Hair

This post therefore is about hairstyles, but we have allowed ourselves a much broader scope.

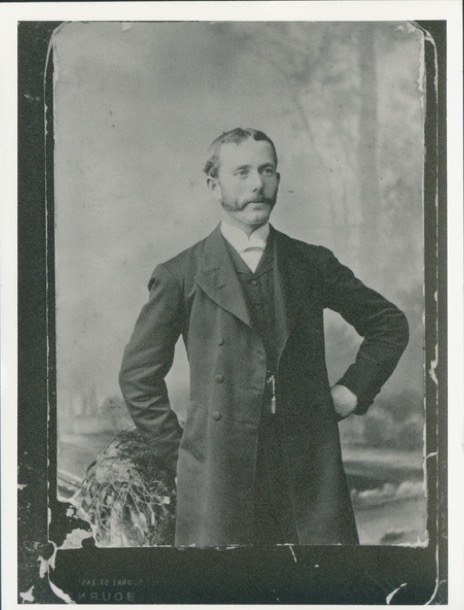

ALFRED JOHN COATES

Alfred John Coates, born in 1857, was probably in his late twenties when this photo was taken. He was our maternal great grandfather and was a Methodist Pastor for most of his working life. In this photograph Alfred is a young man in prime of life, dressed in formal dress and sporting the fashion of the day: mutton chop whiskers, carefully manicured to join artfully with the moustache. A man of destiny, the misty ‘bush’ behind him, he stands erect, eyes on the future. At this time Alfred was apparently a boiler maker in Ballarat.

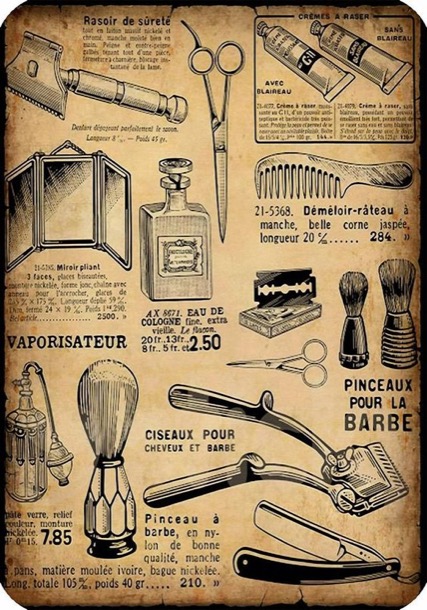

Men’s facial hair trends were changing rapidly in the late 1800s. Long beards were out and clean chins and cheeks and a well-manicured moustache were in. To achieve this look men would need to go to a barber two to three times a week or shave themselves.

Shaving oneself may have been a financial necessity at times but it could also be a dangerous procedure. Shaving was done with a straight steel razor that required care and expertise, not only in the act of shaving the gentleman, but also in the care of the blade. To keep it sharp, the blade was rubbed against a leather or canvas strap before each new shave. As well as the blade, shaving soap, shaving brushes, combs, oils and wax were essential items to achieve the desired effect.

Having a photograph taken in a studio was a special occasion and a relatively expensive exercise. One can imagine that Alfred may have had a trip to the barber to ensure that he looked his best.

Safety steel razor blades that made shaving much easier were not invented until 1895 by an American business man with French heritage.

King C. Gillette invented a low cost blade that was easily replaceable and gave men safety and the freedom to achieve the look desired themselves.

EMMA ELIZABETH DAU

Alfred married Emma Elizabeth Dau in 1888. He was thirty-two and she was twenty Maybe this photo was taken at this time:

Emma is dressed in the style of the day, hourglass figure no doubt with a corseted waist as she gazes into her future with a determined tilt of her chin. Her hair is tightly curled at the front and pulled back into either a bun or pinned up plait.

Unlike the men who had barbers to attend to their needs, there don’t appear to be many ladies' hairdressers. Women had many home implements and potions and maybe sisters and mothers helped each other with their hair.

Young Emma’s tight curls may have been created with curling irons. A curling iron consisted of a metal rod that was held over a flame or burning alcohol to heat it, before wrapping the hair around it. Hey presto, curls!

Later in life, Emma wore her hair in a more relaxed style, loosely pulled back from her face and pinned up into a bun at the back:

When this photo was taken, the height of fashion for women was to wear their hair with more volume at the sides. This was created by using clumps of hair leftover in combs and brushes, to pad out the sides. Emma would not have gone to these lengths in later life, but on her dressing table she would have had a brush, comb, hand mirror and china box, with a lid for the collection of hair caught in brushes or combs. We can remember our grandmother, Alfreda, also having these items on her dressing table. She wore her hair long all her life. During the day it was loosely tied back in a bun, brushed out at night, and the ‘ratts’ collected from the brush and placed in the china box. She then plaited her hair into a loose, single long plait and was ready for bed.

NINE DAU SISTERS

Emma Coates, was born Emma Dau. She was one of seventeen. The first nine of these were girls.

We have three amazing little photos of some of the Dau children. We have spent a long time staring at these images, noticing little details, wondering about the lives of these nine little girls.

