Decade by Decade

Here is the audio of this from the recordings:

With our more modern education, we have less of a firm grasp of History, and we know that our children, and their children have, and will have, an even sparser knowledge. So we have taken the overview concept, explained a little more fully, and added in our father’s family history and other aspects we have recently discovered.

Alice and Marge finished recounting their family stories at 1950. One of our tasks in this project has been to continue on from then, and so we have done just that. We explore the nineteen fifties, sixties and seventies, linking what was happening in the wider world into our own lives.

1850-1950

Between 1839 and 1872 our ancestors arrived in Australia.They came from both Northern and Southern Ireland, England, Germany and Denmark. All were from humble origins, having worked as agricultural labourers, domestic servants, a baker and an engineer. Some were already married and others met here.

As our ancestors built their new lives in Victoria, the First Australians had already felt the disastrous impact of European contact. There had been violent conflict, the Wurundjeri population had been decimated and the survivors relocated to reserves or camps a ‘suitable' distance away from the growing population of Melbourne and outlying settlements. In 1844, when the Bourkes took up their selection at Pakenham, they were the first white settlers in the area and the “blacks camp” by the river was noted in Catherine’s memoir. Several years later, Adam Rye, from the other side of the family, was robbed by a party of ’50 blacks’. The newspaper report notes that ‘the blacks at this time were very treacherous’.

With the discovery of gold, in New South Wales and Victoria, there was a huge increase in population and in wealth.

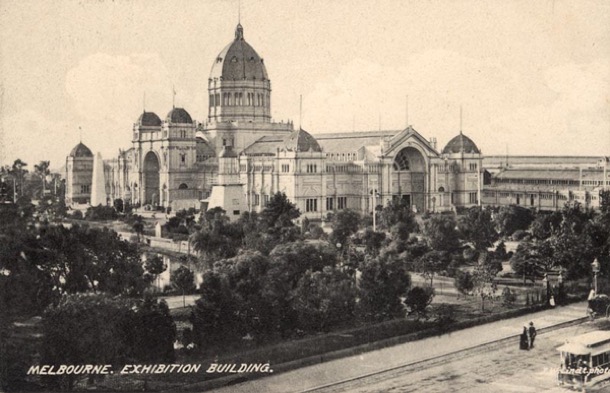

Victoria benefitted the most. Melbourne became Australia’s largest city, with a huge land boom. Grand old buildings like the Melbourne town hall and exhibition buildings are reminders of those glory days.

The increase in population, rapid development and the attraction of the goldfields led to a shortage of workers. This meant great job opportunities at every level. It also put workers in a good bargaining position.Trade Unions developed and working conditions were the best in the world. Australia was an egalitarian workers’ paradise.

Small businessmen, like publicans, bakers and lawyers, prospered with the growth in Melbourne. For farmers, it meant bigger markets, more mouths to feed. The growth in country towns, better roads and railway development made life in the country less difficult.

Engineers had a lot of work, with the sudden development of infrastructure, and property developers were run off their feet. Our great, great grandfather, a young engineer from England, was building bridges in the expanding colony. While building the bridge across the Barwon River, his son was born, his birth unregistered.

Back in ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ our grandmother’s grandparents who had arrived from Belfast, were developing St Kilda: building large houses and public buildings for those who were prospering in the boom town.

On the land, our maternal ancestor Adam Rye, who had survived the attack by ’50 blacks’, settled in Geelong and worked as a farm labourer. He was later gripped by gold fever and went north to seek his fortune, only to be held up by bushrangers and lose his meagre pickings. His daughter married a German immigrant, Dau, and they settled on a mixed farm at Wandong. Here they raised seventeen children and supplied food to the growing population.

