War Service

Our family stories research has led to the discovery of four great great uncles: four brothers who were soldiers. They were four of the seventeen children of Martha and Joachim of Heather Farm in Wandong, about whom we wrote in "The Poor Little Thing" on June 8th, 2016 and "Heather Farm" on August 3rd, 2016. Our maternal grandfather Alf, was their nephew.

Learning their stories, imagining their experiences, fitting their details into the wider sweeps of military history has been enthralling and rewarding.

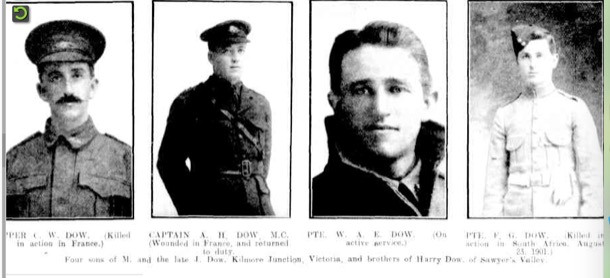

We present the four Dau (Dow) brothers, Frederick, Arthur, Charles and Walter.

Frederick and Arthur actually enlisted as Dow, an anglicised version of Dau. It is a constant confusion.

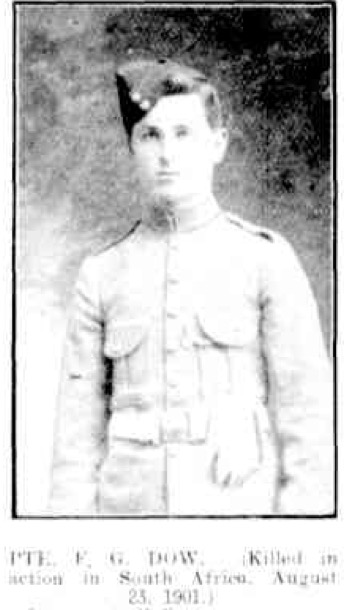

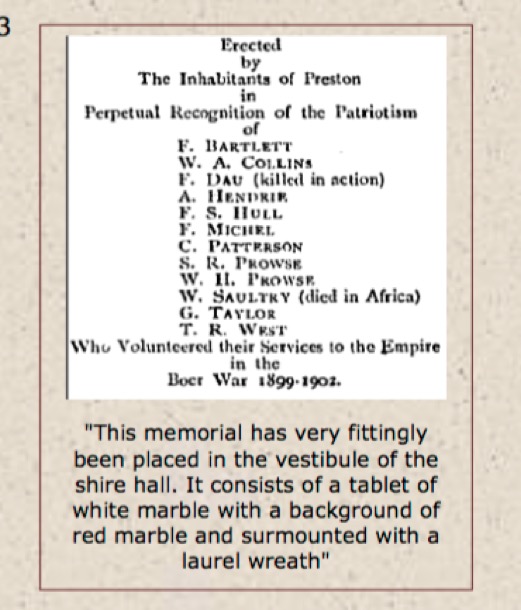

PRIVATE F. G. DOW

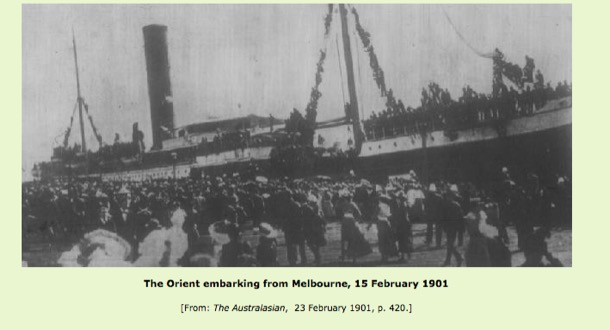

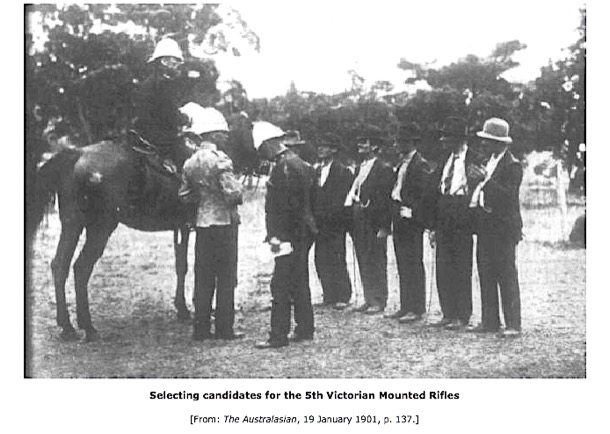

Australia was twenty-eight days old when nineteen year old Frederick sailed on The Orient out of Melbourne, bound for South Africa and the Boer War. His company was the Fifth Victorian Mounted Rifles.