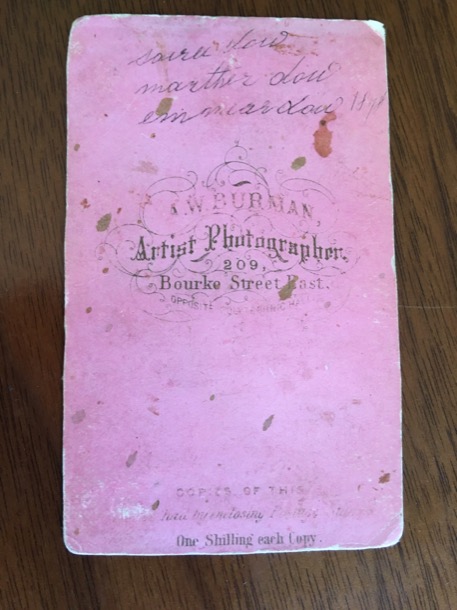

The first question we had was, "Were the three photos taken at the same time?". There is such a family resemblance, we weren’t sure at first whether they were different people in the three photos. The carpet gives away that they were taken in the same studio. On the back of one of the playing card sized photos, we see “one shilling per copy”. For context, at that time, a shilling was more than a day’s wage for a working man.

It seems most likely that the three photos were taken on the same day, and they are the nine oldest children, all daughters, of Joachim and Martha Dau, our great, great grandparents.

The photo of the three eldest has writing on the back:

The fact that Martha is misspelt as “marther”, and that no capital letters are used, might be a clue. It was not our mother Alice, nor her parents. None of them would have made such a basic spelling error! The surname is listed as “Dow”.

If those names are correct, then these are the three eldest Dau children. Standing is Sarah, the eldest. the other two are Martha, known as Mishi, and Emma, our great grandmother.

Thanks to the Wandong Historical group, we have the details of nearly all the Dau children.

The next three girls are Bella, Jane and Sophia, followed by Alice, and two others, possibly Annie and Nance, although some sources have Annie and Nance as the same person.

There is no date on these photos, but there are nine girls. The nine first Dau children, all girls were born between 1866 and about 1878. This puts the date of the photos at about 1880, with Sarah, the eldest, aged 14 and the youngest aged 2.

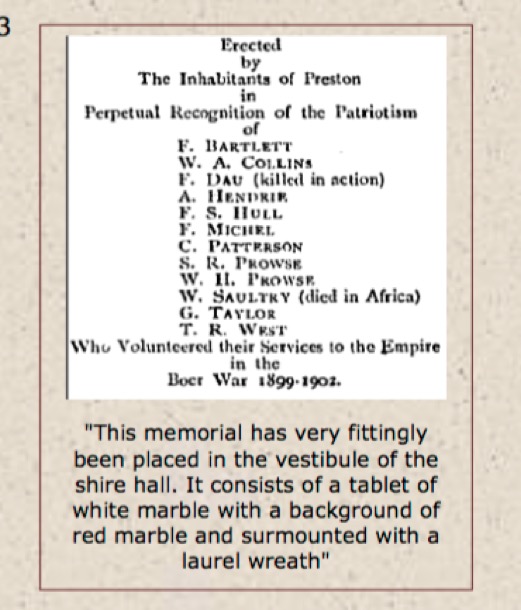

The girls’ father, Joachim, had spelt his surname, Dau. We don’t know the exact date they changed it to Dow, but Frederick enlisted to fight in the Boer War as Dow in 1901, and Arthur, who became a professional soldier, changed his name by deed poll to Dow. The same anti German sentiment that caused the British Royals to change their surname to Windsor from Saax Coburg was no doubt responsible. And yet the Dau spelling persists alongside the Dow spelling, right up until 1929, when Sarah, the eldest wrote about her childhood. Our mother and aunt did not even know about the Dau spelling.

The photographer is listed on the back as Burman, 209 Bourke St Melbourne. The building is still there. This is what it looks like today:

There are a number of old photos by Burman available on line, with that tell-tale carpet visible in some. This one, “Portrait of a Lady”, which uses the same chair as two of our photos, is from C1865.

We picture the little farm girls, in their new dresses, in the big noisy city. They would have come on the train, to Flinders Street from Wallan, and walked the three city blocks to the studio.

The city streets would have looked like this:

Their hair would had been in rags overnight. The curls in Sarah, Martha and Emma’s hair have been successful; the others less so. All of them have a ribbon holding their hair back from their face.

The dresses are interesting. The same fabric and pattern seems to have been used for the three eldest girls. Who made them? The next three also have a similar style. All have sturdy boots and frilly pantaloons. These outfits would have been worn to church on Sundays. Did they wear them for the train journey, or change at the studio?

The only other girl, born in 1887, preceded and followed by the seven boys, was Ethel. She wrote diary entries, still held by the Wandong Historical group. Ethel wrote about the boots, which are such a feature of these little girls’ photos. “the rough track across the paddocks and hills, two miles to the little school at Wandong. In wintertime, we had to cross many flooded gullies. We wore strong boots and I was often peeved, as I compared my strong shoes with the dainty ones worn by the other girls at school.”

It was quite an expense to provide boots for so many children.

Our appetite for finding out more about this family is well and truly whetted. We plan further exploration, including an excursion to Wandong.