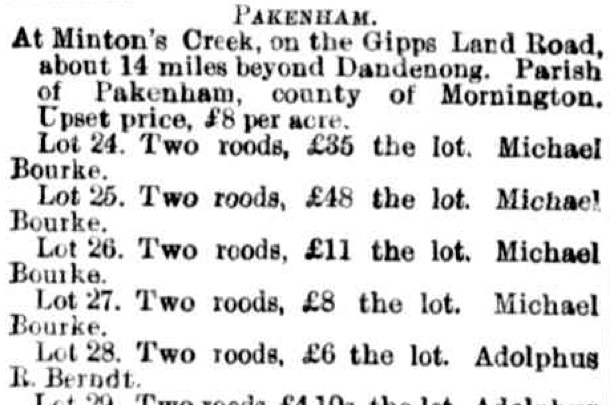

Meanwhile our paternal forbears, also on the land, were making their mark in Gippsland and North Central Victoria. In Pakenham the Irish Bourkes were building their family of thirteen children, and now owned Bourke’s Hotel. They were becoming significant landowners and community members, as they set about acquiring land, marrying their daughters well and establishing their sons on large and prosperous properties. They also served their community in local Government and built the horse racing industry in Pakenham.

1858 Land Sales, Michael Bourke's purchases:

The McCormacks and Hamiltons, in North Central Victoria were also acquiring and working large grazing properties, in the Goulburn Valley. They too were pillars of the local Catholic Church and community. Our grandmother was born at Balham Hill, at Molesworth, pictured below.

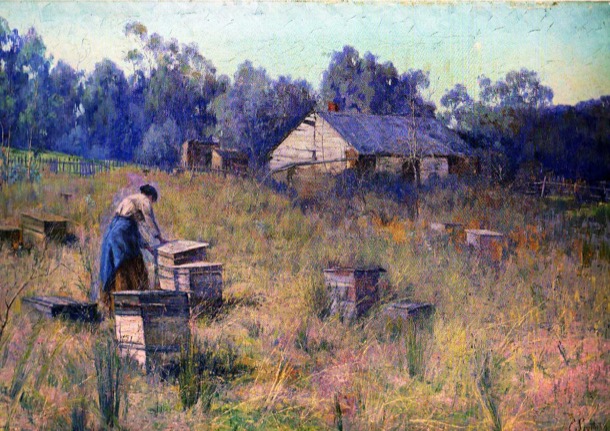

Melbourne became the financial centre of Australia and New Zealand. The Pakenham Bourkes’ fourth son, our great grandfather, was part of this world. He had moved to Parkville and built his law career in this thriving city. Australians were growing in confidence and the young nation was showing signs of an interest in its own identity. This was the era of Henry Lawson and Banjo Patterson, who wrote about the characters of ‘the bush’. At the same time, Tom Roberts and his paintings glorified the unique Australian landscape and the men and women who toiled there. This growing sense of identity and of nationhood is reflected in the moves for independence from Great Britain. During this era of optimism and hope our grandparents were small children, and their families were well established in both country Victoria and Melbourne.

Federation was achieved in 1901, and the country celebrated:

Australia was longer a colony but an independent nation. Melbourne was the largest city in Australia at the time and the second largest city in the Empire (after London). It was fitting that the new Parliament should sit in Melbourne while Canberra was being constructed.

The decade after Federation saw Australian women join the battle for women’s suffrage. White men over 18 in Victoria had had the right to vote since 1858, but women were not granted this right until 1908. Our maternal grandmother, Alfreda, was sixteen when women were granted the right to vote. We imagine she would have approved. She had been engaged in her own battle to pursue her dream of further education; and during this decade she finished her secondary education at Melbourne’s Continuation School, the opening of which marked the beginning of state secondary education in Victoria.

This period of prosperity, optimism, and political and social change ended in the devastation of the Word War 1. We know little of the family’s war service, but three of our maternal grandfather’s uncles served in France, and one lost his life. In the highly charged patriotic atmosphere of the time, and with mounting casualty lists, the war years must have been a difficult time, especially for our grandfather who was considered unfit for service due to ill health. He was deeply upset when given a white feather. Presumably our paternal grandfather being a country doctor, was in a protected occupation.

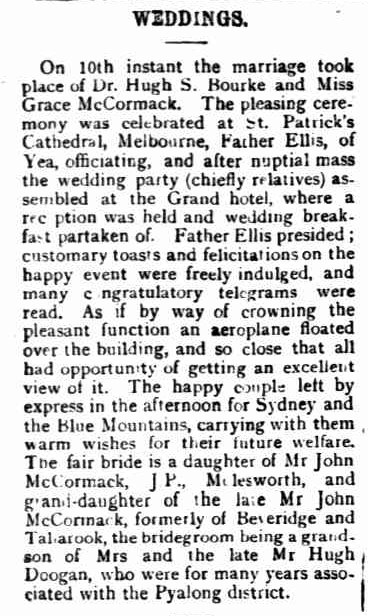

Our grandparents were all married at the end of this war. Our father’s parents were married in St Patricks Cathedral in a grand affair. Grace and Hugh then settled in Koroit in the Western District, where Hugh was the local doctor.