Britain had colonised the southern part of South Africa eighty years earlier and had had an uneasy relationship with the other colonisers of this area, the Dutch Boers, who had been there for a hundred and fifty years longer. Tensions had escalated to war in 1899, and the British Empire was required to send troops to participate.

By 1901, the war had become a drawn out guerrilla affair mostly in the desert-like Transvaal area with small groups of Boer soldiers attacking and then disappearing back into the harsh dry landscape.

Many of the “colonial” troops, like Frederick were bushmen, tough, self reliant and skilled at shooting from horseback: exactly the set of skills needed for this type of warfare. But it was very hard on men and horses alike. Most of the fighting took the form of small skirmishes, but sometimes the men had to attack remote farmhouses, confiscate the livestock, destroy the farms and escort the women and children to the notorious concentration camps where thousands died. R G Keys of South Moorabbin wrote of making captures of large numbers of prisoners and cattle and having brought in large numbers of Boer families. “We have also burnt thousands of acres of grass and a number of farms and have destroyed everything of any use to the Boers.”

They spent long periods in the saddle with few opportunities to bathe or change their clothes; lice were a constant problem. Temperatures on the veld ranged from relentless heat during the day to freezing cold at night.

Private F W Collins wrote, “What I can see of the war is that the Boers can keep it on as long as they like, the only way is to starve them out. They get right in the mountains, and there are bullets whizzing about you and you cannot see any enemy. We are going from daylight till dark, up at 4 o’clock in the morning, and it is sometimes midnight before we get in again, so you can imagine we feel quite knocked out. When I get back to old Victoria I’ll do nothing but sleep.”

We don’t have much detail about Frederick’s death, but Lord Kitchener, Field Marshall in charge of the war, reported in one of his dispatches: "on the 23rd August Lieutenant Colonel Pulteney had a sharp engagement with the enemy on the west side of the Schurveberg, in which the Victorian MR (Mounted Rifles) had 2 men killed and 5 wounded.” One of those two men killed was Frederick Dow.

Two years later, his mother, Martha, and brother Harry inserted this memorial in the local paper:

In loving memory of dear Fred, who was killed in battle near Vryheld, South Africa, August 23, 1901; aged 19 years and 6 months.

Tis two sad years ago today,

The trial was hard, the shock severe,

To part with one we loved so dear.

He is gone, but not forgotten,

Never shall his memory fade;

Sweetest thought shall ever linger

Round about our soldier’s grave.

MAJOR A. H. DOW

Arthur was on one of the first ships to leave Melbourne for the war. He sailed from Station Pier Melbourne on the Orvieto on October 21st 1914. There were huge crowds to wave off this first wave of volunteers.

Soldiers from the Orvieto disembarking at Egypt:

Arthur was a career soldier. He had joined up as a military engineer, aged seventeen in 1908 and had already been promoted to Warrant Officer.

Like all of those first soldiers, after a short time in Egypt, Arthur was dispatched as part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force to what would become known as Anzac Cove, Gallipoli. He was there for the very first Anzac Day landing, but went ashore “several days” later. He must have watched from his ship as the first few waves of shore boats struggled amid Turkish bullets and shells that rained down from the cliffs. By the time it was his turn, things were still very chaotic and dangerous. It took ten days for the troops to be safely dug in.

On June 16th, he was Injured and was treated at the hospital on the Greek island of Lemnos.

He went back to Gallipoli ten days later.

At the beginning of August, Arthur was detached for duty to Assistant Adjutant General 3rd Echelon in Alexandria (which dealt wth military discipline, though he was in the “records section&rdquo![]() .

.

By March 1916 he was with the Fourth division engineers at the huge Anzac training area near Cairo, called Tel-el-Kebir, a six mile long “tent city”, where he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant.

He must have participated in the notorious three day march across the desert in searing heat to Serapeum, on the Suez Canal.

Here there was more training, in preparation for the move to France, and he was promoted again to Lieutenant. On June 2nd, he travelled on the ship “Kinsfaun Castle” to Marseilles, in the south of France.

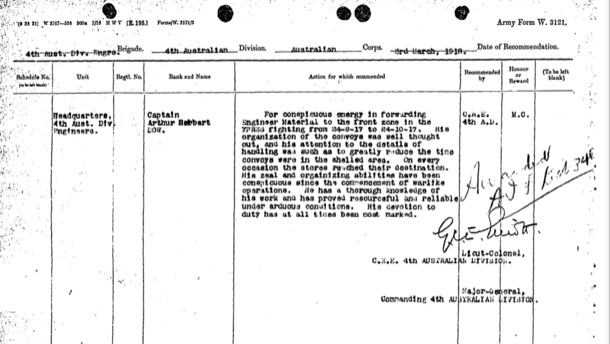

The next mention in Arthur’s record is six months later, in January 1917, where he is “mentioned in despatches” (a sort of honour) and then again on June 26th, where he is promoted to Captain.