THREE HOLM SISTERS

These three young women, probably photographed just before the first world war are (left to right) Alfreda, Beatrice and Berta Holm. Alfreda, our maternal grandmother, was the oldest of the three, perhaps just twenty at the time. The three sisters have their long hair swept back in gentle waves, to a loose bun or twist at the back.

We wonder whether they did the white work on their shirts? We know that Beatrice and Berta spent time working in Finders Lane, doing the white embroidery known at the time as “white work”. So much we can only guess at.

They all gaze into the distance: Alfreda with a determined steely gaze, Beat with a quizzical half smile and Bert’s beautiful eyes not quite hiding her vulnerability. We can only guess, as they gaze into a future where world war is imminent.

Alfreda wore her hair long all her life. We can remember her brushing her hair at night and putting it into a long plait.

TWO COATES SISTERS

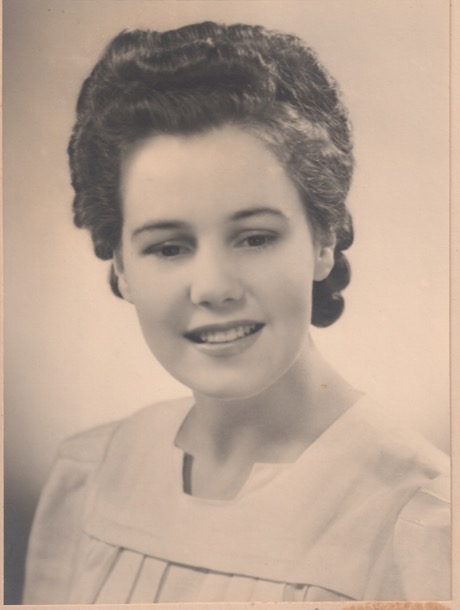

It’s hard to be a younger sister, but our mother Alice, was the fairly plain younger sister of an extraordinary beauty.

She didn’t have to deal with social media, but, when she was growing up in the 1930s, feminine beauty was important for girls.

Alice was an intelligent and able scholar, and, thank goodness, this was highly valued in her family. Her mother, Alfreda, had made sacrifices and fought for her own education. For their later secondary school, the girls were sent, at huge expense, to a city based secondary school, all the way from Croydon.

Only the wealthiest or most determined families sent their girls to school, after the age of fourteen. At McRobinson Girls’ High School, Marge and Alice were taught by, and shared classes with, the very brightest and best: future women scientists, lawyers and doctors, who would pave the way for our own generation.

But, from her school reports, we see that, while she held her own on the whole, Alice was not exceptional in that auspicious company. And she was crippled, probably her whole life, by a sense of inferiority.

And it is in their respective hair cuts from that time, that we see how the contrast between the two girls was accentuated.

When I stare at those grainy old photos, at Marge’s lush locks, and Alice’s blunt, unfashionable short bob, and straight fringe, I cannot help but ask “Why?”. Why did Alfreda allow her younger daughter to wear such an unflattering style. Why was the difference in feminine beauty accentuated and underlined so prominently by the two hairstyles? How might Alice’s life have been different, had she been encouraged to make the most of her looks, as well as her brains?

Even as they began working life, both at Maribyrnong Munitions Factory, in 1939, the difference remained. Here Marge is on the far right, and Alice on the far left. Alice is nineteen and Marge twenty-one. But the choice of hairstyle reflects very different attitudes about their appearance:

THE VICTORY ROLL

These two studio photographs of Marge are portraits of a beautiful young woman, but what does the hair tell us?

Here, a younger Marge still has very long hair, worn up now, as befitted a young woman who was no longer a child. Pretty curls and barrel curls were the look, and Marge had beautiful, wavy, very cooperative hair and was able to construct ‘the look’ very successfully.

An older Marge, maybe just twenty, posed for this studio photograph as a young woman of the war years, in the “hottest” style of the time. This photograph shows a confident young woman with a job, and presumably many admirers.

During the war, particularly during the Battle of Britain, the ‘Victory Roll’ evolved as a very popular and flattering hairstyle. The style was based on an aerobatic manoeuvre performed by pilots to signify victory. The planes would spin horizontally in celebration. The ‘Victory Roll’ hairstyle would have been difficult to execute, so hours of practice and experimentation was required. The style has stood the test of time, as it is still popular today in ‘retro’ dressing. There are many YouTube videos available with full and detailed instructions.

‘THE SET ‘

After the second world war, women’s hair fashion was dominated by ‘the set’, often a weekly set. Some women did their own at home, but others, such as our mother Alice, went to their local hairdresser.

The set involved a headful of rollers, tightly wound on wet hair, then dried under a hood dryer. This often took almost an hour, so there was time to read or chat.

Through the ages, and the generations of our family, both sexes’ hair styles have been influenced by the fashion of the day. We have all had cuts, or not. We have curled and permed and coloured and bleached, with varied results.

Today, people are not rigidly restricted to one style, as they were in the past, but have any options.

The lyrics from the musical Hair says it all: .