In contrast our mother’s parents were married in the Methodist Church in Surrey Hills in a small and simple ceremony where the bride did not even wear a wedding dress. At that time Alfreda was working as a teacher and Alf was working in a hardware shop in the city. They also moved to the country, soon after: to Eildon, where hardware supplies were needed for the construction of Eildon Weir.

Our family then lived through the Great Depression of the thirties, formative years for our parents who were by then at school. Our father was boarding at Xavier College and our mother was at Croydon Primary School. By the end of the decade the world was at war again.

During the war in a munitions factory, in Maribyrnong, two very different family histories were to merge into one. One was Irish Catholic, successful and quite wealthy, and the other was staunchly Protestant and relatively poor. One was involved in the Melbourne horse racing scene and the other was teetotal and interested in ideas and the new ‘isms’ that were emerging on the other side of the world. Our parents were married at the end of World War 2.

1950s

Our mother’s view of the 1950s, in her recording, is of a time of burgeoning economic growth and development. To us, it is the decade we first became aware of the world.

Our world was redolent with Australiana, but we were intensely aware of our British heritage, and it dominated our reading, our schooling, our whole culture. A portrait of The Queen hung in our school. Sue remembers keeping a scrap book at home of magazine articles about the Royal Family. She was particularly interested in the corgis. Apparently I had one too, and it contained very many pieces about Princess Margaret.

Enid Blyton Books:

Globally, it was a dangerous world, with the cold war in full swing, and a very real threat of nuclear war. Our parents had quite well developed political opinions, particularly our mother, so we were exposed to adult conversations about the issues of the day. Family friends and neighbours, the Lees, were active in the union movement. They encouraged our parents’ involvement in the movement for “unilateral disarmament” and other left wing activities. I remember our mother’s admiration for an older couple who took a small boat out into the Pacific Ocean to protest the nuclear testing. Bikini Atoll in the Pacific, sixty years on, is still a no go zone from the USA nuclear tests carried out there up until 1958.

This was the time of McCarthyism in America, and Australian political attempts to ban the Australian Communist Party: a divisive time, where everyday people had strong opinions one way or the other. Sue remembers Prime Minister Menzies as “the devil incarnate”.

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament became overwhelmed in the 1960s by anti Vietnam War action, but it was an important political movement of the 1950s. The familiar “Ban the Bomb”, or “Peace” symbol was invented in 1958, as a symbolic representation of ND (Nuclear Disarmament)

Our family was, by today’s standards, quite poor, but this did not impinge on our life, at this time. We were well fed, we had a stay at home mother who looked after us and the struggle to pay bills was not part of our conscious experience. As far as we children knew, we were neither poorer nor better off than our neighbours, with the exception of the family in the housing commission house nearby, whose son had polio and who didn’t always have enough to eat. The world, as we observed it in our daily life, was largely classless. Perhaps Australia at this time really was the egalitarian workers’ paradise it purported to be, to prospective migrants in Britain. (only whites of course)

Nevertheless, we knew about the religious and economic differences within our family: that our father’s relatives were wealthy and that we were not, because our parents’ union was a “mixed marriage” and very disapproved of. We were very aware of their Catholicism and our Protestantism, and that we were not as close to our grandmother as our cousins were.

Our father during the 1950s, went from working as an industrial chemist by day, and studying by night, to full time teaching. We got our first car, a television and a refrigerator. By the end of the decade there had been four children born. It was busy, but simple life, encumbered by very little “stuff”.

Our suburb of Box Hill South was the edge of suburbia, when our parents first bought their block. During the fifties the new suburbs filled in with more and more families, and the frontier stretched east towards the orchards of Blackburn.