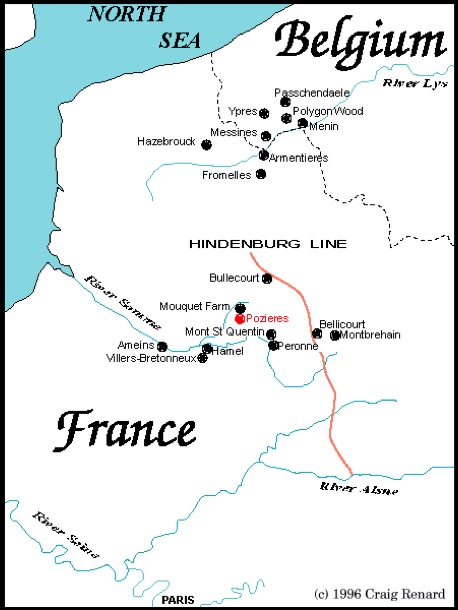

We know what he was involved in during those couple of years in France and Belgium because we know what unit he was in.

He fought at Ypres and Messines Ridge and Passchendael: all infamous places in the history of the first world war.

It was for his work from 24th September through to 24th October that he was awarded the Military Cross.

Arthur was a military engineer. Engineers, also known as sappers, were essential to the running of the war. Without them, other branches of the Allied Forces would have found it difficult to cross the muddy and shell-ravaged ground of the Western Front. Their responsibilities included constructing the lines of defence, temporary bridges, tunnels and trenches, observation posts, roads, railways, communication lines, buildings of all kinds, showers and bathing facilities, and other material and mechanical solutions to the problems associated with fighting.

At the time Arthur won the Military Cross, the 4th Division was involved in the battle of Polygon Wood and then the third battle of Ypres, Passchendaele. It is from the Ypres-Passchendaele area that we get the iconic images we have of trench warfare in a landscape of deep mud and water filled shell holes with broken off toothpick trees, stretching away into a hazy distance; where falling off the duck board paths meant drowning in mud. By the time Passchendael was captured in November 1917, the Australians had fought for eight weeks and suffered over 38 thousand casualties.

At the beginning of December Arthur had a fortnight’s leave in Nice, Italy and on his return he was sent to England to Brightlingsea to train engineers. It must have been a welcome break, but he was back in France by May, 1918.

He was wounded in action on August 8th. At that time his company, the 14th Field Company Engineers was laying wire barriers across the area to be advanced upon in front of the village of Villers Brettoneux. They were harassed by constant German shellfire, and snipers.

The resulting battle was called the Battle for Amiens, and was a resounding success, although between August 7th and 14th, the Australians lost six and a half thousand men.

Arthur left for Australia on September 27th, and within six weeks the war was over.

He remained in the services for a few years. In 1920 he had a few months’ successful treatment for “depression and irritability”. On his application form, where he had to provide supporting evidence for his entitlement to this help, he wrote a single word: “Anzac”.

By 1940, one year into the second world war, Arthur, who had been working in a Government desk job in the civil service, rejoined the army as a Major. He was 49, married with two children, and living in St Kilda.

His war this time, was fought at a desk, sometimes in the Middle East and sometimes back in Australia. His war record mentions positions like “Hiring and Claims”, “Accomodation and Quartering”. He left finally in October 1945, aged 54. During this time he had treatment for an affected patch of skin in his mouth. The doctor mentions that this is the spot where Arthur’s pipe customarily sits.

The last mention of Arthur in the war record is application for repatriation consideration for a minor health issue. He was a healthy 72 and living in Boronia.

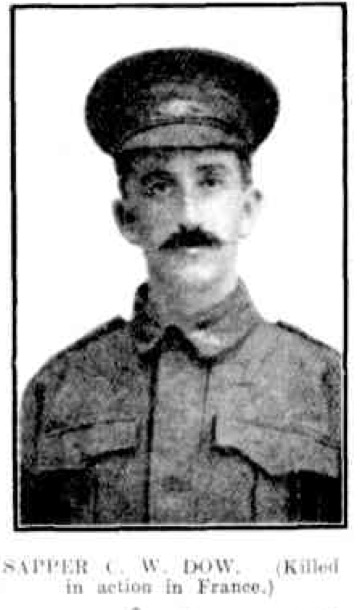

SAPPER C.W. DAU (DOW)

Like his brother Arthur, Charles enlisted as a sapper, or military engineer. He joined up in February 1916 in Hamilton, where he had been working as a railway “ganger”. He was thirty, slim, fair haired and blue eyed and was married to Edith, who was still back in Wandong with their three children.