‘Gimme a head with hair

Long beautiful hair

Shining, gleaming,

Streaming, flaxen, waxen’

War Service

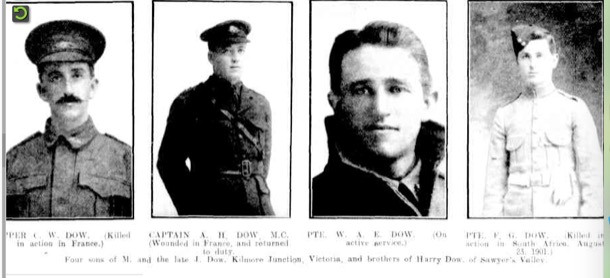

Our family stories research has led to the discovery of four great great uncles: four brothers who were soldiers. They were four of the seventeen children of Martha and Joachim of Heather Farm in Wandong, about whom we wrote in "The Poor Little Thing" on June 8th, 2016 and "Heather Farm" on August 3rd, 2016. Our maternal grandfather Alf, was their nephew.

Learning their stories, imagining their experiences, fitting their details into the wider sweeps of military history has been enthralling and rewarding.

We present the four Dau (Dow) brothers, Frederick, Arthur, Charles and Walter.

Frederick and Arthur actually enlisted as Dow, an anglicised version of Dau. It is a constant confusion.

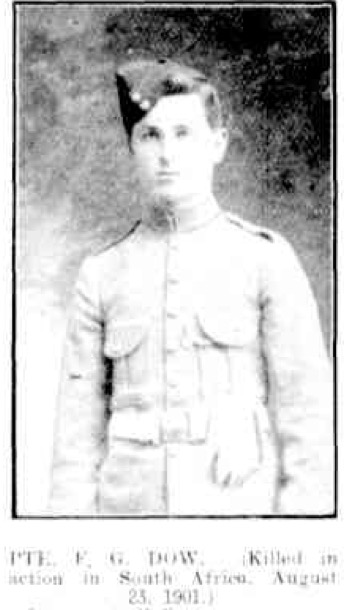

PRIVATE F. G. DOW

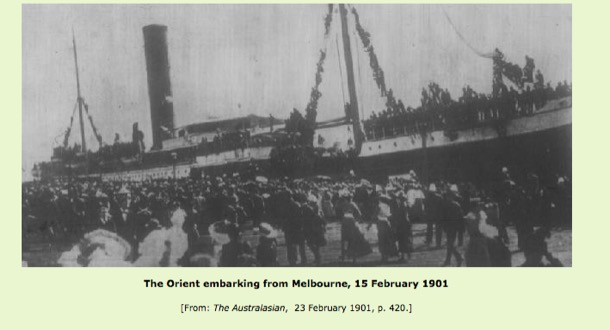

Australia was twenty-eight days old when nineteen year old Frederick sailed on The Orient out of Melbourne, bound for South Africa and the Boer War. His company was the Fifth Victorian Mounted Rifles.

Britain had colonised the southern part of South Africa eighty years earlier and had had an uneasy relationship with the other colonisers of this area, the Dutch Boers, who had been there for a hundred and fifty years longer. Tensions had escalated to war in 1899, and the British Empire was required to send troops to participate.

By 1901, the war had become a drawn out guerrilla affair mostly in the desert-like Transvaal area with small groups of Boer soldiers attacking and then disappearing back into the harsh dry landscape.

Many of the “colonial” troops, like Frederick were bushmen, tough, self reliant and skilled at shooting from horseback: exactly the set of skills needed for this type of warfare. But it was very hard on men and horses alike. Most of the fighting took the form of small skirmishes, but sometimes the men had to attack remote farmhouses, confiscate the livestock, destroy the farms and escort the women and children to the notorious concentration camps where thousands died. R G Keys of South Moorabbin wrote of making captures of large numbers of prisoners and cattle and having brought in large numbers of Boer families. “We have also burnt thousands of acres of grass and a number of farms and have destroyed everything of any use to the Boers.”

They spent long periods in the saddle with few opportunities to bathe or change their clothes; lice were a constant problem. Temperatures on the veld ranged from relentless heat during the day to freezing cold at night.

Private F W Collins wrote, “What I can see of the war is that the Boers can keep it on as long as they like, the only way is to starve them out. They get right in the mountains, and there are bullets whizzing about you and you cannot see any enemy. We are going from daylight till dark, up at 4 o’clock in the morning, and it is sometimes midnight before we get in again, so you can imagine we feel quite knocked out. When I get back to old Victoria I’ll do nothing but sleep.”

We don’t have much detail about Frederick’s death, but Lord Kitchener, Field Marshall in charge of the war, reported in one of his dispatches: "on the 23rd August Lieutenant Colonel Pulteney had a sharp engagement with the enemy on the west side of the Schurveberg, in which the Victorian MR (Mounted Rifles) had 2 men killed and 5 wounded.” One of those two men killed was Frederick Dow.

Two years later, his mother, Martha, and brother Harry inserted this memorial in the local paper:

In loving memory of dear Fred, who was killed in battle near Vryheld, South Africa, August 23, 1901; aged 19 years and 6 months.

Tis two sad years ago today,

The trial was hard, the shock severe,

To part with one we loved so dear.

He is gone, but not forgotten,

Never shall his memory fade;

Sweetest thought shall ever linger

Round about our soldier’s grave.