Below is Doncaster, contrasting the 1945 view to that of today. It was little changed in the 1950s. We remember breaking an axle on our Talbot car in Doncaster, a farming and orchards area with narrow unmade roads.

The sewerage reached us during the late fifties. Neighbours got together to dig each others’ trenches. The footpaths were paved, allowing us to roller-skate along them.

The streets were deemed to be safe enough for five year old girls to walk unsupervised, from Box Hill South to Surrey Hills to Sunday School and to Bennettswood to school.

We are baby boomers, and this was the most booming time. When we began school, Sue in 1954 and me in 1957, “temporary” schools were being thrown up, and unqualified teachers recruited to deal with the rush.

My first experience of school was a few weeks in “bubs”, and then the-bursting-at-the-seams class was reduced by a handful of us being put straight into Grade 1. Here is that grade photo with Miss Meadows and her 47 pupils.

1960s

This decade covers our teenage years. It was a time of huge change in the western world. By the end of the decade, Neil Armstrong had walked on the moon, women were controlling their own fertility with the Pill and popular culture had discovered the huge Baby Boomer teens market. During the sixties, there was a general loosening and questioning of traditional social norms. Older people were probably more aware of these momentous changes. For us the loosening of the cultural apron strings, that is such a feature of these times, coincided with the loosening of our familial apron strings.

The conflict between our generation’s straining at the bit and society’s entrenched traditional values played out in our school life. As fashion hemlines rose, school uniform strictures fought them. We knelt to have the gap between our uniforms and the floor measured precisely, and hastily pulled down our hoiked up dresses whenever a teacher came in sight. The anti war slogans on our pencil cases, alongside the names of pop groups we fancied, had to be kept hidden, or there would be detention. A new rule dividing the grassed hill area into a boys’ side and a girls’ side transformed the hill into a vast empty space with a cramped central area where everybody sat alongside the invisible line. In our school, as far as we can remember, there were no brown faces, hardly any Asian faces and no Aborigines. Foreigners were the Italian and Greek “new Australians”, and even they were rare in our (then) outer Eastern suburb.

Culturally, as more and more families spent more and more time around the television set, American culture rather than English, began to dominate our life.

We can’t remember exactly when we got a television set, just that it was bought specifically for watching cricket. As a family we watched the Australian serial Bellbird, which preceded the seven o'clock news. There were a succession of American sit coms we all watched, like My Favourite Martian, Bewitched, Father Knows Best, the Donna Reed show, Bachelor Father, My Three Sons and Mr Ed. After school I remember Clutch Cargo, Sea Hunt, George Reeves in Superman, and Hogan’s Heroes, F troop and Bonanza. And very rarely we were granted permission to watch 77 Sunset Strip. These are nearly all American titles. There were Australian and English shows too, but it is the American ones we remember.

With this American influence in our lives, and increasing prosperity, “teenagers”, a term first heard in the 1950s, emerged even more as a marketing target. For the first time, teenagers had their own music, fashion, language. I was more plugged into Teen culture than Sue. I began to go to local Saturday night church dances from about aged 14. There was always a live band who played rock and roll covers. A group of us from church would go.

Dress was quite formal, ties for boys and stockings and heels for girls. I remember the winter that plain coloured wool dresses with white crocheted collars and cuffs were all the rage: probably 1965. Auntie Bert, dressmaker to the wealthy ladies of Melbourne, made me a tailored aqua one with little kick pleats around the bottom.

Below is fourteen year old Margaret in the aqua wooden dress with while crocheted collar and cuffs.

During the 1960s, Australians were entrenched in the divisive Vietnam war. Our family was by default anti war, and the “all the way with LBJ” policy of our government was fiercely criticised. In 1967, my boyfriend and another close family friend was conscripted for military service. Against huge opposition, the government had voted to call up into military service some twenty year old men. Many of them ended up fighting in the jungles of Vietnam. Our mother testified in court for the other friend, who was a registered conscientious objector. But many other friends and acquaintances went off to Vietnam with their hair shaved and very basic training. Some of those veterans live with the trauma of those experiences even today.

