe. Sue and and I wrote about our first year teaching experiences in a post on October 28, 2015, filed under “Young Adults 1970s”

Sale High School

Of our own daughters and nieces, only Anna has taken on the mantle of teaching. She even completed most of a PHD in Education. Recently, in her mid forties, she has gone back to the English classroom in a secondary school, where she is thriving!

Such a lot of different job experiences, and yet, within relatively narrow parameters. No astronauts, truck drivers or plumbers.

And, it must be stressed, the most important job for almost all these women, over six generations and nearly a century, is that of parent and homemaker.