He left for Europe in April and by October had joined the Second Division in Belgium, before marching to the Somme area in France. His division was involved in attacks on a collection of German trenches known as The Maze,

The main Somme fighting came to an end on 18 November in the rain, mud, and slush of the oncoming winter.

Over the next months, winter trench duty with its shelling and raids became almost unendurable and only improved a bit when the mud froze hard. The wet and the cold made life wretched. Respiratory diseases, “trench foot” – caused by prolonged standing in water – rheumatism and frost-bite were common. Many survivors would later say that this was the worst period of the war and that their spirits were never lower. Large-scale fighting did not resume until early 1917 when spring approached and a German offensive re-took areas previously heavily fought for.

Charles remained with the sixth field company, second division throughout. By the middle of 1917, they were in action in the mud at Passchendaelle. Charles’ brother Arthur was there too, with a different division. Eight weeks of heavy fighting took a huge toll on Australian troops.

At the end of 1917, he had a three week leave in England, returning to his unit in December, just in time for the German Spring Offensive, aimed at retaking Ypres in Flanders. The second division were involved in Messiness until March and then the battle of Lys in April. In June they participated in the very successful Battle of Hamel.

The Allies finally began to push the Germans back. Charles was involved in the Battle of Amiens and other attacks from the village of Villers-Bretonneux.

Then, on July 23rd, after weeks of very heavy fighting, Charles was affected by a mustard gas shell.

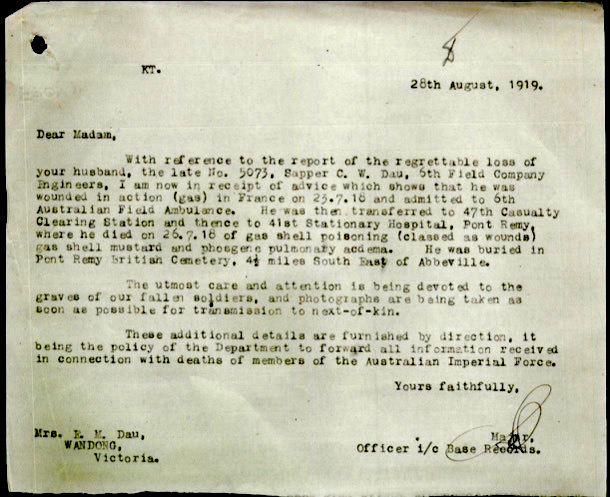

A letter to his wife, Edith, written in August the following year explains the story from here:

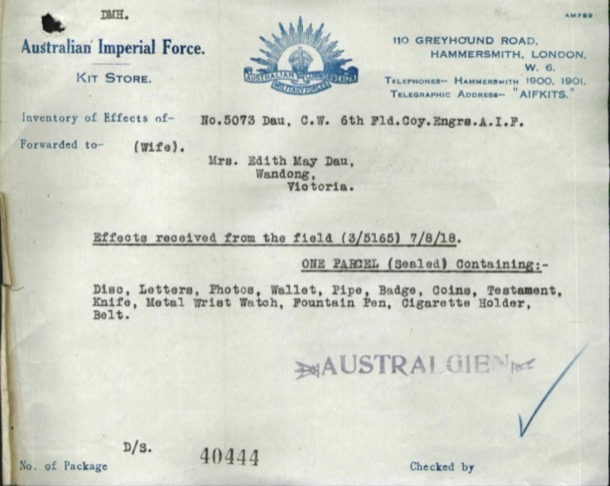

Edith received a parcel containing Charles' last few possessions:

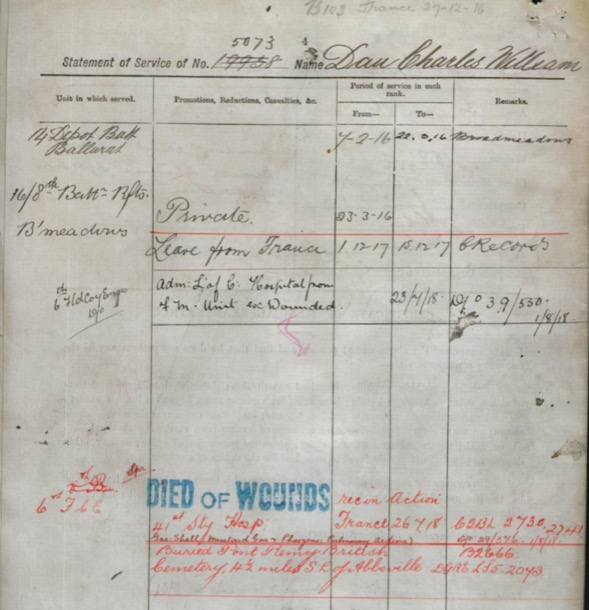

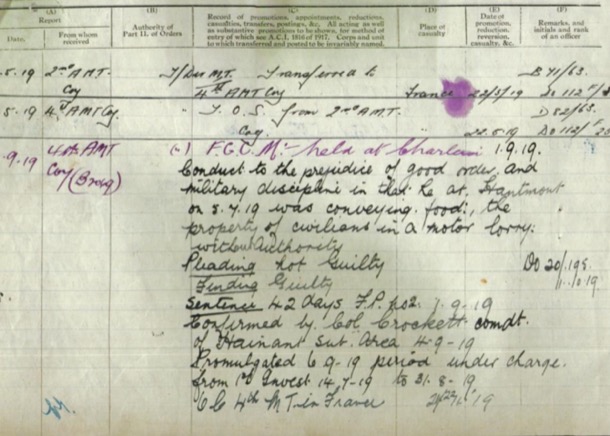

From Charles' military record:

Mustard Gas

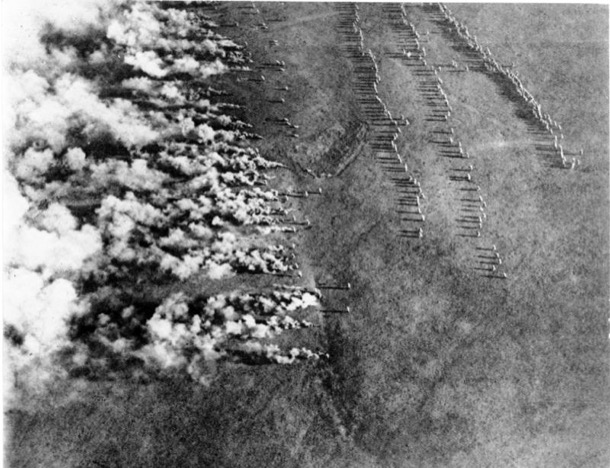

Chemical weapons were first used in World War I. They were primarily used to demoralize, injure, and kill soldiers in trenches, against whom the indiscriminate and generally very slow-moving or static nature of gas clouds would be most effective.

Some gases used actually killed soldiers, but mustard gas was more a disabling chemical. On initial exposure, victims didn’t notice much except for an oily or “mustard” smell, and so the first men exposed to this “mustard gas” did not even don their gasmasks. Only after a few hours did exposed skin began to blister, as the vocal cords became raw and the lungs filled with liquid.

Even if they did have their masks on, they developed terrible blisters all over the body as the gas soaked into their woollen uniforms. Contaminated uniforms had to be stripped off as fast as possible and washed - not exactly easy for men under attack on the front line.

Affected soldiers died or were rendered medically unfit for months, and often succumbed years or decades later to lung disease.

As the war went on both sides used various protective masks, and gas became less effective as an actual weapon, though its psychological power was enormous and both sides continued to use it . By 1918, one-third of all shells being used in World War I were filled with poison gas.

One nurse, wrote in her autobiography, "I wish those people who talk about going on with this war whatever it costs could see the soldiers suffering from mustard gas poisoning. Great mustard-coloured blisters, blind eyes, all sticky and stuck together, always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke."

PRIVATE W.A.E. DAU (DOW)

Walter Albert Edward Dau the third youngest and according to Marge and Alice ‘the black sheep of the family’ enlisted in the AIF in November !916. Wally’s medical record describes him as having fair hair and blue eyes. He was twenty-seven, unmarried and a motor driver by occupation. He sailed for England in March 1917 with reinforcements for the 21st Infantry Battalion and he returned to Australia in October 1922, where he was discharged from the Army in December of that year. On the tapes Marge and Alice recall that he was apparently a bit bookish and lived ‘as a bit of a hermit in Noogee.’ He died in 1974 maybe in Queensland.

Wally arrived in England and was initially based at Rollerstone a huge Army camp on the Salisbury plain. New arrivals were sent here and the placed in other training camps nearby. Between stints in hospital, Wally was assigned to the 6th Signals Battalion and then after a final few months at Grantham Military Hospital was trained as a machine gunner. Wally spent almost sixteen months moving between training facilities and several military hospitals.

The handwritten records mention Synovitis a painful, chronic inflammation of the joints, a ganglion on his arm and ‘Hysteria NYD’ [Not Yet Diagnosed]. While Wally was undergoing one of his hospital stays, his brother Charles was gassed and died in France. Finally in October 1918 Wally was transferred to the Machine Gun Corps, 21st Battalion and he was on track to go to France. Fate intervened and Wally sailed to France on the 28th of November, seventeen days after the war ended.