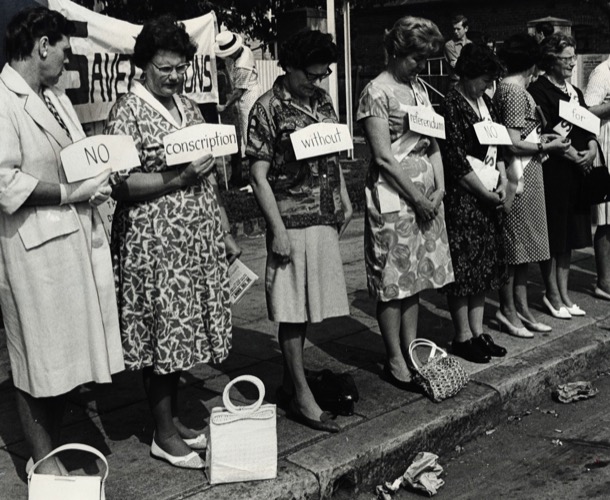

A "Save Our Sons" movement protested against conscription:

Gradually, public opinion in Australia, as in America, swung firmly against the war; and ordinary Australians demonstrated in the street.

By 1970, Sue and I had left school and were engaged in our tertiary studies, sharing a house in North Balwyn. University was still expensive, and we both managed it by gaining a bonded scholarship called a Studentship, which paid our fees, as well as a small living allowance. Even in a relatively enlightened family like ours, it was made clear that any family budget that was to be spent on university studies, was to be saved for our younger brothers, because they were boys.

1970s

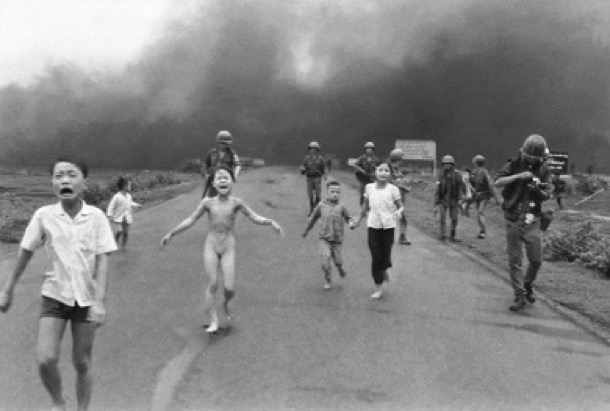

The 1970s was a decade of change for us personally, and a tumultuous time worldwide. In some ways, the decade was a continuation of the 1960s. Women, gays and lesbians and other marginalised people continued their fight for equality, and many Australians joined the world wide protest against the ongoing war in Vietnam. Outrage at the continuing conflict was fuelled by the graphic coverage of the brutality of war, available nightly on our TV screens.

Protest was bitter and violent.

By 1975 Saigon had fallen: a humiliating defeat for the USA.

There was more violence as Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge murdered 1.7 million Cambodians, and on the other side of the world, the IRA fought for British withdrawal from Northern Ireland.

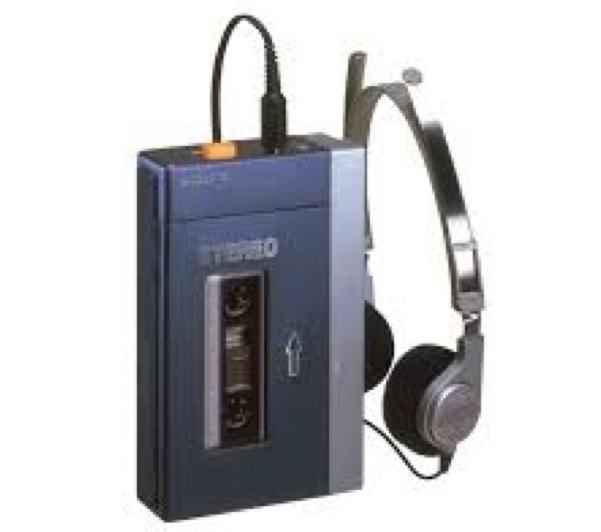

Rapid advances in technology were in play, changing our world and planting the seeds for the creation of digital world, we are grappling with today. Apple launched the Apple 1, a desk top computer, pocket calculators were commercially available for the first time, and music became mobile with the release of the Sony Walkman.

In the popular music scene, Elvis Presley died, the Beatles split up, the Sex Pistols band recorded an album and disco music took the world by storm.