MAJOR A. H. DOW

Arthur was on one of the first ships to leave Melbourne for the war. He sailed from Station Pier Melbourne on the Orvieto on October 21st 1914. There were huge crowds to wave off this first wave of volunteers.

Soldiers from the Orvieto disembarking at Egypt:

Arthur was a career soldier. He had joined up as a military engineer, aged seventeen in 1908 and had already been promoted to Warrant Officer.

Like all of those first soldiers, after a short time in Egypt, Arthur was dispatched as part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force to what would become known as Anzac Cove, Gallipoli. He was there for the very first Anzac Day landing, but went ashore “several days” later. He must have watched from his ship as the first few waves of shore boats struggled amid Turkish bullets and shells that rained down from the cliffs. By the time it was his turn, things were still very chaotic and dangerous. It took ten days for the troops to be safely dug in.

On June 16th, he was Injured and was treated at the hospital on the Greek island of Lemnos.

He went back to Gallipoli ten days later.

At the beginning of August, Arthur was detached for duty to Assistant Adjutant General 3rd Echelon in Alexandria (which dealt wth military discipline, though he was in the “records section&rdquo![]() .

.

By March 1916 he was with the Fourth division engineers at the huge Anzac training area near Cairo, called Tel-el-Kebir, a six mile long “tent city”, where he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant.

He must have participated in the notorious three day march across the desert in searing heat to Serapeum, on the Suez Canal.

Here there was more training, in preparation for the move to France, and he was promoted again to Lieutenant. On June 2nd, he travelled on the ship “Kinsfaun Castle” to Marseilles, in the south of France.

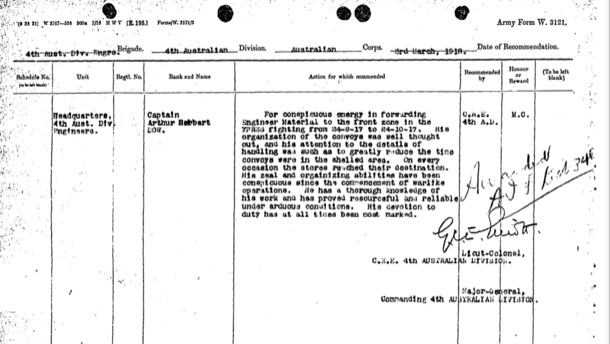

The next mention in Arthur’s record is six months later, in January 1917, where he is “mentioned in despatches” (a sort of honour) and then again on June 26th, where he is promoted to Captain.

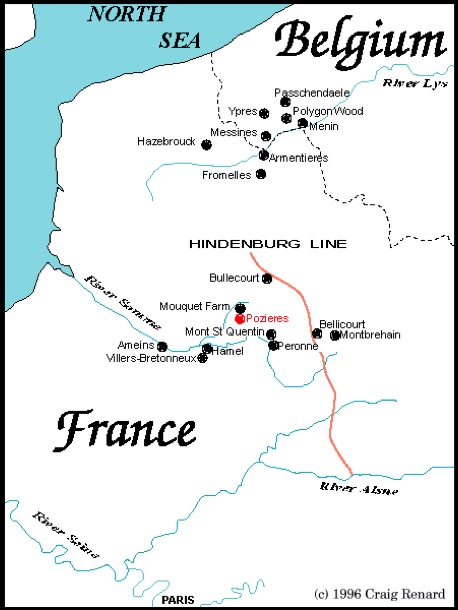

We know what he was involved in during those couple of years in France and Belgium because we know what unit he was in.

He fought at Ypres and Messines Ridge and Passchendael: all infamous places in the history of the first world war.

It was for his work from 24th September through to 24th October that he was awarded the Military Cross.

Arthur was a military engineer. Engineers, also known as sappers, were essential to the running of the war. Without them, other branches of the Allied Forces would have found it difficult to cross the muddy and shell-ravaged ground of the Western Front. Their responsibilities included constructing the lines of defence, temporary bridges, tunnels and trenches, observation posts, roads, railways, communication lines, buildings of all kinds, showers and bathing facilities, and other material and mechanical solutions to the problems associated with fighting.

At the time Arthur won the Military Cross, the 4th Division was involved in the battle of Polygon Wood and then the third battle of Ypres, Passchendaele. It is from the Ypres-Passchendaele area that we get the iconic images we have of trench warfare in a landscape of deep mud and water filled shell holes with broken off toothpick trees, stretching away into a hazy distance; where falling off the duck board paths meant drowning in mud. By the time Passchendael was captured in November 1917, the Australians had fought for eight weeks and suffered over 38 thousand casualties.

At the beginning of December Arthur had a fortnight’s leave in Nice, Italy and on his return he was sent to England to Brightlingsea to train engineers. It must have been a welcome break, but he was back in France by May, 1918.

He was wounded in action on August 8th. At that time his company, the 14th Field Company Engineers was laying wire barriers across the area to be advanced upon in front of the village of Villers Brettoneux. They were harassed by constant German shellfire, and snipers.

The resulting battle was called the Battle for Amiens, and was a resounding success, although between August 7th and 14th, the Australians lost six and a half thousand men.

Arthur left for Australia on September 27th, and within six weeks the war was over.