It is difficult to know why Wally was so long in England, but one month after Armistice, Wally was in France with the AIF Graves Unit. The Commonwealth Graves Commission had already been established in response to the public's reaction to the enormous losses in the war. Their work in France was to ensure that the final resting places of the dead would not be lost forever.

From the very first battles in the early weeks of the fighting on The Western Front, the number of military dead was already in the tens of thousands. Graves and burial grounds situated in the area of a battlefront were often damaged by subsequent fighting across the same location, resulting in the loss of the original marked graves.

Some bodies simply could not be retrieved from underground.

Added to this, the technical developments in the weaponry used by all sides frequently caused such dreadful injuries that it was not possible to identify or even find a complete body for burial.These factors were generally responsible for the high number of “missing” casualties on all sides and for the many thousands of graves for which the identity is described as “Unknown”. The AIF War Graves Unit was responsible for the cataloguing of the dead and the construction of the monuments and cemeteries.

One wonders what Wally's reaction was to this overwhelming task.

Wally, however found distractions. He had a daughter!

Amongst his military records is a translation of a letter written in 1933. The letter is from Madame Thomasson of Avignon France.

‘Please inform me where to write to Walter Dau, Australian subject’ involved in “War Grave Construction work in Belgium, who sailed from England to Australia in 1922. I should be very much obliged if you would supply me with information as to the whereabouts of this person who is the father of my daughter, ……. in order to define her position and nationality.’

The letter may never have reached Wally as it was passed between the Defence Department and Australia House, London with no record of delivery or response.

Another distraction for young Wally was 42 days of incarceration after he was Court-martialled for: ‘Conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline in that he ……was carrying food, the property of civilians a motor lorry, without authority’

Wally pleaded Not Guilty but the charge was upheld.

An interesting young man, many unanswered questions and a very different story to that of his two brothers who were in France during the fighting.

Heather Farm, Kilmore Junction ,1879

Three of the Dau children.

Fifty Years Ago at Kilmore Junction HEATHER FARM

In a lonely spot on the hillside, where the old cypress still lives and bends in the breeze, stands what is left of our once loved home, so loved in those old days gone by when a dear father and mother still lived to help us unravel life's tangled skein.

There the musk tree, mother planted, and cared for and loved—just beside the straggling remains of the lovely lilac trees; there the remains of the old gum tree where father sharpened his axe in its groove, and we children watched and wondered what difference it made; the path where the strawberries grew large and juicy on each side; the vines and the currants and gooseberry bushes—what tales they could tell could they speak. Father's pear tree, once laden with its golden store, now old and scrubby, still fading away.

The dairy house still stands, but the hum of the separator is silent. The stable, where Polly and Lofty enjoyed their hard-earned rest and feed, the cow yards: oh, what memories of Blossom, Violet and Peggy do those few remaining stone paths recall.

There is the old slip-panel, where father stood to welcome the children with smiling face when home on holiday: dear, gentle Dad, from whose lips we heard no unkind word; the wild cherry tree, where the boys carved their names, still there, the same beloved handwriting, although one sleeps in France and the other in Africa—duty nobly done.

The corner where the raspberries grew, juicy and red, at Xmas time; our favourite apple tree. How we loved to run down and see how many our thoughtful mother had saved for us, her wanderers. Memories!

Sometimes we wander back again to where the old home stood, and as we stand and think of other happy days gone for ever and gaze on all this, we seem to hear their loved voices again speaking to us, their children, although some of us are on the shady side of 60.

What would we give to live some of those old times gone by, and a kind word from father and a smile from mother? Seventeen of us—their children—were reared up to manhood and womanhood on the site of that once beloved home. The silent bush: no picture shows, no evening entertainments, just our books and our church on Sunday.

Oh, to live it all again. To once more call dear old Blossom, Peggy, and Strawberry home for milking. To feed again those poddy calves. To turn the old separator. To hear the voice again of our dear old teacher—who taught 13 of our family before he went to rest. To walk to the old church on Sundays and then home, where mother had laid the snow cloth with all things good for tea (and home made), and then go to the back paddock for wattle gum, where the pink and white heath grew, and wattle blossom bloomed.

Dear old home, we shall never see again. Only in our memory there will live that lovely past, which for us all, too soon, has fled and left only memories of other days. Some of us would love to live again at dear old Heather Farm.

Sarah Coles (née Dau)

McEwan Road, Heidelberg. 7/2/1929

The Poor Little Thing

Marge and Alice, with great drama, tell the story of our great, great grandmother whose name they do not know, and her subsequent marriage to Grandfather Dow, with whom she had eighteen children.

They had little factual information and their story is obviously based on stories told to them by their father. “That’s how the tale goes and the imagination boggles,” says Alice at one stage and indeed it did!