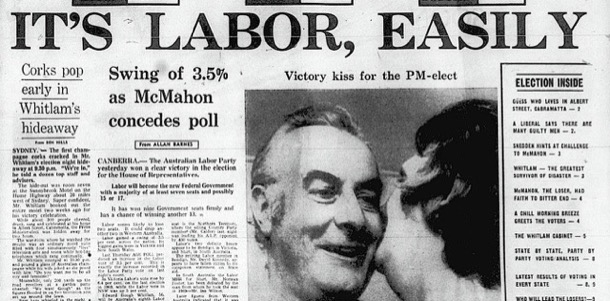

In Australia, at the beginning of the decade, Gough Whitlam led the Labour Party to victory in the 1972 election. This ended twenty-three years of unbroken Liberal-Country Party Coalition government.

Change was inevitable and rapid: the troops were brought home from Vietnam; educational reforms were introduced, such as free University education; and Whitlam visited the feared red menace, Communist China. Inept financial management, scandal and the rate of change contributed to another landmark event now known as, The Dismissal. Whitlam was sacked by Kerr, then Governor General.

Gough Whitlam stood on the steps of Parliament House and declared “Well may we say ‘God save the Queen’, because nothing will save the Governor- General”:

The Liberals returned to power under Malcolm Fraser. For Labour supporters like us, it was a bitter pill.

Waiting in the wings was Bob Hawke, who was both President of the ACTU and President of the Labour Party. The 1970s ended with Hawke deciding to enter politics. He was elected as the member for Wills in the 1980 election and Labour was once again in power. The 1980s in Australia was Hawke’s and Paul Keating’s decade. The reforms they ushered in changed the face of Australia: we thought for the better.

At the beginning of this tumultuous decade Margaret and I were fancy free. We moved out of home, sharing a house and living on our teaching studentships, as university education was not yet free. Margaret supplemented her income, paid $1 an hour, working at the first fast food outlet in Bourke Street. Working the late shift posed no danger as the Derby closed about 11 pm [very late] and Margaret was able to walk out to her Morris Minor parked right outside the restaurant. “It was always easy to park in Bourke Street, there were lots of parking spots,” remembers Margaret. It was such a different city then. We also embarked on our teaching careers. I began my teaching career in Sale and Margaret at Moe.

We had wonderful camping holidays, often in the Snowy Mountains; we saw interesting alternative movies at the Walhalla picture theatre in Richmond; we went to Sydney on the train to see Hair and saw nudity on stage; so risque! We listened to the Beatles, The Seekers, Cat Stevens and Peter Paul and Mary amongst others, on vinyl of course.

Margaret had begun teaching at Moe in 1973 and Jono and I, after a year overseas, both taught at Drouin High School, quite nearby. By the end of the decade, I had given up teaching and was at home at Gowar Avenue with a three year old Anna. Margaret was teaching at Croydon and was living in Gully Crescent with Ken.

Conclusion.

Marge and Alice finished their oral family history with their weddings and the end of the Second World War. It was neat: 1850-1950. It left off when they were both about thirty, settled into the business of raising children.

We are finishing our own overview at the corresponding stage. For us, this is 1980.

In the very last minute of the recording Alice, by herself for this part of the process, reflects on the speed of technological change that she and Marge had witnessed in their lifetime.

“But there’s a sort of corresponding suddenness in those new technologies and we tremble, as we think you do too, at what the outcome of all this is going to be for your children.

So looking back over that hundred years, we see this period of rapid, strong and significant development: a development that began gently enough, but now, in 1990, is rushed and killing and devastating.

And we look forward into the future for you and for our grandchildren as a time where perhaps you will learn what de-development is all about, and maybe the graph is going to go gently and firmly and calmly for you, into a period that is not as frantic as the one we’ve lived in.”

Strikingly and shockingly, the suddenness and the devastation she speaks of in 1990 has not diminished, but increased. And now, in 2018, as we watch our own grandchildren navigating their way into the world, we too tremble at what the outcome of “all this” will be.