He remained in the services for a few years. In 1920 he had a few months’ successful treatment for “depression and irritability”. On his application form, where he had to provide supporting evidence for his entitlement to this help, he wrote a single word: “Anzac”.

By 1940, one year into the second world war, Arthur, who had been working in a Government desk job in the civil service, rejoined the army as a Major. He was 49, married with two children, and living in St Kilda.

His war this time, was fought at a desk, sometimes in the Middle East and sometimes back in Australia. His war record mentions positions like “Hiring and Claims”, “Accomodation and Quartering”. He left finally in October 1945, aged 54. During this time he had treatment for an affected patch of skin in his mouth. The doctor mentions that this is the spot where Arthur’s pipe customarily sits.

The last mention of Arthur in the war record is application for repatriation consideration for a minor health issue. He was a healthy 72 and living in Boronia.

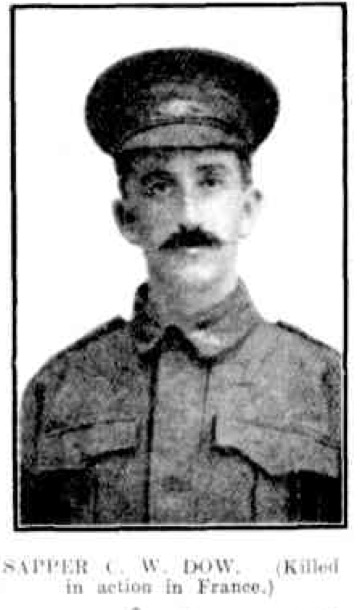

SAPPER C.W. DAU (DOW)

Like his brother Arthur, Charles enlisted as a sapper, or military engineer. He joined up in February 1916 in Hamilton, where he had been working as a railway “ganger”. He was thirty, slim, fair haired and blue eyed and was married to Edith, who was still back in Wandong with their three children.

He left for Europe in April and by October had joined the Second Division in Belgium, before marching to the Somme area in France. His division was involved in attacks on a collection of German trenches known as The Maze,

The main Somme fighting came to an end on 18 November in the rain, mud, and slush of the oncoming winter.

Over the next months, winter trench duty with its shelling and raids became almost unendurable and only improved a bit when the mud froze hard. The wet and the cold made life wretched. Respiratory diseases, “trench foot” – caused by prolonged standing in water – rheumatism and frost-bite were common. Many survivors would later say that this was the worst period of the war and that their spirits were never lower. Large-scale fighting did not resume until early 1917 when spring approached and a German offensive re-took areas previously heavily fought for.

Charles remained with the sixth field company, second division throughout. By the middle of 1917, they were in action in the mud at Passchendaelle. Charles’ brother Arthur was there too, with a different division. Eight weeks of heavy fighting took a huge toll on Australian troops.

At the end of 1917, he had a three week leave in England, returning to his unit in December, just in time for the German Spring Offensive, aimed at retaking Ypres in Flanders. The second division were involved in Messiness until March and then the battle of Lys in April. In June they participated in the very successful Battle of Hamel.

The Allies finally began to push the Germans back. Charles was involved in the Battle of Amiens and other attacks from the village of Villers-Bretonneux.

Then, on July 23rd, after weeks of very heavy fighting, Charles was affected by a mustard gas shell.