THE FAMILY TALE would have us believe that the our great, great grandmother, name unknown, met her prospective husband, first name unknown, at the Victoria Market. She was apparently a child of fifteen dragged off by a middle aged man to a poor farm miles out in the country of early colonial Victoria. The long and arduous journey into the night finished at Wandong where the poor little thing, ‘rolled up her sleeves and started milking cows straight away.’ She bore eighteen children and did much of the work, as her husband, a German immigrant from Bavaria, who was rumoured to have noble blood, sat behind the milking shed reading poetry. The poor little thing lived to 83 and grew very broad in the beam. Her husband as the tale goes died at 102 sitting up in bed singing a hymn.

The mind does indeed boggle. Was she a poor little thing? How much is ‘tale’?

You be the judge.

We also have a story extrapolated from FACTS provided by the Victorian Records Office, Ancestry Dot Com, Google, newspapers, shipping records and documents from England.

The ‘poor little thing’ was Martha Rye born in 1850 in Geelong in the Colony of New South Wales. The year after her birth in 1851 the Colony of Victoria was founded and separation from New South Wales was formalised.

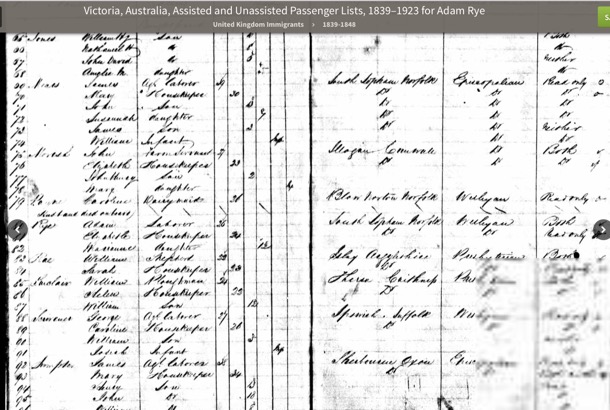

Martha Rye was the first child born in Australia to Adam (1822 - 1924) and Elizabeth (1824 - 1901) Rye, recently arrived immigrants to the young colony.

Adam and Elizabeth emigrated to Australia from South Lopham in Norfolk, England in 1848. They had with them one child, Marianne who was a year old. Adam was twenty-six and Elizabeth twenty-four.

Here is the South Lopham church in which they were married:

We know from the shipping records that they sailed on the sailing ship The Berkshire, arriving in Geelong on October the third, 1848. Their occupations were listed as labourer and housekeeper. He could read and write, she could read but not write.

We know that he had indeed worked as a labourer on his father’s farm, but he had also had a stint as a footman in the household of Lord Randall, which is where he tasted a bit of Queen Victoria’s wedding cake, shared with the staff by Lord Randall, who had been a wedding guest.

When he and Elizabeth left for Australia, they sat down to a farewell dinner with thirty-two of Adam’s brother and sisters (from three different mothers).

Adam lived 102 years, and when he was in his nineties, his colourful life story was written up by an enthusiastic journalist for a local paper. Note his editorialising in the following extract about “treacherous blacks”.

The family settled near Geelong, where they rented a piece of land to farm.

“While here Rye went off one day to the store for provisions, and after getting his supplies started for home, but darkness overtook him and he lost the track. He wandered about for some hours, and at last came upon a party of about 50 blacks. He thought it was no use trying to run away so he had to stand his ground. The blacks took his supply of bread, cheese, tobacco and a bottle of rum away from him and divided them amongst themselves, never leaving him a bite. Towards morning he made them understand where he lived and they directed him to his home, but having found out where he lived they paid him a couple of visits at night time and carried off his potatoes - not any that came to hand but the biggest and best and potatoes were worth £30 a ton in those days. The blacks at this time were very treacherous. They would watch the mothers going away for water and would steal into the huts and carry away anything they fancied even occasionally stealing a baby, which was never seen again, the blacks having roasted it for the camp's dinner. After a time he left for Melbourne. While here he met the same tribe of blacks, who recognised him, although the years had passed in the interim.”

Martha, our great great grandmother, born in 1850, was the first of eleven of Adam and Elizabeth’s children to be born in Australia.

The family moved to Broadmeadows, where Adam worked as a farm hand, cutting thistles and maintaining fences, as well as farming a piece of land himself. The newspaper article mentions wheat, potatoes and onions.

Here is an extract about the Broadmeadows farm.