How to Rescue the World

ALF AND ALFREDA

Marge and Alice in their family history tapes, discuss Alfreda’s political and philosophical bent. The setting is Croydon in the 1930s. Croydon is a country town and it is the height of The Great Depression. Alf is working long hours at the Croydon Timber Yard and the family sell milk and cream from their cow. Many of their neighbours are unemployed, and homeless men come to their door to ask for work or food. In Germany, Hitler’s Nazi party is beginning to show its true colours and Russia has been a republic for less than twenty years. Alfreda is consumed by the great ideas of Politics and Economics. She shares this with Frank Hibbert, the Croydon Primary School headmaster.

Alfreda’s friend, Frank Hibbert was a progressive educator who shared her political views. His influence on the young Marge and Alice was profound.

There are also signs of early environmentalism in Alfreda’s letters. On January 16th 1935, she and Alf are camping at Yellingbo, by the creek in what is now the protected area for the Helmeted Honeyeater. She writes to Alice:

Yesterday was a beautiful day and in the evening just after sunset - oh! I wish i could tell you or show you how beautiful the bush was - for half an hour. What God has given us is so beautiful, but don’t humans muck things up - an ugly fence, a cigarette butt, an old piece of lolly paper thrown down. an old pair of shoes - everything we touch seems ugly after that beauty that I saw last night- even our bodies haven’t the beauty and grace of the wild things….. I’ll see we don’t disfigure God’s beautiful bush when we leave this lovely spot.

And later, in 1946, Alf gives us a taste of his own strong sense of social justice. He is visiting Marge in Sydney and has just received the news that Alice and Jim have managed to buy the block of land in Box Hill South that became our family home. He writes:

Your news about your block of land caused quite a lot of excitement in the family circle. Our own few square feet of land is of great importance in our lives. At last we are the possessors of what really amounts to an inheritance - a small portion of God’s earth which we can call our own. It was ordained that each man should have his share of good earth; but man overruled God’s laws and made his own, thereby making it easy enough for a rich man to obtain all the land he wants to, but placing every obstruction in the path of the poor man to obtain that which is morally his own. It is only when people, like you two, scrape to save the wherewithal, that you get your share, or rather, a very small portion of it. But I must keep off my pet theme.

ALICE AND JIM

This was the value system that Alice, our mother, has passed on to us. We were never in any doubt about which side of any particular issue was the correct one.

Margaret and Alice at the Moore Street kitchen table

Both Alice and Jim, our father, were staunch Labour voters, and had a strong commitment to social justice.

The world’s first atomic bomb was detonated in Japan in 1945, followed by a nuclear arms race between the USA and the USSR. Bombs were tested, and people felt that there was a constant threat of war breaking out again. Alice and Jim and a like-minded couple from our street were involved in the call for unilateral nuclear disarmament. Another neighbour, Judah Watten, a writer and a communist, was also a member of this “leftist” protest group. This was the time of anti communist McCarthyism in America, and Jim and Alice’s actions were quite radical.

Alice became more confident and able to hold her own in conversations over these years. There were many discussions around our Moore Street kitchen table about the social or political issue of the moment.

Christian social justice became her main focus during her fifties and sixties.

She was active in a number of left wing church organisations. I remember in 1975, when I was living in the country, listening to her talk on the radio about third world poverty. Even in her later years, blind and housebound, she would listen avidly to the radio and talk about politics to anyone who would listen.

Of Jim, we have fewer memories. We remember marching with him in a teachers' protest on the issue of State Aid to private schools. We are now quite used to Governments providing money to private schools, but, when first mooted by the Menzies Government, it was greeted with outrage by many. One of Jim’s concerns during the march was that he would appear on the television news and be seen by his conservative, Catholic, Liberal voting mother.

Jim was a member of the Board of Management of our family’s church, St James, Wattle Park. He was outraged when he discovered the cost of the new church building. He resigned over the issue. In his view the money would have been better spent elsewhere. This is evidence of the strength of his principles, as his role in the church was important to him.

SUE

My memories of my early twenties and engagement in ‘protest’ is of the outrage of youth. ‘How dare they!’

During my last year at College and my first years of teaching, the VSTA, the union representing secondary teachers, was very active in a campaign to improve teaching conditions. I had had an early introduction to strike action by teachers when Margaret and I marched with Dad over state aid to non government schools so I was an eager participant in the ferment.