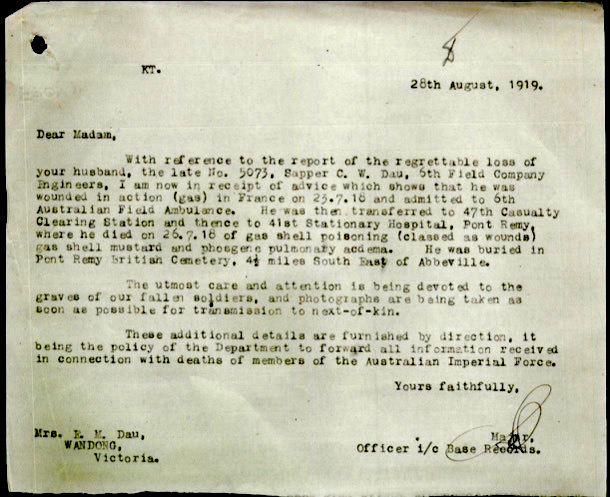

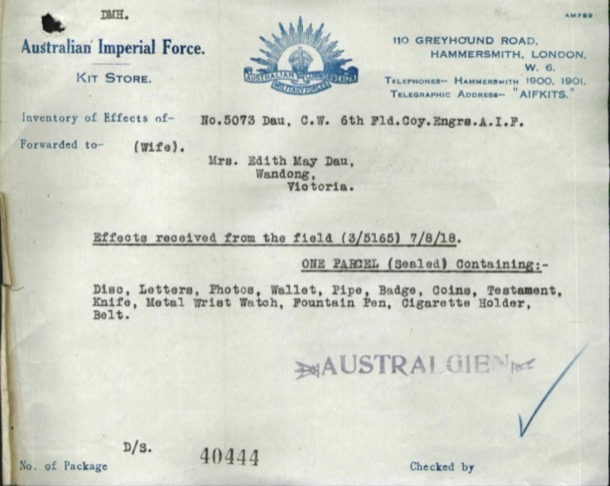

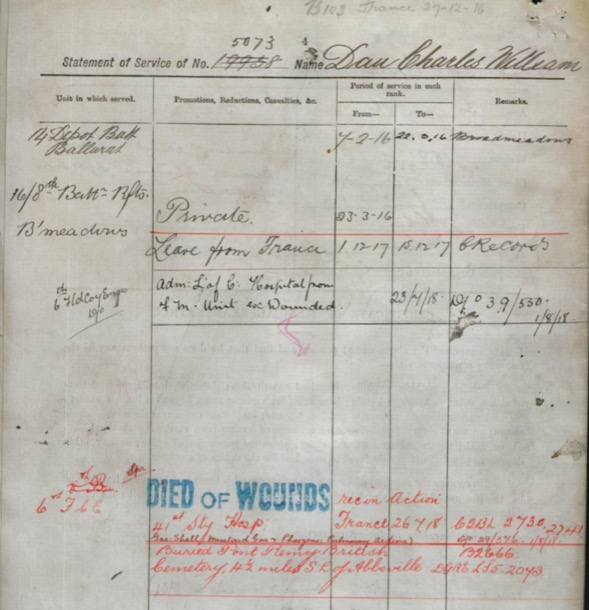

A letter to his wife, Edith, written in August the following year explains the story from here:

Edith received a parcel containing Charles' last few possessions:

From Charles' military record:

Mustard Gas

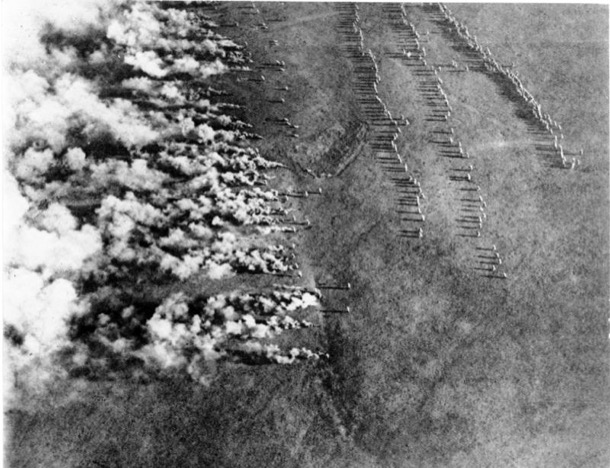

Chemical weapons were first used in World War I. They were primarily used to demoralize, injure, and kill soldiers in trenches, against whom the indiscriminate and generally very slow-moving or static nature of gas clouds would be most effective.

Some gases used actually killed soldiers, but mustard gas was more a disabling chemical. On initial exposure, victims didn’t notice much except for an oily or “mustard” smell, and so the first men exposed to this “mustard gas” did not even don their gasmasks. Only after a few hours did exposed skin began to blister, as the vocal cords became raw and the lungs filled with liquid.

Even if they did have their masks on, they developed terrible blisters all over the body as the gas soaked into their woollen uniforms. Contaminated uniforms had to be stripped off as fast as possible and washed - not exactly easy for men under attack on the front line.

Affected soldiers died or were rendered medically unfit for months, and often succumbed years or decades later to lung disease.

As the war went on both sides used various protective masks, and gas became less effective as an actual weapon, though its psychological power was enormous and both sides continued to use it . By 1918, one-third of all shells being used in World War I were filled with poison gas.

One nurse, wrote in her autobiography, "I wish those people who talk about going on with this war whatever it costs could see the soldiers suffering from mustard gas poisoning. Great mustard-coloured blisters, blind eyes, all sticky and stuck together, always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke."

PRIVATE W.A.E. DAU (DOW)

Walter Albert Edward Dau the third youngest and according to Marge and Alice ‘the black sheep of the family’ enlisted in the AIF in November !916. Wally’s medical record describes him as having fair hair and blue eyes. He was twenty-seven, unmarried and a motor driver by occupation. He sailed for England in March 1917 with reinforcements for the 21st Infantry Battalion and he returned to Australia in October 1922, where he was discharged from the Army in December of that year. On the tapes Marge and Alice recall that he was apparently a bit bookish and lived ‘as a bit of a hermit in Noogee.’ He died in 1974 maybe in Queensland.

Wally arrived in England and was initially based at Rollerstone a huge Army camp on the Salisbury plain. New arrivals were sent here and the placed in other training camps nearby. Between stints in hospital, Wally was assigned to the 6th Signals Battalion and then after a final few months at Grantham Military Hospital was trained as a machine gunner. Wally spent almost sixteen months moving between training facilities and several military hospitals.

The handwritten records mention Synovitis a painful, chronic inflammation of the joints, a ganglion on his arm and ‘Hysteria NYD’ [Not Yet Diagnosed]. While Wally was undergoing one of his hospital stays, his brother Charles was gassed and died in France. Finally in October 1918 Wally was transferred to the Machine Gun Corps, 21st Battalion and he was on track to go to France. Fate intervened and Wally sailed to France on the 28th of November, seventeen days after the war ended.