He had about 2 acres of and with a splendid crop of onions on it. He and his family had been working hard getting these ready for market and left them in heaps about the ground ready to bag next day. To their utter astonishment, on going to finish their work they found that somebody had done the work for them, and had carted the lot away. There were from 10 to15 tons altogether, and this at £8 a ton was no small item to lose. However, he made up a bit on his crop of potatoes, which, although a light one, brought in £30 a ton. Butter was then 3 shillings a pound, bread 1 shilling a loaf, and a bag of flour as high as £5 a bag. This was owing in a good measure to the high rate of cartage.

This was the height of the gold rush, and Adam was not exempt from gold fever. In this story the “Black Forest” is mentioned. We found that it was an area near Mt Macedon, and part of a common route to the gold fields.

He had only one experience at mining and that when the Bendigo rush broke out. He with about a party of 20 shouldered their swags and tramped to Bendigo. In crossing through the Black Forest, as it was then called, they met with Black Douglas—a famous bushranger of he time. The party had just camped for the night when Douglas and men—numbering six—came on them. The party were all armed with guns and warned the rangers not to come any closer or they would fire. The robbers only had revolvers so thought it best to do as they were told. They, however, tried a couple of times during the night, but the miners were always ready for them and at last Douglas came to the conclusion it was no use trying again. The bushrangers would have had a fair haul if they had succeeded as each man was carrying a tidy sum of money at the time. Rye didn't do any good there although as he says it was a poor man's diggings all right, as gold was found on many occasions only a few feet from the surface. Everyone who could possibly follow the rushes went, and labourers of all kinds were very hard to get. In some instances if you went to an hotel for a meal you would be told that you'd have to cook it yourself if you wanted it, the cook having caught the gold fever and gone off. Farmers were in sore straits for men at harvest time and wages went up in a very short time from 10s to £4 a week. Finding the diggings no good to him Rye made his way to Colac, where farm labourers were badly wanted, and earned as much as £1 a day trussing hay.

We have ascertained that this move to Colac happened abut 1873, long after Martha had married Joachim Dau. Adam worked for a time as a farm hand and also a road builder.

At the time of this article, Adam was in his nineties. Elizabeth had died many years earlier. At that time he was living in Benalla with another of his daughters.

The old man dearly loves a game of euchre, and takes a very keen and intelligent interest in the game. In the summer months it was not uncommon sight to see him sitting out under the trees reading his Bible and prayer-book.

He died on his 102 birthday. Interestingly Alice and Marge tell the story of his death, but they remembered it as being about Joachim, Adam’s son in law and our great great grandfather. Joachim died in his eighties.

Alice says “and he died on his one hundred and second birthday, sitting up in bed and singing a hymn.” That definitely fits the facts and the personality of Adam Rye.

He is buried in the Benalla cemetery.

Adam and Elizabeth (both seated) with family members:

These early pioneers were the parents of the “unknown” girl in the market, “dragged away” to the farm in Wandong by the older German man. Marge and Alice knew nothing of their colourful lives.

Nor did they know anything about their great grandfather. “there was “some evidence of a high class family, ….. the Von Dows of Bavaria.”

In fact Johann Joachim Ties Dau was born in 1832 in Bukowko, (Neu Buckow in German) in present day Poland. His parents were Gottlieb and Anna. Their town, which they would have called Bukówko, was part of Pomerania, in present day Poland. Situated in what is known as the “Polish Corridor”, over the centuries Bukowko has also been part of Sweden, The Holy Roman Empire, Denmark, Prussia,, France (Napoleon) and East Germany.

Johann arrived in Australia during the 1850s with his wife, Maria (born Maria Winter), who was from the same town and six years younger. The couple acquired a farm at Wandong, near Kilmore.

In 1861 a child, Eliza, Louisa Dau was born. Maria died in childbirth. The baby lasted only a year before it too died.

So in 1865, the thirty-three year old Johann had suffered his wife’s death four years earlier, and his baby daughter, three years ealier.

……….

Now you have the facts and the family tale. We have the knowledge that our roots go back to the very early days of the Colony of Victoria and that the lives of these early settlers were touched by many of the events we read about in history books, including the Gold Rush, bushrangers and encounters with ‘the blacks’.

The immigrants, Martha's parents and husband came from England and Poland as young people looking for a new life.

Martha herself, an older child in a family of twelve children would have helped her mother both with daily tasks and the younger children. She was also according to the tale helping her father sell the produce from their small plot: not an easy life for a fifteen year old girl but probably not uncommon.

Was the older man (actually in his prime at only 33) at the market a good proposition? Was it the Victoria Market or one of the many local markets in the colony? After all Broadmeadows was the country then. Johann had lost his wife and child soon after they arrived in the colony and he owned a farm at Wandong, probably bigger than her father’s small rented plot in Broadmeadows. Did she take a chance, strike out on her own and opt for a better life?

We will never know but she and Johann produced 18 children many of whom also went on to lead colourful lives.

Poor little thing ????