In outrage that the State Government would contemplate increasing class sizes and teaching allotments, a couple of friends and I formed a VSTA branch and began conducting meetings. I remember calling a strike meeting and organising a boycott of classes that we were convinced would change the world. It didn't! Fancy that! We were still fighting this battle during our first years of teaching.

A much more serious concern was the Vietnam War that the US had been involved in for years and, unbeknown to the public, so had Australia! Prime Minister Menzies had mislead the Parliament and the public, and had committed Special Forces to fight in Vietnam. His successor, Harold Holt, invoking the ANZUS Treaty, upped our level of support and, as the war dragged on with no victory in sight, National Service or conscription was introduced. My family and friends were all very much against the war and the deceptive and high handed action by successive Liberal Governments. Outrage and protest was a consuming passion.

It was sometimes a bit scary! In the early days before the huge moratoriums, the numbers protesting were considerable but not large, and the police seemed to be a threatening and sinister presence. I remember the July 4th 1967 protest outside the American Consulate in St Kilda Road. I went to this one with Mum and Margaret.

It was dark as we arrived and stood with the other protesters outside the closed front gates to the Consulate. There was no visible presence in the building, as we held our anti-war banners and chanted slogans. The most sinister aspect was watching the police buses pull up across the park and disgorge many, many policemen. I remember thinking, ‘Can this be Australia?’ A noisy and highly visible minority of the protesters were quite confrontational and aggressive and were consequently arrested. We stayed well clear of the action but it was hard to avoid the police horses. They are enormous up front and personal, and were used very effectively to nudge the crowd away from the gates. Overall it was a very sobering experience and one that has stayed with me. We live in a democracy with the right to protest peacefully. What must it be like protesting under less benign circumstances?

After these small beginnings the protest numbers swelled, culminating in the euphoria of the Moratorium Marches that brought cities across the world to a standstill, including Melbourne.

The ABC captures the spirit and the times better than I can. Have a look:

http://www.abc.net.au/archives/80days/stories/2012/01/19/3411534.htm

Even though I may have wished for many thousands to take to the streets again, as they did in the Moratoriums, it has not happened on such a scale, but here’s hoping!!

The demonstrations against the Vietnam War left a profound legacy. After such a powerful and successful protest movement, it seems the natural response to feelings of outrage: paint a banner and march! As Margaret says, ‘It is part of democracy’. Aren't we lucky!

Therefore, along with thousands of other concerned people, I have attempted to ban nuclear weapons, stop the war in Iraq, stop logging of old growth forests in Tasmania and East Gippsland and persuade our government to take action to reduce emissions.

The world has changed, but not always for the better. Today, as well as the kitchen table, the letter, the banner and the march, we have at our disposal the power of global and instant communication and social media. It is the era of Get Up and ’Clicktivism’.

Sue and Margaret protesting together at Tecoma

MARGARET

July 4th 1967. It is winter in Melbourne and it is raining. The puddles flash …blue…black…blue…black…

“Link arms!” call the young bearded marshalls running up and down the line of marchers. We are marching on the American Embassy, protesting atrocities in Vietnam, pressurising our government to change their “All the way with LBJ” policy. Police horses charge the crowd. One of my companions, my forty-three year old mother, loses her handbag.

Five years later, a New Yorker I go out with a few times, assures me that there would have been fully armed Marines in the embassy, and that they wouldn’t have hesitated to shoot, had we successfully “stormed” the building.

This was my first real “demo”. I don’t remember why it was just my sister, my mother and I there. I was fifteen.

Over the ensuing fifty years, I have waved banners demanding many things: the end to the logging of old growth forests and the creation of National parks; that uranium be left in the ground; that there be land rights for our indigenous populations; smaller class sizes; a fairer allocation of education funds and more of them; that we not go to war and/or bring our troops home; that the public service not be decimated by cuts; that the separation of power between the judiciary, the legislature and the executive be maintained; that MacDonald’s stay out of our Hills community.

Most recently I marched with Michael and Chris to urge our planet to act on Climate Change:

Marching for climate justice... a family affair

The thread that links these causes, is the same thread that runs back to the 1930s around the Coates’ dinner table in Croydon. It involves words like environment, justice, democracy, fairness, equity, peace, kindness and conservation.