It is difficult to know why Wally was so long in England, but one month after Armistice, Wally was in France with the AIF Graves Unit. The Commonwealth Graves Commission had already been established in response to the public's reaction to the enormous losses in the war. Their work in France was to ensure that the final resting places of the dead would not be lost forever.

From the very first battles in the early weeks of the fighting on The Western Front, the number of military dead was already in the tens of thousands. Graves and burial grounds situated in the area of a battlefront were often damaged by subsequent fighting across the same location, resulting in the loss of the original marked graves.

Some bodies simply could not be retrieved from underground.

Added to this, the technical developments in the weaponry used by all sides frequently caused such dreadful injuries that it was not possible to identify or even find a complete body for burial.These factors were generally responsible for the high number of “missing” casualties on all sides and for the many thousands of graves for which the identity is described as “Unknown”. The AIF War Graves Unit was responsible for the cataloguing of the dead and the construction of the monuments and cemeteries.

One wonders what Wally's reaction was to this overwhelming task.

Wally, however found distractions. He had a daughter!

Amongst his military records is a translation of a letter written in 1933. The letter is from Madame Thomasson of Avignon France.

‘Please inform me where to write to Walter Dau, Australian subject’ involved in “War Grave Construction work in Belgium, who sailed from England to Australia in 1922. I should be very much obliged if you would supply me with information as to the whereabouts of this person who is the father of my daughter, ……. in order to define her position and nationality.’

The letter may never have reached Wally as it was passed between the Defence Department and Australia House, London with no record of delivery or response.

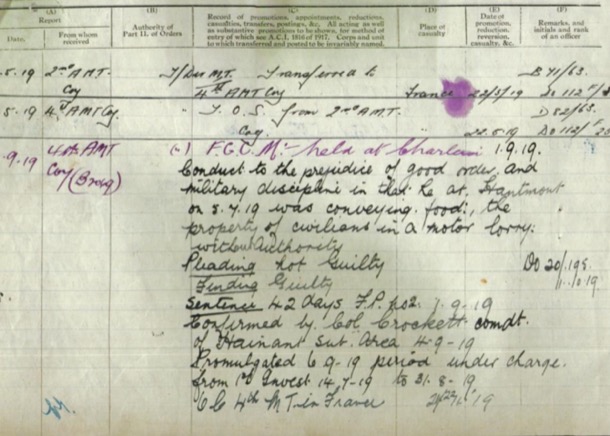

Another distraction for young Wally was 42 days of incarceration after he was Court-martialled for: ‘Conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline in that he ……was carrying food, the property of civilians a motor lorry, without authority’

Wally pleaded Not Guilty but the charge was upheld.

An interesting young man, many unanswered questions and a very different story to that of his two brothers who were in France during the fighting.

Heather Farm, Kilmore Junction ,1879

Three of the Dau children.

Fifty Years Ago at Kilmore Junction HEATHER FARM

In a lonely spot on the hillside, where the old cypress still lives and bends in the breeze, stands what is left of our once loved home, so loved in those old days gone by when a dear father and mother still lived to help us unravel life's tangled skein.

There the musk tree, mother planted, and cared for and loved—just beside the straggling remains of the lovely lilac trees; there the remains of the old gum tree where father sharpened his axe in its groove, and we children watched and wondered what difference it made; the path where the strawberries grew large and juicy on each side; the vines and the currants and gooseberry bushes—what tales they could tell could they speak. Father's pear tree, once laden with its golden store, now old and scrubby, still fading away.

The dairy house still stands, but the hum of the separator is silent. The stable, where Polly and Lofty enjoyed their hard-earned rest and feed, the cow yards: oh, what memories of Blossom, Violet and Peggy do those few remaining stone paths recall.

There is the old slip-panel, where father stood to welcome the children with smiling face when home on holiday: dear, gentle Dad, from whose lips we heard no unkind word; the wild cherry tree, where the boys carved their names, still there, the same beloved handwriting, although one sleeps in France and the other in Africa—duty nobly done.

The corner where the raspberries grew, juicy and red, at Xmas time; our favourite apple tree. How we loved to run down and see how many our thoughtful mother had saved for us, her wanderers. Memories!

Sometimes we wander back again to where the old home stood, and as we stand and think of other happy days gone for ever and gaze on all this, we seem to hear their loved voices again speaking to us, their children, although some of us are on the shady side of 60.

What would we give to live some of those old times gone by, and a kind word from father and a smile from mother? Seventeen of us—their children—were reared up to manhood and womanhood on the site of that once beloved home. The silent bush: no picture shows, no evening entertainments, just our books and our church on Sunday.

Oh, to live it all again. To once more call dear old Blossom, Peggy, and Strawberry home for milking. To feed again those poddy calves. To turn the old separator. To hear the voice again of our dear old teacher—who taught 13 of our family before he went to rest. To walk to the old church on Sundays and then home, where mother had laid the snow cloth with all things good for tea (and home made), and then go to the back paddock for wattle gum, where the pink and white heath grew, and wattle blossom bloomed.

Dear old home, we shall never see again. Only in our memory there will live that lovely past, which for us all, too soon, has fled and left only memories of other days. Some of us would love to live again at dear old Heather Farm.

Sarah Coles (née Dau)

McEwan Road, Heidelberg. 7/2/1929